The Staircase of the Self

When children copy us, we think it’s cute. When adults copy us, we threaten to sue.

This odd dynamic shines a light on our relationship with imitation, and the way it morphs over time. When we interact with a child, we operate under the assumption that the child is still learning about her place in the world, so we accept emulation as a prerequisite to her development. It’s not only normal to see the child copying the behavior of adults, it’s something that brings us immense joy to see.

Psychologist Alfred Adler believed that this imitative behavior is the result of an “inferiority complex” that is universal in childhood. Since all children enter a world inhabited by towering adults, the sheer physical differences between themselves and their parents causes this feeling of inferiority to develop. To alleviate this, the child will emulate the behavior of these lumbering giants, and will learn how to overcome various challenges by copying what they do.

Another way to look at this is that the sense of self is not strongly cultivated in a child. Most of the child’s connection to her individuality is purely based on sense data – it’s limited to the pang of hunger she feels, the physical warmth she experiences, the discomfort she wants you to resolve.

But her awareness of who she is as a unique person has been offloaded to the adults. My wife and I will look at our newborn daughter and say things like, “She seems quite introverted” or “She’s sensitive to people’s energy,” but my daughter (likely) isn’t making any of these character interpretations about herself.

This lack of a sense of self is a spiritual goal for many adults, but that’s only because we know how to take care of our basic biological needs. Young children, on the other hand, literally cannot survive without the presence of caretakers, so having no sense of self doesn’t do them any good. The survival of the self is reliant upon interactions with others, so the shaping of their identity depends on who is there to provide for them regularly.

Imitation is the birthplace of human behavior. There’s no way around this fact, and we all intuitively understand this to be true. However, why is it also intuitive for us to scorn imitation as we age? Why does it become desirable to discard societal norms to become our “authentic selves,” or to escape this sense of self entirely?

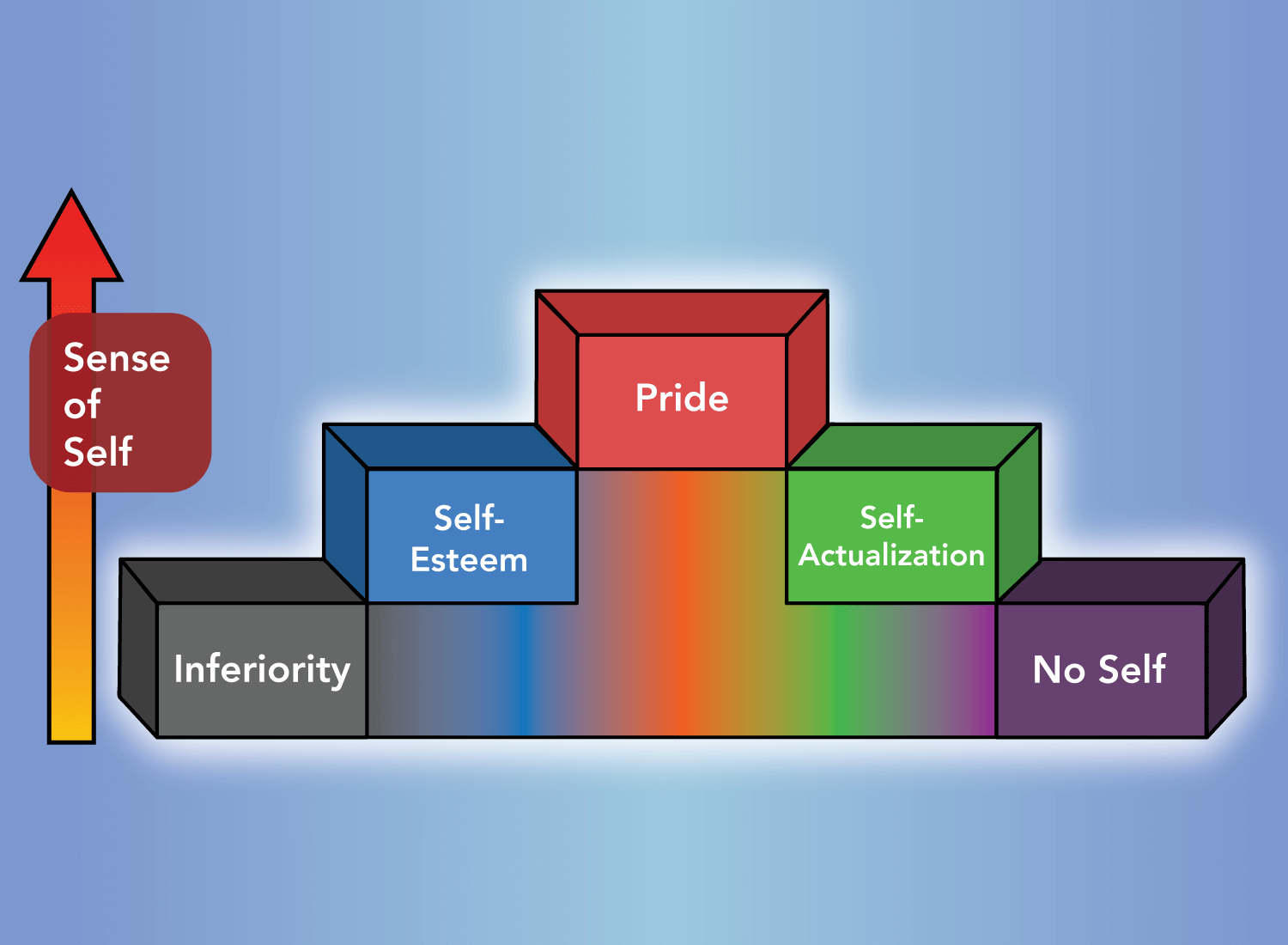

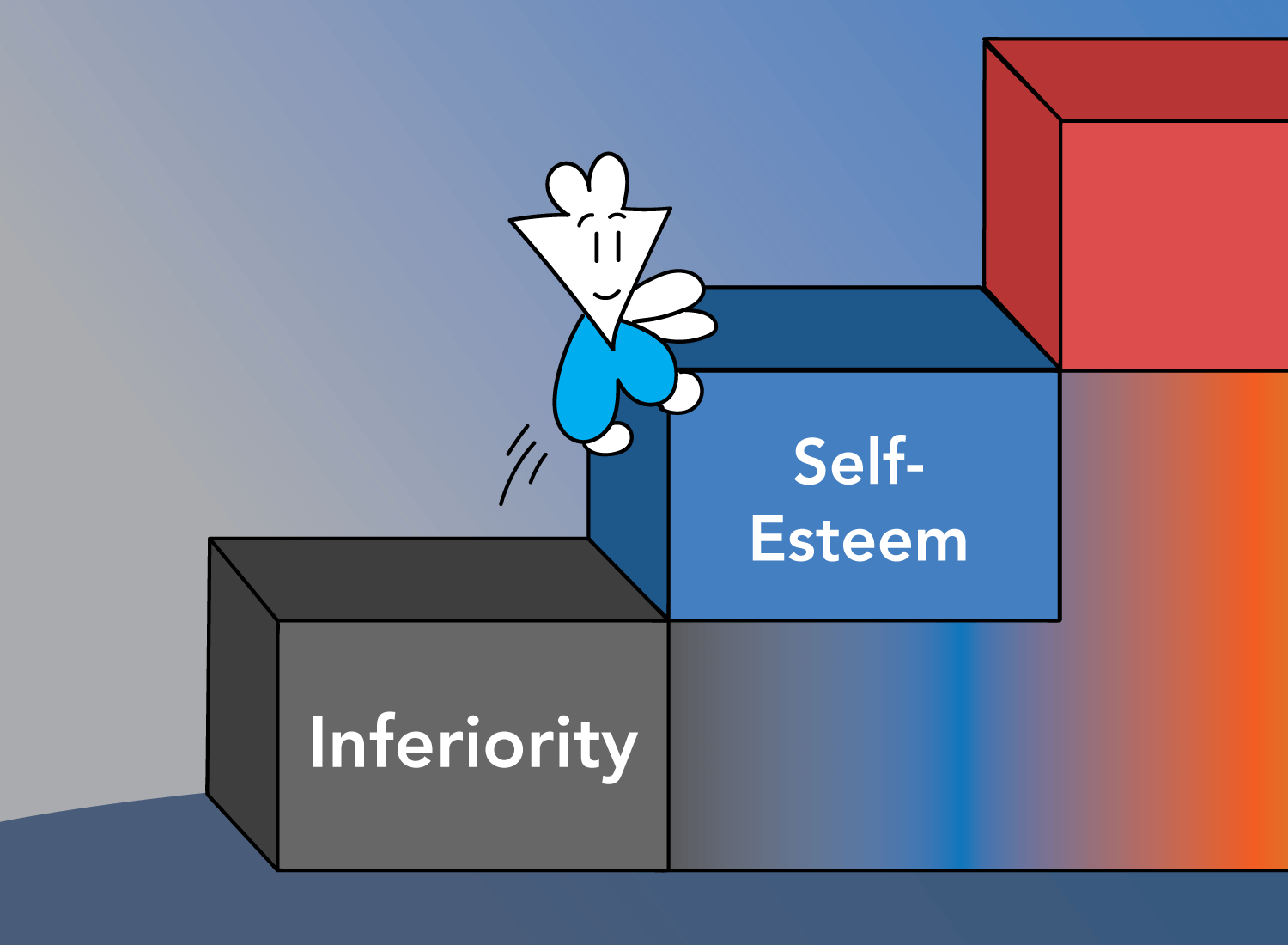

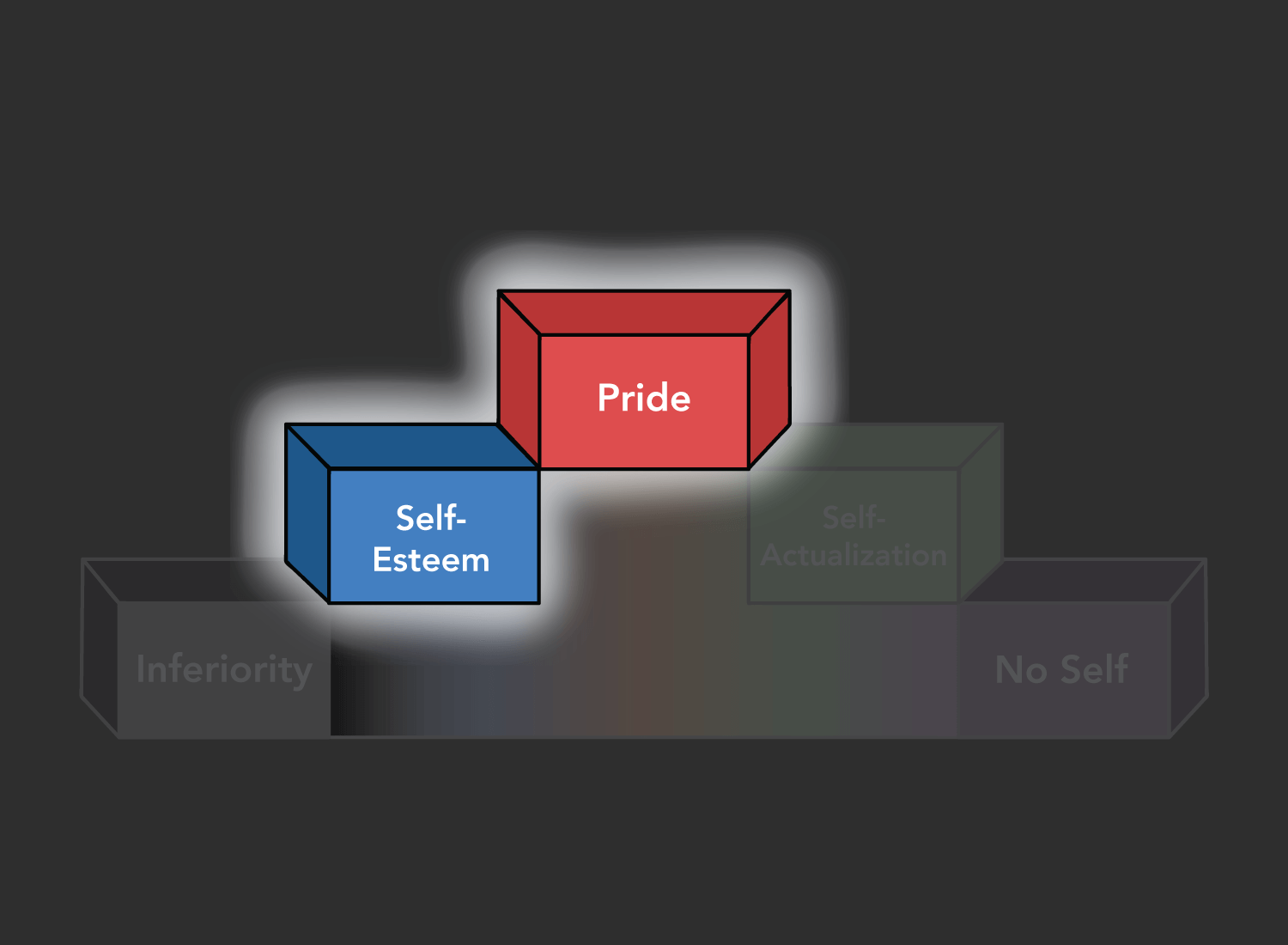

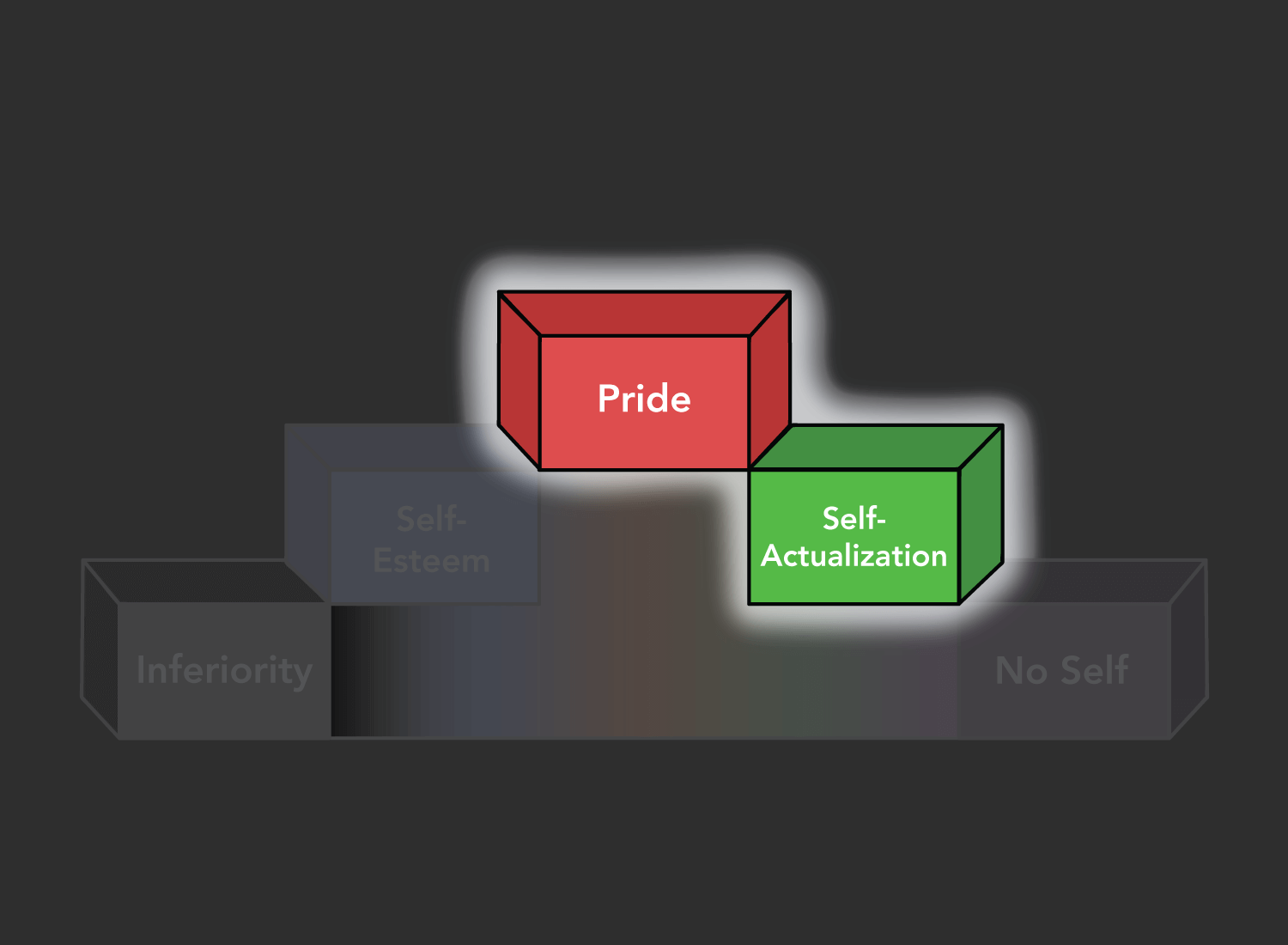

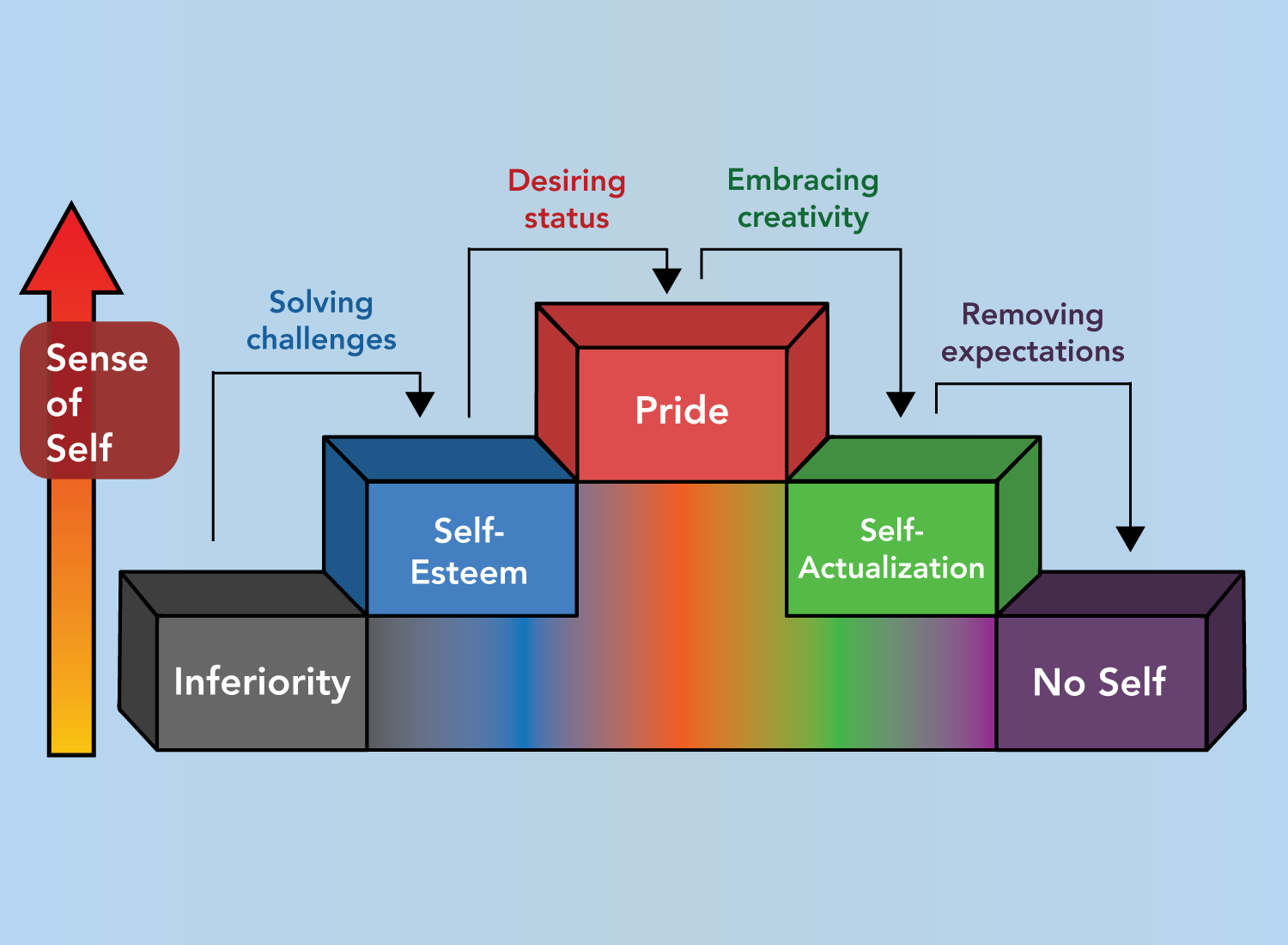

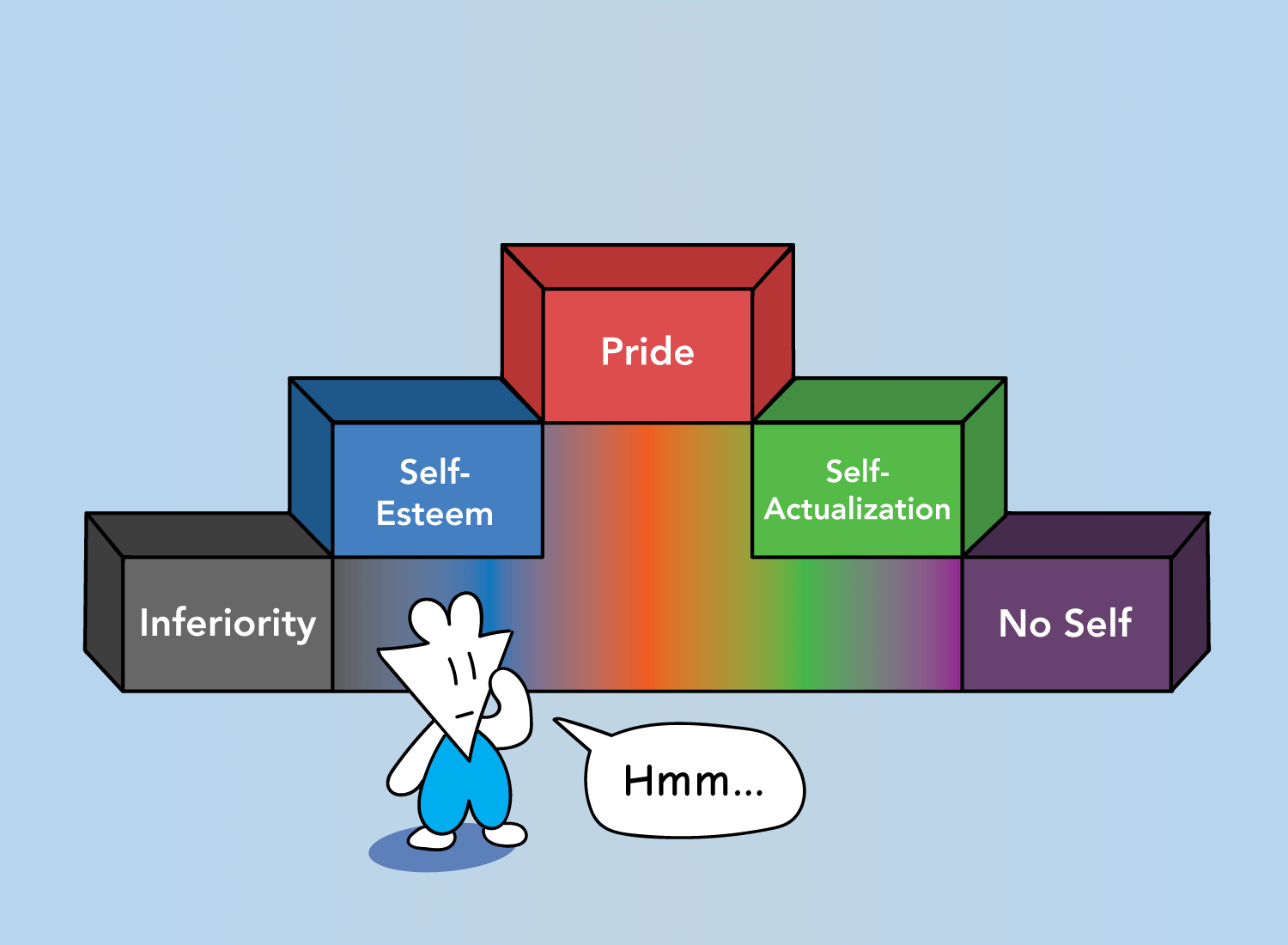

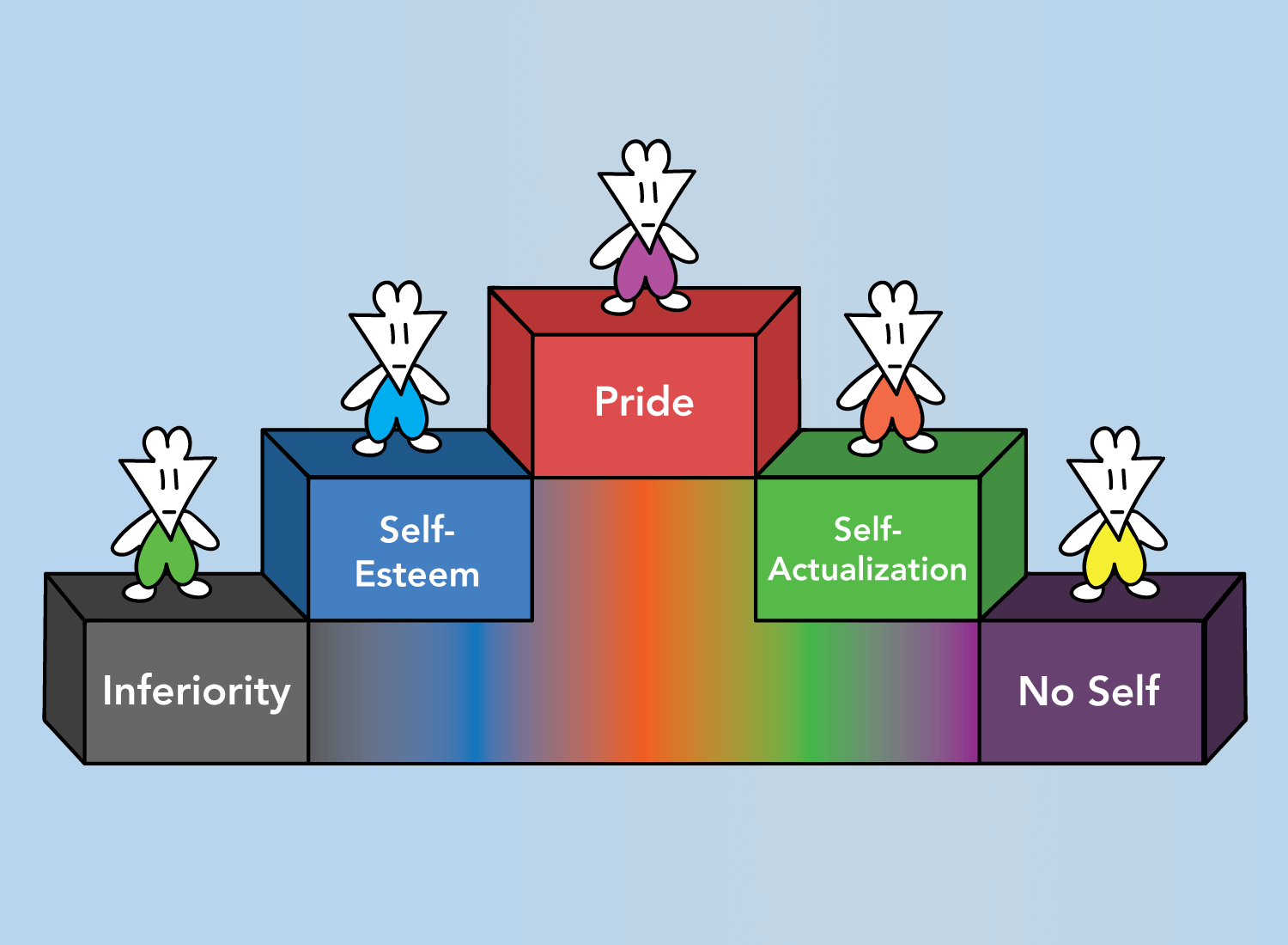

Well, to answer these questions, we’re going to have to take a journey through the stages of one’s identity, and how we internalize it at each level. To do this, I’d like to introduce what I call The Staircase of the Self:

As the diagram indicates, the position of each step is tied to how strongly one identifies with their sense of self, or the feeling of being a distinct individual navigating the world. One thing you’ll notice is that the diagram is symmetrical, so there are two steps occupying the same horizontal position at different points in the journey (e.g. Self-Esteem and Self-Actualization). This is because both these steps embody a similar association with identity, but do so with different lenses. We’re going to go into this in more detail later.

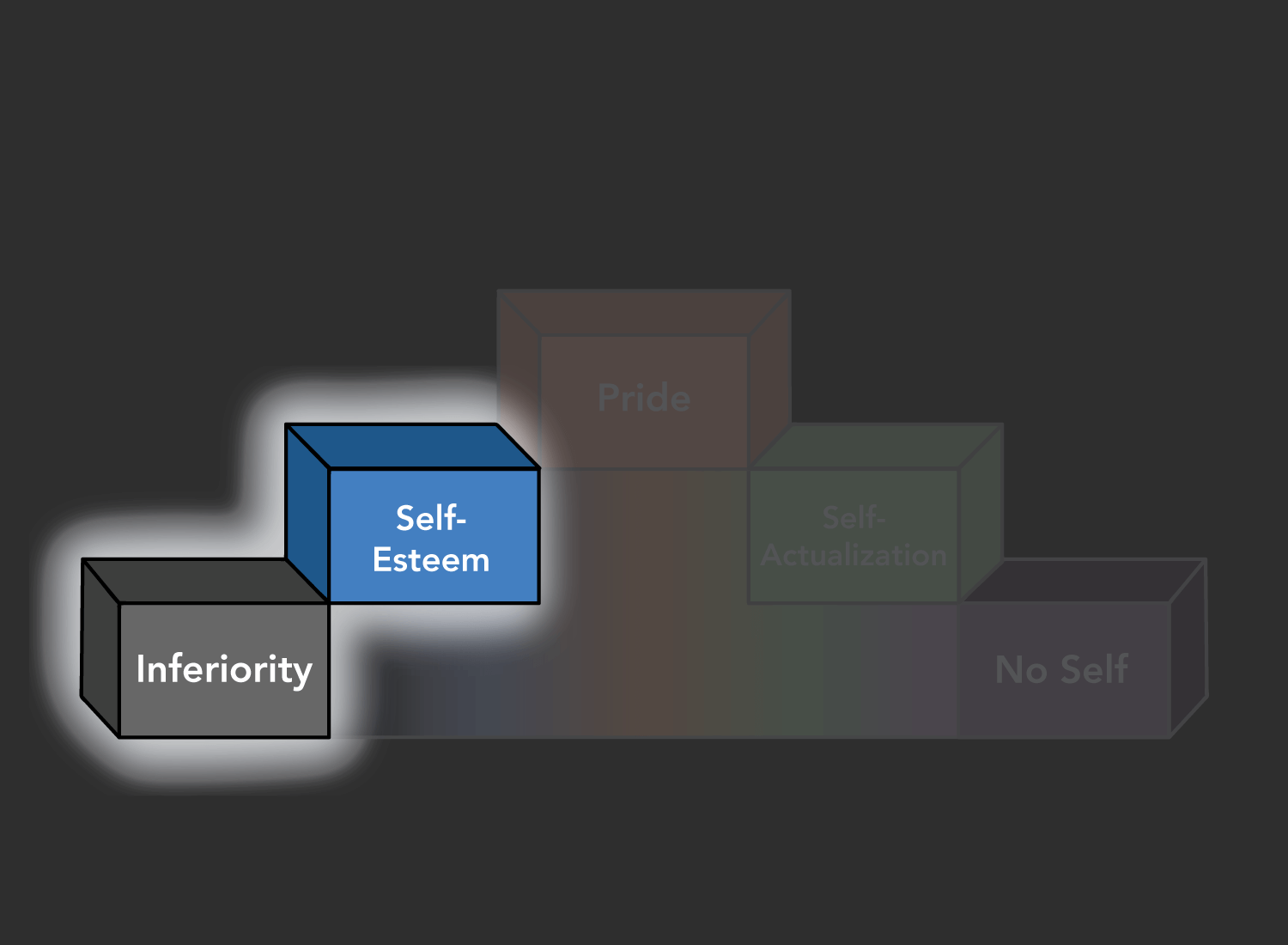

But for the time being, we’re going to focus on the first two steps, and see what it means to move out of utter dependency, and into a semblance of independence.

From Inferiority to Self-Esteem

The feeling of inferiority is largely due to an absence of a sense of self, but not in the way monks and meditators view it. This texture of “no self” originates from the helplessness we all experience as infants, and the complete reliance we must have on others to sustain our lives. Our behaviors are driven by fear, this fear lends itself to inferiority, and this inferiority causes us to outsource our identities to whoever we think has the answers.

So how do we identify the presence of our own unique intellect?

The feeling of inferiority is certainly not limited to infants, but by viewing this question through the lens of child psychology, we’ll arrive at a pretty good answer.

Jean Piaget, an influential 20th century psychologist, keenly observed that infants develop their intellect not through social interaction, but by personal action. Piaget initially thought that language was the primary developer of the intellect, but he noticed that an infant’s rapid capacity to interact with her physical surroundings is how she actually learned. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t “goo-goo gah-gah”ing with family members that developed her mind, but the way she used her senses to navigate the material world around her.

Piaget used this observation to propose that intellectual development happens in four distinct stages, each of which progresses from the more concrete (touching and arranging objects) to the more abstract (categorization to verbal reasoning). What makes progression possible is the child’s ability to build a “schema” (aka mental model) of the world, to introduce something foreign to that schema, and then to have the child update that schema to accommodate that foreign thing.

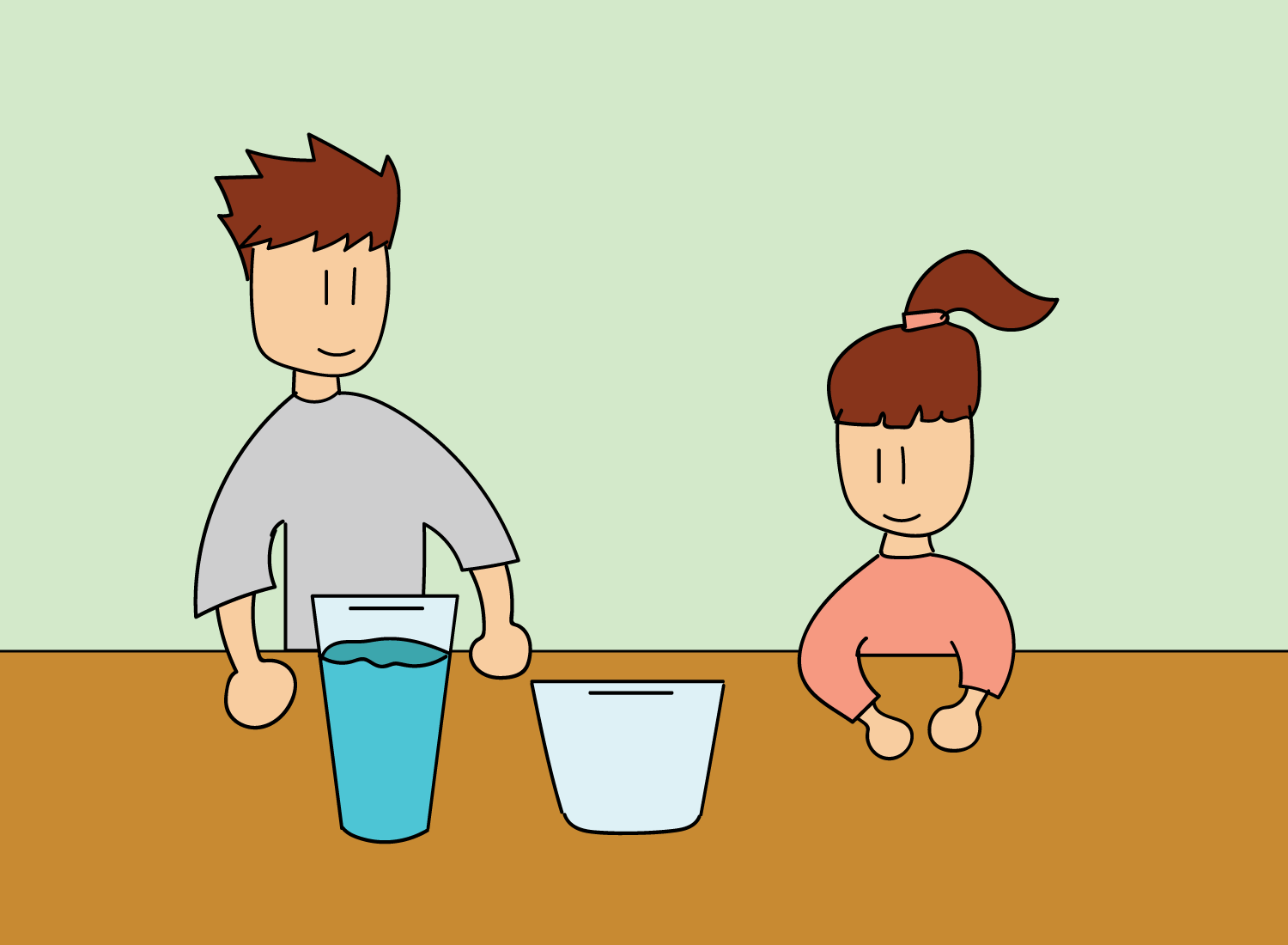

So for example, let’s say you show a child two glasses of different sizes. One is tall and thin (which holds water), while the other is short and wide (which is empty):

Then let’s take the contents of the tall glass and pour it into the short glass:

If this is the first time the child has seen this, she will believe that the shorter glass now holds less water than the taller one did. Since her existing schema takes differences in height to indicate changes in quantity, she will be unable to understand how both cups contain the same amount of water.

The only way for the child to accommodate this new knowledge is for her to take action and try it out herself. It doesn’t matter how much you sit her down and explain the mechanics, the only way for her to update her schema is to break the old one by integrating this foreign reality.

Intellectual development is deeply personal, and can only occur when one takes on the experiential challenges required to update their schemas. This is why Piaget called for classrooms where each child’s progress was individually accommodated by the teacher, and learning was more interactive. Agency plays a big role in how we cultivate our intellectual curiosity, as this type of willful action is what allows us to trust our own cognitive capabilities.

At its core, self-esteem is about having the confidence to solve problems on your own accord. And the way you do this is by regularly facing challenges that stretch the boundaries of your mind, which in turn shatter and update the preexisting models you had of the world. The more you do this, the more you cultivate your sense of judgment, which allows you to shut the door to inferiority.

This is easier said than done, largely because inferiority is the platform in which existence begins. It’s what you feel when you look to other people’s solutions to solve your personal problems, and this type of emulative behavior is what is required to progress through childhood. But with each challenge we face and resolve, we slowly transcend our reliance on others, and develop our unique lens to view the world through.

As you reach the step of self-esteem, the sense of self grows in turn. Confidence is a belief in how strongly your sense of agency is tied to favorable life outcomes, and the greater it is, the more you carve out a space for yourself in this world.

Self-esteem is invaluable in discovering who you are, but there comes a point where this independence begins to thirst for something greater.

And it is here where the utility of self-esteem begins to fall apart.

From Self-Esteem to Pride

All social disturbances and upheavals have their roots in a crisis of individual self-esteem, and the great endeavors in which the masses most readily unite [are] basically a search for pride.

– Bruce Lee

The paradox of self-esteem is that in order to have confidence in yourself, you need to better understand the social context in which you operate in. For example, if you want to be a great manager, you have to be acutely aware of all the dynamics you have with your team members. If you want to be a great entrepreneur, you have to figure out how to build an awesome solution that other people would find helpful.

This is inevitable because even though life is a single-player game, meaning is ultimately derived on multi-player mode. We can only navigate existence through our own lens, but it’s through the connections we make with other people that gives the journey its purpose.

Self-esteem is complicated for this very reason. So much of it is tied into how useful we are to others, and our confidence grows the more we are rewarded for our actions. This confidence boost leads to a higher attachment to the sense of self, which means that we look to further differentiate ourselves from everyone else.

And when it comes to differentiation, humanity has used one crude tool to achieve this since the dawn of our existence:

The desire for status.

Any quest for status begins with an attachment to some identity, and then using a strong sense of self to climb up that particular silo. Corporate ladders are a common example of this phenomenon. Academic hierarchies are another. Others are primarily concerned with influence, which can be seen in abundance on social media or any other metric-heavy medium.

The first thing status does is that it changes the nature of confidence. Confidence is no longer gauged by your internal benchmark of progress; it is contingent upon the praise you receive from others. This makes your sense of self fragile, as its condition hinges upon reactions that are not your own. The tide of other people’s opinions never follow any predictable pattern, so you begin to operate from an unstable foundation.

In order to compensate for this, we introduce the element of pride.

Pride is an overcorrection to our fragility in confidence. It’s a staunch attachment to an identity, regardless of what may or may not be true. It’s our way of saying “screw you” to anything that flies in the face of our deeply-held beliefs, no matter how sound those arguments may be.

Bruce Lee explained the difference between self-esteem and pride beautifully in his book, Artist of Life:

Pride is a sense of worth derived from something that is not part of us, while self-esteem derives from the potentialities and achievements of self. We are proud when we identify ourselves with an imaginary self, a leader, a holy cause, a collective body of possessions. There is fear and intolerance in pride; it is insensitive and uncompromising.

Pride likes to masquerade as confidence, but given enough time, it reveals its true face. Someone who says they’re proud to be a member of a political party is so attached to that identity that they will fear any legitimate opposition to it. Someone who is proud of their accomplishments will fear any attacks that are made to their body of work.

Like status, pride appears to embody a powerful sense of self, but in reality, it’s all an illusion. In the same way that joy and suffering are two sides of one coin, so too are pride and fear. To be proud of anything is to fear its loss, and this attachment is what makes this step such a fragile place to stand.

Despite that, we all know what it’s like to stand on this step. We know what it’s like to achieve something and to proudly attribute it to a quality of ours. We know what it’s like to be part of a group and to wear that identity for all to see. I know I have.

The thing about pride is that it tends to have practical benefits. Being proud of your abilities is a gravitating force, as it exudes an aura of confidence to others. It can attract influence and attention, as it draws in those with similar pursuits. It can make you a more desirable employee, which translates to a higher paycheck that drops into your account every two weeks.

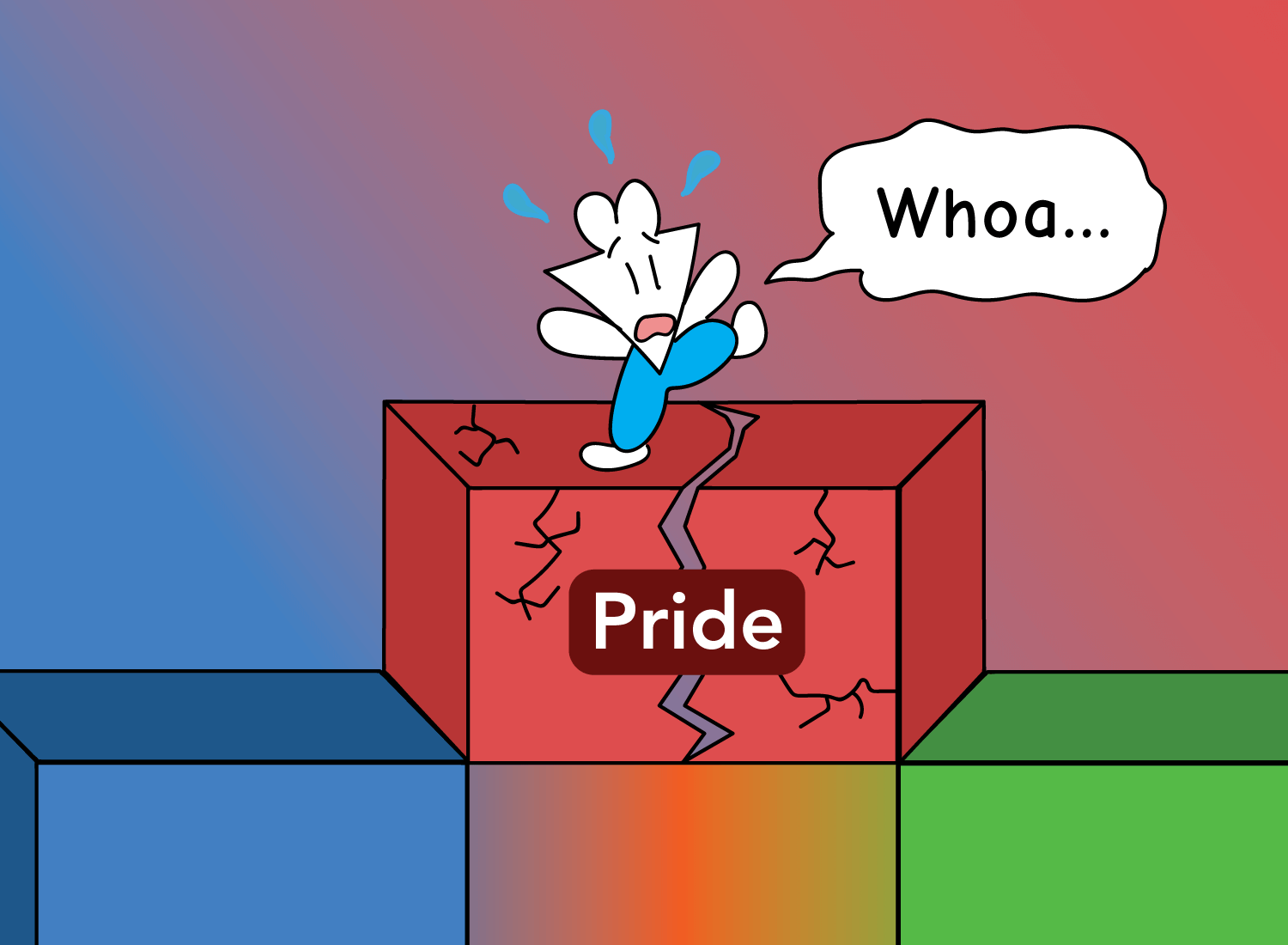

However, once your pride serves these base-level desires, its utility fades rapidly. This is because pride locks you into a caricature of yourself, and makes you feel like you have to present a version of yourself that you may have already outgrown.

Interestingly enough, we need to experience the heights of pride before making the transition away from it. Humanity learns best through elimination, and personal experience is its greatest teacher. We need to indulge in the pursuit of more before embracing the power of less. We have to desire status before realizing that it’s not the answer. Similarly, we need to have a strong sense of self before understanding that it’s all an illusion.

And this is where we begin our descent to the next step of the staircase.

From Pride to Self-Actualization

We started this journey with a reflection on imitation, and how all of us begin life by copying everyone else to survive. As things progress, we learn how to solve challenges on our accord, which results in self-esteem and a cultivation of the sense of self. Imitation is no longer fashionable, and we make it a point to grow our identities in a manner that differentiates us. The sense of self balloons as a result, and pride dominates the show.

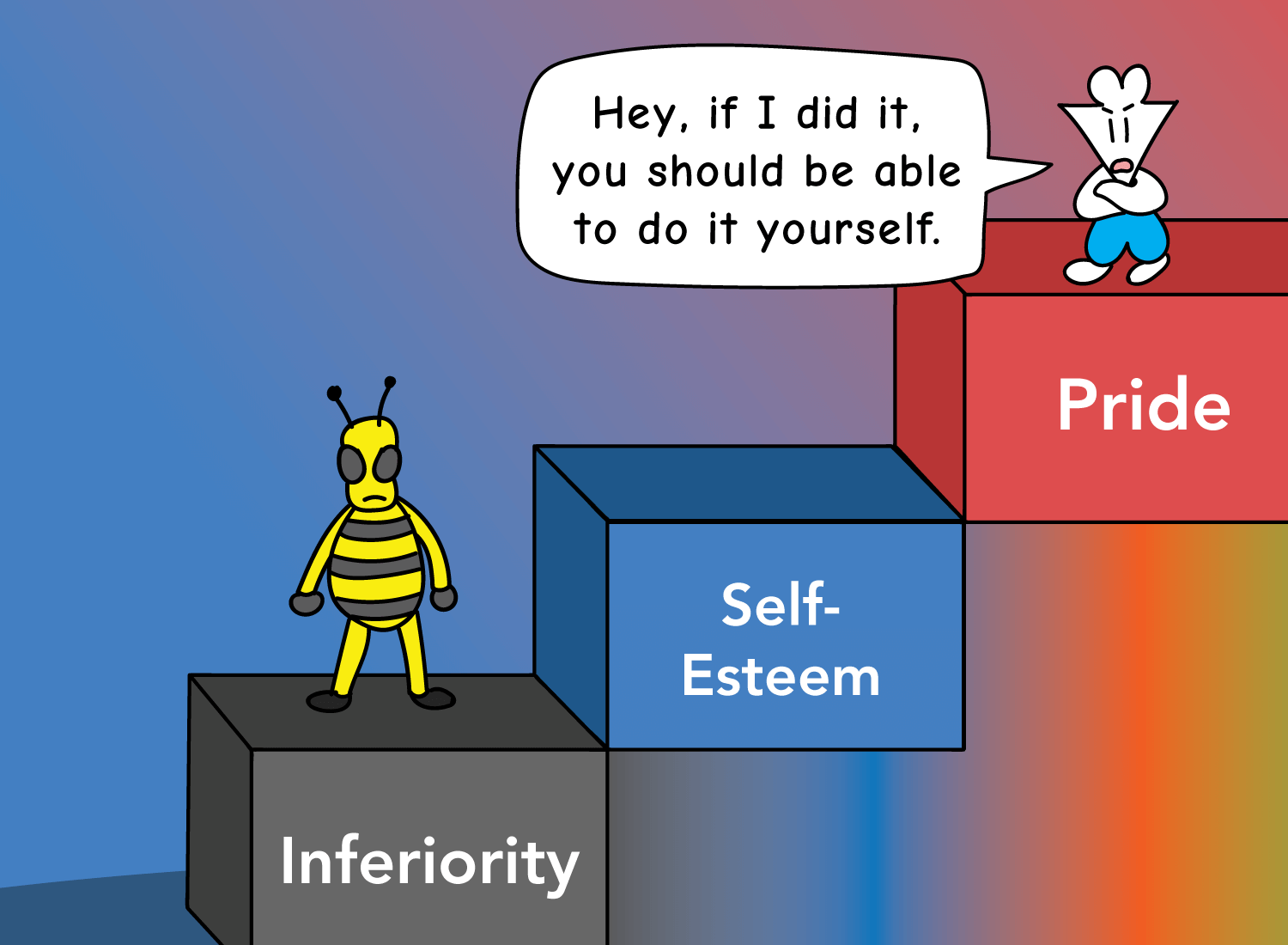

At the pinnacle of the staircase, we are proud of how our sense of agency produced the lives we have. We believe that it is through our own volition that we have achieved certain things, and we become grossly intolerant of anyone imitating us.

But this intolerance of imitation is yet another attachment to the sense of self. By seeing yourself as an entity that is imitated, you give further credence to the separateness of your being. If you believe that you are being copied, there is a separation in your mind between “myself” and “those that are copying me.” Or in other words, there is a clear “I” and “the other.”

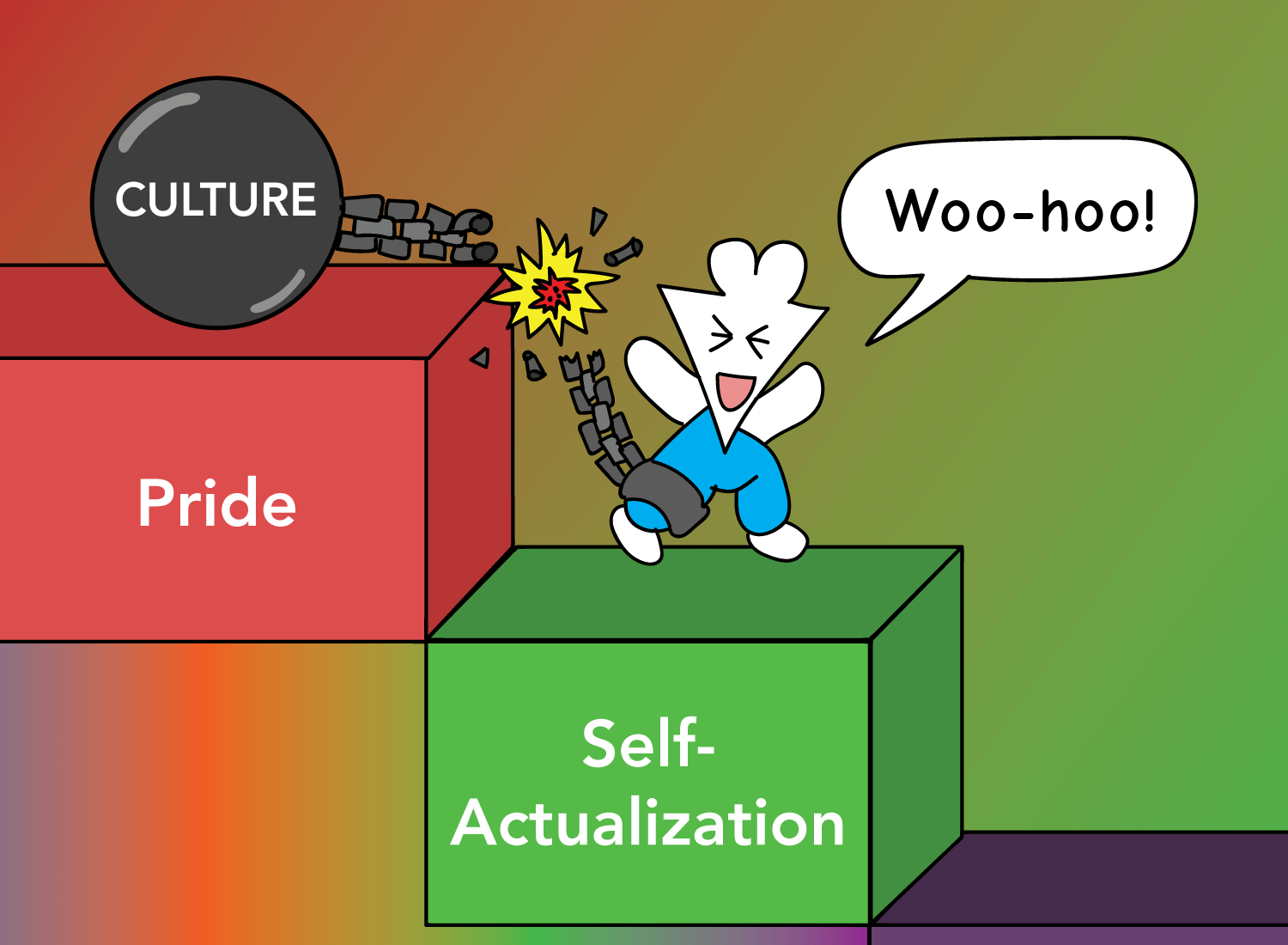

The problem is that we are socially conditioned to be protective of our identities, even though no identity is developed on our own accord. Culture is a clash of contradictory norms, and here are two conflicting ideas it loves to push:

(1) “Be yourself.”

(2) “Learn from others.”

#1 is an ode to authenticity, while #2 is a play to imitation. How can one be themselves while also seeking out another person’s knowledge? It doesn’t make sense, yet we somehow have to live in a society where these two values are forced to cohere.

Culture is full of contradictions like these (“have faith in yourself” vs. “question everything” is another), and the more we try to live within its bounds, the more confused we become. In order to limit the confusion, we develop defense mechanisms (like Thought Stop Signs) to accept certain norms without questioning them, because questioning everything would make the world far too open-ended and abstract. We need some element of certainty in order to function, and we trick ourselves into believing a select number of norms that give us a sensible model of reality.1

This is how someone can spend decades at a meaningless job. Or how someone can continue being friends with toxic people. They have bought into certain beliefs to help protect them from the uncertainty of the world (“this job gives me financial freedom” or “I have to always stick by my friends”), which dampens their capacity for growth.

At its core, self-actualization is the ability to transcend culture. It’s the awareness of the contradictory nature of norms, and that if you play within the bounds of culture, you will always have to choose one idea and ignore its equally true opposite. This type of black-and-white thinking is fertile soil for pride to develop, so you must break through cultural constraints for self-actualization to begin.

So what is the difference between self-esteem and self-actualization? What makes these steps symmetrical to one another, but not identical?

Well, both embody a sense of self, but do so under different conditions. Self-esteem is cultivated whenever you solve a challenge that gives you confidence in your capabilities. It’s the first move out of inferiority, so these challenges can be anything that gives you a sense of independence.

Self-esteem grew when you got that first paycheck from your job at the mall. When you graduated school. When you moved out of your parents’ place. When you found a partner.

Self-esteem is driven by your accomplishments and benchmarks of progress. It helps you realize that whatever life has in store, you’ll be able to deal with it yourself.

Self-actualization is different. The same challenges that grew your self-esteem may have no impact in this realm. This is because self-actualization is about fulfilling your potential, which has less to do with achievements and more to do with purpose. Getting a high-paying job may do wonders for your self-esteem, but it might make you doubt whether you’re being true to yourself.

This is because self-actualization must come purely from within, free from the gaze of cultural expectations. It is only through an honest audit of your interests and curiosities that will reveal what makes you feel truly alive, and what will dissolve all notions of identity you’ve developed over time.

The sense of self drops here because you’re attuned to what makes you feel authentic, giving you access to the deepest parts of consciousness. And when it comes to accessing the most of what our senses have to offer, there is only one gateway:

Creativity.

When we think of creativity, we tend to think of artists in funny hats painting stuff or performing songs. Sadly, this view has resulted in millions of people believing they’re not creative, or that they don’t have access to that part of their minds.

Here’s the thing. Creativity isn’t about making art. In fact, it’s not even about making something tangible.

Creativity is the process of losing one’s sense of self through the avenue of expression. It’s when the boundary between you and everyone else temporarily dissolves, and you feel most connected to our shared humanity. Some refer to it as a flow state, others call it The Muse, but ultimately, it’s the touch point we have with the deepest parts of our being.

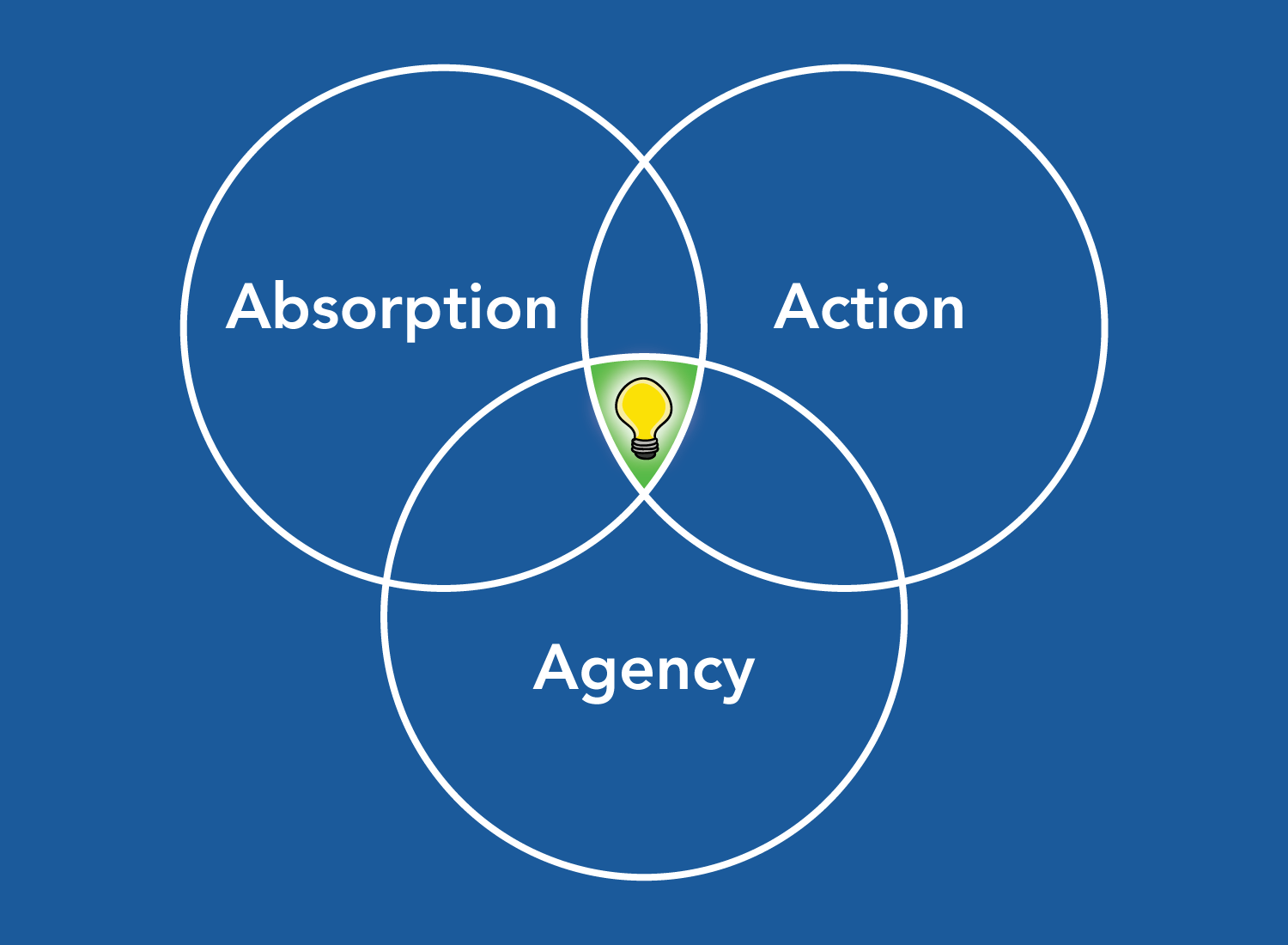

Creativity emerges at the intersection of what I call “the three A’s”:

Absorption is what our senses are engaged in at any given moment. We are constantly taking in data and information from the world, whether we are conscious of it or not. It can be as tangible as the tree you touched on your morning walk, or as abstract as the thought you had while taking a shower. In order for creativity to manifest, we need to have some foundational input that we’ve internalized from our day-to-day existence.

Action is fundamental because without it, there would be no vehicle for creativity to ride on. There needs to be some form of activity that converts the potential energy of what you’ve absorbed into a kinetic release. This is why binge watching a Netflix show isn’t necessarily a creative act, but if you’re inspired to make something afterward because of it, then it becomes a crucial step of the process. Simply put, action is what converts external inputs into internal outputs. It’s the ability to take what you’ve absorbed, imbue it with the characteristics of your personal worldview, and push it into existence.

Finally, we have agency. Agency is the most important piece of the puzzle because it implies that you’re pursuing something because you truly want to. There is a sense of purpose driving the endeavor, and this lens of meaning allows you to view your work as an exercise in creativity. Without it, you get the feeling that your work is just a job, and that there’s nothing too creative about it.

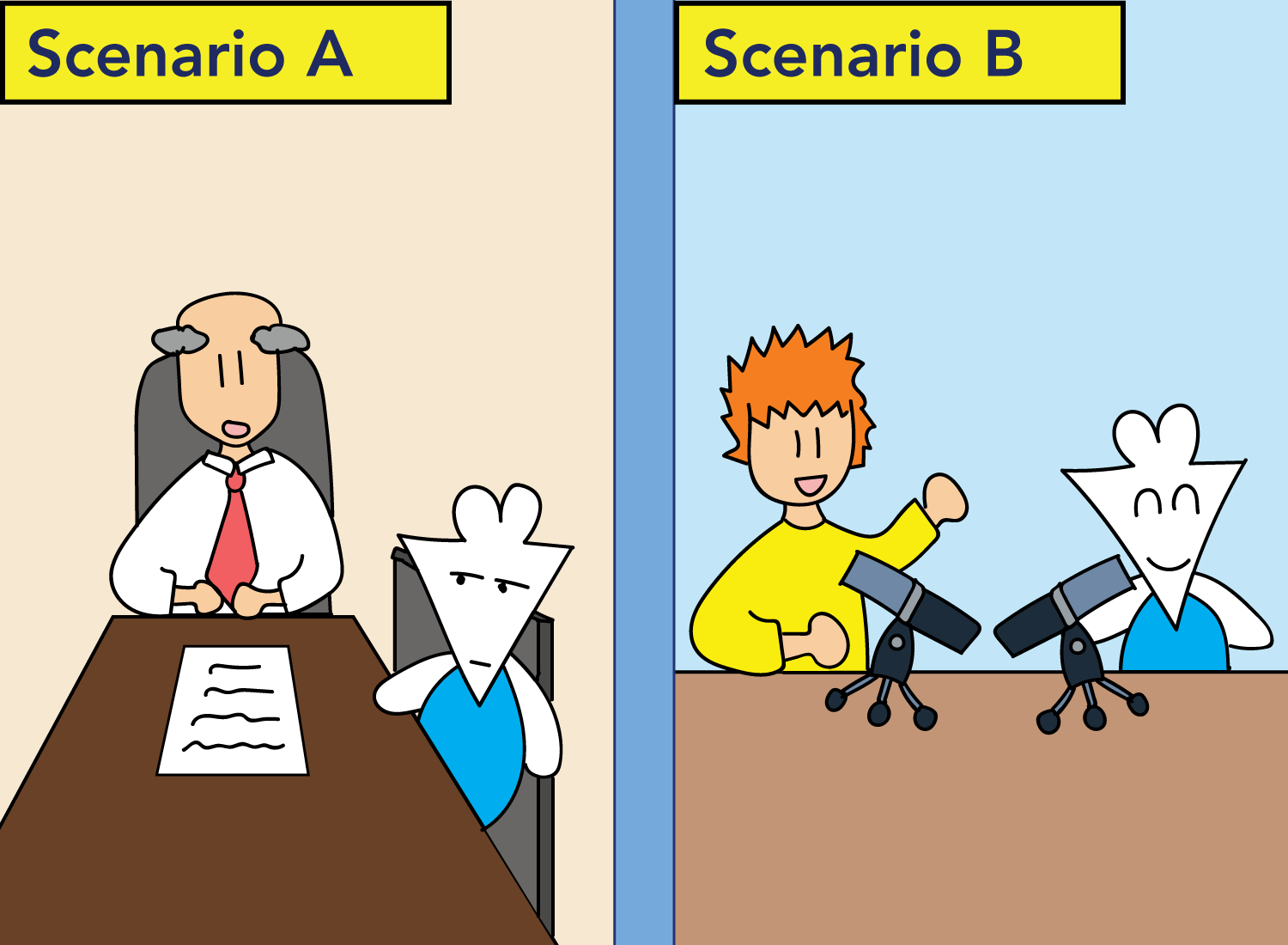

For example, take two scenarios that involve you talking to another person in real-time:

In Scenario A, you are having a meeting with your boss about a performance review you don’t care much for. In Scenario B, you are interviewing an exciting guest for a podcast that you recently started.

Both scenarios look similar from the outside, but on the inside, they are worlds’ apart. You will find nothing creative about the conversation in Scenario A, but you will likely see something creative about the dialogue you’re having in Scenario B. This is because you have a sense of agency – or personally directed will – toward having an interesting podcast conversation that is missing from the performance review discussion. There is a desire to make the most of the podcast project, which allows you to view it through a creative lens in turn.2

When I hear someone say “I’m not a creative person,” what I actually hear is, “I haven’t found something that will make me see things through a creative lens.” Creativity is often associated with art because art tends to be the result of human purpose. But in reality, being an employee in a cubicle farm can also be a creative endeavor to a person that finds meaning in that role. The same goes for any other profession that doesn’t fit in the stereotypical bin of “creative work.”

As long as you have agency over what you want to work on, it is only natural that creativity is unlocked with it. And with this final piece intact, we have everything we need to enter into a state where self-actualization can take place:

The sense of self decreases here because you are no longer fighting against a tapestry of conflicting beliefs. You know exactly what you need to do to feel most alive, and you can ignore the lure of cultural norms and expectations. When you’re creative, you are immersed completely in the moment, free from the memories of the past and the anticipations of the future.

There’s a reason why flow states are commonly described as the feeling of “losing yourself.” Or why time ceases to be pertinent when you’re fulfilling your potential. When absorption, action, and agency are aligned, it allows you to tap into a part of yourself that cannot be categorized into any particular identity or construct. All the boundaries that drive the separateness of your being slowly fade, and what you’re left with is a mind that simply exists and creates.

Self-actualization is what many of us strive for, and for most of us (including myself), that would be more than enough. However, there is a final step that we must acknowledge on our staircase, and even though I don’t know what it’s like to occupy it, I can make some guesses as to what it takes to get there.

From Self-Actualization to No Self

It’s quite annoying when you hear someone say something like this:

There are two reasons why we roll our eyes in this scenario:

(1) Losing your sense of self is still an incomprehensible concept to many of us, and

(2) By advertising that you’ve lost the self, you’re giving yourself an ego boost, which kind of proves that you still have it.3

So given these hurdles, how do you get anywhere near the final step on the staircase? Do you have to live the ascetic life, engaging in nothing but silent contemplation as you navigate the labyrinth of your mind?

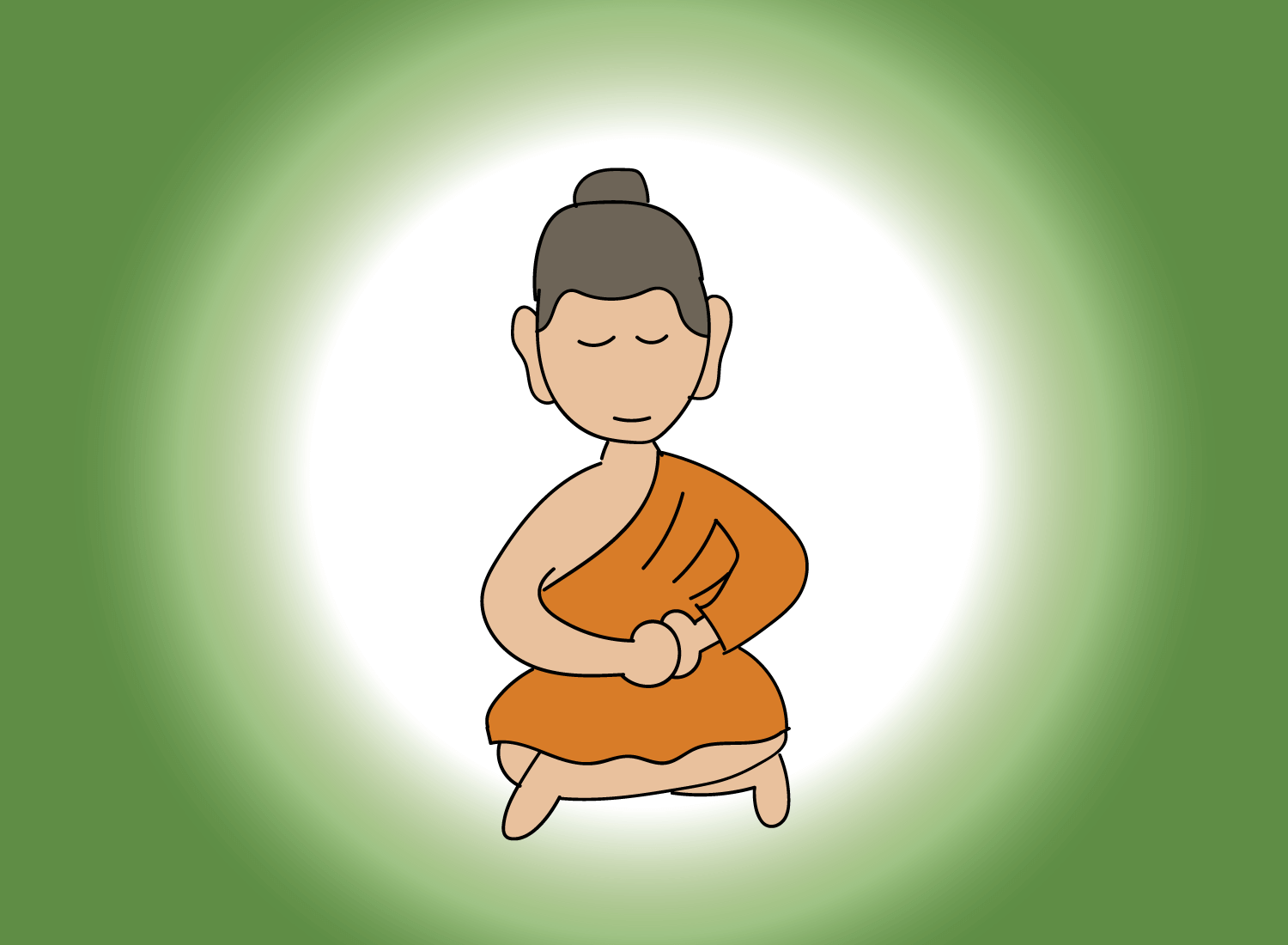

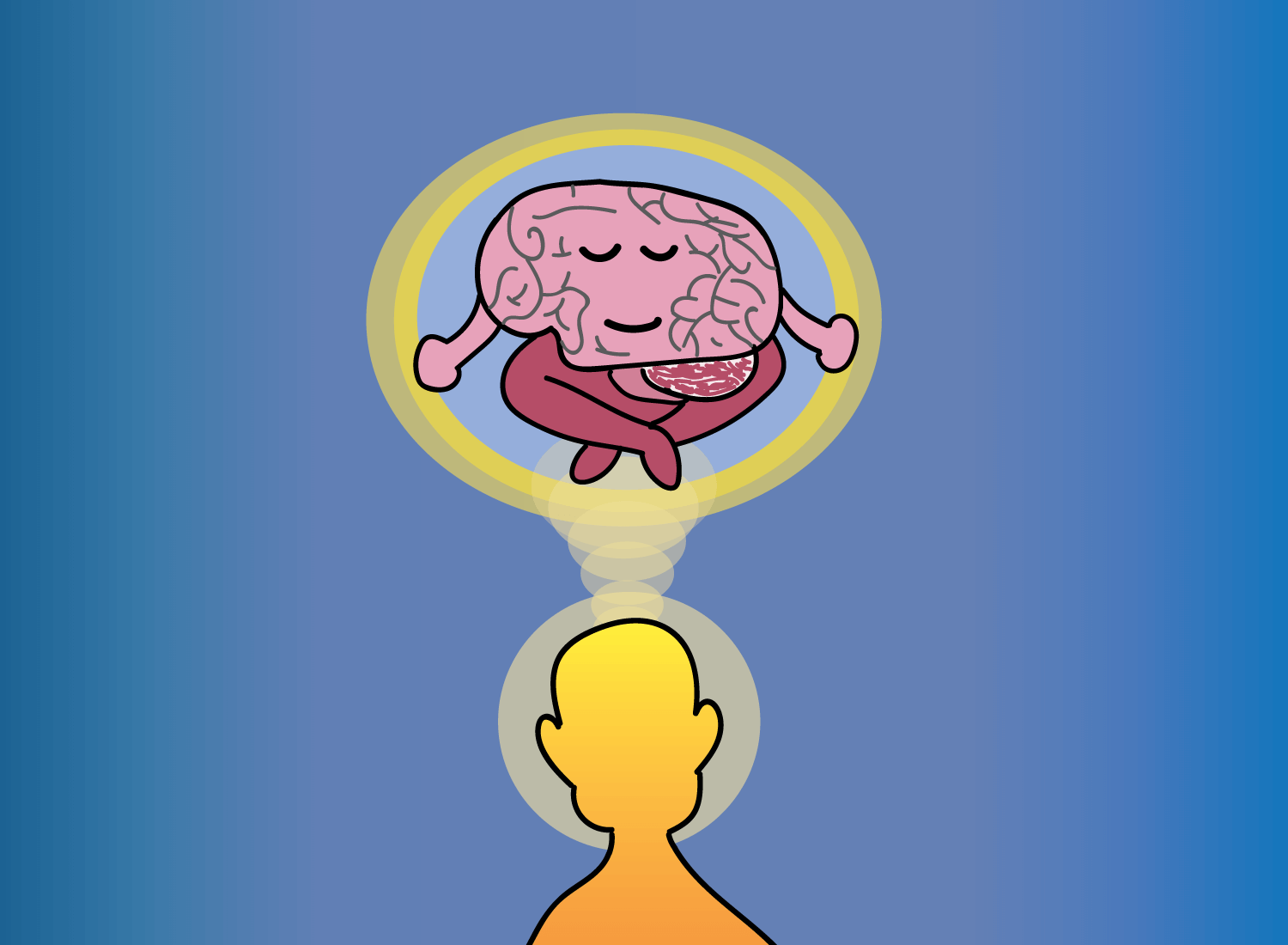

Well, to answer this, we have to tackle the first question of what it even means to completely lose your sense of self. And since this is something I’ve never experienced fully, I’m going to have to outsource my knowledge to the originator of the idea himself:

The Buddha.

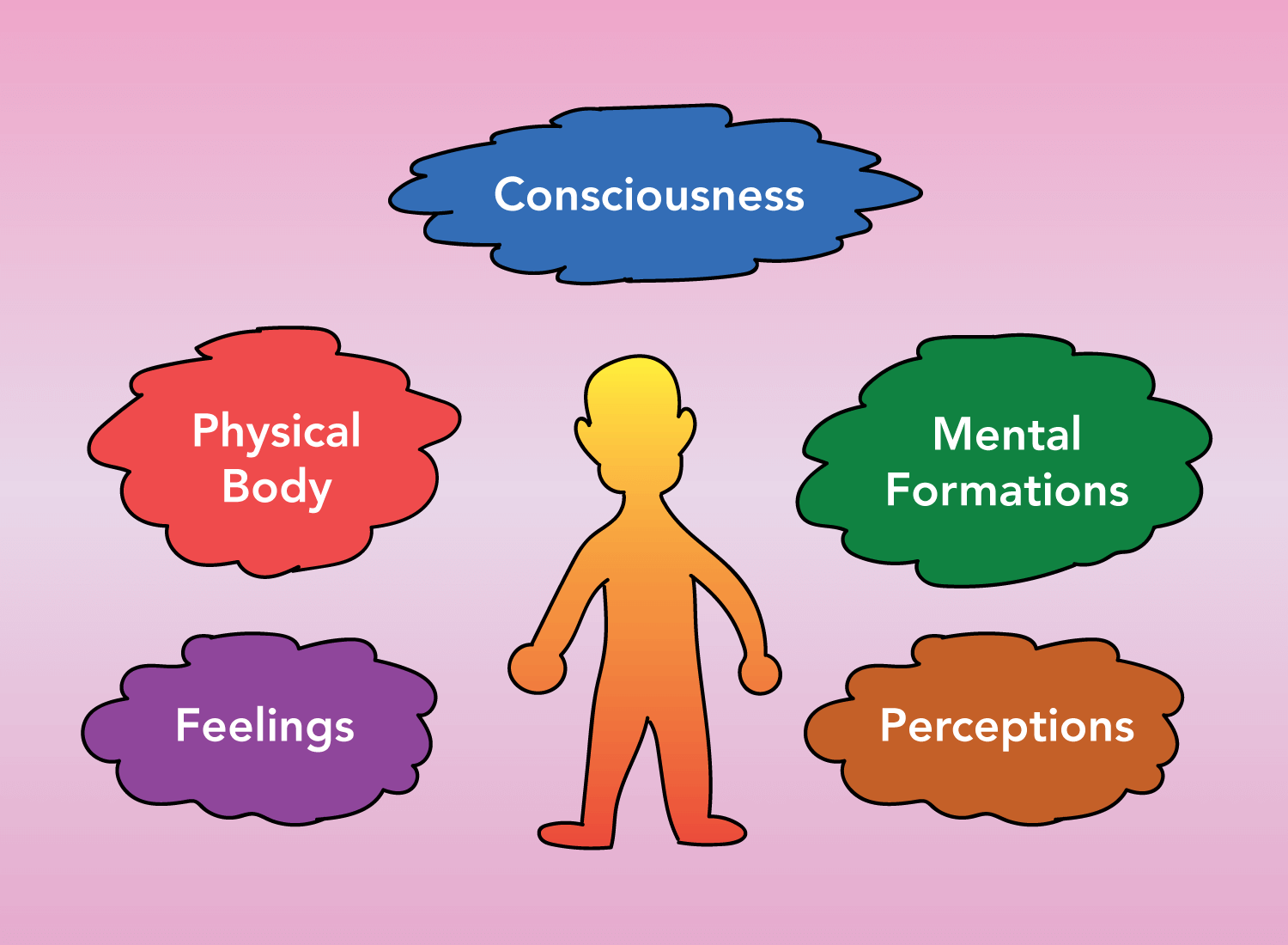

This idea of “no self” is known as anatta, and it was first addressed in the Buddha’s seminal sermon, Discourse on the Not-Self. In it, he provides a systematic examination of the five things that constitute a human being’s experience, which in Buddhist philosophy are known as the “aggregates.”

Here’s an illustration depicting what they are:

The Buddha then asks his fellow monks to go through each aggregate and determine where the sense of self might live. In which of these aggregates does the feeling of “you” as an independent agent reside?

The main lens he views this exercise through is control. When we believe we have a sense of self, we think we have agency over what we do. So the Buddha begins by examining the physical body, which he calls “form.” Do we have control over our bodies?

The instinct here may be to say yes – after all, if I want my arms to fly up in the air and wiggle, they will do just that.

But the Buddha – being enlightened and all – responded by saying that if we really had control over our bodies, we’d be able to eliminate physical pain the moment it arises. Additionally, we’d be able to change the shape of our bodies at will, and perhaps add another limb or two if we desire.

But no, we can’t do any of those things, meaning that control over our bodies is illusory. Therefore, the Buddha says that “form is not-self.”

He does this same exercise with our feelings as well. We can’t control what we feel, as we often have certain emotions that linger on when we’d rather not have them. The same goes for our perceptions, our mental formations, and yes, even consciousness. We can be aware of consciousness, but we have no control over what appears there at any given moment. There is no pilot in the cockpit guiding our thoughts – they simply arise and fade with no rhyme or reason, and this is the default state that we operate on.

However, this runs counter to all our intuitions. When I refer to myself in a conversation, there is certainly an “I” present and a “you” there as well. After all, being conscious is to be aware of myself as a living thing, navigating the world with the senses I have. By all accounts, it seems like my sense of self resides somewhere in my consciousness.

The Buddha seemed to have been aware of this point, and he elaborated on the topic of consciousness in another sermon. He claimed that in our default, unenlightened state, our consciousness seems to be “engaged” with the other four aggregates. It is fully entangled with our bodily sensations, our feelings, mental constructs, and perceptions. If we feel pleasure, we attach ourselves to that elevated state. If we experience pain, all our attention is directed to it.

But when we practice “no self,” consciousness slowly unravels itself from the other aggregates, and is ultimately liberated. It is no longer perturbed by any changes in sensation or experience, as it remains still regardless of what happens.

As the Buddha himself frames it:

By being liberated, it is steady; by being steady, it is content; by being content, he is not agitated.

Of all the explanations I’ve heard about losing your sense of self, this one is the most digestible. So much of our identities are tied up in what we feel, who we associate with, and how we perceive the world. But if we’re able to dissolve our ties with these things, then all we’re left with is the steady state of consciousness. It’s a full immersion in what is here now, with no room for the past and no regard for the future.

The reason why meditation is often associated with this endeavor is that it removes the element of striving. It is commonly referred to as “the art of doing nothing,” and this position of neutrality is the preferred platform to engage in one’s introspective journey.

However, most of you probably don’t want to spend half your waking days sitting in a cave with monks. You have other ambitions, other things that require constant action and movement. As we noted earlier, the desire to self-actualize is rooted in creativity, which is a kinetic form of expression. And as long as you’re on that path, it’s difficult to completely drop your sense of self.

When I think about cultivating “no self” in the context of our day-to-day lives, I find that it ultimately comes down to one thing, and one thing only:

The ability to remove our expectations.

An expectation is an attachment to a vision, and manifests in the word “should.” We should be working instead of relaxing. We should be married instead of single. These statements imply that there is a discontentment with the present state, and that there is some unfulfilled desire that fills the gap between who you are now, and who you want to become.

But of course, there is a utility to expectations as well. They often act as signposts to remind us to live healthy lives (“I should stop drinking”) or to fulfill our potential (“I should leave this job”). We refer to these as “good expectations,” but they still represent unfulfilled desires that imply discontentment with the present state. The question is about choosing which forms of unhappiness are worth having now to help position you toward a better future.

Inherent in any expectation – whether good or bad – is an attachment to this future “you.” And anytime there is a mental construct of “you,” there is a sense of self that you are identified with. According to the Buddha, this attachment means that consciousness cannot ever be liberated, as it is still “engaged” with the other four aggregates (unsurprisingly, mental constructs are one of them). So one of the most fundamental questions of human well-being have to do with this management of expectations.

Fortunately for us, some prominent schools of thought have tried to resolve this issue.

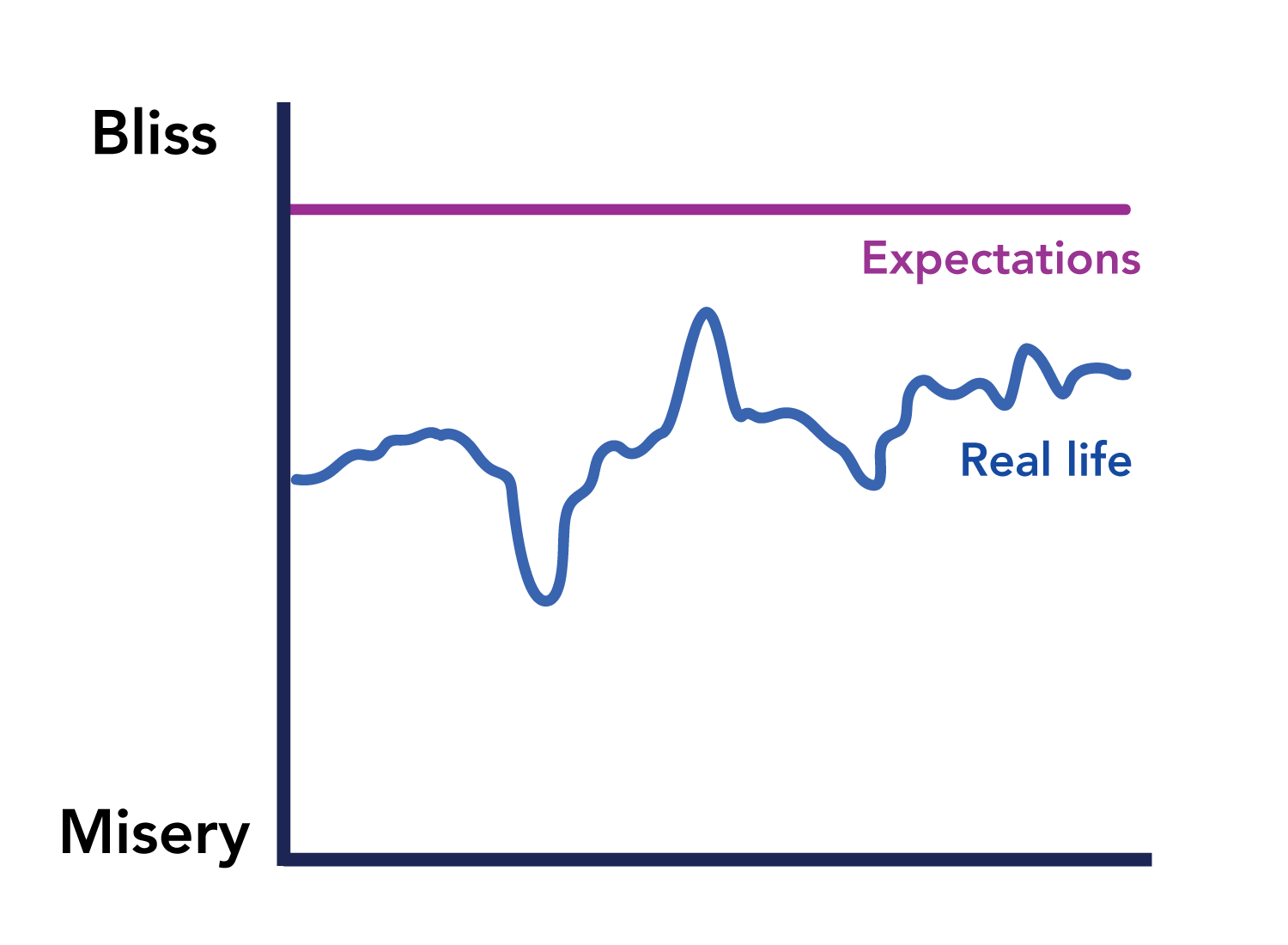

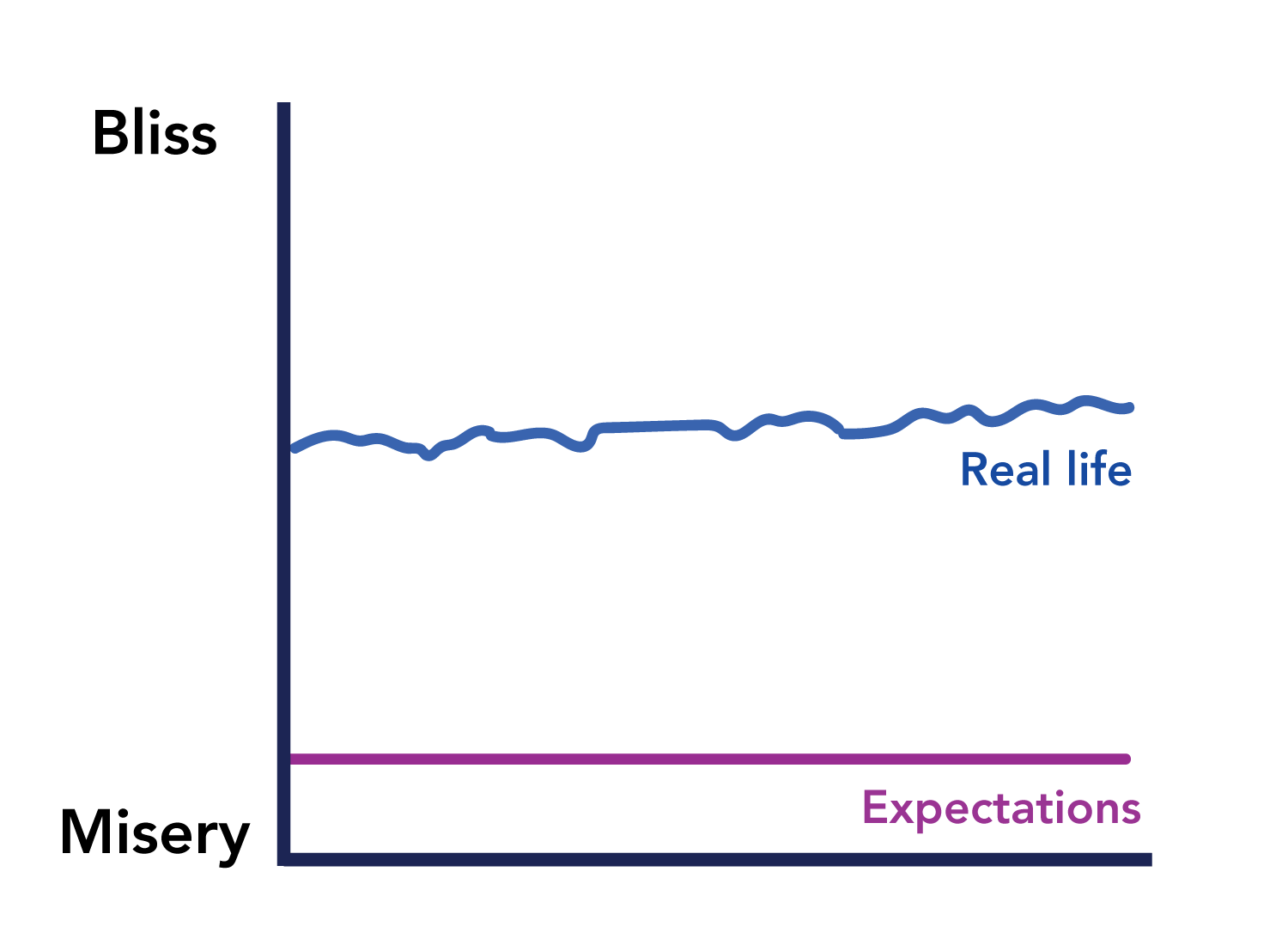

For example, the Stoics understood that most of us lived according to this graph:

They understood that expectations made good outcomes feel underwhelming and bad outcomes feel overwhelming. In order to correct for this, the Stoics proposed a framework that looked more like this:

In other words, if you expected the worst, you wouldn’t be surprised by anything. If you believed that your house was going to burn down, you wouldn’t feel distraught if it actually did. Similarly, if you knew that death was inevitable, there would be no need to fear it.

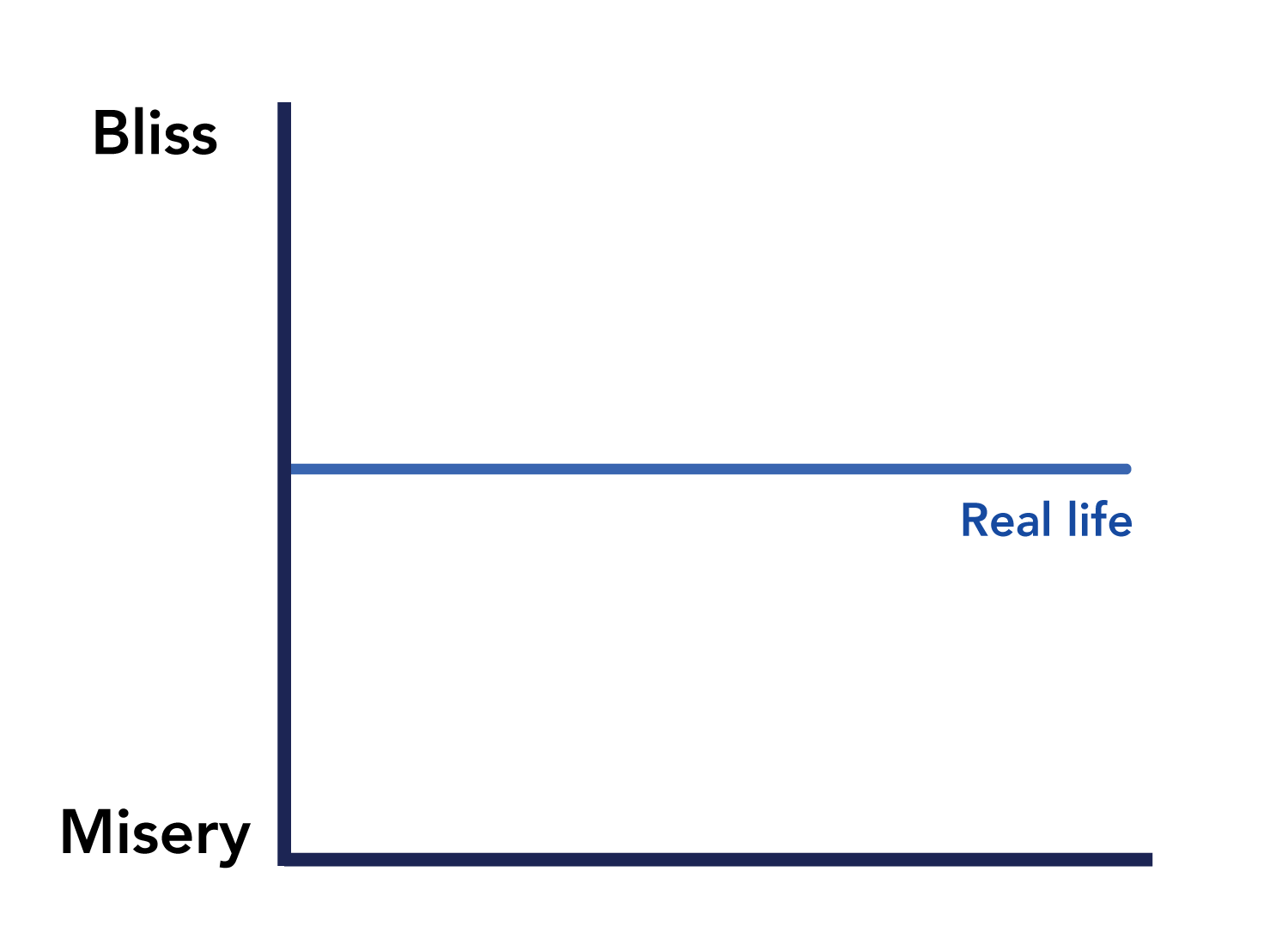

Another thing the Stoics taught was that our interpretation of events is what causes suffering. They claimed that events are always neutral, but it is our perceptions that make them either “good” or “bad.” By minimizing our interpretations, we create a smoother line of reality that allows for a more steady state of being:

I feel that the Stoics got the blue line of reality right, but the purple line of expectations wrong. While expecting the worst can be helpful from a self-improvement standpoint, it doesn’t do much to eliminate one’s sense of self. Viewing life through the lens of dismal expectations calls for a fixed worldview that you must identify with, no matter what happens. And as we noted earlier, a staunch adherence to anything opens the doors to pride.

This is where Buddhism re-enters the picture.

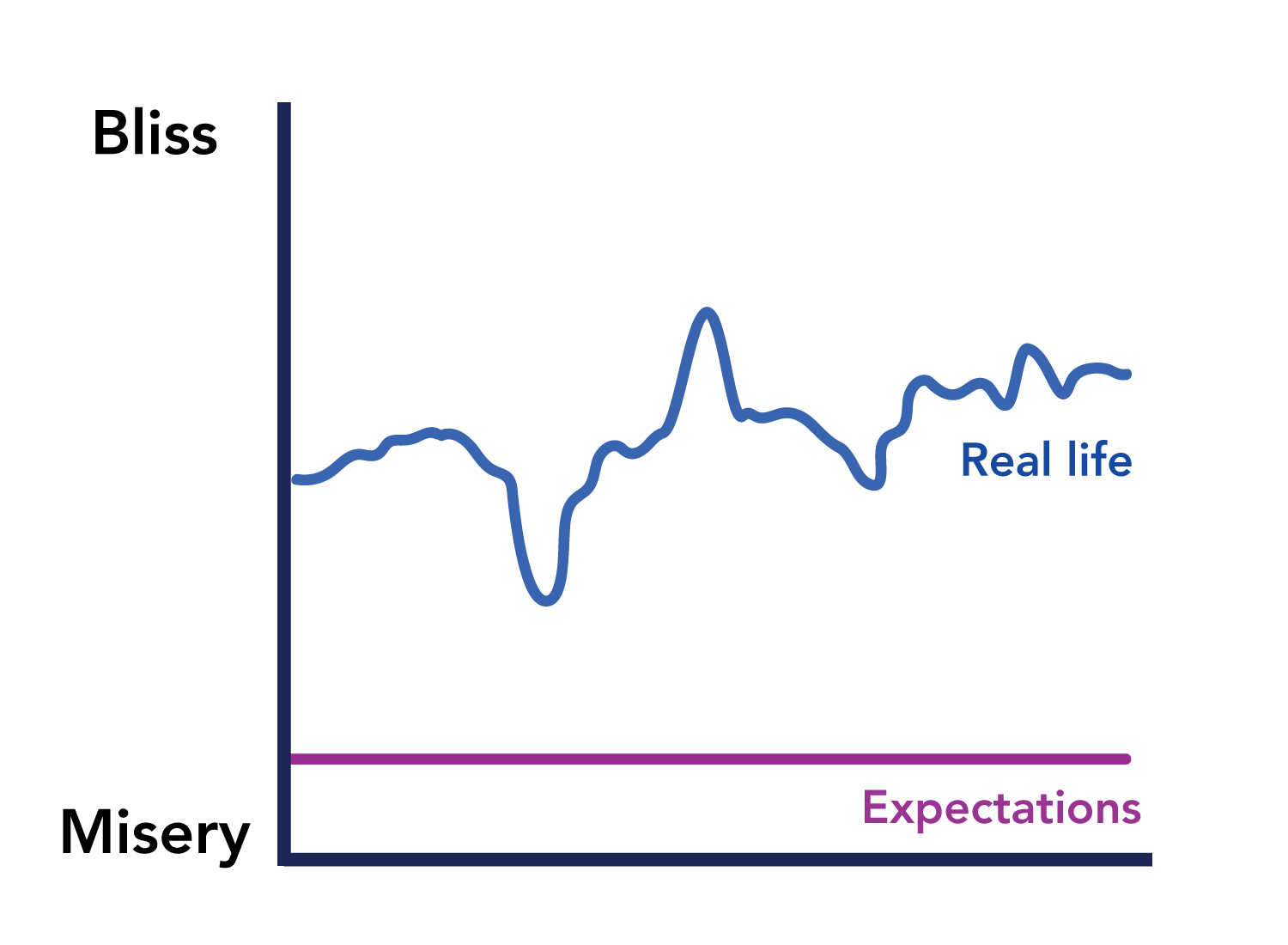

The very existence of the purple line creates a vision in the mind, or a notion of “what is to come.” The only way to fully remove the sense of self is to have equanimity with the present state of life, and to have no expectations whatsoever of a future state. Or in the context of our graph, we would have a steady and neutral blue line, accompanied by the complete absence of the purple line:

It is only in this situation where the Buddha would say that consciousness is “liberated.” Where it no longer holds any attachment to the senses or a specific mind state.

Consciousness can simply exist, free from any disturbance in body or mind.

As I said earlier, I don’t know what it’s like to be on this final step. I’ll be the first to admit that expectations are embedded into so much of what I do, especially because I now have a daughter who’s going to grow up in an increasingly changing world. From my work life to my personal life, there’s so much to consider as I navigate the demands I have on my time, energy, and attention.

However, there may have been moments where I got a slight feel for it. Perhaps there was a second or two during a meditation session where all thought came to a standstill. Or when I took a psychedelic and marveled at the sunset. Or when I was writing in my journal with no expectations of what would come out on the page.

The paradox is that even if you lose your sense of self, there is no self there to realize that you’ve lost it. There’s no real way to consciously know that you’ve touched this step because there is no “you” anymore to feel the contours of that step.

So perhaps “no self” is not really a step to land on, but more of a concept to keep in mind as you live your day-to-day life. It’s the realization that cultural norms, social conditioning, and past experiences have created an identity that you have held onto. It’s knowing that beneath the haze of expectations, there is a consciousness that is free from it all.

And if it can’t be readily accessed, that’s fine. That’s pretty much all of us anyway.

All that matters is that you know that it’s there.

Finding Your Place on the Staircase

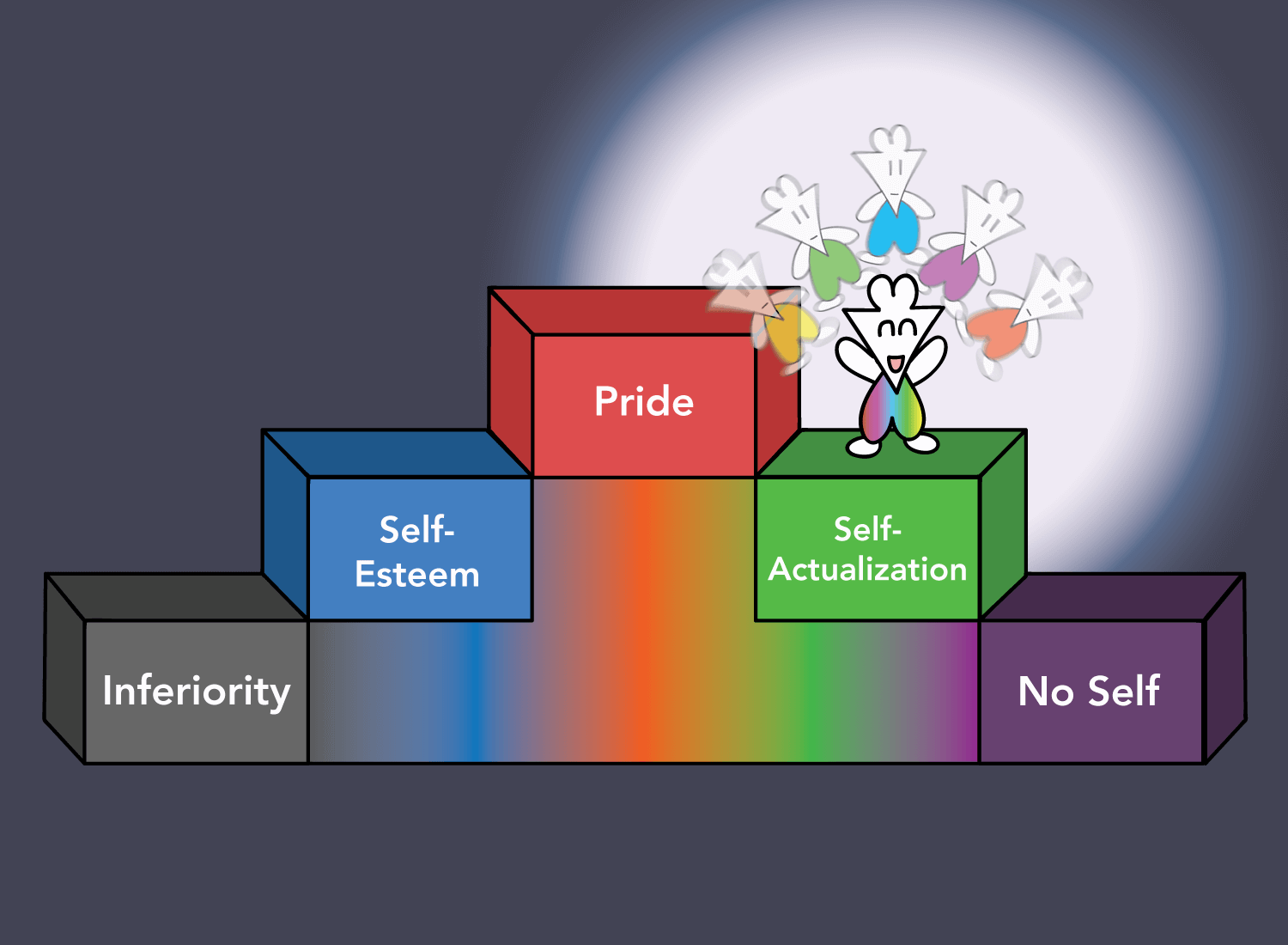

We’ve gone through quite a bit here, so let’s take a moment to zoom out and see the staircase in its entirety.

Seeing this, our initial impulse would be to try and get over to the right side of the diagram. After all, that’s where we tend to let go of our worldly attachments, and are actualizing ourselves in the most fruitful way possible.

But before doing this, we need to first pinpoint where we currently stand on this staircase. You won’t know where to go if you don’t even know where to begin, right?

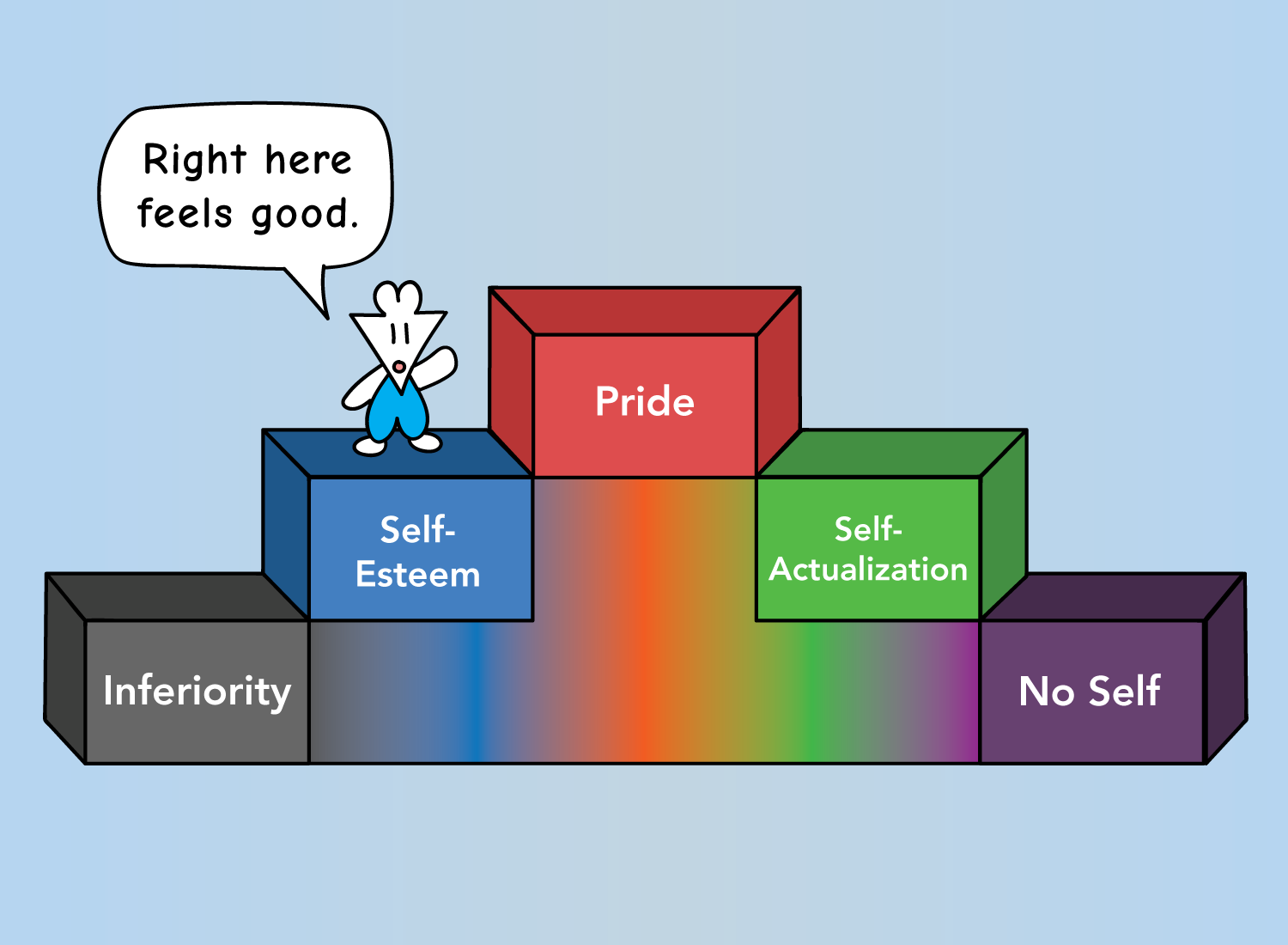

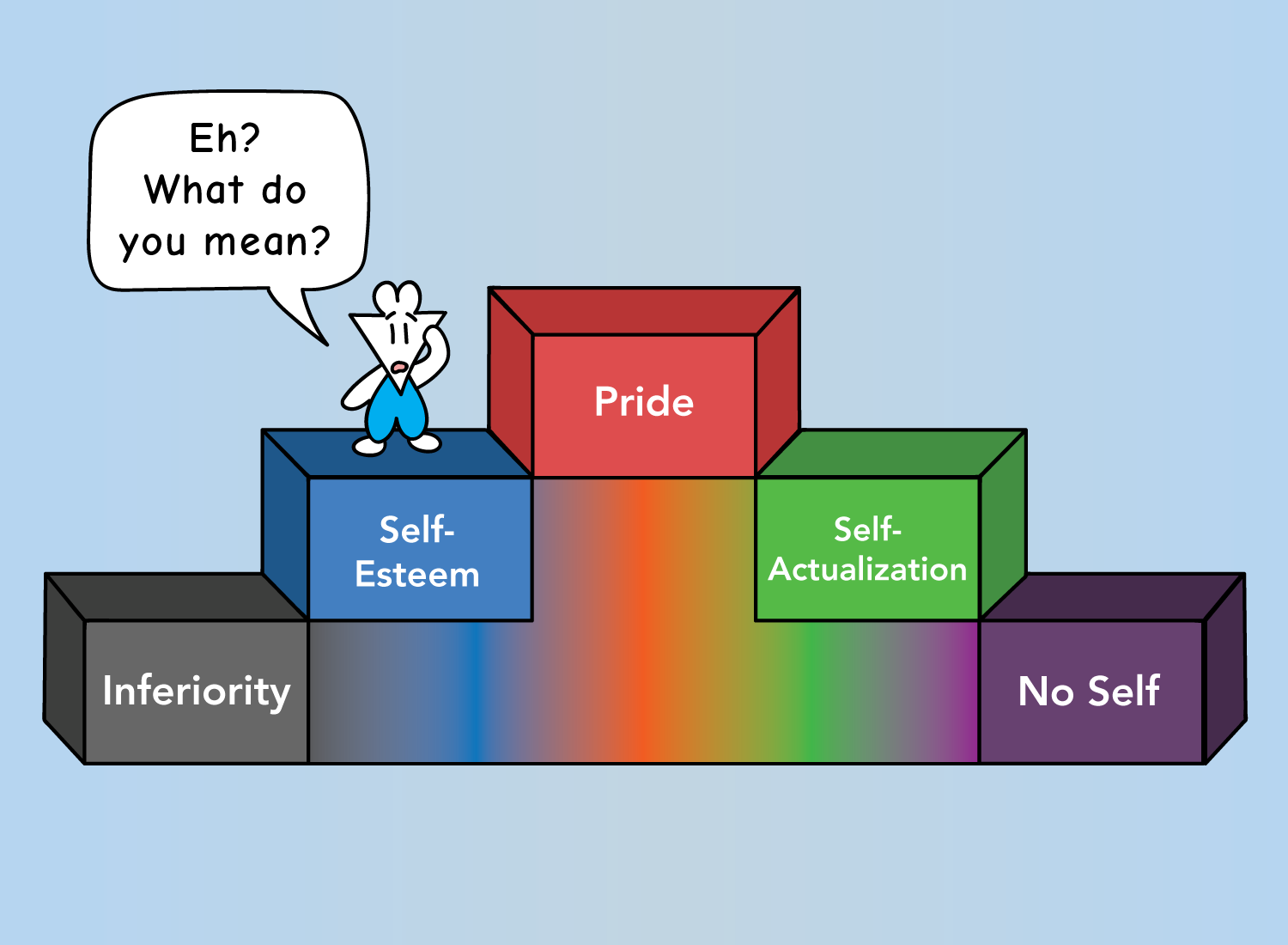

Let’s say that after reading about each level, your intuition tells you that you’re somewhere on the self-esteem step. You have a sense of independence and are aware of your ability to solve challenges, but understand that you’re not doing your best to fulfill your potential. You’re aware of your sense of self, but are open to hearing ideas that contradict your worldview, which gives you some distance from pride.

This starting point may seem obvious to you, and you might be quite satisfied with where you’ve placed it. However, there’s one important question I’d like you to consider:

Which version of your “self” did you reference while doing this exercise?

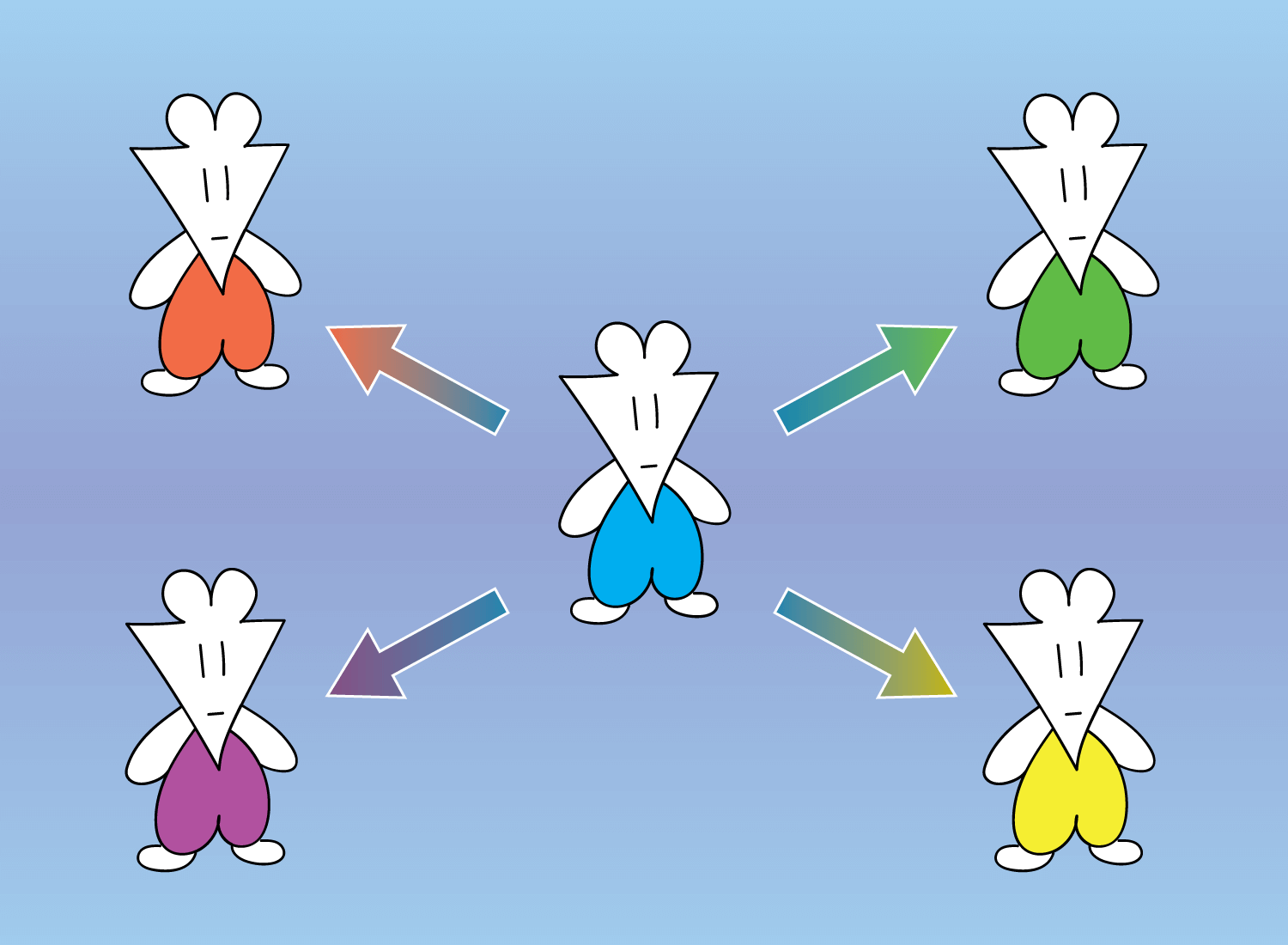

Here’s the thing. We like to think of ourselves as this singular, monolithic self navigating the world, but in reality, who we are tends to change entirely depending on context.

For example, there’s a “you” that acts a certain way when you’re at work, there’s a “you” that surfaces when you’re alone, there’s a “you” that shifts depending on the friends you’re with, and so on. Within one mind is a catalog of personalities, any of which can emerge based on environment and energy.

The tricky thing is that these various “selves” tend to occupy different steps on the staircase. Have you ever noticed how you can be so patient with your friends, but have a short fuse with your family? Or how you can be so intellectually rigorous with your work, but will vote for whichever candidate your political party endorses?

It’s entirely possible to be on the self-actualization step with your career, but also be on the inferiority step because you think your friends are further along than you. The reason why conflicting emotions like confidence and envy can co-exist in one mind is because so many versions of your “self” reside in it. For many of us, this segmentation of the self leads to a plethora of identities, all of which occupy different steps on the staircase.

When we think of personal growth, we like to cherry pick one or two of these “selves” and use them as the foundation for who we are. Unsurprisingly, they tend to either reside on the Self-Esteem or Self-Actualization steps, largely because it feels comforting and purposeful to identify with those areas.

But in reality, we are every single one of these identities. It might be convenient to ignore the parts we struggle with, but they will eventually emerge, whether we want them to or not.

The key to defining your place on the staircase is to choose which step you want to be on, and then to consolidate all the “selves” so they occupy that same position. You don’t want to take a mere average of them and call it a day – no, the only way to truly determine your place is to have equanimity across all possible environments and contexts.

You want to have the same level of patience for your father that you’d have for your friend. You want to have the same level of intellectual humility for any of your pursuits, regardless of how much you know. If you can commit to these baselines, you’ll immediately notice when a part of yourself is on another step, and you can reel it in before things get out of hand.

The failure to consolidate the sense of self is what leads to a disconnect in ideas and actions. This is why so many spiritual gurus end up committing heinous crimes. Or why great philosophers say one thing, and do another. These people conveniently segment their lives in a way that suits their preferences, and only advertise the steps they want others to see. But internally, their broken being is scattered across the staircase, conjuring suffering from not knowing who they really are.

The irony of the self is that in order to lose it, you have to know it well. In our default state, we don’t know who we are because the self moves along the tide of circumstance. The wind of emotion blows it one way, the current of happenstance takes it elsewhere. This makes us perpetually confused, resulting in a disconnect between who we think we are, and who we know we want to be.

But by consolidating ourselves to one step, we are keenly aware of where we aspire to be at all times. There is no question as to where we stand, no question as to whether or not our potential is being fulfilled.

It is only here where we can then commit to leaving it all behind.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Be mindful of the most common tool we use to define the sense of self:

Money Is the Megaphone of Identity

Much of who we are is dependent upon our relationship with uncertainty:

Equanimity – not elation – is what cultivates peace of mind: