What Makes Death Bad?

Welcome to the Courthouse of Philosophy.

The purpose of this court is to honor the art of open dialogue. We allow ideas to defend themselves and freely share their position, regardless of how controversial they may be.

We’ve had some exciting exchanges recently. Some of them include Communism vs. Capitalism, Religion vs. Atheism, and Free Will vs. Determinism.

But today, we have a rather special guest.

He’s been around for all of human history, and well before then too. He’s an ever-present force, and it is our awareness of his existence that calls so many of our beliefs into question.

Please welcome Death to the court.

Death is here to defend his name, as he believes it’s been unfairly tarnished throughout history.

The identity of the opposition party should come as no surprise. She’s also been around since the very beginning, and is what humanity values most. No accomplishment or no possession can be worth more to us than her.

Please welcome Life to the court.

Life vs. Death. It’s hard for any debate to get more substantial than this.

Since Death is here to defend himself, he will provide his argument first, and then Life will respond. Death can then respond to that counter-argument, to which Life can, and so on.

The goal for the court is productive dialogue, and an openness to hear one another’s views. Do the participants agree?

With that said, I will now excuse myself, and we will refer to the live transcript of the dialogue. We are so blessed to have an amazing reporter that can transcribe speech in real-time, so thank you so much for being here.

All right! Death, please provide your initial argument, and let’s get the debate started.

DEATH: Hello everyone, my name is Death.

My family business has been around for a very, very long time. I recently inherited it from my dad, who decided to give it up for the same reason his own father gave it up.

Simply put, this is a discouraging job. People hate us. Almost everyone does.

People set up elaborate rituals to keep us away. Religions have been set up to provide comfort against us. Science is now trying to tear our business down for good.

Well, today I’m here to defend myself and the family name. I’m here to argue for why I’m not bad, and to rationally explain why I shouldn’t be feared.

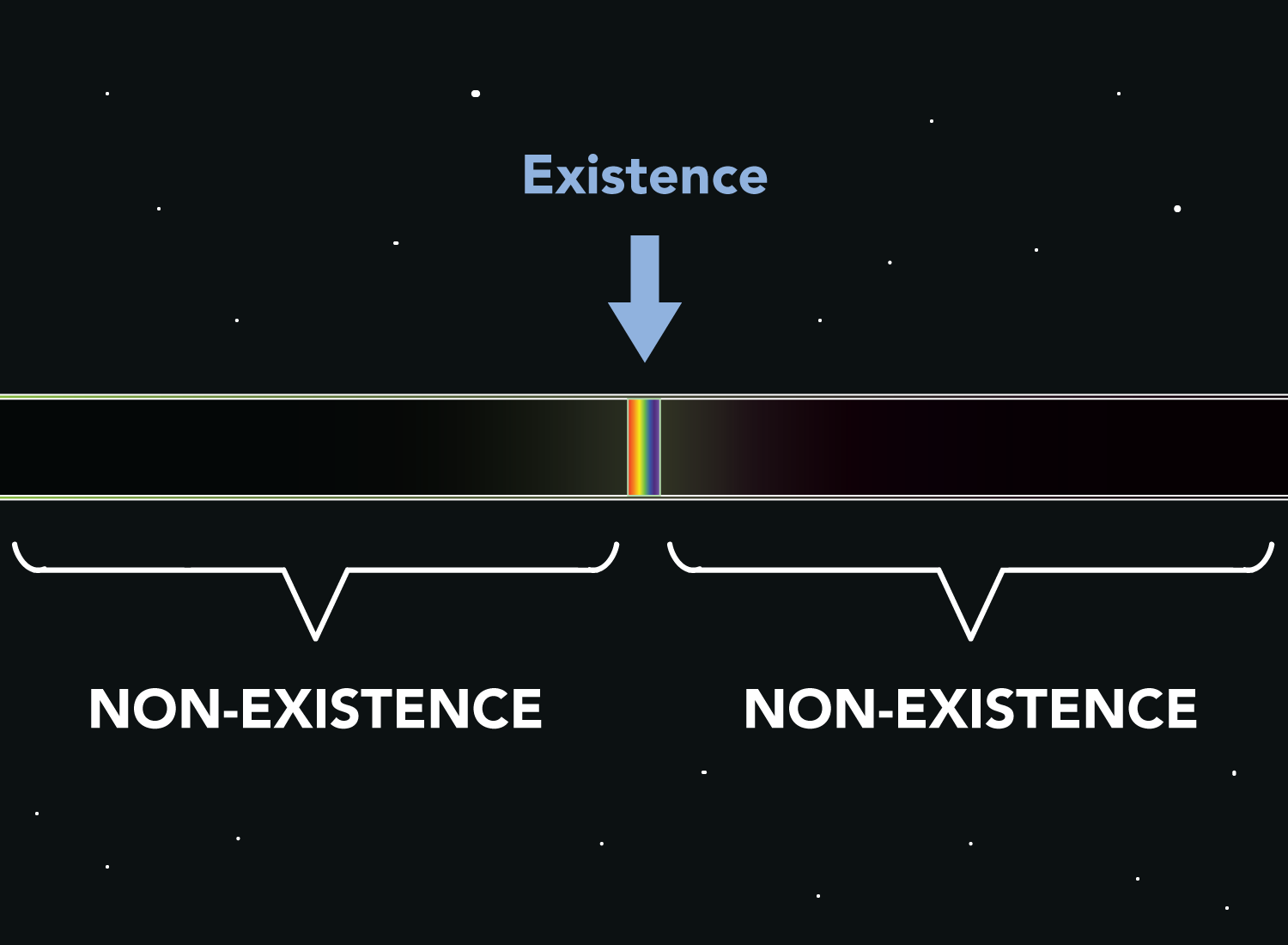

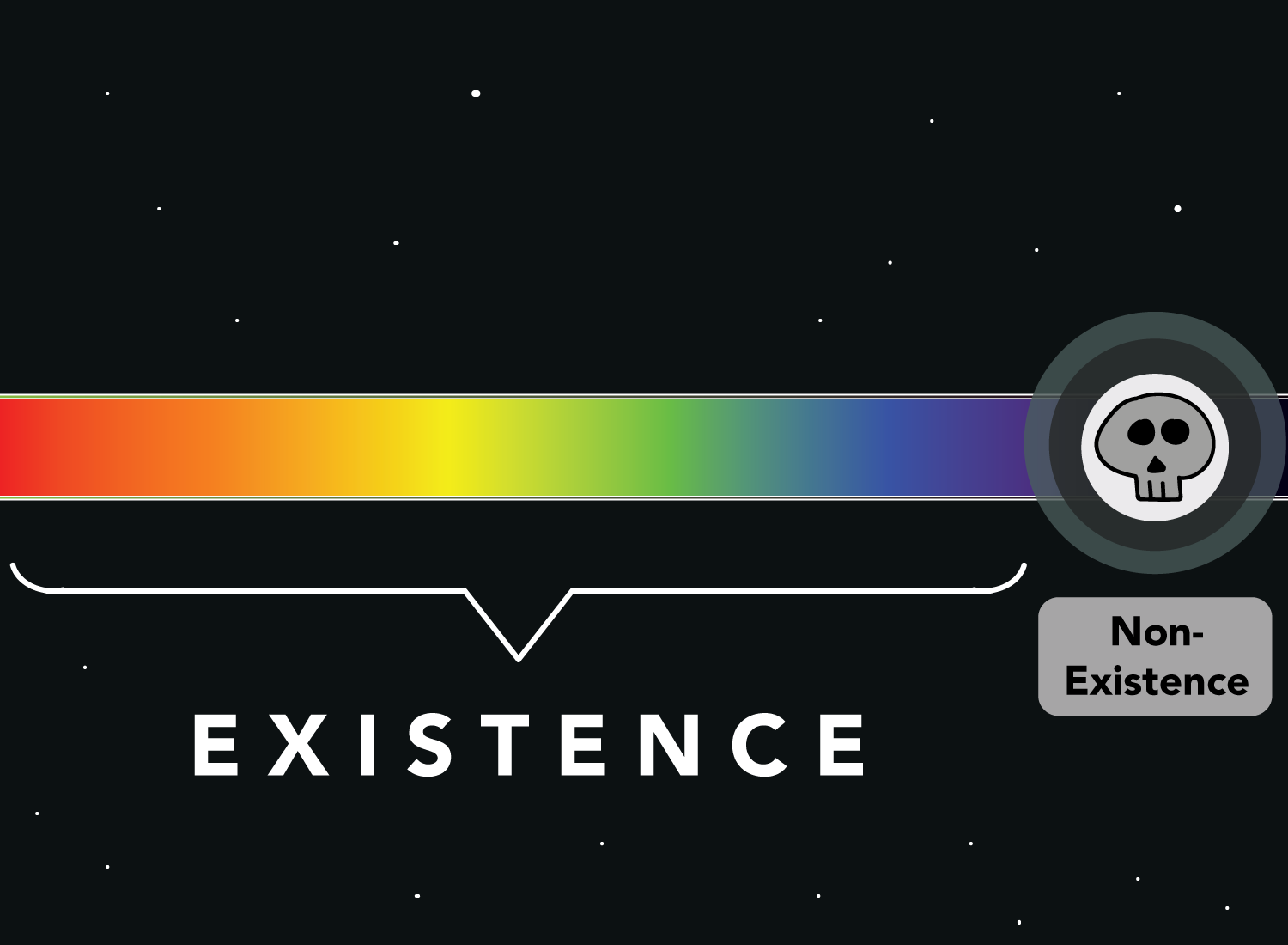

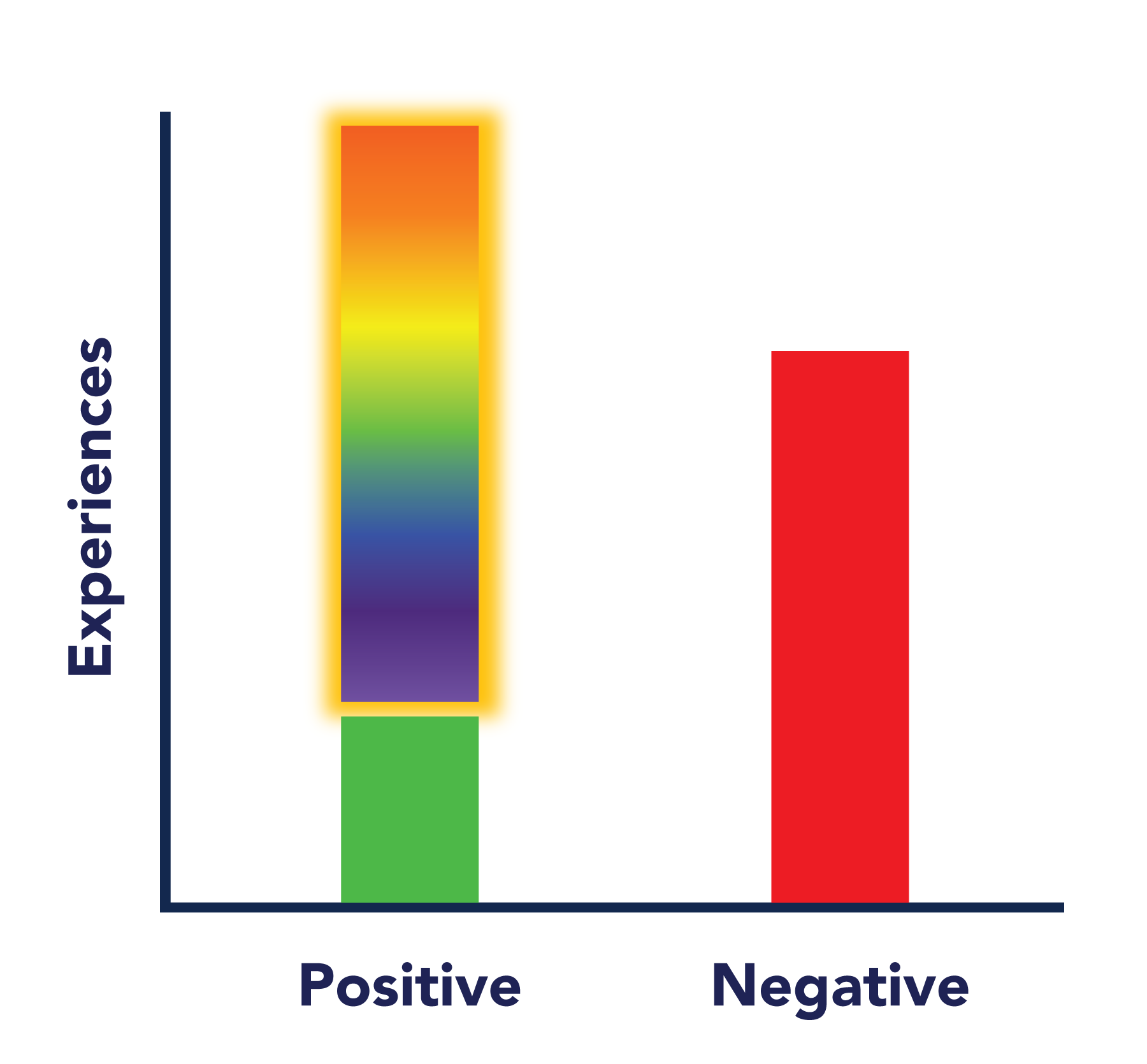

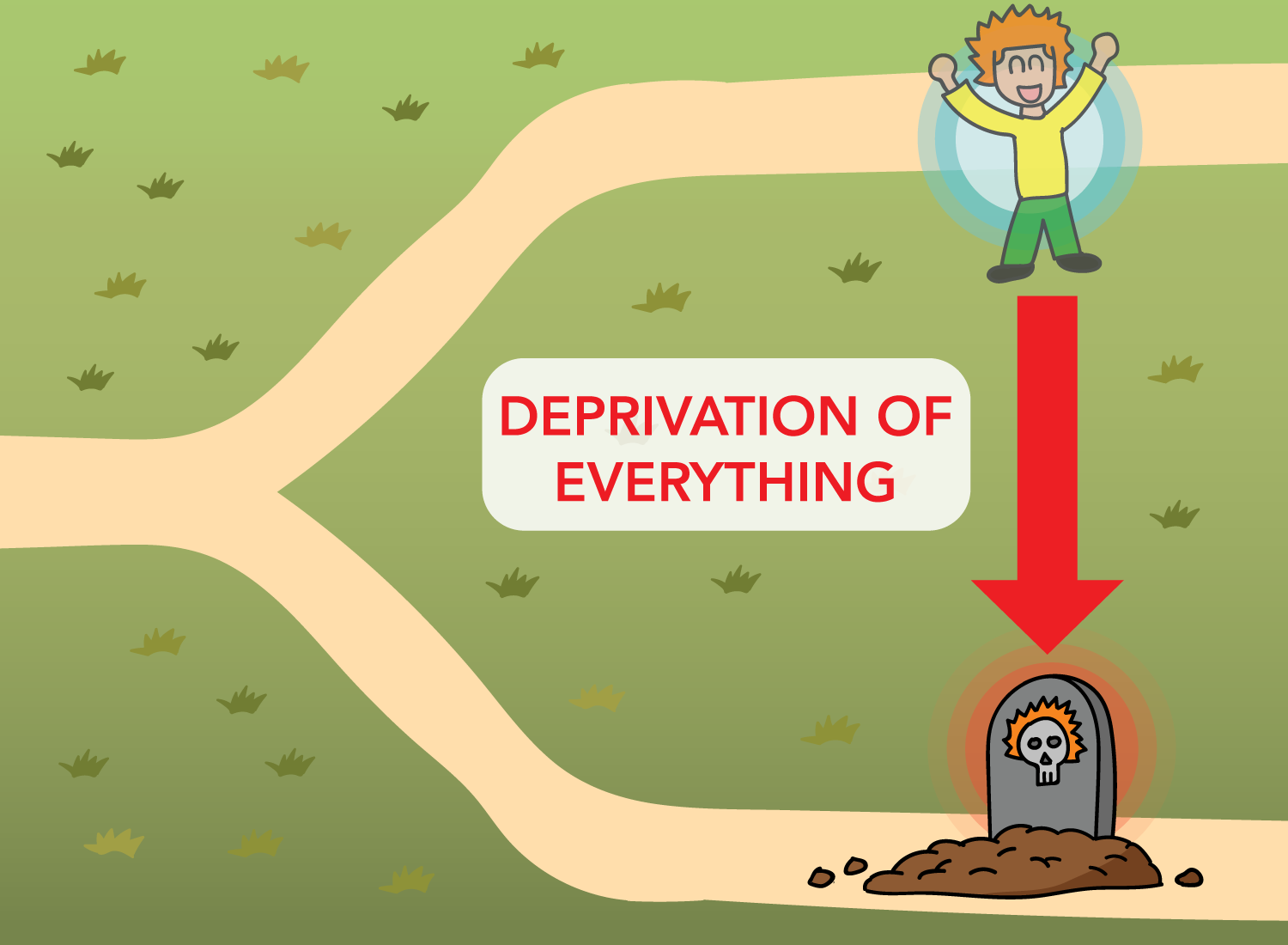

I will start by presenting this diagram:

If you think about it, my sole job is to take you into a state of non-existence. That might sound scary, but I want to remind you that you already know what this is like. You were in a state of non-existence for almost all of eternity, and you didn’t seem to mind then! So what’s the big deal of going back there again?

One of your esteemed authors, Mark Twain, seemed to have understood this when he said:

I do not fear death. I had been dead for billions and billions of years before I was born, and had not suffered the slightest inconvenience from it.

If anything, non-existence is the default state for all of you. There’s only a short blip on this ridiculously long timeframe where you exist, and then you return back to normality.

Remember what it was like before you were born? I didn’t think so. Well, that’s what it’s like after life. Non-existence… just like the billions of years before.

How is that a bad thing?

What do you say to that, Life?

LIFE: First of all, hello everyone, my name is Life, and it’s a pleasure to be here. Death and I are well-acquainted with one another and we’ve had many conversations in the past, but it’s great to have this discussion in a public forum like this.

Now I will address Death’s question.

His diagram justifies death by showing how inconsequential life is when compared to the billions of years of non-existence. It reduces life to a small blip that can be perceived as meaningless.

However, this view misses the most important point of all:

Everything changes once someone is given the chance to exist.

When you are born into the world, you are given the experience of life. Consciousness is turned on, and your ability to perceive is opened. You have access to your senses, and to all the emotions and cognitive capabilities that were previously unthinkable.

Here’s the fundamental asymmetry: Before existence, you had nothing to lose. But once you get a taste of existence, you have everything to lose.

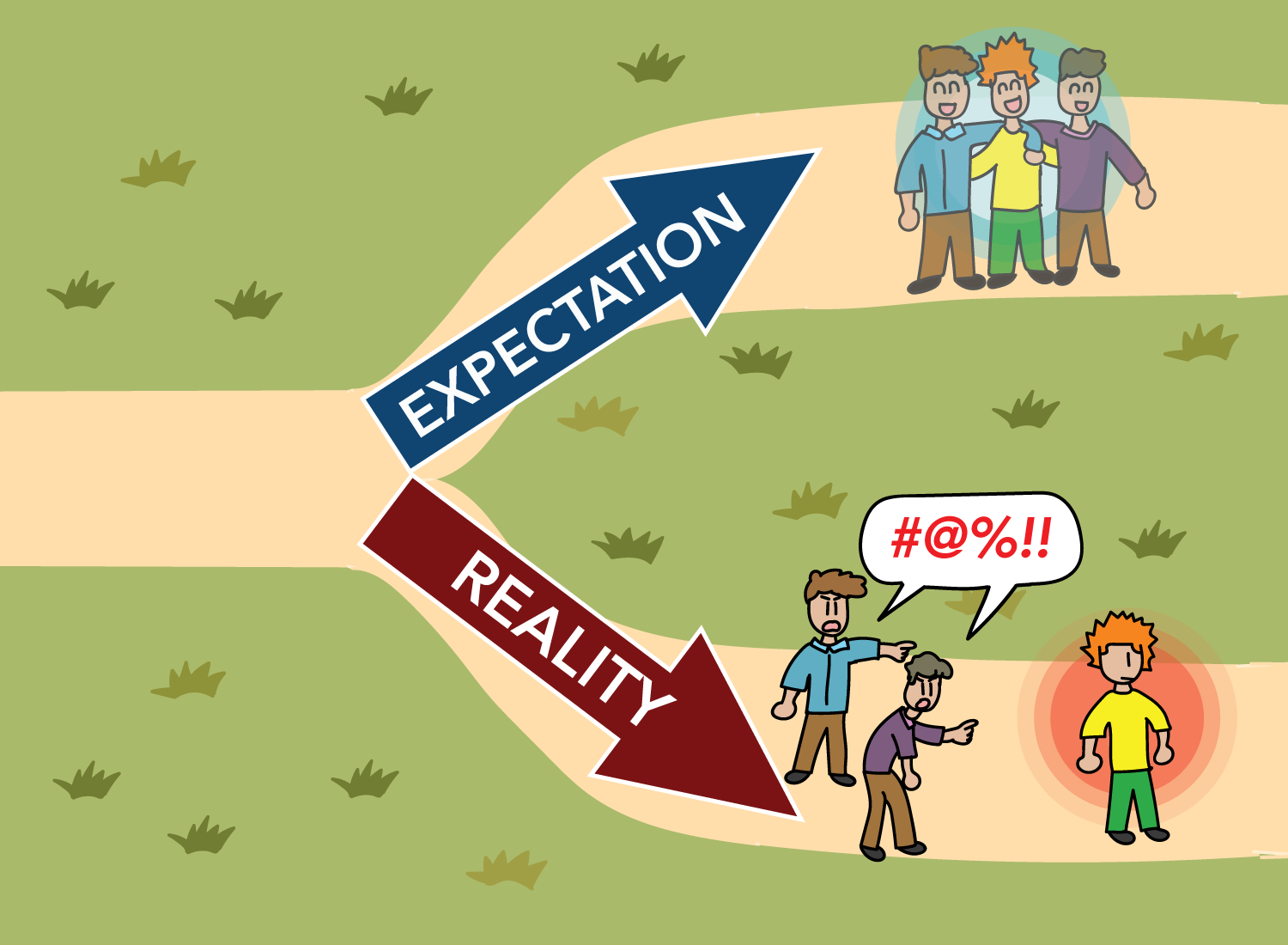

From Death’s perspective, his diagram looks like this:

But from the perspective of someone with life, their diagram looks like this:

People don’t care about the non-existence before them; the continuity of this current life is all that matters. Death is not some normal return to an awaiting void, it’s seen as a cancellation of everything people hold dear.

It is this deprivation of life that makes death a bad thing. It removes all the endless possibilities one could have had to see and experience additional things.

To the subject, life is not a blip on some eternal timeline. It is the entire timeline itself, and Death is the only thing that could abruptly end it.

DEATH: I hear you, Life, but there’s something you said that I need to address.

You tend to talk about existence as this inherently amazing thing. You always present it as a gift that is bestowed upon those who have it.

But what if it doesn’t appear to be that way?

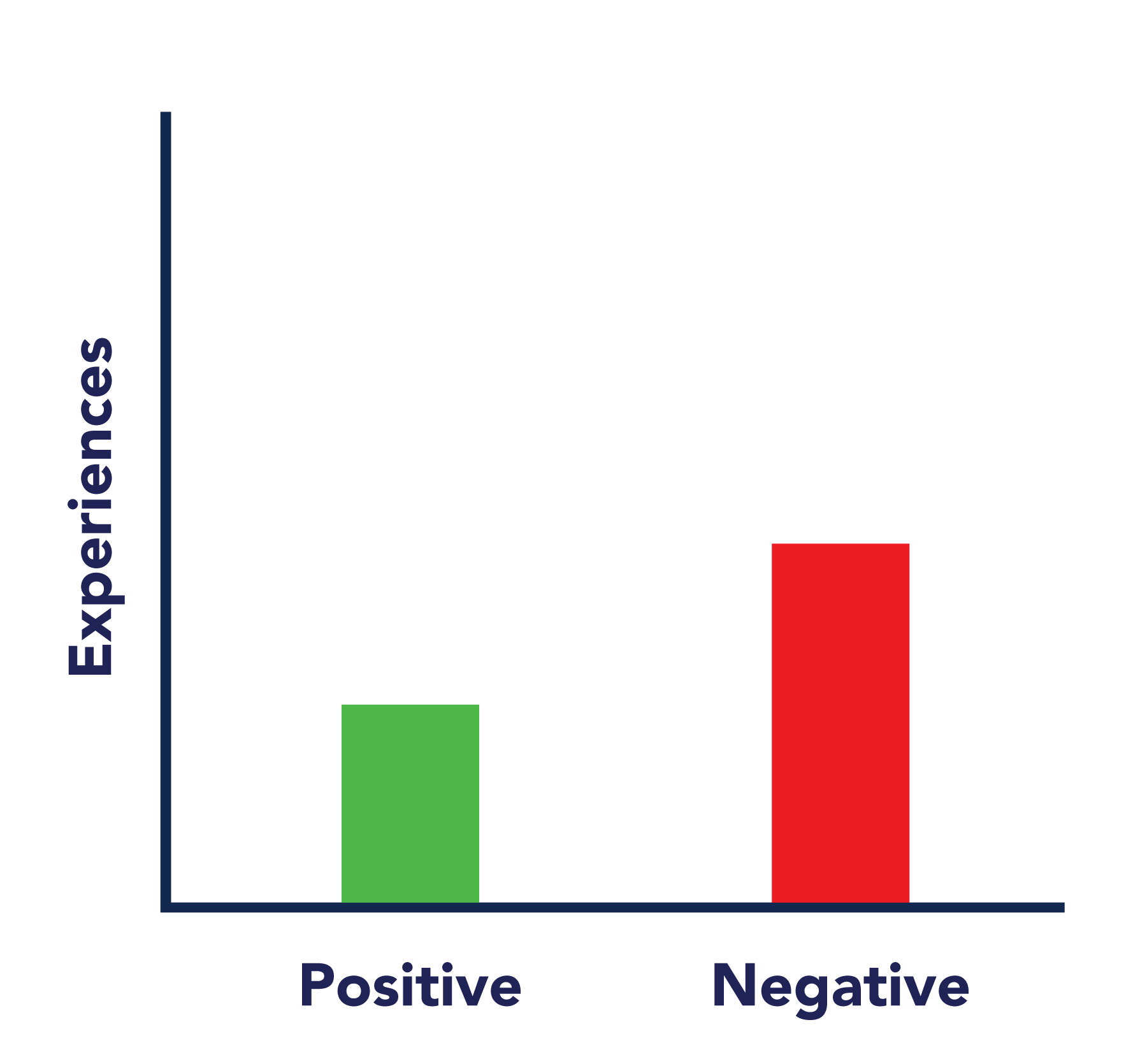

Let’s say that I went through someone’s life with a fine-toothed comb, and tallied up all the positive and negative experiences they had. Upon finishing this exercise, the results looked like this:

If a person’s life experiences yielded an overall net negative result, can you still say that this life is a good one? Would a life like this be an okay one for me to take?

LIFE: That’s a clever exercise, Death, but this is an instance where you’re trying to apply mathematics to something that requires philosophy.

The math may show that the number of negative experiences exceeds the number of positive ones, but philosophy reveals that there’s something fundamental you’ve excluded from the positive column.

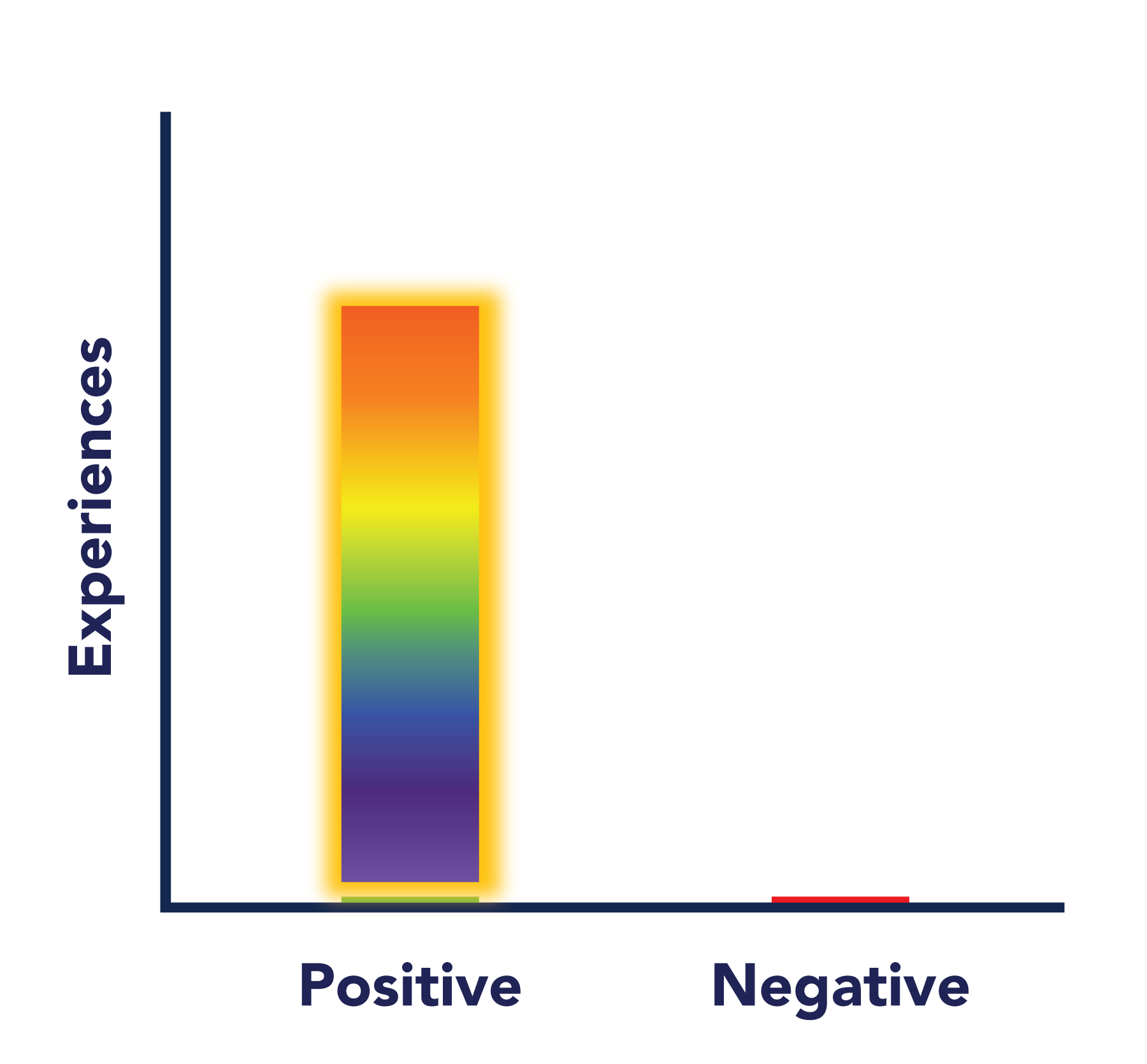

Let’s say that I bring in a bucket full of exactly fifty small containers:

I then ask you to look through all the containers, to count how many there are, and to show me what the biggest one is.

At the end of the exercise, you count a grand total of fifty, while you hold up this marginally larger container from the pile:

The real answer, however, is that there are actually fifty-one containers, and the largest one is the huge bucket that held the fifty smaller ones.

This is what it’s like to add up all the little experiences in life but to exclude the largest positive of all: the very bucket that carried these experiences to begin with.

Existence itself is this big bucket. It is the thing that holds everyone’s individual experiences, regardless of how positive or negative they might be. Life is worth living simply because we have been given the ability to live it.

Once we factor in the additional positive weight supplied by experience itself, the calculations will look more like this:

If we were forced to think in mathematical terms, we could think of this rainbow bar as a constant that is added the moment you exist. That’s why even a newborn baby, who has had no real positive or negative experiences whatsoever, will have a life that is imbued with positivity.

As its name indicates, this constant stays with a person throughout her entire life. So even if life appears to be more negative than positive, remember that this constant still makes it a life worth living.

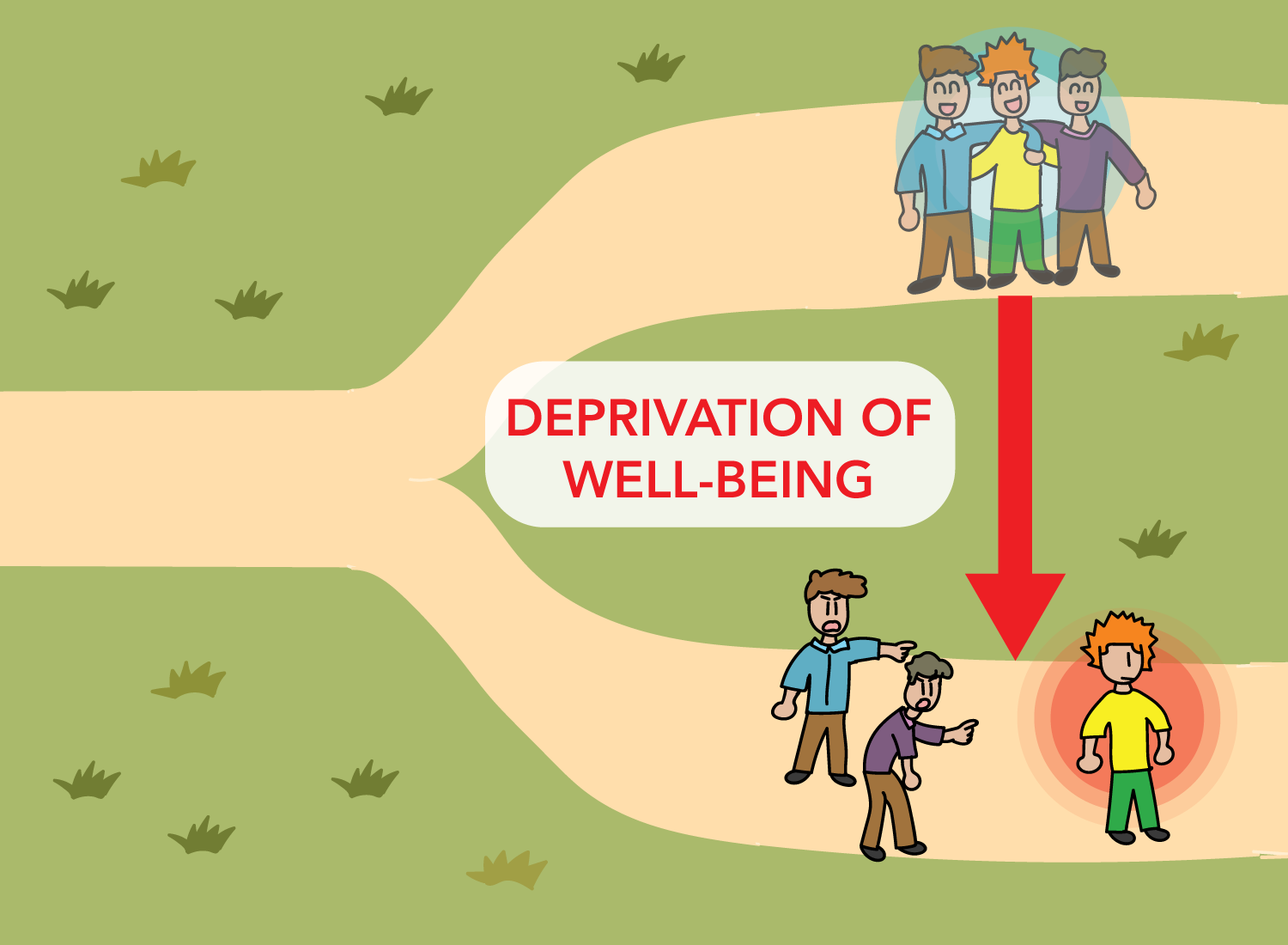

So yes, Death, my thesis still holds. Any time you come in and take a life, you are depriving that person of an existence that is fundamentally positive, which makes it a sad thing.

DEATH: Okay, let’s say that’s true, and the very experience of life is enough to skew the calculations toward positivity. But here’s something that never quite made sense to me with this narrative of “deprivation.”

When I come in and take a life away, I don’t think I’m depriving anyone of anything. In order for someone to feel deprived of life, they have to be there to feel that loss. But when that person is dead, he’s just… dead. He won’t know what it even feels like to have lost anything because he’s already gone.

This is similar to the notion of “what you don’t know can’t hurt you.” If you had a group of friends that secretly despised you but treated you politely to your face, that would be okay if you never knew about it. You don’t experience any suffering if you are none the wiser. Who cares if people talk smack about you if you never find out about it?

Similarly, why hate me if you won’t even be around to know what it’s like to be dead? By definition, you won’t be able to experience what non-existence feels like anyway.

LIFE: Interesting point, Death, but once again, I think you’re missing something important here.

In the example of your friends talking crap about you behind your back, you have to ask yourself what it would feel like if you found out about their betrayal of friendship. You’d most certainly be upset, but why would you be upset?

Is it the discovery of betrayal that made you upset? No! You wouldn’t be mad at yourself for finding out, you’d be upset because betrayal itself is a bad thing. Things like betrayal, ridicule, and deception are inherently shitty things, regardless of how unaware of them you may be.

If a person doesn’t know they’re being betrayed, what that does is create two divergent storylines: one where the person thinks all is well, and the truth, which is that his friends hate him.

The gap between these two storylines is the degree of suffering that is imposed upon the poor guy who doesn’t know any better. It represents the deprivation of happiness that results from his friends deceiving and betraying his trust.

When you say that the guy isn’t suffering because he’s not aware of the betrayal, you’re focusing too narrowly on his current state of being. You’re not taking into account how much he would suffer if he discovered the truth, and what that would do to his future expectations of friendship. It is the significant divergence of his storylines that is the real root of his misfortune.

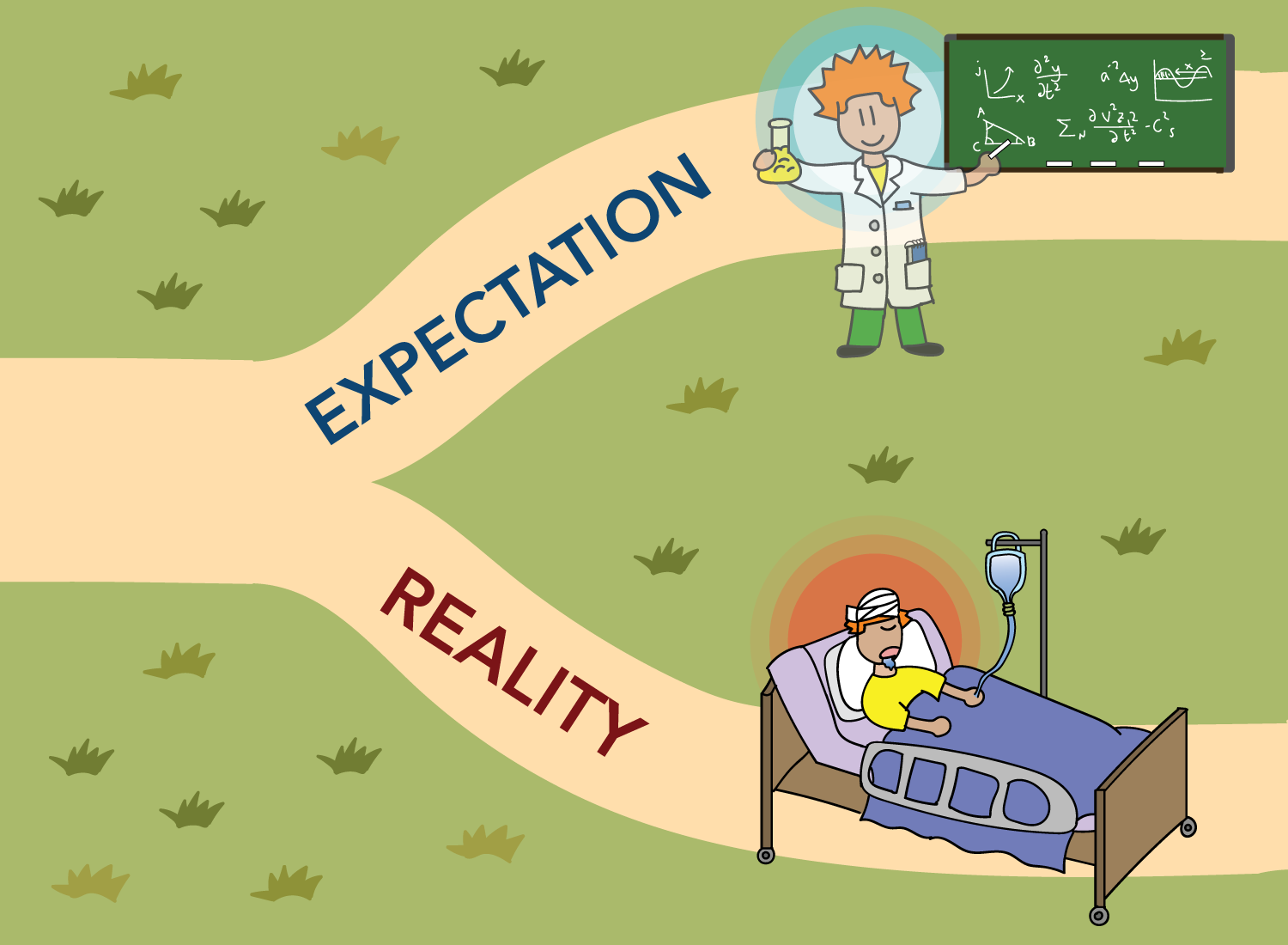

Now let’s take this conclusion and move it into the domain of death, or something quite close to it.

Let’s say that there was a highly intelligent adult who received a terrible brain injury, reducing his mental state to that of an infant. This man doesn’t feel any suffering because he’s in a contented state; he’s perfectly happy as long as he’s fed and his diaper is clean.

But no one would say that he is “in a better place now.” No, everyone would view this as a clear tragedy, a misfortune of epic proportions.

This is because the brain injury created two highly divergent storylines: one where the intelligent man continued to live his life and accomplish great things, and one where he has now become an oversized infant.

Being an infant itself is not bad, but the fact that this man’s mental state was reduced to that of an infant’s certainly is. Even though we see a contented man-baby in front of us, the reality is that he was deprived of all the hopes and possibilities that he had as an intelligent adult.

We don’t mourn who is in front of us now. We mourn the person that he was, and the person that he could have become.

This scales up to the ultimate deprivation: death itself.

When someone dies, you’re right, that person won’t know any better because he’s already gone. But that doesn’t make it any less of a tragedy.

When you attend a funeral, you don’t mourn the physical corpse that is in front of you. You mourn the loss of a person you remember, a person that still had more experiences to live. The body itself isn’t the object of your sorrow; it’s the person who was deprived of that body that is.

Non-existence cannot be perceived as a deprivation for the subject, but that doesn’t change the fact that it is a deprivation nonetheless. Since the experience of life is inherently a positive thing, taking that away would always be a tragic thing to do.

DEATH: Okay, I hear you on the tragedy of deprivation part, but here’s the most frustrating thing.

Whoever designed this system – whether it’s biology, physics, God, whatever – has created it in a way where I will always have to do this job! I will always have to take people away to non-existence, and everyone knows it.

Death is inevitable. It’s expected. It’s normal.

It’s going to happen to literally everyone, and no one in all of human history has ever escaped it. So how can my presence be a tragedy when I’m just a normal part of existence?

Think of it this way. Is it considered a tragedy that you can’t teleport? No, because it’s normal for you to not be able to teleport. Similarly, is it considered a tragedy that you can’t live forever? No, because it’s normal for you to not be able to live forever.

But regardless of what age I take someone – whether they’re 20 or 90, it seems to be a tragedy. Of course, if I take someone away at 20, it’s a greater tragedy, but taking someone away at 90 is still considered a misfortune.

This is the thing I struggle with most, and can’t seem to understand. How can something so expected and normal as my presence be so despised and feared?

LIFE: Interesting question, Death. Here’s my take on it.

As I mentioned earlier, once we’re born, everything changes. Our minds are turned on, our senses are opened, our experiences are formed. Existence has officially begun.

But as we grow older, something else happens, which changes everything again. We become aware of our ability to experience, and this allows us to appreciate the life we lead. We familiarize ourselves with the goods that life provides, and on top of that, we have no idea of when death will come to take them away.

This gives us the illusion that life appears limitless, even if we know that one day it will be gone. All we know is the state of being alive, and of all the ups, downs, sensations, and experiences that come with it. We can’t comprehend what it’s like to have that abruptly end, since non-existence is something we’ve never known.

Paradoxically, the normality of death doesn’t give any comfort because nothing about it appears normal. All we know is life and its contents, so stripping them all away is beyond anything we could imagine.

Whether it happens at age 20 or 90, the deprivation of life will always be some form of tragedy. In fact, you could increase the average human lifespan all the way to 1,000 years, and it will still be a misfortune if a person dies at 900.

Since there’s no lifespan long enough to make death a good thing, it looks like your arrival will always be the sign of a tragedy to come.

DEATH: Sigh… I get it.

Once you have life, it doesn’t matter how normal it is for me to come and take it away. That deprivation will still be viewed as a shitty thing to do, both for the subject and the subject’s loved ones. It’s just the way all humans are wired, I guess.

So I gotta ask… where does this put me? I don’t consider myself an evil, ya know. I’m just here because the system requires me to be.

I will always have to do this job, and I will have to pass this work onto my children as well. I mean, it’s possible that science does something incredible and eliminates the need for me, but assuming that doesn’t happen any time soon, what do I do? Do I just carry on, having people hate my guts as I do this work?

LIFE: Well, I think it’s a stretch to say that people despise you. Sometimes the knowledge of your presence inspires people to make the most out of life.

Knowing that their time in this world is limited makes people appreciate the moments they have with their loved ones. It also encourages them to engage in worthwhile work. If people were to live forever, it’s entirely possible that deep wisdom may be lost alongside their mortality.

We don’t know what it’s like to live in a world without you, and we shouldn’t pretend that we do either. My job is not to put a veil over you, it’s to reveal the lessons you can provide to those that exist today.

And trust me, there’s a lot to be learned from you.

DEATH: I appreciate that perspective – I really do.

Even though I’ve been around forever, people still have a hard time recognizing that, so it’s good to know that we’re in this game together. It’s only through your insight where I can understand how people perceive me, so it’s great knowing that I can approach you with my thoughts.

LIFE: Of course. The only thing as certain as death is that life is shared with others.

The same holds true for me and you.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

– If you can’t get enough of Life and Death, hang out with them more here.

– Life is precious, but it’s also ridiculously absurd.

Sources

Thomas Nagel – Death

Very Bad Wizards – Episode 133: Death and Dreams

Crash Course Video – Perspectives on Death – Crash Course Philosophy #17