Money Is the Megaphone of Identity

There was an extended period of time in my twenties when I didn’t have a job. For most of us, that’s not a big deal. We have our whole lives ahead of us to work, so taking a few months off to “find yourself” can be completely justifiable.

Well, let’s just say that wasn’t the case for me.

I spent sleepless nights scouring job postings for any company that might be interested in what little I had to offer. I smacked that “Upload Resume” button around like it was my arch nemesis, but made sure to carefully upload the proper file format before doing so.

My days consisted of nothing but napping, eating, uploading, and submitting. To put it mildly, I was in a state of panic to find some sort of work.

Some might have viewed this obsessive job search as an impressive character trait. It may have masqueraded as a signal of ambition, an indicator that I was a guy that had his priorities straight.

The truth, however, was far from that. I wasn’t driven by some magnificent search for purpose, or the nagging desire to provide value to society. I was driven by something far less chivalrous:

My intense, terrifying fear of being homeless.

For the longest time, this fear is what drove my panicked desire to find stable, well-paying work (regardless of how pointless it was). I thought that as long as I could save some money with each paycheck, I wouldn’t have to sleep in the streets if something went awry.

Some of you may understand this fear, while others may view it as deeply irrational. I know people from wealthy backgrounds who have this fear, and people raised on welfare that don’t. My family didn’t have much money growing up, but that doesn’t quite justify the existence of this strain of fright.

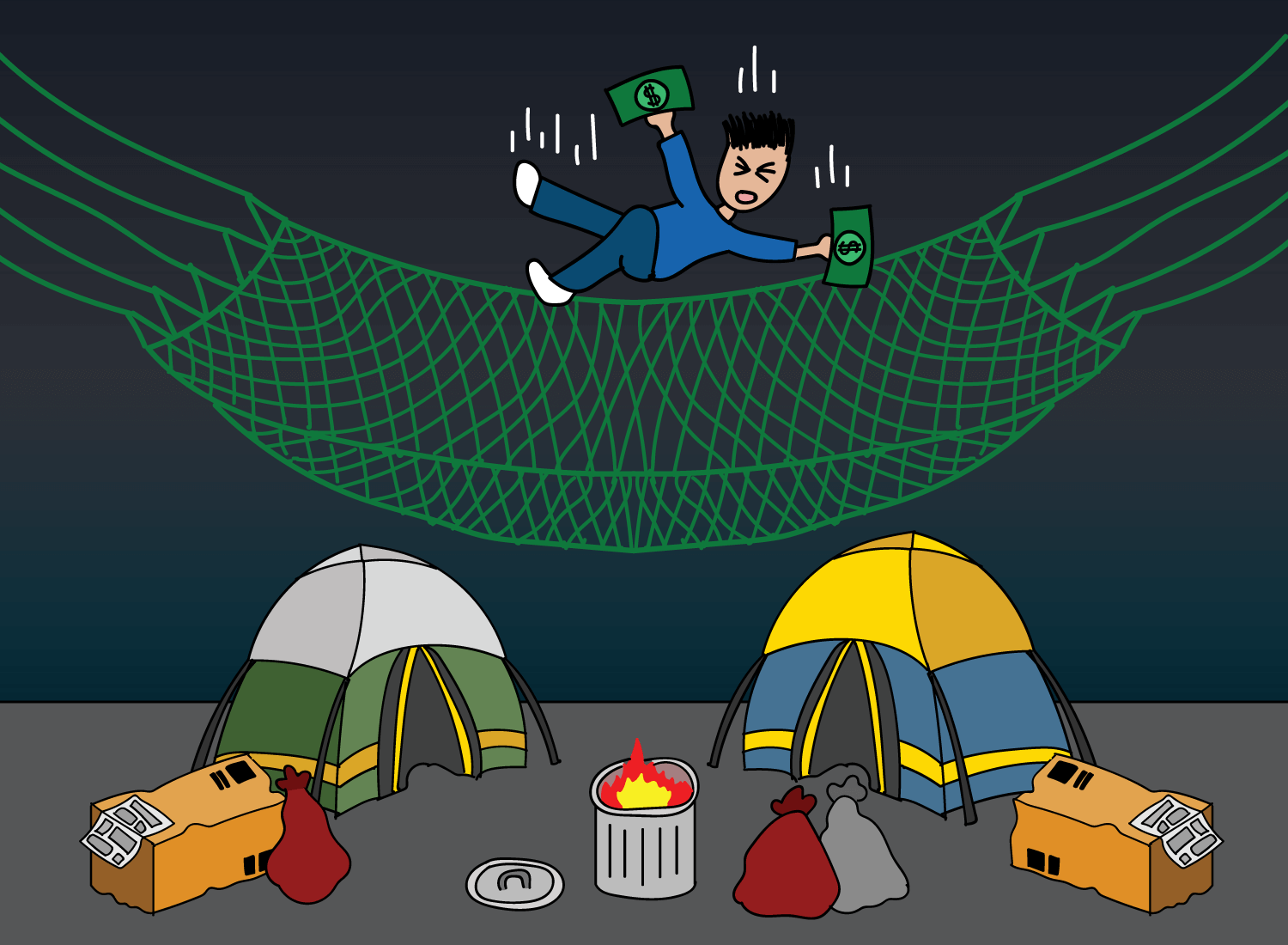

Regardless of its origin, this fear was very much alive in me throughout my twenties, and it framed my perspective of money. Instead of viewing money as a generator of wealth, I saw it as an immediate safety net that (barely) kept me away from living on freeway on-ramps. The more of it I had, the more relief and distance it gave me from the streets.

Well, many years have passed since then, and fortunately, I no longer have this fear.1 However, that doesn’t mean that I no longer think about money. It’s the greatest story humanity has ever subscribed to, so it will always be a central character in the theater of everyday life. What has changed isn’t money itself, but the way in which it colors the way I view the world.

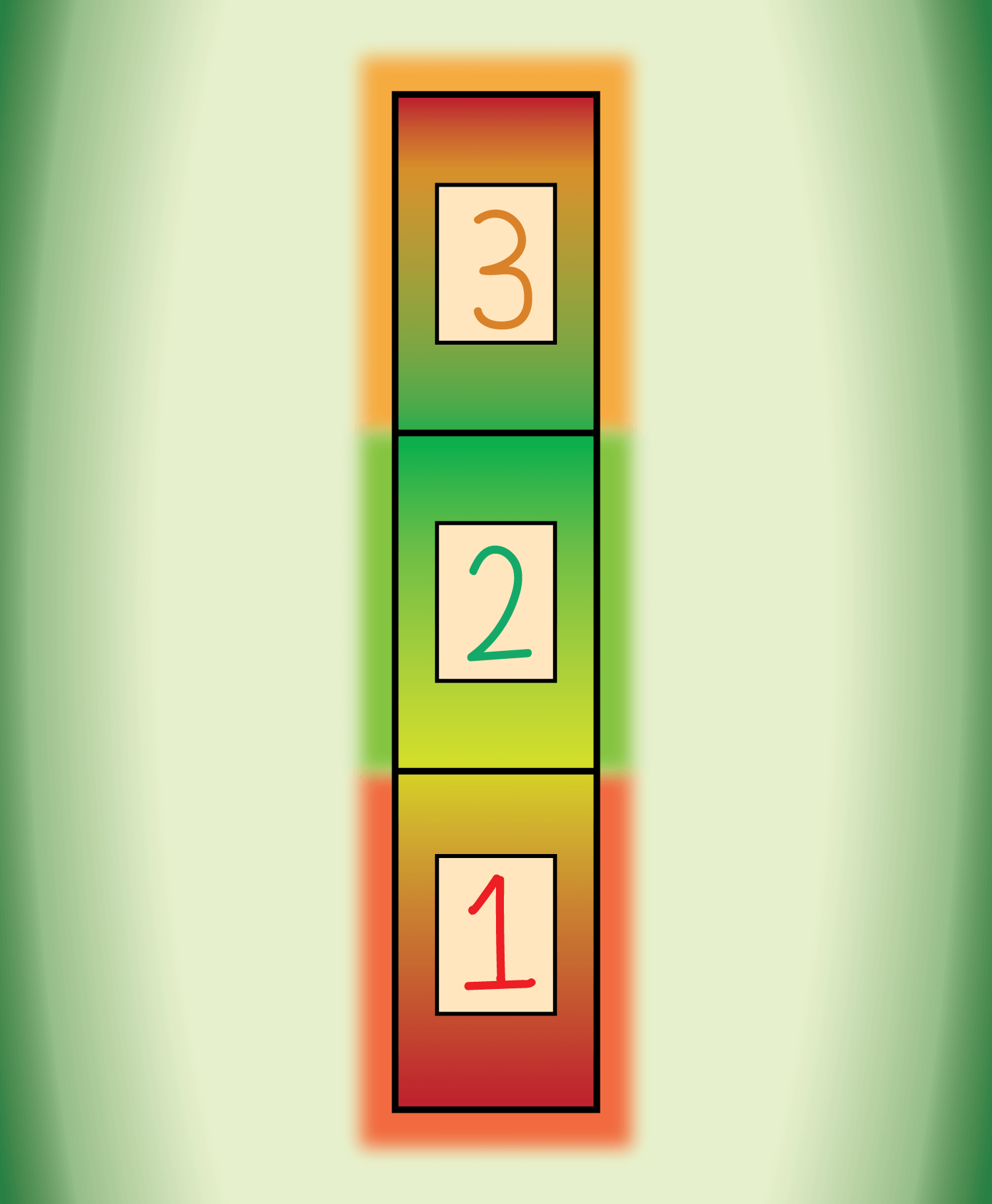

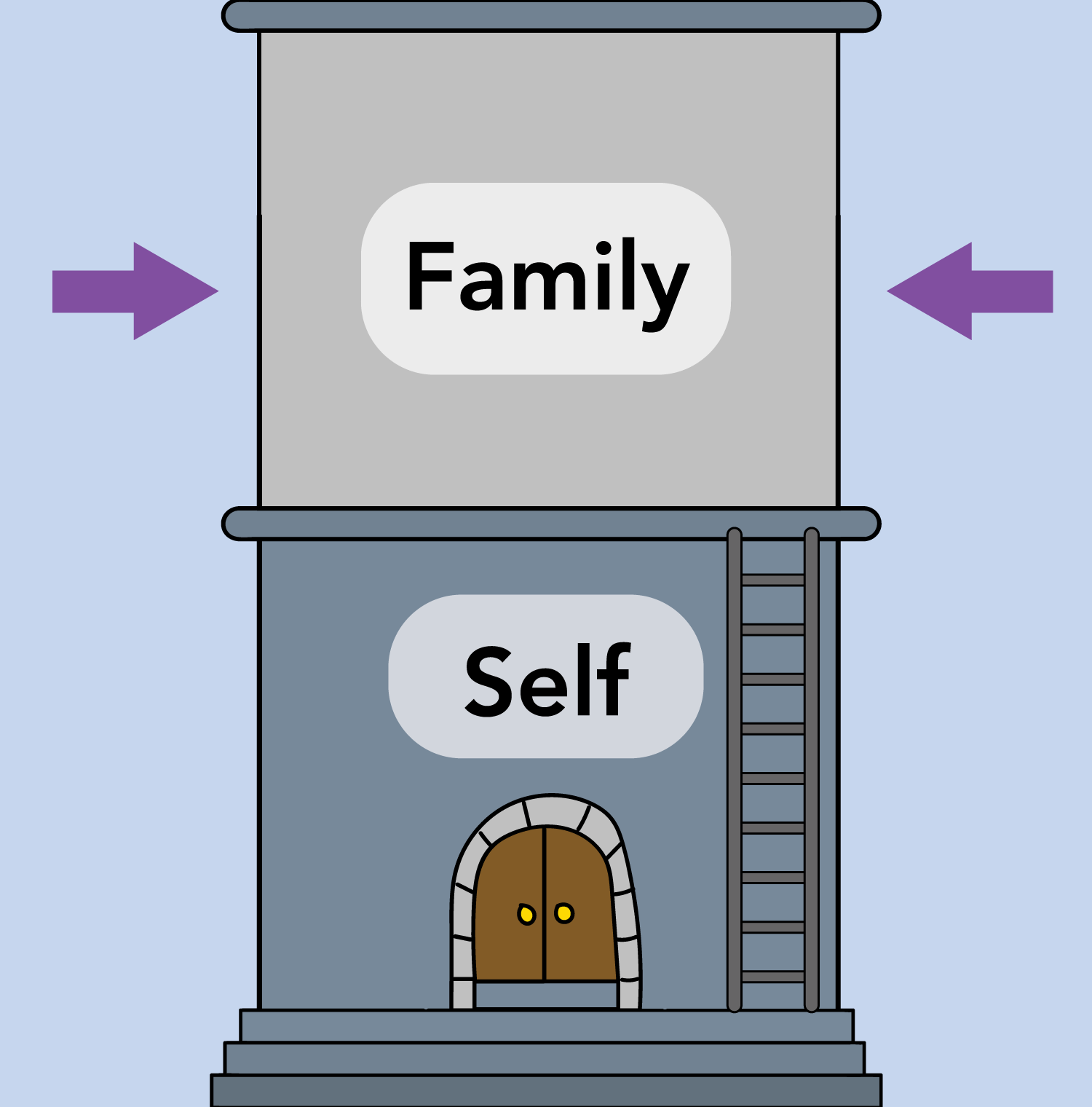

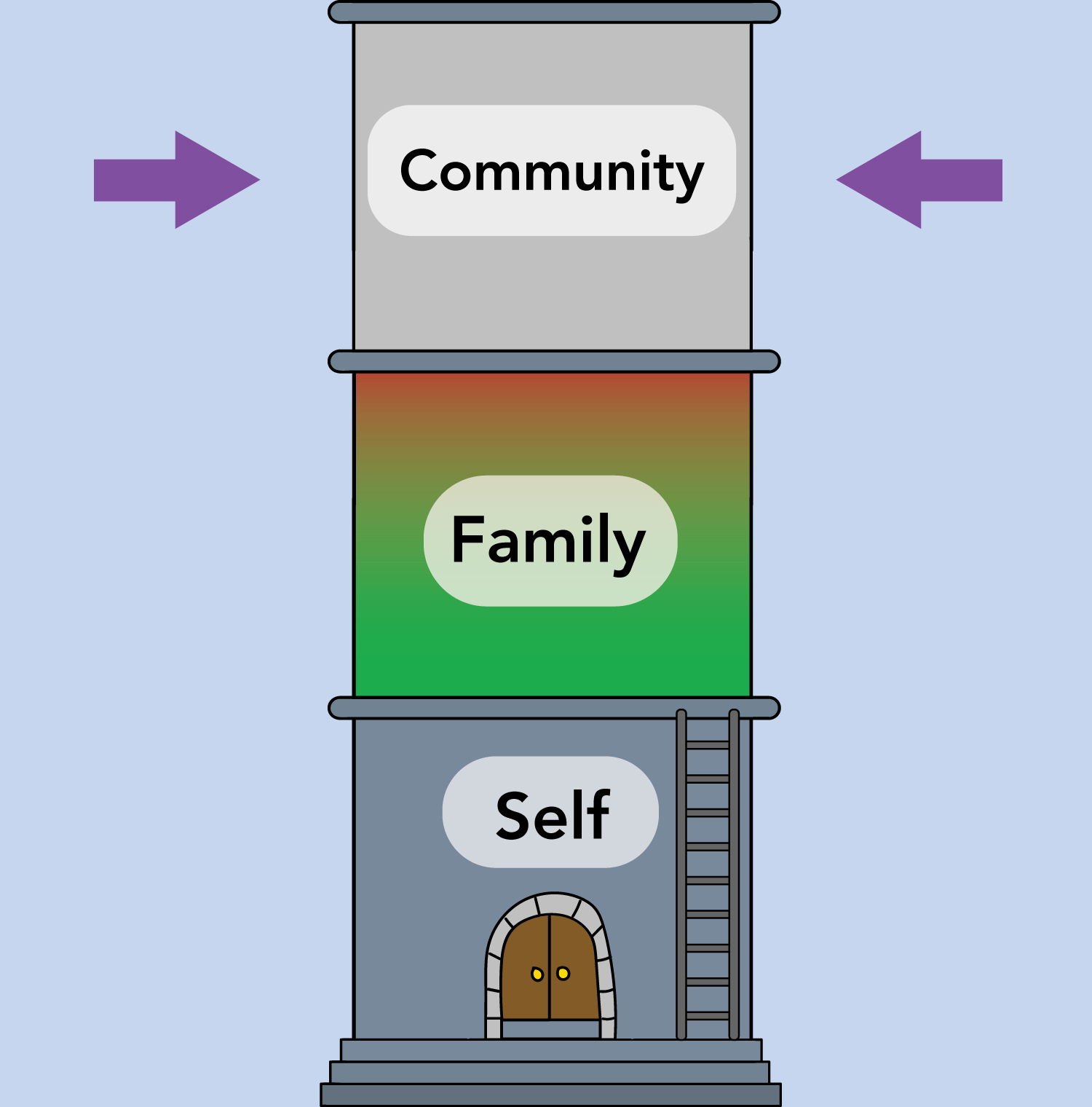

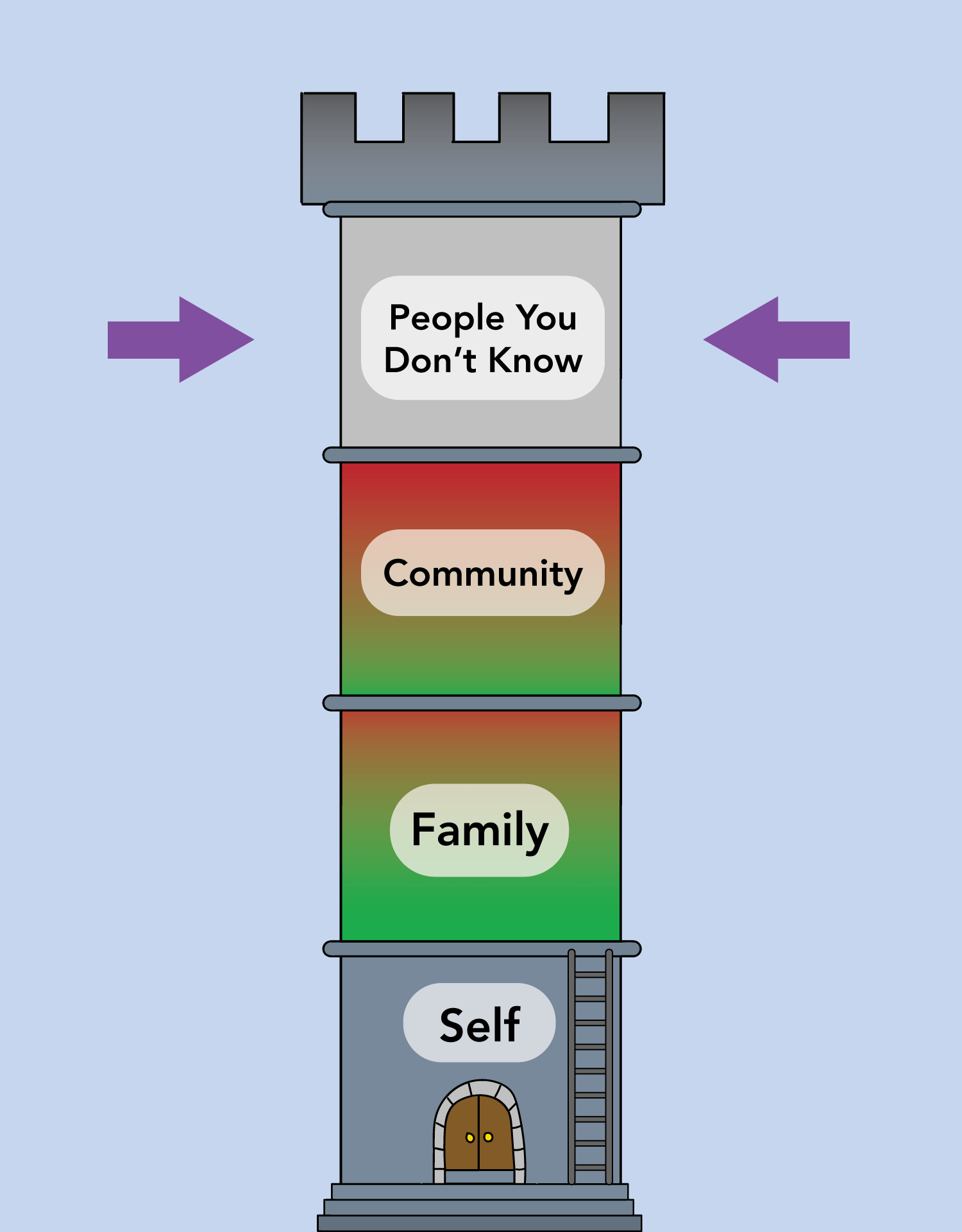

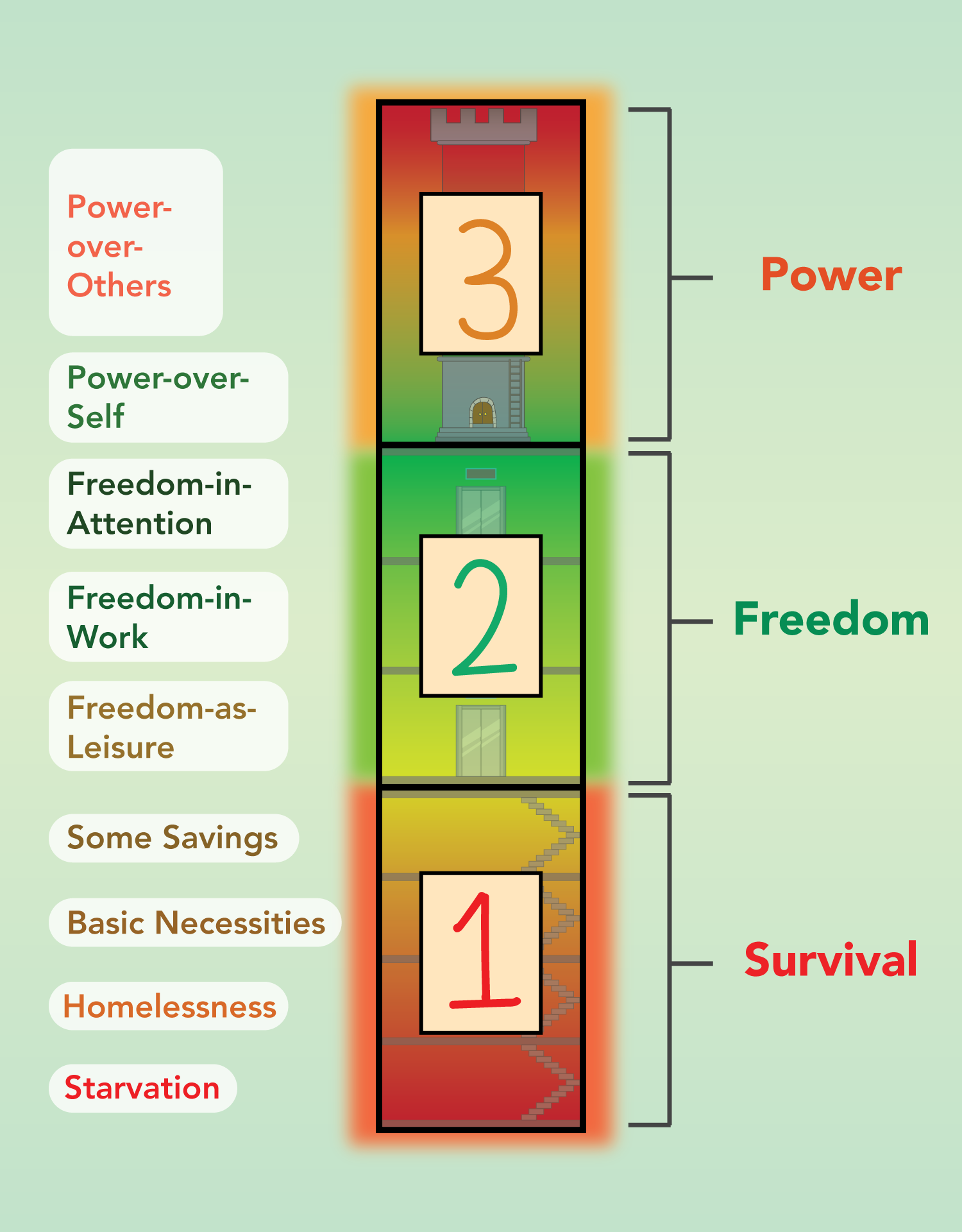

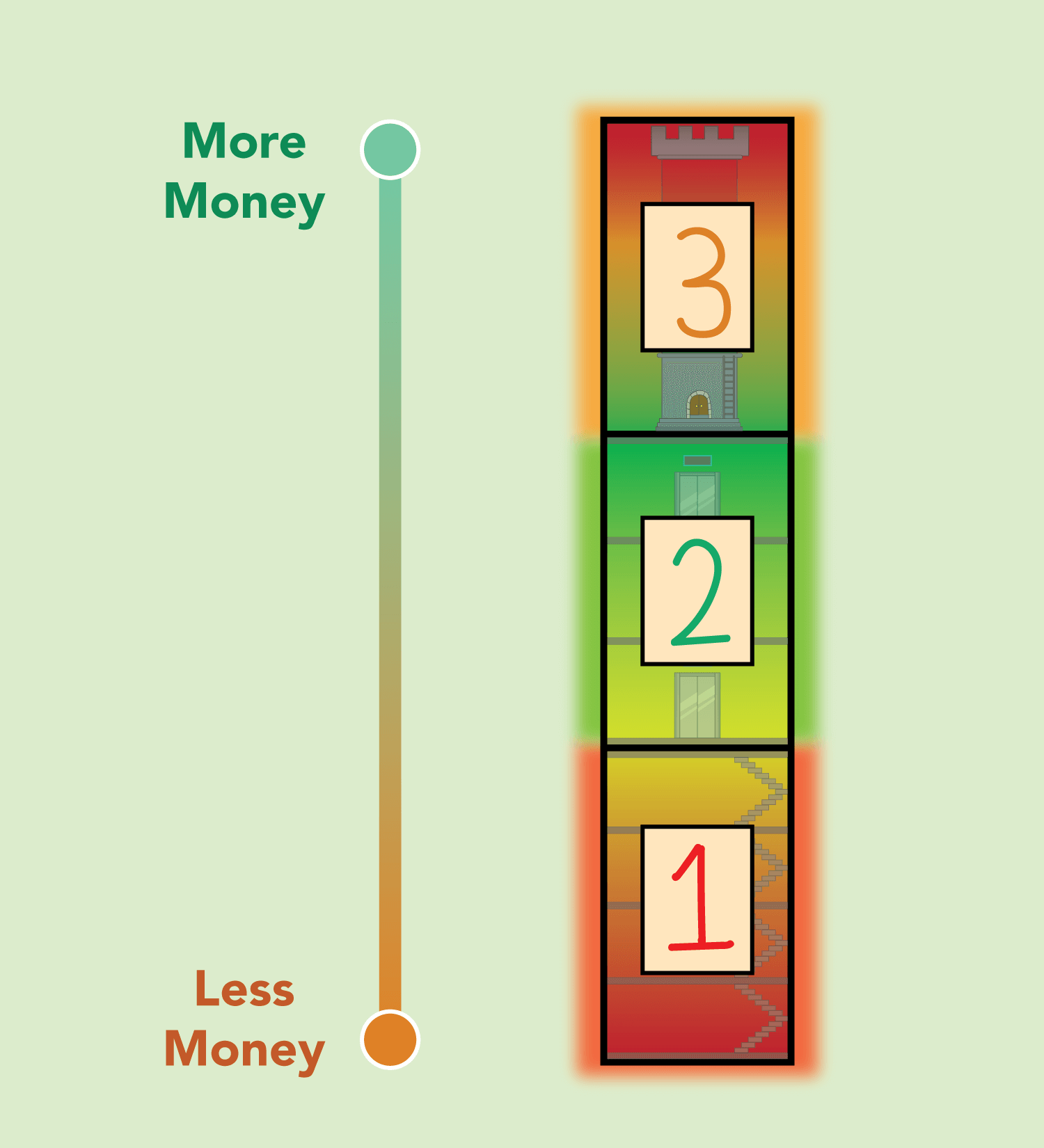

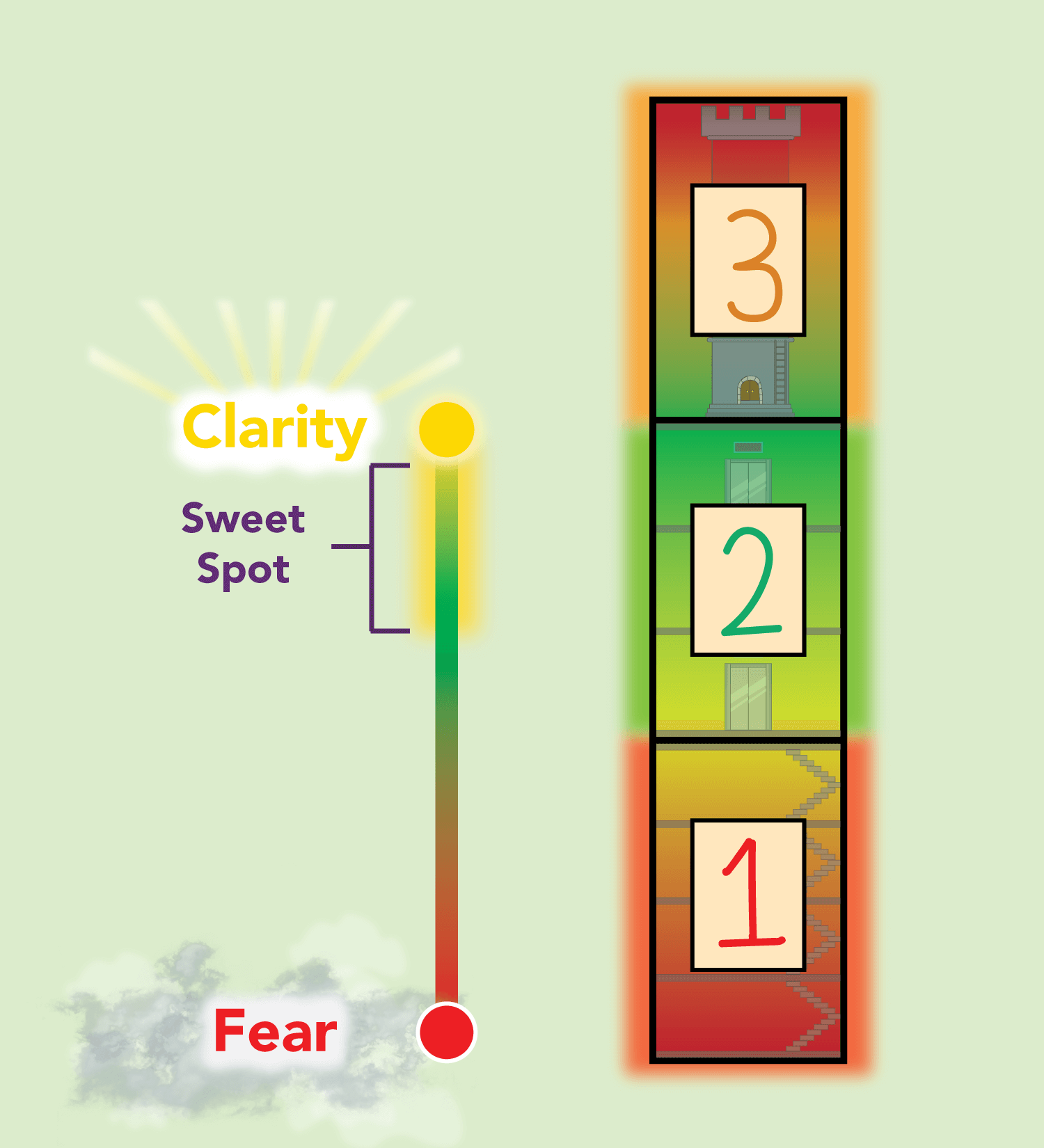

Life is almost always a framing problem, and wealth is no exception to this. To say that money is complicated is a cliche worthy of a thousand eye rolls, but when it comes to our ongoing relationship with it, I find that it’s quite simple to explain and distill. At any given moment, our journey falls along a vertical spectrum with three main phases:

This is what I call The Money Spectrum, and it represents the wide variety of views we have about the almighty dollar/euro/whatever throughout our lives. Money can be a difficult thing to talk about because it invokes a blend of weird emotions, and this amorphous slushie of feelings can be hard to express through the crude tool of language.

The purpose of the Money Spectrum is to take this formless slushie and build it into a concrete model that we can all understand. The first step to solving a problem is to articulate it clearly, and that’s what this spectrum is here to do.

Each of the three phases represent a specific purpose money has for us, with Phase 1 being the ground level of this journey up the tower. We will go into what each of these three phases are soon, but before we do, keep in mind that this is a spectrum, meaning that we will find ourselves sliding along the scale at any time.

It’s entirely possible that someone will be 100% immersed in Phase 1, but it’s more likely that they will be closer to Phase 1 than Phase 2, and will share characteristics of both areas. This is an important distinction that we will make later on in this post, but for now, remember that our relationship with things are rarely absolutes, and money is no exception to this rule.

Let’s begin our journey up the Money Spectrum with this question: when you take a look at your bank account balance, what do you feel?

Well, if you’re a part of the 28% of Americans that have no emergency savings whatsoever, the answer to that question will likely be a combination of fear and anxiety. When the sole purpose of money is to provide for the basic necessities of life, then your relationship with it will be a shaky one. Scarcity creates fragility, and it is this situation that opens the doors to Phase #1.

Phase #1: Survival

One might say that we all share some space in this part of the spectrum. Ultimately, all the necessities of life require payment of some kind: the food we put in our mouths, the clothes we walk around in, the roof over our heads, etc. Without money we wouldn’t have any of these things, so it’s fair to say that it is a requisite of survival for all of us, right?

Well, not quite.

While it’s true that money is required to have these basic necessities, that doesn’t mean that we all fear the loss of these necessities equally. A low-income household and an upper middle-class family may both rent property, but the former may worry incessantly about next month’s payment, while the latter may not. Both understand the importance of money, but have different ideas of how their survival could be impacted by the lack of it.

The difficult thing about the word “survival” is how subjective it tends to be, as humans are more reactive to loss than to gain. If a billionaire experienced a sudden reversal in fortune and couldn’t afford his ten-bedroom house anymore, it’s quite possible that he’d say his very survival was being threatened.

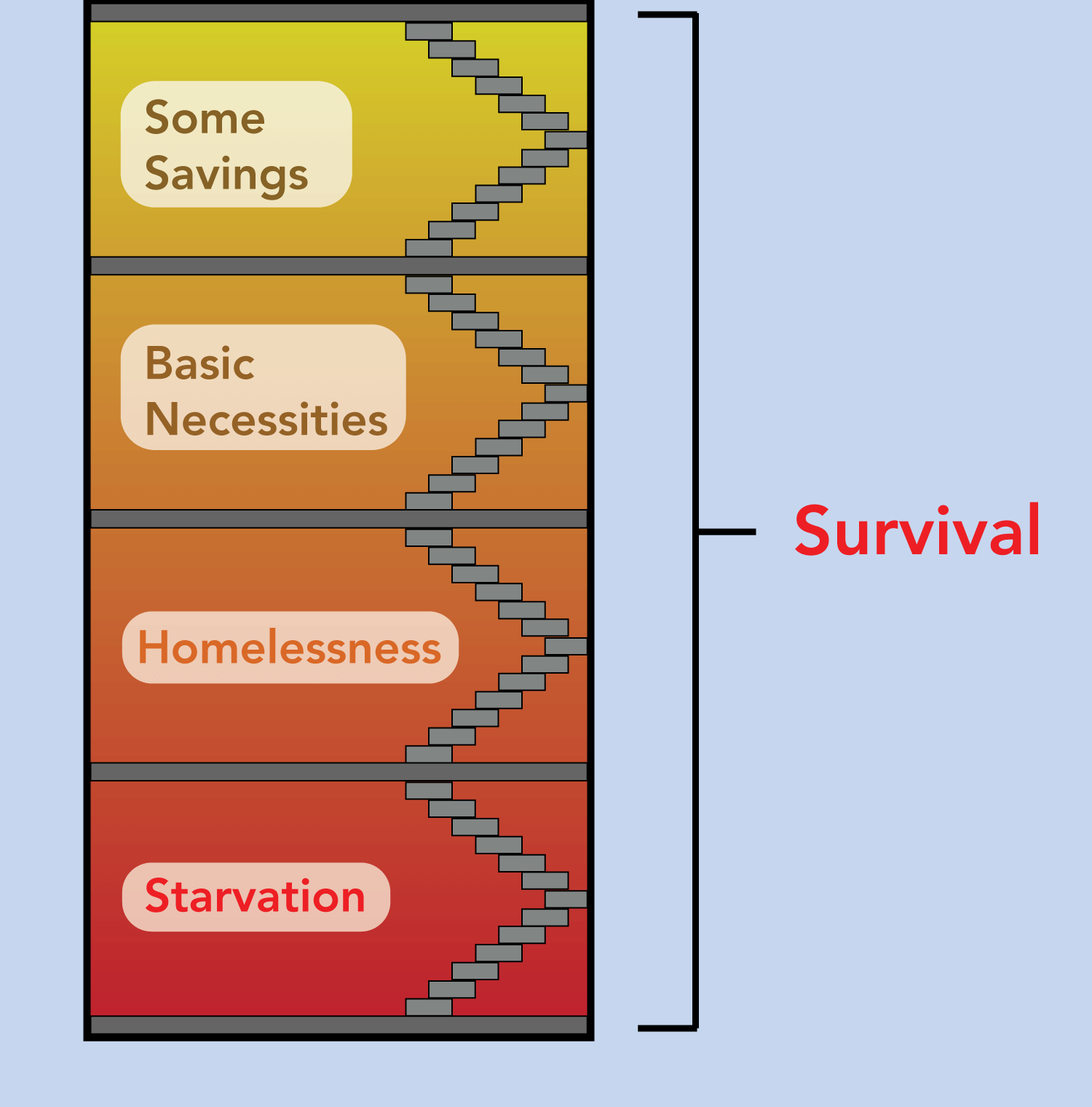

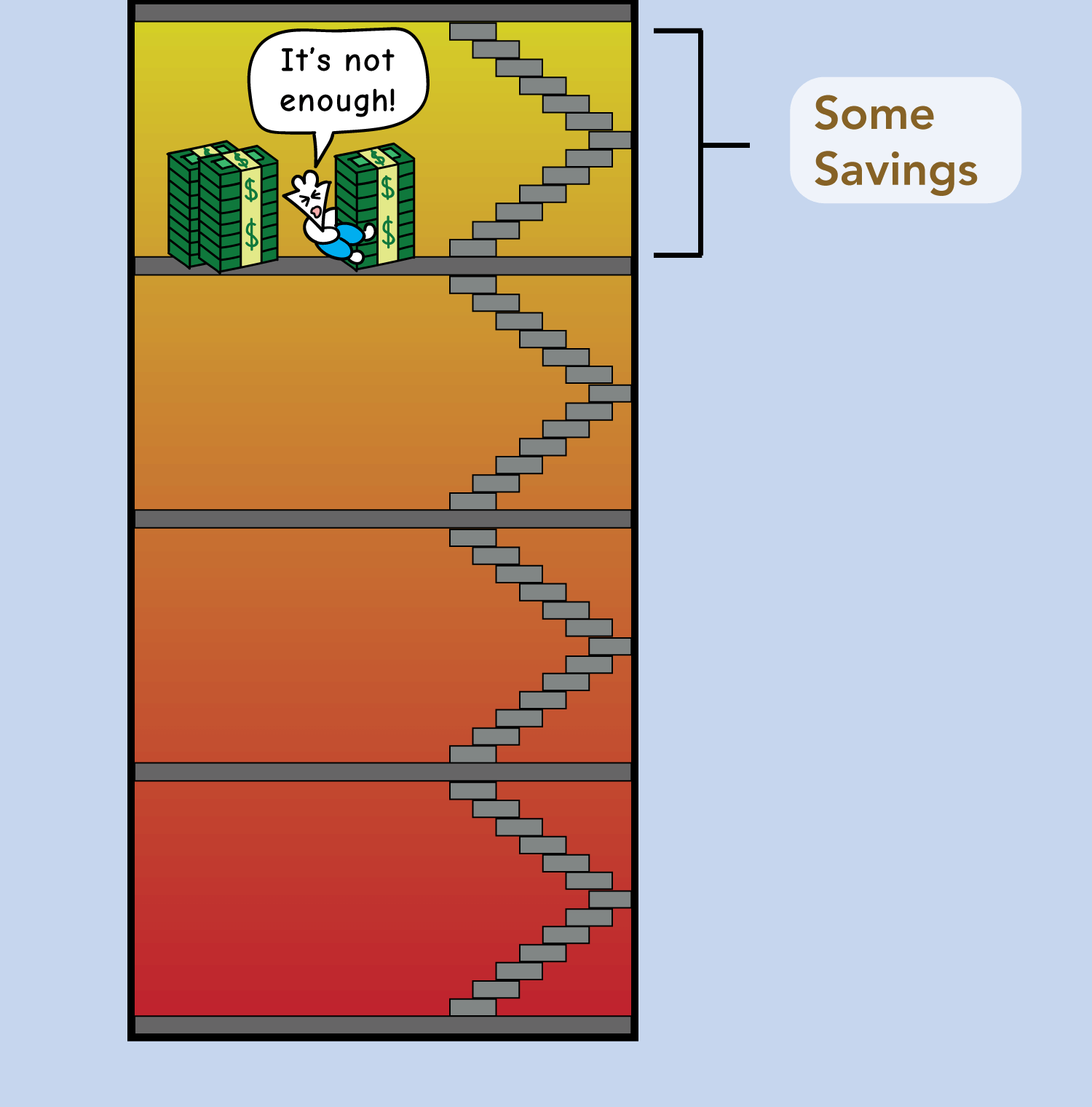

To remove this fog of subjectivity, let’s zoom in on the Survival part of the spectrum and break it down. When I use the word “survival” in this post, I’m simply referring to one’s ability to exist and to have one’s health. In the illustration below, I’ve separated the section out into its smaller constituents, with the level of poverty increasing the lower you go.

At the lowest level, you have no money or access to food, and you are literally starving to death. This is more likely a function of national/civic infrastructure than an individual’s lack of money, as this is quite rare in any first-world country. However, it is still largely a function of having no fiscal resources, and this is the worst place one can find themselves in as a result of that.

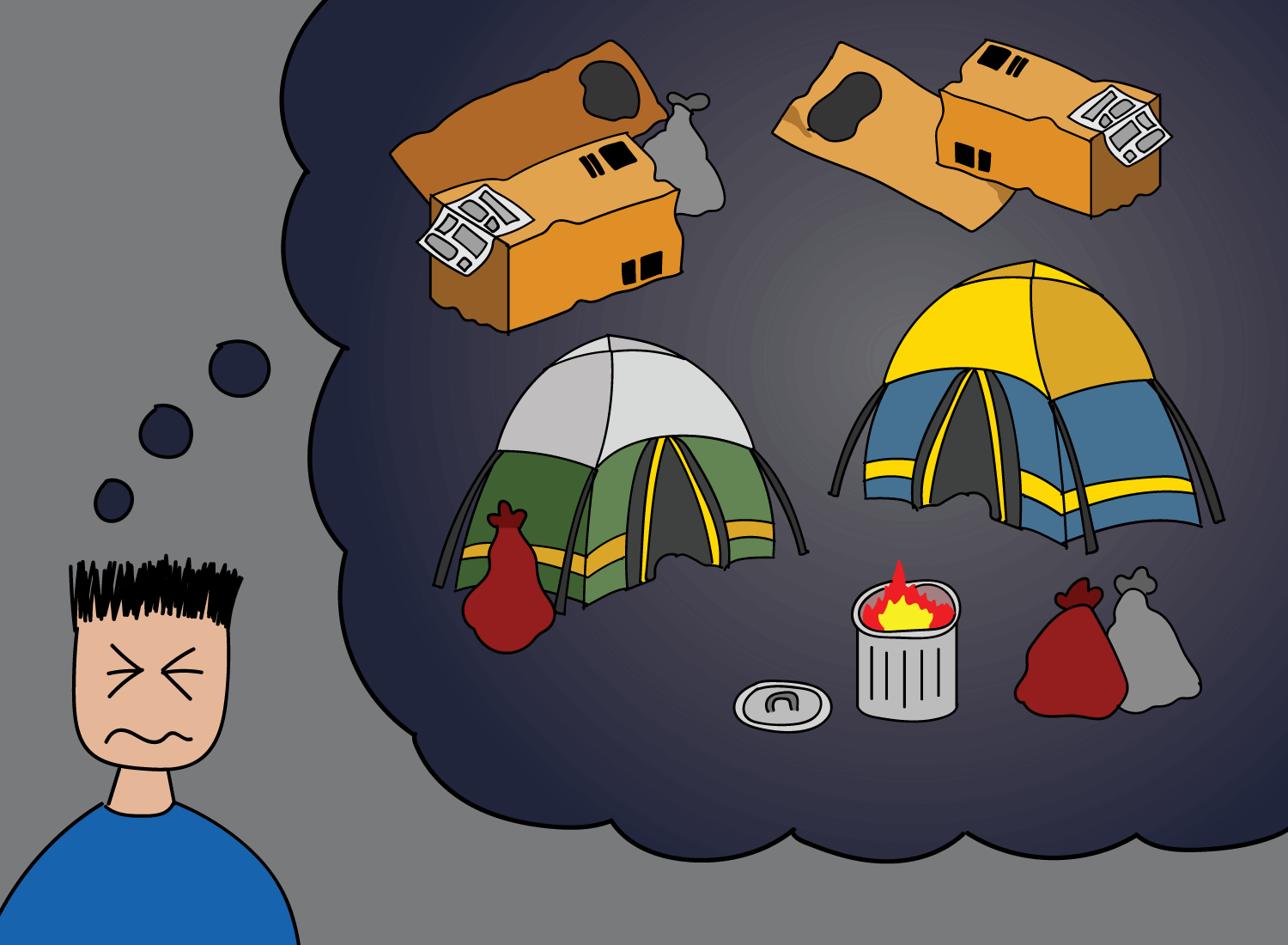

A step up would be the lack of shelter, or homelessness. This is where one’s fears regarding survival can start feeling real, despite the fact that they are probably nowhere near it (my own fear was a good example of this). This likely happens because most of us are vividly familiar with the problem of homelessness, and have grown up seeing real-life evidence of it everywhere.

I have clear childhood memories of my parents interacting with the homeless, and you probably do as well. Homelessness is an ever-present window into the difficulties of the human condition, and it reminds you of what can be possible when things go wrong. When we think about our survival being threatened, this familiar sight is where the mind can point to, regardless of how distant that place actually is.

The next few steps up the spectrum have to do with one’s idea of survival once they have their basic necessities (food/water, shelter, and clothing). Survival is no longer a relentless exercise in acquiring these necessities, but more so a strong commitment in maintaining them. And of course, the fuel that keeps the resource engine running is money.

In order to sustain the health of oneself and one’s family, a consistent stream of income is needed, and this generally comes in the form of paid employment. Keep in mind that toward the upper-end of the Survival phase, you are no longer fighting for existence; you are fighting for preservation. You want the flow of money to be predictable, something you can count on every few weeks to sustain the level of basic resources you need.

A job provides this sense of security, and when you view money as a means for survival, holding this job is all that matters. It doesn’t matter how much you hate your job or how terrible the working conditions may be; as long as the number of hours you work result in a predictable deposit amount, you’ll succumb to it.

But if this pattern continues and time runs in your favor, there’s a point in which the lines between the Survival phase and Phase #2 (which I’ll reveal shortly) start getting blurry.

At what point does your job provide you with enough money to feel a sense of security? Is it when you’re no longer living paycheck-to-paycheck and you’re able to save some money each month? If that’s the case, what do your savings have to look like for you to feel a sense of relief? $2,000? $10,000? $30,000?

Toward the upper end of this phase, survival becomes more about your mindset and less about your reality. You are well past the place where you risk sleeping in the streets, but you may continue to operate under the belief that it could happen at any time. This traps you into a limited way of thinking, and paralyzes your potential for growth.

When you’re in a survival mindset, you will always feel like you’re barely holding onto what you have. Whether that’s $1,000 or $100,000, nothing you have can adequately push away the fears you have about sliding down the spectrum. This may be the result of parental conditioning, personal experience, or any number of reasons, but the longer you view money as a means for survival, the less willing you will be to take the risks required to lead a fulfilling life.

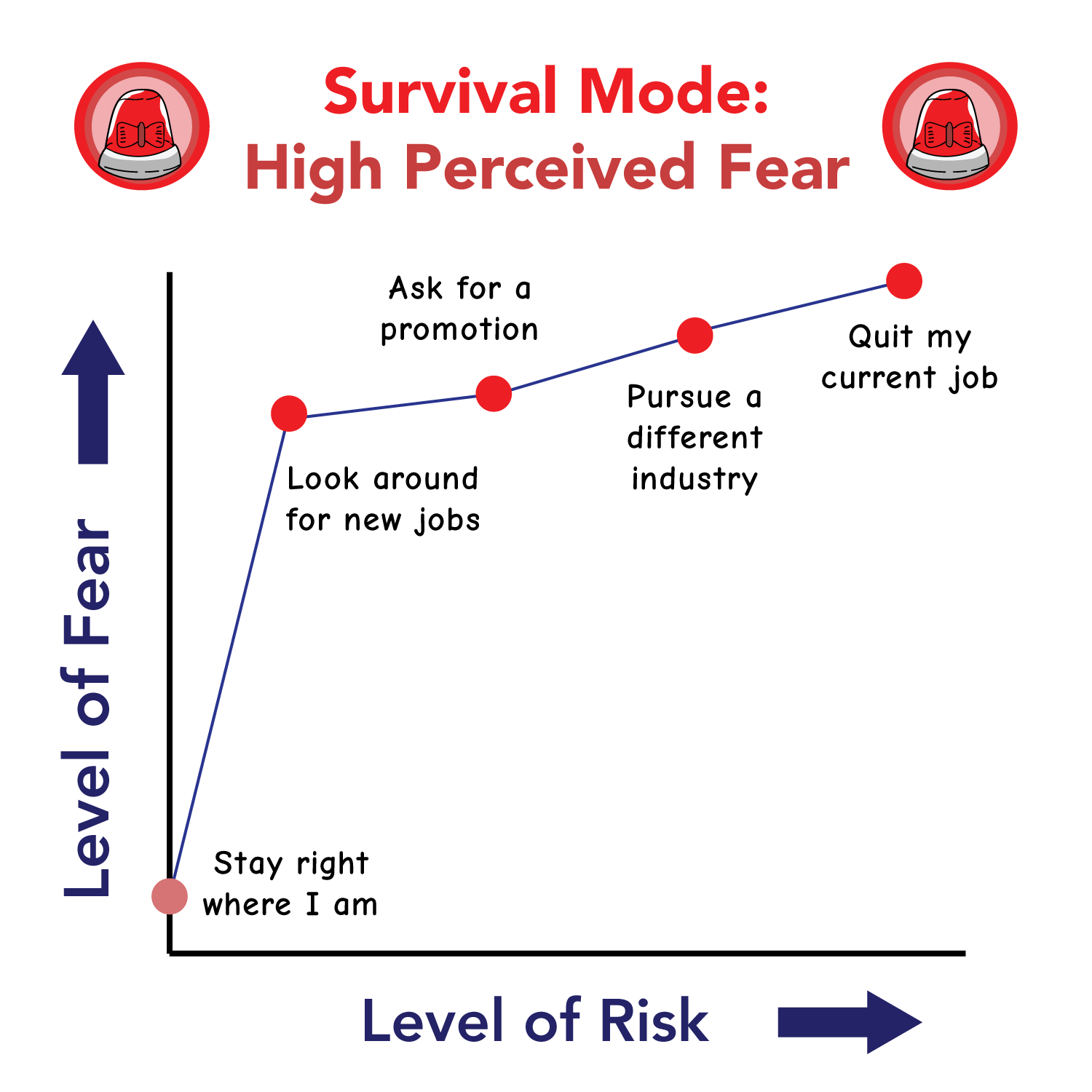

Risk is usually accompanied with the emotion of fear, and if you’re operating on survival mode, you will be scared to do anything uncertain, no matter how small that risk actually is:

With this level of consistent fear, you won’t do anything outside of your comfort zone. You’ll never ask for that promotion in fear of getting fired, you’ll never invest money in the stock market in fear of losing it, and you’ll never pursue something purposeful in fear of being penniless.

The most meaningful things in life come with some level of risk, and if you’re in survival mode, you won’t take them. The stakes will always seem too high, even if the downside to that risk is capped.

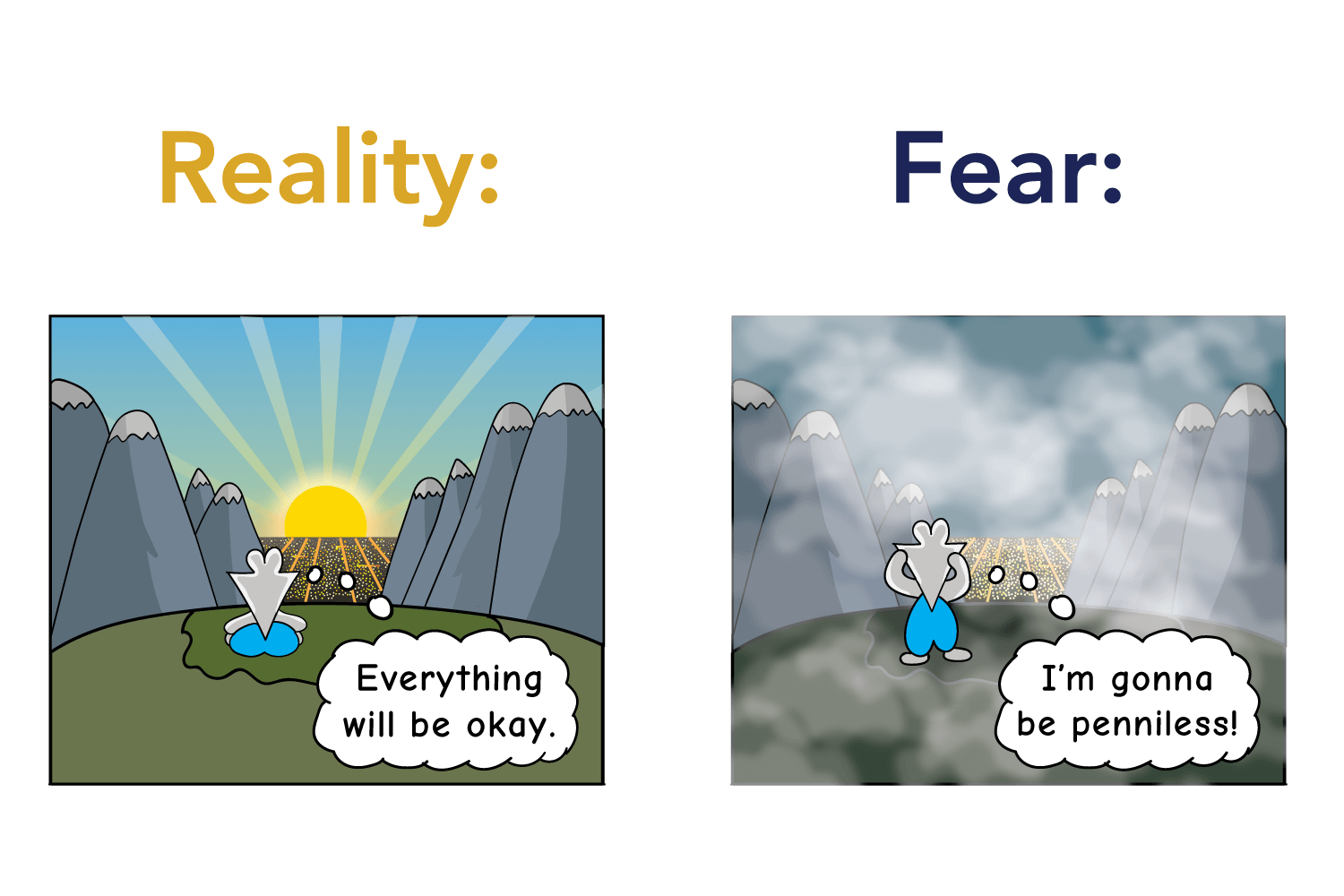

The key to shifting out of survival mode is to realize that you have enough. The word “enough” may evoke different feelings from different people, but I’m simply referring to the amount you require to have your basic necessities covered.

Do you have enough money to have a roof over your head? If you quit your job, will you really end up homeless, or will you be fine? Is your anxiety about money largely unfounded, considering you have your basic needs covered?

Survival mode is turned on when reality is clouded by the fog of fear. It turns a completely manageable situation into one that is overblown, and every small decision regarding money causes immense anxiety.

Removing this fog requires rationality, along with the understanding that everything will be okay. As long as you remain committed to your financial well-being, things have a funny way of working themselves out. If you lost your job, you will find another one. If you didn’t hit your savings goal, you’ll eventually get there. If you overspent your budget this month, you’ll make up for it in the next one.

Once you realize that money is a resource you own – and not the other way around – you will see money for what it really is: a tool that amplifies the values you already espouse.

In the next phase of the spectrum, money becomes a mechanism, rather than the end result. It is here where its value truly shines, as it enables you to live a life that coincides with purpose.

Phase #2: Freedom

I recall a conversation where a friend was telling me how much she hated her job. When I asked her why she was still working there, she begrudgingly replied, “Well, it provides a lifestyle that my family and I can enjoy. We can go on cool vacations together, see interesting places, and eat amazing meals. I guess that’s what makes it worth it.”

This is the first taste of money as a tool for freedom. When money is used to sustain a lifestyle rather than life itself, you have moved out of Survival and into this new territory.

One of the most common forms of freedom is leisure. Once you have your basic needs covered, leisure becomes the manner in which you express your tastes and preferences to yourself and others. Purchasing memorable experiences and delicious meals is not only pleasant, it also signals the things that are important to who you are.2

When you and your family are sitting on beach chairs in a faraway country, overlooking the oscillating waves of the sea, it can evoke feelings of the good life. It can make you feel like you’ve reached the pinnacle of freedom, and that everything you had to do in life was worth it for this moment.

But this is also where the problem lies.

The price of leisure can be high, and since life familiarizes us with its contents, we tend to want more of what we already have. If leisure is the way we express our freedom, we would be willing to do all kinds of tedious work to fund that form of expression.

This is the situation that my friend found herself in. She was putting up with mind-numbing, pointless work so it would give her the resources to fund the lifestyle choices that made life a little more pleasant.

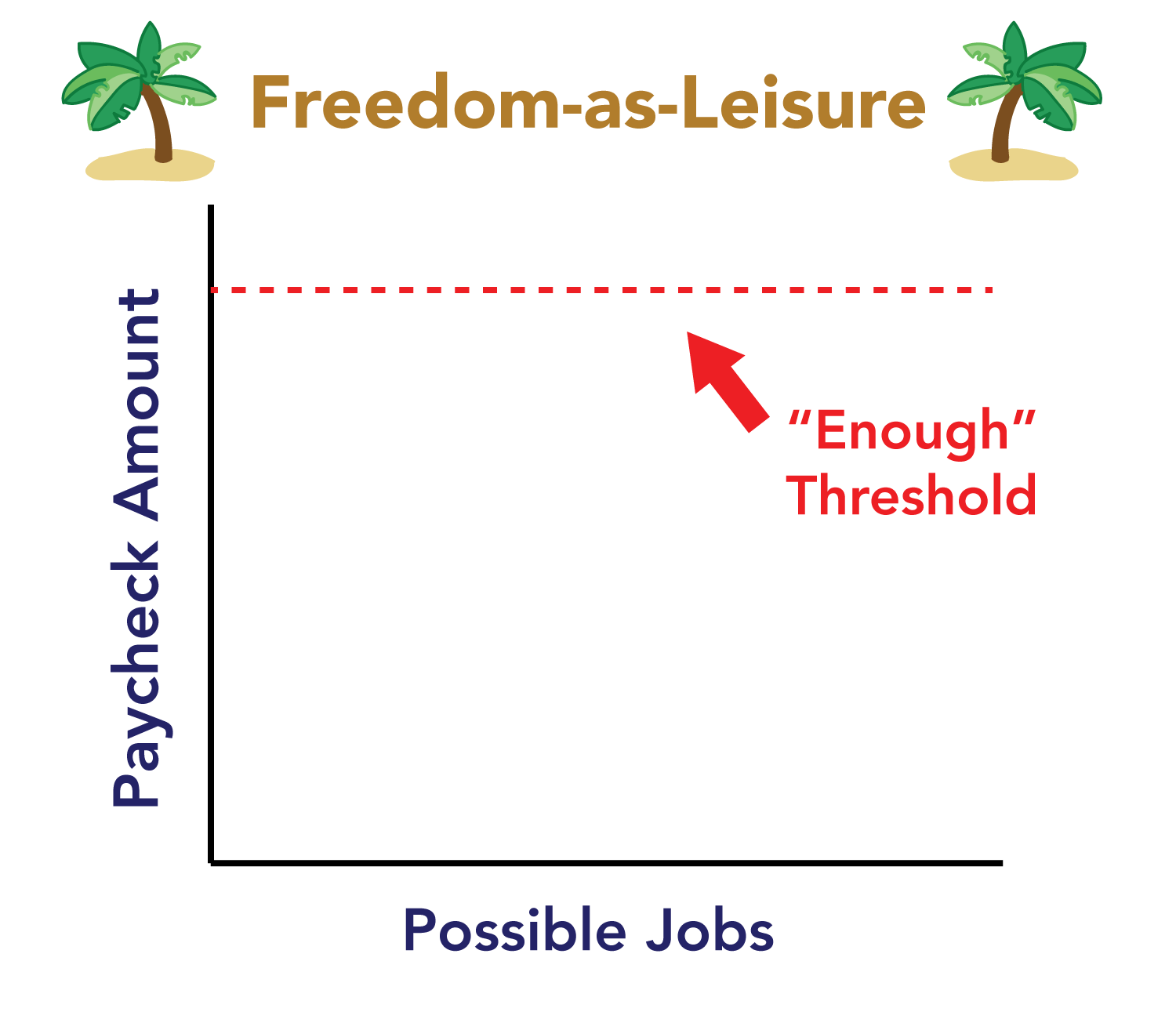

The problem with freedom-as-leisure is that it is fundamentally asymmetrical. You have to work significantly more hours for each hour of leisure you may gain, which means that if you hate your job, you have to accumulate a lot of misery before you can cash it in for freedom.

The sad reality is that many people don’t enjoy their jobs, nor do they learn much from them. If you combine this with the fact that we spend over a third of our lives working, you have a situation where money is the only reason you’re waking up each morning for a long, long time.

This is why these are the top results when you search “retirement” in Google Images:

For most people, retirement means they are finally free to do whatever they want without worrying about money. They could finally leave their jobs, travel around the world, and set their schedules so it fits their rhythm of life.

However, this is a low bar for freedom. Giving away thirty-plus years of your life to an indifferent career is like spending all your youth with a partner that you’d rather not be around. When you finally break free of that job or relationship, you’ll be left wondering what else you could have done with all that misspent energy.

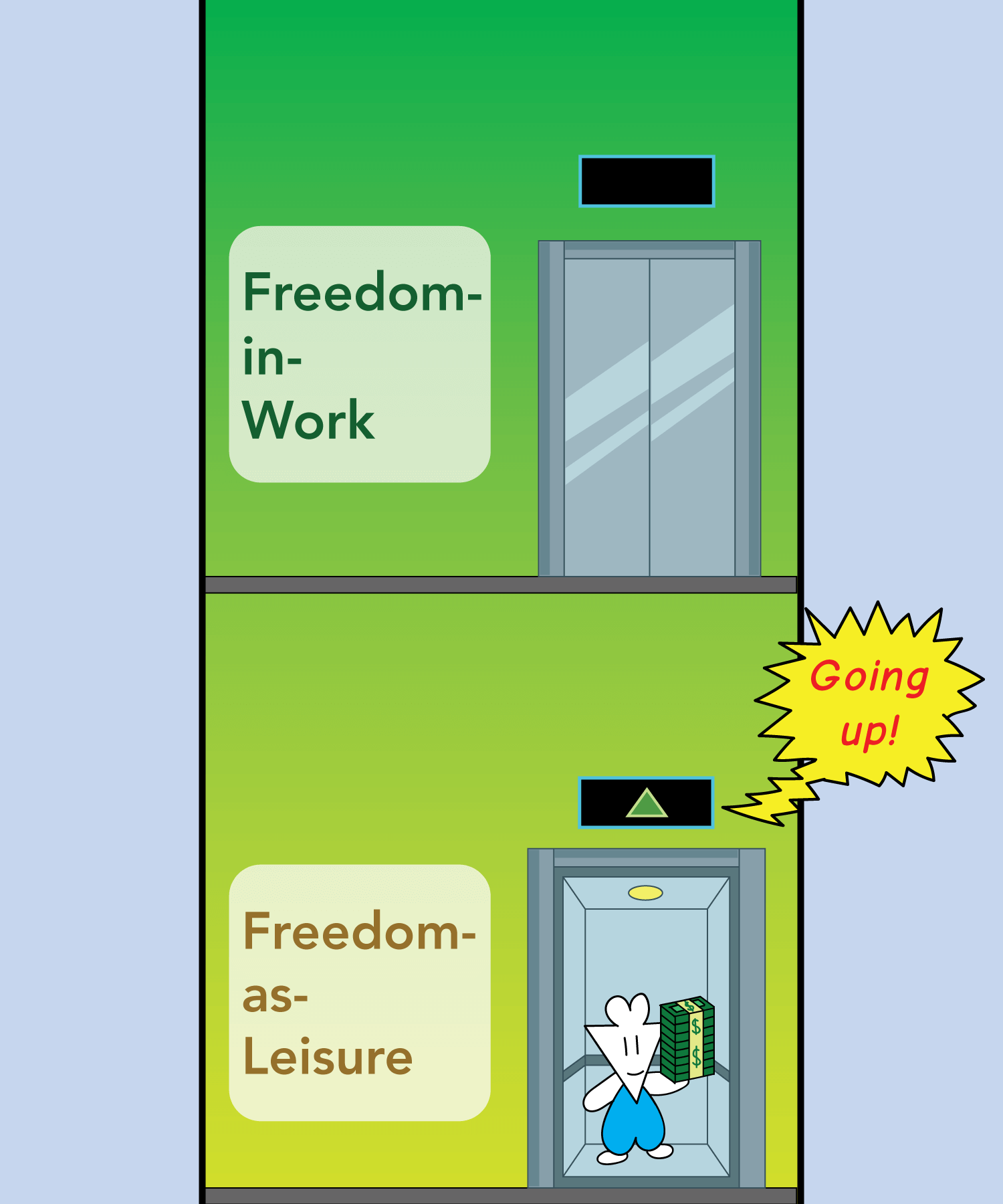

As long as money is the top priority for why you work, you will be trapped in the lowest part of the Freedom phase. To escape this trap, the way you view money needs a perspective shift:

Rather than using money as the ticket out of an unfulfilling career, use it as the ticket in to a fulfilling one.

The next point up the spectrum is the freedom money can buy as it relates to your work.

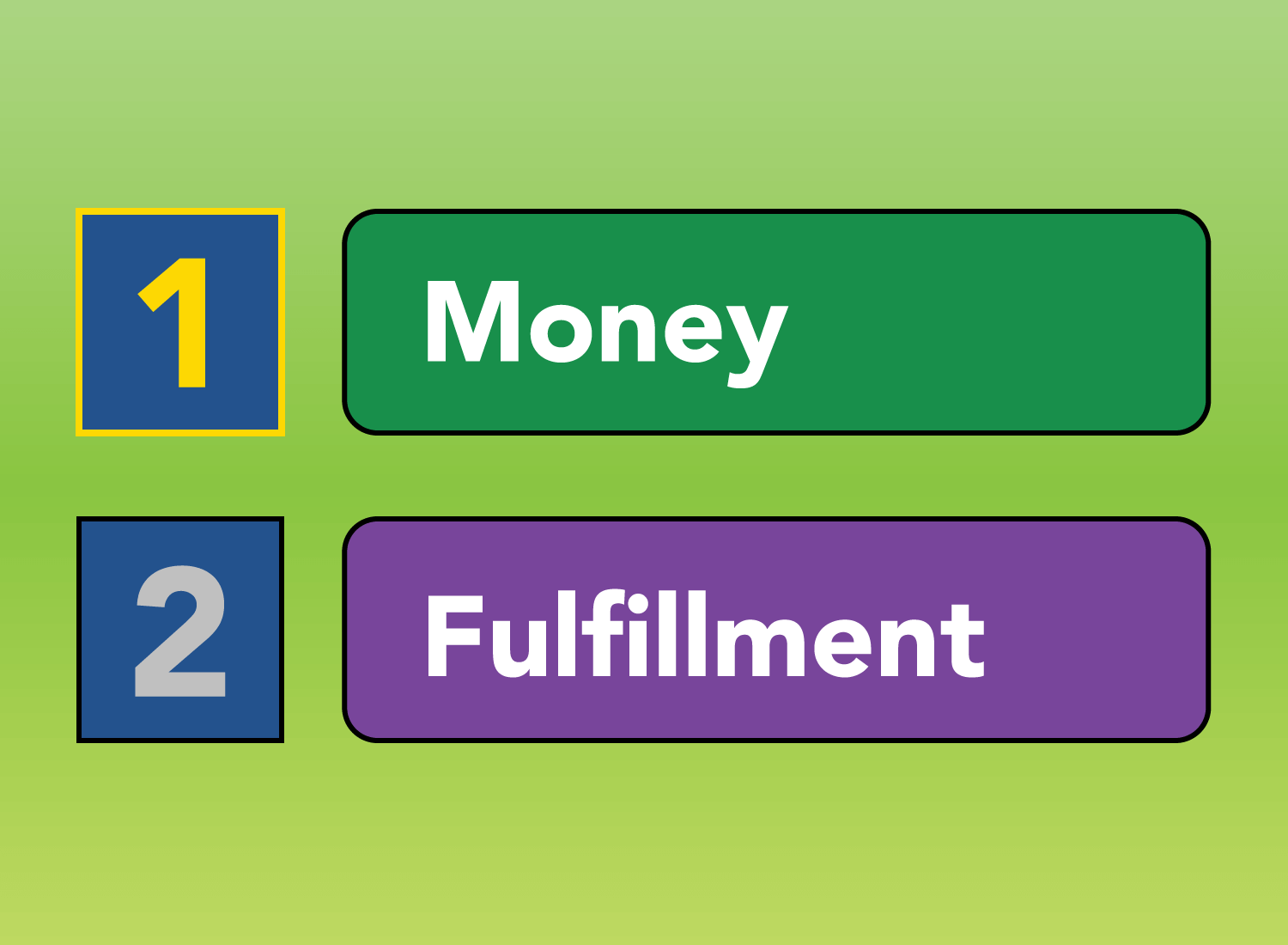

In the freedom-as-leisure (or traditional retirement) model, the rank-order of the reasons for work was this:

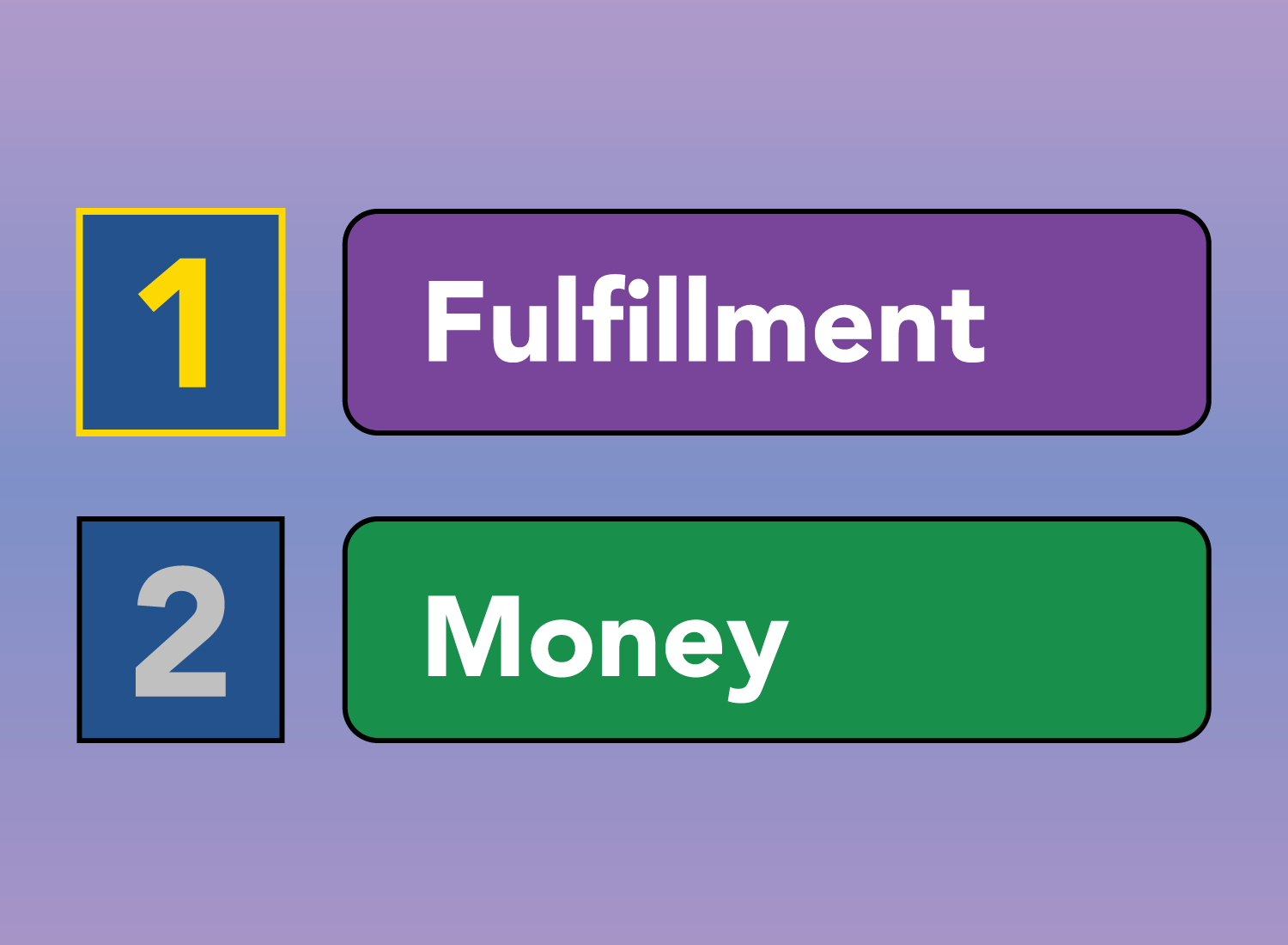

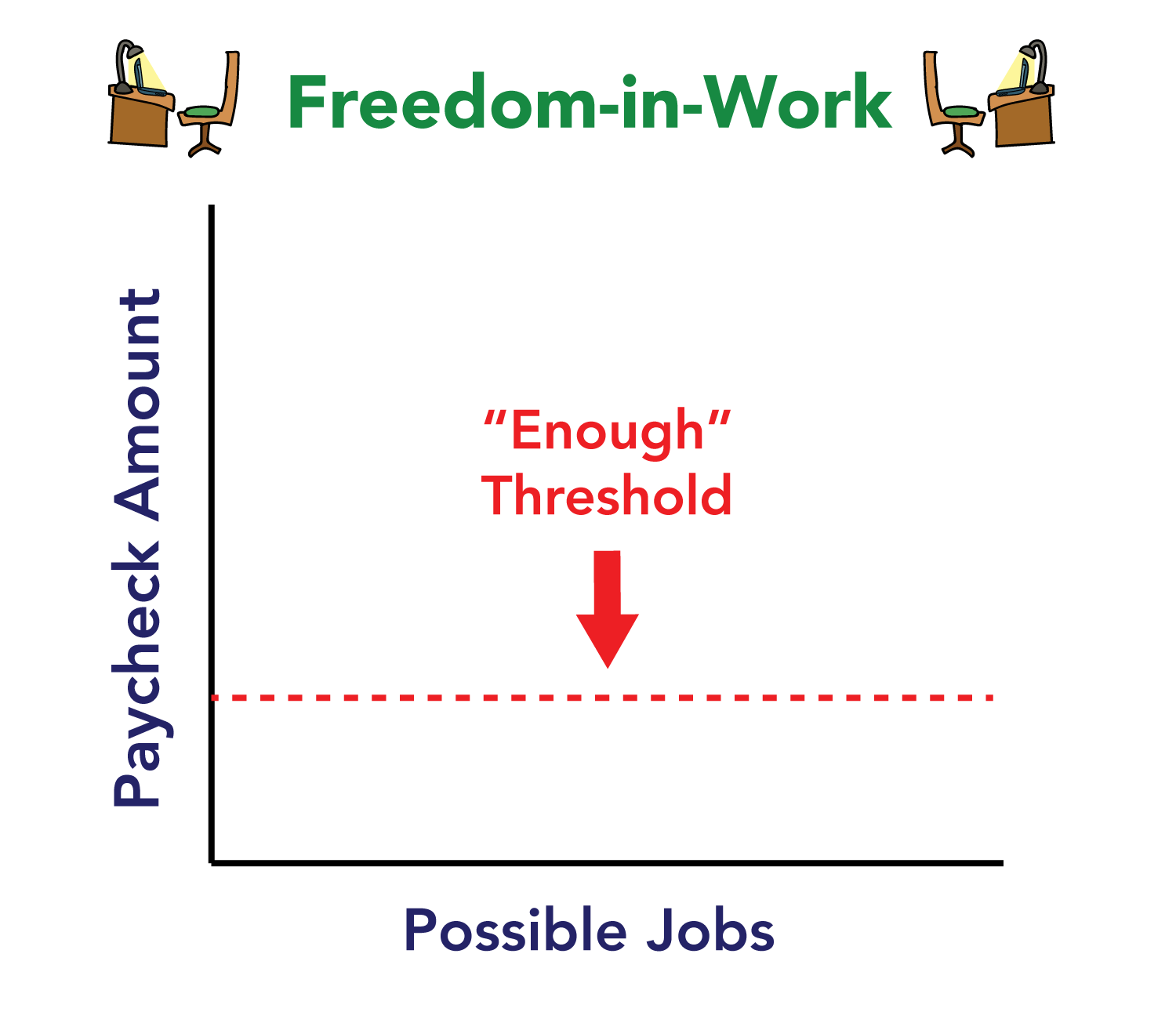

But in the freedom-in-work model, the order of priorities switches:

It’s still important to make money, but its purpose extends beyond its mere accumulation. Its primary purpose is to give you the freedom to work on the things you want to build.

This is where you realize that work isn’t about retirement; it’s about working on the things you’d do if money wasn’t even a factor. Whether you made $1,000 a month or $10,000, you’d continue working on the same projects, day in and day out. Not because they’re profitable, but because you enjoy the hard work it takes in building them.

Of course, the question here then becomes, “How much money do I need to buy this type of freedom?”

The answer will vary based on your circumstances (the biggest ones being where you live and if you have a family of your own), but it’s probably not as high as you would expect.

The first thing that the freedom-in-work model does is that it lowers the threshold of money you need to continue your work. When work in itself is fulfilling and worthwhile, you become more content with a minimal lifestyle.

This is because money no longer serves as a reliable signal of your worth and priorities. In the freedom-as-leisure model, the amount of money you made from your job was of utmost importance. If money was the only justification for your continued employment, that salary better be high enough to make your time worth it.

But in the freedom-in-work model, money is simply the fuel you need to keep you and your endeavor running. If you combine this with the zero marginal cost nature of the internet (especially for content creators), you don’t need much to live your day-to-day life. As long as your basic necessities are covered, you can continue working on the things you care about for a surprisingly long time.3

While this sounds liberating, I get that it can seem far-fetched. Untying money from your self-worth is a rather difficult thing to do. We’ve been conditioned to view money as an indicator of success, and it is a status signal that is recognized anywhere in the world. Wealth drives perceptions, both of ourselves and others.

But ask yourself: how long will these societal norms control the way you live your life? What’s so great about having money if you’re using it to live a life you’re expected to live, instead of one that makes sense for your unique abilities and perspectives?

Money is easily replicable, humans are not. There is no one out there that shares your same genetic makeup, let alone your life experiences. While a dollar is innumerable, you are – quite literally – one of one.

So don’t let something plentiful like money be the building blocks of your identity. Instead, allow it to amplify the authentic voice only you can have.

In the freedom phase, money is seen as a tool, an amplifier of the authenticity you embody. It is the resource that allows you to take care of yourself as you work on the problems you find worthwhile. You don’t need a lot to keep going, you just need enough.

Although the mindset of “enough” sounds great, I understand that it can be difficult. After all, the hardest part of this journey may be the stress that comes from monitoring the balances in your bank account. If you’re pursuing this endeavor as a side hustle, you may have some leeway here, but if it’s your full-time thing, the fact that “enough” may be slightly out-of-reach can induce anxiety.

The key here is to remain (1) diligent, (2) patient, and (3) rational.

Diligence refers to your work ethic. There are no shortcuts to this. No amount of wishful thinking can substitute the necessity of hard work.

Patience refers to your resilience. The benefits of compounding always come later, and patience is what allows you to drive the long, bumpy road necessary to get there.

Rationality refers to your mindset. Will you helplessly slide down into Survival mode, or will you understand that you’re actually exercising freedom, spending your time solving the problems you want to work on? Can you be rational about your situation, and understand that you will be okay?

Combine these three tenets with the mindset of “enough,” and eventually you will find yourself in an interesting situation. A while ago, nobody seemed to care about what you were working on, but now, a niche of people have grown to love your work. Some of them even pay you for your services, your products, or whatever you have to offer. Slowly but surely, you’re able to expand your money tool belt a few notches.

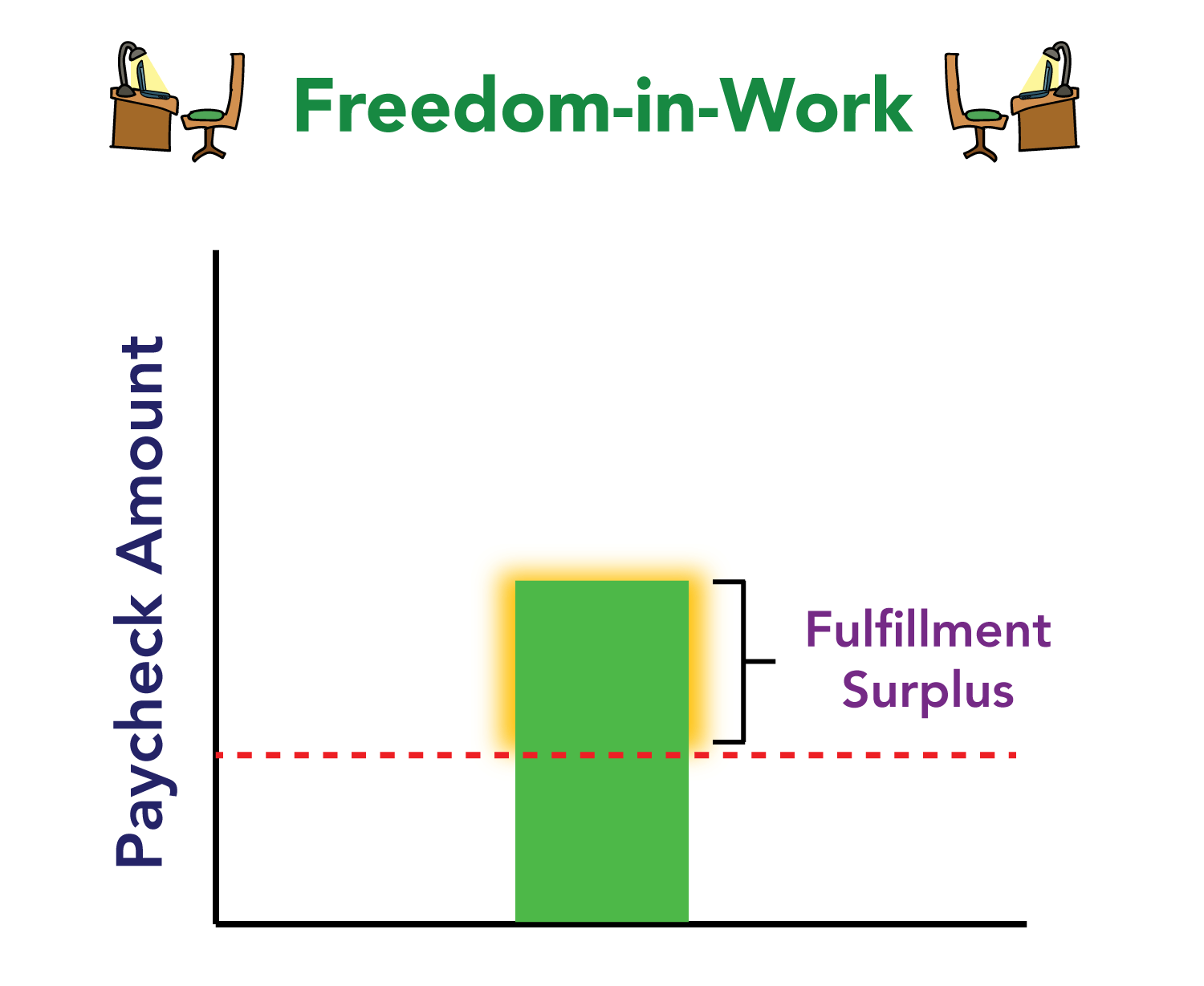

When the income you generate from your endeavor begins to exceed the threshold of costs to keep things going, you get what I call the Fulfillment Surplus.

The Fulfillment Surplus is the best kind of money one can have. Not only do you have more than you need, you’ve earned it doing something that you would have done for free. Better yet, the reverse is also true: you would’ve worked on this endeavor even if you had all the money in the world.

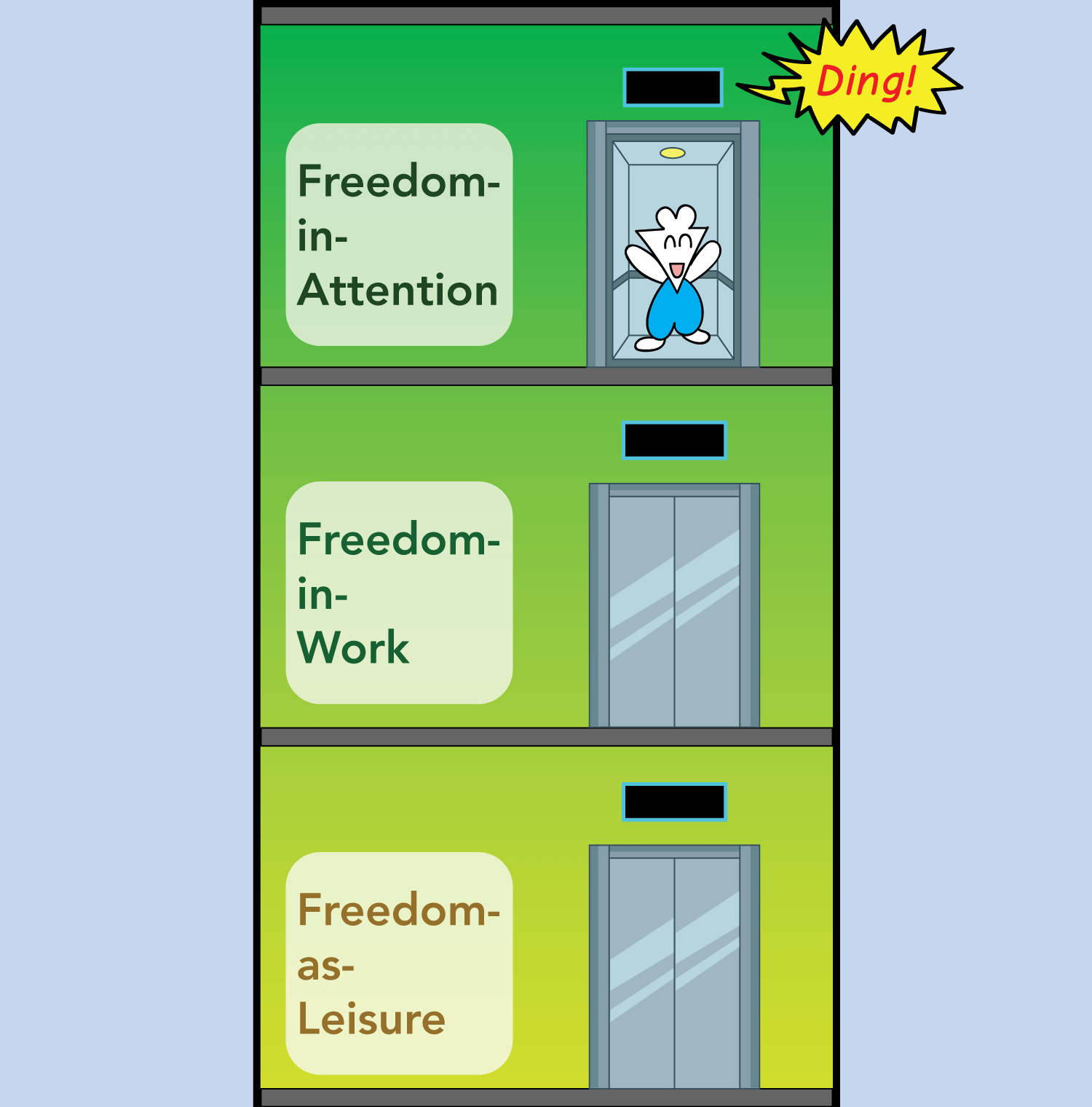

But perhaps the best part of the Fulfillment Surplus is that it frees your attention away from money. The hardest part about doing meaningful work isn’t the work itself, but the stress that can result from frequently checking your bank account balances. The Fulfillment Surplus is the ticket that takes you away from here and into the highest end of the Freedom phase:

Freedom-in-attention.

When we think of financial freedom, we tend to picture a super rich person in this situation:

And when we think of someone’s who not financially free, we picture an average person in this scenario:

However, if the super rich guy spends all his energy thinking about how much money he has and how he’s going to sustain this lifestyle, then he is not wealthy:

But if the average person doesn’t ruminate about money because he knows he has everything he needs, then he is wealthy:

Financial freedom isn’t about money, it’s about attention. The less you have to think about money, the more free you actually are.

This is what the Fulfillment Surplus helps you realize. Once you get to the top of the Freedom phase, you are using money in a way that serves you. It is a tool that has enabled you to do the things you love, and has drifted out of focus when it has fulfilled that specific purpose. This is the sweetest spot in all of the Money Spectrum, and if we didn’t have any other aspirations or desires, then we’d be wise to stay here for a long time.

However, it’s inevitable that our relationship with money will extend past the domain of the self. If we have families, we will want to use money in a way that gives our children the best possible lives. If we are part of a community, we will want to use money in a way that allows our fellow members to thrive.

When it comes to the network of lives that are connected to ours, money can amplify these bonds dramatically… for better or for worse. It’s up to us to determine which direction it’ll go in, and this reflection takes us into the final phase of the Money Spectrum.

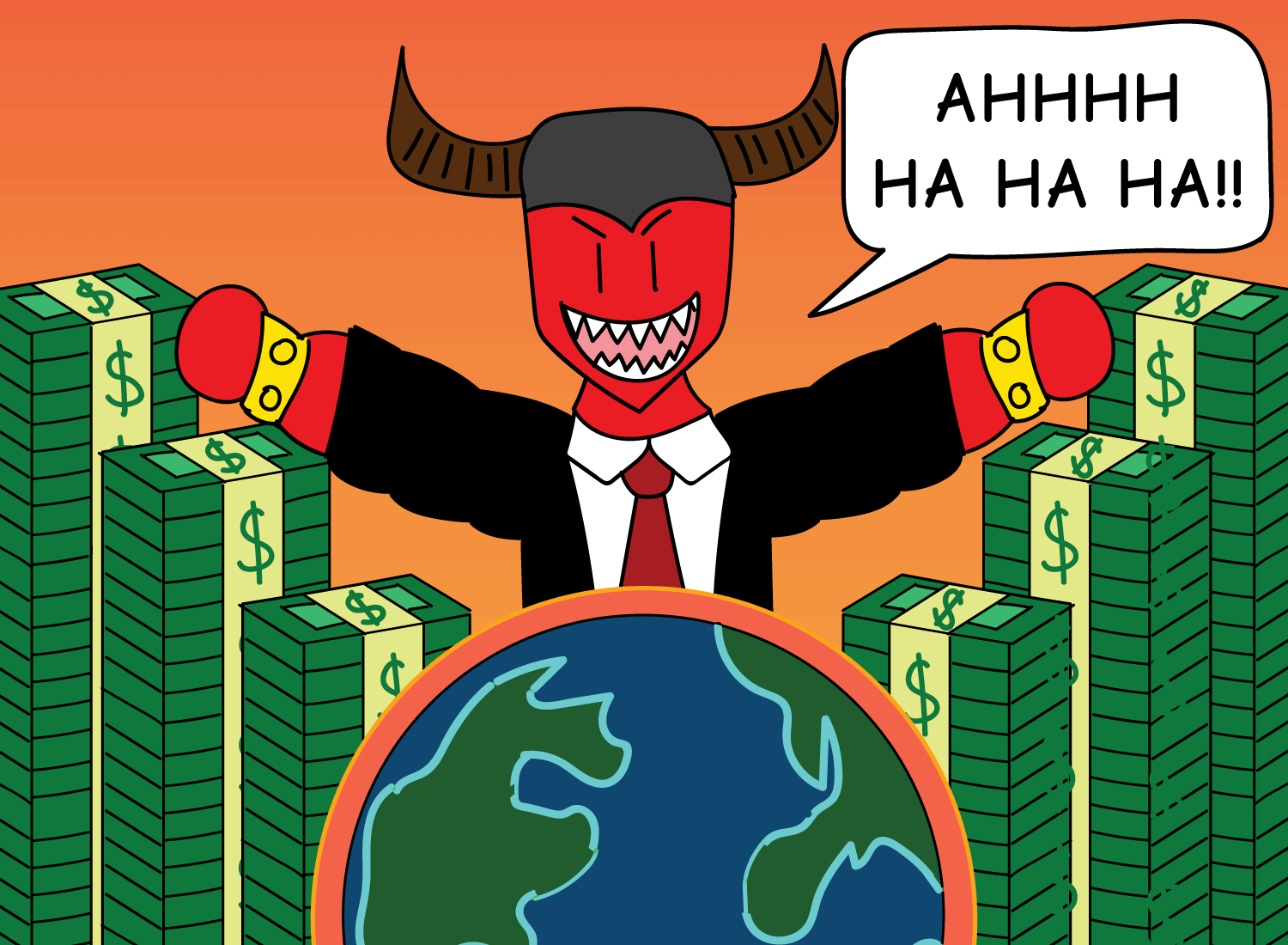

Phase #3: Power

When you think of the word “power,” an image like this probably comes to mind:

But let’s take a moment to see how our linguistic overlords at Oxford actually define the word.

1. the ability to do something or act in a particular way, especially as a faculty or quality.

2. the capacity or ability to direct or influence the behavior of others or the course of events.

These two definitions provide a good framework to understand power, but notice that there’s no value judgment in either of them.

Power in itself is neither good nor evil. We often conflate the outcome of one’s power with one’s possession of it, but we must remember that these are two wholly different things. If someone used power in a horrible way, that doesn’t mean power in itself is evil. It just means that a shitty person got their grubby hands on a value-neutral ball of influence, and exercised it with malice.

At its core, power is about two things:

[Definition #1] One’s ability to act freely, and

[Definition #2] One’s ability to influence the behavior of others.

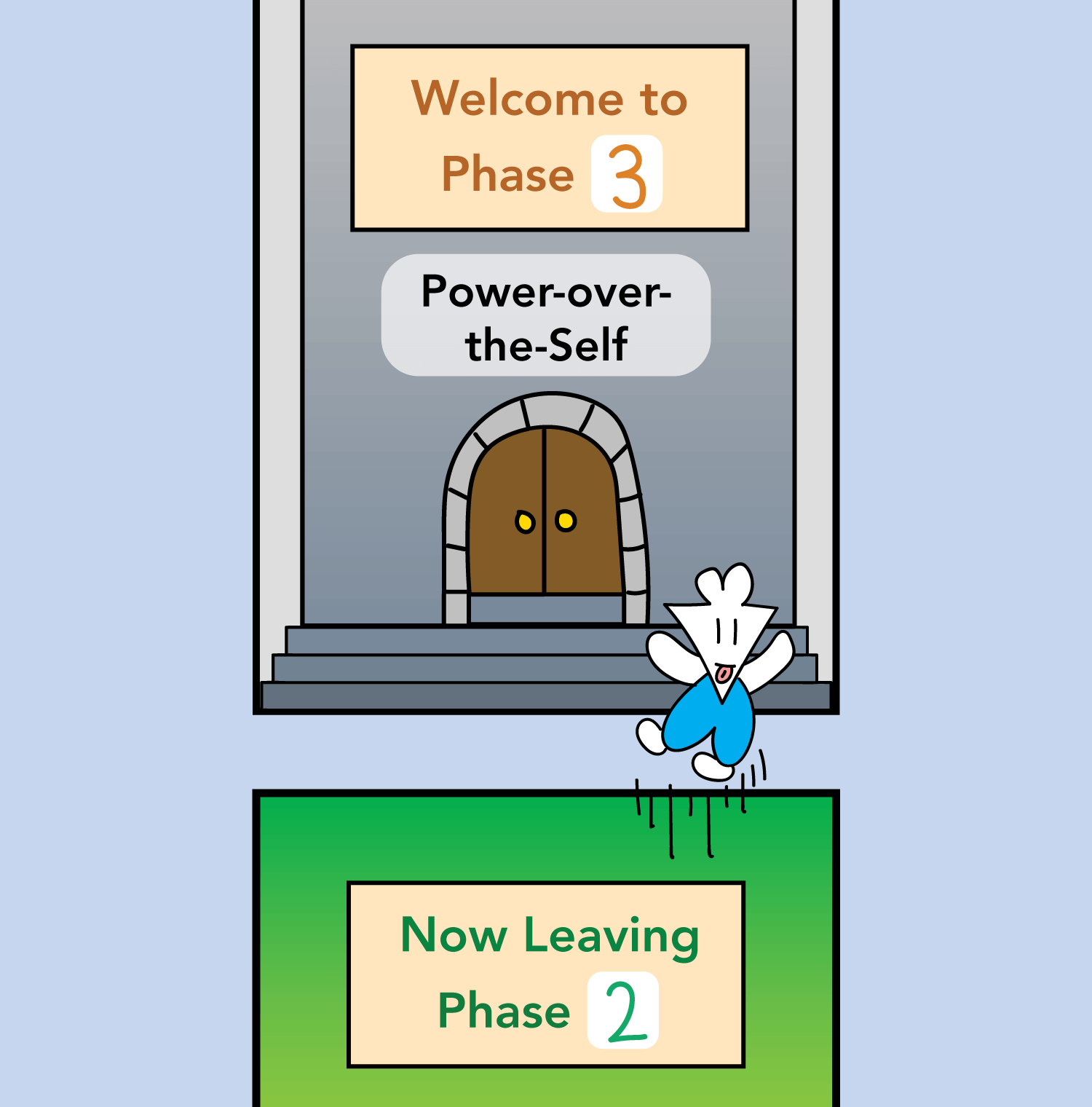

When you first cross the border between Freedom and Power on the Money Spectrum, you are making a seamless transition into Definition #1. With an abundant Fulfillment Surplus on hand, you are pursuing the things you want to pursue, while limiting the attention you give to the continuous demands of money.

I call this initial territory power-over-the-self.

We’re not going to linger here too long because it’s similar to the upper end of the Freedom phase, but there’s one important statement I want to go over before we proceed:

The way you exercise power over yourself will set the conditions for how you exercise power over others.

In other words, the way you express your autonomy will construct the views you have of others. And nowhere is this more apparent than the way we use our money.

If you want to express your individual power by buying yachts, wearing gold chains, and balling out at night clubs, then that does two things. First, it signals to others that these are the things that matter to you, and they will tie your human worth to your material worth. Second, you will view others through this same lens, and you will see materiality as the answer to solving their problems in turn.

This leads to a vicious cycle where money is how you’re viewed, and money is how you view the world. Emotions like love and sympathy are incredibly nuanced, and believing that you can express them with a crude tool like cash will put a nasty taste in the mouths of the people that matter most (more on this soon).

Understanding how you want to exercise your individual power is the key to navigating the next – and final – area of the spectrum: power-over-others.

“Power-over-others” sounds menacing, but remember, it simply refers to one’s ability to influence the behavior of others. The key question in this area is: how are you using money to direct the course of people’s lives?

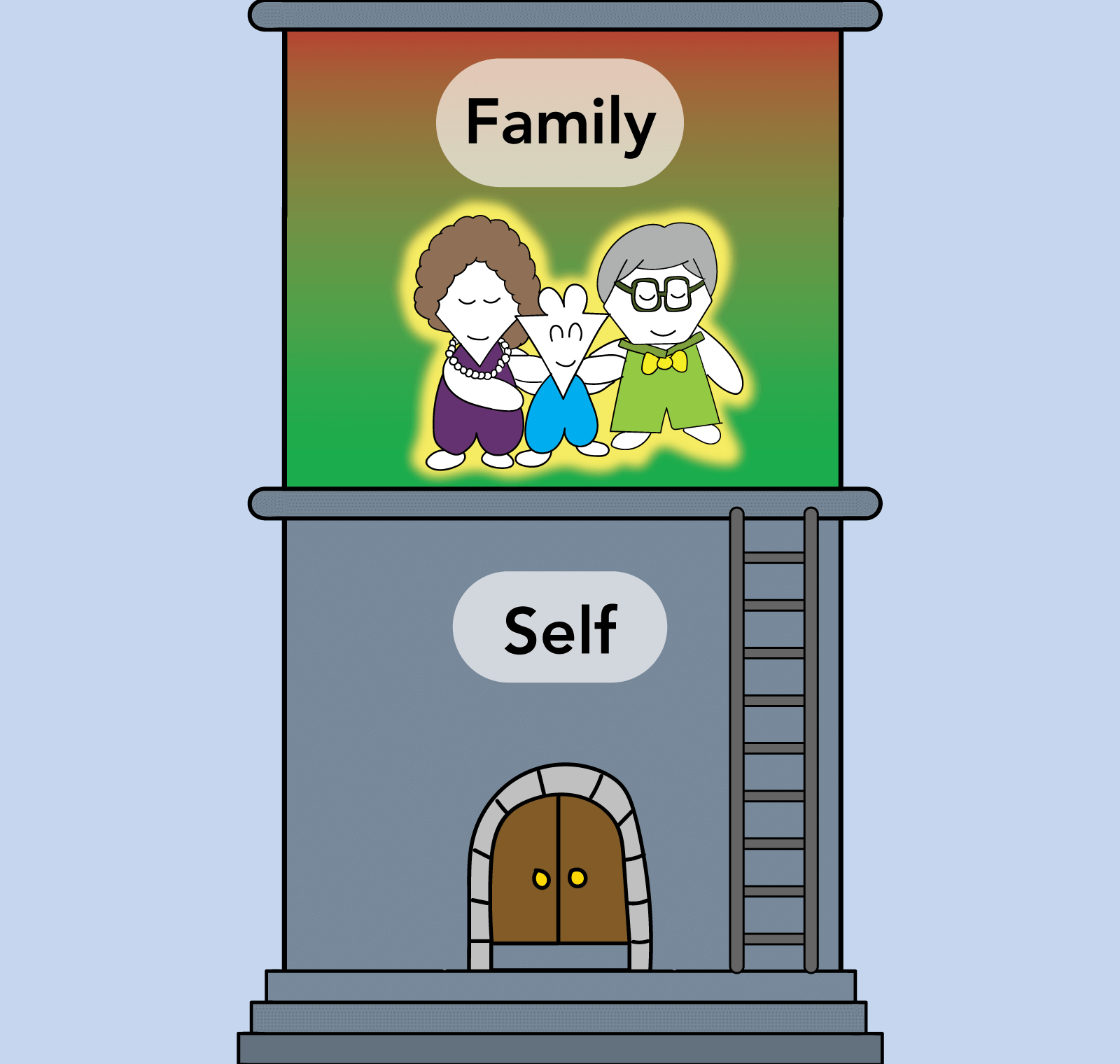

For most of us, the power of money resides in its ability to provide a better life for our families. With this precious resource, we are able to provide a better education for our children, larger homes for our partners, and grander vacations for our parents. These things provide a solid foundation for our family’s futures, and will direct the course that these lives will ultimately take.

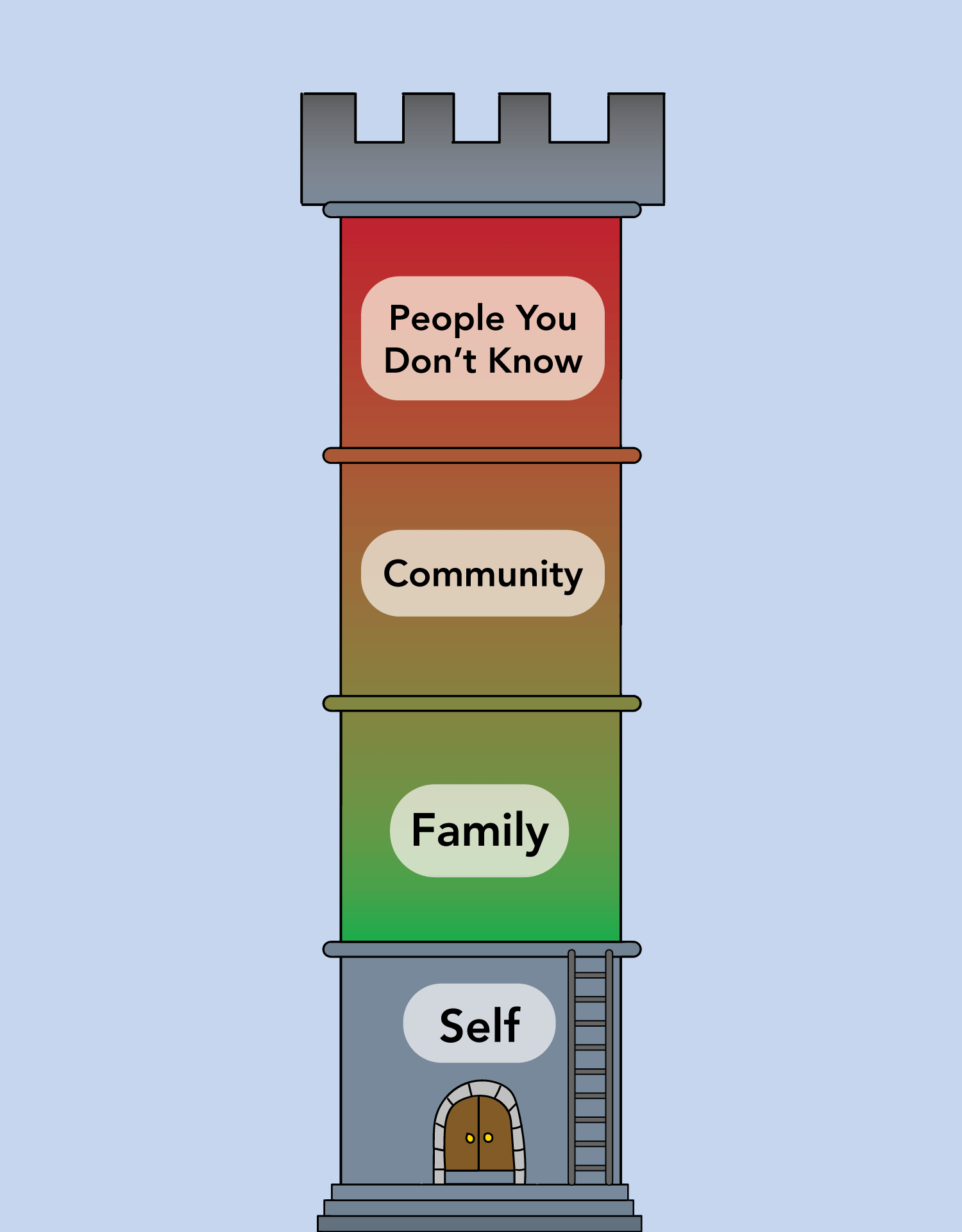

If influence were a tower, the immediate level up from the self would be the domain of family. The power of money in this realm is immediate, as your loved ones will see evidence of it in the form of higher-quality life experiences.

However, that doesn’t mean that the power of money will always yield a better family life. In fact, the reverse can be true: the more you elevate the importance of money, the more you may be (unintentionally) isolating yourself from them.

This is where the greatest distinction between Power and Freedom resides. The upside of power is generally capped, whereas the upside of freedom is not. With power, there is usually a point where more of it starts having an adverse effect. If the influence over others becomes too great (even if it’s in the name of well-being), it can breed distrust, envy, and resentment.

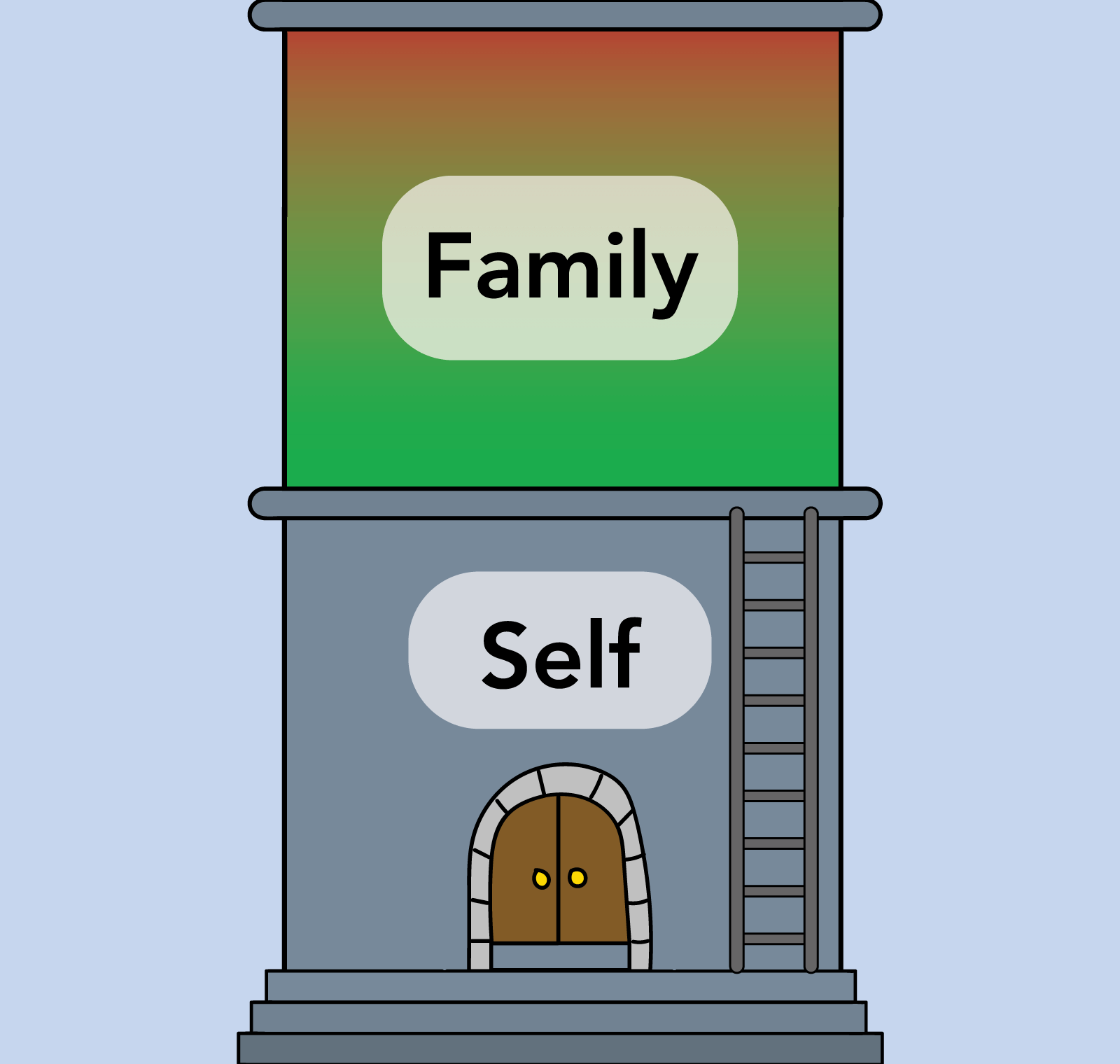

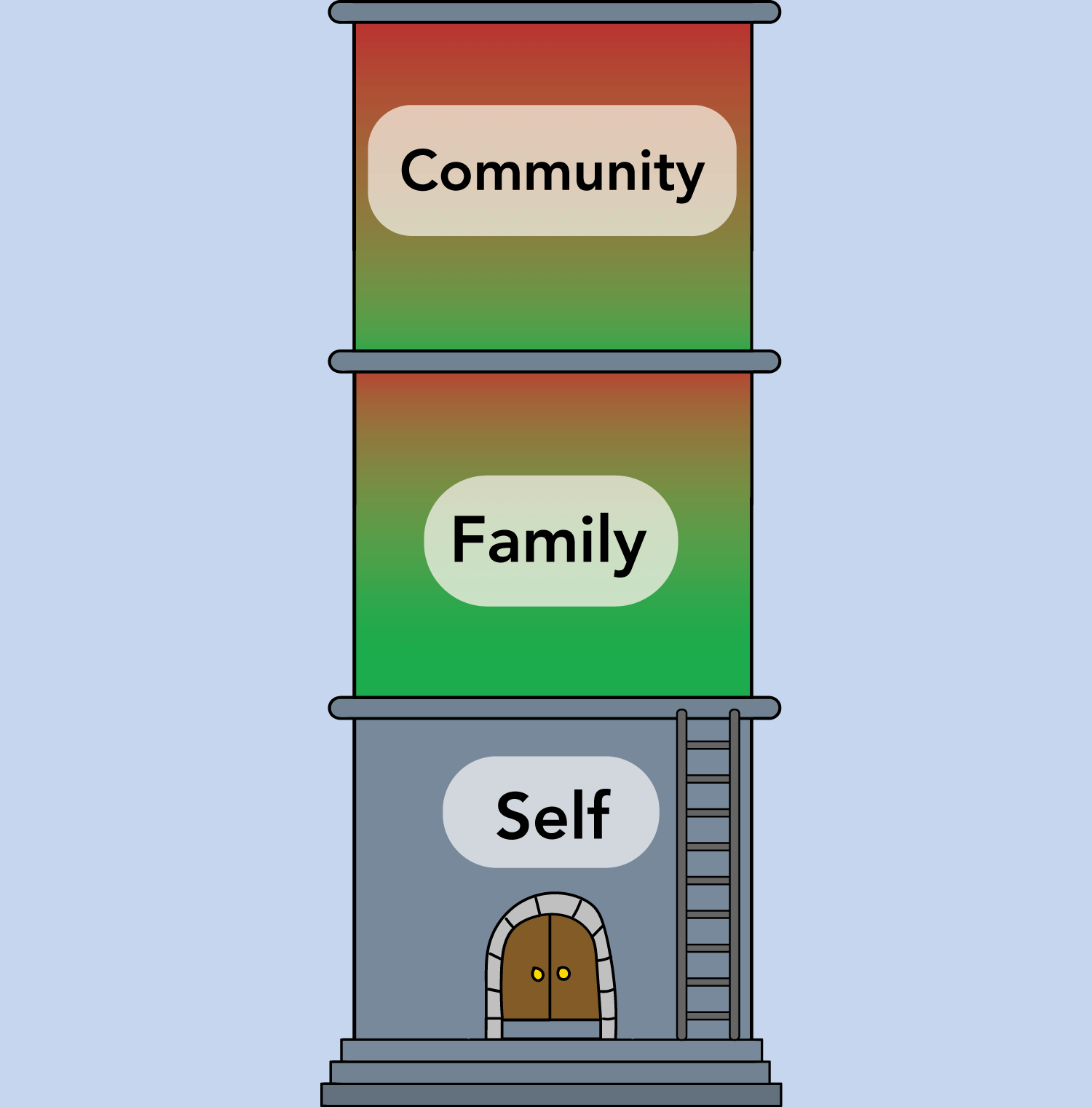

Baked into each layer of influence is the Power Tradeoff, where the green area represents the benefits of having the power of money, and the red signifies its more detrimental aspects.

The above image shows the family layer’s Power Tradeoff, where both green and red areas exist. The green part should come as no surprise – the main reason why people work so much is so they could provide for their families. The more money they make, the more power they have to elevate the well-being of their loved ones.

The red part represents the other side of the story. There are many children who never get to see their parents because they’re out working 90-100 hours a week. They might live in a huge house with all the things they want, but the sense of abandonment can morph into resentment.

This red section is what happens when you forget that pursuing your idea of power has a deep effect on others. Many parents believe that working hard and making money is how they express their love for their children, but miss the fact that their children may not see it the same way. This leads to situations where these parents work tirelessly to become millionaires, only to see that their relationships with their kids have been defined by lost opportunities.

However, in this Power Tradeoff, the green still outweighs the red because we are eventually able to understand the nature of sacrifice. As long as we know that our parents love us, we are able to empathize with their plight, and understand the hustle they put in to provide better lives for everyone. This may take time, but if rationality prevails, these types of family difficulties can be healed in the long run.

Many people will stop here in the tower of influence. They might be content in providing for themselves and their family, and won’t progress through additional power structures. But more likely, if those two layers are fulfilled, they will look to help or influence the health of the close-knit groups they’re a part of.

Next up is the domain of community.

So what does the Power Tradeoff look like here?

People in your close communities know you quite well, and you are generally together for some shared purpose. That glue might be religion, it may be service, or it could be something more value-free like entertainment. Regardless of what it is, this purpose is distributed across each of its members, and equalizes everyone’s role in this communal playing field.

Influencing the community through money, however, can complicate the situation.

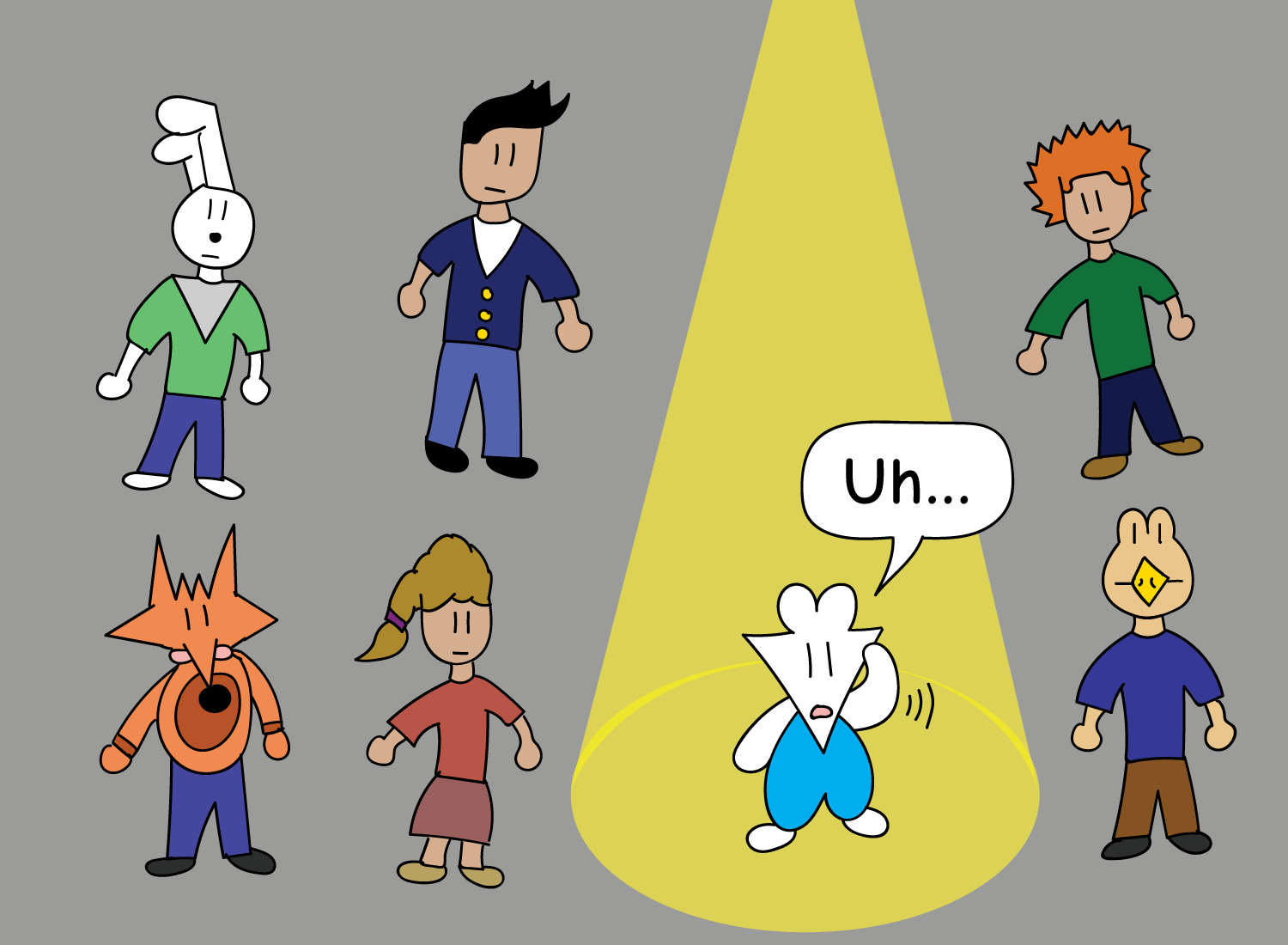

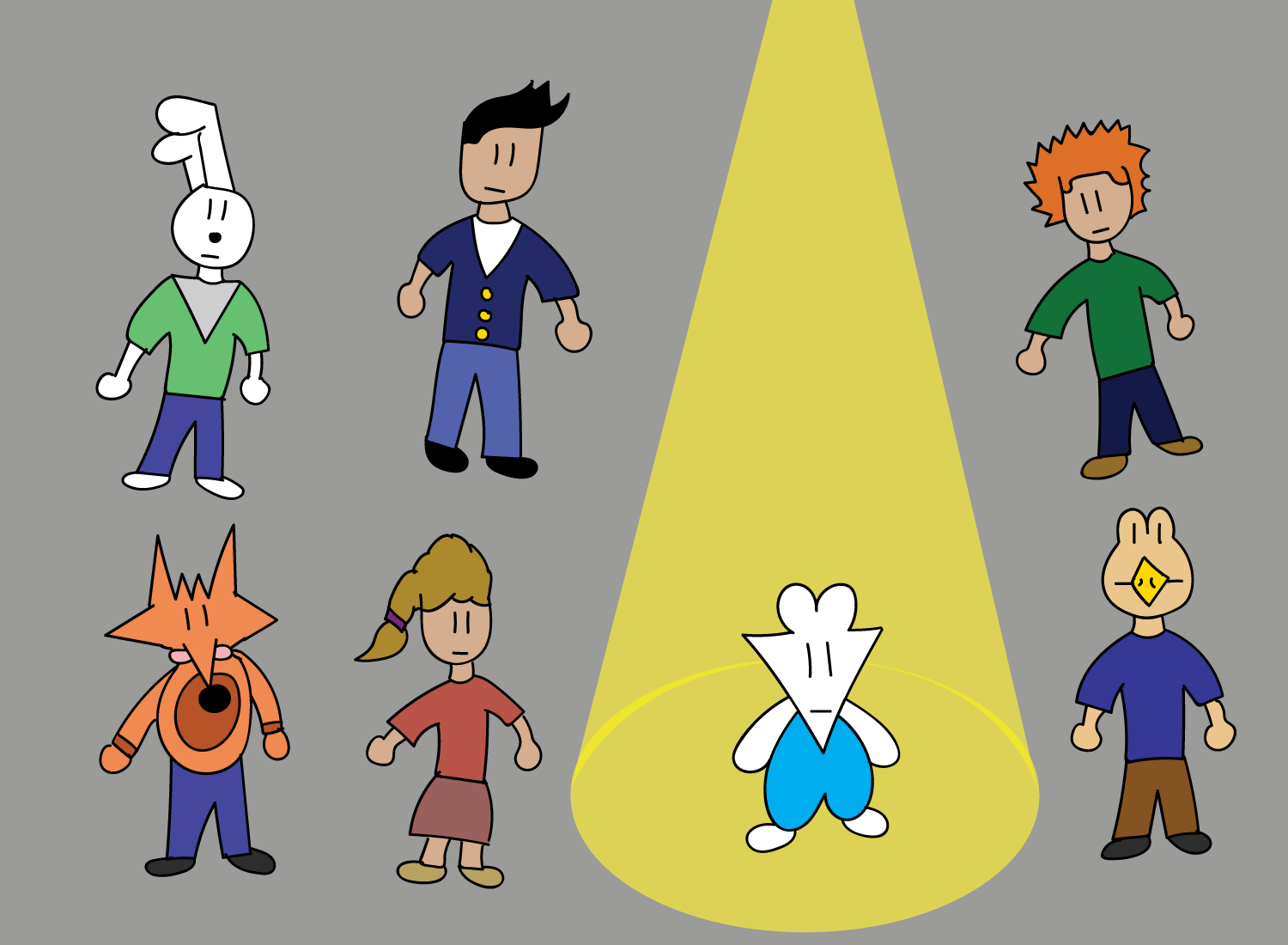

If you decide to make an outsized donation and everyone hears about it, this is likely to happen:

The tricky thing with money is that it’s often used as a measuring stick of one’s value to their community. If you give a lot of money to a cause you care about, that might be the way people gauge how much that cause means to you, as nuance tends to be removed the larger the group is.

I mentioned earlier that financial freedom is obtained by the elimination of attention, but the reverse is also true. Financial freedom is diminished by the constant receipt of attention as well.

The more you are viewed through the lens of money, the less you are able to break free from the identity of money. For some, that may not necessarily be a bad thing. Perhaps you’re a financial advisor, and your personal wealth has to be a reliable signal to others that you know what you’re doing.

But if you just want to elevate the financial health of your local church, being “that person that gives a shitload of money” can be a cumbersome role to play. Money is a low-resolution surrogate for your value judgments, and sadly, many people have a hard time making this distinction.4

The closest members of your communities, however, may be more nuanced in their perceptions. They may not be as close to you as your immediate family, but they can understand your principles, your values, and the things that make you who you are, independent of wealth.

In the community layer, the Power Tradeoff is still more positive than negative, but not as much as the family layer below. The impact of money can go far, but since there are more people involved (some of whom you may not even know), the many shades of your identity can start congealing into the singular dimension of wealth.

The balance is finer here. Use your money mindfully, and the community will thrive with you. Use it recklessly, and you will be vilified by the very community you were trying to help. Money can breed all kinds of weird group behaviors, so your judgment must be sharp when navigating this domain.

For the vast majority of us, this is where our desire for influence (as it relates to money) will stop. Having the power to help people we know yields a sense of fulfillment, and that is enough to keep us contented for the rest of our lives.

However, there are some people that want to go beyond their immediate circles, and use their money to direct the behaviors of people they don’t know at all. They want their wealth to go far, and act as the tool to spread influence over the lives of many. This type of power can range from the smaller scale of things (local non-profit groups, influencing district elections, angel investing, etc.) all the way to the largest scale we could think of (global philanthropy, influencing presidential elections, big venture capital firms, etc.).

To simplify this massive range of possibilities, let’s all throw them into one final layer titled “People You Don’t Know.”

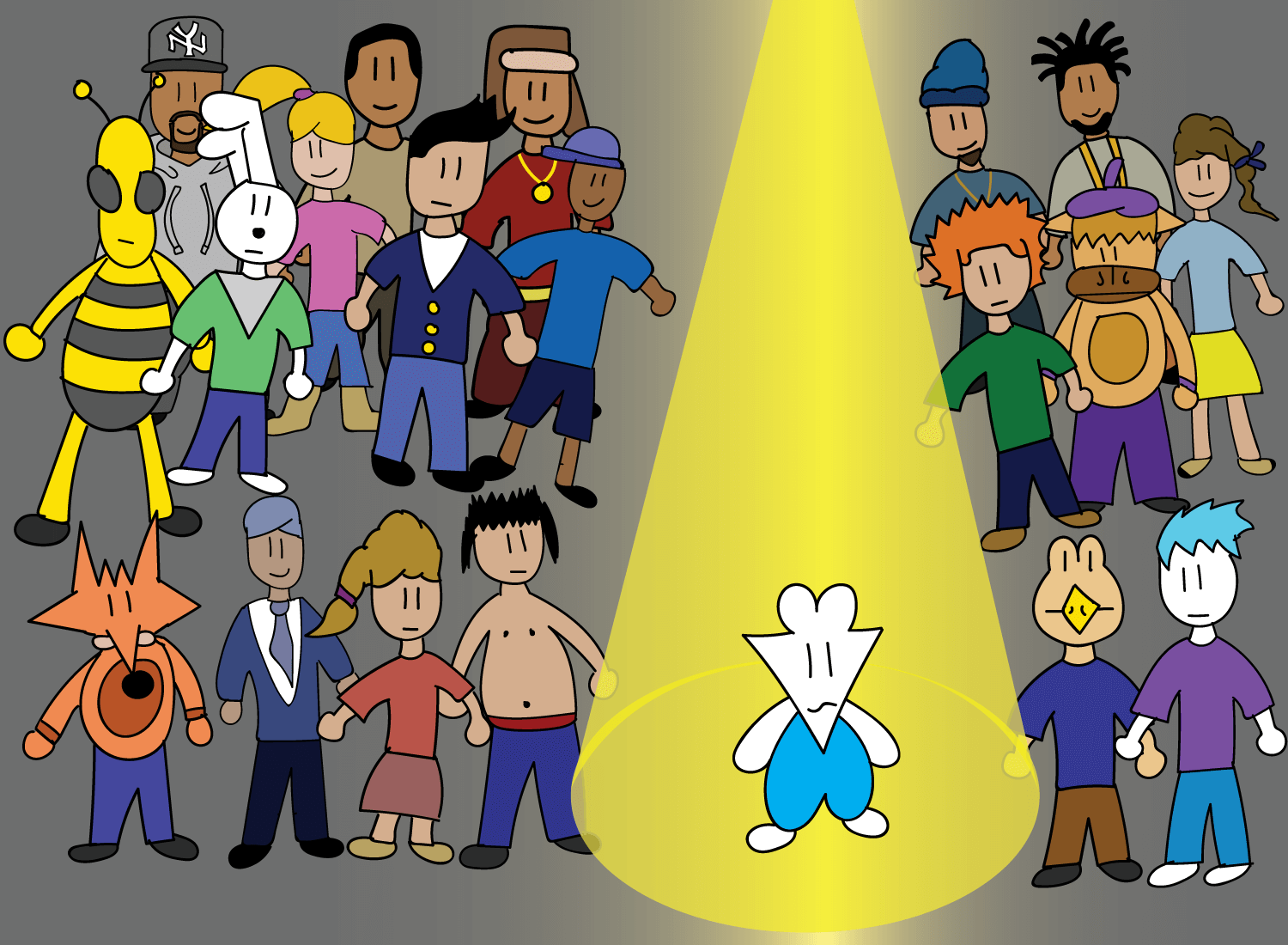

Of all the layers in the tower of influence, this one is by far the riskiest. This is where “power + money” gets its shitty reputation, and people tend to be skeptical of the folks that operate here.

To illustrate why, recall this scenario from the community level:

And realize that when you’re operating at the “People You Don’t Know” level, you get this daunting situation:

With that much attention to your financial decisions, it’s easy to be perceived as a caricature of your money. People that don’t know you are indifferent to the relationships you have with your neighbors, the fact that your sister may be ill, or the details of your daily meditation practice. You are defined primarily by your wealth, and what you do with your wealth shapes the perceptions of your character.

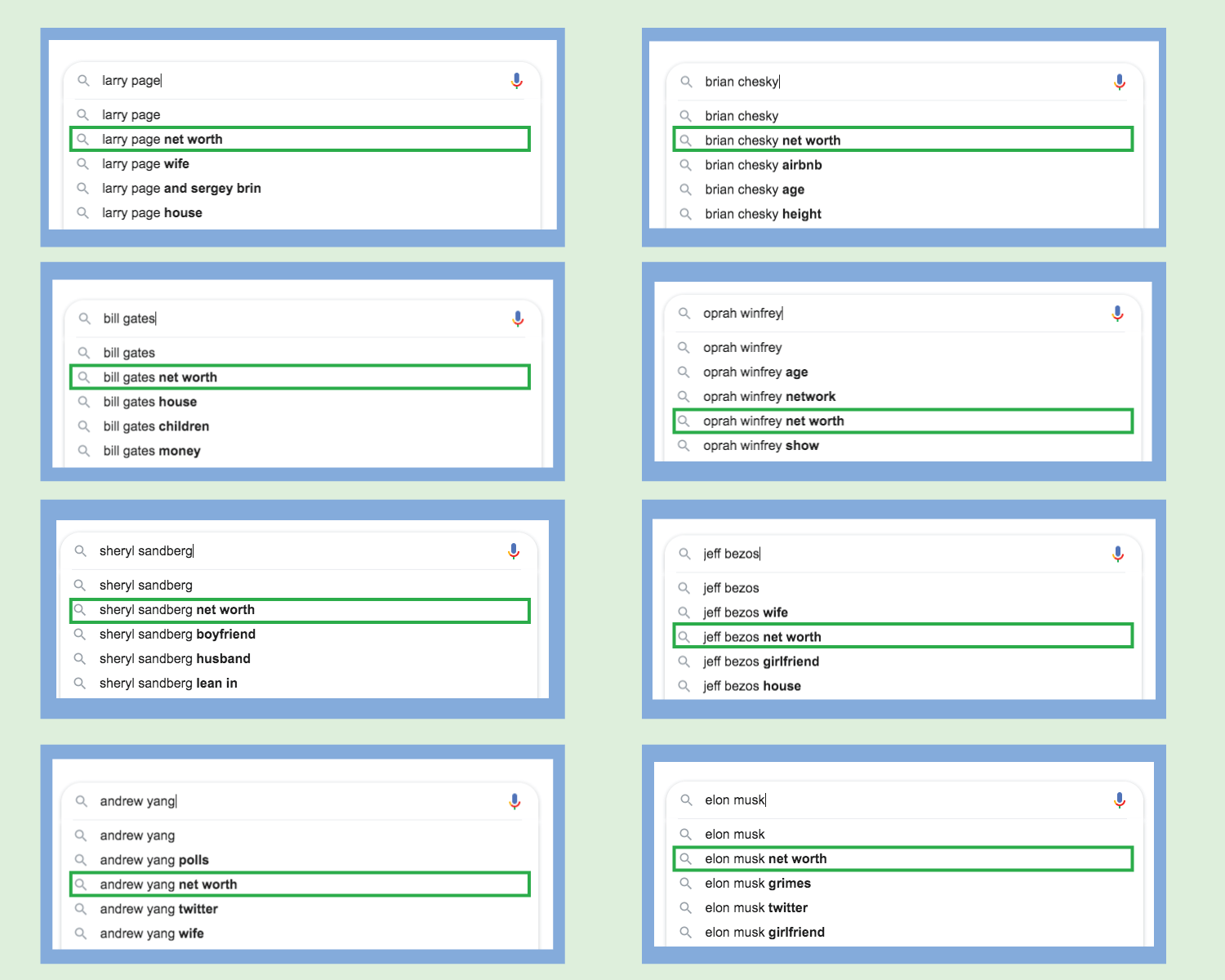

You may think I’m overgeneralizing here, but when you mix wealth into someone’s list of attributes, everything else seems to go out the window. Want to see evidence of this? Put the name of any prominent businessperson or entrepreneur in Google, and guess what will always pop up as a top search suggestion:

This singular view of identity is the source of most problems on the “People You Don’t Know” layer. If everyone knew you as an artist, you couldn’t help but to see the world through the lens of creation. Similarly, if everyone used wealth to define you, then you will likely solve problems through the lens of money.

Sometimes this works out well for humanity. For example, Bill Gates is using his power to help solve some of the world’s greatest problems. But for every Bill Gates, there may be thousands of people that want their money to influence others in less fruitful ways. Political corruption and racketeering are just a few examples here. When money is used to solve big problems in zero-sum games, it usually comes at the expense of the powerless.

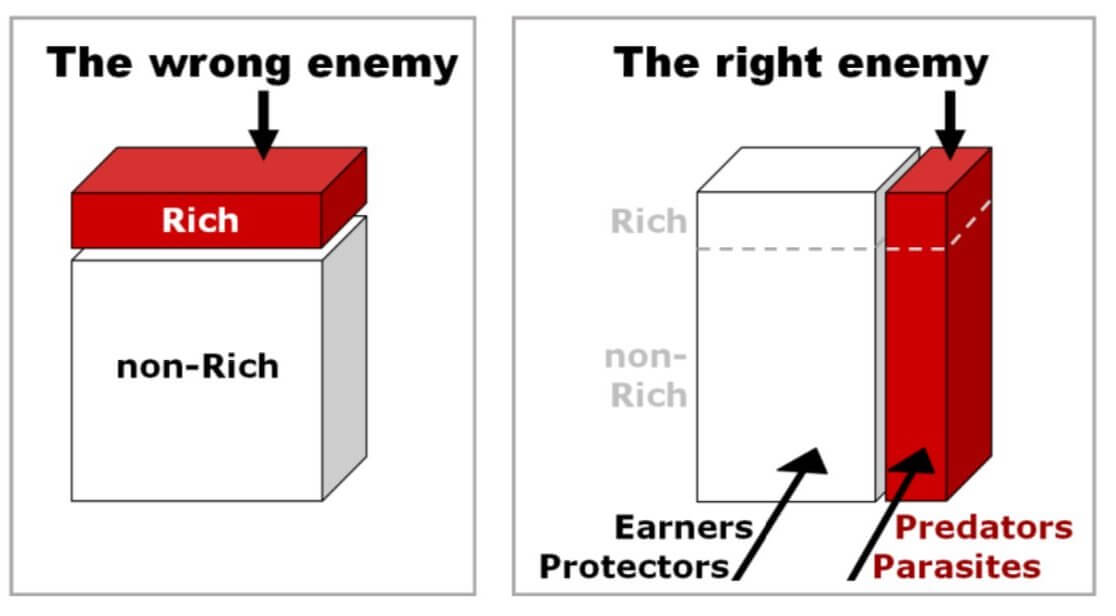

But of course, being rich and powerful doesn’t imply that you’re evil. The truth is far from that. I’m reminded of this great illustration, which depicts the reality of the situation:

This image is from Steve Conover’s book, Neutering the National Debt.

There are plenty of wealthy, influential people that have the best intentions in mind. The point I’m making, however, is that operating in the “People You Don’t Know” layer of influence is a tricky place, primarily because it tends to cultivate the feeling of attachment.

I don’t have the personal wealth to operate in this final layer, but I imagine that much of the struggle here comes from the inability to detach one’s wealth from the rest of their persona. I’ve read cases about executives (and even a billionaire) committing suicide because they lost money in the 2008 recession. That might sound crazy to someone like me, but then again, I don’t know what it feels like to have my personal wealth define my entire existence.

Money is a tool, but if that tool defines how you impact the lives of thousands of people, it will be of utmost importance for you to continue having it.

And when it comes to attachment, these three words sum it up well:

Ironically, the end of the Money Spectrum can breed just as much fear as the Survival entrance into it. Having immense power can make someone just as fearful of losing their money as a person who needs it to survive another day.

This tendency toward attachment is what makes the Power Tradeoff in this final level an unfavorable bet:

Now that we’ve colored in each layer, let’s take a step back and look at the tower of influence in its entirety.

At the moment, it looks like a collage of individual red-and-green spectrums, but if we blend them all together to create an average Power Tradeoff for the whole thing, it’ll look something like this:

This is a good summarization of what the Power phase looks like on the Money Spectrum. Money can work well for you in the domain of the self and the family, but it can create attachment when it gives you power over many people. When your identity becomes defined by the influence of money, you are wading into dangerous waters, and you will have to exercise brilliant judgment to navigate through it properly.

At the same time, if your judgments are right, you will be able to do immense good. Just consider all the tradeoffs that exist toward the end of the Money Spectrum, and understand how your decisions ripple through each subsequent layer below it.

Where Are You On The Money Spectrum?

We’ve conducted a comprehensive review of all three phases, so now it’s time to zoom out and see the Money Spectrum as a whole.

The first question I ask myself when I see this is, “What determines someone’s place on this spectrum?”

The initial assumption here might be the amount of money you have. After all, if you have no money, you’re probably scraping for survival, but if you have a lot, you can exercise great freedom and power with it.

But this is simply not true.

You can have a modest sum of money, but live high up on the Freedom phase. A good example would be someone that makes $30K a year, but earns it doing work she loves. On top of that, she lives a lifestyle where she reliably spends just $20K a year. She has freedom-in-work, and power-over-the-self. She is a rich person.

Conversely, you can have a large sum of money, but be low on the Survival phase. This would be someone that makes $300K a year, but earns it doing work he hates. On top of that, he lives a lifestyle where he is racked up in credit card debt, with a mortgage on a house he can’t even afford. He has limited freedom, and is barely scraping by. He is a poor person.

There are many variations of this that highlight the inadequacy of the “money-in-the-bank” metric. There are many millionaires that have no desire to influence or help their families and close communities. On the other hand, there are people earning a minimum wage that send what little they have back home to assist their parents and friends.

The amount of money you have is not the proper lens to view your place on the Money Spectrum.

So if money itself doesn’t determine your place on the Money Spectrum, then what the hell does?

Well, the answer may sound trite, but it’s the truth.

You choose your position yourself.

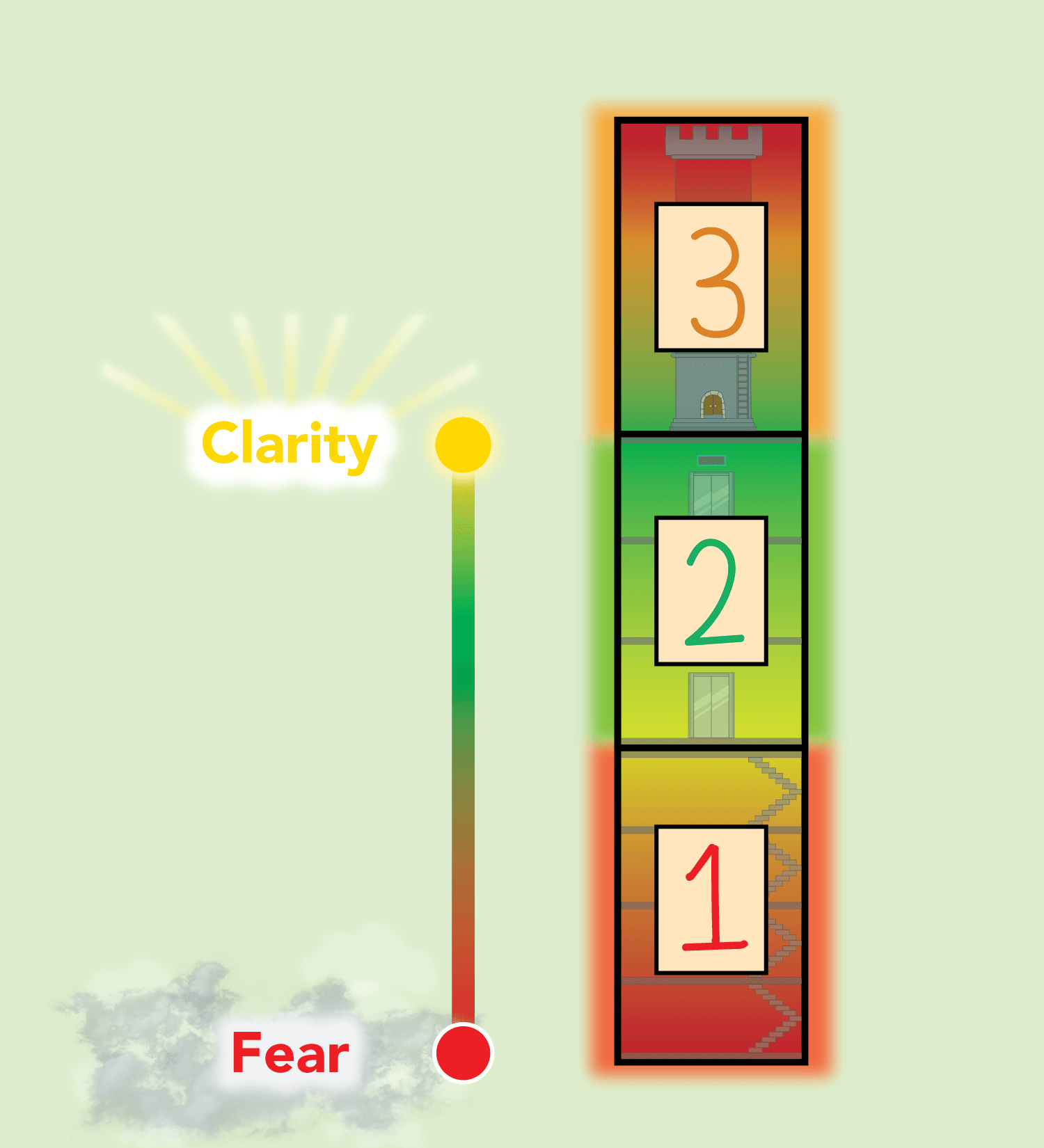

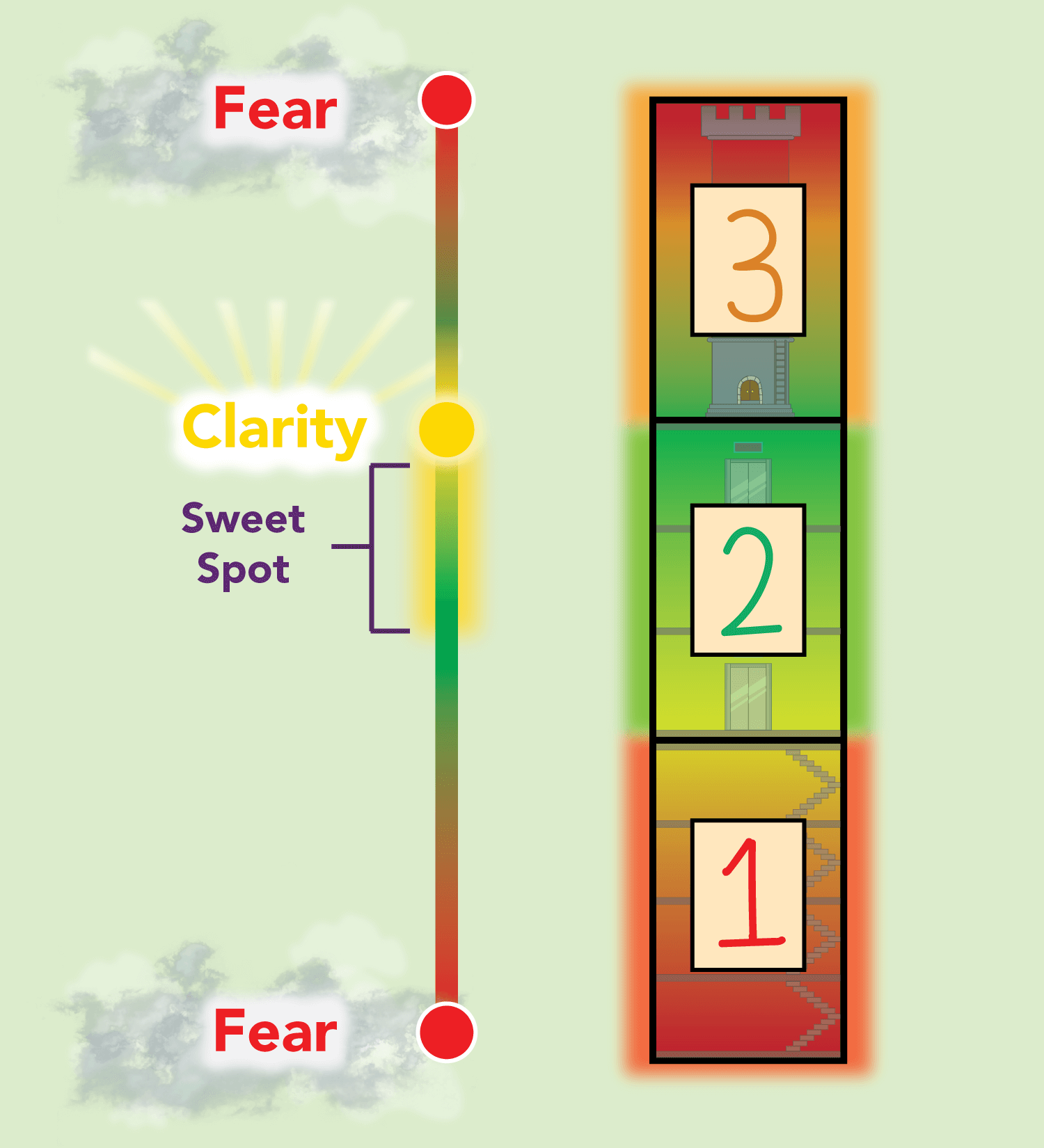

To understand what I mean, we need to first view things through the right frame. Instead of viewing the spectrum through the lens of how much money you have, you must view it through the emotional ranges of two things: clarity and fear.

The lower you are in Survival mode, the more fearful you are of money and its impact on your life. However, as you move up the Survival phase and get closer to Freedom, the fear surrounding money gradually fades and things enter the domain of clarity.

When you’re in the Freedom phase, things are more clear, but freedom-in-leisure is still a somewhat hazy place. You start having more control over your life the higher you go, and the greatest benefits come when you’re in the freedom-in-work and the freedom-in-attention areas of this phase.

This is what I call the sweet spot, and it is where your wealth goes the longest way, regardless of how much you have.

If you make the decision to proceed further into the Power phase, then you must enter the tower of influence, where Power Tradeoffs become increasingly tenuous the higher you go. Exercising your influence through money may be more manageable with your family, but once it goes into the layers of communities and people you don’t know, there’s more at stake. Attachment can become fervent, and fear can dominate the spectrum once again.

The Money Spectrum makes the most sense when you view it alongside this gradation of emotions. It helps you understand that money is not something you own, it’s something you have a relationship with. And just like the people you choose to have around you, it’s a bond that is shaped with intention and care.

Of all the things that define your place on this spectrum, the most important one is your identity. Which phase do you see yourself in the most?

If you view the world through the lens of scarcity and survival, money will only amplify that feeling of inadequacy. But if freedom is what defines you, then money will feel abundant, no matter how much you have. If power and influence is what you want, then money will drive the nature of your relationships in that direction.

Where on this spectrum do you think you are now? And where do you want to be? What’s holding you back? Is it money, or is it your mentality?

Be honest with yourself when asking these questions. Your identity will inevitably answer them for you, but you don’t want any surprises when it does.

After all, if you don’t give money its purpose, it will end up defining yours.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

How did money take over humanity? The full story is here:

Money can take you all over the world, but travel won’t bring you happiness:

Travel Is No Cure for the Mind

A reminder that money (or any other thing) won’t give you meaning either:

But here’s a reflection that will help put everything back into perspective: