The Levers That Money Can’t Pull

When I was in high school, my mom told me a story that had me in tears.

One weekday afternoon, she was coming back home from work when she got a knock on the door. The rhythm of the knock sounded frantic, and sure enough, when she opened up, our neighbor was on the other side, sobbing while holding a crumpled piece of paper.

If there’s one word to describe the community I grew up in, it would be tight-knit. Most of my neighbors were also my mom’s co-workers at a local Korean food catering business, earning a minimum wage preparing meals for nearby office workers. We saw each other almost everyday, joking around and pretending to be Kobe while shooting around on a makeshift hoop.

From a fiscal standpoint, we were poor. But from a communal standpoint, we had everything we ever needed.

The neighbor at the door was the youngest of my mom’s co-workers, but had the biggest heart. She was the mother of two sons, both of whom I consider friends to this very day.

To make ends meet, she worked two jobs: one preparing food with my mom at the catering business, and the other at a market packaging Korean side dishes. It was a difficult way to earn a living, but it was enough to pay the rent and provide her children with what they needed.

And with what little she had left over, she gave some of it to me to tutor her eldest son, John (not his real name).

John was an incredibly disciplined guy, waking up at 5 AM each morning to go for a 3-mile run before school started.1 Given his aptitude for regimen, she knew that he had the potential to get a great education and earn a good living as a result.

John, however, didn’t think that college was the right move for him. He found much of academia to be tedious, and he struggled his way through school and the exams that accompanied it. His GPA didn’t reflect the depth of his intellect, and he interpreted that as a signal to look for an alternate path.

After a brief search, the path he landed on was with the U.S. Army.

His plan was to serve in the Army for 4 years, then go to college afterward. This meant that his mom wouldn’t have to shoulder any of the financial burden associated with school, given that the Army would pay for the entire experience after he served his time with them.

While this sounded like a straight-forward plan, there was one fact that John’s mom couldn’t ignore:

The year was 2004, and the Iraq War was in full steam.

After John was sent to training camp, his mom was constantly worried about whether or not he would be deployed to Iraq. And sure enough, not too long afterward, she was notified that he was going to be sent there for active duty.

At the time, when someone was deployed to Iraq, the government sent a check to their family as a consolation of sorts. And on that afternoon where John’s mom knocked on our door, she received a check in the mail in the amount of $10,000 that resulted from John’s deployment.

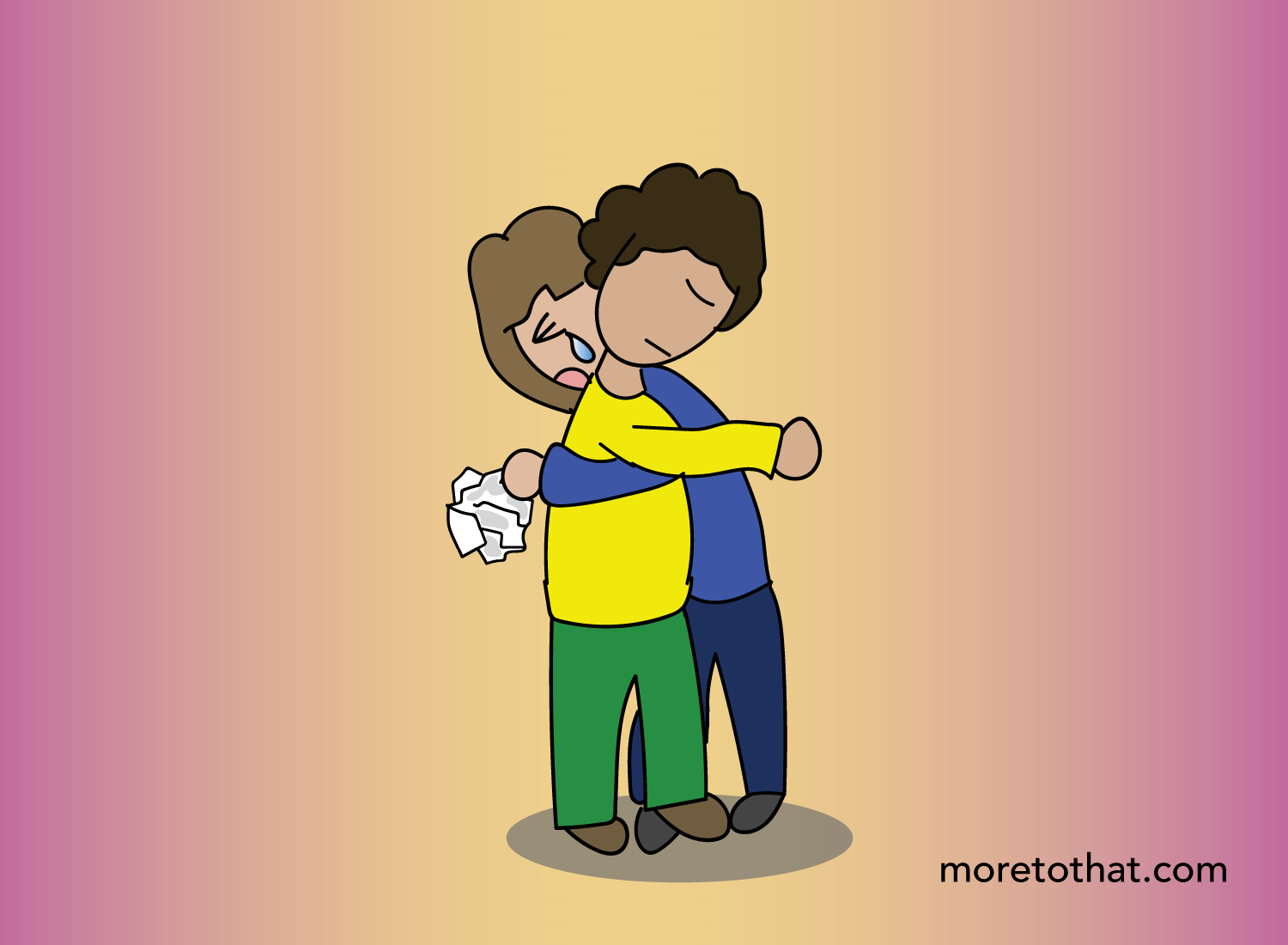

This was the paper that was crumpled in her hand as she sobbed in front of the doorway. And the first thing she said when she fell into my mom’s arms was:

“I feel like I sold my son.”

My mom consoled her, not just as a friend but as a fellow mother. She understood why John’s mom felt that way, even if that feeling was irrational. She knew that when your child is placed in a life-or-death situation, a parent would feel wholly responsible, even if they didn’t make any of the decisions that created the situation in the first place.

So while John was the sole agent that chose this path, his mom couldn’t help but to feel that if money were no issue, this path wouldn’t have been an option in the first place. That if money were abundant, John would’ve simply taken some time off or have explored the world in peace. And what made this feeling stronger was the check that put a price on John’s deployment, which made her feel that she facilitated a sale which implied the trade-in of John’s life.

Well, fortunately, that nightmare didn’t come to fruition. John ended up surviving his time in Iraq, and it was only after his return where my mom told me this story. I’m not sure if she simply forgot to tell me the day it happened, or if she thought it was better to store it away in her heart and let her voice recall it when a brighter day arrived. If I had to guess, it was probably the latter.

So when my mom finally told me this story, I had the privilege of knowing that John was all right, but I still couldn’t help but to cry. Not only because I loved John’s family, but because I realized that John’s mom felt an emotion that I wish didn’t exist. An emotion that’s also felt by millions of other people, many of whom we have no window into, but nonetheless are feeling it each day.

And the feeling is this:

A terrible shame accompanying the lack of money, which makes you believe that you’re less of a person as a result. That by not being wealthy, you’re less of a parent. That by making a low income, you’re a lowly son, daughter, or friend. That if only you weren’t so poor, you’d be the ideal person or caregiver you envision yourself to be.

John’s mom felt an emotion that no parent should ever have to feel. But she felt it because she was viscerally aware of her financial limitations. If $10,000 was a mere rounding error, then that check wouldn’t have evoked the feeling that she sold her child. But since $10,000 was a consequential figure that would have an immediate impact on her financial situation, she felt terrible that this benefit accrued at the expense of her son.

What saddens me most is that John’s mom is one of the kindest people on the planet, yet the question of money made her feel like an immoral monster. Anyone who knows her would extol her virtues to no end, yet within the boundaries of her mind, her thoughts were convincing her that she was a terrible person. This is what people could experience when money is believed to be the reason why they’re not the best version of themselves.

The difficult thing about this sentiment is that there is some truth to it. If you live in poverty, then the path to self-actualization is at a steep incline if you’re fortunate, and completely barricaded if not. Without money, your time will be bound by the sole pursuit of it, and you will never feel like you have the headspace required to fulfill your potential.

With that said, this line of reasoning only highlights a part of the picture, and we need to zoom out to get the full image.

When we think of a capable human being, there are certain characteristics that come to mind. Someone that’s smart. Someone that’s wealthy. Someone that spends their time the way they want to. In other words, we think of someone that embodies freedom, and directs that freedom toward creating and harnessing opportunity.

Freedom is one of those virtues that money actually can buy. In fact, it’s the greatest thing that money can purchase, as the ability to choose what problems to solve (and the manner in which you’ll solve them) is enabled by having control over your attention. Ultimately, money affords you with the ability to close the doors you don’t want opened, and to open the doors that were once closed.

While all this is true, we need to remember something important:

The attainment of freedom may signify a capable human being, but is far from signifying a compassionate one. And while you may be eager to learn from competent individuals, the people that you will appreciate most are the ones that have the greatest capacity for love.

So instead of valuing yourself solely based on the freedom you embody:

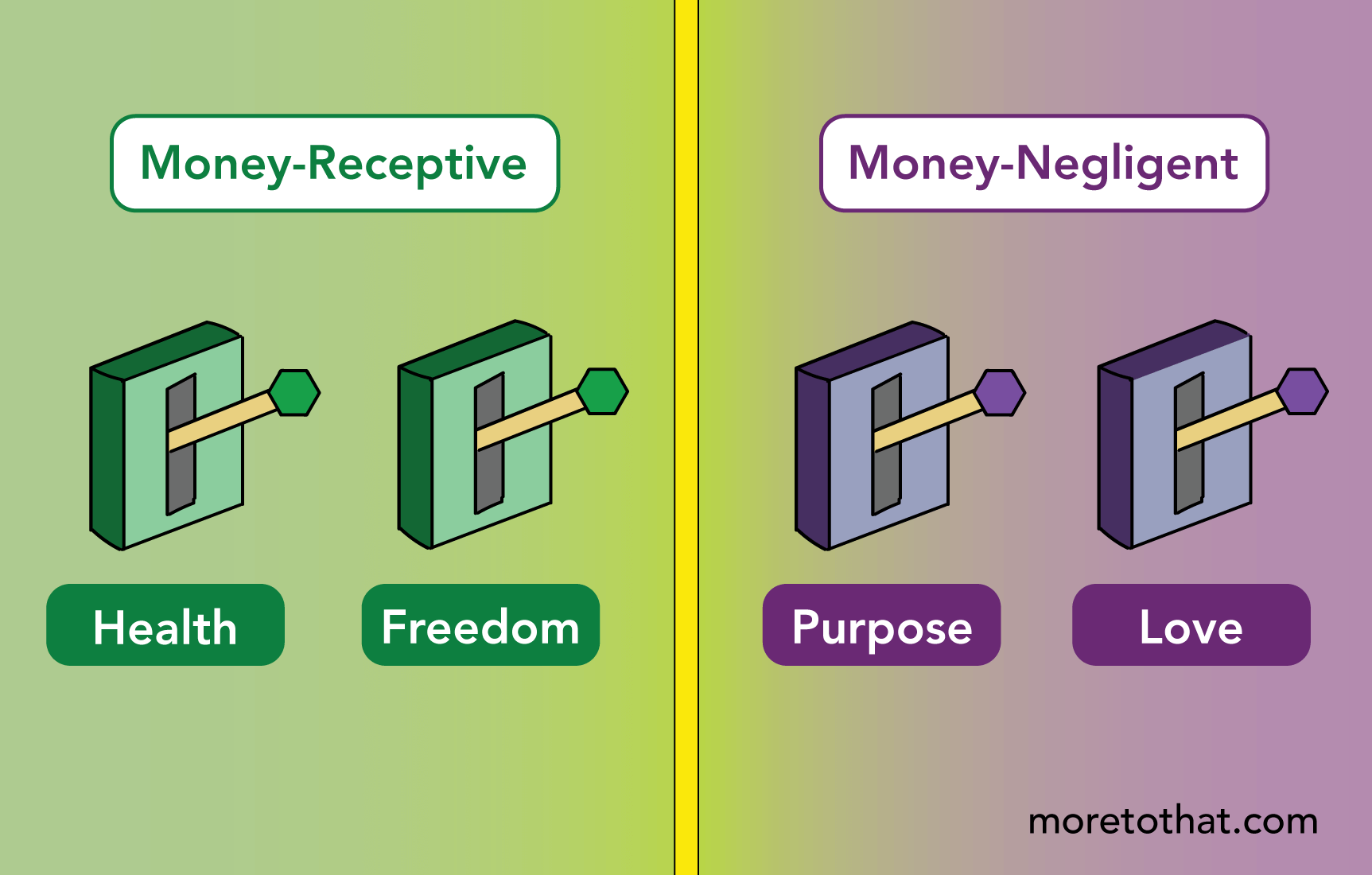

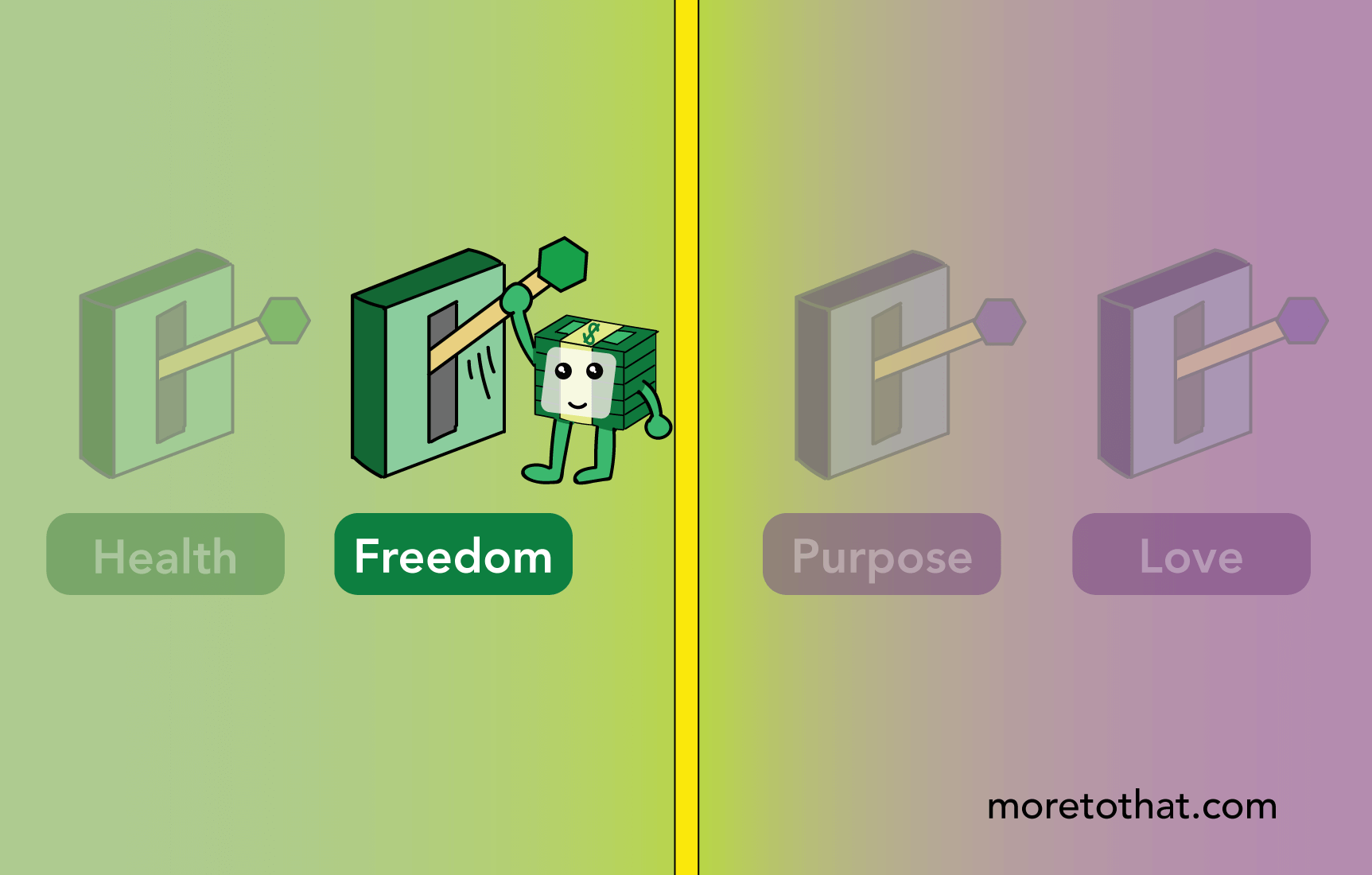

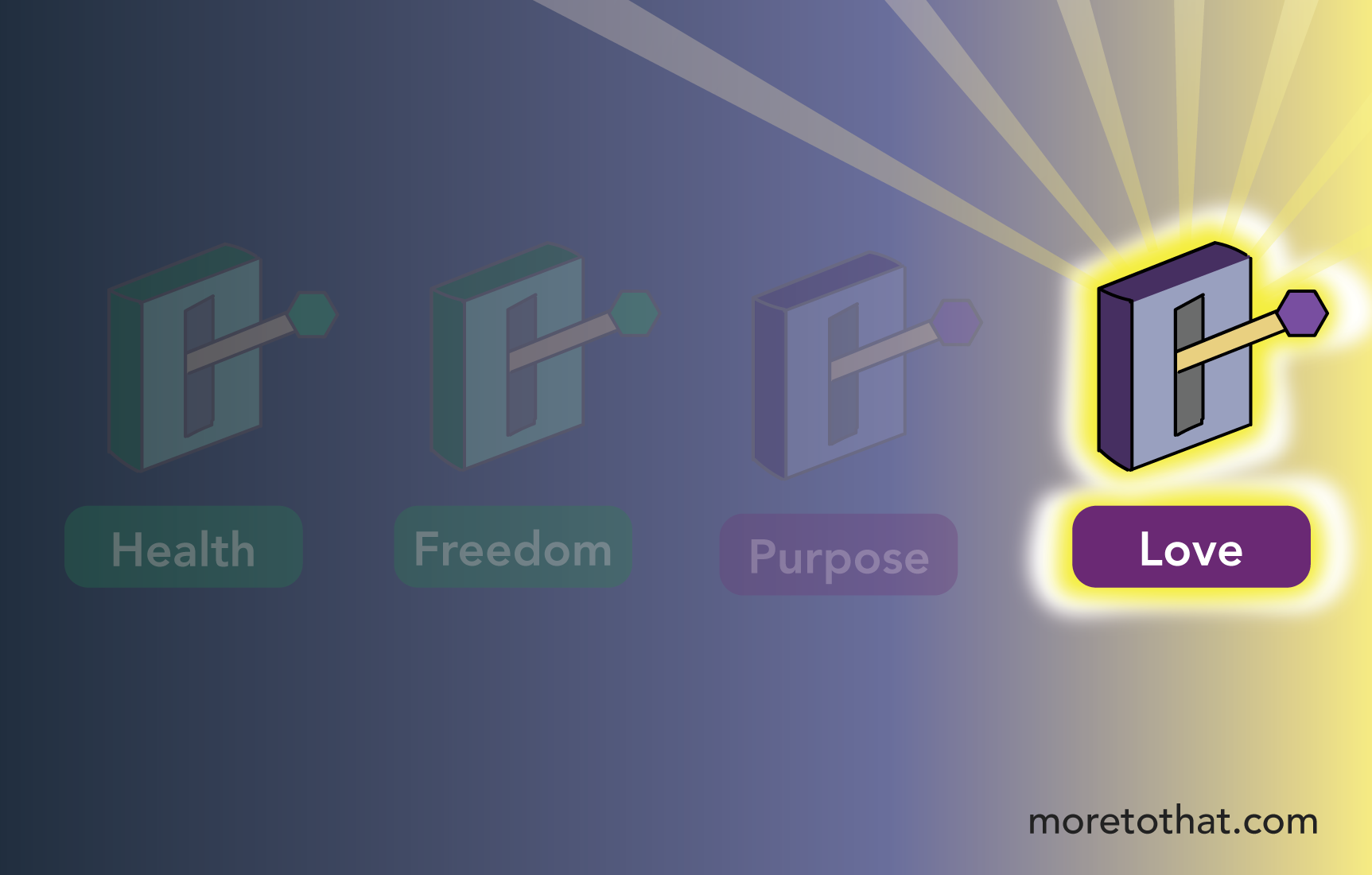

It’s important to take a holistic view of what it means to live a life well-lived, which comes down to the fulfillment of four things:

These four parameters are the forces that guide every person’s life, regardless of culture or creed. Everyone wants to be healthy, to be free (through wealth or ideology), to have a sense of purpose, and to be loved. No human being is exempt from this.

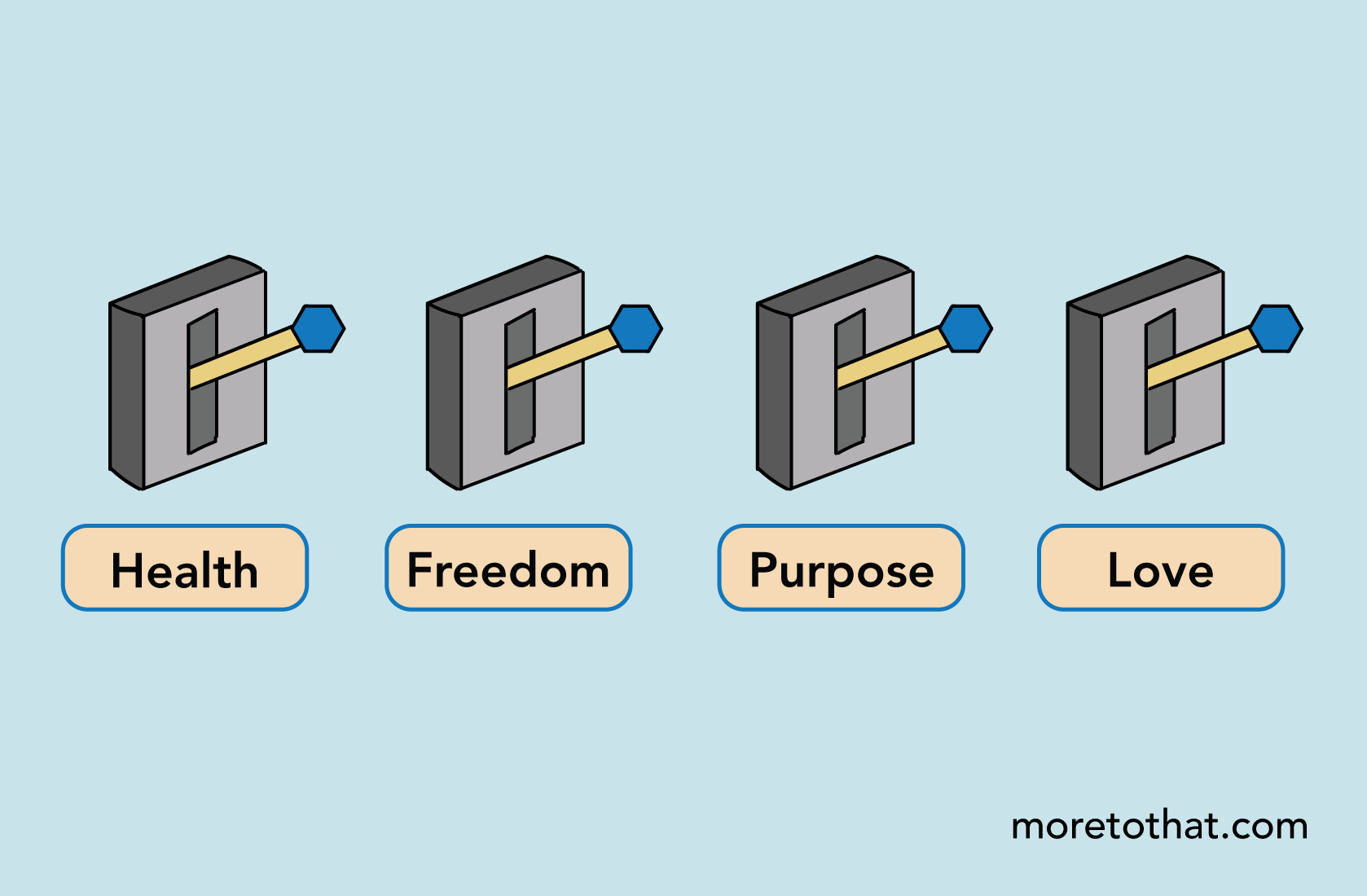

The thing about each of these desires, however, is that they are not binary, meaning that it’s not a question of fulfillment vs. non-fulfillment. While you may be tempted to believe that someone is either healthy or not, the reality is that someone is more healthy than not. Similarly, people aren’t simply free or unfree. They feel more free in some respects, and less so in others.

So when I think about the four primary desires, I view them as if they’re levers on a dashboard that indicate your overall satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) with life.

Unless you inhabit the valleys of despair or the heavens of ecstasy, all of these levers will neither be 100% down nor up. Some will be at the midpoint, others will be slightly higher or lower, but all will continually fluctuate throughout life. There are many experiences and factors that contribute to the position of these levers, but one of the tools we seek to shift them up is money.

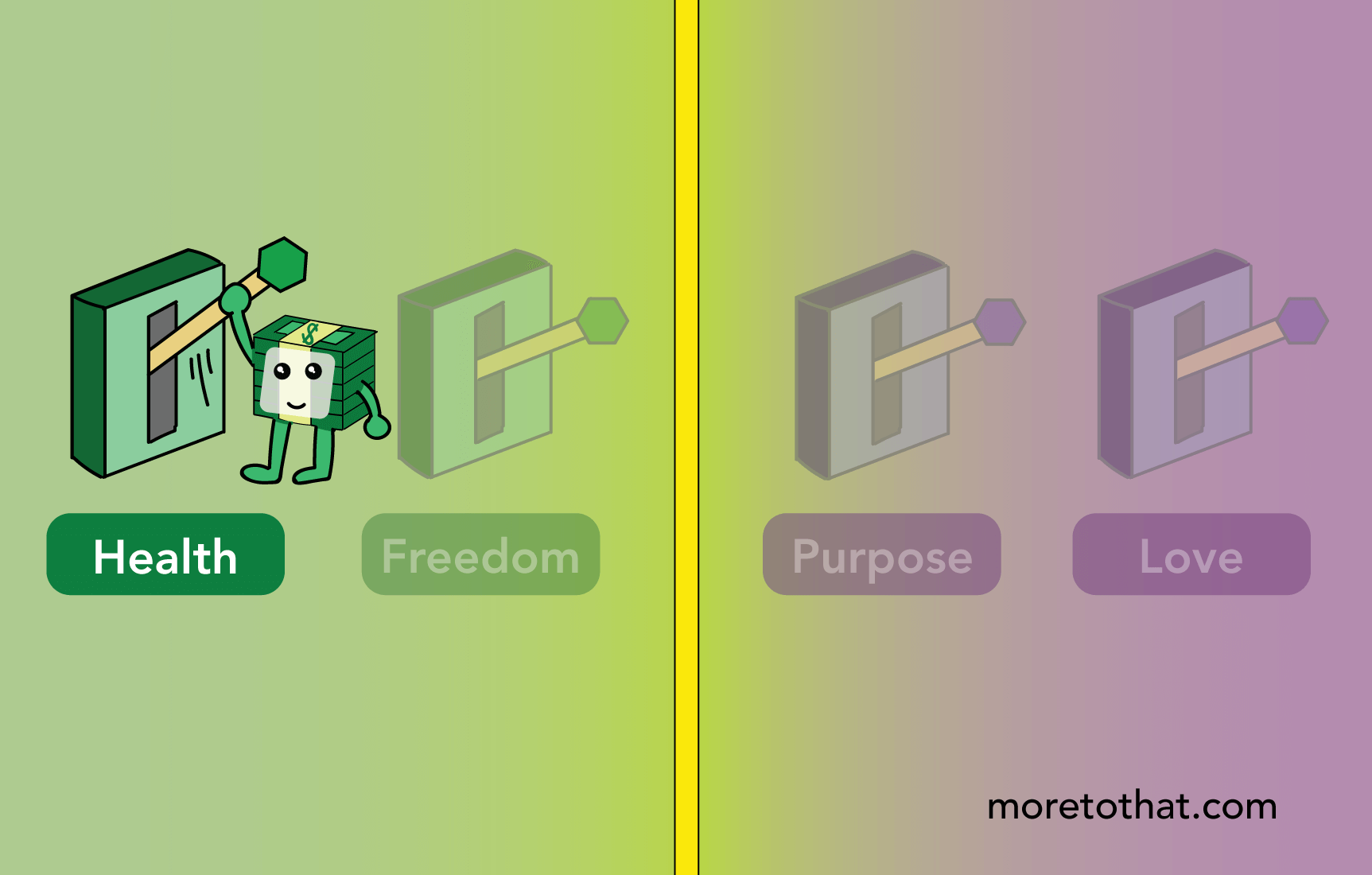

The reason why money consumes so much of our attention is because we often believe that it has the power to push all these levers up at once. Since it acts as a force multiplier of whatever values you already espouse, it’s natural to conclude that if only you had more of it, you’d be able to open up the doors required for you to put all of those values into action.

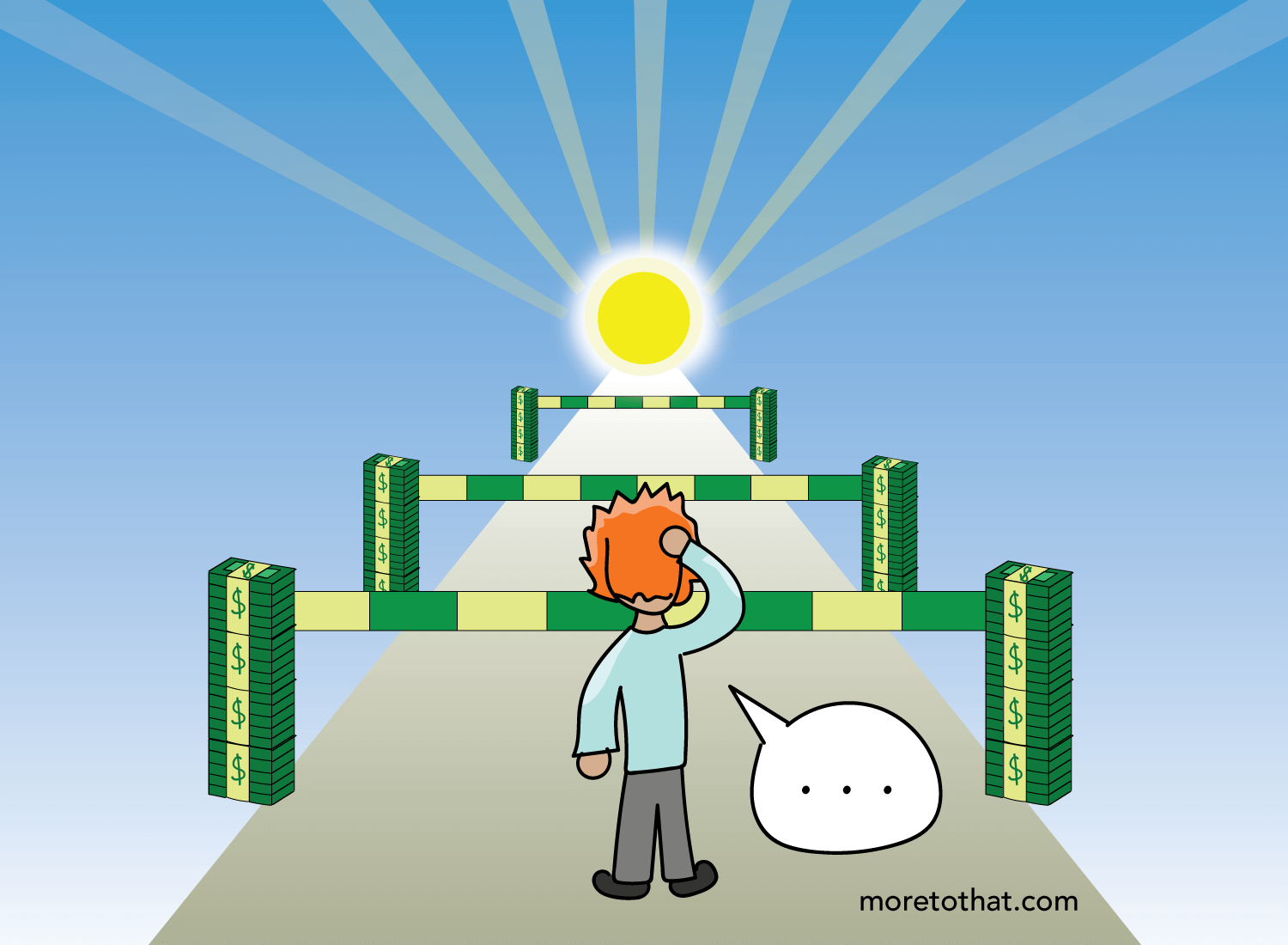

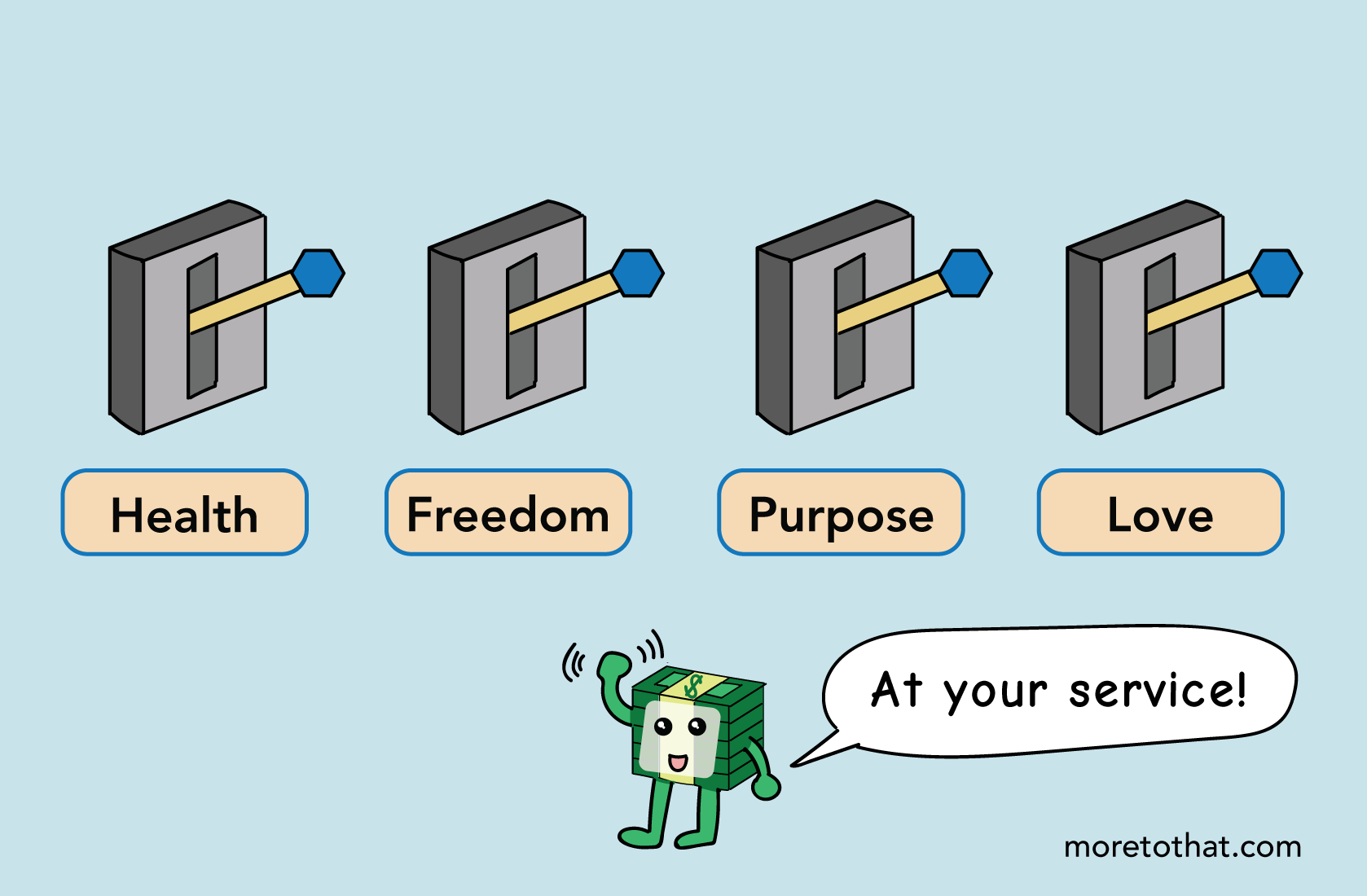

But here’s the stark reality: Money can only pull up some of the levers on this dashboard. For the areas in which it can, the pursuit of it holds importance. But for the areas in which it can’t, it must be disregarded as a solution to that domain.

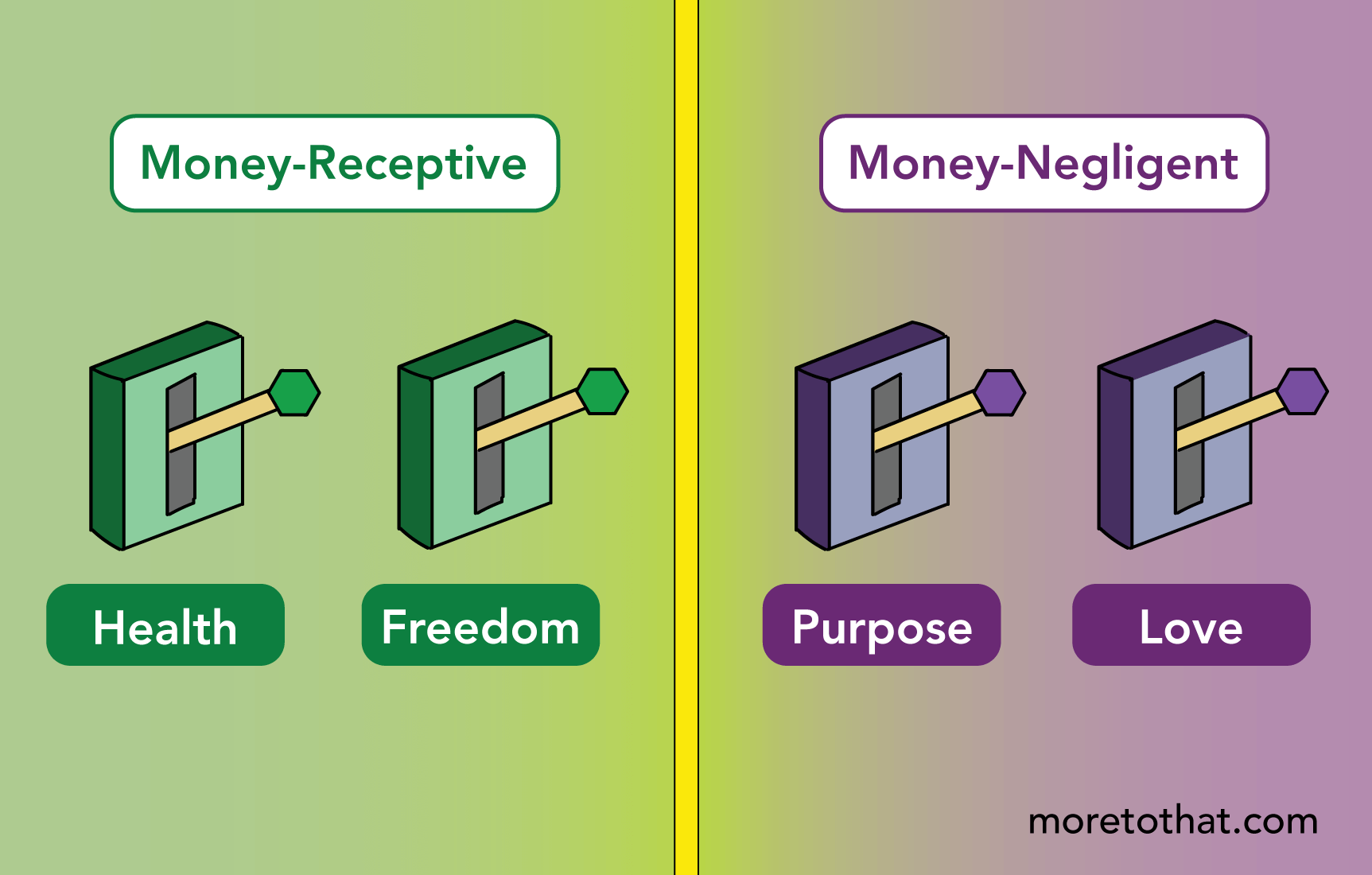

Fortunately, the dashboard we have can be easily segmented into two sections, so we can quickly see which area is which. The left-hand section is the Money-Receptive side, and the other is the Money-Negligent one:

Let’s first start with Health.

While it’s true that you can’t compensate your way into a stronger body, the reality is that money provides you with the resources that enable you to do so. If you’re in lackluster shape, you can hire a trainer to keep you accountable and join you in your path to wellness. If you need to improve your diet, you can afford to buy organic produce and various supplements. Money can accelerate the focus of your discipline, but of course, without that discipline, it’s the same as multiplying a big number by zero.

With that said, if you’re committed to improving your health in whatever way possible, then money can act as fuel to help take you to where you want to be.

Next, let’s move onto a big one: Freedom.

Freedom is a loaded word, so let’s take a moment to define it here.

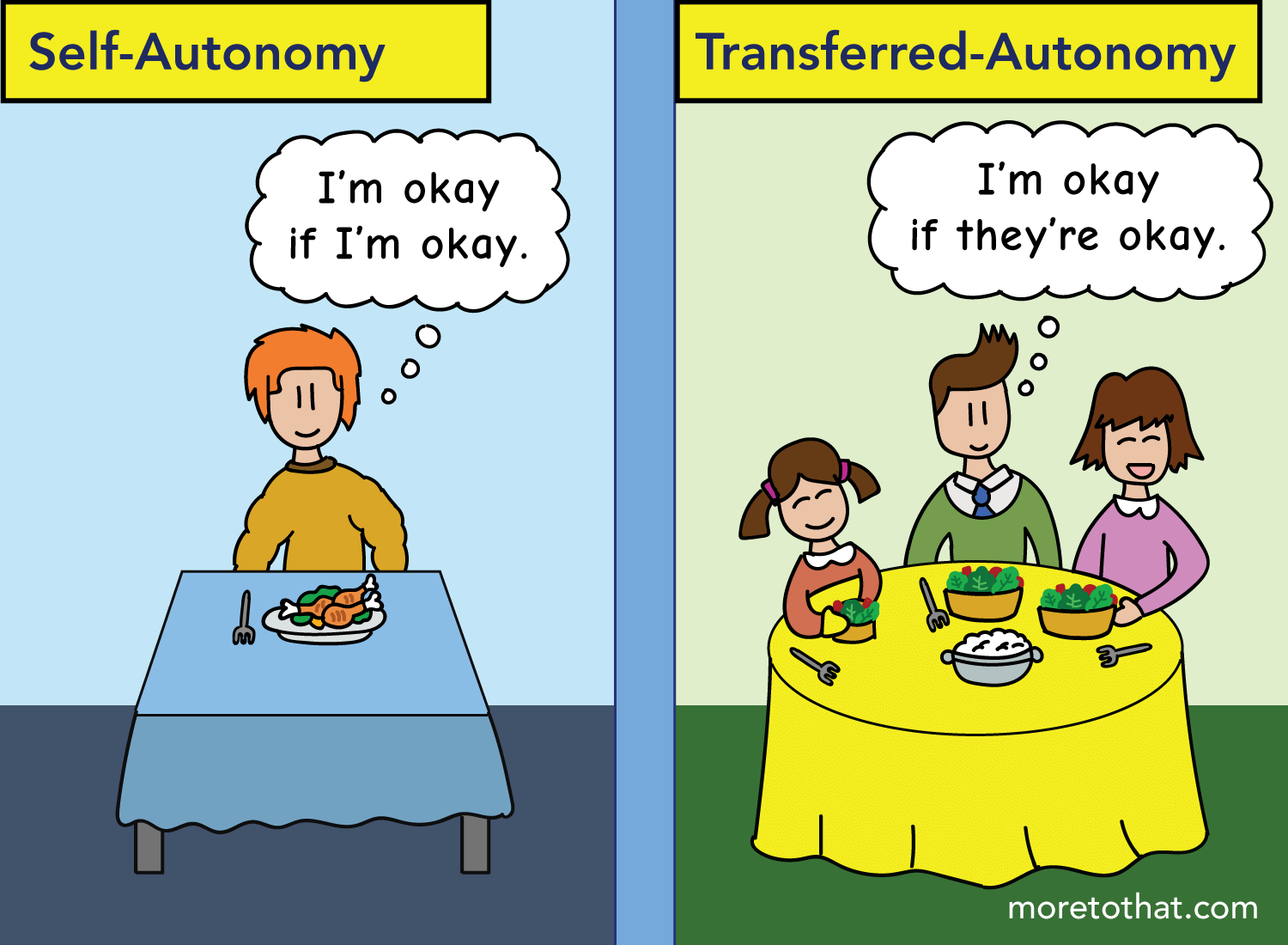

There are two main types of freedom, the first of which I refer to as self-autonomy, and the second which I refer to as transferred-autonomy.

Self-autonomy is your personal ability to do what you want, whenever you want, with whom you want. In essence, it’s freedom over your attention, and the ways in which you want to allocate it. If you have enough money, you don’t need to direct your focus to obtaining more of it, which means that you don’t need to work for someone you’d rather not work for or solve a problem you’d rather not solve. This is one of the areas in which money can push this lever in a favorable direction.2

Transferred-autonomy is an extension of self-autonomy, but for many people (especially parents), it’s even more important.

Transferred-autonomy is your ability to give a loved one the ability to do what they want, whenever they want, with whom they want. It’s when your definition of a well-lived life is also contingent upon whether you’re providing a suitable environment for a loved one to thrive. Your definition of freedom extends beyond the domain of the self, and must also encompass the freedom you help to enable in the people you love most.

From a self-autonomy perspective, you can have little money and still feel free. After all, curiosity has no price tag and the ways in which you want to express it are increasingly affordable, so a minimal lifestyle is achievable (if not sensical) with the right mindset.

But the desire for transferred-autonomy makes things tricky.

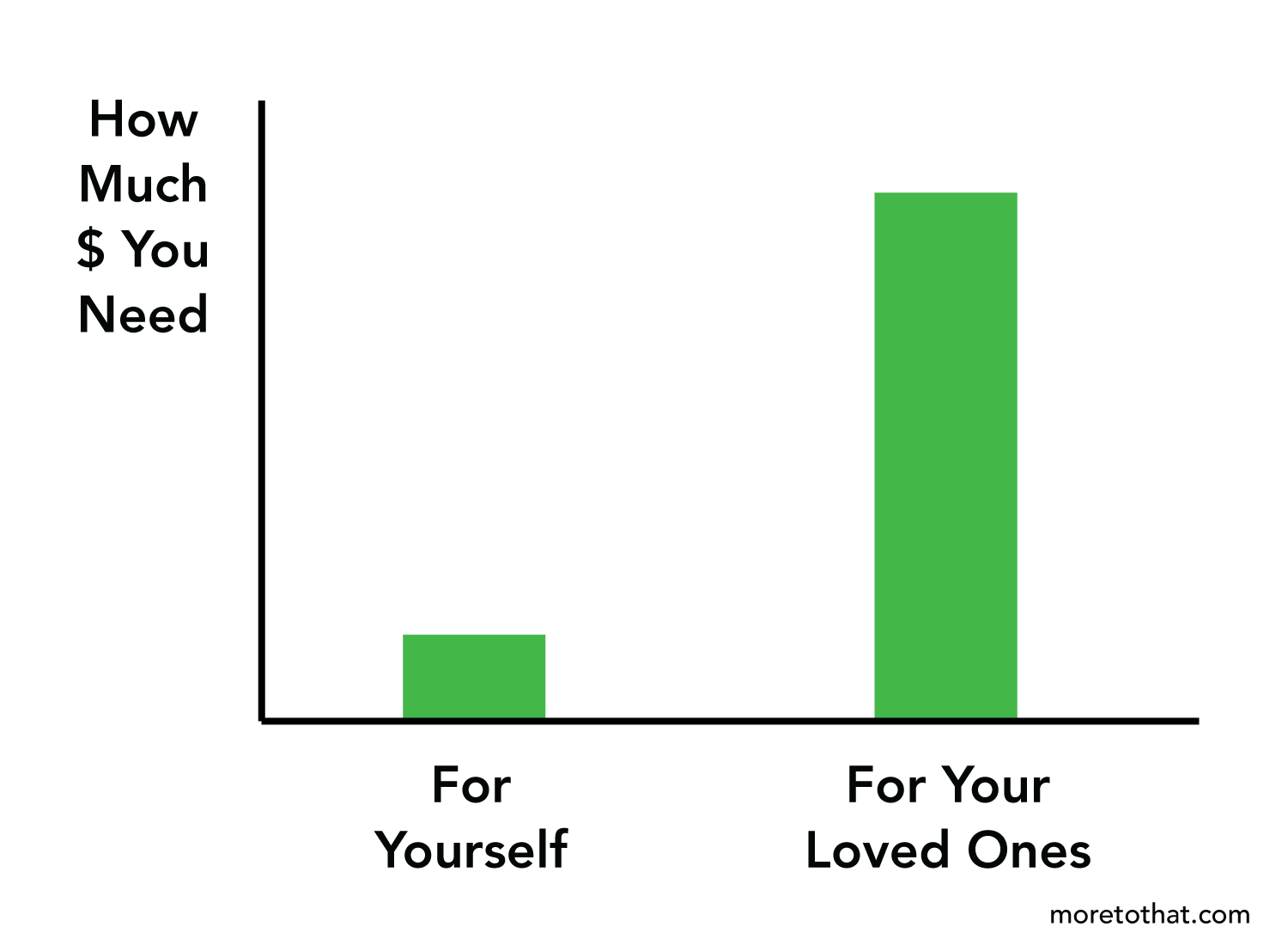

You can personally be very content with little money, but that contentment will erode if you feel like you’re not giving a loved one what they need. For example, it’s easy to live the monastic life as a single person in your 20s, but damn near impossible to do so as a 40-year-old father of three. That’s because the latter situation rests heavier on your conscience, which is something that doesn’t matter as much when you’re the sole beneficiary (or victim) of your own decisions.

When you think of your children or your elderly parents, the desire to provide is often stronger than the desire to preserve. Whatever the threshold is for your own personal needs, chances are you’ve set their standards at a higher point. So from the perspective of money, what you need for yourself can be quite minimal, but what you need to have in order to properly care for them is far greater.

In the case of John’s mom, she didn’t need much for herself, but she viscerally felt her inability to provide transferred-autonomy to John. Even if John was going to go to the Army anyway, it didn’t matter. She felt that money was the main reason why John didn’t venture into other options, and the pain of this emotion is what made her feel like a terrible mother.

The reason why Freedom is in the Money-Receptive area is because even if you personally don’t need much, you can’t help but to notice how money enables the freedom of others. You don’t need to have children to see this.3 If you’ve ever felt like you could’ve done more for somebody if only you had more money, then you understand what I mean. Freedom is the lever where money has the greatest direct impact, and is where we feel empowered when we have money, and ashamed when we don’t.

Now, if we stopped here, then it might make sense to associate your self-worth with how much you have in your bank account. Since money affords you with the resources to better health and the ability to open up options, it may be rational to conclude that money is the key to a good life.

Of course, we all know that this isn’t true, but what surprises me is how often we fail to remember that.

I’ve written before that money is a pervasive force in our minds until the day of our death. The question here is why, despite knowing that it’s not the answer. Are we simply unable to reconcile the high-level abstraction of this truth with the day-to-day reality of a transaction-based society? How can we really believe that “there’s more to life than money” when everything consequential seems to have a price tag?

Well, the answer to these questions resides in the architecture of the dashboard itself.

Much of the time, our minds occupy the Money-Receptive zone. We have to eat everyday and have a place to sleep to ensure the maintenance of our health, all of which require money. We spend much of our days working on something that culminates in a financial result that allows for freedom in attention. When it comes to the way we spend a majority of our days, we require money as the fuel to keep the engine running.

But when it comes to the question of why we’re doing all this, the interesting thing is that neither the Health nor Freedom levers can answer it. What are we staying healthy for? What is the texture of freedom we’re chasing? Why does all this matter in the first place?

Reflection often comes as an afterthought, but the far more powerful thing is to put it as a precursor to action. By thinking about the “why” before acting upon the “how,” you’re able to separate the action from the motive behind it. In this case, you’ll see that money enables you to buy the freedom you desire, but it can’t buy the reasons why you want that freedom in the first place.

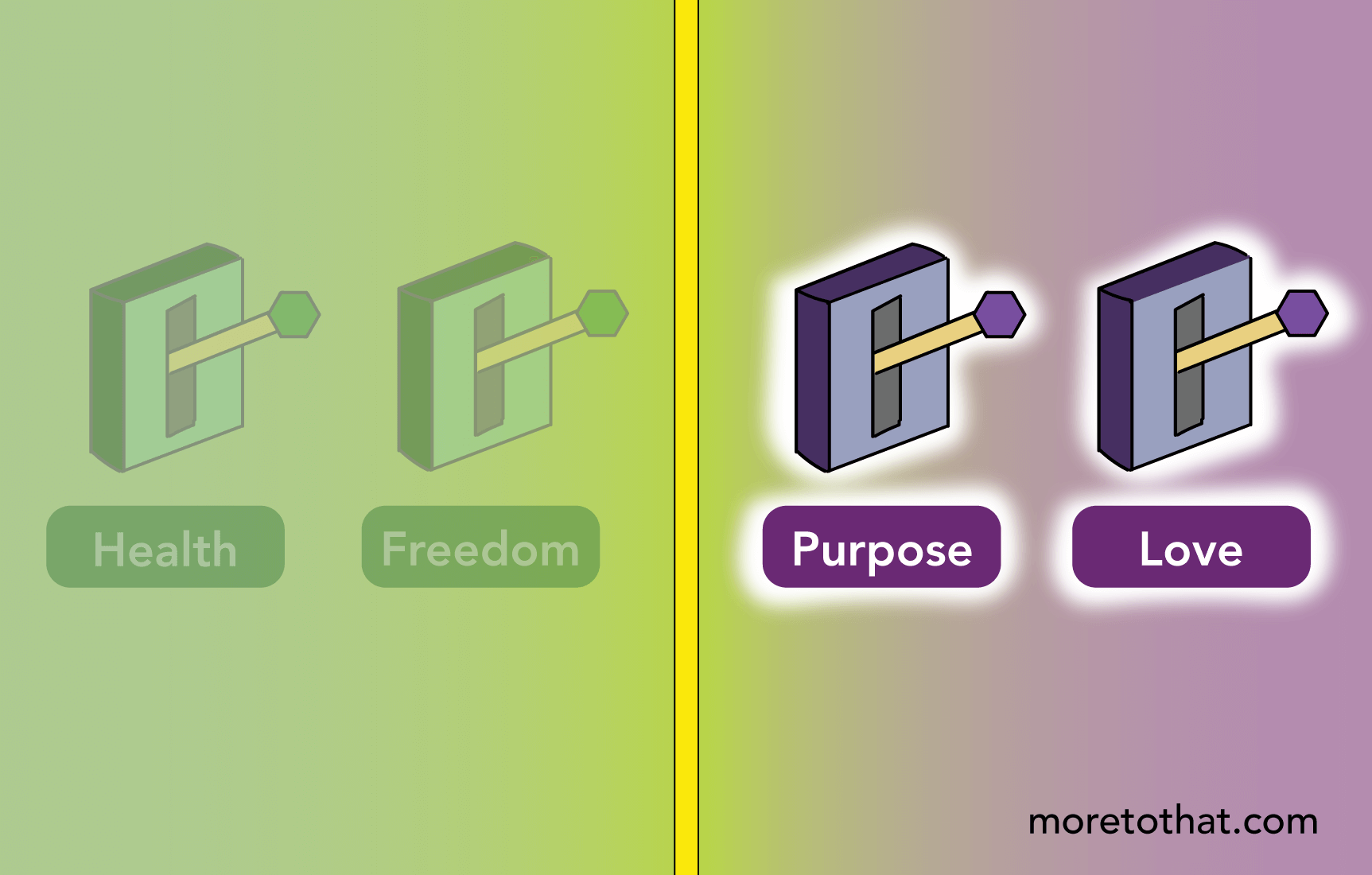

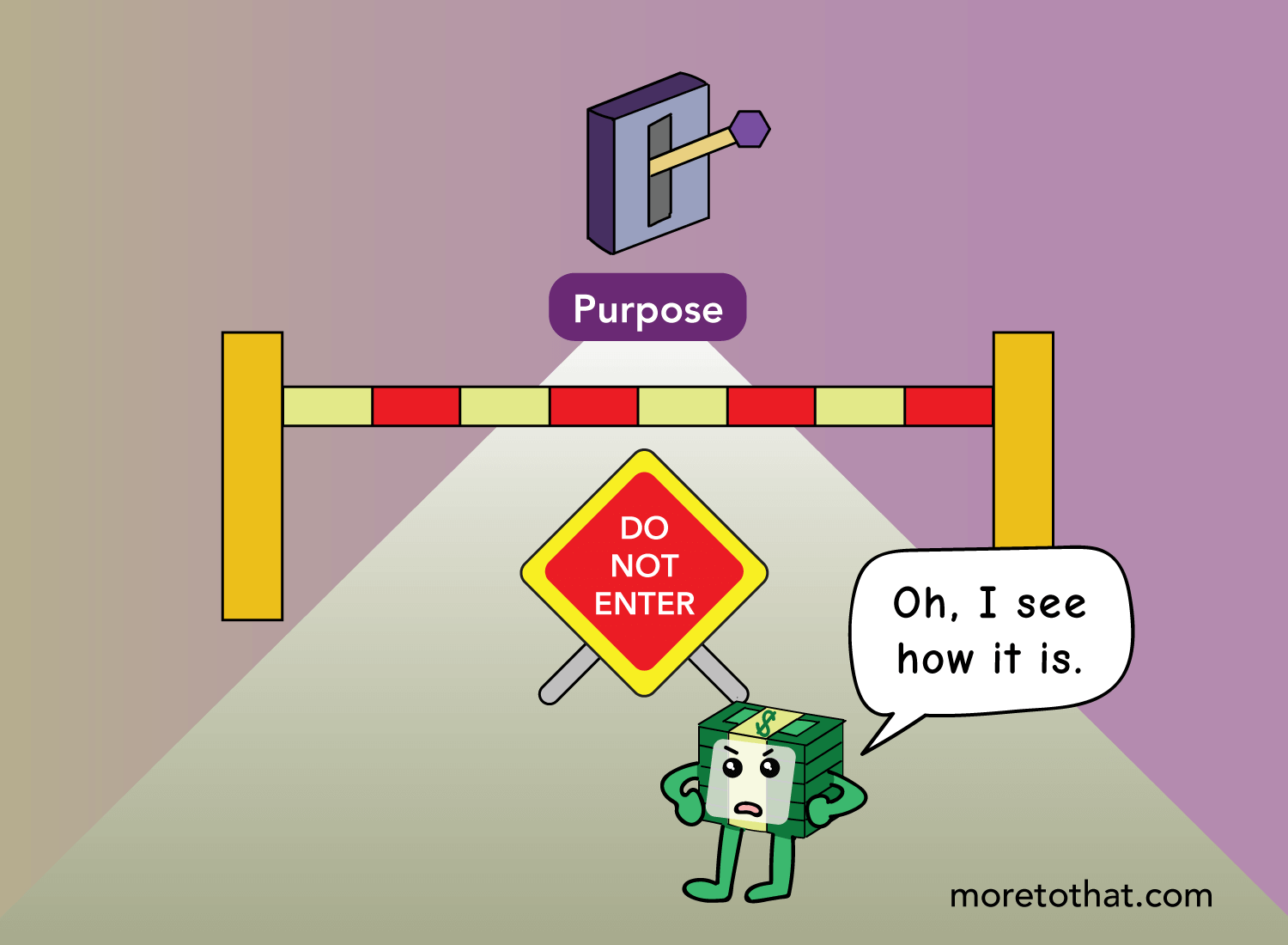

For that, we’ll have to go into the Money-Negligent zone, where money ceases to influence the movement of the levers here. That’s because these are the levers that define the core of what makes life a beautiful experience, and nothing external and uniformly defined like money can shift them.

In other words, these levers are uniquely moved by you, and how you move them are defined by the unique conditions in which you live your life.

Let’s start with the Purpose lever.

Some may argue that this lever should be in the Money-Receptive area, given that money provides the ability to explore your options and discover the endeavor that suits your curiosities. That if you weren’t stuck in a dead-end job just to make money, then you’d have the freedom to explore your potential.

But as the prior sentence indicates, this claim is a justification for freedom, not purpose. And while the words may seem interchangeable at first glance, if you dig a bit deeper, you’ll see that they’re anything but synonymous.

Let’s take a moment to clearly see this distinction.

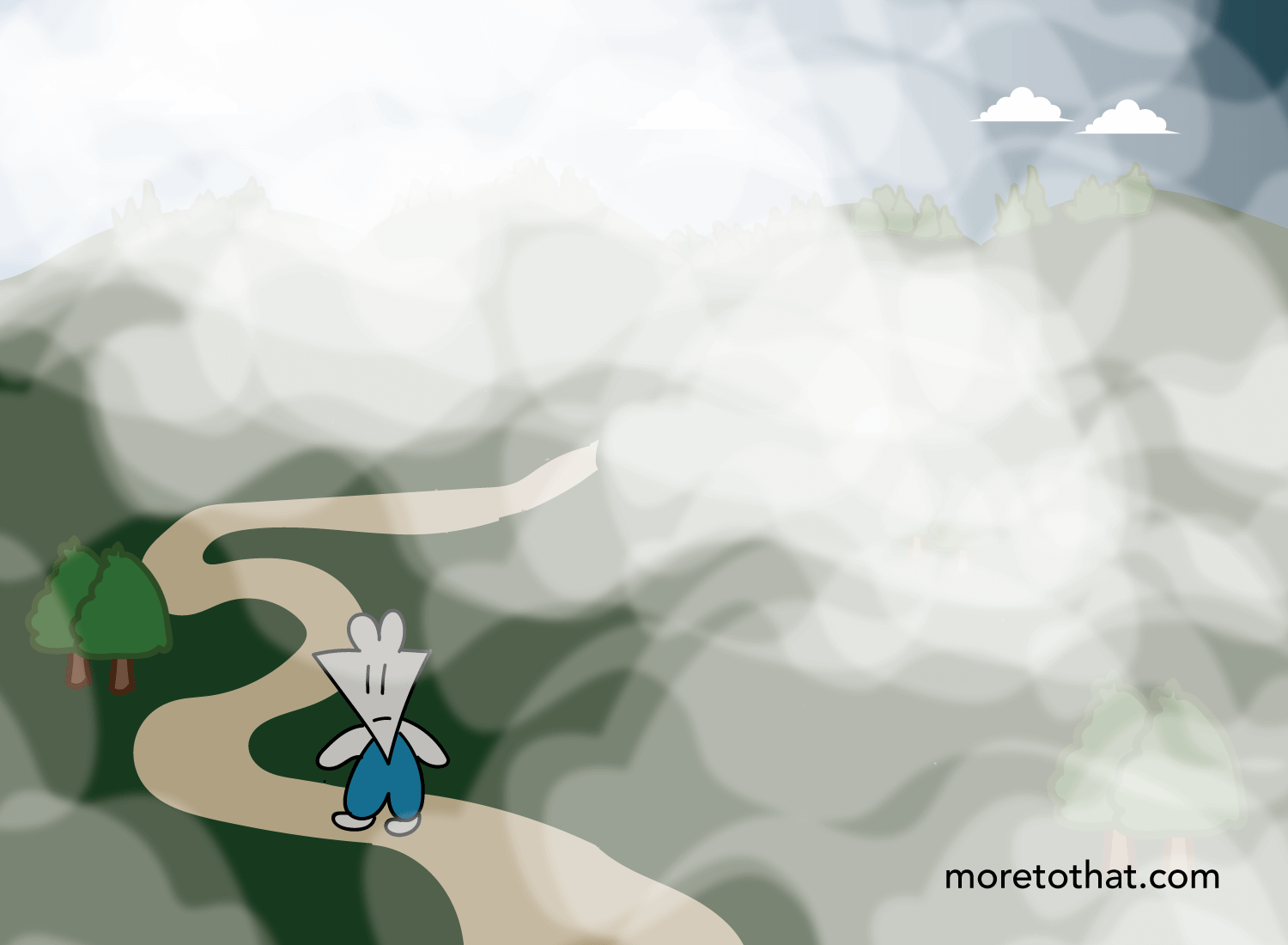

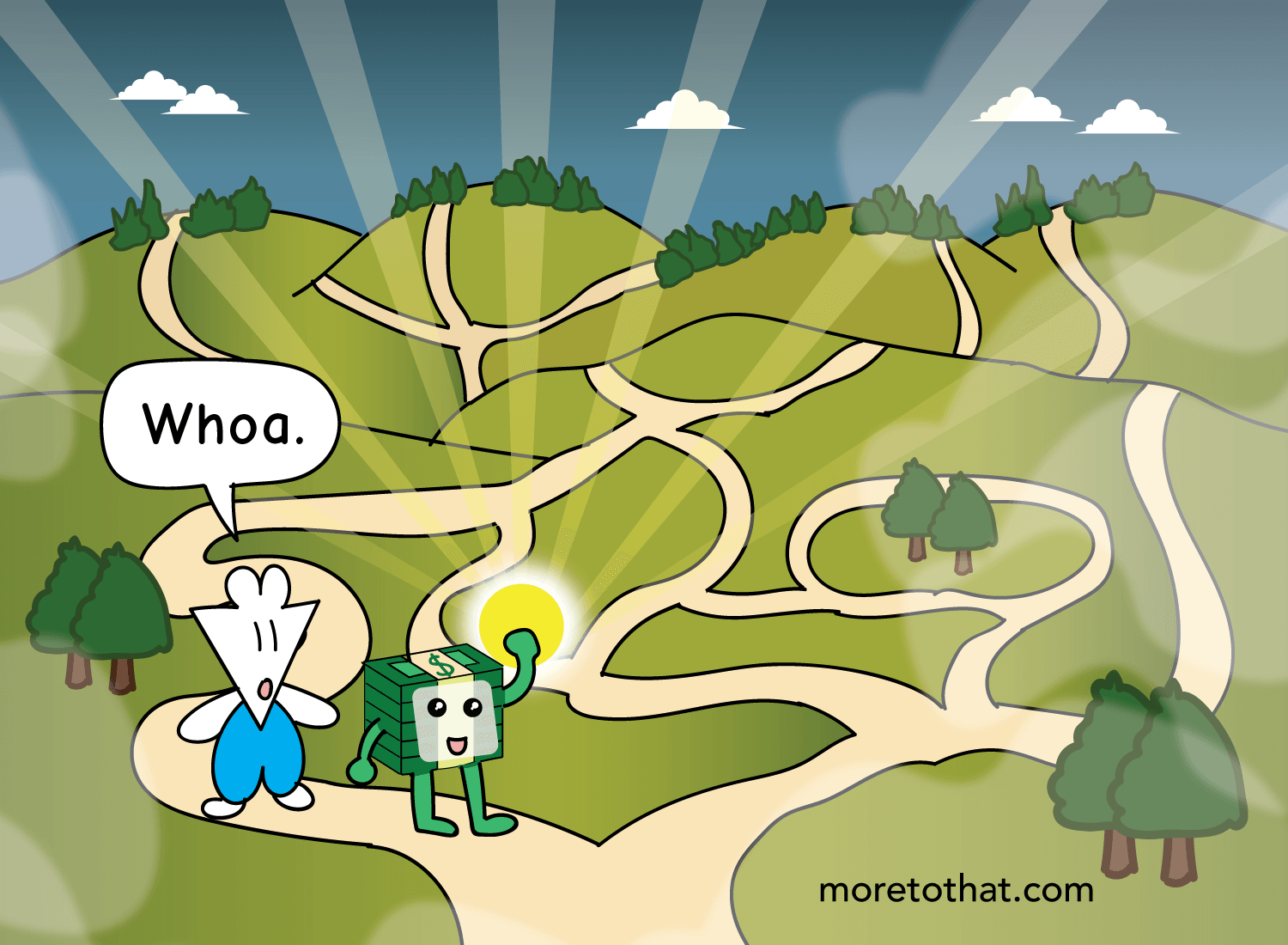

Imagine that you’re on a path, surveying a landscape that’s obscured in fog:

Freedom is the ability to see that the path you’re on isn’t the only one available to you. That there are other ways you could spend your time, and that there are many other paths out there that can be more fruitful.

Introspection can be a gateway to this kind of freedom, but the more immediate tool that can achieve this is money. As we discussed earlier, money has the keen ability to open up doors that were once closed, so it can act as the light that cuts through the fog to reveal the paths lying below.

With money, you can say “no” to pointless jobs and give yourself permission to explore what else there is. You can give yourself some time to explore what really makes you curious, and what avenues there are to express it.

But what money can’t provide are the reasons why your specific curiosities exist in the first place.

This is where purpose comes in.

The rationalist in me says that purpose arises as a response to being good at something. That when you’re directing your energy into a worthwhile endeavor and are rewarded for it, that’s when purpose takes hold.

But the esoteric in me says that purpose is inherent in all of us, and that our curiosities exist without justification. That there are modes of expression that each of us are meant to discover, all without the need for validation or approval from others. That we all have a latent potential we’re meant to fulfill, and our desire to fulfill it must come purely from within.

It’s safe to say that the esoteric in me is winning at the moment.

The reason why purpose exists outside the bounds of money is because no one’s purpose on this earth is to make money. This is simply never the case, even if on the surface it may seem otherwise. While someone may diligently pursue wealth, they’re not doing it because a deposit of million dollars fulfills their potential. No, what’s actually fulfilling their potential is the cultivation of skill sets and the overcoming of challenges that are required to make that million dollars. The purpose underlying the pursuit is driven by something internal, while the money is a nice fist bump from the outside for their efforts.

Bob Marley (supposedly) said that “some people are so poor, all they have is money.” What he meant was that there are people that mistake the pursuit of wealth for their purpose, and when they realize that they’ve conflated the two, they understand that they’ve missed the point of why life is so worthwhile in the first place.

This is why purpose must be discovered without the promise of incentives or monetary rewards. It can only come from conducting an honest audit of what makes you feel wonderment (i.e. childlike curiosity) or a sense of duty (i.e. parental responsibility), and then directing your attention to making the most of those endeavors.

The sense of self-worth that can be derived from purpose is free from money’s clutches, so keep this in mind whenever you feel discouraged by how much you have. Money is simply not a variable here, and the knowledge of that goes a long way.

And now, let’s discuss the final lever: Love.

If there’s one lever that transcends all the others, it’s this one. You can be the healthiest person on the planet, but if you love no one, what’s all that vitality for? You can be free to do whatever you want, but if there’s no one to spend that time with, what’s the point? Is it even possible to feel a sense of purpose in your days if you believe that you’re loved by no one?

Ultimately, love is the thing that matters most, but it’s often overlooked and disregarded as a cheesy emotion. In the minds of many, skepticism signals intelligence, whereas love signals naivete. After all, you garner respect by sounding the alarm on humanity’s problems, and not by pointing to love as the answer to them.

This is precisely why love is taken for granted. Even if love is felt between you and another person (be it a friend, partner, family member, whomever), it’s often left unarticulated because saying “I love you” means that you’re fine with seeming naive and aloof. And if this fear goes on long enough, you’ll feel that the best way to express your love will be through ways that act as surrogates for it.

Earlier, I talked about transferred-autonomy, and how we use money as a vehicle to provide freedom to our loved ones. While this may be one way to express your love, it’s crucial to realize that it’s not a stand-in for it. It’s amazing how often this mistake is made, causing so much needless suffering along the way.

You can pay for your child’s fantastic education, buy them a big house, and give them a fat brokerage account, but if they don’t feel your presence, none of this matters. While you can use money to open up opportunities for your loved ones, the opening of all these doors is meaningless if you don’t walk through them together. Love is shared through continuous presence, affirmation, and affection. Any attempt to use money as substitutes for these three things will ultimately be denied, or even held against you.

The greatest thing money can buy is freedom, but that pales in comparison to love, which is the greatest thing that nothing can buy.

When I think back on John’s mom, the reason that story made me so sad was because I knew how high her Love lever rested. She was always there for her sons and they always felt her presence, despite her relentless schedule of working 2 physically demanding jobs. Not only did she love them with all her heart, she was loved just as much.

But despite this, she still felt like she sold her son on the day she received that check. Her inability to shift the Freedom lever to a higher position made her feel unworthy as a mother, and that was what pained me most. Knowing that someone with her heart can feel like a criminal was such a saddening realization for me.

Sometimes I like to think that if I showed John’s mom her dashboard and the placement of her levers, that may have helped to relieve some of her burden. She would’ve seen that the Freedom lever may not have been as high as she wanted, but that the levers of Purpose and Love were pulled up in a way that highlighted how amazing of a woman she was. And that when it came to one’s sense of self-worth, no single lever defines it all; in fact, it’s generally the levers in the Money-Negligent area that indicate the direction of meaning in life.

But most likely, this would all sound like gibberish to her, and that’s fine too. Trying to untangle the complexities of money and self-worth is no easy feat, but the intention behind it is simple. The overall point is that it hurts knowing that money can make us feel inadequate as human beings, when the truth is something entirely different.

If we can zoom out of any individual lever and take a holistic view of what makes us who we are, then we’ll see that money is just one character in the theater of life. That it can influence the direction of many things we care about, but not the things we care about most. That it’s a significant character in this story, but just a character nonetheless.

Because in the end, seeing that distinction makes all the difference.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

By defining Enough, you give your Purpose and Love levers the attention they deserve:

By understanding that you’re safe, you quell your fears of financial ruin:

The Survival Instinct of Money

By giving money its purpose, you ensure that it serves you, and not the other way around: