The Information Lifecycle: How Three Filters Shape the Mind

Let’s start this post off with a question:

Did you know that the obesity rate in South Korea is 4%?

Perhaps you knew this, perhaps you didn’t. But upon reading that, it may have triggered a bunch of other thoughts that weren’t even close to entering your mind before you started this post.

This dispersion of thought is immediate, so it’s natural to brush it off as an instinctive response to a little-known fact. However, if we slow down this process and break it down, it will reveal something interesting about the nature of information.

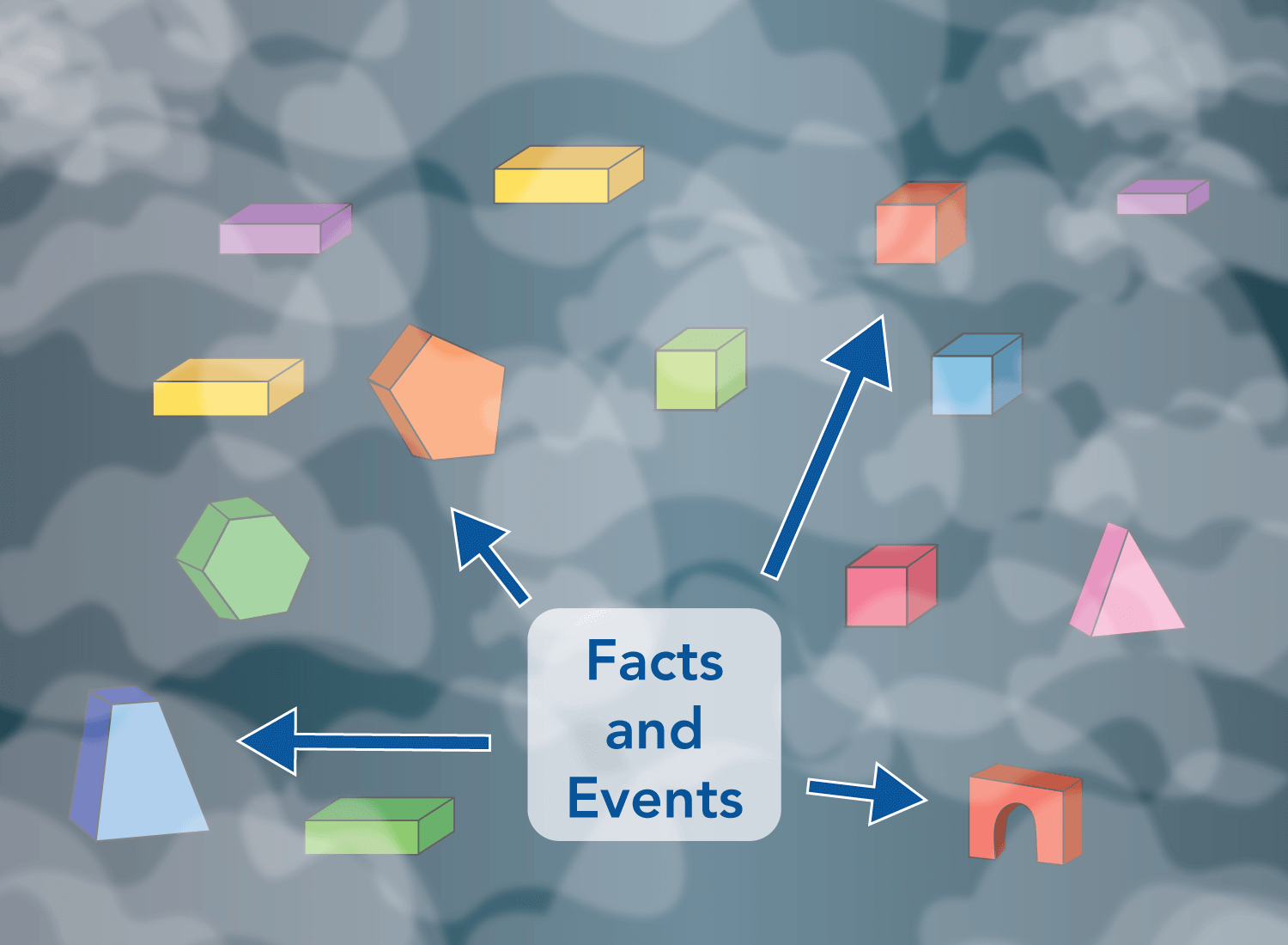

Let’s first start with the fact that you weren’t thinking about Korean obesity rates at all before you started reading this post.1 This is what it’s like for almost every fact or event about this world. There’s simply too much going on, and since attention is a zero-sum game, we are mostly oblivious to every little thing that is happening everywhere.

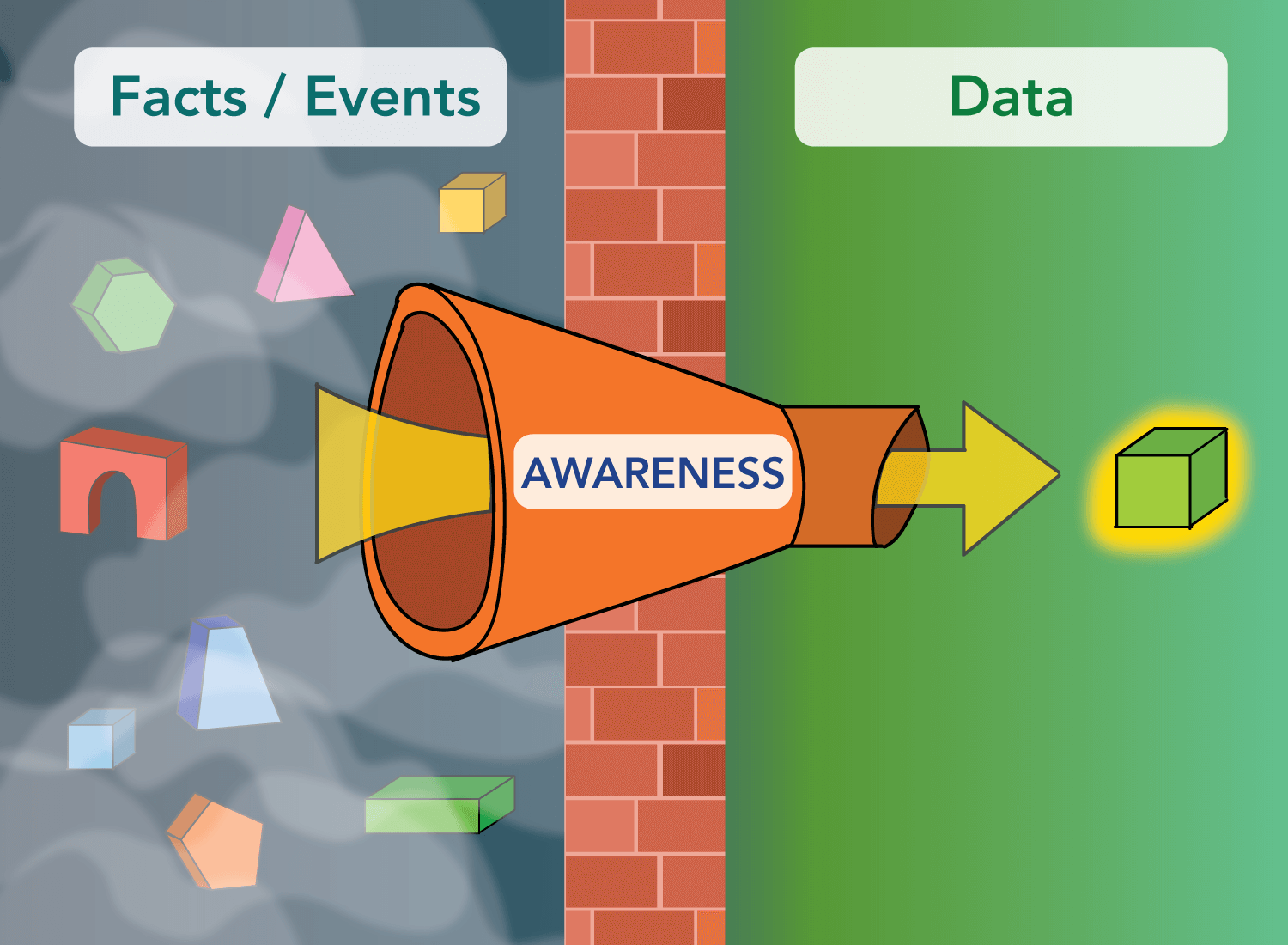

But something happened once I told you about that fact. You were made aware of its existence, which brought it out of the fog of obscurity and into your field of attention. Passing through this filter of awareness allowed that fact to cease being an unknown tidbit of the world, and was converted into a packet of data that you can now interact with.

The moment an unknown fact passes through awareness, it becomes data, not information. This distinction is important. Data does not have to be processed, whereas information does.

For example, if you show me all the code being used at Facebook, I wouldn’t be able to interact with it in any way. Since my coding knowledge is limited (to put it nicely), it would be mere data to me. Despite all the power being revealed, I wouldn’t know what the hell to do with it.

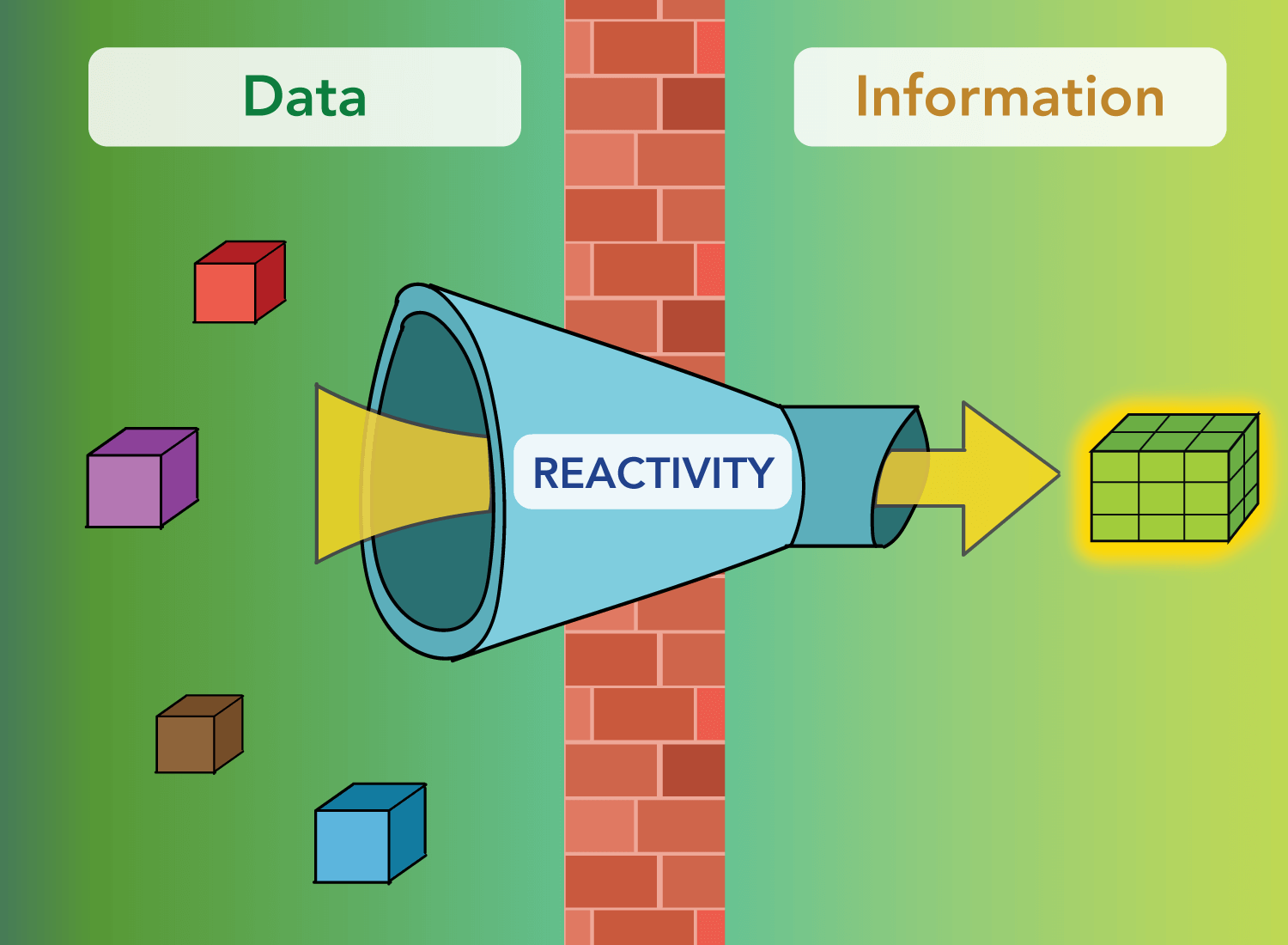

The utility of data lies in our ability to react to it. If we have either the intellectual or emotional capacity to process it, only then does it becomes information.

In our Facebook example, that code would be information to an experienced engineer. In our Korean obesity rate example, that would be information to anyone with an opinion. Even the person that touted indifference has processed that data to then assert that he doesn’t give a shit.

Whenever we point to “information abundance,” what we are really saying is that we have “endless opportunities to react to data.” Whatever we want to engage with and process will be there at a moment’s notice. Whether it’s a 30-minute TV news segment or a never-ending Twitter feed, we will be able to see what we want to see, and toss out the things that we find questionable.

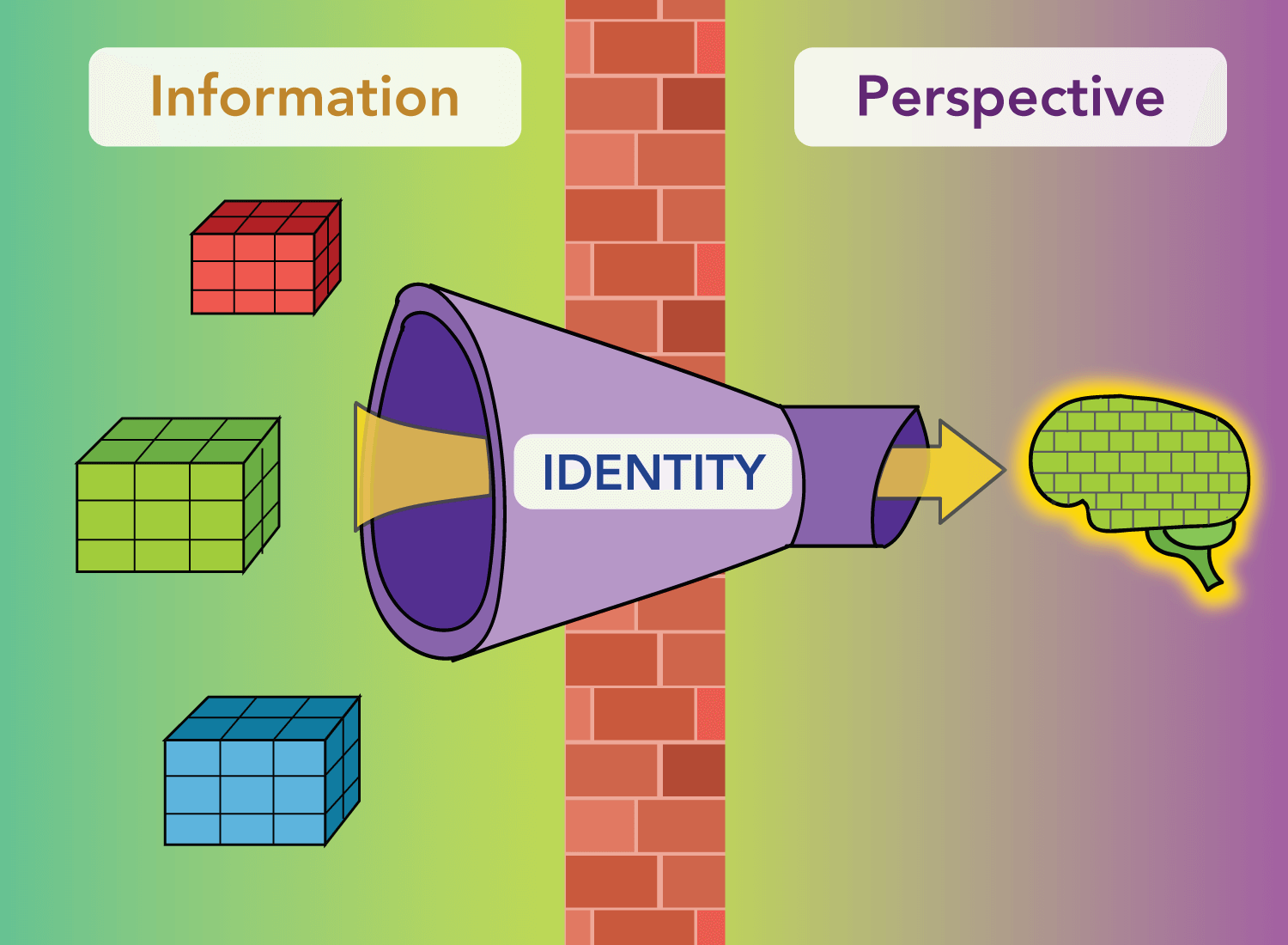

This selection mechanism is the final stage of the information lifecycle. There are some pieces of information that resonate so deeply that we allow it to shape our perspective of the world.

And the filter that allows this to happen is shaped by the thing we hold onto most dearly:

Our identities.

There are some people that will take that fact about the low obesity rate in Korea, and will go into a rabbit hole about how that came to be. Perhaps they’re deeply curious about nutrition, and want to understand how their diet could improve based on what the Koreans eat. Or maybe they are researchers that want to study the longevity of certain populations throughout the world.

Regardless of what the reason is, there are some people that will identify so strongly with what that piece of information could reveal, and will absorb it into their world view. Of course, this is most prevalent in the political realm today, but it applies just as much to any other area of interest as well. Whenever we highlight a passage in a book or make an effort to shift our behavior based on something we hear or read, this is the result of an identity screaming out that a piece of information will be useful.

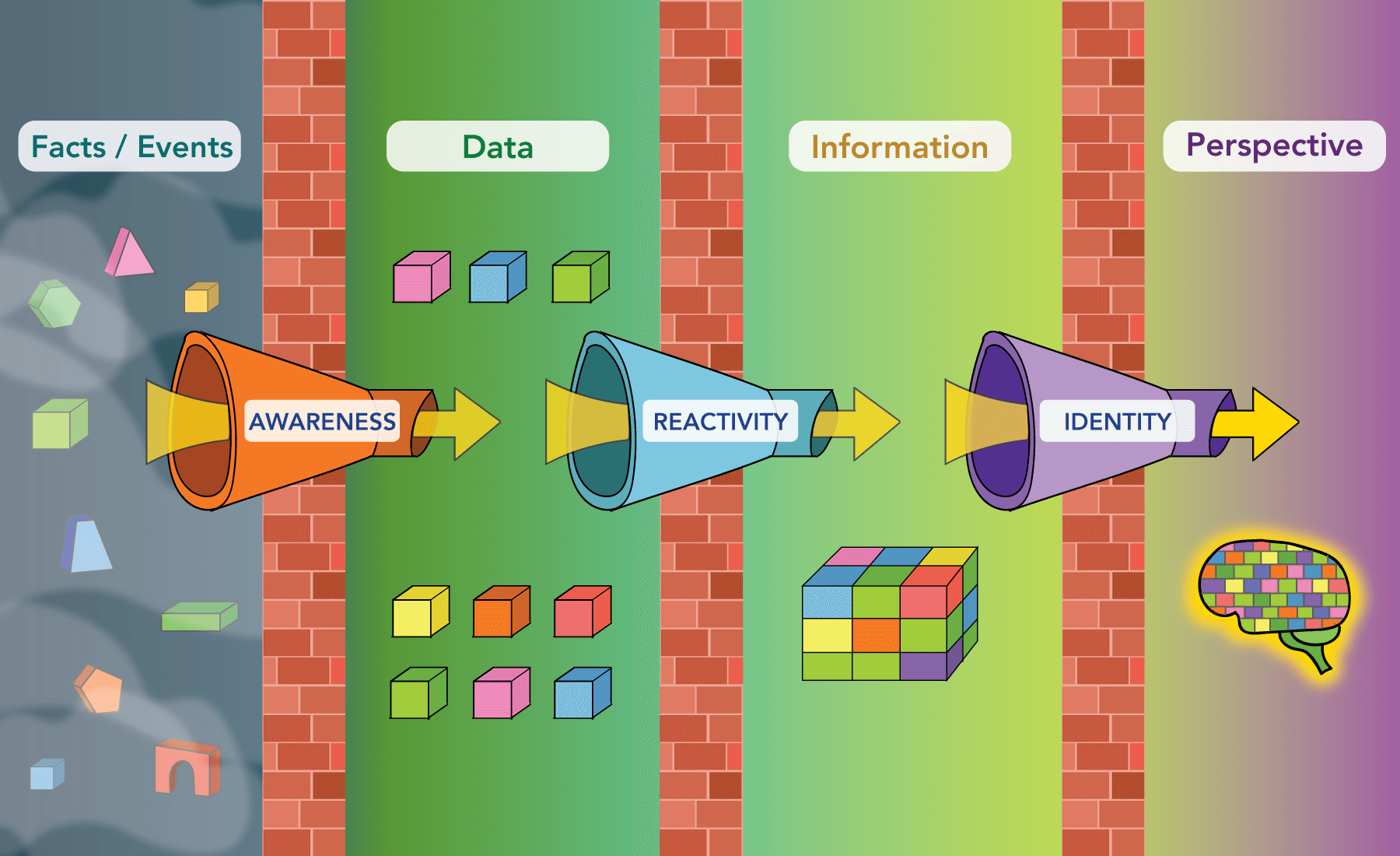

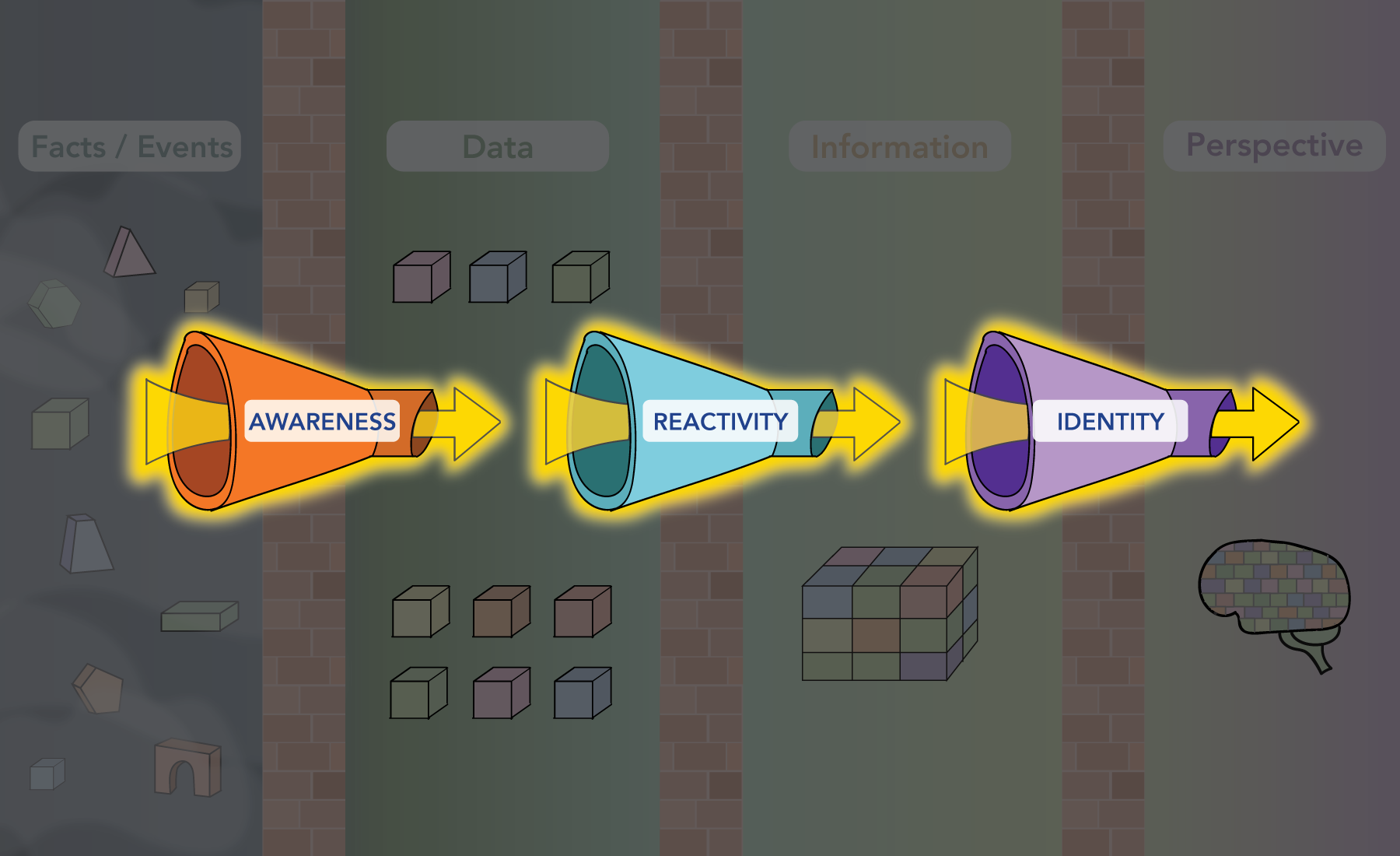

This whole process of previously unknown facts eventually shaping one’s perspective is what I call the information lifecycle:

The interesting thing about this process is that it rarely feels segmented in this way. Whenever we come into contact with some objective fact or event, it moves so quickly across these stages that it’s essentially unnoticeable. When we read something in the news, we don’t ponder whether this is data or information, and whether or not we want it to influence our outlook on a given subject. All this happens instantaneously, as if the transmission of data and the processing of it occur simultaneously.

The truth, however, is that these are independent events, and the speed in which the process moves is determined by the three filters that live in between each one:

These three bottlenecks determine how we interact with the details of the world. And by understanding how each one operates, we can realize what areas are reliable, and which ones are riddled with blind spots.

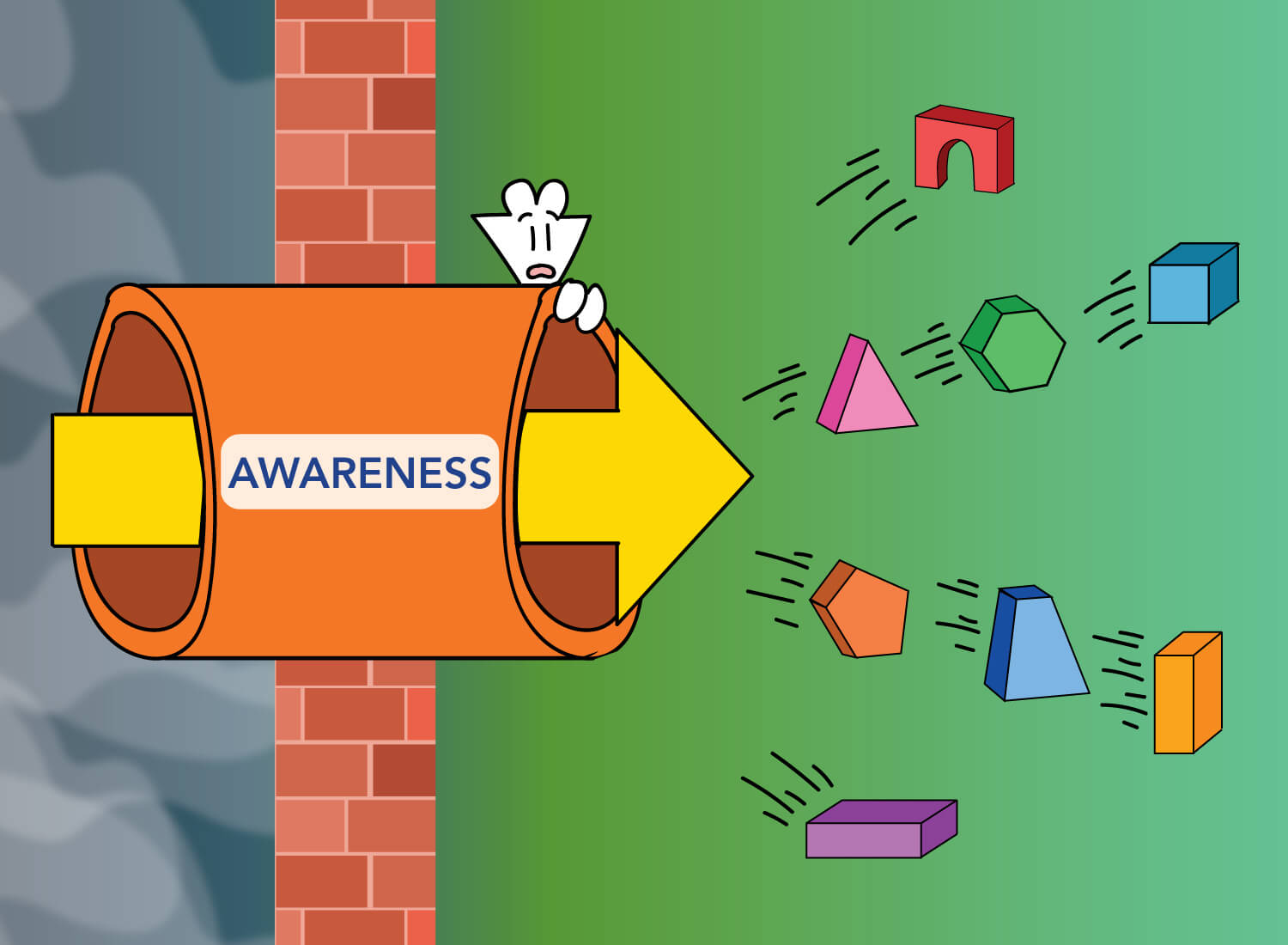

The first filter is awareness. Awareness could be as simple as noticing a freshly bloomed flower on your everyday walk, or as complex as coming across a philosophical concept that you’ve never heard of before. Regardless of which end of the spectrum your awareness touches, the whole of it is governed by a phenomenon that we’ve covered time and time again:

Curiosity.

Curiosity is the starting point of any information lifecycle. It’s the first filter we put the world through, as wonderment is the prerequisite to any search for knowledge. Whether it’s opening up a new book, scrolling through Twitter, or hopping onto a news site, each of these actions are made possible by that little tug on your mind saying, “I wonder what’s going on here…”

However, there are shades to curiosity that give it a quality of its own. At its purest, we are open to taking in whatever we don’t know enough about, widening its range so that all kinds of topics and opinions float on in.

At its most restrictive, we are only curious about what we already know, and what we already believe. Much of what filters through is vetted by a static outlook, which homogenizes all of the facts and details that come to our attention:

Most likely, you are somewhere in between the two. While we would love to know everything there is to know, our personal interests put selection pressure on the ideas that make it through this filter. We have a bias toward interacting with the things we care about, and filtering out the rest as noise. But of course, if this becomes too lopsided, this leads to echo chambers and all the other crimes against humility.

It’s a delicate balance, but generally, the more you can open this filter up, the better.

Whatever passes through becomes data, but in order for that to be processed as information, it must pass through the filter of reactivity.

As I said earlier, data means nothing if you can’t react to it. An influential book is meaningless if you can’t read it. The next great discovery in physics won’t register to a person who can’t understand its implications.

What allows one to adjust the filter of reactivity is the strength of their capabilities.

Data becomes information only when you have the cognitive capacity to interpret it as such. I can’t interact with code until I learn to code. I can’t put bricks together until I learn construction. The more perplexed I am about the data I’m made aware of, the more evident it is that I don’t have the abilities to convert it into something useful.

I’m reminded of this whenever I sit down with a book that’s difficult to understand. If I feel that the author is saying something interesting but I can’t quite grasp what it is, that means I have to keep wrestling with topics of this nature so I can strengthen my ability to comprehend it.

Interpreting information has less to do with curiosity, and more to do with diligence. Curiosity was the force that brought me to the book, but diligence is what will make that book a useful source of knowledge. Whenever a trove of data is present but I’m unsure of how to convert it into treasure, I know that I have to do some heavy lifting to unlock its utility.

Once that information is processed, we then have the option to incorporate it into our worldview, or discard it altogether. This is decided by the final bottleneck: the filter of identity.

To define identity would require a 5,000-word post of its own, but at its simplest, identity is the collection of beliefs, ideas, and truths you hold to position yourself within the world. No matter how independent you think you are, identity is always constructed in relationship to something else that exists alongside you. If you are a writer, that is because someone else’s writings influenced you, or the culture you’re a part of is receptive to that form of expression. If you are a liberal, this is because you’re part of a system where liberal and conservative values have dominated the conversation, and one is more compelling to you than the other.

We all have so many relationships with different ideas in this world, and seeing that there are billions of minds living today, this can make for a confusing existence. To alleviate this, we’ve created the notion of identity, which helps to categorize our world views so we can better understand where we stand in relation to others.

This categorization, however, creates a fundamental tension:

Identities organize the familiar, but divide the unfamiliar. The more we love the idea of “us,” the more we hate the idea of “them.”

And nowhere is this more apparent than in the way we handle information.

By definition, information is something we react to, and identity is what will determine the scope of said reaction. For example, if you come into contact with something you disagree with, your identity filter will shut off immediately, preventing that information from getting anywhere near your perspective.

But if that information holds a similar character as your identity, then the filter will open wide, allowing it to come in and pad a perspective that already looks just like it.

Similar to the reactivity filter, the best place to set your identity filter will be somewhere between the two poles. You don’t want to let any truly repulsive ideas in, but you also don’t want to soak in everything that confirms what you already believe.

The greatest riddle of the 21st century is to learn how to accomplish this. As technology makes it easier for you to find your tribe, it also makes it just as easy to dismiss those who aren’t in it. This seems inevitable, given that any tool designed to connect people is done primarily in the name of like-mindedness.2

Perhaps the only way we could break away from this is to free ourselves from the notion of identity as much as possible. Krishnamurti calls this “freedom from conditioning,” where we are able to let go of all the societal influences that have shaped and categorized us into certain roles. That you’re not defined by the relationships you have with other preexisting cultural ideas and norms. That underneath all the layers of identities and responsibilities is simply a being that lives and creates.

The less we need to rely on our identities to make sense of information, the more we can learn about the world, and uncover our true place within it.

Identity is often seen as the root cause of our information biases, but in reality, it is just one filter in a greater lifecycle.

Without cultivating curiosity, the awareness filter remains closed to any facts in the first place.

Without updating our capabilities, we can’t react to whatever data we discover.

And without letting go of identity, no amount of information will ever shift our perspective.

Information feels like it flows directly into our minds, but in reality, it moves through each of these stages, all of which are governed by their respective bottlenecks. By being aware of where we stand at any given moment, we will know what filters need to be adjusted, and which are flowing in their optimal state.

Updating our model of the world is never easy, but breaking the process down makes it manageable.

Step by step. One filter at a time.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Big identity changes start with one small act:

The Small Things Are Big Windows Into Who You Are

No matter how much you know, it’s all meaningless if you don’t apply it:

The Release Ratio: How to Make Use of Everything You Know

Be open to new perspectives, but beware of anyone trying to change your values: