Self-Help and the Smuggling of Values

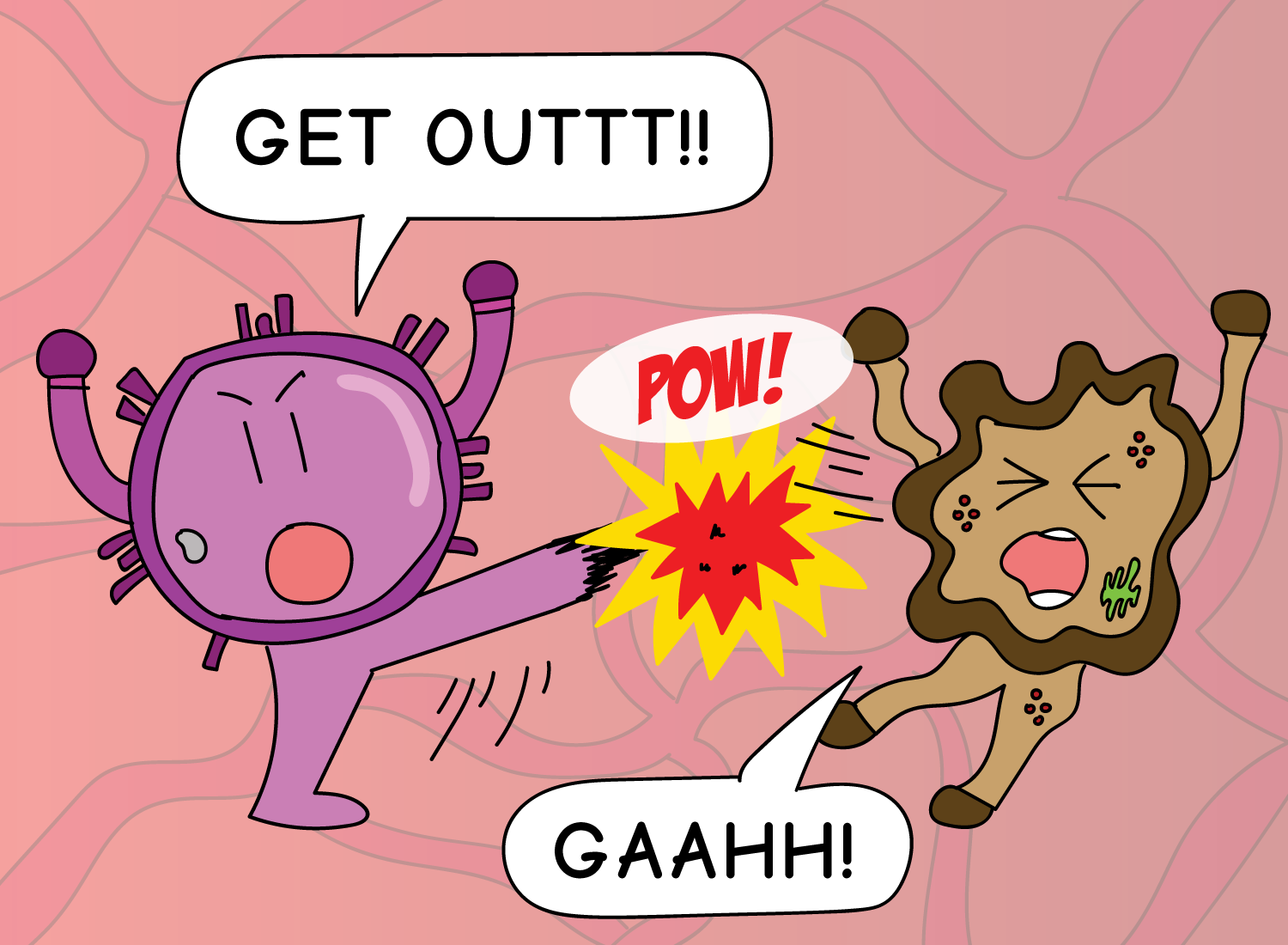

Everyday, the cells in your body are being replaced.

This process is seamless, and you’re usually not aware of it as it’s going on. If a single cell is replaced, then nothing seems to have changed, right? You’re still you, and life continues. In fact, billions of cells die and are replaced each day without us noticing a thing.

But things get interesting as time goes on.

Let’s say a year later, 20% of your “original” cells have been replaced in this manner. As time passes, this percentage creeps upward to 50%. Then 70%… 80%… and within a decade or so, almost all of your cells have been swapped out and revamped.

So this begs the question…

If each building block of your material existence has been replaced, are you still the same person you were a decade ago?

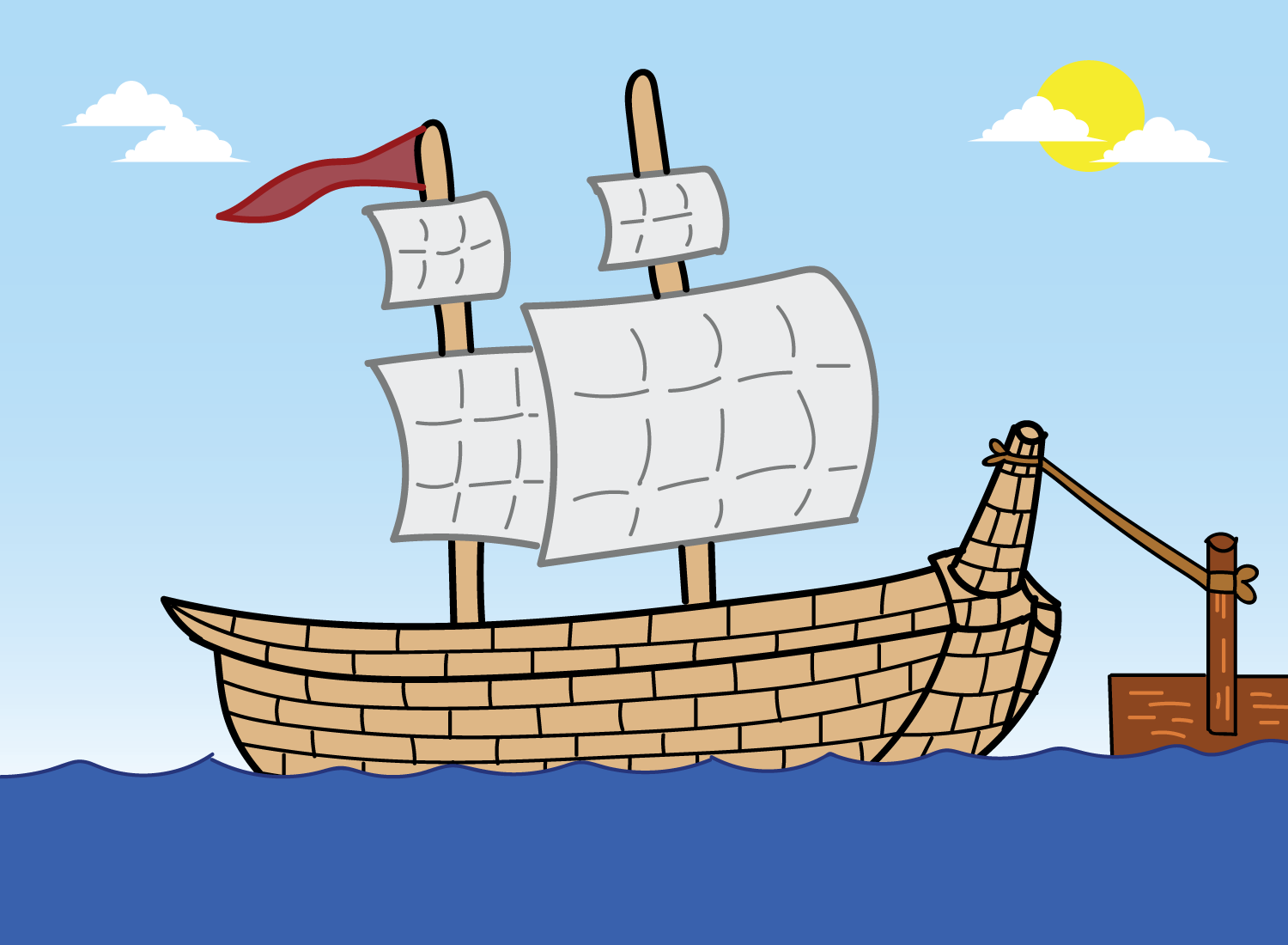

This is a version of the ancient thought experiment known as the Ship of Theseus. It follows the same narrative as the human cell replacement scenario, but using a ship that was once manned by an Athenian badass named Theseus.

Since Theseus was such an amazing dude, his old wooden ship was to be memorialized at a nearby harbor for all to honor him. The problem with wooden things, however, is that they tend to decay. So as the years went by, each wood plank needed to be replaced with a newer one.

This process continued as the years became decades:

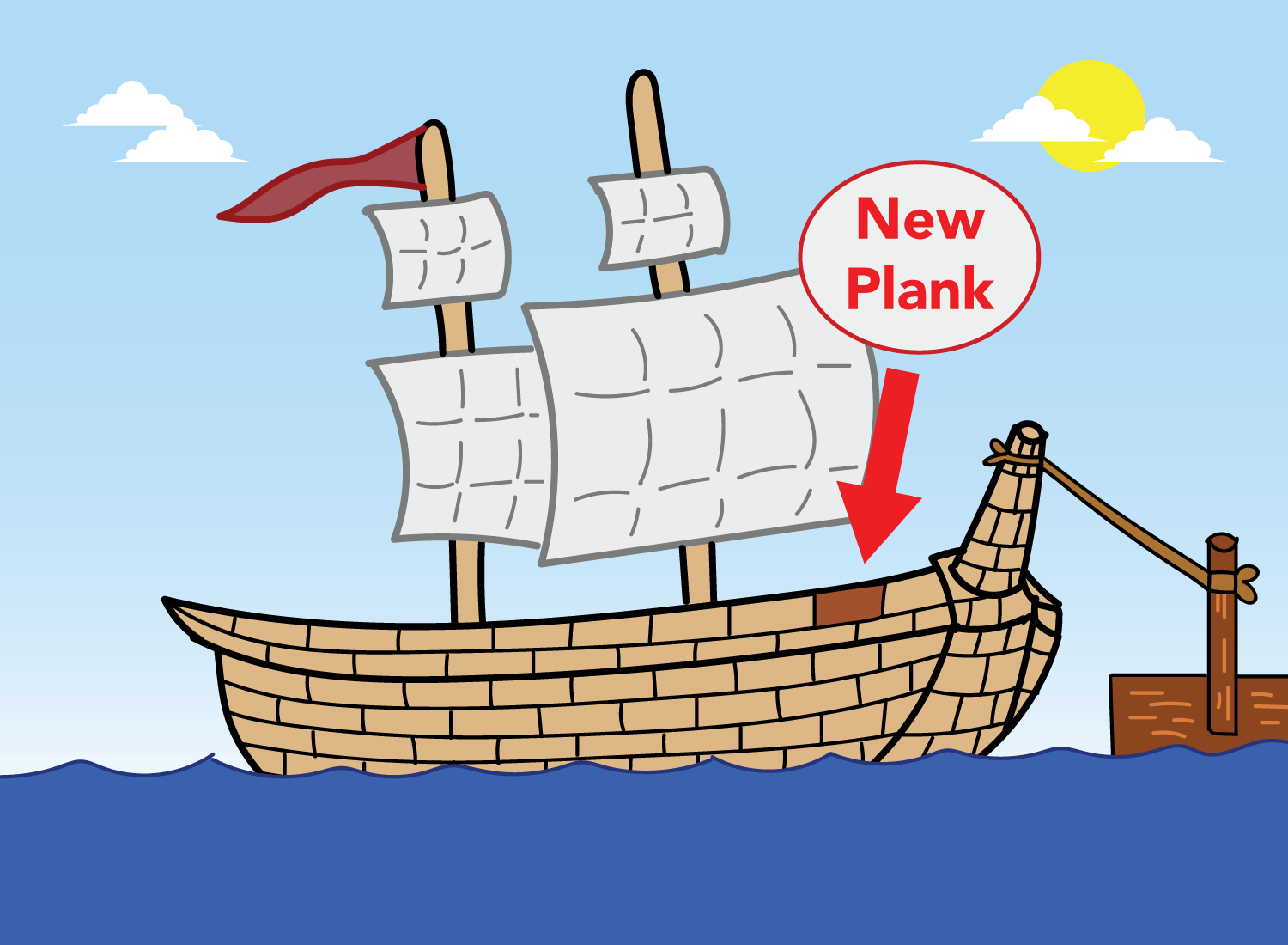

As decades became more decades:

Until a century later, the final plank from the original ship was replaced:

Is the resulting ship still Theseus’ ship?

Philosophers have offered various solutions to this paradox, and some are easier to follow than others. Some say yes, some say no, some say it’s somewhere in between, and some (annoyingly) say that the ships are just concepts so they don’t even exist in the first place.

As is the case with many thought experiments, I find that the question itself is far more interesting than the proposed solutions. The question of what gives you your identity is fundamental to how you view yourself, and dictates every action you take. But how do you define identity, given that every single thing about us is replaceable?

The paradox of Theseus’ ship forces us to ponder this crucial question.

The cell replacement scenario takes a strictly material approach, viewing our individual cells as the building blocks of who we are. While it is true that we are all reducible to clusters of atoms, there appears to be more to our identity than our bodily existence. This is because our particular arrangement of atoms have somehow led to the emergence of consciousness, which took things to a whole other level.

Consciousness has led to an endless array of interesting attributes: we can create vivid memories from experiences, we can express how we feel about things, and perhaps most importantly, we can reflect on ways to make shit better.

This latter ability to solve complex problems is at the crux of our evolutionary success, and is arguably the most human thing about us. Through this feature, we have developed the power of actionable intention: no longer do we have to rely on the forces of nature to blindly carry us to our destiny – we can now create the conditions ourselves and create our own paths.

One thing that is often overlooked when it comes to Theseus’s ship is this very element of intention. While most of the focus is on the gradual replacement of the planks, there’s a key question that often goes unaddressed: why do we even want to replace the planks in the first place?

It probably has to do with our ability to envision an idea of what we want in the future, and to act now to gradually get us there. When the Athenians knew that Theseus’ ship would be memorialized, they envisioned a future in which the ship would be in its original condition, acting as a beautiful reminder of when their beloved hero was alive. Knowing that the laws of nature would eventually turn the ship into a heap of dust, they had to create the intention to beat natural decay and replace the ship’s parts themselves. This type of intentioned action was the only way they could keep the idea of Theseus’ ship alive.

Intent plays a huge role in the shaping of identity, and this desirability of some future state also applies to the concept of the self. When we make the effort to live a better life, we put ourselves on a path that moves us away from our current selves and toward a more desirable state of being.

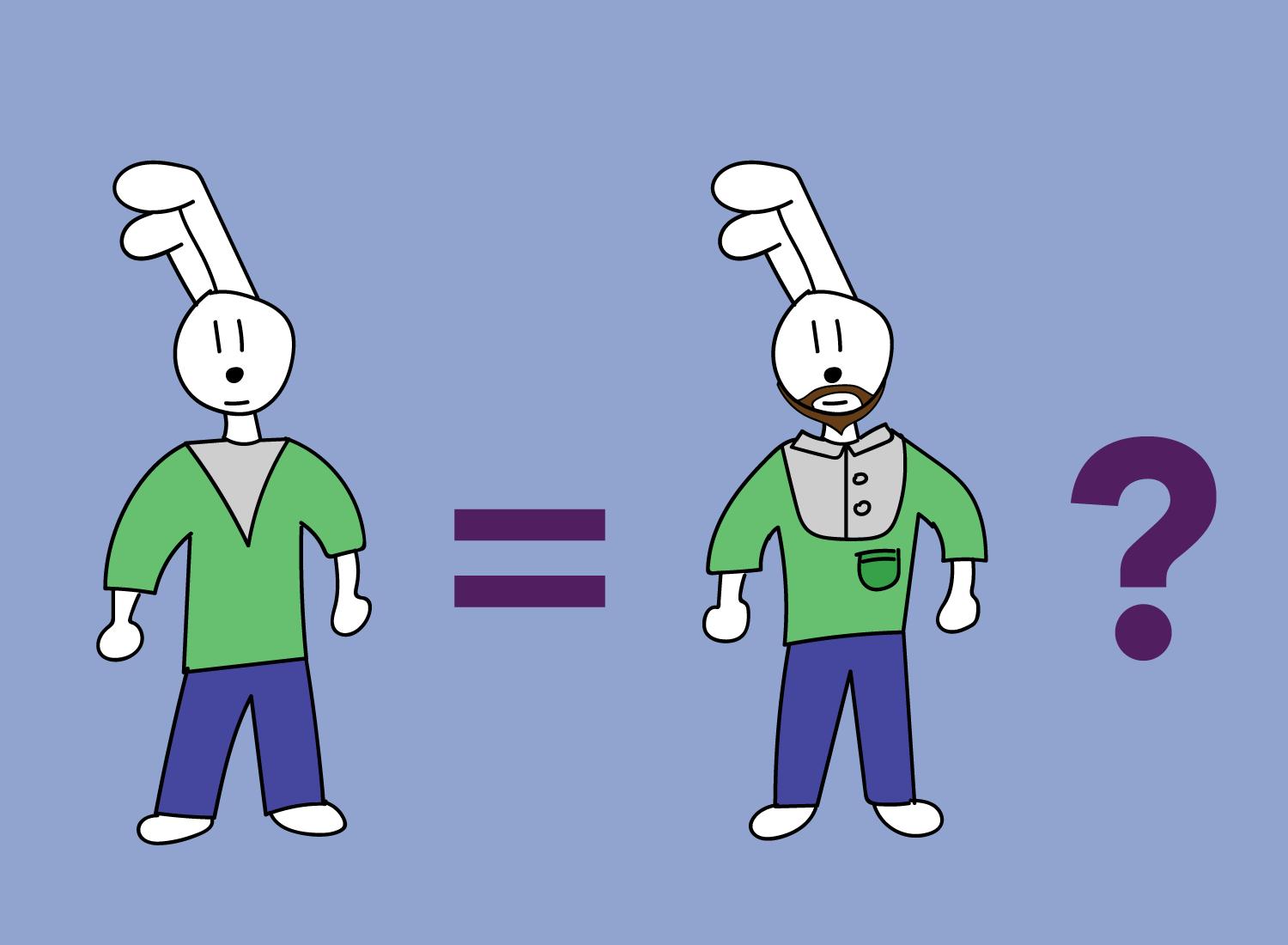

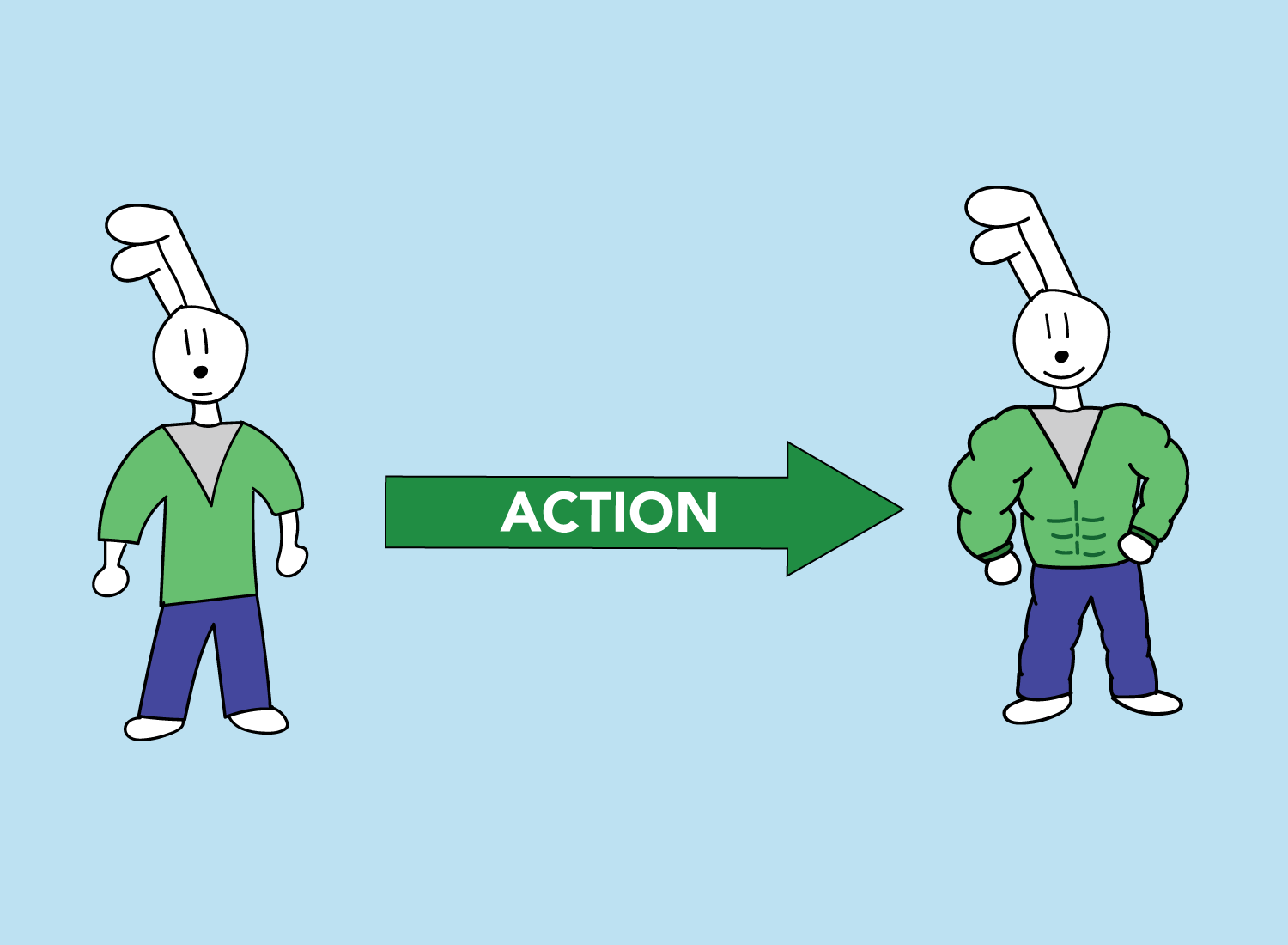

This is the core thesis of today’s self-help movement, which has cemented itself as the path toward the idea of a “better you.” On one side, there’s the “you” that’s sluggish and unproductive, and on the other, there’s the “you” that is fit and getting shit done. Self-help books, podcasts, and courses are designed to bridge the gap between these two ends of the spectrum, and if you add in actionable intention, you should find that you have transformed into a better version of yourself.

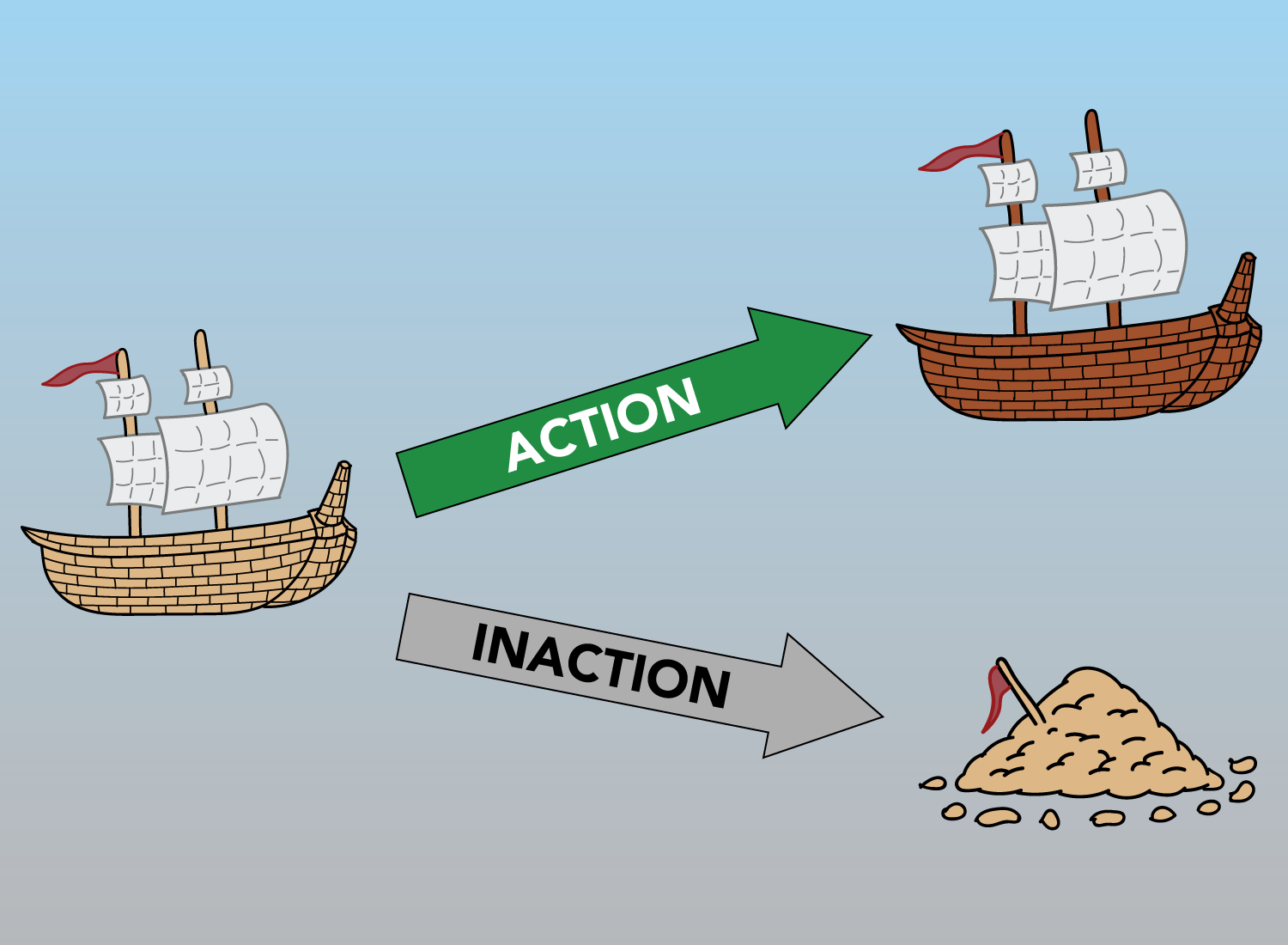

The paradox of Theseus’ ship overlaps quite nicely with the anatomy of self-help. In both situations, there is a current state that is being embodied:

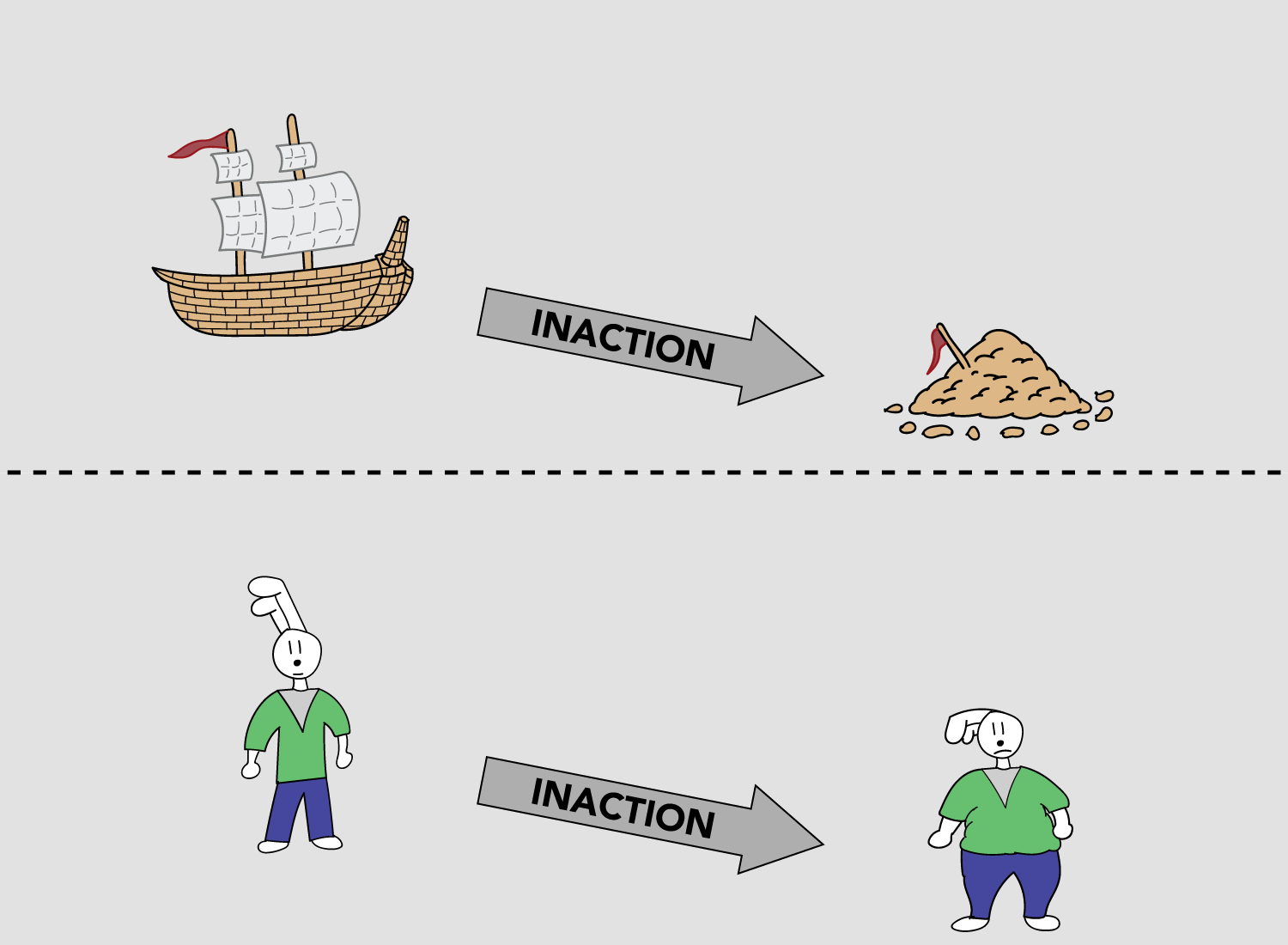

If there is no intention to stop the natural disorder of things (entropy), things won’t end well for either the ship or for our unproductive selves:

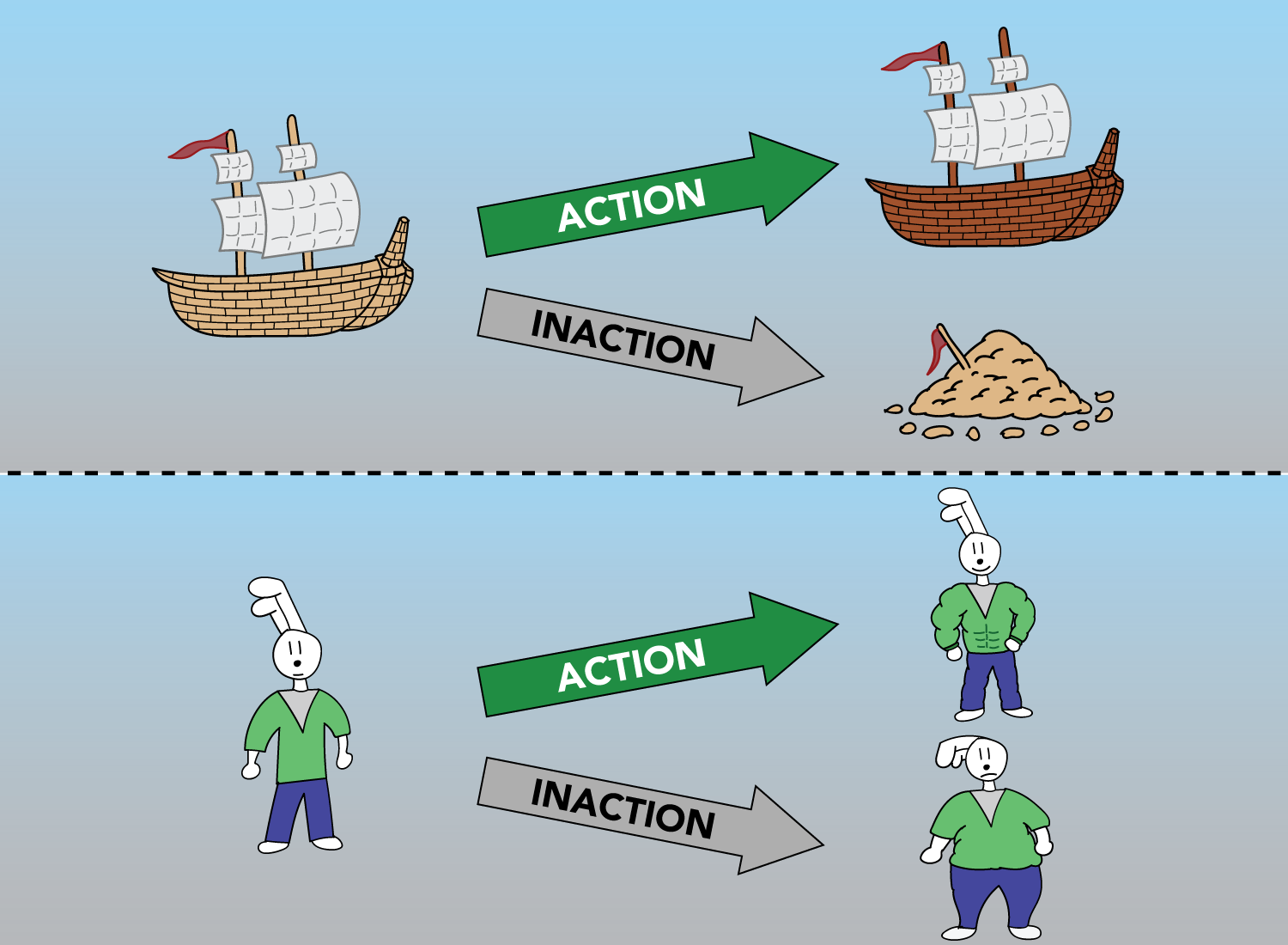

So to solve this, we must find the problematic areas and replace them with better parts / solutions to end up at the desired state.

At the end of this process, you now track all your work hours in the name of productivity, only eat the things that the health coach told you to eat, and do all the abs exercises detailed by your favorite workout guru. You feel like you’re in a great place, but the same question hovering above the Ship of Theseus remains:

After all these changes, are you still you?

To answer this, we have to first explore what shapes one’s identity, and what the hell it means to improve upon it.

Identity as a Sum of Your Capabilities

Clayton Christensen is an acclaimed author and business professor at Harvard University, who is perhaps most famous for his work on the innovator’s dilemma and the coining of the phrase “disruptive innovation.” In 2012, he published a book titled How Will You Measure Your Life?, which despite the self-helpy title, is filled with many great insights.

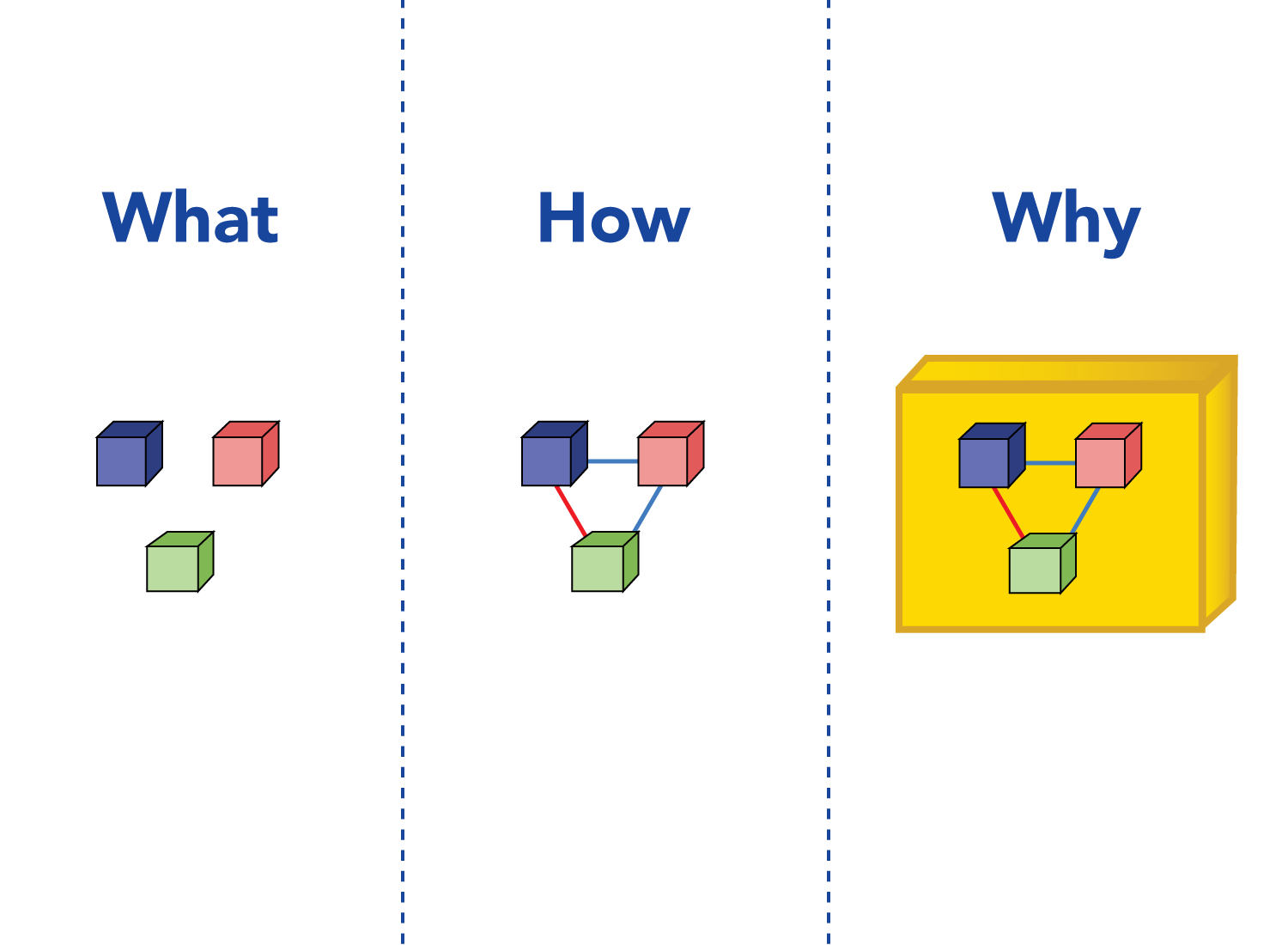

In it, he breaks down the anatomy of a corporation into its underlying “capabilities,” or the factors that determine what it can and cannot do. These capabilities make up the identity of the company, and fall into one of three areas: resources, processes, and values.1

Resources are the tangible things a company has that allows them to operate effectively. These include its employees, technology, customers, cash, credit lines, product designs, brands, information, etc. Some people think that having abundant resources is enough to drive success, but of course, they are forgetting that it’s just one of three critical categories.

Processes are the more intangible forces that govern how these resources will be used. They represent the “ways in which [the company’s] employees interact, coordinate, communicate, and make decisions.” Essentially, processes are what organize and move the resources so they can work together to drive growth.

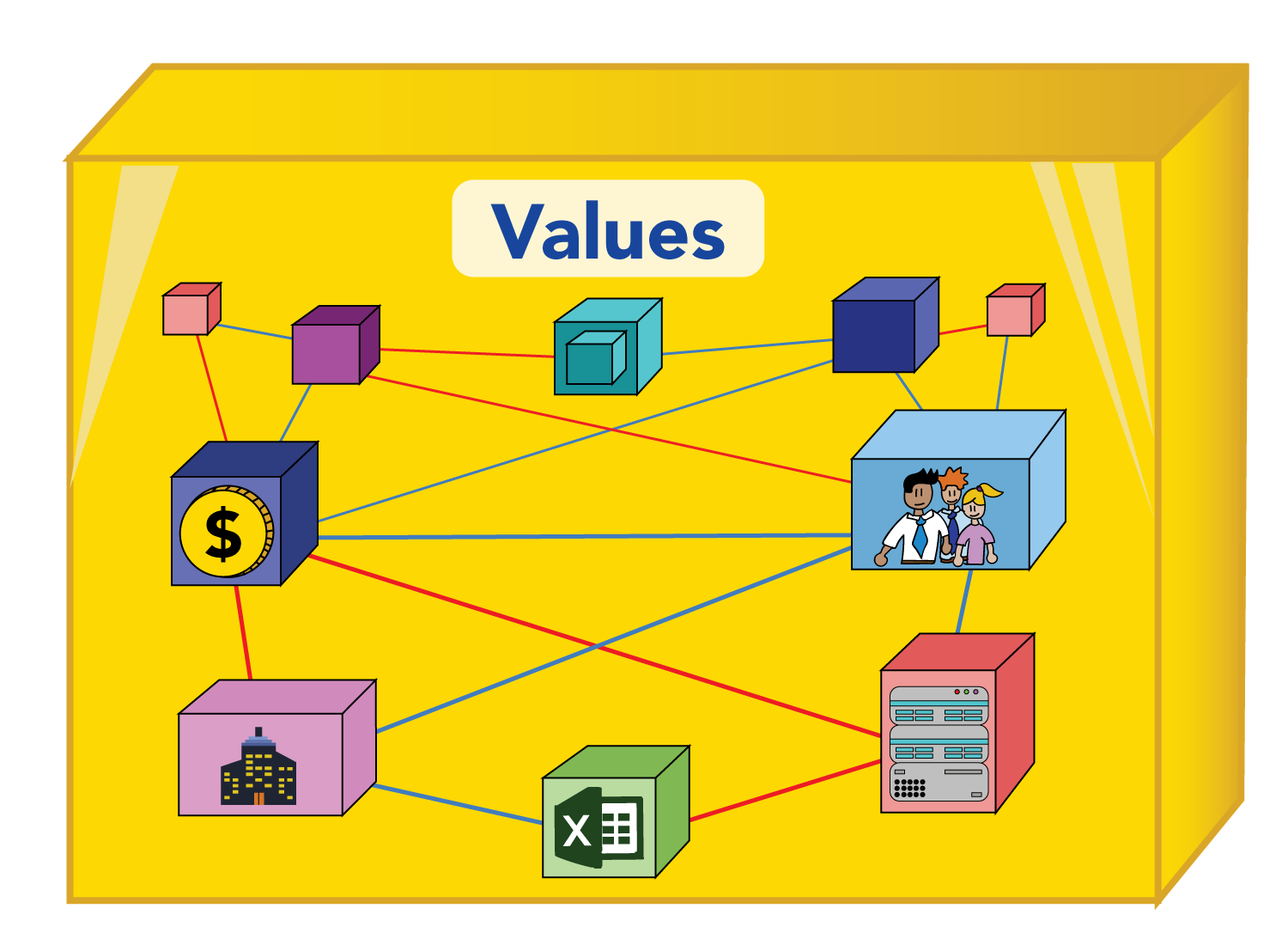

Finally, there are the company’s values. Christensen argues that this is the most important capability, as these are the foundational priorities that drive the direction of the company. They offer clear reasons for why the company does what it does, so each employee can make independent decisions that align with the organization’s culture.

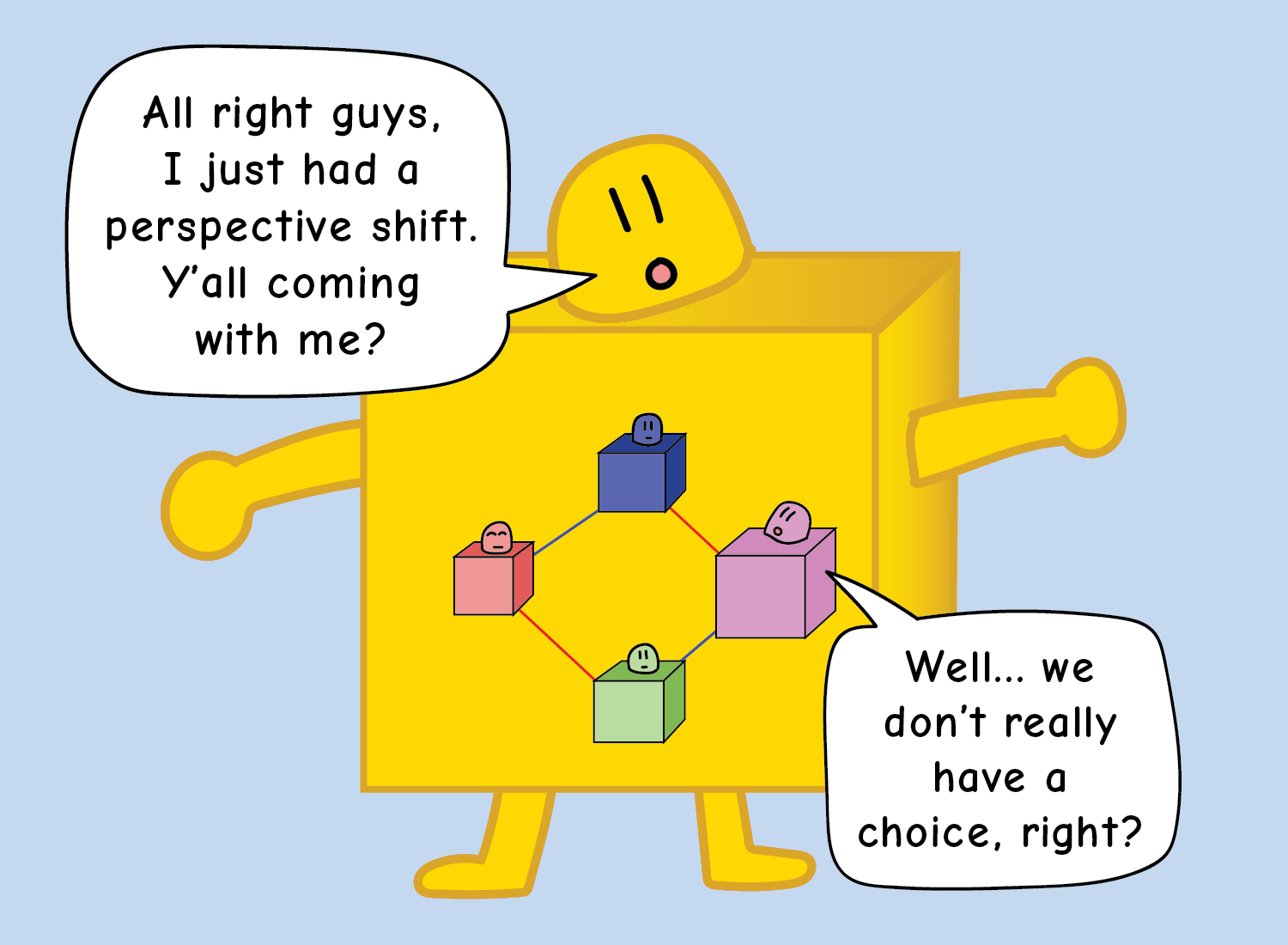

Values are the all-encompassing gold blocks that control everything; whenever they shift, both the resources and processes move accordingly.

As we will see a bit later, this Resources, Processes, Values theory of capabilities applies to individuals as well. But the main reason Christensen outlined this model was to warn the reader of the dangers of a common business practice: outsourcing.

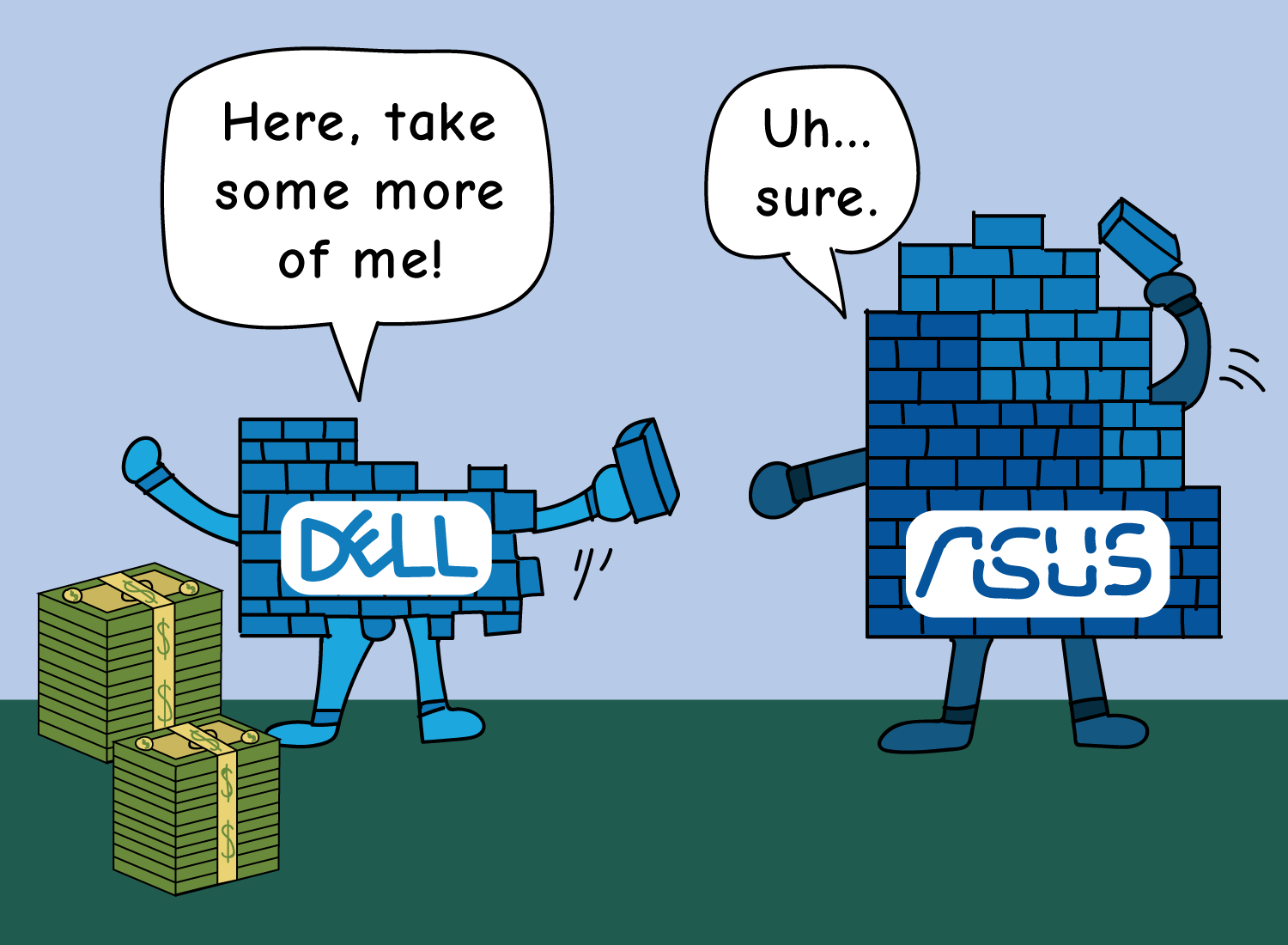

He offers the cautionary tale of Dell, a once-successful PC manufacturer that reigned supreme in the late 1990s. In an effort to reduce its operating costs and please investors, Dell began outsourcing their computers’ motherboards to a Taiwanese component supplier named Asus. This seemed to be a win-win scenario for both companies (Dell got to remove assets off their books while Asus made money), so both wanted to push things further.

It wasn’t long before Dell was outsourcing the assembly of the entire computer to Asus, along with the management of its supply chain and all the designs of the PCs themselves. Pretty soon, Asus built and shipped all of these computers; the only thing that indicated it was a Dell computer was because it said so on the machine.

Then, in 2005, the inevitable happened. Asus announced their own brand of computers, using all the knowledge they gladly inherited from their former partner. This dealt a serious blow to Dell’s PC business, which hasn’t recovered since. Dell’s move to outsource their components and activities may have produced favorable numbers in the short-term, but they ended up outsourcing away everything that made them unique and valuable.

Viewing Dell’s mistake through the lens of Christensen’s theory of capabilities is revealing. When it comes to outsourcing, Christensen states that you must “figure out what capabilities you will need to succeed in the future. These must stay in-house – otherwise, you are handing over the future of your business.”

For Dell, outsourcing some of their resources was a relatively safe thing to do. Having Asus build the motherboards helped Dell take some assets off their books and sell their computers at a lower cost, which created a win-win scenario for both companies. But when Dell started transitioning their supply chain processes over, they took a step into “handing over your future” territory. This would prove to be an early move toward giving Asus everything they needed to create their own brand of computers.

What truly fucked Dell, though, was when they gave away their values. Instead of keeping innovation as their core value, they replaced it with short-term profitability (aka “pleasing Wall Street”). This drove every subsequent decision they made, which ultimately led them to outsource their entire PC business out. The values that created their empire in the first place were shipped abroad, with companies like Asus repeating its benefits and creating more sophisticated products and components as a result.

When you strip away your values, both your resources and processes go along with it, and that is when your identity has fundamentally changed. This is when the “newer” Theseus’ ship is no longer the same ship. It may be recognizable from the outside, but the resulting identity is not grounded in any prior version of itself.

Let this serve as a cautionary tale of what self-help can do to the self.

The Capabilities of the Self

An individual’s identity can also be summarized by Christensen’s theory of capabilities as well. Each of us also have resources, processes, and values that dictate the way we view and act within the world.

Our resources are the things that determine what we can and cannot do. Some of these are tangible, including the wealth we have (whether earned or inherited), the schools we have access to, the material possessions we own (homes, computers, phones, books), the list goes on. Others are intangible, like the talents we possess, the knowledge we’ve obtained, and the relationships we’ve built.

Our processes dictate the way we use those resources. Similar to a business, they are mostly intangible, and consist primarily of how we think, how we solve problems, and how we collaborate with others. They allow us to take a good look at the resources available, and figure out how to arrive at an optimal solution.

The most important thing – our values – are the reasons we do the things we do. They determine how we make our decisions in life, and act as the guiding principles for our actions and perspectives. They are formed as we learn more about ourselves, and our resources and processes follow their directive.

To illustrate how they all work together, let’s take this splendid guy, who wants to write a blog post about why Pluto was demoted from our solar system.

His resources are his computer, his knowledge about space, the abundance of resources about the subject, and of course, his ability to write. The processes are the ways he consolidates his research, how he thinks about structuring his ideas, and how he schedules his time to write. His values are the reasons why he even wants to write this post to begin with. Maybe he’s the kind of person that is fascinated with underdog stories, or he simply enjoys being an educator, or he’s just curious about things he doesn’t know enough about.

Christensen says that “[r]esources are what he uses to do it, processes are how he does it, and priorities are why he does it.”

These three capabilities all work together, but there is a hierarchy here. Your resources are nothing without processes, and processes aren’t created without values. Values are developed somewhat slowly, as they are the result of subjective experience, biological tendencies, your upbringing, and the relationships you build with others. They are the most resilient and change-resistant, making them the building blocks of a continuous identity.

Processes are much more susceptible to change, as they are developed through experimentation, trial, and error (what doesn’t work is iterated upon). Resources, however, are always changing – the moment we earn another dollar or learn how to do something, our available stockpile has shifted.

The nature of self-help requires it to focus on these ever-changing parts of our identities. A self-help author, podcaster, or speaker cannot possibly understand the personal values of each member of his audience, so he must target the more dynamic parts of the self: the processes and resources. It’s much easier to tell someone how to get the things they want, then why they should want them.

But sometimes they try to sneak in the why, and that’s when it gets tricky.

The Smuggling In of Values

When you pick up a self-help book, you’ll find that most of the pages are filled with process improvements. It will outline how you can wake up earlier in the morning to get stuff done, how you can set up your environment to eliminate distractions, and how to form long-lasting habits. The assumption is that if these processes are followed, then the resources should flow in accordingly.

While this sounds great, there is an overarching assumption at play: the author assumes that the reader’s values are congruent with his own. A book on habit formation sounds great if the reader wants to get fit, but is terrifying if the reader is using it to inspire his development of a biological weapon. It’s convenient for the author to assume that most practical use cases of his book will be the former, and not the latter.

It’s a solid assumption to make, given that terrorists probably aren’t browsing through the self-help sections of your local bookstore. However, it illustrates an important point: while self-help appears to improve one’s processes, it can also smuggle in the author’s own values as well. The how to get what you want is intertwined with the author’s why you should want it, and this is problematic. As we saw with the Dell/Asus story, outsourcing some of your resources and processes can be beneficial, but transitioning out your values can be destabilizing.

To see this value-smuggling in action, let’s briefly revisit our humble writer and his blog post on Pluto’s demotion.

Mr. Pluto slogged his way through a bunch of research articles and Neil deGrasse Tyson videos, but was stuck on the actual writing process itself. He was having a difficult time structuring all his research and putting a word down to start his post, so he figured he could use some help. He went to his local bookstore and picked up How to Be a Dope Writer by Wright McRight, which details some strategies writers can use to level-up their craft.

There were some helpful processes outlined in the first chapter, like sitting down everyday to write at a specific time, or aiming to write just a hundred words each session. These writing tips gave him the fuel he needed to get started, so he decided that the rest of the book was worth reading.

But about halfway in, he came across a chapter that looked something like this:

That title sure sounds helpful, and it probably has a lot of good recommendations to do just that. But smuggled deep into its pages is the author’s personal value:

You are a writer because you want to reach a ton of people.

While this value may be true for many writers, it may not be for our Pluto blogger. Perhaps his values were more about writing something he was simply interested in, or challenging himself to do something he was initially uncomfortable with. Hell, he would’ve been happy if only his family read his post, or just that he wrote the damn thing to begin with!

But if our Pluto blogger read the chapter and found it compelling, that may lead him to shift his values about why he writes. What was previously just a curiosity-driven project now has the expectation of pageviews attached to it, which means his reasons for writing have changed. And when this happens, the lens in which he views this project (how we writes the post, how he presents it, how much he identifies with it) shifts as well.

Many self-help resources operate under the guise of improving one’s processes, but smuggle in the author/guru/coach’s values along with them. Without knowing who the author is personally, it’s difficult to know if their intentions are sound, and if they should becomes ours as well. Our values are the most important thing we have, and they should be shaped by years of personal experience, not by a few pages or speeches from a distant public figure.

The reasons you do the things you do can’t come from someone else; they have to come from within. While books and advice can give you some good ideas, they don’t mean shit unless you go out and experience life first-hand. It doesn’t matter what you know if you don’t want to explore why you should even know it.

This is why telling a smoker to quit the habit doesn’t work. Everyone, including the smoker, knows it’s terrible for his health, but that knowledge is useless. The only way to quit is if the smoker – and only the smoker – places his health as his dominant value, ahead of any pleasure he gets from the habit. The path toward any type of action starts with a self-driven reason, and that can only come through introspection and independent reasoning.

The danger of value-smuggling lies in its hijacking of personal experience, and the replacement of it with another’s directives. Sometimes it’s overt, sometimes it’s subtle, but it certainly compounds over time. It may seem like you’re simply swapping out bad processes for new ones, but if your values are outsourced with each replacement, then your ability to think independently leaves with it.

This is what happened to Dell, and it can certainly happen to us.

To be clear, the takeaway here is not “fuck self-help.” There are actually a lot of good self-help resources out there, some of which have helped me develop productive patterns of thinking and daily routines to support them. Instead, it’s about pausing whenever you approach the genre and asking:

Can I use self-help without losing myself in the process?

The Ship of Theseus provides a helpful framing for this question.

The individual planks of the ship, or our resources, will always shift. That’s what happens as we learn more about ourselves.

The ways we put these planks together, or our processes, determine how we get the most out of each individual plank. That’s what happens when we act upon what we have learned.

Self-help shines when it comes to updating our resources and processes. Learning how to upgrade your ship is great, especially if you have the access to learn from the best (which nowadays is just an internet connection). You’re still you; it’s just your tools that have changed.

But avoid self-help when it tells you why you should do what you do. If the Athenians found out that Theseus’s ship will eventually be gifted to some distant king no one cares about, they’ll say “fuck off” and let it rot. The reason doesn’t resonate, so that’s the end of the story. No more plank replacements to consider; no more paradox of Theseus’s ship to ponder.

That’s the power of personal values, and they govern everything we do.

If you outsource your values to others – whether it’s self-help figures, your peers, or even your parents – you cease to be you. You slowly become them, and the worst part is, you’ll wake up one day without knowing how it happened. That’s how value-smuggling works; it’s disguised as self-improvement, but results in self-replacement.

The key is to understand when self-help is genuinely trying to be useful, and when it’s trying to smuggle in someone else’s deep-seeded values. When viewing it through the three capabilities of the self, here’s a simple framework that I find helpful:

When someone tells you what to think, be open-minded. When someone tells you how to think, be cautious. When someone tells you why to think, be resistant.

You – and only you – can figure out that last part.

_______________

_______________

Check out these other More To That posts that explore the weird and elusive concept of the “self”:

Or if you’d rather just laugh about the absurdity of it all:

_______________

Sources

Clayton Christensen, James Allworth, Karen Dillon – How Will You Measure Your Life?

Charles Chu – Where is the ‘self’ in ‘self-improvement’?

Kathryn Schulz – The Self in Self-Help

Wireless Philosophy Video – Metaphysics: Ship of Theseus