God Is a Spectrum of Being

The most perplexing thing about the universe is how gorgeous it is.

Every time I go camping and look at the nighttime sky, I have a moment of awe for the harmonious nature of the sight above. Each star seems to have been carefully positioned by a masterful artist, with every inch of space having a purpose in this brilliant mosaic of light.

How can something so chaotic as a nighttime sky be so orderly?

How can something so complicated as the world be so elegant?

How can the universe be held together by physical laws instead of devolving into disarray?

These are the questions that point to the existence of something greater than ourselves. Because whenever we find harmony in what should be utter chaos, we believe that some higher force has organized reality so that it could be more comprehensible to us.

When we ask someone if they believe in God, we’re asking them if they believe in this mysterious force of order. Or to put it more accurately, if they think this order is attributable to a spiritual being that can be readily referenced.

The problem with this question, however, is that we expect the answer to be one of two things:

To say that you’re an atheist is to deny God entirely. So if you were asked to explain the nature of our world, you would likely point to the laws of physics or to relegate it to “the fundamental mystery of the universe” (and how you don’t need God to appreciate the beauty of it).

While that’s a great rational response, it fails to address something important: Why the hell is the universe so harmonious and orderly in the first place? How is it possible that gravity, planetary orbits, and all sorts of natural phenomena can be condensed into compact equations?

Physicist Michio Kaku expanded on this thought in a recent interview:

On a single sheet of paper, we can write down all the known laws of the universe. It’s amazing – on one sheet of paper! Einstein’s equation is one inch long. String theory is a lot longer, and so is the standard model. But you could put all these equations on one sheet of paper.

It didn’t have to be that way.

Even if we use the laws of physics to explain the universe, we cannot use them to explain why the universe is organizable into laws in the first place. Physics can describe the nature of what is, but it can’t solve the mystery of why nature is orderly as opposed to random.

As Kaku said, it didn’t have to be this way. Yet for some reason, it is.

Let’s now look to the other option, which is to declare your belief in God.

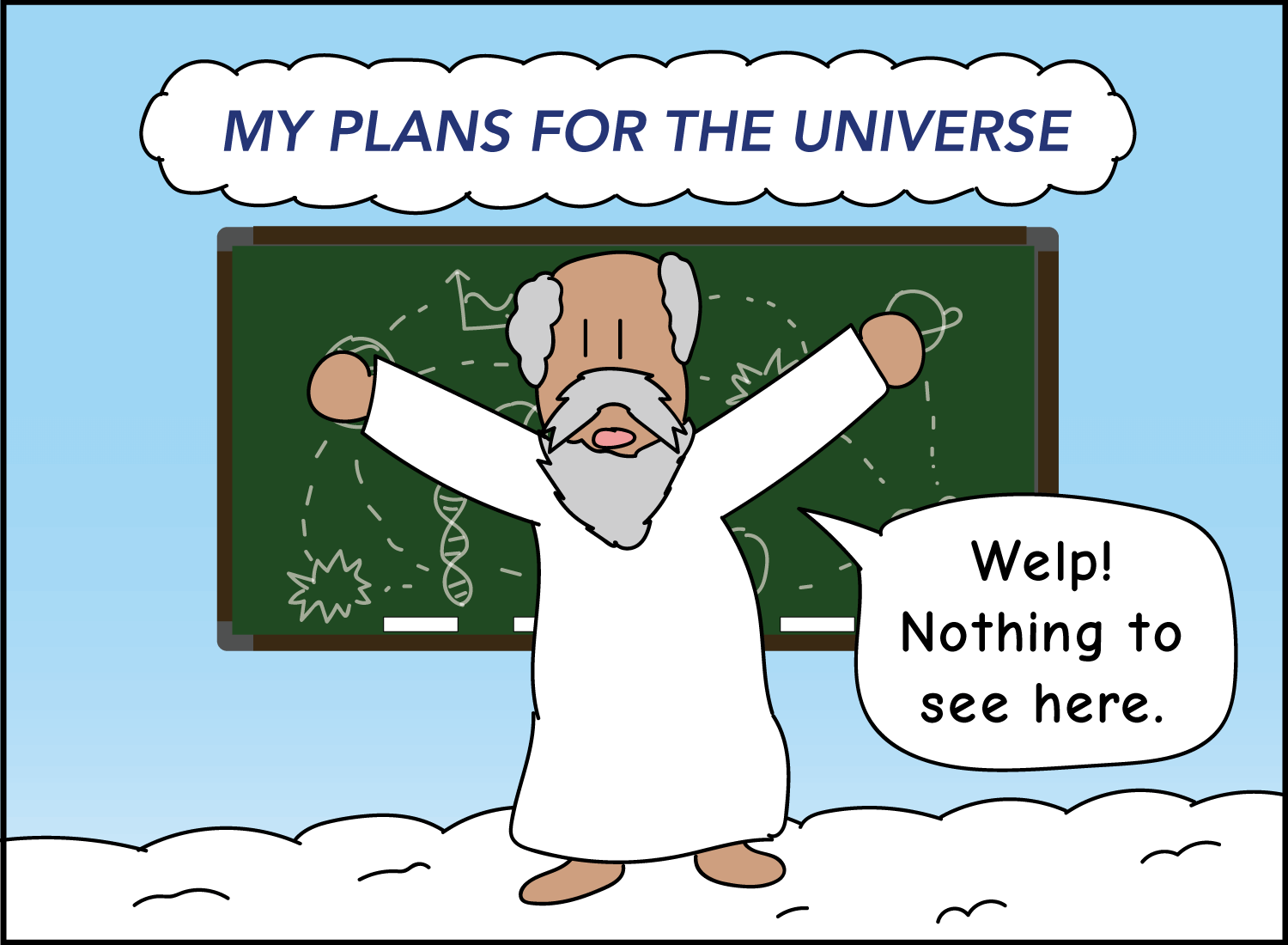

If you accept that God created this universe as an intelligent designer, then that solves the issue of order. But of course, it rarely stops there. For most believers, God’s involvement extends beyond the natural realm and into the ethical one. God isn’t just the architect of the universe, but also the moral arbiter that passes judgment on the people that he governs.

This is where the anthropomorphic God with human attributes emerges. The Abrahamic God is portrayed as an old bearded man in the sky, while Brahma of Hinduism is a red complexioned man with many heads and hands. These spiritual beings take on the form of something recognizable, yet occupy a higher realm that we must accept as incomprehensible.

In other words, God is both familiar and foreign. Familiar enough for us to love him, yet foreign enough that we must give up any attempt to understand him. When we say that “God works in mysterious ways,” it’s another way of saying, “who we are we to question God’s will?” Since we can’t understand the mysteries of the universe, we must outsource that knowledge to the plans of the Almighty One.

So on one hand, there’s a God1 that has built the universe and legislates its constituents as The Great Micro-Manager. On the other, there’s no God at all and the universe is governed by physical laws that are inexplicably orderly, to which we shrug our shoulders and say “that’s just the way it is.”

I don’t know about you, but to me, those options sound super unsatisfactory.

I’ve always found it strange that our answer to “Do you believe in God?” is expected to fall into one of these two bins. Perhaps it’s because the question itself is designed to have an either/or answer, but it’s also because our conception of God is problematic from the beginning.

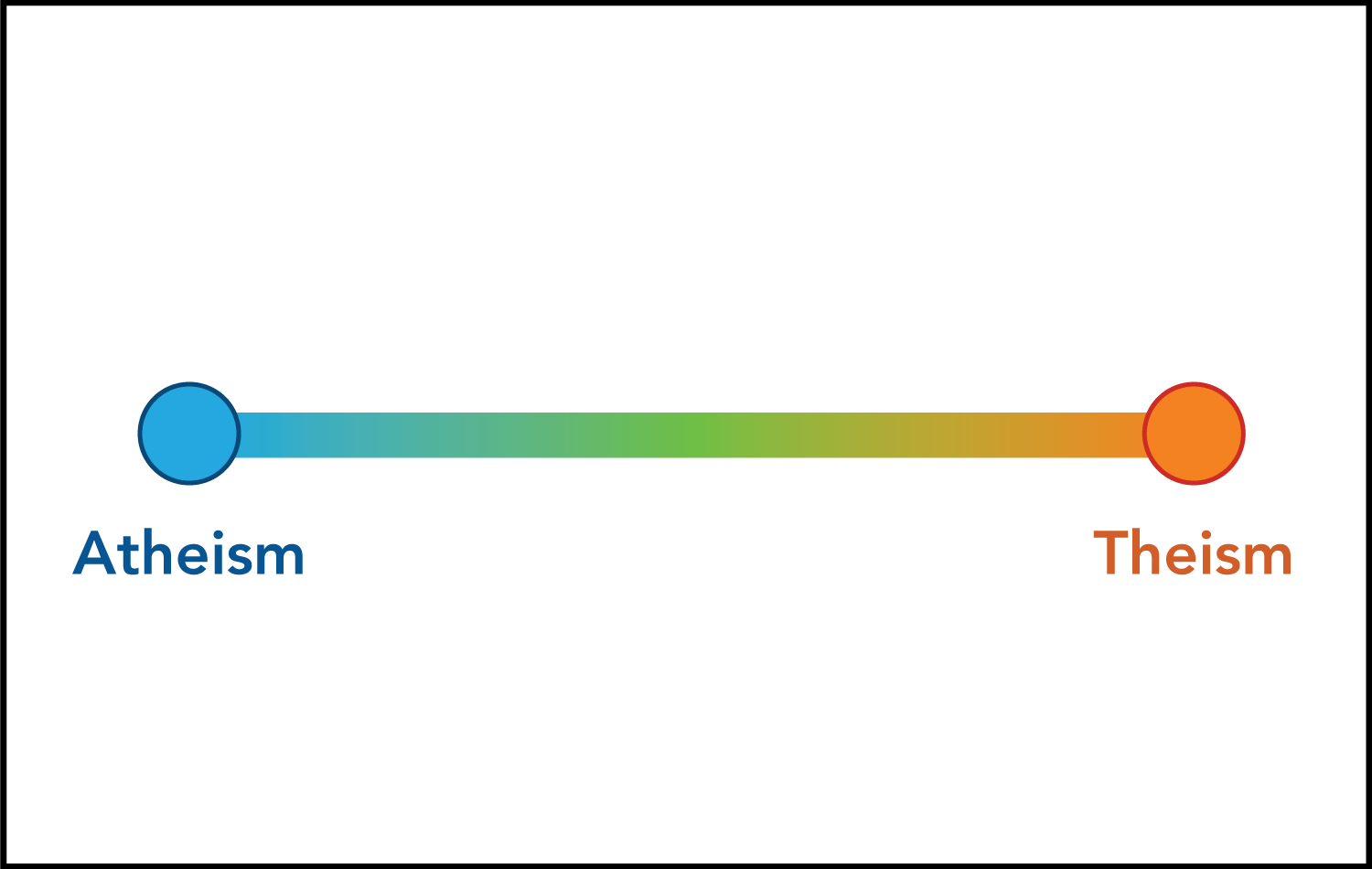

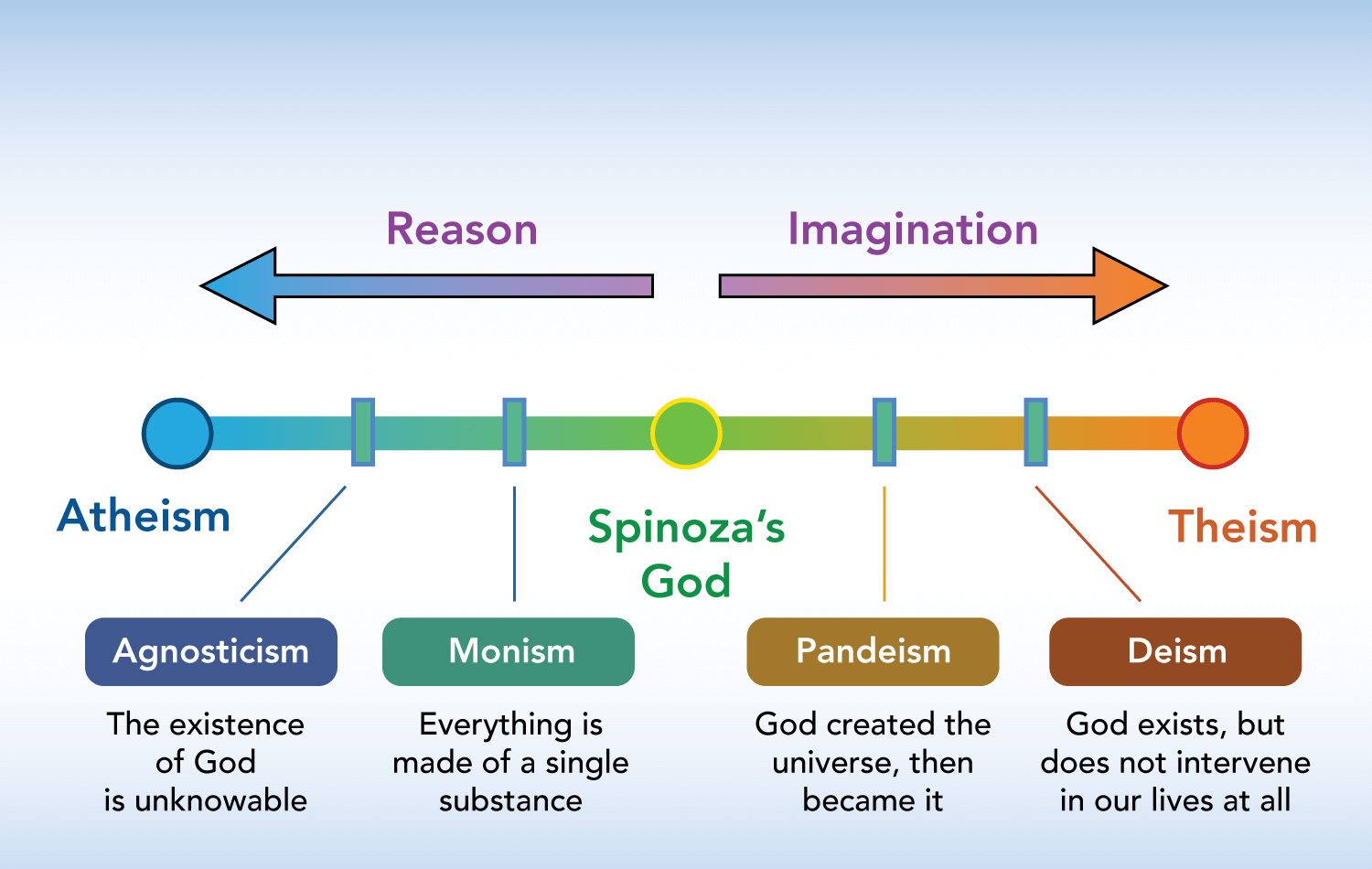

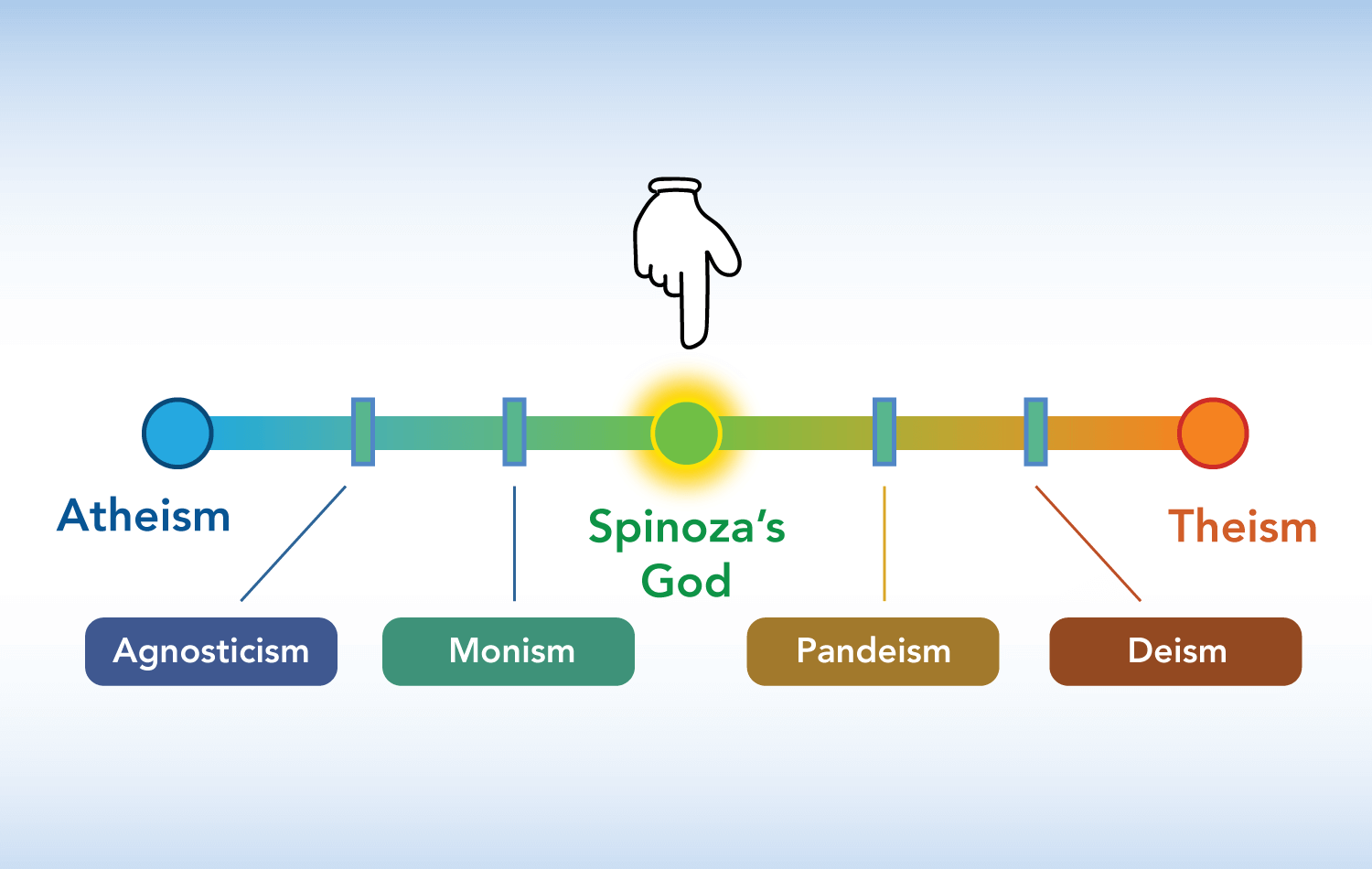

I think that the question of your belief in God is not a binary matter…

… but rather a spectrum that connects those two choices as endpoints.

This is what I call The God Spectrum, and it reflects the various conceptions of God that span from zero-belief to total-belief. One thing I’ve noticed is that belief rarely falls neatly into a “Yes” or “No” assertion, but rather a “Well, it depends…” clarification. And when it comes to something like God, that clarification can only be communicated through a nuanced discussion that is shades of gray rather than black-or-white.

The thing about this spectrum, however, is that there are far too many views for me to detail in this post. Just take a quick scroll through these Wikipedia pages on atheism and theism, and you’ll get an idea of what I’m talking about.

Rather than map out every possible view on this spectrum, I’m instead going to focus on just one key idea that acts as the midpoint. The midpoint is the most important thing to identify because it anchors all the other views in relation to it, which makes The God Spectrum much more useful as a tool.

So which view of God resides squarely in the middle of atheism and theism? Which one is able to synthesize both of these endpoints into something that’s both logical and mysterious?

I’ve looked through many of the choices out there, and I think I’ve arrived at an answer. To pinpoint it, we’ll have to explore the thoughts of one of the great philosophers of the Renaissance era:

Baruch Spinoza.

The Midpoint of Spinoza’s God

To start things off, let’s first take a look at this ball of wax:

Since a lump of wax isn’t too exciting, let’s now shape it into a long rectangle and put a wick through it. Now we have a pretty cool thing, which we can use to do stuff in the dark:

Even though the shape of this candle is quite different from the ball, we would still consider both forms to be wax. And once the candle melts down to the shape of whatever plate was holding it, the resulting sludge is still wax too.

Essentially, the wax could take any shape, form, or color, and we would still recognize it as wax. There is something fundamental and unchanging about it that persists through any modification in its appearance. There’s something about its essence that doesn’t depend on how it looks, or how it relates to other things in the world.

Simply put, wax is going to be wax… no matter what.

To Spinoza, this fundamental nature of something is what he calls “substance.” There is some sort of substance to the wax that makes it identifiable as wax, regardless of what form it takes. In other words, substance doesn’t depend on its appearance to define what it is.

This notion of “substance” is a super old philosophical concept, and it could get confusing really quickly. To make it concrete, let’s give an example of what it is not so you get the full picture.

Here’s one of my favorite inanimate objects in the world: a book.

If an alien came down and asked me what this object was, I can’t just say that “it’s a book.” That would make no sense at all. In order to explain what a book is, I would have to explain so many material and conceptual elements to the alien to slowly build his understanding of it. On the material level, I would have to tell him what a page is, and how a page is made out of a tree. But of course, if he had no idea what a tree was, I’d have to break that down for him too.

And on the conceptual level, I’d have to explain language, and how we were able to record it using the invention of writing. But to explain writing, I’d have to discuss how reading words was an effective form of communication for the human species, and all the implications it had on our understanding of the world.

And by the time I’ve finished explaining things, I’ll be 100 years old, and the alien will have long departed to spend his time on more fruitful endeavors.

A book cannot be substance because it isn’t self-explanatory. In fact, even wax isn’t either because its essence can be further explained by its chemical composition. The same goes for something as infinitely adaptable as water too.

Spinoza realized that every individual thing in the universe (including us) can only be explained in relation to something else. So if that were the case, how could there be substance at all? What was the independent, self-explanatory substance that everything was made of?

Spinoza thought about this for a while, and eventually arrived at a rather profound conclusion. He realized that the only truly self-explanatory thing is the totality of existence: the sum total of every individual object and relationship that exists (and has ever existed). Substance is that great mass of existence that extends beyond ourselves, our solar system, and even the universe. It encompasses the entirety of everything, and this giant mass of totality cannot be explained in relationship to anything else because it literally is everything.

And it is this wholeness of being that Spinoza calls God.

Since God is infinite, Spinoza argues that everything within this totality is a part of it. Every object – whether animate or not – represents a small fraction of God, imbued with the very substance that gives God its fundamental essence. A rock is a facet of God just as much as your neighbor is, along with whatever plant she’s watering in her backyard.

More importantly, Spinoza also referred to this totality of being as “nature.” Not nature in the modern sense of forests and mountains, but nature as the fluid state of harmony and order that runs through everything.

Nature is what is referenced when Michio Kaku said that the universe “didn’t have to be this way.” While we can observe the astounding patterns that govern the world, no one can explain why these patterns had to exist in the first place. Gravity is everywhere, but we will never be able to explain why it’s a thing to begin with. All we know is that gravity operates according to the laws of nature, making it just another facet of God.

By equating God with nature, Spinoza realized something that was super controversial for his time. In fact, it was so controversial that Spinoza asked his friends to publish his work posthumously so he could avoid a painful death that the Church would have dealt upon him.

His realization was this:

If God is nature, then by definition, God couldn’t be anything supernatural.

Religious stories are full of miracles and magical occurrences that attest to the existence of an external God. But to Spinoza, a miracle is just a natural event that we have yet to understand. Magic is something that hasn’t been observed with enough scientific rigor for us to unearth the law that governs it.

If God is nature, he couldn’t be something that exists outside it. He’s not some transcendent being in the sky doing miraculous things.

There is no grand legislator that passes judgment on us and intervenes in our affairs.

There is no anthropomorphic, divine being that cares about our suffering and listens to our prayers.

Rather, Spinoza says that God is “immanent,” meaning that he is in us and around us all the time. By recognizing this, we won’t look to some external moral code to develop our ethical systems. Instead, by understanding that we are all a part of God, we will treat each other as such, and that will inherently create a more virtuous society as a result.

When woo-woo people refer to the universe embodying some sort of cosmic “energy,” what they are really referring to is Spinoza’s God. On the other hand, when rationalists believe that there must be some force responsible for the harmony of the world, they are also referring to Spinoza’s God.

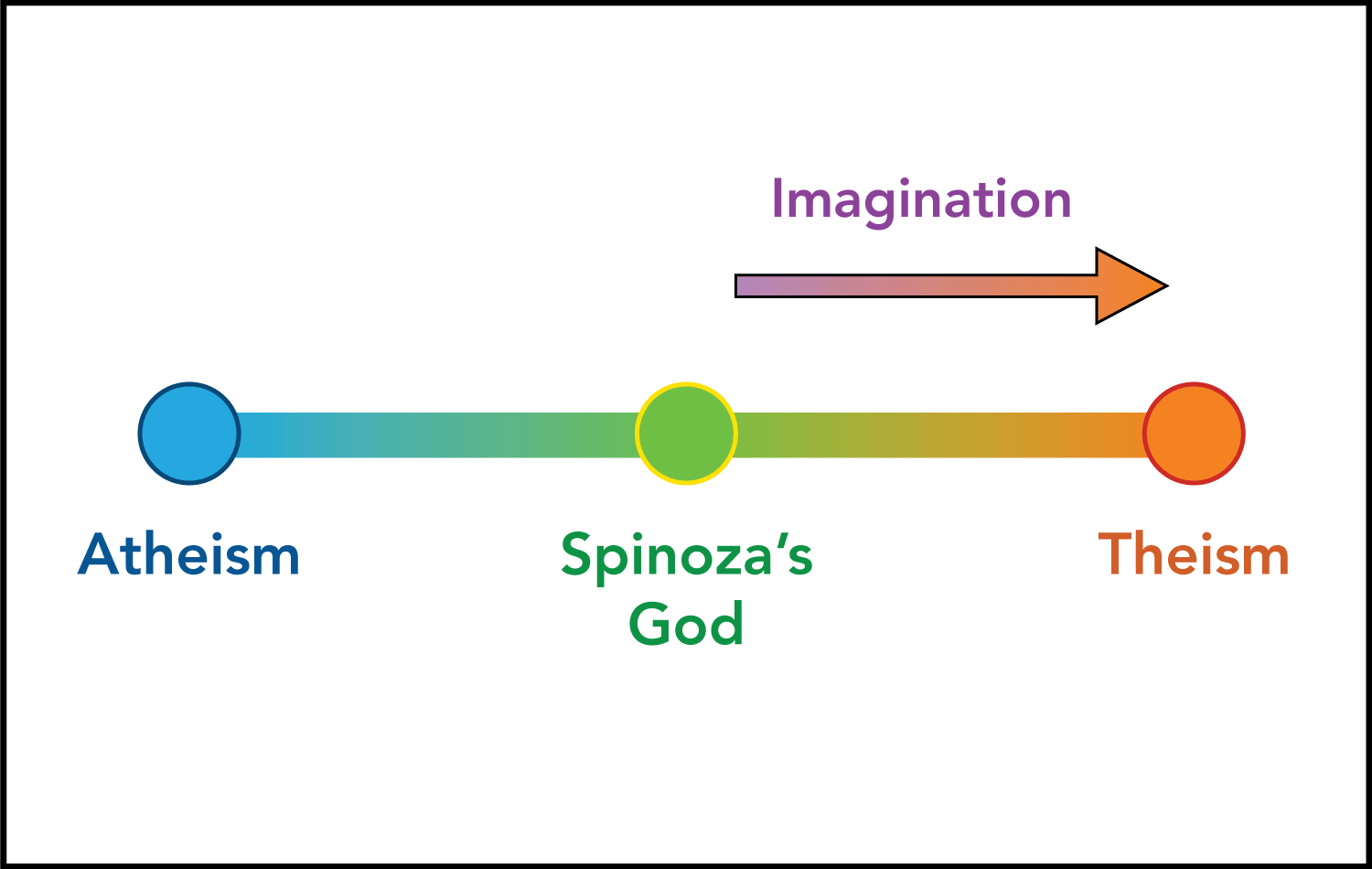

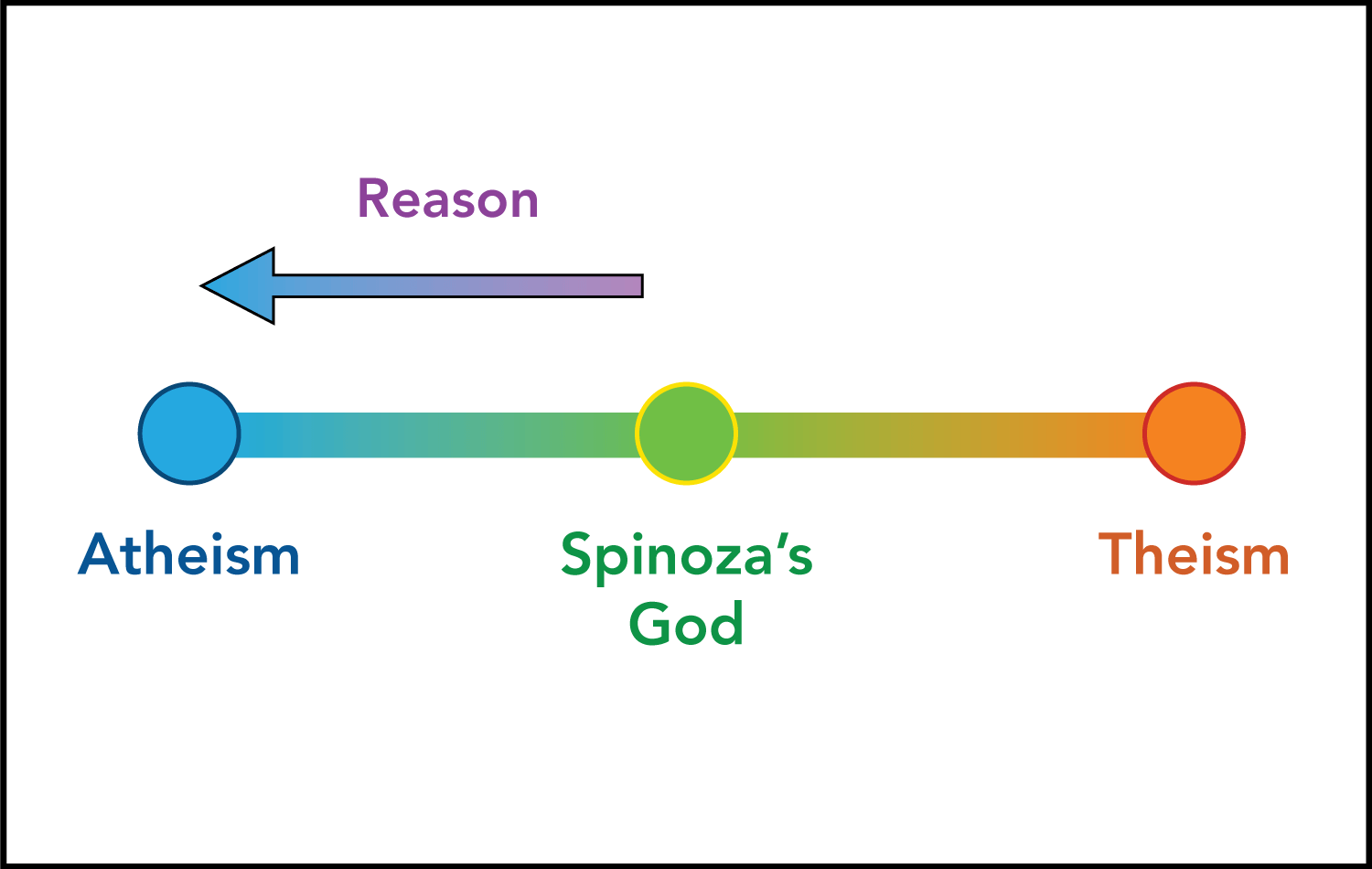

This is what makes Spinoza’s God the best midpoint for our spectrum. It synthesizes two types of knowledge that usually oppose one another, which Spinoza refers to as (1) reason, and (2) imagination.

Reason is the form of knowledge that gets us closest to the truth. And to Spinoza, the truth isn’t subjective. Truth is universal, and the only way to uncover it is through the usage of philosophy and science to unearth the reality of what connects us all (he refers to these as “common notions”). Your typical rationalist would find comfort here.

Imagination is the form of knowledge derived from our perceptions. It isn’t designed to be true or false, nor is that the goal. The purpose of the imagination is to organize our experiences into a system that we can collectively understand. It identifies our deepest feelings and memories, then weaves a narrative to help us make sense of them.

Spinoza argues that the greatest product of imagination is religion. We often get caught up debating whether religion is true or not, but Spinoza would say that we’re missing the point. Religion’s main purpose is to act as an organizational structure for us to behave and treat each other well. It has less to do with truth and more to do with function. He understands that humans are driven more by impulse and emotion than by rationality and reason, so religion must exist to anchor our moral compasses.

This tendency to use our imagination to organize reality is what takes us to the right side of the spectrum, where God takes on the form of something recognizable. The bearded man in the sky, the ten avatars of Vishnu, and so on. The more we try to organize experience into archetypal structures, we enter the territory of theism, and all the age-old stories that live there.

On the flip side, the more we use reason to understand reality, we start denying the notion of God altogether. Rationality presumes that the laws of physics are what govern the universe, and not an inexplicable cosmic force. Anything we designate as mysterious is simply a phenomenon that has yet to be understood.

The closer you get to the left side of the spectrum, the rational mind reigns supreme, and any notion of God fades away from the picture.

Spinoza’s God sits right at the intersection of these two forces.

It is God without any of the supernatural attributes. It is nature that encompasses all of existence without passing any moral judgments. And most importantly, its conception was the result of a rigorous philosophical examination, and not the product of a dogmatic belief system.

Spinoza’s God helps to explain why the universe is so gorgeous when it could have been so ugly. Why order exists when there didn’t need to be. If science uncovers what reality is, Spinoza’s God points to why it happens to be that way.

When Einstein was asked if he believed in God, he wrote:

I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.

For a man that contributed so much to scientific progress, he understood that in the end, rationality could only explain so much.

The God Spectrum and You

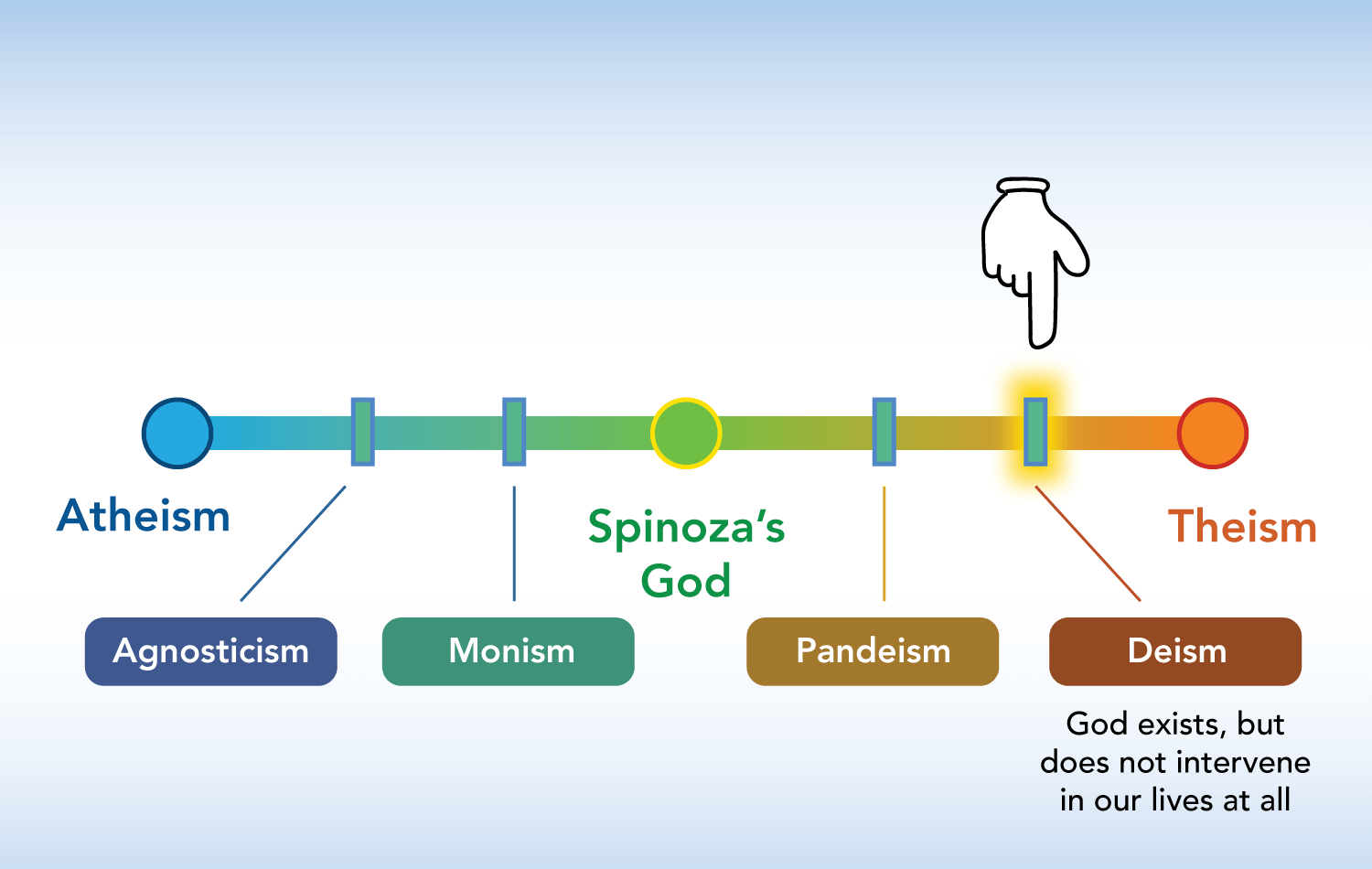

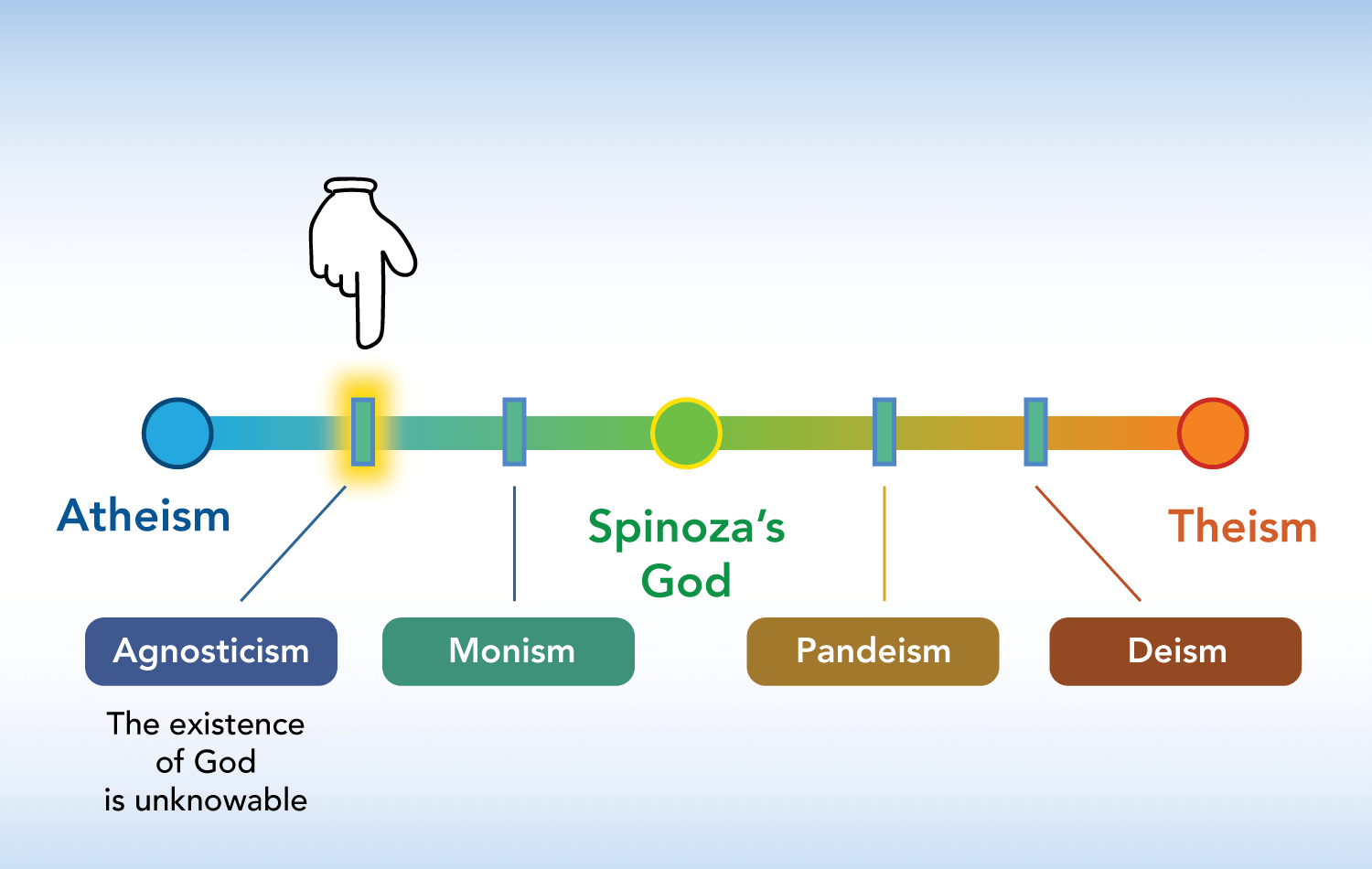

In an effort to make the God Spectrum more concrete, I wanted to map some key beliefs onto it to act as reference points. Here’s the result:

The tricky thing about this spectrum is that reason and imagination are not mutually exclusive. They often overlap with one another, as many of the belief systems on one side have qualities of the other. For example, a devout Christian can also believe in evolution. Or a physicist can believe in some higher power. It happens all the time.

But you cannot be both an atheist and a theist. You can’t believe in God while simultaneously not believing in him. While you might be able to cherry pick some of the underlying ideas and make them cohere, you can’t do that for the belief system as a whole.2

So when it comes to the question of “Do you believe in God?”, you can’t say “Yes” and “No,” even if that’s how you might feel. What you really mean with that type of answer is: “Perhaps, but I have to first clarify what type of God I’m talking about here.”

That’s what the God Spectrum is for. It spreads out the various views of God into a gradation of belief that makes them easier to identify.

If you don’t believe in an anthropomorphic God but feel that Being itself is imbued with something sacred, you might believe in Spinoza’s God:

If you believe in a God that listens to our prayers but is ultimately indifferent to them, you may be past the midpoint, but not fully immersed in the faith:

If you think all versions of theism are nonsense but can’t shake the inclination that something like God may be holding this universe together, then you’re here:

Regardless of where you are, the place you stand today may not be the place you stand tomorrow. Our conception of God is one of those things that tends to shift, depending on the people we meet and the things we experience. It’s not that our minds keep changing about God, but that our definition of God keeps getting revised.

The question of “Do you believe in God?” is one that caters to rigid certainty. The question of “What do you think of God?”, however, is one that allows you to update your beliefs as your experiences shift.

Belief is never a binary matter, as truth lives in nuance. By viewing the question of God as a spectrum, we acknowledge that reality, and continue revising our conclusions as our views expand over time.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Wherever you are on the God Spectrum, make sure to be flexible:

Thought Stop Signs: The Source of Lazy Thinking

For a closer look at belief systems, and a call to examine your own:

Do You Really Believe What You Believe?

When the mystery of the world is too great, remember that it’s not the world’s fault: