The Ultimate Guide to Visual Storytelling

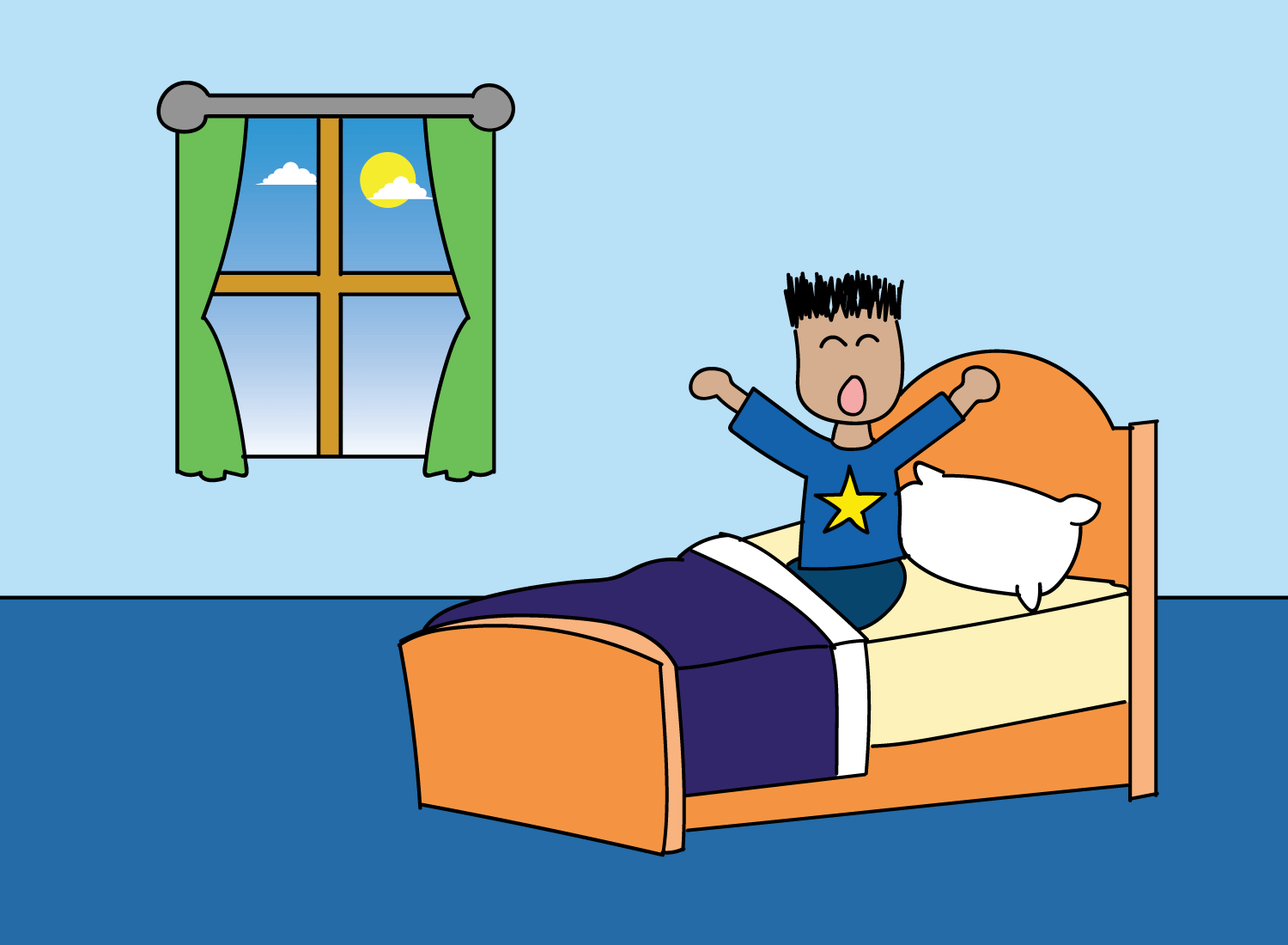

My earliest childhood memory was stressful.

I was about 5 years old, and it started with me waking up from an afternoon nap.

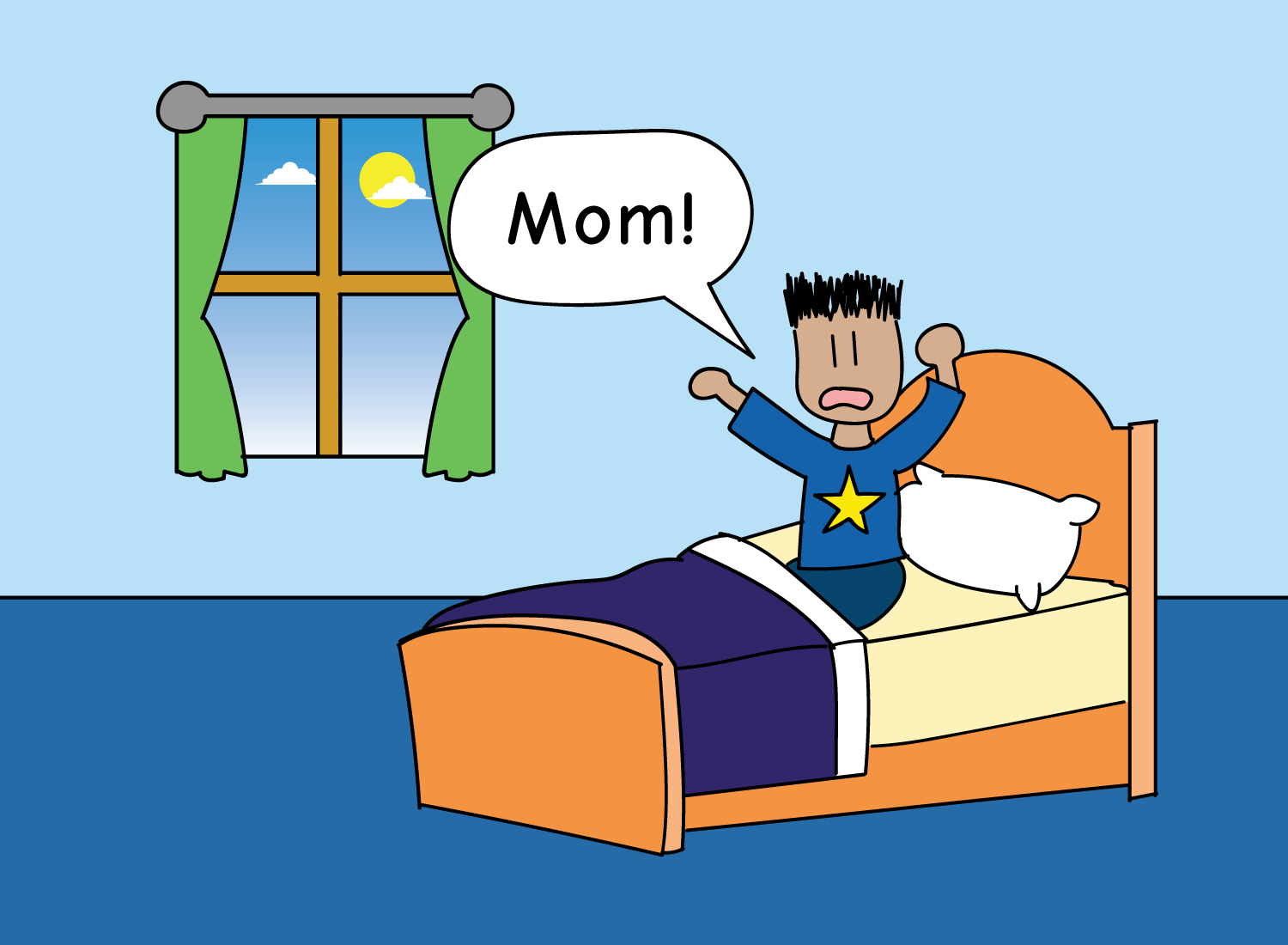

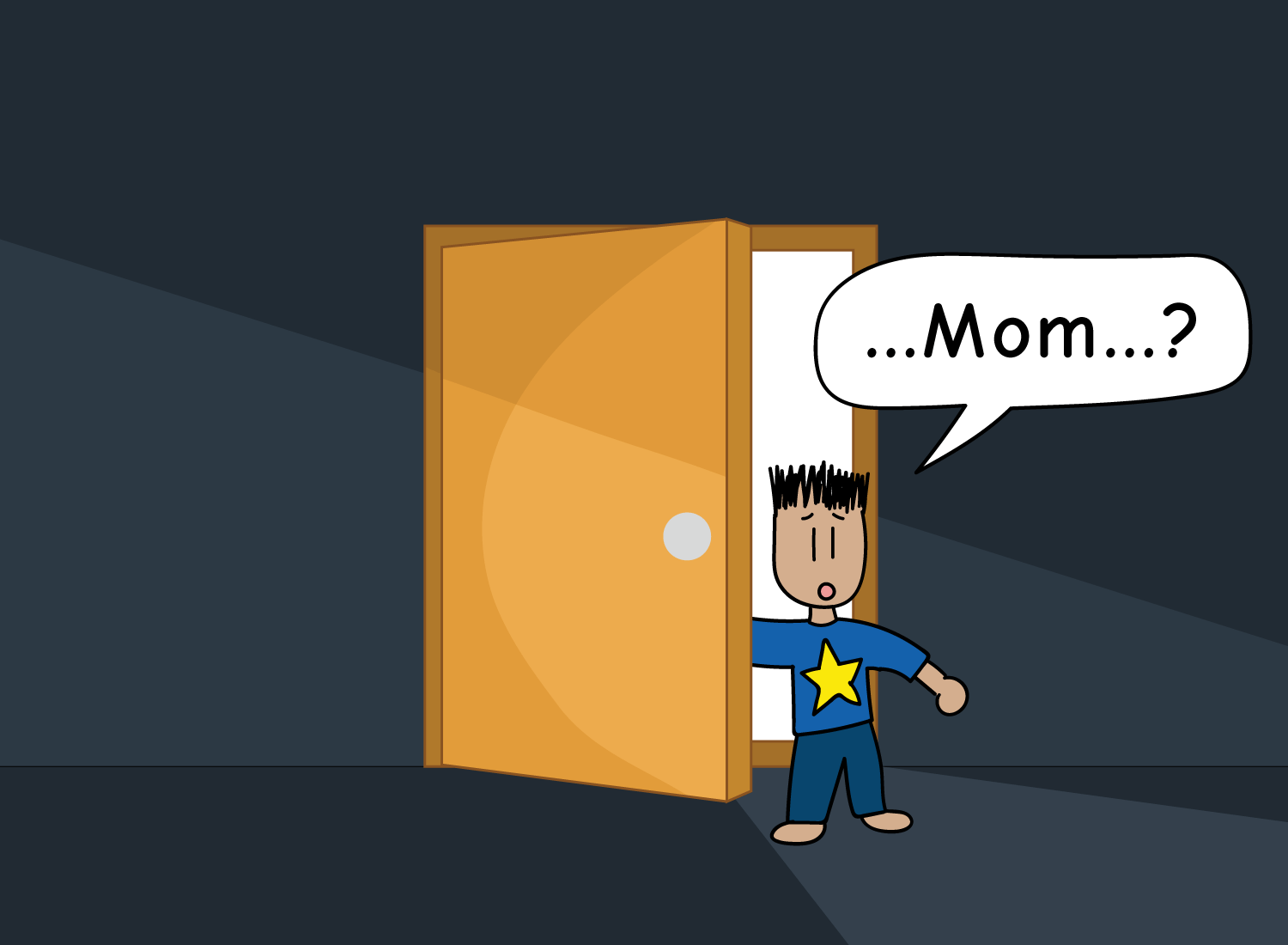

Since I was a child with many needs, the first thing I did was ask for my mom.

Historically in my past 5 years of existence, calling for her with a sniffly tone meant that I would see her relatively soon. Sometimes I’d have to call for her a few times, but never more than ten.

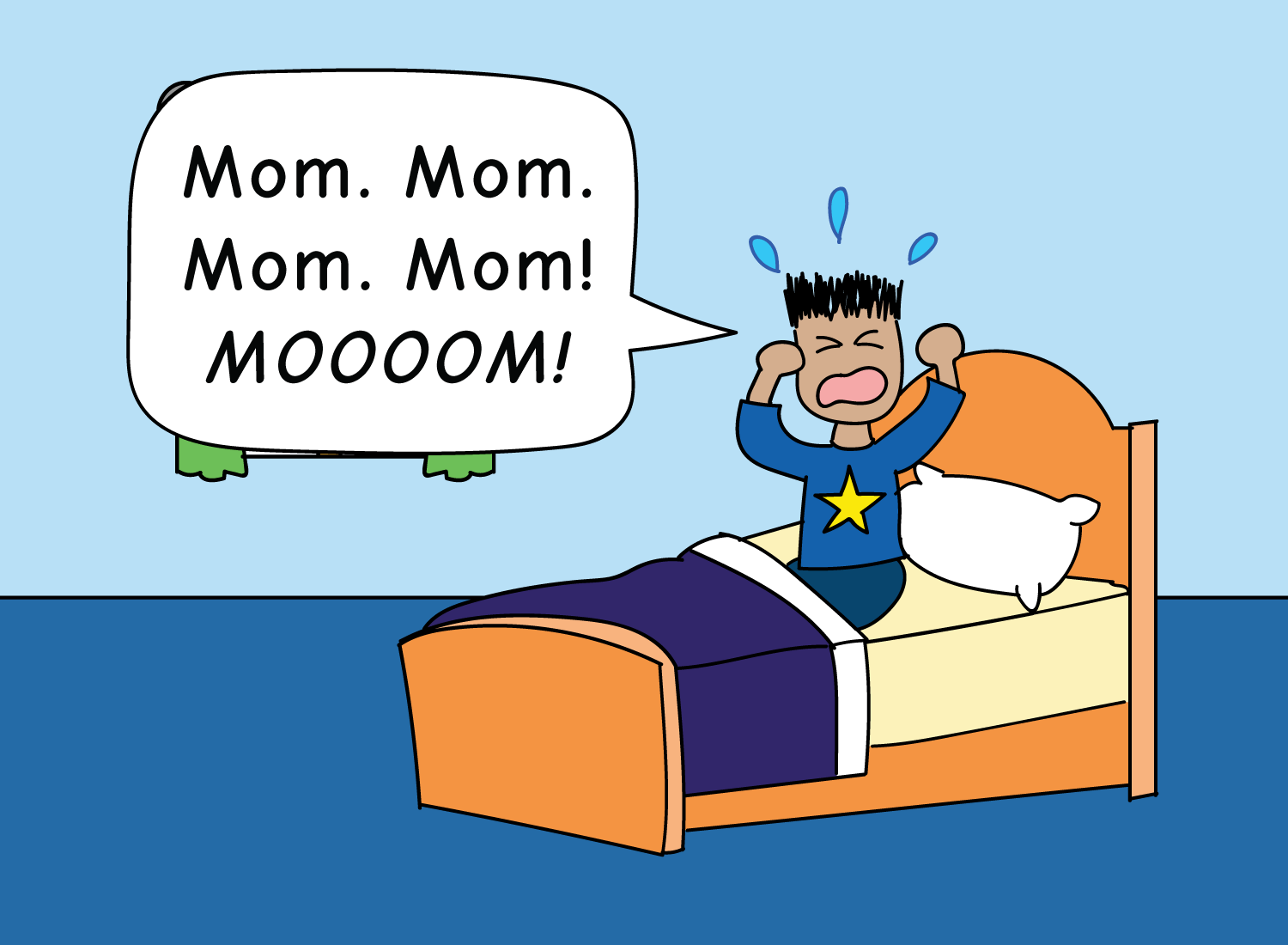

But on this day, I hit well over that number, and mom was still nowhere to be seen.

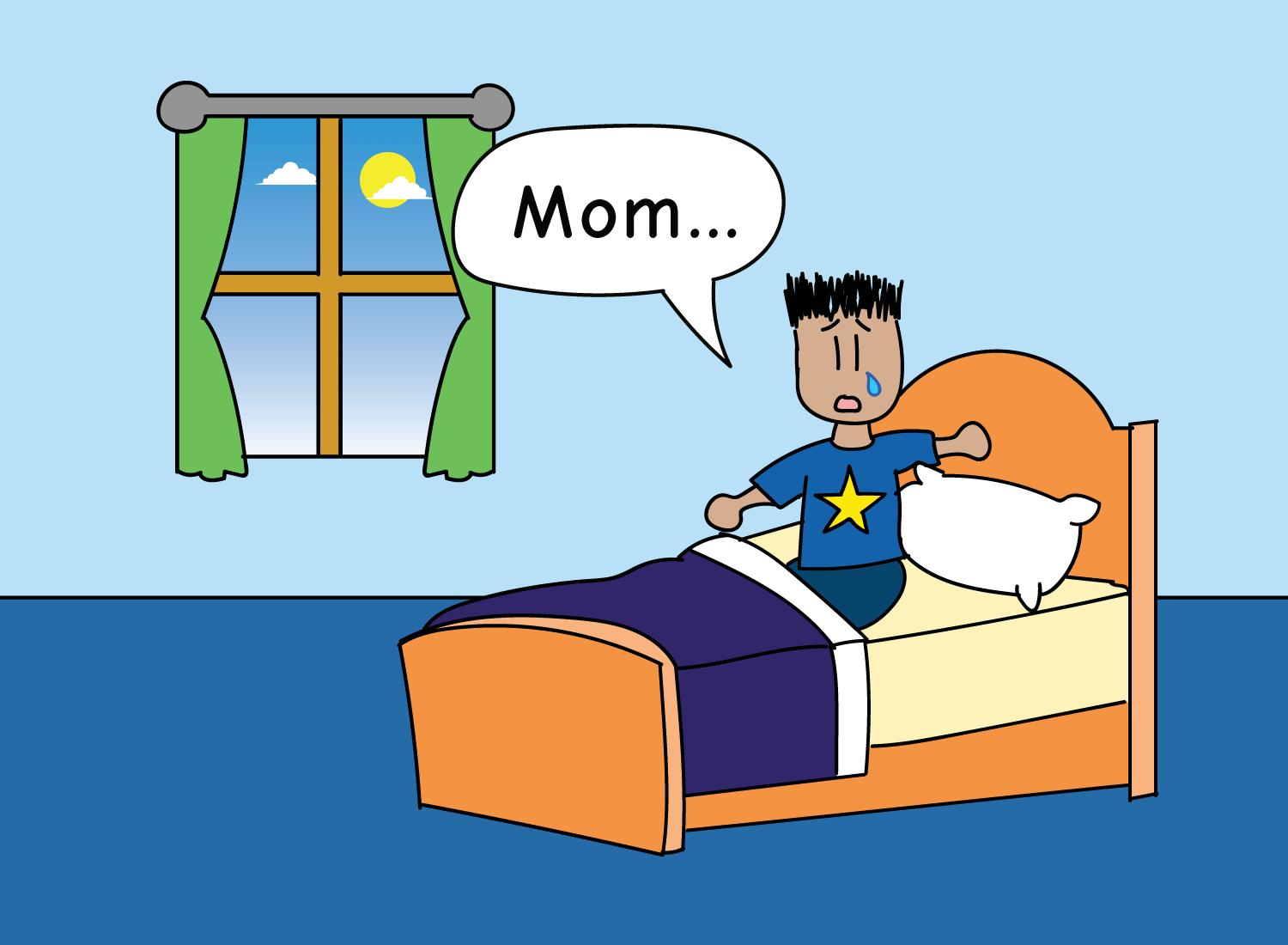

At that point, I got my ass out of bed, and ventured out to the other parts of the house. With each room and space I entered, I would seep out a whimpering call for mom, with each one becoming more hopeless than the last:

After hitting up every room, it started dawning on me that mom wasn’t here. My dad wasn’t here either. Not even my younger brother.

Everyone was gone.

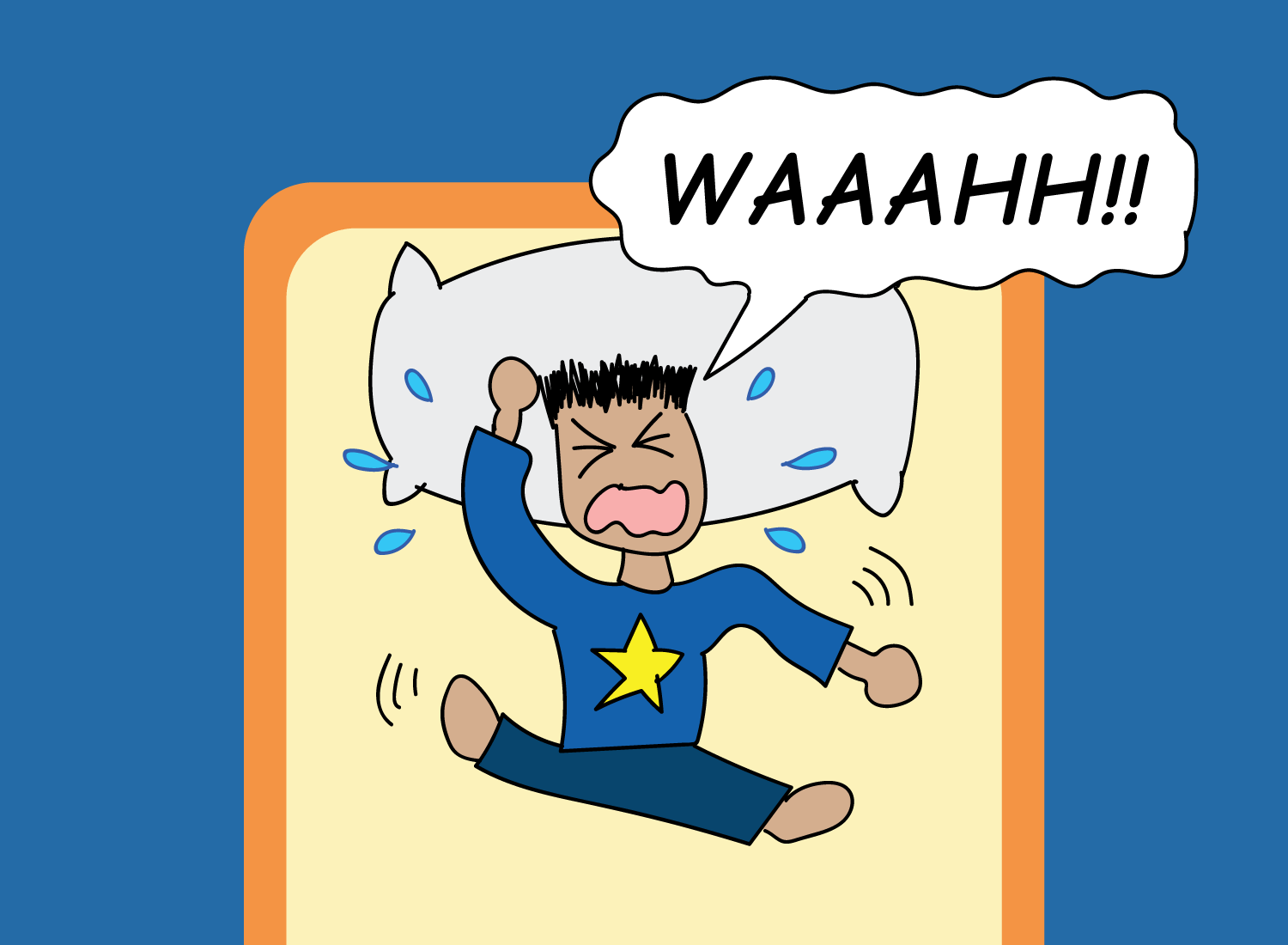

As this realization detonated in my brain, I slowly made my way back up to my bed.

Where is everyone?

Are they ever going to come back?

Am I here alone… forever?

With that final question, I let out the biggest sob ever recorded in toddler history. My tears mixed with nose mucus as this stream headed toward my mouth, making this experience even shittier. I pounded my mattress, made Chewbacca noises, and writhed around like a snake that couldn’t decide where to go.

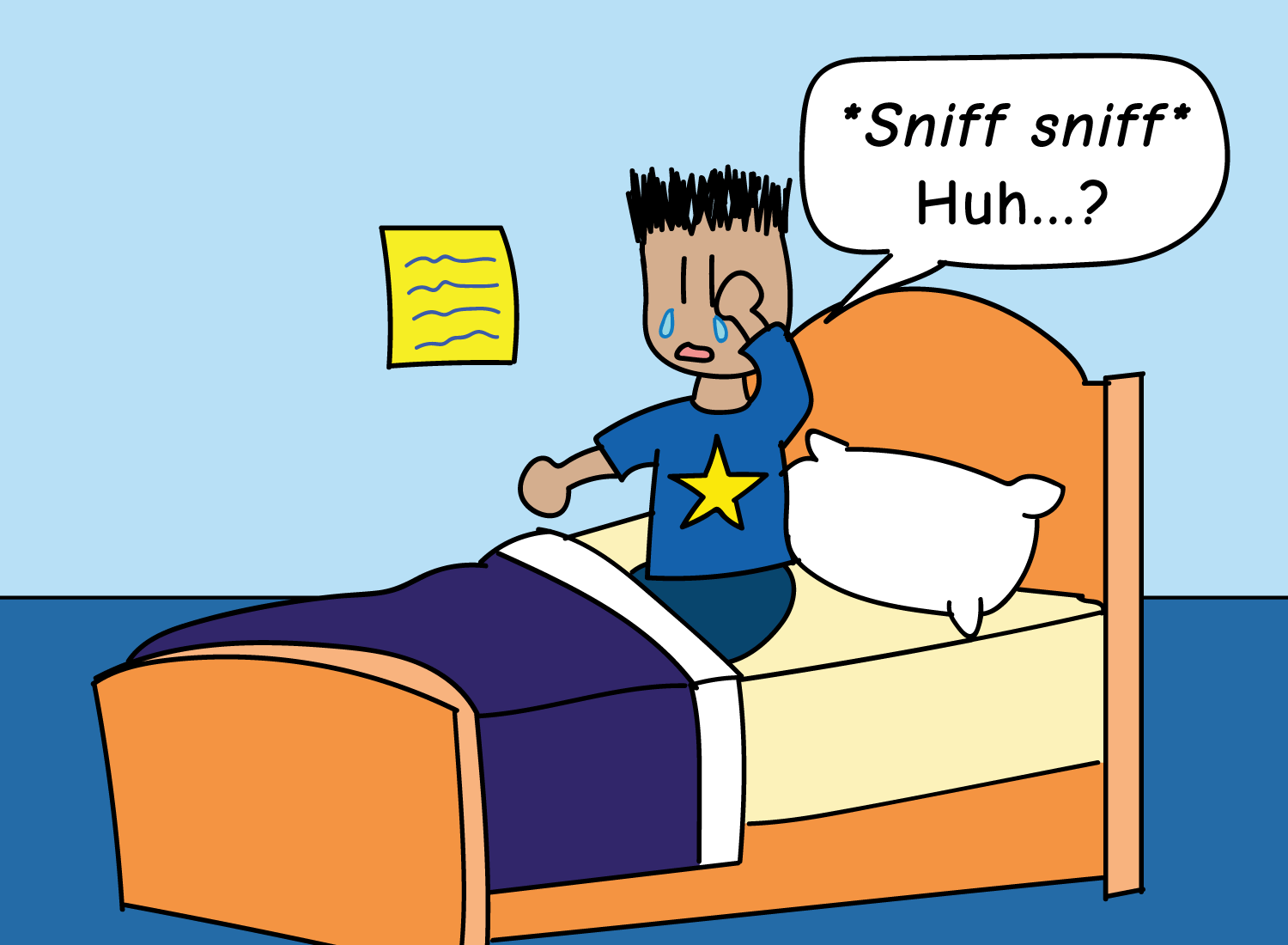

As the bawling continued, I briefly caught something in the corner of my eye.

It was a glimmer of yellow coming from the wall that was adjacent to my bed. I couldn’t quite tell what it was because my eyes were clogged up with sadness aqua, so I had to clear the eye ducts to see a bit clearer.

It turned out this yellow thing was a square, and this square had some handwriting on it.

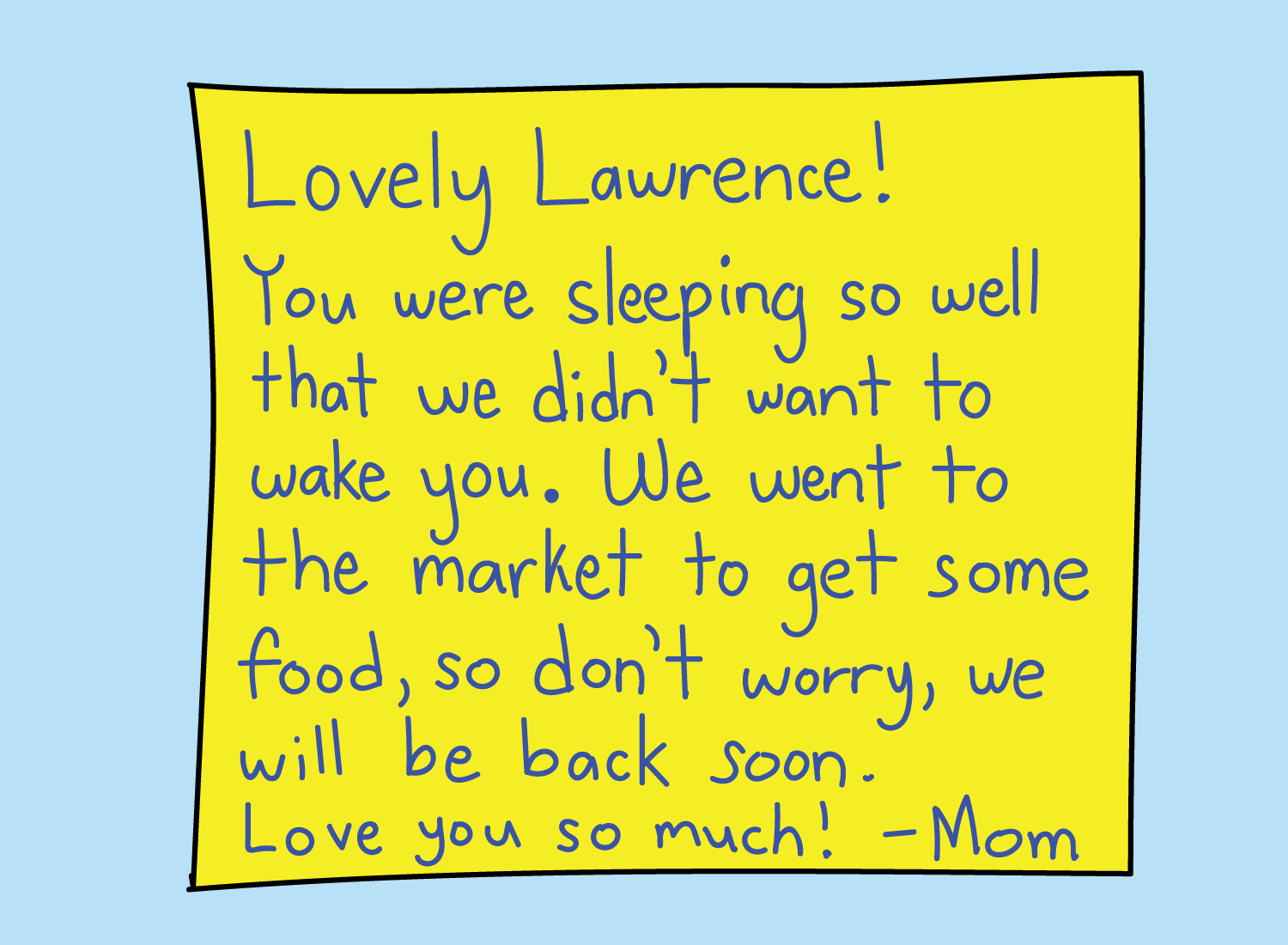

The Post-It note said something to this effect:

As I read those words, I sat there, utterly dumbfounded. Just like that, everything made sense, and the world was okay.

A minute ago, I was an uncontrollable, sobbing maniac. But after reading a few words on a tiny sheet of paper, I now had the peace of a seasoned monk.

I wasn’t going to be abandoned after all. I wasn’t going to be alone.

My family was coming back.

I didn’t realize it then, but it’s amazing to know how much power that little Post-It note had. On it was a message my mom knew I needed to read if I woke up while she was gone. She knew that those words would bring comfort and solace if I were ever in a state of fear.1

Whether she realized it or not, she was conveying a story on that Post-It for me. She wanted me to know that she only left me alone because I was in a peaceful state, and that of course she’d back because she loves me so much. If I was ever worried that she wouldn’t return, there was no need to be. She was going to come back.

She would always love me. Forever.

That short narrative arc was all I needed to calm me down.

My earliest childhood memory was scary at first, but through reading my mom’s words, it ended quite peacefully.

Come to think of it, at the young age of five, I experienced something quite incredible:

It was the first time I read a story that profoundly moved me.

The Case for Visual Storytelling

My name is Lawrence, and I’m a storyteller.

Not a writer. Not a cartoonist.

A storyteller.

It took me a while to realize this, but after creating ~50 illustrated posts on this site, I began noticing a pattern throughout them all.

The pattern has nothing to do with length. Some of them are super long, while others just take a few minutes to read.

It has nothing to do with popularity either. Some have been viewed an absurd number of times, while others barely register any traffic.

Rather, the pattern resides in something far more interesting:

The narrative structure I use for each post.

Ideas are powerful, but they are meaningless without a story to contextualize them. Truth without narrative is like music without rhythm. They both exist, but they won’t move you in any meaningful way.

It’s like the difference between:

(A) Hearing a friend proclaim that “life is what you make it,” and

(B) Going through a series of ups and downs for many years and truly realizing that “life is what you make it.”

Scenario A is a mere platitude, while Scenario B is deeply profound.

The job of a storyteller is to guide the reader along the nuanced journey of Scenario B.

In this post, I will outline the steps and processes I use to create the stories you see on this site today. While there’s no one formula I follow, there are general patterns and concepts that help guide the direction of these narratives.

But first, I need to clarify something.

As you can see, text is just one of the mediums I use to convey my ideas. The other are illustrations, which number well over a thousand on this site alone.

All in all, these illustrations have required thousands of hours of my time. If I didn’t do them, I likely would have published far more essays and posts, and been more prolific as a result.

However, these illustrations are central to the stories that I want to convey. They are not mere sprinkles I add to the cake; they are the cake itself. Without them, much of the central messaging would be lost.

So if I were to be more specific, I’m not just a storyteller.

I’m a visual storyteller.

Interestingly, that addition makes all the difference.

Within these two words are my keys to creative differentiation.

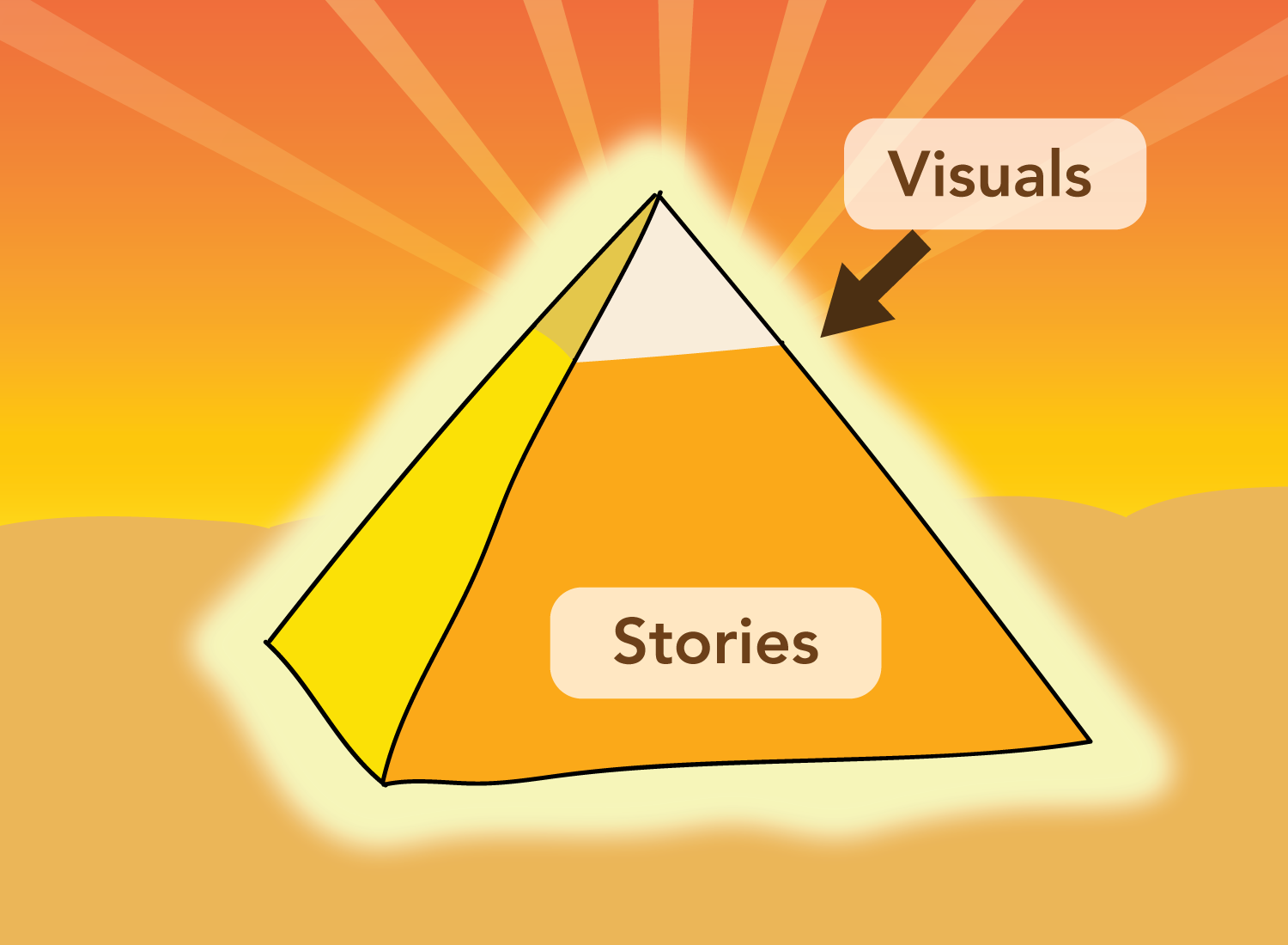

Stories are the fundamental units of any compelling idea. They are the individual blocks that make up the pyramids. Without them, no structure would exist.

But visuals are the colors that are incorporated to make those ideas memorable. They are the white limestone that gave the pyramids their radiance. Without them, the structure wouldn’t shine.

In today’s era of content abundance, adding in the visual component immediately adds a recognizable aesthetic to your stories. It simplifies concepts into something graspable, and it also provides a quality to them that only you can readily produce.

Multi-sensory experiences make journeys fun to navigate, and there is no better way to craft them than through the path of visual storytelling.

Fortunately, that doesn’t matter! The best thing about visuals is that they don’t have to look great to get the idea across.

If you’re using cartoon characters, you could quite literally use blobs, square heads, stick figures, anything that takes less than 10 seconds to draw.

If you’re using diagrams, you could just whip up something in Excel or Figma and use that.

Visuals are valuable because they augment the text; they provide a new frame for the reader to see the idea through. It doesn’t have to be beautiful, it just has to summarize the general idea well.

So now that I’ve sung the praises of visual storytelling, how exactly do you do it? What are the steps required to put this craft into practice?

I’ve distilled the whole process down to four essential steps:

1. Select an idea

2. Define the Problem and the Takeaway

3. Create the Visceral Journey

4. Simplify the message visually

The first three steps are all about good storytelling, while only the last step is reserved for the visual component. That’s because without a good story, an incredible illustration is next to meaningless.

Keep this in mind as we progress through these steps. The ability to construct a strong narrative is the top-most priority, and everything else acts as a force multiplier of that goal. Stories are what move us, and their anatomy is what we need to truly understand.

But all stories – from money to monism – started with humble beginnings.

At first, they were nothing but loose seeds of disjointed ideas.

Step #1: Select an idea

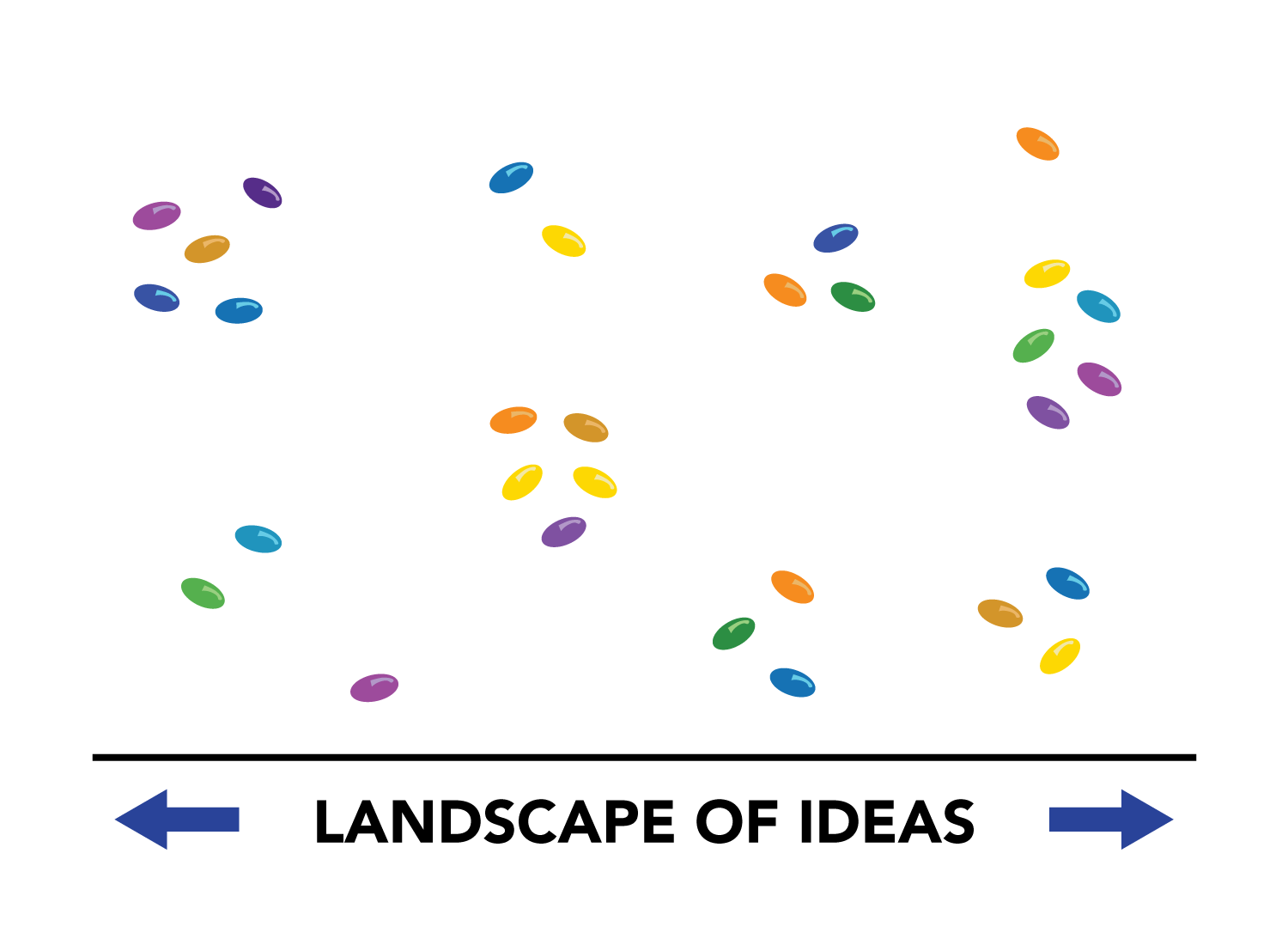

In my two–part series on knowledge, I imagined ideas to be little seeds that exist all around us:

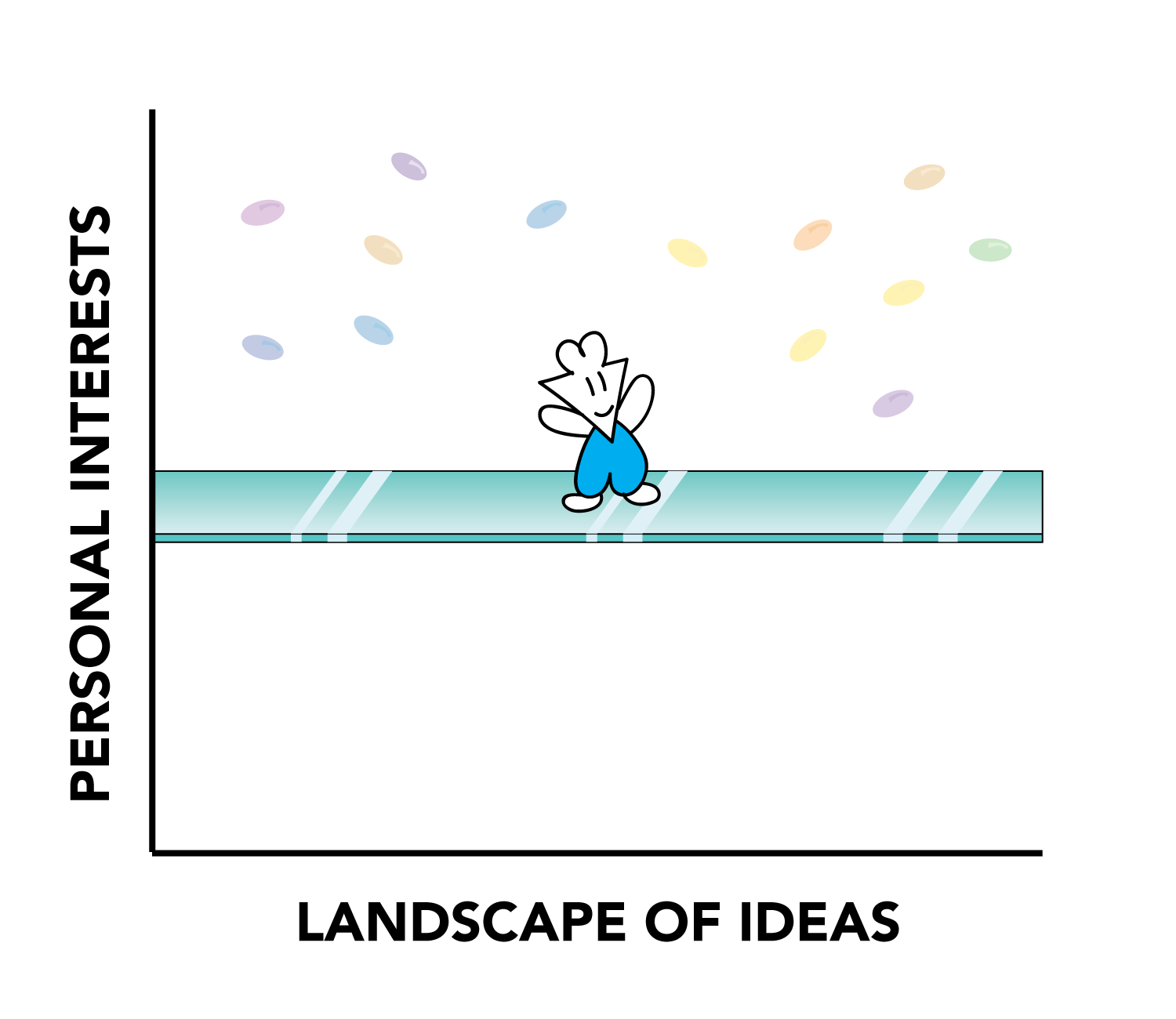

These seeds are scattered across a vast Landscape of Ideas, where they are passed around from person to person, organizing themselves into clusters based on their resonance.

This is the playground we find ourselves in any given moment. So many seeds, so little time. At first glance, the whole thing can be overwhelming.

How do I choose an idea to write about? Which one of these seeds should I invest my time in? Is there anything new for me to add here?

Fortunately, we are able to narrow the landscape down through the addition of another axis:

The range of our personal interests.

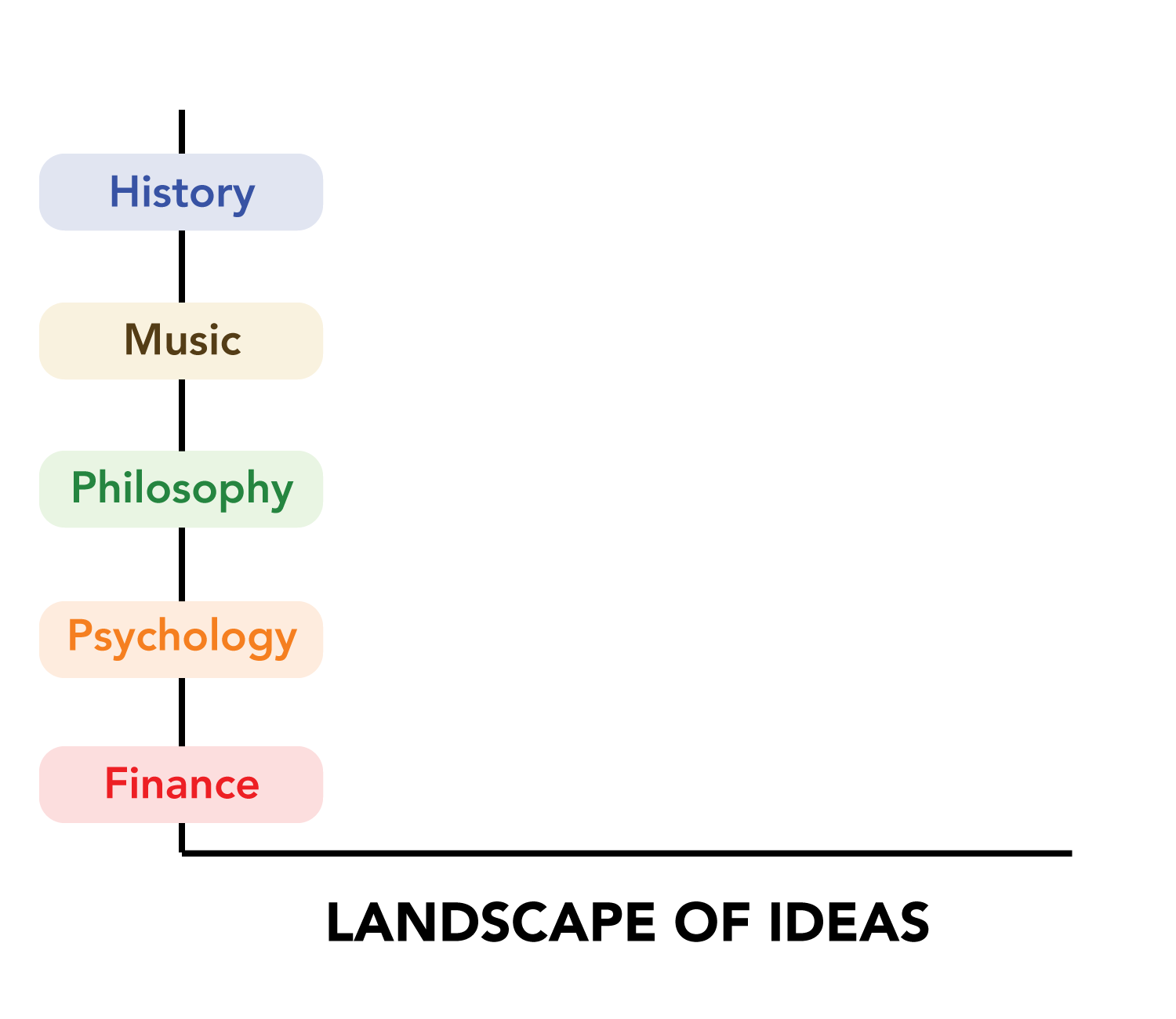

Each point on this axis represents a topic or subject that piques our interest. Here’s an example of mine:

When we engage with any particular interest, something cool happens:

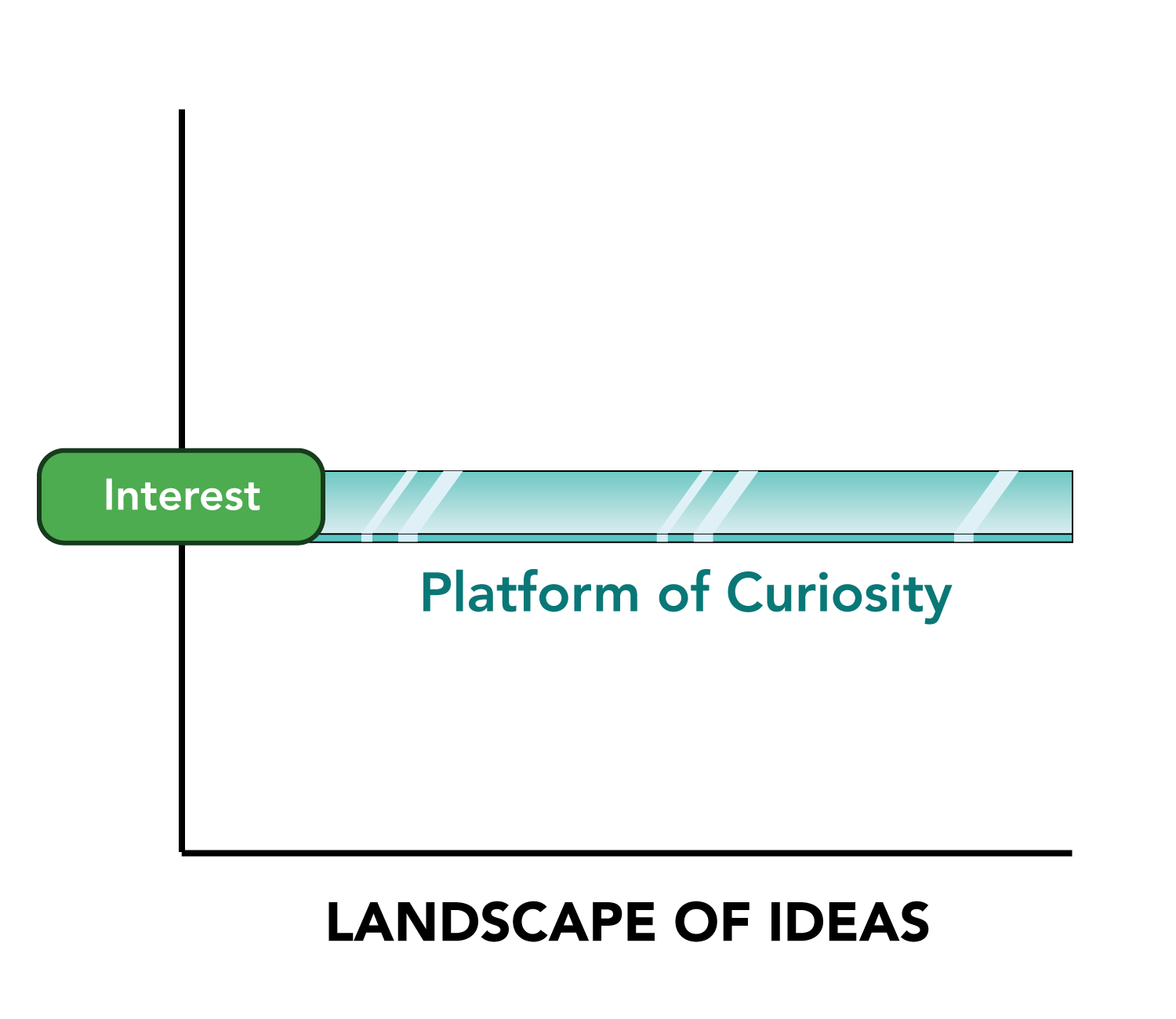

A platform of curiosity appears from that point of interest to extend across the landscape of ideas.

The beautiful thing about this platform is that there’s a magnetism to it. When your curiosity is opened, the awareness of your creative spirit allows ideas in this space to draw closer to you.

As long as you keep your curiosity alive, you will be able to access the seeds that exist along this platform you traverse.

So now that you have access to these seeds, how do you actually find the ones you want to tell a story about?

There are three ways you can do this:

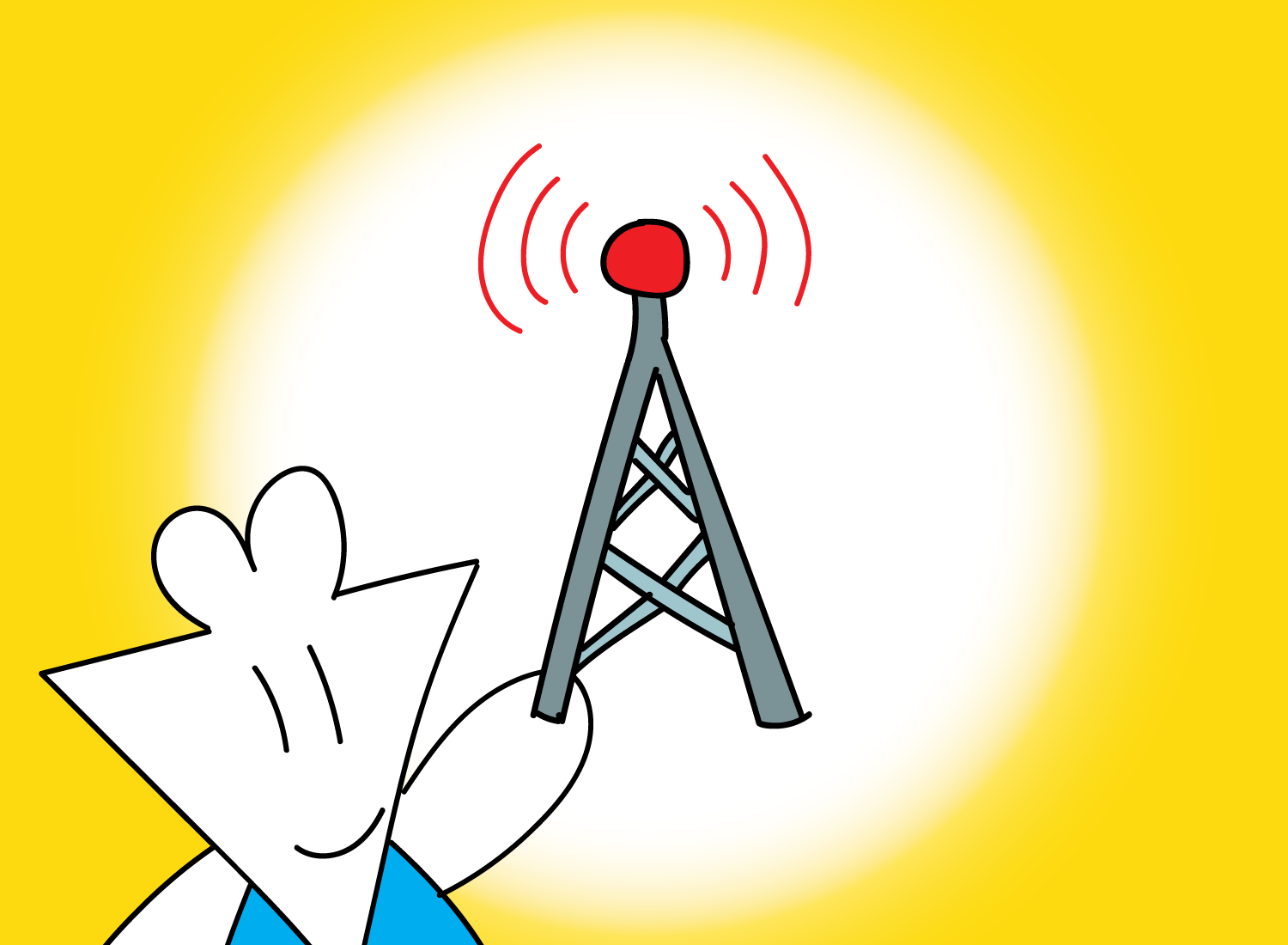

(A) By holding up an antenna,

(B) By building a live feedback loop, or

(C) By dipping into personal experience.

Let’s go through each one now.

(A) The Antenna

An antenna is a one-way receiver of ideas. When you lift it up into the landscape, information about your interests will be drawn to it, and new ideas are discovered as a result.

Today, antennas come in various forms. They are the podcasts you subscribe to, the YouTube channels you love, the blogs you read, or the books that line up your shelf. Anytime you engage with these information sources, the antenna picks up that knowledge, and transfers it over to your mind.

If you’re ever short on ideas, hold up the antenna. Use your personal tastes to guide you to a thinker who interests you, and delve deep into the work that he or she has created. This will reliably get your intellectual gears spinning, and seeds will naturally float on over.

However, an antenna is limited because it can only receive ideas. You can’t have a discussion with a podcast host or exchange thoughts with an author that died long ago. Antennas are great at soaking in information, but bad at interacting with it.

This is where feedback loops come in.

(B) Live Feedback Loops

When you exchange ideas with another person, a beautiful thing happens.

Your seeds interact with their seeds, and if the conversation is especially good, they fuse together and a new hybrid seed develops.

This resulting idea is called an epiphany.

Epiphanies rarely come about on your own. Humans are social animals, and there’s something about the live exchange of thoughts that is crucial to the progression of the intellect. After all, education itself is founded upon the principle that there’s a live teacher present to challenge what you know.

When you present your ideas to others, you create a playground where new concepts can spontaneously develop. You will be made aware of something that was once foreign to you, which will only heighten your curiosity in turn.

If you want to see how your ideas tie in with another person’s current experiences, put down the antenna and call someone instead. Bounce thoughts back and forth. Share what you’ve learned. Listen to how it relates to what they know.

If anything, you’ll see if your worldview is relevant to another person’s own experiences. Oftentimes, what is pertinent to you is negligible to another. Having a conversation will help you see how your perspective spans across various life events.

Because when it comes to great storytelling, a connection to personal experience is perhaps the greatest asset of them all.

(C) Personal Experience

Information abundance is good for curiosity, but bad for storytelling.

Having instant access to any topic of interest is a godsend for avid learners. You are always just one Google search away from anything you want to know, and that’s an incredible tool.

However, this has made us reliant upon the opinions of others for everything. Whenever we have an idea, we feel the need to validate it with someone else’s words. We think we need quotes to legitimize our thoughts. Research papers to justify our intuitions.

This all makes for bad storytelling.

When someone enjoys your stories, they do so because they like the unique way in which you tell it. They don’t want to read the same quotes from the same psychologists that thousands of other people keep referencing. They like the way you frame your insights, and the interesting manner in which you deliver them.

This is why the best ideas come from the well of personal experience.

You’ll notice that I started this post off with a personal childhood story. This was intentional. I wanted to ground you with the sense that this post would be a reflection on my own experience with storytelling, and not anyone else’s. I’m not going to be citing research, nor will I be quoting anything from Joseph Campbell.

This was going to be about what I’ve learned, and what I’ve experienced.

Don’t shy away from the things that make you who you are. We don’t need double-blind psych studies to validate what you know to be true.

Step #2: Define the Problem and the Takeaway

Okay great. You have your idea.

However, having an idea doesn’t mean that you have a story. An idea gives you a topic, but now you must build a narrative that actually makes that topic interesting.

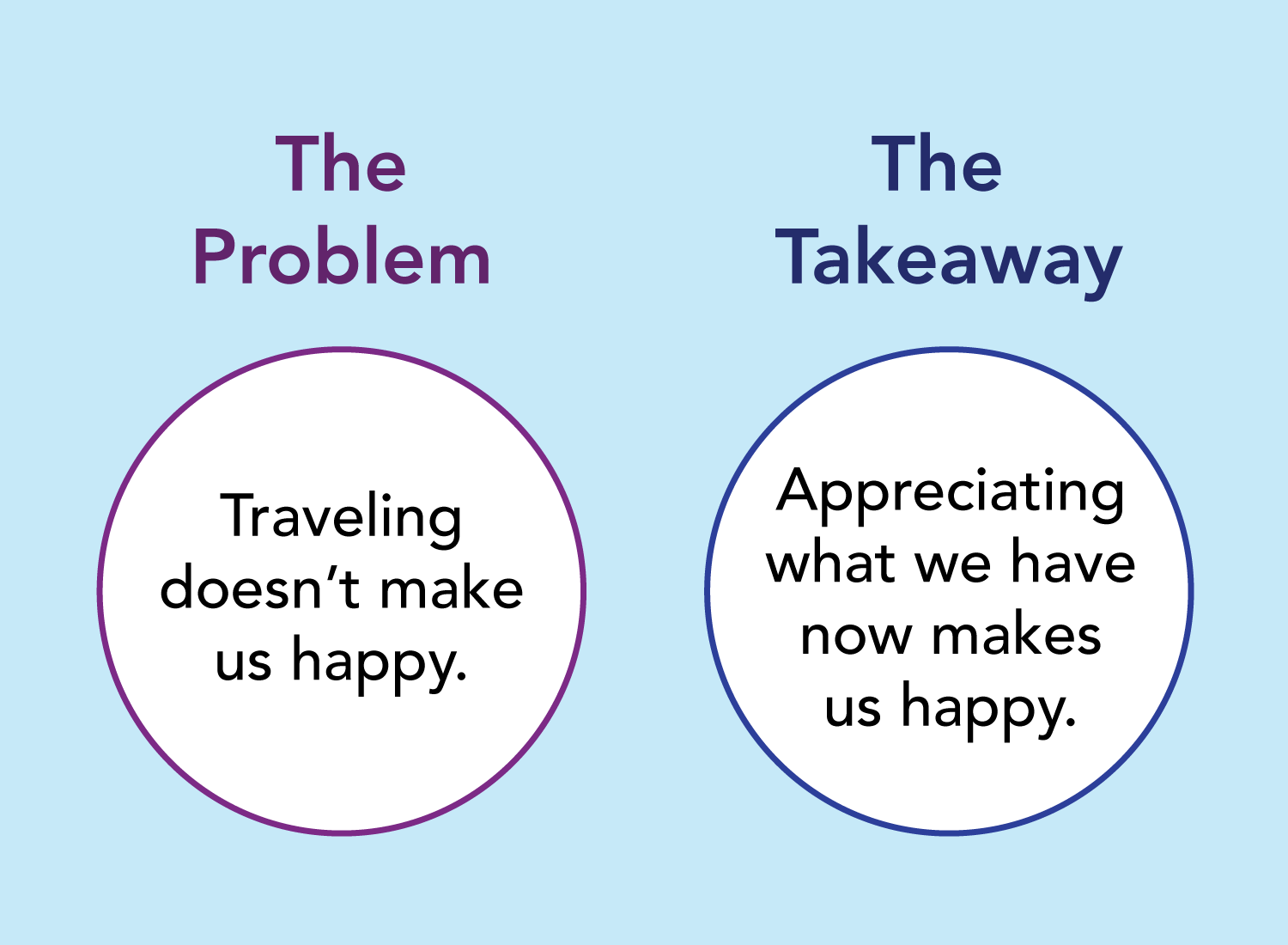

Yes, but fortunately, the initial step to crafting a compelling story is easy. All you must do is populate the following two bubbles:

That’s it.

Every good story has a problem that needs to be solved, and an ultimate takeaway. Those two things are the cornerstones of every narrative, and drive the overall messaging of any tale.

To make this exercise concrete, I will use one of my posts (Travel Is No Cure for the Mind) as an example.

For this story, here’s what it looked like:

Pretty simple, right?

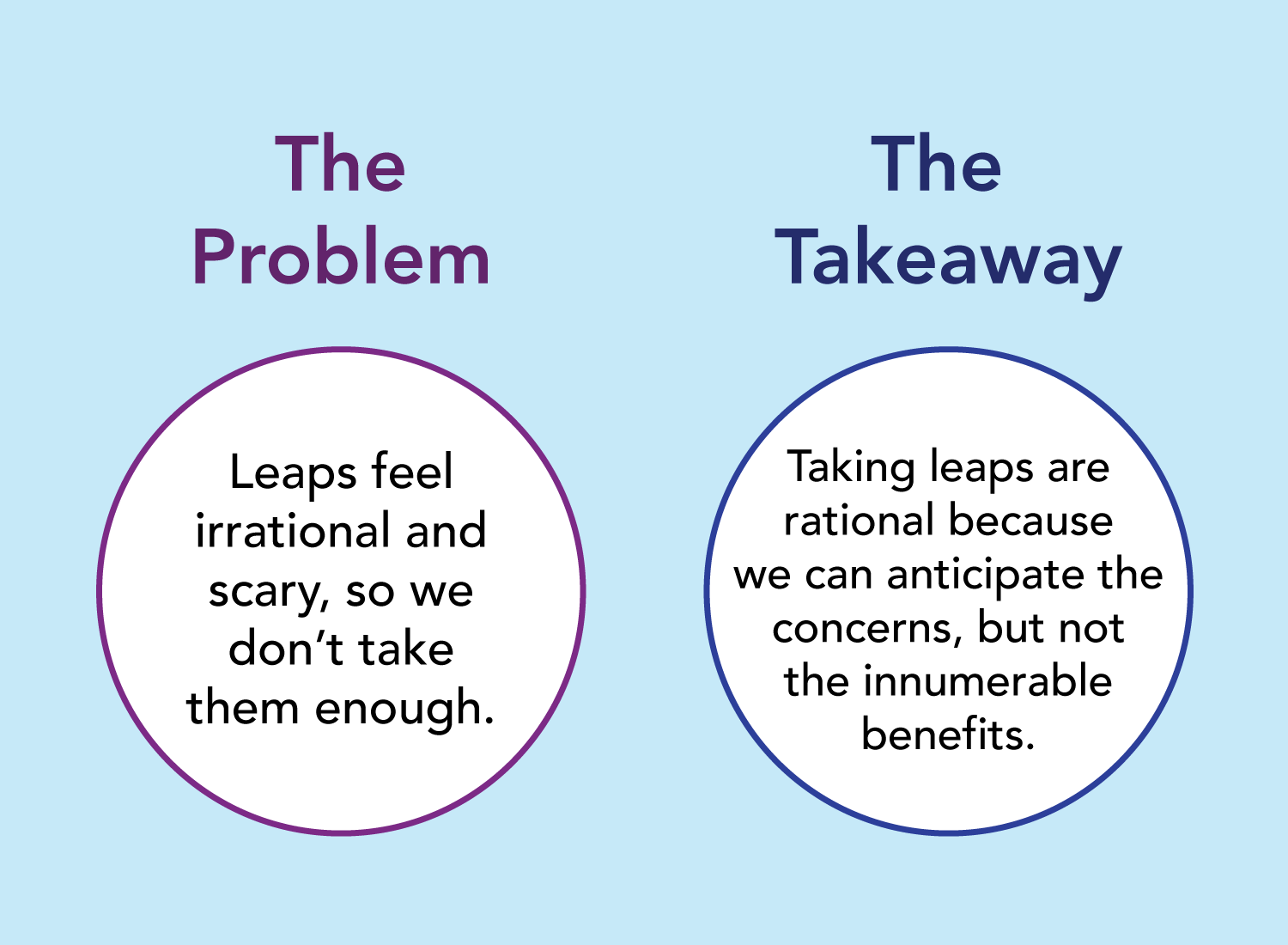

Let’s do another one (for The Day You Decided to Take the Leap):

It’s a simple exercise, but a powerful one. Instantly you’ll know what you’re trying to say in your story. There’s no confusion as to where you want this to end up, so you limit your chances of meandering to an empty conclusion.

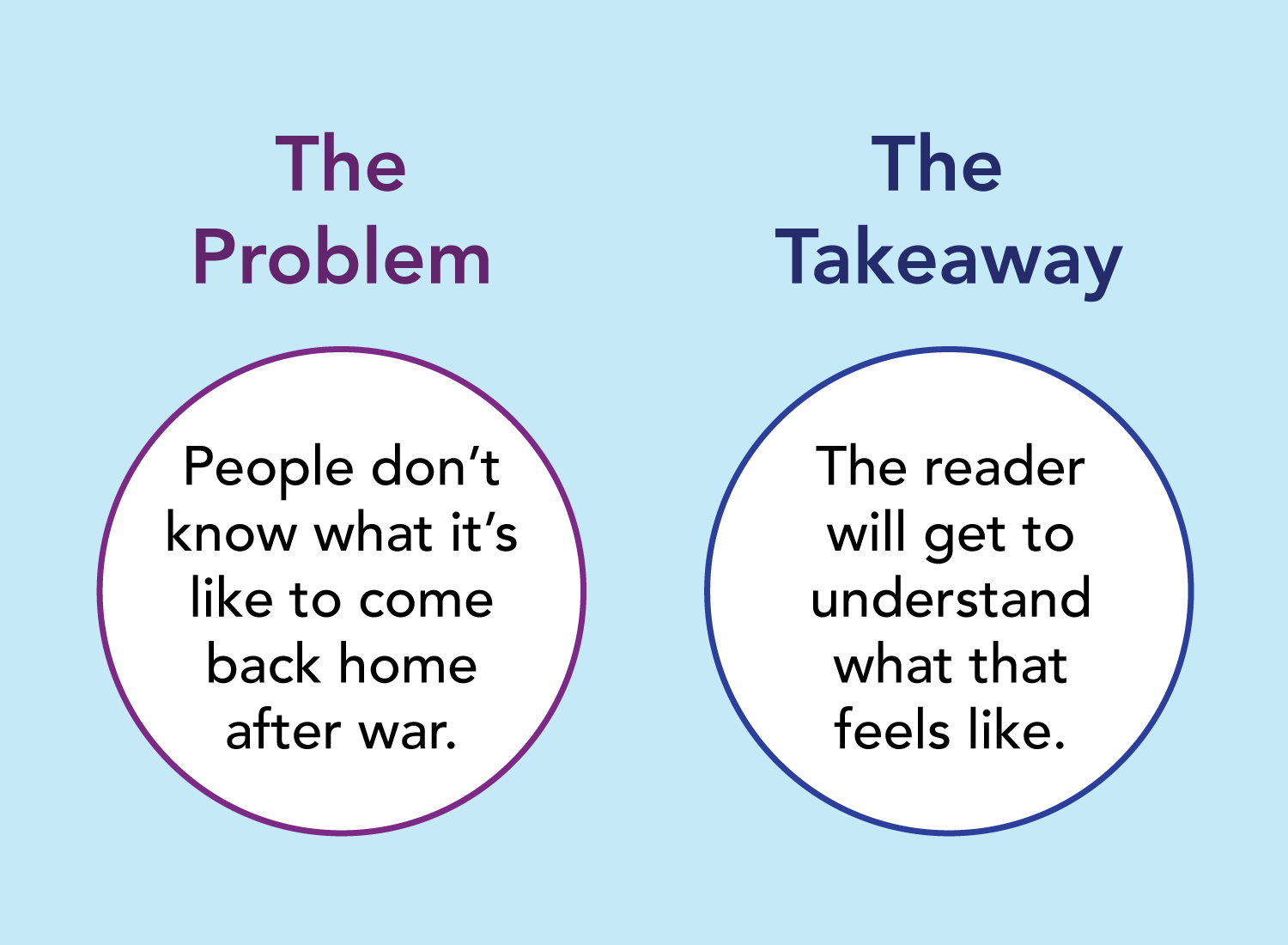

Additionally, by defining the takeaway, you’re also setting a purpose for your story. Some stories don’t have an educational takeaway; they just want you to understand what it’s like to be the narrator:

By defining the conflict and the resolution, you have set a basic roadmap to follow. Now that we have these goalposts in place, we can start crafting the journey itself.

Step #3: Create the Visceral Journey

Before I begin, we need to go over the difference between a story and a message.

A message is terse. Brief. It gets straight to the point, and leaves no room for digression.

A story is visceral. Fluid. It brings you along a convoluted path, and takes you to places where the destination may feel unknown.

Some writing must be framed as a message. Memos, emails, and investor letters are a few examples here. You say what you need to say, and move on.

Stories are not messages. You do not go straight to the takeaway, and have the reader move on with life. No. Instead, you want the reader to experience the entire arc that leads to that final takeaway. You want them to feel all the uncertainties that come with that exploration. All the epiphanies that emerge through dealing with that uncertainty.

Your job as a storyteller is to create the Visceral Journey. To create an arc that makes the reader feel as if she experienced everything herself. It is through this narrative that the takeaway will resonate most.

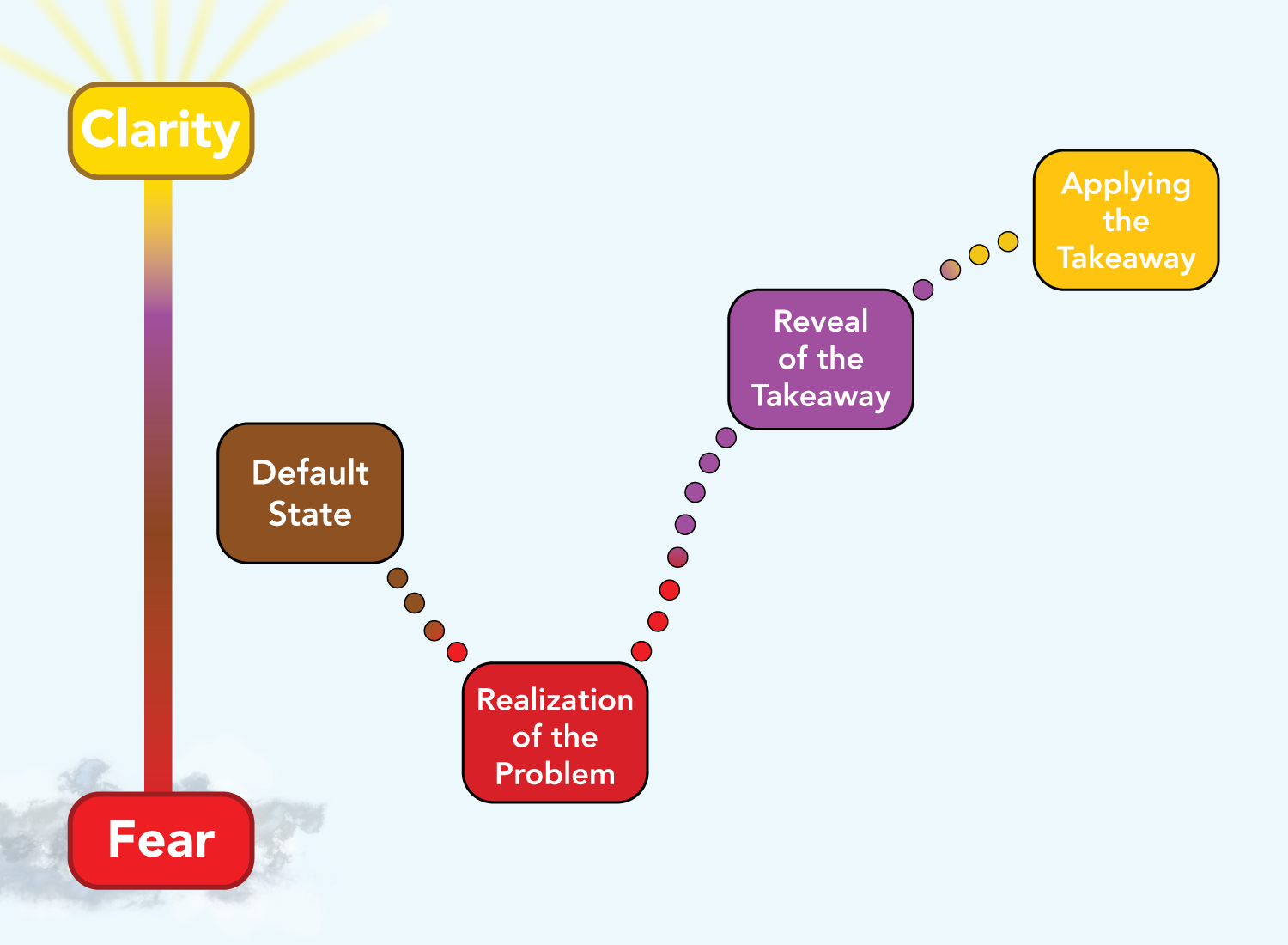

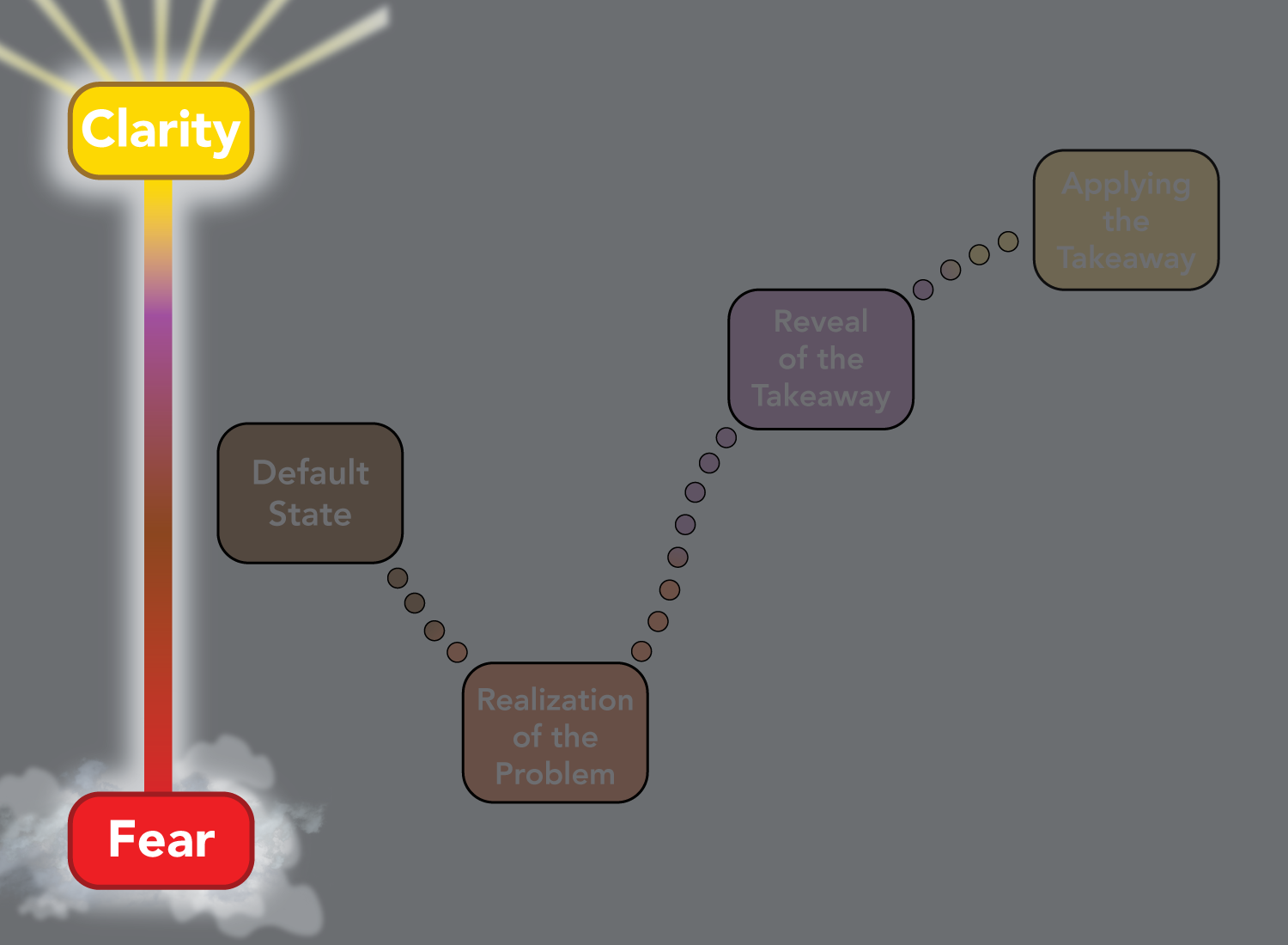

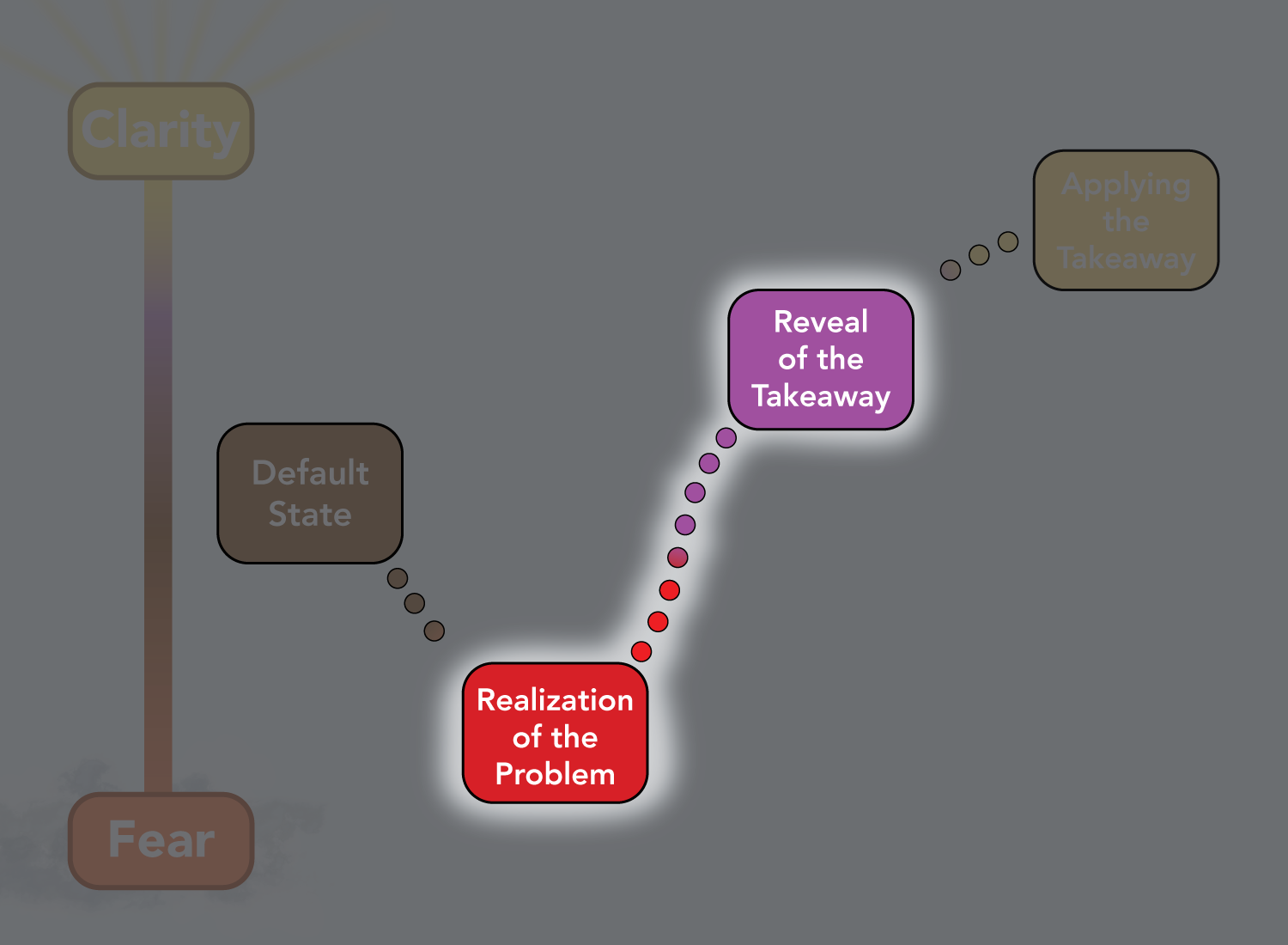

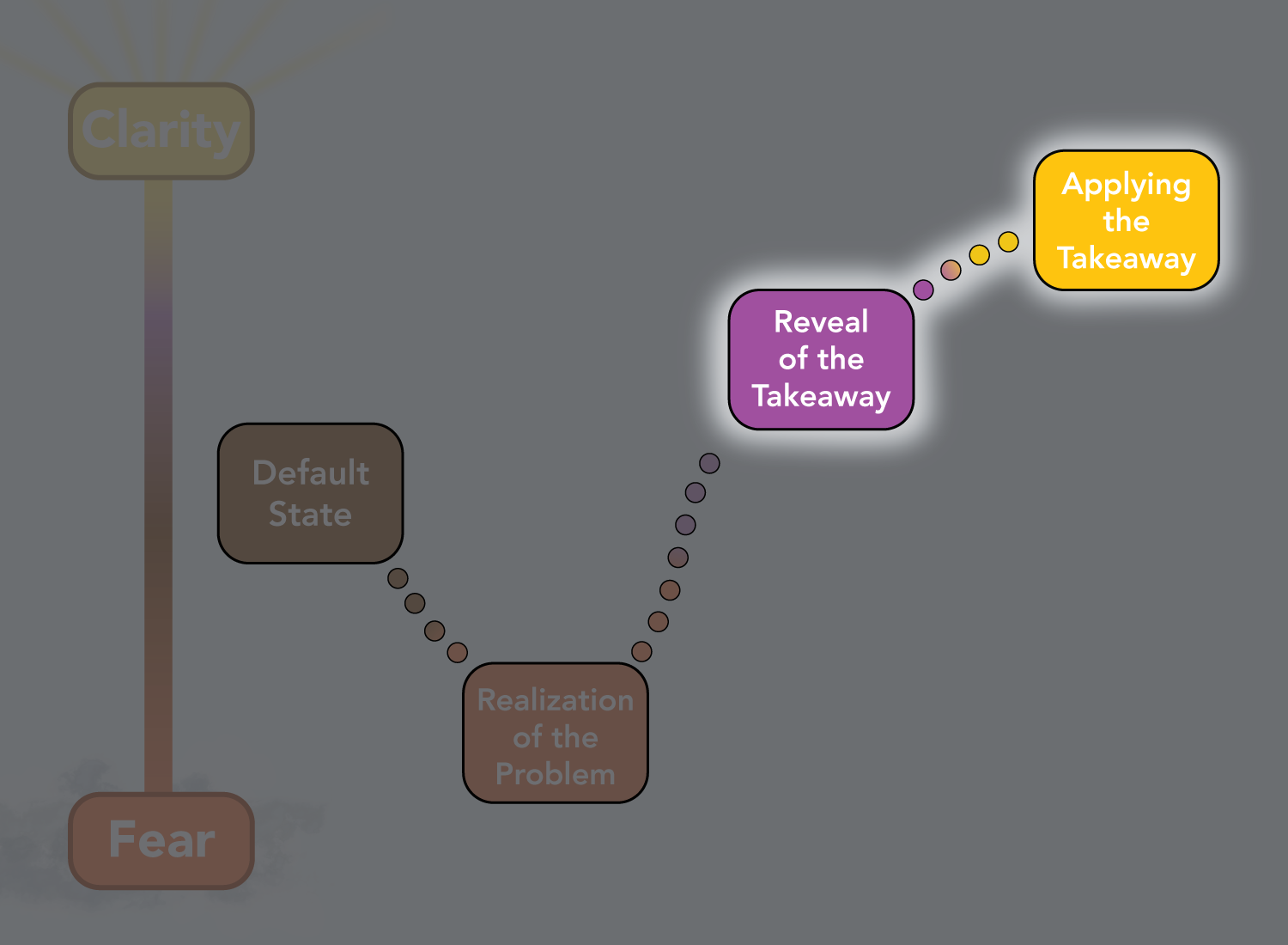

Here is the journey’s arc in its full glory:

I’m going to walk through each of these components, but first, I want to address the axis we are using to gauge our place within the narrative:

When I say fear, I’m not talking about being scared or horrified. We’re not talking ghosts and zombies here. By fear, I’m referring to the tension that arises when you realize that a better version of yourself is just out of reach.

For example, self-doubt is the fear of failure. It’s the inability to accept failure as a natural part of the process required to improve your outlook on life. If you were able to overcome it, then you would be fearless in your pursuit of the things that matter most.

Restlessness is fear of the present moment. It’s the inability to accept that everything is okay as is, and that you don’t need to look ahead for the things you really want. If you were able to overcome it, then you wouldn’t keep trading in the “now” for some imagined future.

Fear is the foundation for any substantive problem. Every compelling story introduces some fear we have, and then attempts to move the narrative toward the domain of clarity.

Clarity is where you understand what it takes to be a kinder and wiser version of yourself. That’s all it is. If you look at the greatest stories told over the course of human history (whether mythological or not), all of them move along this spectrum in a manner that eventually lands on a higher plane of thought.

Fortunately, you don’t need to write an entire book to move along this arc. It can be condensed into one essay or blog post, and I’m going to show you how to do just that.

(A) Building To the Realization of the Problem

As you craft the Visceral Journey, this is the most important thing to remember:

Have the reader walk along the journey of discovery with you.

Don’t assume that the reader knows what you know. Rewind back to the beginning, and start over again. Make the whole experience human, and create a path that carries the ebbs and flows you felt when you first thought about it.

Keep this in mind as you introduce the central problem of your story.

Let’s say I completely ignored this advice and started my travel post this way:

Uh… Okay.

That sounds mildly interesting, but it certainly isn’t captivating. It just sounds like I’m a wanna-be contrarian who wants to stir up the pot a little. There’s zero emotional resonance. It’s flat.

That’s because I haven’t taken my reader along the journey to help her come to that realization herself. I’m just taking my worldview and throwing it at the reader, hoping that it sticks.

Don’t start by throwing the central problem at the reader right away. That’s just not how life works. Problems emerge after we experience a sequence of events that lead up to the issue at hand, so you want the reader to feel that same burgeoning awareness herself.

One way to do this is to first paint a default setting that the reader can relate to. You can introduce a situation that isn’t very exciting, but is interesting enough to keep their attention. This grounds the reader in a familiarity that we can build upon as the problem is introduced.

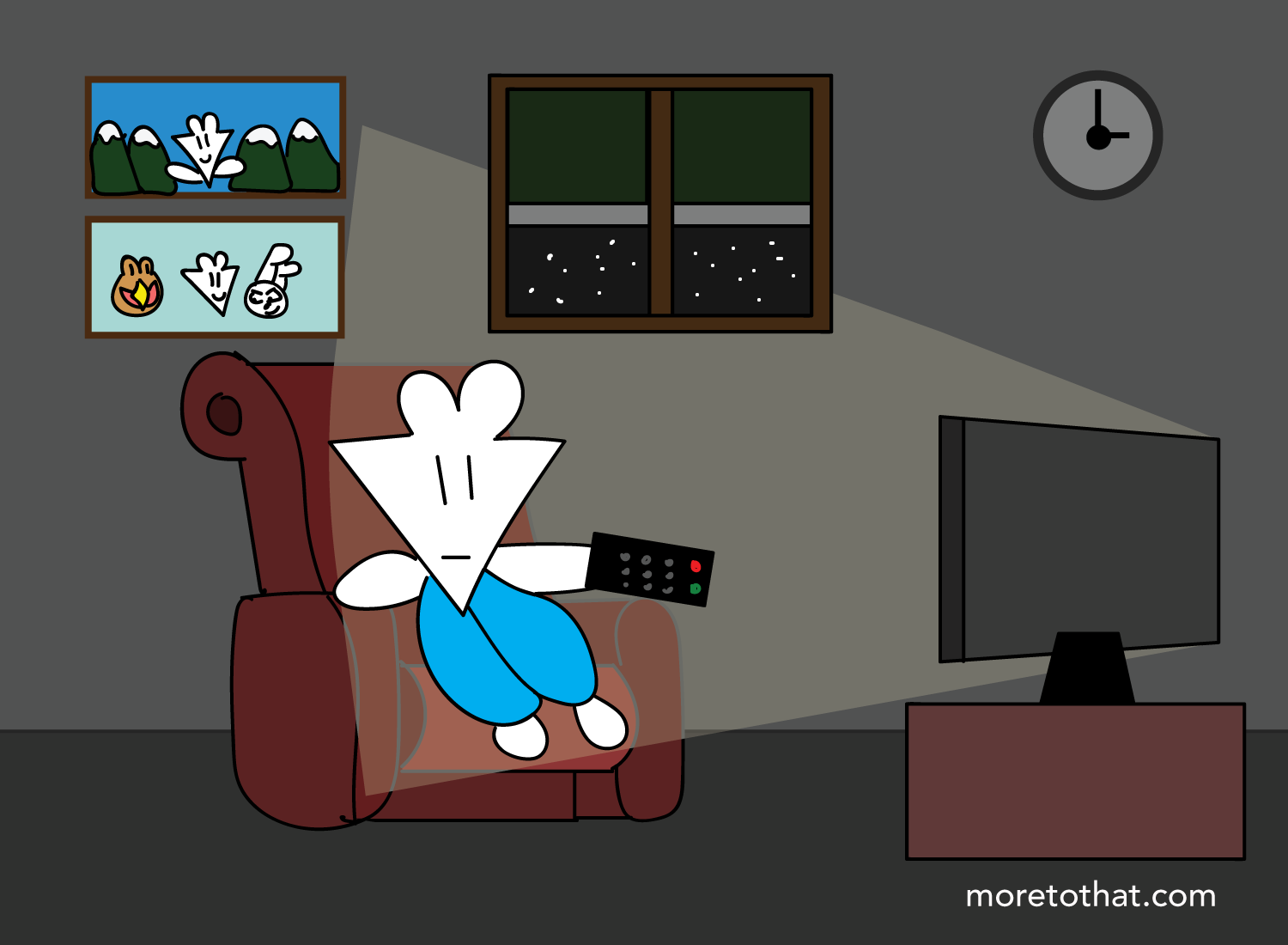

I did this in the travel post by starting with this simple sequence:

At this very moment, you may be here:

Or you may be here:

Or here:

But most likely, you’re probably here:

It’s light-hearted and relatable. It grounds the reader with the sense that we all have normal, everyday events we follow in our lives. But soon, I can introduce how this makes us feel restless, and how we begin to seek answers in faraway places instead.

Another effective way to introduce the problem is by telling a personal story of your own. I started my self-doubt post by telling the reader how badly I struggle with it. I started my money and identity post by conveying my fear of homelessness. I started my wedding post by talking about how I once thought weddings were the dumbest thing ever.

You want the reader to feel the poignancy of the problem as if it were his own. Sometimes you may not even indicate the problem until you’re 30% of the way through your post. That’s fine. Remember, you’re telling a story, not a message.

Brevity isn’t the primary goal. Connectivity is.

I was roughly 1,500 words into the travel post when I finally discussed the central problem. But that’s what it took for me to make the reader feel as if he was the main character himself. This is far more powerful than simply recounting the issue I wanted to address.

Allow the reader to descend into that big problem with you. To understand what big challenges he will need to face as he makes his way through the post. Only then will he feel the power of the resulting solution as if he discovered it himself.

(B) Revealing the Takeaway

Great articles are like great movies. There’s always a fantastic reveal that happens somewhere in the final half that brings everything together. An “a-ha” moment that you can take with you.

However, the thing that makes a reveal so great isn’t the reveal itself, but everything that leads up to that point. So it’s time to zoom in on this part of the narrative arc and deconstruct it a bit:

A close friend once told me that a well-articulated problem is a problem half-solved. I love that. If you’re able to clearly communicate the problem at hand, you’ve already done most of the legwork in solving it.

This applies to good storytelling as well. The best way to work up to the reveal of a solution is to frame the problem in a multitude of ways. This type of multi-angle view will clearly convey the root of the problem, and then illuminate a solution in turn.

In the travel post, I did this by framing travel through various lenses, and showing that each lens still led to general discontent. For example, going on 2-week vacations won’t make us happy because we will have to face everyday reality shortly. But what if we extend this lens outward and do a long-term move instead? Well, that might feel exciting initially, but eventually the allure of a foreign environment will subside.

By experiencing the problem in different ways, the reader can viscerally understand that the answer must reside somewhere else. In this case, the solution was to focus inward, as a discontent mind travels with you wherever you go:

This steady move from the problem to the solution is the most important part of the Visceral Journey. It is here where the reader will feel the emotional resonance of the story the most, and understand the takeaway you wanted to convey.

To do it well, it’ll be good to brainstorm things a bit. Here are three tips that help guide the reader to the big reveal:

– Use some personal examples that clarify the takeaway.

If you’ve been using the second or third person throughout your piece, try going first person for a moment. Readers love it when they know if something worked for you personally, and that’s a powerful tool to use if you ever get stuck.

For example, in this post, I used a personal story about becoming a full-time musician to clarify why it’s rational to take big life leaps. This helped the reader understand that this is something I experienced myself, so there’s a point of reference that she can directly connect to.

– Use great quotes that illuminate the point.

Sometimes age-old wisdom can articulate some things far better than we ever could. Don’t overuse this, but inserting a poignant quote can make the takeaway quite concrete for the reader.

For example, I used this Socrates quote in the travel post:

That did a good job reminding the reader that this insight was a timeless one.

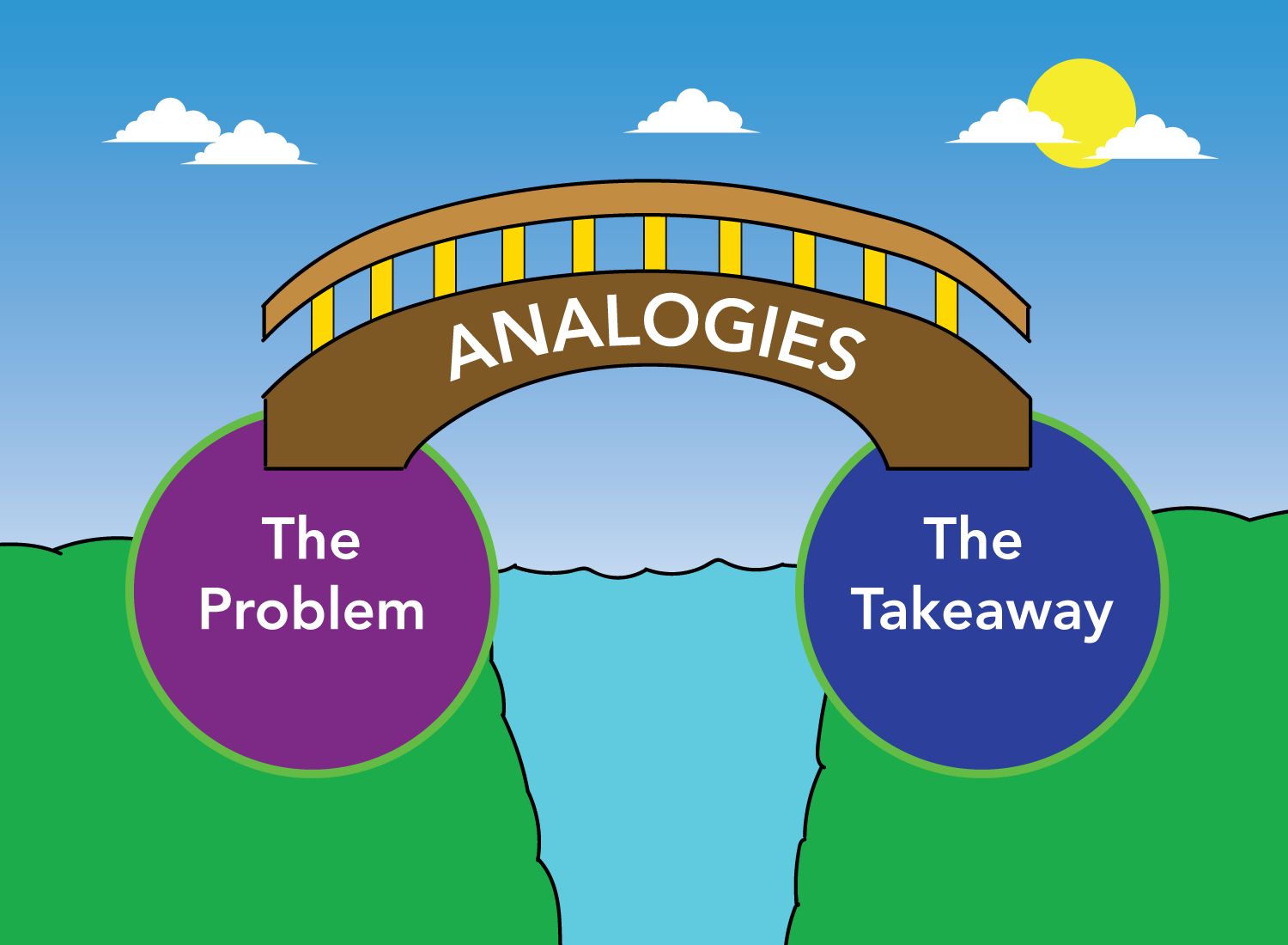

– Use analogies.

We’re going to go into this more when we discuss the visual component, but analogies are a great way to make concepts stick.

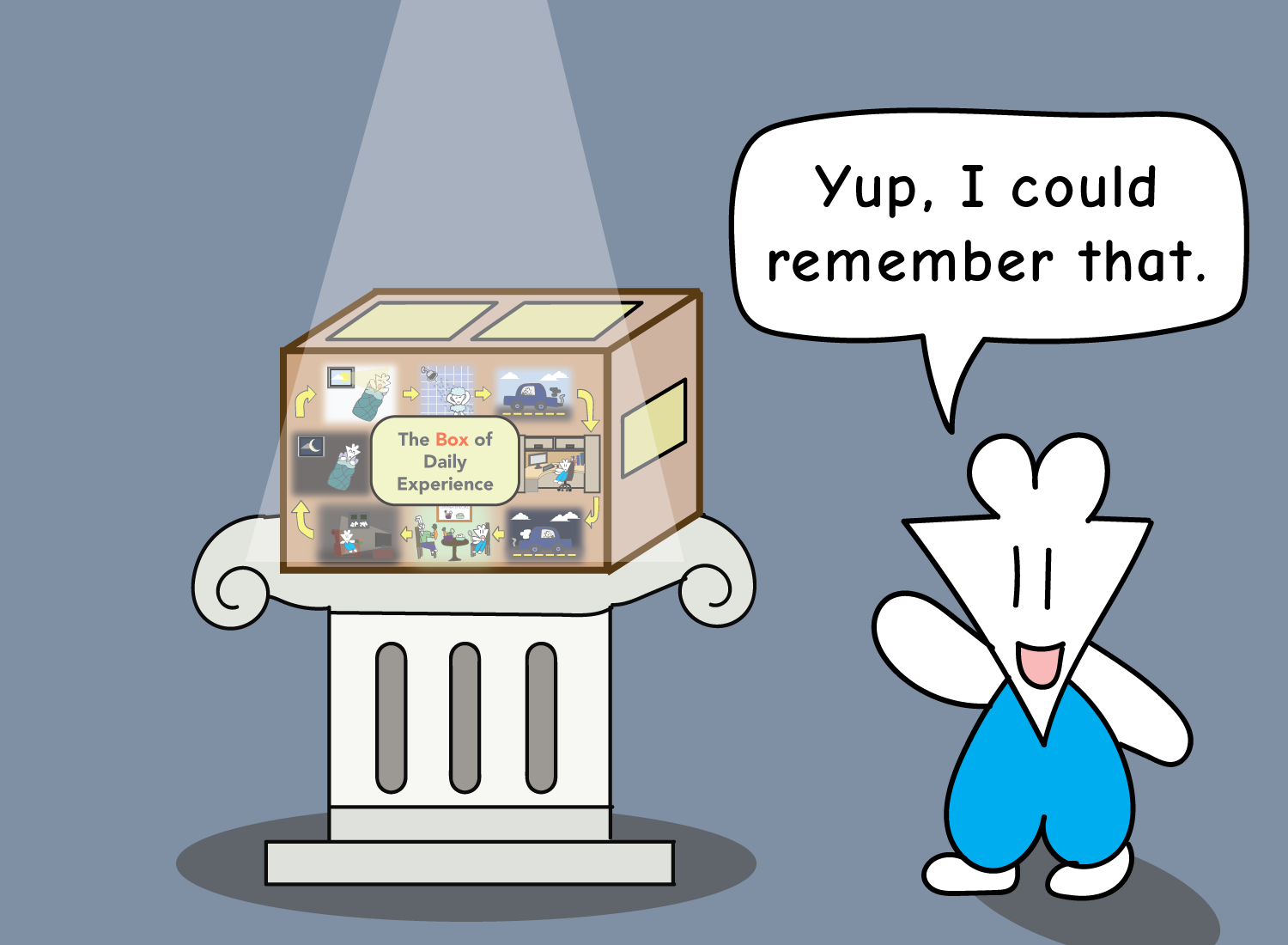

For example, by referring to everyday life as the “Box of Daily Experience,” I am creating an analogy that people can remember and interact with.

If you want to break out of the box, that means you’re trying to escape daily life. If you embrace the box, that’s another way of signifying gratitude.

These are simple ways to remember deeply layered concepts, and they go a long way in making the final takeaway stick.

Analogies are a great way to guide the reader toward the takeaway, but once you’re there, you need to give concrete examples of that solution at work. That way the reader will be able to take away something concrete and apply it to their lives.

Let’s briefly turn our attention to the final part of the arc:

This last part is when you drive the takeaway home. Provide an actionable framework of how the reader can apply it to their life.

These were the three examples I gave of the takeaway in action:

(1) Be grateful for your daily life so you don’t long for novel experiences,

(2) Go deeper into your existing friendships instead of wanting new ones,

(3) Travel into the minds of others by reading and interacting with their work.

By giving each example, I’m providing the reader something concrete to ground the takeaway in. Instead of simply saying “appreciate what you have now,” it’s far more powerful to highlight a few real-life cases where that insight is manifested. This will allow the reader to feel the poignancy of the takeaway as if they were experiencing it themselves.

This is the key to crafting a resonant Visceral Journey. Place yourself in the shoes of the reader, and have them go along with the path of discovery with you. Have them feel what you felt when you came to certain realizations yourself. Sometimes you’ll have to delay the delivery of your central point to do that, and that’s perfectly fine. After all, epiphanies take time to develop.

Much of good storytelling is about repeating this process over and over again. After crafting multiple Visceral Journeys, you’ll get a sense of what works and what doesn’t. Over time, you’ll develop a style that is unique to you.

Step #4: Simplify the message visually

Now that we’re equipped with some storytelling techniques, we’re finally ready to incorporate some visuals into the journey. As I said earlier in this post, visuals create an undeniable aesthetic, and they’re incredibly useful in conveying an idea.

But perhaps you’re not convinced that visuals are necessary for what you do. Or you think that your ideas are much better communicated in a format that is solely text-based.

I can’t argue with that sentiment, as your work has its own character and texture that is surely different from mine. All I can speak on is my own stuff, and if you’re curious about my thoughts on visuals as it pertains to More To That, then this section is for you.

To start, I want to give you the three main reasons why I’ve chosen to use illustrations for my work:

(1) Visuals give people a moment to digest what they read (especially if it’s non-fiction)

I write a lot about philosophy, psychology, and the general human condition. These are fascinating topics, but a lot of the content could be quite dense, especially if you’re trying to parse through source material from academic journals and verbose authors.

Oftentimes, you get paragraph after paragraph of jargon and 50-word sentences that feel like an onslaught of knowledge. Your mind has to be ready to process all this information throughout it, and it could be a relentless cognitive exercise at times.

Visuals provide breathing room for the mind. They break up large chunks of text into smaller building blocks, and provide the space required to bridge the gap between them. They allow the reader to briefly pause their cognitive intake, and use their imagination to play with the concept that is being conveyed.2

(2) Visuals are a great to way to simplify complexity

When someone is reading my work, I want them to feel a clarity of mind. Confusion may be fun to entertain, but too much of it will ultimately create distance between me and my audience.

However, complexity is often a prerequisite in the journey. Detailing the neuroscience of anxiety is not easy to walk through. Trying to explain our relationship with money is a complicated endeavor.

That’s just how it is for humanity’s deepest problems.

Fortunately, illustrations help alleviate this issue. Distilling lengthy processes into a single image helps ground the reader and makes the concept graspable. Anxiety can now be imagined as an interplay between three islands. Our relationship with money can be summarized as a spectrum with three main phases.

Illustrations help the reader by invoking the comfort of simplicity.

(3) Visuals create interesting characters that the reader can identify with

In fiction, it’s important for the reader to feel as if they are in the central character’s shoes. The best storytellers are able to blur the line between reader and author, and make the reader feel like they’re a seamless part of the narrative.

With non-fiction, that’s harder to do. The reader is going into your work knowing that they’re here to read your thoughts. There’s no suspension of disbelief, no other character’s mind they are looking to occupy.

I love illustrations because they allow me to blur the lines here. By introducing a cartoon character in my work, that creates a new entity that the reader can point to as the central character for that story. Yes, they know that I’m the narrator, but now they’re following the arc of this character as opposed to my own personal experiences.

This gives me the freedom to create stories that may not be specific to me, but can embody human experience as a whole. My recurring characters are a cast of personalities that help frame various emotions. Some are rational, some are impulsive, and some just have no idea how humanity works.

By using them as central characters for my posts, I create different vantage points that the reader can relate to with each story. It’s no longer about me as the sole author; there’s another “being” there to guide the narrative along.

Ultimately, visuals allow you to condense narratives in a digestible, simple, and memorable way. This adds a stickiness to your ideas that are difficult for large blocks of text to do.

Now that I’ve shared why I use visuals, let’s now go through some techniques to indicate how we could maximize them.

My favorite technique is to visualize analogies that bridge the gap between the Problem and the Takeaway:

If the analogy is great, the reader will remember how that visual helped them resolve the conflict that the Visceral Journey addressed.

As I mentioned earlier, I used a cardboard box in my travel post as a visual analogy to convey the events of daily life. I’ve used many analogies throughout my work: weights to symbolize problems, lights to act as memories, trophies to represent writing, the list goes on.

Not only do analogies stick with the reader, they also help you think through issues clearly as a creator well. When you think in analogies, you are condensing your ideas to their simplest form. This enhances your ability to communicate them better, which will make your story that much more compelling in turn.

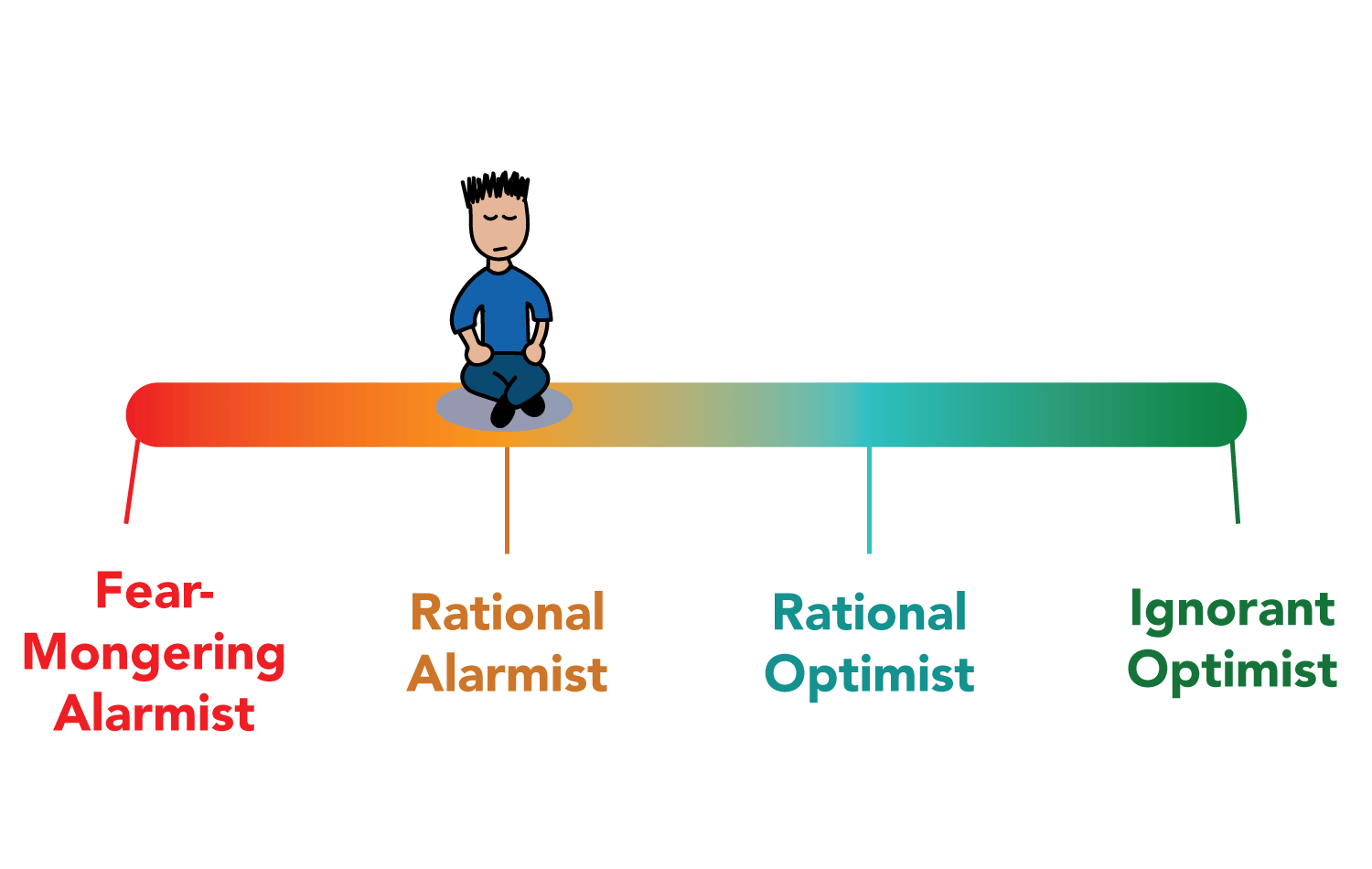

Another way to condense the narrative is to use diagrams.

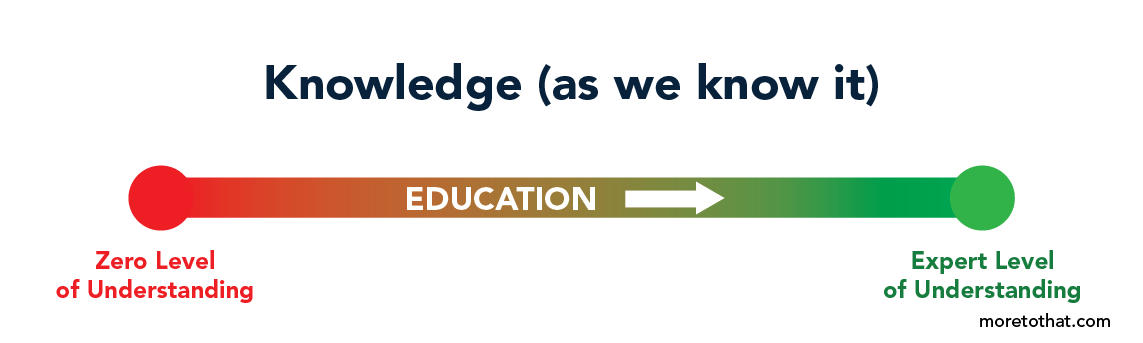

Spectrums are great if you want to convey the gradient of things that exist between two poles:

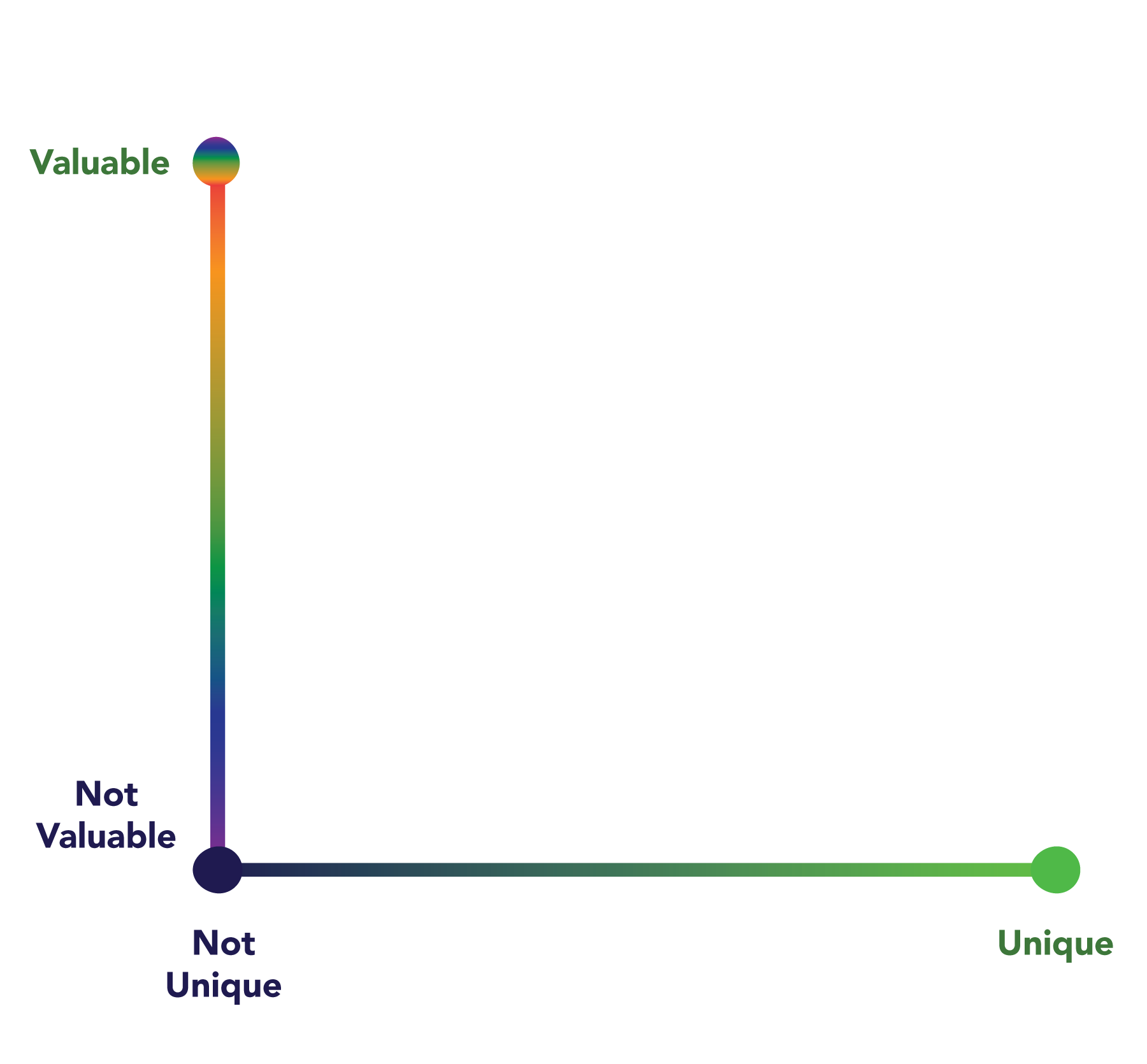

Two-axis graphs are fantastic if you want to illustrate a concept as a blend of two independent variables:

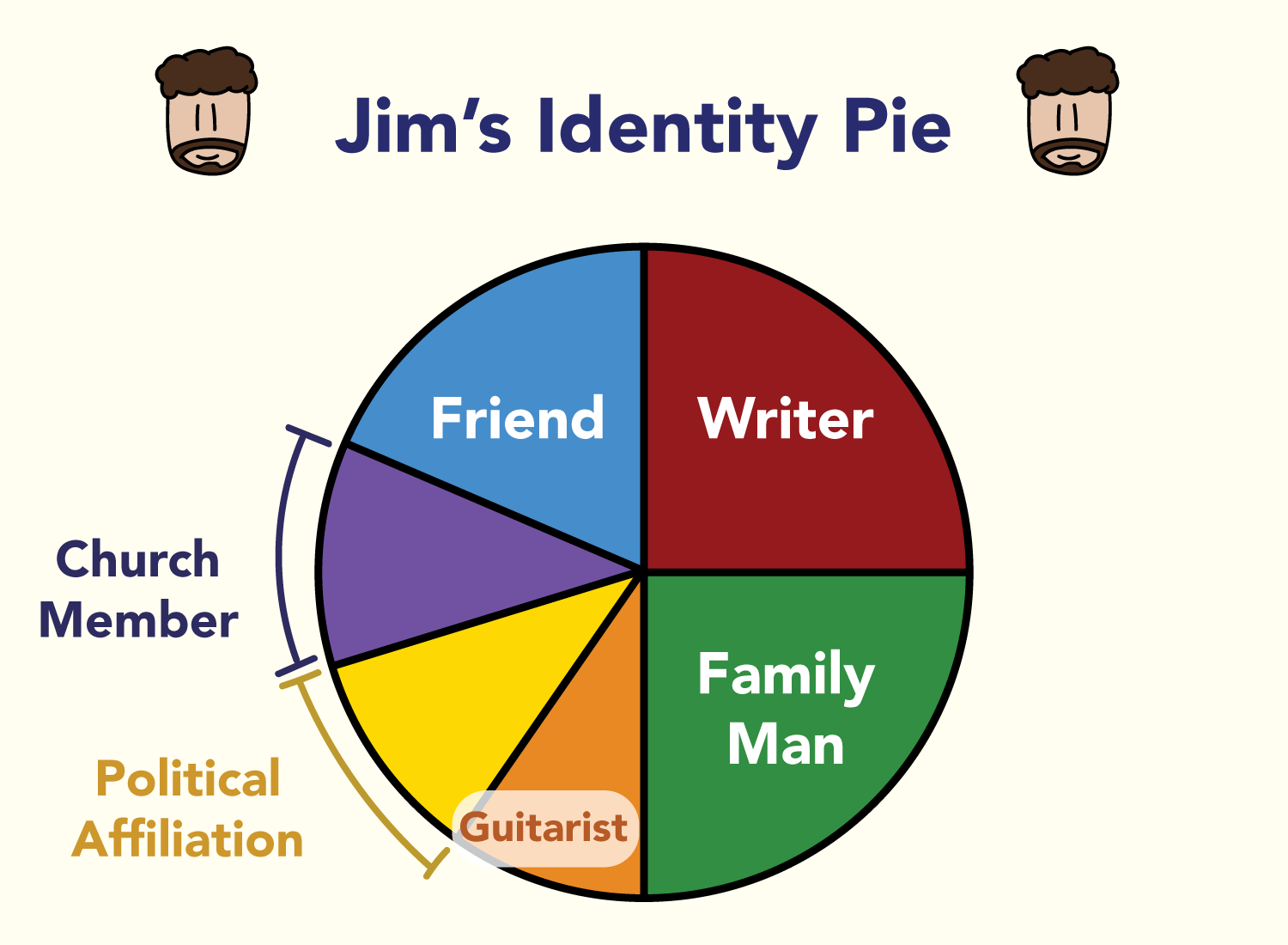

And I’ve even used pie charts to signify the different parts of one’s identity:

Diagrams are great because they convey so many words in a single image. They are great visual aids to your story, allowing the reader to digest everything you just communicated over in words. It also acts as a sticky image that you can point to for future reference.

So when exactly should you use a analogy, diagram, or any other visual? Well, the best answer is to let your intuitions guide you. Ask yourself some of these questions as you’re writing. If the answer to any one of them is “Yes,” then it’s a good time to try out a visual cue:

- Does it sound like I’m rambling at this point?

- If I were to add another paragraph to explain this concept, would it just make it more confusing?

- Does my story seem a bit boring and stale?

- Is there an amusing reference I can make here that would make this point more relevant?

When you feel that little tug of creative inspiration to try something else, it could be a good time to see how a visual would work. It will introduce something new for the reader, and also for your own process as a creator.

And lastly, perhaps my favorite usage of illustrations has to do with simply moving the story along. Most of my drawings aren’t analogies or diagrams; they are simply visual aids that bring a story to life.

If you look at my opening story to this post, none of those drawings were about simplifying some complex concept. They were simply visual aids that introduced a comedic element to my childhood story and gave it some character.

I believe that everyone has an inner child, no matter how old they are. Even if you’re 80, there’s something about cartoons and illustrations that bring a bit of joy to existence.

Perhaps the biggest reason why I use illustrations is about providing that little spark of delight for my readers. Even if it takes me hours and hours of work to do, knowing that they enjoy the drawings for a few minutes makes the whole endeavor worth it.

Once you connect with your audience in that way, it’s only inevitable that creating delight becomes second nature.

The Era of Visual Storytelling Is Here

Everyday we are presented with content from all over the globe. Some of it is created by faceless corporations with multimillion dollar budgets, while most is built by ordinary people with a computer and an internet connection. That’s where my work falls under, and yours probably does as well.

This is both daunting and hopeful. Daunting because you know that you’re just one small node among a sea of creators, trying your best to spread your message across the world. Hopeful because you understand that your audience is already out there; you just need to put in the work to reach them.

Visual storytelling accelerates your ability to reach this audience. The combination of a compelling story with a recognizable aesthetic is a magnetizing force that is hard to ignore. With each Visceral Journey you create, you are sending up a beacon of light, telling people that there’s a new ride in town that you’ve built with much effort.

And speaking of effort, that’s what visual storytelling ultimately conveys to the reader. If you’ve gone through each of the four steps I’ve outlined, that effort will most definitely show in your work.

It’s quite easy to tell if something took a few minutes to do, or if it took a few days. It’s even more easy to recognize what took a few weeks or a few months.

The thing about creating on the internet is that most people don’t invest much time in what they make. Since it’s so easy to write something and hit publish, it’s far too enticing to make use of an instant distribution channel that was once unthinkable. As a result, we get a ton of content, but very little substance.

This is the greatest opportunity for a visual storyteller. If you take the time to build thoughtful journeys that viscerally connect with others, they will stand out in a way that not much else can. There is a hunger for stories that require deep reflection to put together, and you are in a great position to fill it.

It might take a long time to put a journey together, but remember this:

What takes weeks for you to build will last for years to come.

A wonderful narrative will continue to attract people well after you’ve released it. Your stories will take on a life of their own as they are shared by the people that love them most. They will become beacons that represent you, whether you’re physically present or not.

Stories are the artifacts of humanity that outlast the material self. They are the invisible force that keeps us connected, and each one has its place in this ever-evolving project we call humanity.

Don’t miss your chance to contribute to this endeavor. Tell your story.

You have no idea how impactful it could be.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

If life were to follow a video game narrative, this is what it’d look like:

Here’s my biography of an incredible man’s existence:

Socrates: The Badass Godfather of Uncertainty

For my take on the greatest story ever told: