Thought Stop Signs: The Source of Lazy Thinking

Philosopher George Berkeley had a big problem to solve.

He was developing his controversial idea that the universe was made of a single substance, which he believed to be thought. He said that all knowledge came solely from personal experience, and the only thing that determined an object’s existence is if we perceive it to exist. In other words, it wasn’t physical matter that built the universe – it was mind.

So if it looks and feels like you’re holding your phone, then your phone actually exists. If you look out your window and see that the sky is blue, then the sky certainly is blue. And if you happen to see that one shirtless guy in your neighborhood power walking again, then sadly, him and his loose chest hairs do indeed exist.

Berkeley summed up his position with the Latin phrase esse est percipi, which means “to be is to be perceived.”

At this point, Berkeley was quite happy with himself as he feather dusted his shoulders off in pride. It all made perfect sense to him. Thoughts and ideas are what govern the universe, so the material world exists only because our minds are there to perceive it. Without mind, there is no matter to perceive, so the existence of anything hinges upon our thoughts and ideas.

It’s easy to see the problems with Berkeley’s conclusion today, primarily because we’re well aware of how the mind isn’t as reliable as we’d like it to be. Our awareness of cognitive biases, mental models, and all that goodness reminds us that our perceptions are poor constructors of reality, and that we need to question our senses to arrive at the truth.

But even in Berkeley’s time, there was a popular rebuttal that threatened the validity of his view. In fact, if he didn’t get this right, then it’s quite possible that his whole argument would collapse.

The rebuttal was simple: If objects in the material world exist only if they are perceived, what happens when the perceiver is no longer present? Do all the objects then cease to exist?

For example, if I leave my room now and go for a walk, what happens to my desk, my computer, and this cup of water I’ve been sipping on? Do they disappear because I am no longer perceiving them, and then reappear once I return? That sounds like a reality that eludes any rational framework.

After some intense reflecting and philosophizing, Berkeley decided that he had a great response:

When I walk out of my room, the room and its contents continue to exist, because there is still a perceiver watching over it all.

And who might this omnipresent perceiver be?

You guessed it.

The big G-O-D.

So according to Berkeley, if a tree fell in a forest but no one was there to observe it, it did fall because God watched it fall. God’s active role in the world allows everything to be perceived at all times, whether any human is present or not.

I find it interesting that Berkeley, one of the great philosophers of the early modern era, came up with this rather elusive response. Not because I scoff at the idea of God or Berkeley’s religious affiliations, but because his retort feels like an intellectual dodge.1

Instead of dissecting the rebuttal and running it through various scenarios, Berkeley decided to press the thinking brakes and evoke God as his answer. By doing this, he’s making a statement that you can’t further falsify, because doing so would mean that you’d then have to argue about whether or not God exists. That’s a route that you don’t really want to go down, so by responding with “God,” Berkeley is effectively stopping the discussion from going any further.

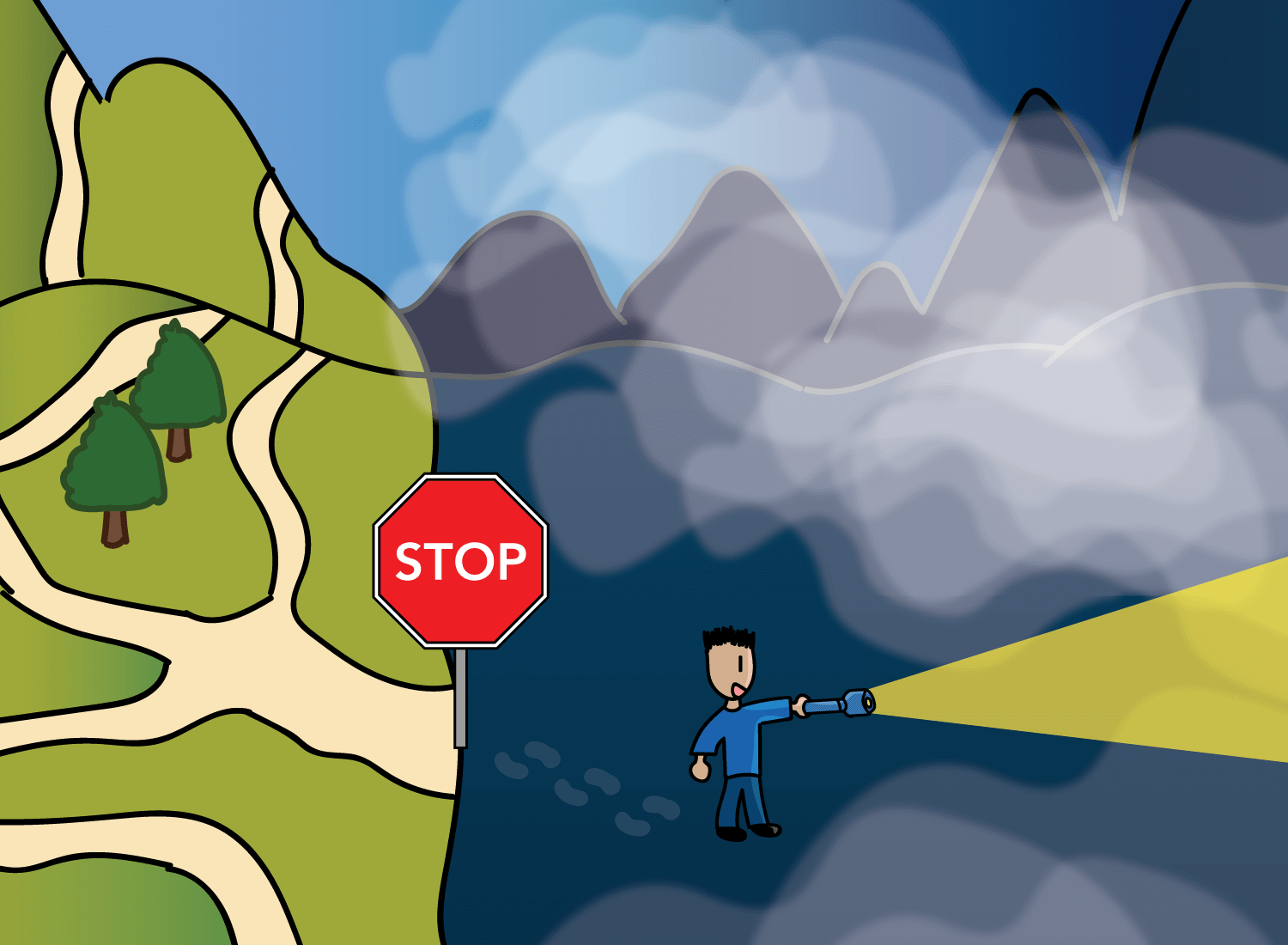

I call this a Thought Stop Sign, which is a word or phrase that is intended to put an end to an otherwise sound line of reasoning. Before this stop sign is present, people are willing to explore and go deep into the thought trenches, navigating all the winding paths necessary to expand upon their positions. This allows for open-minded discussions where claims are falsifiable, which is a prerequisite in any rigorous search for truth.2

But the moment a Thought Stop Sign appears, the territory beyond it goes dark, clouded by the fog of misplaced certainty. The sign indicates that past this point, we will no longer be exploratory in our thinking, but will instead resign ourselves to our deeply-held and unmovable beliefs.

This reminds me of the scene in The Lion King where Mufasa sits with Simba atop a beautiful hill, surveying the landscape of their entire kingdom. Mufasa tells his son that any territory the sunlight touches is free to roam, but he must never enter the areas where the land is covered in darkness.

This analogy can be imported into the intellectual landscape as well. On one side, you have the sunlit territory of free-roaming thought, and on the other, the dark territory where any inquisitive thinking must cease.

In between these two areas sits a big, red Thought Stop Sign.

In Berkeley’s case, his usage of “God” as his stop sign isn’t all that surprising, given that he was an Anglican priest (and later, a bishop). But even if one has no religious inclinations, we all have our own Thought Stop Signs, and each of them carry the same kind of resonance that a word like “God” would have.

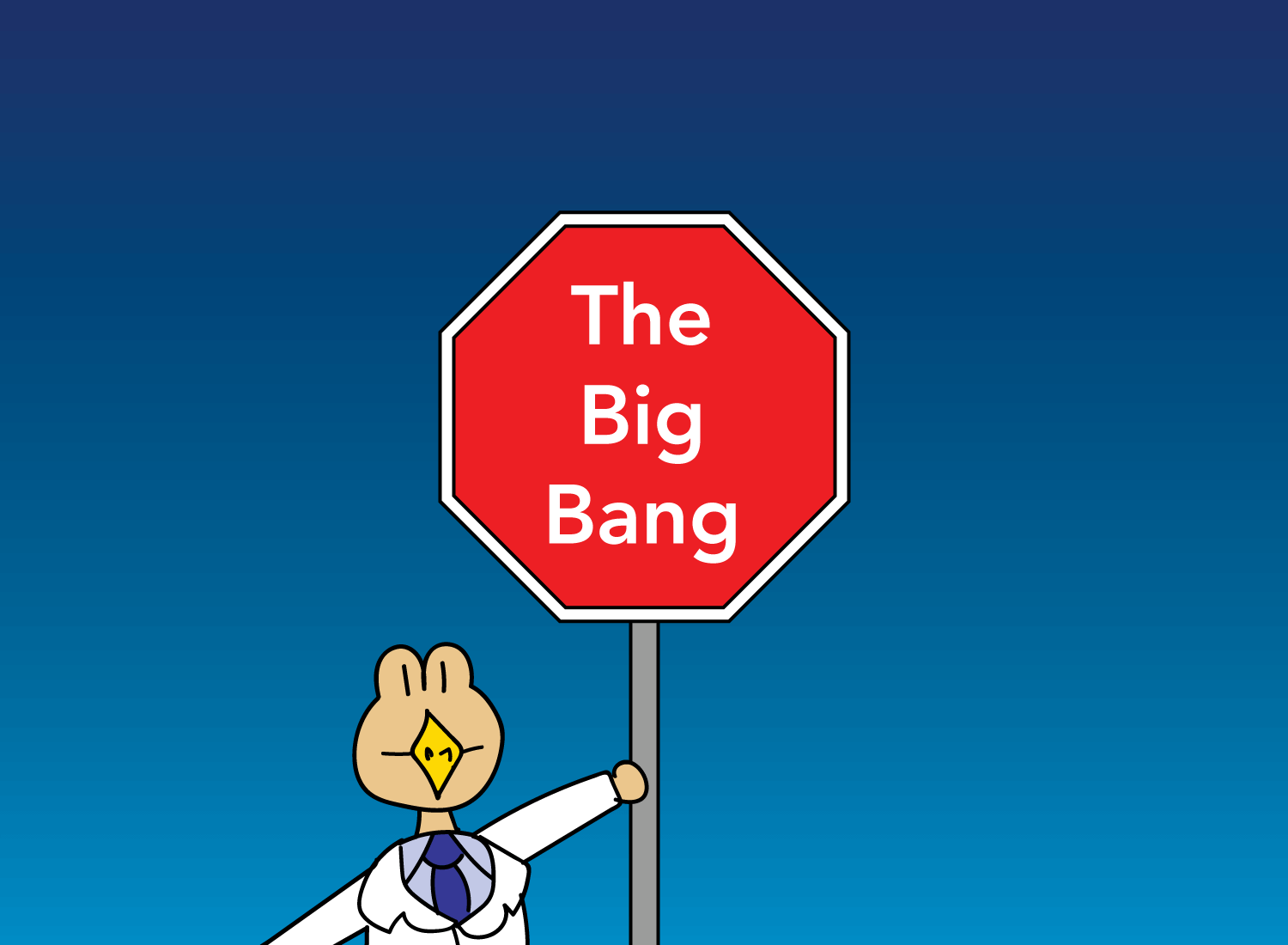

For example, take the question of how the universe started. One can take a strictly rationalist and materialist view of the cosmos, determine probabilities, construct theorems, and build intricate models. But all this exploratory thinking eventually culminates in a conundrum that no one has yet to solve:

How the hell did something arise from nothing?

And with this question, we arrive at this beloved Thought Stop Sign, which essentially is another way of saying “God”:

A general feature of a Thought Stop Sign is that it is accepted as a reasonable explanation to the in-group, and rejected as an absurd excuse to the out-group. Creationists will say that God handcrafted the universe, and will scowl in disbelief at anyone who says the universe started with a bang. Physicists will say the same, but in reverse.

The irony is that both groups have no real idea of how something came from nothing, but they’ve taken their respective stop signs to be gospel. When a Thought Stop Sign becomes the consensus response to a difficult question, it begins to feel like it’s actually a well-thought out conclusion. This makes you double down on your certainty, providing a false sense of confidence that your answer must be the right one.

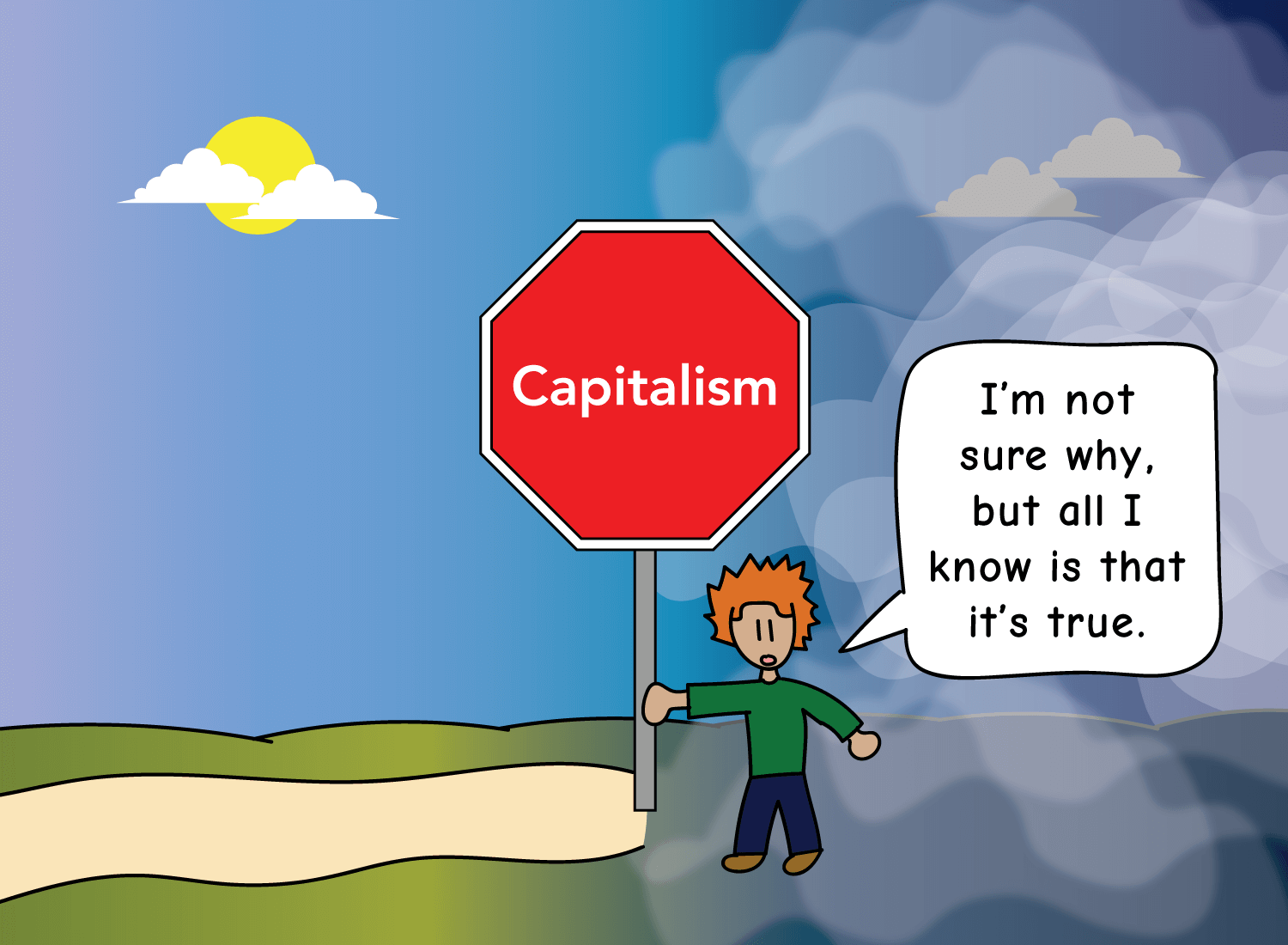

I see this quite often in economics, where the system that the individual is a part of is what is heralded as the superior way. For example, many people living in affluent cities in the U.S. will sing the praises of capitalism, and how it’s inherent in the nature of our species. To hear anyone counter this with an argument for socialism would be akin to hearing that the Sun revolves around the Earth. They would feel the same kind of bewilderment, even without having a firm grasp of the argument at hand. After all, most people that have “capitalism” tattooed across their brains have never read a word of Adam Smith in their lives.

On the flip side of this are people that believe “all corporations are evil.” No matter how ethically sound a company and its constituents may be, the mere fact that it’s a corporation makes it worthy of criticism. People here generally have never built a company themselves, but naturally, it’s easy to be critical of something you don’t know much about. Gaps in personal experience tend to be filled with cynicism, and this often leads to Thought Stop Signs that are solidified by false confidence and spite.

As I write this, I’m reminded of the gaps in my own thinking, and the Thought Stop Signs I have as well.

One is my belief that democracy is the best political system available to us. Or as Winston Churchill more accurately put it, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” I’ve bought into democratic values, despite having no firsthand knowledge of what it’s like to live in an aristocracy, military dictatorship, or monarchy. The lessons of history are acting as my guide here, although I’m likely filtering those lessons through a lens that is skewed toward my deeply-held belief.

If someone were to argue with me about why a dictatorship is a better form of government, I may listen intently, but nothing they say would likely change my mind. That’s how I know “democracy” is a Thought Stop Sign for me. I will engage in a chain of reasoning because it’s interesting to do so, but the outcome has already been determined before the discussion has even begun.

Upon recognizing this Thought Stop Sign, the next question I must ask myself is, “Okay, so what do I do now?” If I choose to merely accept its presence, I’ve admitted that I’m okay with being a lazy thinker, which in my line of work is an occupational hazard. I certainly don’t want that, so the next step is to understand how I could move past it.

The initial place to start is to understand why it’s there in the first place. And when it comes to a Thought Stop Sign’s existence, it boils down to one of three reasons:

(1) You’ve personally benefited from having the belief,

(2) It happens to coincide with your identity,

(3) You’re fearful to admit otherwise.

#1 is the most common reason why “God” or “democracy” or “capitalism” are popular stop signs. God feels comforting, democracy feels fair, and capitalism feels lucrative if you have experienced the benefits from living within these models. Even if there are millions of people living good lives that don’t subscribe to any of these words, your attachment to personal experience will make you feel like these are the best systems and values for all of humanity to incorporate.

#2 occurs when new ideas you come into contact with happen to align with your cemented worldview. This makes you quick to accept that idea based on the mere association it has with your identity. For example, this is how something like wearing a mask has become a political issue. Even though the biological implications of mask-wearing have no logical tie to any political party, the fact that influential politicians adopted different stances turned it into a Thought Stop Sign.

#3 is when the holder of a stop sign actually wants to remove it, but is scared of what his tribe may think if he does so. This is the person that secretly votes for the candidate that his friends aren’t voting for. The person that has lost her faith, but continues to go to church to show face. People in this bucket have done all the intellectual work of developing their position, but just need a push of courage to take them to the other side.

When you look at your own stop signs, which of these three reasons explain the reason for their existence?

For my “democracy” example, it may seem like Reason #1 is the clear culprit, but it may actually be a mix of all three. My personal experience with living in a democracy is likely making me close-minded to everything else (Reason #1). My identity as an American citizen certainly doesn’t help (Reason #2). And advocating for a new system of government might alienate me from the millions of people that take pride in this nation’s foundations (Reason #3).

Whatever reason it is, the only way to lessen the power of a Thought Stop Sign is to actively introduce uncertainty again. This may seem counterintuitive, given that we learn to grow our knowledge and become more certain about how reality works. However, the presence of a Thought Stop Sign is a clear indicator that your certainty is now unfalsifiable, which means that your rate of learning will essentially grind to a halt.

By introducing uncertainty back into the equation, you decide to observe the belief without any preconceived notions, and without the biases of personal experience. You are making the concerted effort to move past the stop sign, and to be exploratory in your thinking once again. There’s no guarantee that you can do this with complete objectivity, but the mere attempt is what matters.

There are some practical ways to do this, and one thing I like to do with my stop signs is to proactively find sound arguments against them. Thankfully, the internet is a godsend when it comes to finding a diversity of thoughts and opinions, so all I do is a Google search for “arguments against (insert view).” You will find a ton of articles, videos, and Wikipedia entries that construct a rather thorough view of the other side, and will give you a good sense of what you’ve been missing this whole time.3

One thing you’ll realize when you do this regularly is how reasonable the other side may sound. As you read through the various opinions, it’ll become clear that there’s a lot you’ve missed by sheer ignorance, and there’s a lot you’ve dismissed as absurd without learning the best possible interpretation. Thought Stop Signs give permission for lazy thinking, so it’s common to take the least informed argument and assume that to be the entirety of the other side.

To combat this, it’s important to frame the opposing side’s argument in a manner that they would agree with. Give it the most charitable interpretation, and use that as the basis for making your point.

For example, if I was arguing with someone about why democracies are superior to dictatorships, it would be naive of me to use Hitler as my go-to justification. That’s me giving the other side its least charitable interpretation. Rather, I should try to argue my position against someone like Lee Kuan Yew, the “benevolent dictator” of Singapore that ushered in an age of unbelievable prosperity for its citizens. If I could make the case for democracy even against someone like Lee, then I know I’ve done the intellectual work to move a bit beyond my Thought Stop Sign.

The problem is that this takes work, and most of us don’t want to invest the time and energy necessary to develop a well-rounded opinion in this way. That’s understandable, but if this is the case, be honest with yourself about it. Instead of pretending that you have the best picture of all sides, admit that you’re not presenting the sides equally. Be aware that you’ve cut off your chain of reasoning at the Thought Stop Sign, and that you’re not looking to go any further.

After all, the intellectual landscape is destined to have both bright fields of curious exploration and dark patches of stubborn certainty. This is because our time and energy are limited, so we have to choose our rabbit holes wisely. But for the pursuits that we’ve chosen to invest ourselves into, it would be a disservice to our intellect to stop thinking once we hit a deeply-held belief.

Eliezer Yudkowsky once wrote that “there are many more ways to worship something than lighting candles around an altar.” Taking inventory of your Thought Stop Signs is the best way to see which ideas you worship, as they indicate where you’ve halted your search for truth. But of course, the truth has no logical endpoint. It always forks into a separate road, which swerves into another, which branches off once again, and so on.

This is why we must continue pursuing the questions instead of being satisfied with the answers. By removing our Thought Stop Signs, we acknowledge this truth, and continue our march onward into the depths of the unknown.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Here’s an in-depth framework you can use to move past your stop signs:

From Ignorance to Wisdom: A Framework for Knowledge

Information paves the way for your perceptions, so use it wisely:

The Information Lifecycle: How Three Filters Shape the Mind

A short comic to guide you along your journey through reality: