The Three Types of Writing

A great tragedy of the education system is its inability to make writing an appealing skill. In fact, it feels like the system has been intentionally set up to make writing an absolute slog, which stunts intellectual growth and directs students to the path of conformity.

Consider the 5-paragraph essay for example.

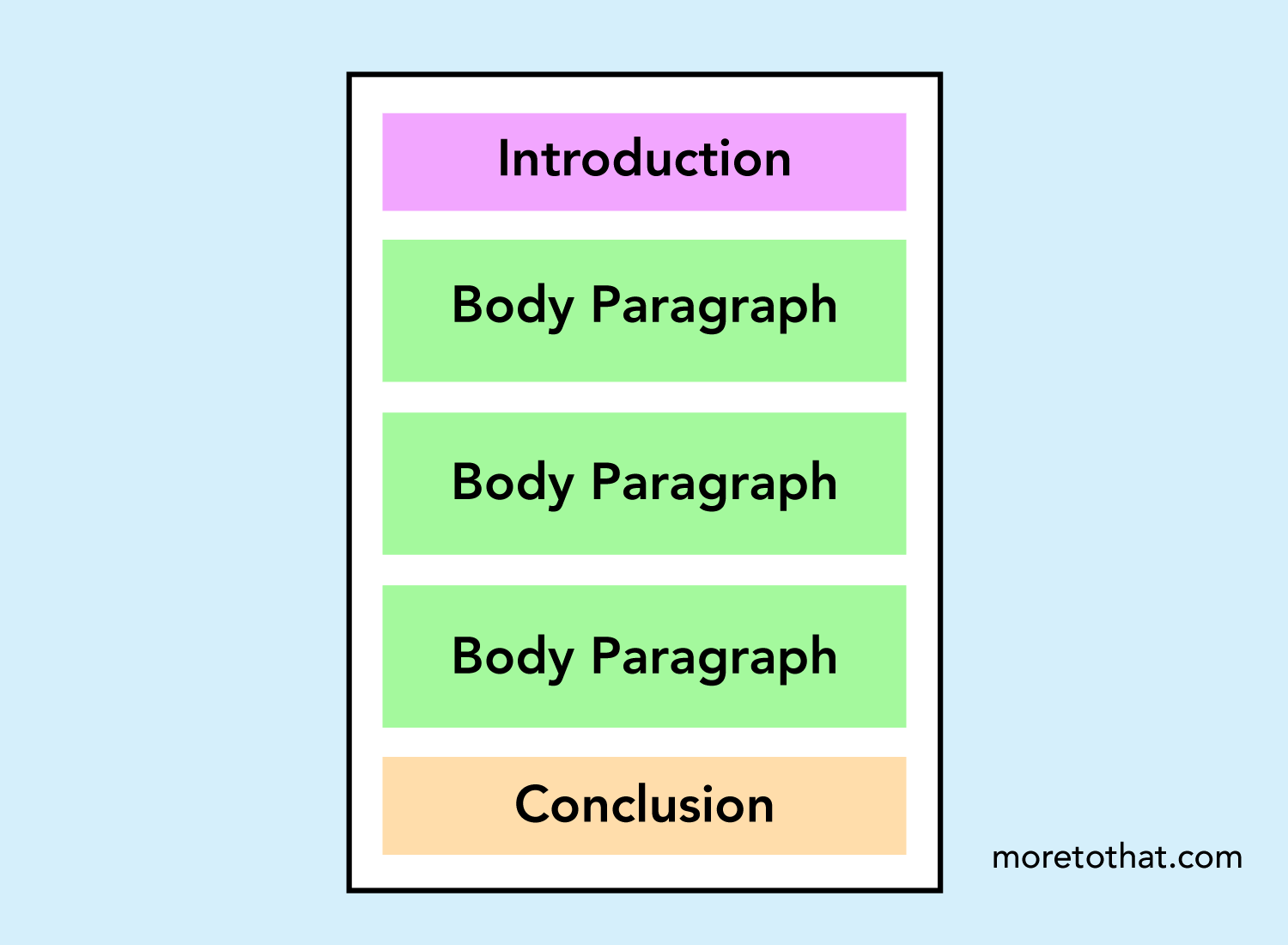

For those of you unfamiliar with this concept, this was (and still is) widely taught in high school, where you are told to structure an argument in 5 distinct paragraphs that look something like this:

You state your argument in the opening paragraph, provide supporting points in the subsequent 3 paragraphs, and conclude by re-iterating your argument. If you follow this structure well, then you’ll get an A and are told that you’re a wonderful writer.

First off, I don’t know a single person who felt called to writing as a result of learning this concept. If anything, I saw the opposite. People who enjoyed writing in their spare time because disillusioned with the practice after being taught that there was a standard way to do it.

Second, who actually enjoys reading this kind of essay? Your English teacher may feign interest because her salary depends on it, but no one in their right mind would place a 5-paragraph essay amongst their Mount Rushmore of literary works. No matter how great of a writer you are, the fact that you’re structuring your thoughts into a preset mold nullifies any potential toward greatness.

And yet, this is what we are taught.

After years of this, it’s no surprise that people exit the educational system with a deep distaste for writing. Its purpose seems to be an obstacle you have to overcome to graduate, and once you do, you can finally be done with it. You can move onto the things you enjoy, which have nothing to do with jotting your thoughts down on a page…

What you’ll quickly realize, however, is that this isn’t how it works. That’s because a functional adult life orbits around writing.

You want that job? You better know how to write a great resume and a cover letter.

You want that date? You better know how to write messages that don’t make you seem like a fool.

You want to get promoted? You better know how to communicate with your team through compelling emails.

You want to build an audience? You better know how to convey your thoughts through a blog, newsletter, social media, book, or a YouTube script.

You want to sell your services or products? You better know how to communicate the value you’re providing by writing out what it is.

The list of things requiring the skill of writing is endless. The problem, however, is that we’ve been conditioned to believe that writing is this boring, academically rigid thing that only applies in a classroom setting.

The liberating truth is that it pervades everything we do, so it’s worth reframing it so you can harness it. The daunting truth, however, is to know where to begin.

Consider this post a primer in re-thinking the craft of writing. As it turns out, there are 3 ways to use writing as a guiding practice for the direction of your whole life. That may sound grandiose, but once we get into it, you’ll see why I have confidence in saying this.

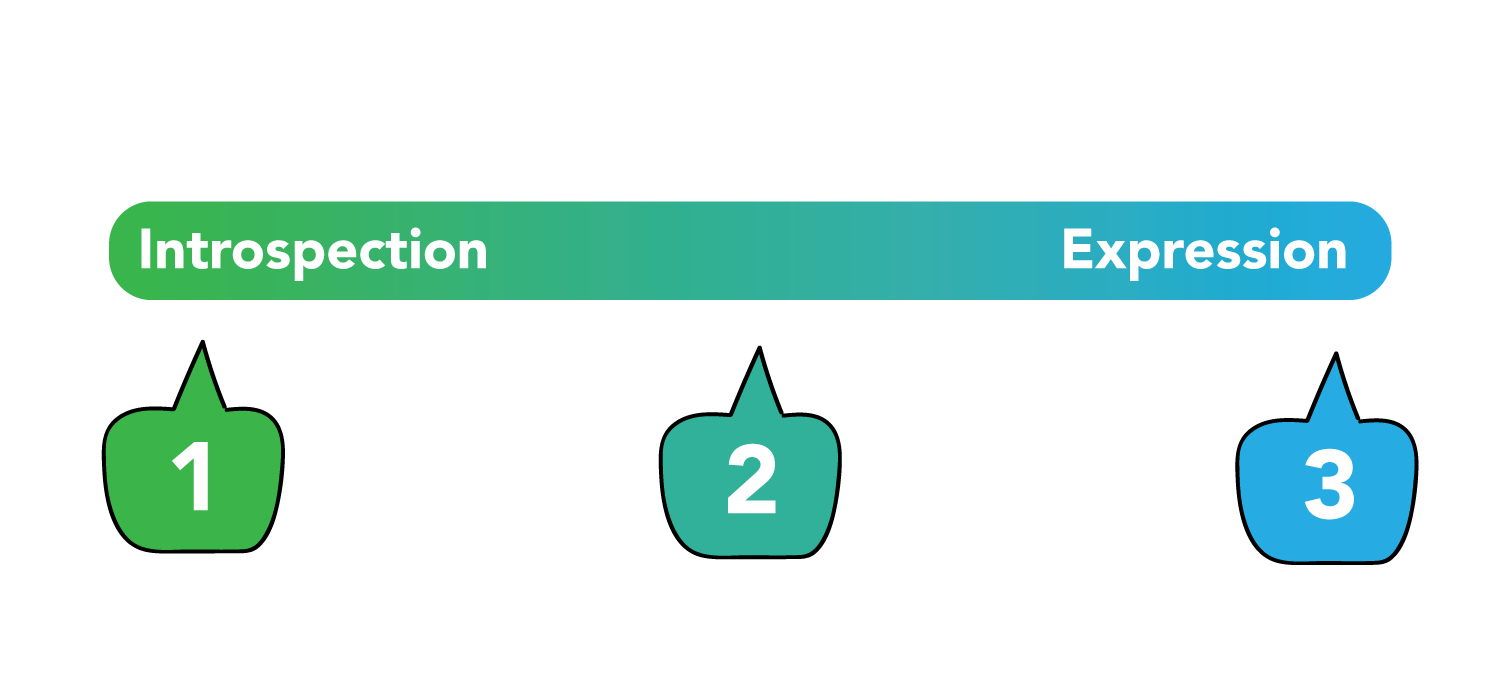

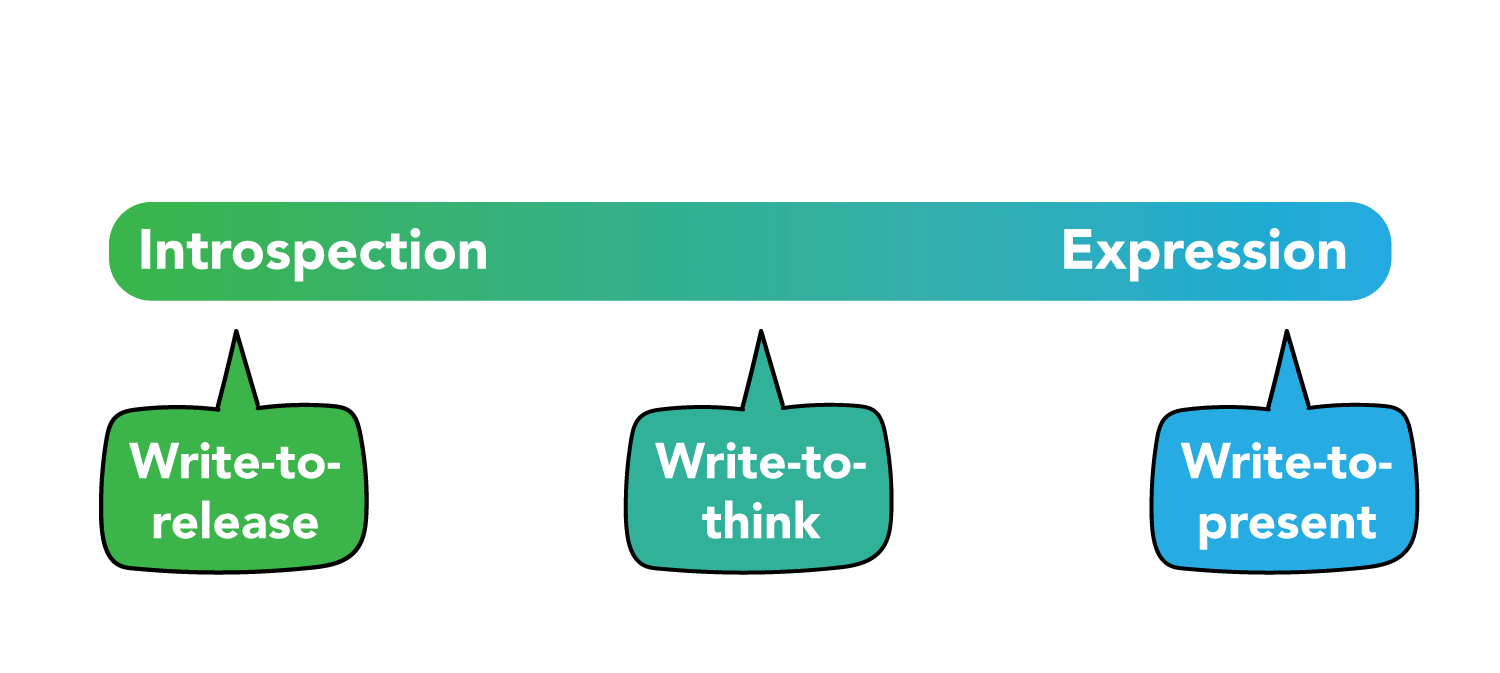

Let’s start with the claim that a well-lived life oscillates between two ends of a spectrum:

Introspection is about thinking through the course of your life and reflecting on how it’s going. It’s to find ways to calibrate your inner compass and to gain clarity into how you’re feeling. Simply put, it’s an exploration of your inner world.

Expression is about communicating and conveying your ideas to others. There’s a communal aspect to it, whether you’re trying to find your tribe or you’re looking to help others that you believe you can help. Simply put, it’s a connection with the outer world.

It’s a spectrum because life isn’t about one or the other. Periods of contemplation are followed by periods of activity, and there is a cyclical nature of sorts. But both are required to feel that your life has purpose and meaning.

Writing is what will deepen your involvement in both worlds, and will help to bridge the two as well. That’s because the three types of writing can be mapped out across the spectrum quite nicely, like so:

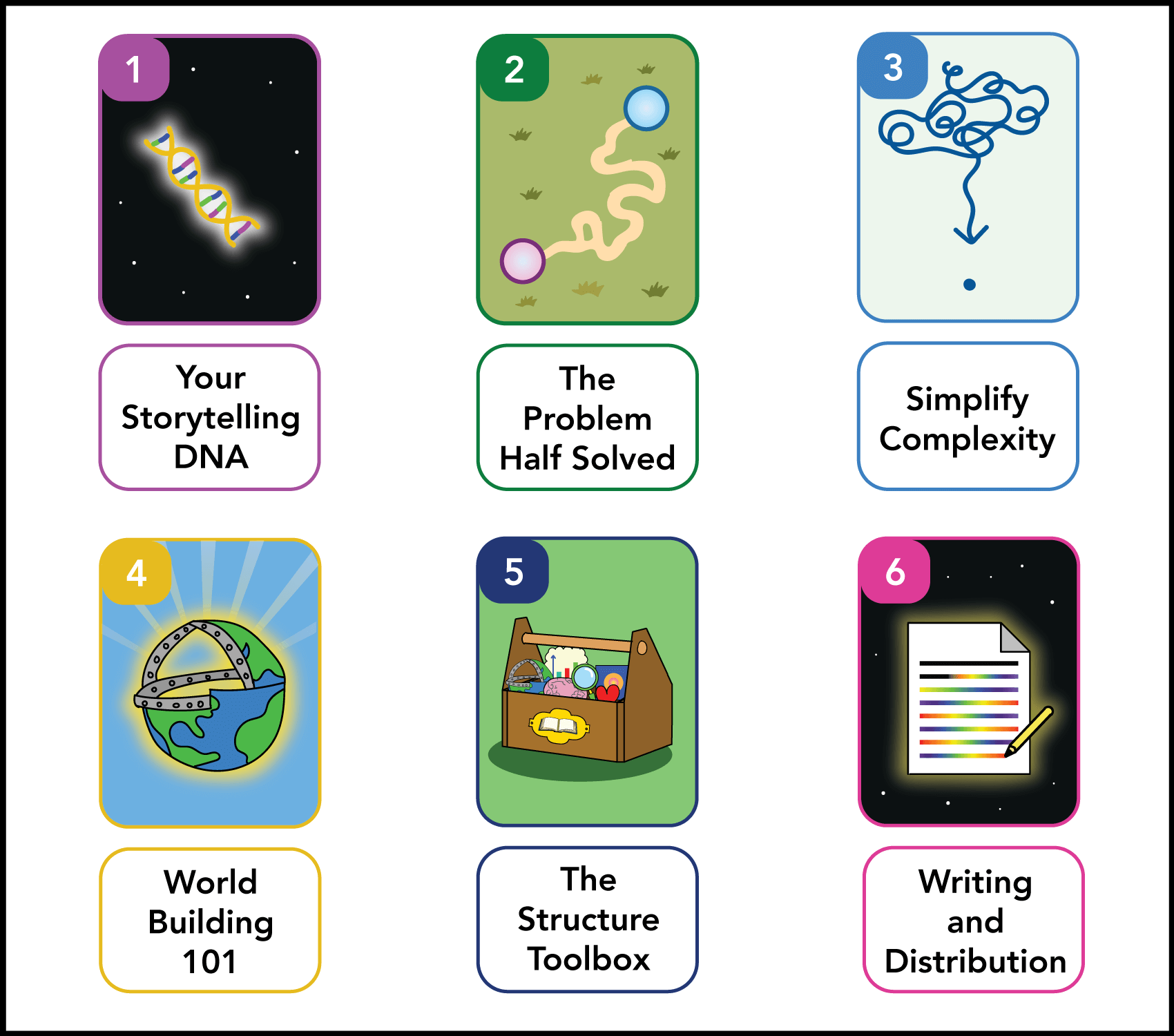

So what are the types of writing hiding between each of those numbers? Well, they are as follows:

- Write-to-release

- Write-to-think

- Write-to-present.

We’re going to touch upon each of them, and I’ll also provide some practical ways you could incorporate them into your own practice.

Let’s start from the top.

1. Write-to-release

In The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron popularized the idea of Morning Pages, where you write 3 full-length pages of whatever comes to mind. The key is to do it without judgment knowing that no one will be reading these pages but you. The only rule is that there is no rule to what your words will be about.

Feeling a bit anxious? Make a note of it. Got something you need to do later in the day? Write about that. Do the clouds outside look a bit funny? That’s fair game too. Nothing worthwhile to comment on? Write that down as well.

At first glance, you might wonder what the point of this exercise is. There doesn’t seem to be any obvious utility to it, given that the output can seem like the thoughts of a rambling madman.

The utility becomes more apparent, however, when you view this as an exercise in introspection. In other words, the output of the exercise isn’t what matters. It’s the fact that you did it that does.

This is a form of writing-to-release, where you dump out the contents of your unconsciousness onto the page. You use writing as an outlet to process the emotional and experiential artifacts that live within you, as simply thinking about them don’t give you the access you need. There has to some form of action that draws those artifacts out, and a reliable way to do this is through the avenue of writing.

It’s important to note that style, grammar, and syntax hold no regard here. You can jump off on a tangent mid-sentence, make liberal use of ellipses when periods will do just fine, or mix together words that don’t feel like they belong. All the rules you’ve learned about writing can be thrown out the window because the only thing that matters is your ability to capture your thoughts and emotions, which by nature, avoid rigidity.

When you write-to-release, you will end up learning about yourself in the process (which will help to inform the other types of writing I’ll go over). Oftentimes, you don’t know what you’re holding onto until you let it all out, and the great thing about the practice is that all fear of judgment is nullified. There is only honesty, and that purity of intention is what allows your unconscious to shine through.

Now, there are many ways of going about this practice. Julia Cameron suggests 3 full pages of freehand writing. I know another person who writes-to-release on a tablet where the words are deleted after they are written.

I’ve incorporated this exercise in the form of a daily journaling practice, which I’ve kept going since late 2017. In fact, I could attribute much of my contemplative life to the art of writing-to-release, which eventually led to the launch of More To That in 2018. In other words, there was a direct connection between writing in a daily journal and creating a blog that would go on to change the course of my life.

As a result, I have some practical tips I can share on how to effectively integrate this type of writing into your life (some of this is from The Examined Writer, which is a great starting point for those who make writing an integral part of their life):

- Start small. I disagree with Julia Cameron’s imperative to fill out 3 pages no matter what. I suggest you start with the objective of filling out just 1 page in a small notebook, then work your way up from there. You want to aim for consistency across days, and the best way to do that is to lower the initial barrier to entry. (In my case, I started on a 5″ x 8.5″ notebook, and then worked my way up to a 8.5″ x 11″ notebook that I still use to this day. This is the exact one I use if you’re curious).

- Write freehand. This is a deeply personal practice, and the more tangible you can make it, the better. Feel the pen touch the page, and feel how your words flow out from the body that holds your joys, sorrows, and everything in between.

- Do it in the morning. I tend to get the best results in the morning because my mind is fresh and ready to get moving. When I do the practice at night, it tends to feel more like a chore because I’m tired, which takes away from the intention of why I’m doing it in the first place.

- Use a daily reflection book for inspiration. In the beginning, it helped for me to have a short reflection from a respectable figure that would kick off my journaling session. There are many books out there that have the “1-reflection-per-day” format, but here are some I’ve used over the years:

- The Book of Life by Krishnamurti

- A Calendar of Wisdom by Leo Tolstoy

- The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday

- Show up each day. This is the most important tip of all, as writing-to-release is incredibly powerful once you do it over sustained periods of time. Not only will you have a therapeutic outlet for your thoughts and moods, but you’ll also have a clearer picture into how you think.

And that’s precisely what the next type of writing is all about.

2. Write-to-think

If there’s a unifying theme across some of the world’s greatest thinkers, artists, investors, and founders, it’s that they spend a lot of time doing two things: reading and writing.

Reading makes sense because you can draw upon the knowledge and wisdom of those who came before you, which increases your odds of success if you can integrate these lessons into your life.

But why writing? What about organizing your thoughts into the written word makes for such a reliable contributor to one’s success?

Well, this is where the second form of writing comes in.

If you ask writers why they write, you will likely hear some version of the fact that it clarifies their thinking. But you may wonder why this is so specific to writing; after all, doesn’t speaking and having conversations also help with this?

Here’s the thing. Articulating your thoughts out loud does help, but it’s nowhere near as effective for one simple reason:

You can’t run away from what you write.

I was chatting with a popular YouTuber a while back, and he was telling me why writing is so much harder than recording a video. He said that when you’re recording a video, you have more liberty with your argument. If you’ve hit a logical dead-end, you can simply go off on a tangent and discuss something else because you’re not transcribing your thoughts in real-time. You are much more forgiving of holes in your thinking because there’s no trail of holes that are left behind for you to continuously face.

With writing, it’s different. Since you are converting your thoughts into the written word, you can literally see if your ideas make sense as you connect one sentence to the next. If things aren’t connecting, you’ll know that they aren’t, and the sentences you’ve already written will be there to remind you of that.

This is why so many prominent thinkers write. It forces them to make an airtight argument that considers any gaps in thinking, many of which they’ve worked out during the writing process. This is also why many of them advocate for quickly writing a (bad) first draft, as that’s where all the holes in their thinking will be introduced. The purpose of the subsequent drafts is to then fill them in.

Now, you may have noticed that this type of writing is different from the first type, which was writing-to-release (i.e. journaling). Journaling’s main purpose is to release, which means that sound argumentation and syntax is of little relevance. But this is not the case for writing-to-think. With this second type of writing, you need to put effort into reaching a coherent view of a given topic. You’re not satisfied with sounding like a madman because that means you haven’t adequately thought about the idea at hand.

So the difference between the first and second type of writing can be found in this simple reframe:

When you are writing-to-think, do it as if one other person will read it.

That’s it. Not tens. Not hundreds. Just one.

There are 2 reasons why you want to imagine that just one person will read it:

(1) It will lower any pressure for this piece to perform well, but

(2) It will still incentivize you to be coherent because you want to make sense for that one reader.

There is a sense of empathy that comes with writing-to-think. Even though you’re writing to explore and experiment with an idea (which lowers the stakes), you also want the result to be worth that one person’s attention. Your writing stems from a place of introspection, but it will also need to be sound and lucid.

Whenever I don’t know what I think about something, I use this form of writing. In the hopes that my experience may clarify yours, here are some practical ways to go about it:

- All writing-to-think stems from a problem you’re wrestling with, or a problem you want to understand better. So the moment you become interested in a problem, make note of it and say that you’ll write about it.

- Set aside 90 minutes for you to write about this problem. I recommend you to set up a distraction-free environment, and to use software that keeps you focused (I love Cold Turkey Writer for this, and it’s free).

- When you’re ready, start a timer for 90 minutes and begin writing. There is no need to do any outlining beforehand. Remember that you’re writing to figure out what you think, and not to present an idea to many people (which we’ll get into later).

- If you’re feeling lost on how to start, just write out an opening sentence that describes the problem you’re looking to explore, and the potential solution you may offer.

-

For example, a while back I found myself struggling with envy, and knew that I wanted to understand the problem better. Without knowing what I was going to write yet, I jotted this down:

“Today I want to discuss the problem of envy, and how to dissolve it by knowing yourself.”

That’s how my piece, The Antidote to Envy, was born. I ended up keeping a revised version of that sentence in the published version because it flowed well, but you can take the whole thing out if it doesn’t quite fit.

-

- You can write for more than 90 minutes if you’d like, but keep your piece contained to this single session. You don’t want to overthink it; just get it to a point where it’s good enough, do some light editing (I go over how to best do this in The Examined Writer), and then share / publish it.

Writing-to-think is all about iteration and doing it often on a wide variety of problems. The point of publishing is to have a running log of pieces that you can point people to, which acts as a tangible indicator of your intellectual progress.

But at some point (likely sooner than later), you’ll have a desire to share an idea in a way that will resonate with many people. Writing-to-think gave you the building blocks for your thoughts, but you now want to assemble them in a way where an audience can begin to form. Maybe you want to build a business with your ideas, maybe you want to attract like-minded people, or maybe you just want more people to care about issues you find moving and compelling.

Well, this is where you want to use writing as an avenue to creating impact, and that is what the third type of writing is all about.

3. Write-to-present

If I were to do a survey of my readers and ask how they’ve discovered my work, I don’t think it would be through the pieces on my Reflections tab (which is where my writing-to-think resides). And I am 100% sure that no one found my work through my personal journal (writing-to-release), given that it’s not publicly available and even if it were, wouldn’t compel anyone to think my words deserve attention.

Chances are, readers discover More To That through the pieces on the Best Posts section, or the ones that are listed in the Archive. This isn’t coincidental. That’s because these posts were written in a way where I was thinking about how I was delivering the ideas and connecting them in interesting ways.

In other words, I wanted these pieces to act as a beacon for people to find me.

And I knew that the only way to do that was through the skill of storytelling.

This is what constitutes the final type of writing, which is write-to-present. This is where you’re learning the mechanics of resonance, and understanding how to present your ideas so they can stick in your reader’s mind. This is an art that carries different names: marketers will call it persuasion, managers may call it influence, the list goes on. But regardless of what you call it, it all comes down to your ability to tell great stories.

The problem, however, is that storytelling is often taught as an abstract skill that’s reserved for the brilliant few. It may seem like you just have to be a “natural” at it, and if you aren’t, then get ready to study diagrams of Hero’s Journeys and 3-act structures that show you how to map out plotlines and character arcs. Then once you know how to do that, you’ll have to learn how to keep track of “beats” and introduce twists to keep your audience engaged…

To be blunt, this is nonsense, and this kind of storytelling advice applies to the select few. It’s the same kind of intellectual gatekeeping that the 5-paragraph essay was doing by decreasing your curiosity so that you avoid it altogether. If you’re just trying to present an idea in a resonant way (like most of us are), then you need a much simpler and practical approach.

This approach is what I detail in Thinking In Stories, which reveals the simplicity and efficacy of storytelling in the domain of nonfiction. I’ve spent years putting this method into practice, and its principles are found in the very stories that brought you here in the first place.

But as a primer of sorts, here are 6 principles to keep in mind when you’re writing-to-present:

(1) Understand your Storytelling DNA. In the internet era, your greatest asset is your perspective. The issue with most storytelling advice, however, is that it ignores this and goes straight into the tactics and techniques. You need to first review your interests, your curiosities, and your style to determine the foundation of where your stories will come from. Understand who you are before learning what resonates with others.

(2) Take inventory of your problems. People often invent imaginary problems to address in their stories for the sake of building an audience. But people are smart. They can tell when you’re trying to pander to their interests or if you’re riding some trendy wave.

Rather than finding problems for you to address, take a closer look at your own. What problems have you experienced that you’ve gained clarity into? What are some pressing problems you care deeply about now? Better yet, which problems have you always cared for that give them a timeless quality?

Once you’ve identified these problems, then your job is to make your audience care about them as if they were their own (this is a technique I call Problem Framing). The biggest difference between a great storyteller and a mediocre one is the ability to do this well.

(3) Simplify complexity. Complexity is the enemy of resonance. Any presentation that leaves its audience confused is one that eliminates its capacity to spread.

That’s why great storytellers can take any idea – regardless of its complexity – and distill it down to its essence. There are many reliable ways to do this, whether in the form of simple diagrams (like graphs or spectrums) or metaphors that make the idea to easy to understand. The key is to identify the parts of your story that might confuse people, and simplify it down to a shareable nugget that makes it memorable.

(4) Build worlds. This is perhaps the greatest opportunity in all of nonfiction storytelling. People think that worldbuilding is reserved for fictional kingdoms and magical plot lines, but the truth is that constructing a world around your idea will dramatically increase its resonance. I’ve used this so many times in my work, and still feel like I’m getting away with a secret because of how little I see this technique being used by others.

(5) Structure your ideas along an arc. One piece of traditional storytelling advice that’s actually useful is the idea of using narrative arcs. Where its utility fades, however, is when they attempt to show you how to implement it.

Of the many story arcs that are available, there’s one that stands the test of time in the domain of nonfiction. Learn how to plot your ideas alongside that arc so you have a solid understanding of how your piece will unfold.

(6) Write and distribute. It doesn’t matter what kind of storyteller you are: whether you’re an author, blogger, YouTuber, or marketer, you will have to learn the skill of writing. It’s the most reliable way of connecting with others and sustaining those relationships over long durations of time.

As you use writing to craft your stories, you will also have to learn how to distribute them. Understand how to go wide by leveraging what I call Surface Platforms (i.e. social media and video channels), and how to go deep by building what I call a Depth Builder (i.e. a newsletter). Use both to find people and nourish your connection with them.

Each of these 6 principles are necessary when it comes to writing-to-present. If you want to express your ideas and communicate them effectively, you have to tap into human nature and understand what provokes our sense of curiosity. That spirit of novelty and intrigue is what your writing must convey if you want to use it as a vehicle for impact.

That’s why these principles form the basis of the Thinking In Stories curriculum, which is split into 6 modules that do a deep dive on each:

Now, I plan on discussing storytelling in greater depth because it’s such an important skill, but this post is getting quite long. So in the next one, I’ll dive more into identifying the problems you can address in your work, along with a practical framework you can use to reliably generate a starting point for your story.

But in the meantime, remember the 3 types of writing and how you can use them to oscillate between introspection and expression:

There’s no single type that’s more important than the others, as all 3 of them yield huge benefits in the course of one’s life. But if you want to use writing as a way to find your people and connect with others, then writing-to-present (aka storytelling) is the one you want to hone and refine.

And if that’s something you want to commit yourself to, then you know where to go.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts:

Write for Yourself, and Wisdom Will Follow

The Economics of Writing (And Why Now Is the Best Time to Do It)