The Omnipresence of Work

Humankind holds power over its creations for one silly reason:

The mind doesn’t have an off switch.

The mind’s superiority over the iPhone lies not in its computational power, but in its ability to continue thinking well after it has shut the iPhone down. Thought begets thought, and if you allow it to compound enough, it becomes an engine of innovation that produces all kinds of magical things.

There is no end to this march of human thought, as it transcends even death itself. The moment one node dies, many others will learn from the ideas of that node, and those thoughts form the foundation of further ideas to come. This is why the words of dead poets, politicians, and philosophers grow increasingly influential as time runs its course. As Dostoyevsky writes:

People are always saved after the death of him who saved them.

This endlessly growing web of thought has produced many brilliant things, but perhaps the greatest impact it has had on the material world comes in the form of technology. All it takes is one look at your immediate surroundings to see evidence of this.

Almost everything you can touch was once a cutting-edge invention. For example, imagine the first person that was given a cup to drink from. That must have blown his mind with the force of a million supernovas.1

In this case, we were using a simple cup, but whether it’s a cup, couch, lamp, or laptop, every material product shares two common threads:

(1) It was created using resources from the natural world, and

(2) It was created to serve some human function.

Thought is the tool that allows both conditions to be satisfied. It is only through logistical ingenuity that we are able to extract materials out of the Earth, piece them together, and imbue the result with the attributes necessary to create an iPhone. And it is only through curiosity and creativity where the desire to build a machine like this can come about in the first place.

This is where the utility of thought shines. The fact that smart people all around the world are contributing a seemingly endless stream of ideas and insight is what powers technological growth. In this case, the always-on nature of the mind is a key feature of our species, creating products that hopefully increase well-being with each release.

However, we are all aware of the dark side of this progress as well.

If Condition #1 is taken to its logical endpoint, then we will view the natural world primarily for its utility, rather than for its sheer beauty. Martin Heidegger calls this the “standing reserve,” where nature is nothing but a reservoir for us to draw upon to make more shit. We will destroy acres of the forest to make a few more chairs. Ruin fertile soil to find petroleum. Countless hours of manpower and thought will be allocated to this effort, searching for the marginal value one can get from destroying just a bit more.

If Condition #2 is taken to its logical endpoint, then things look even bleaker. If everything we touch in the material world has to serve some sort of function, isn’t it only a matter of time before humans themselves have to serve some sort of greater function as well? After all, we’re all a part of the material world too, right?

Inherent in any technological advancement is the need for deeply laborious work, ironically to create products that make life easier for its users. Humans and their ability to think become the source for labor, and it is commonly believed that this reduces people to mere task-completing drones, voiding them of any unique personalities or characteristics.

We’ve heard this argument ever since the industrialized era, where rows of people were set up on assembly lines, doing the same physical task over and over again until they went home to relax.

We’ve heard this argument in the era of offices, where rows of people were set up in cubicles, doing the same cognitive task over and over again until they went home to relax.

In both scenarios, however, labor and leisure were delineated by physical space. If you were situated within the four walls of your factory or office, it was time to work. If you found yourself within the four walls of your home, it was time to relax. The mind was able to shift gears based on obvious environmental cues, and this delineation created some form of segmentation in one’s work and leisure life.

To say that things have changed would be the understatement of the year.

Many people are now seeing how technological progress has enabled a world where work can be divorced from the office, and married to the home. We may have understood this in theory before, but now we have been forced to see it in action. And for the most part, the technological infrastructure has been sound enough to support this shift at a fairly astonishing scale.

However, through this move, the age-old physical barrier between work and rest has all but dissolved. We wake up, work, wind down, and sleep within the same four walls that used to serve solely as a haven of rest and recharge. The home is no longer an environmental cue to put work aside. It is a place that constantly reminds you that there is always more work to be done.

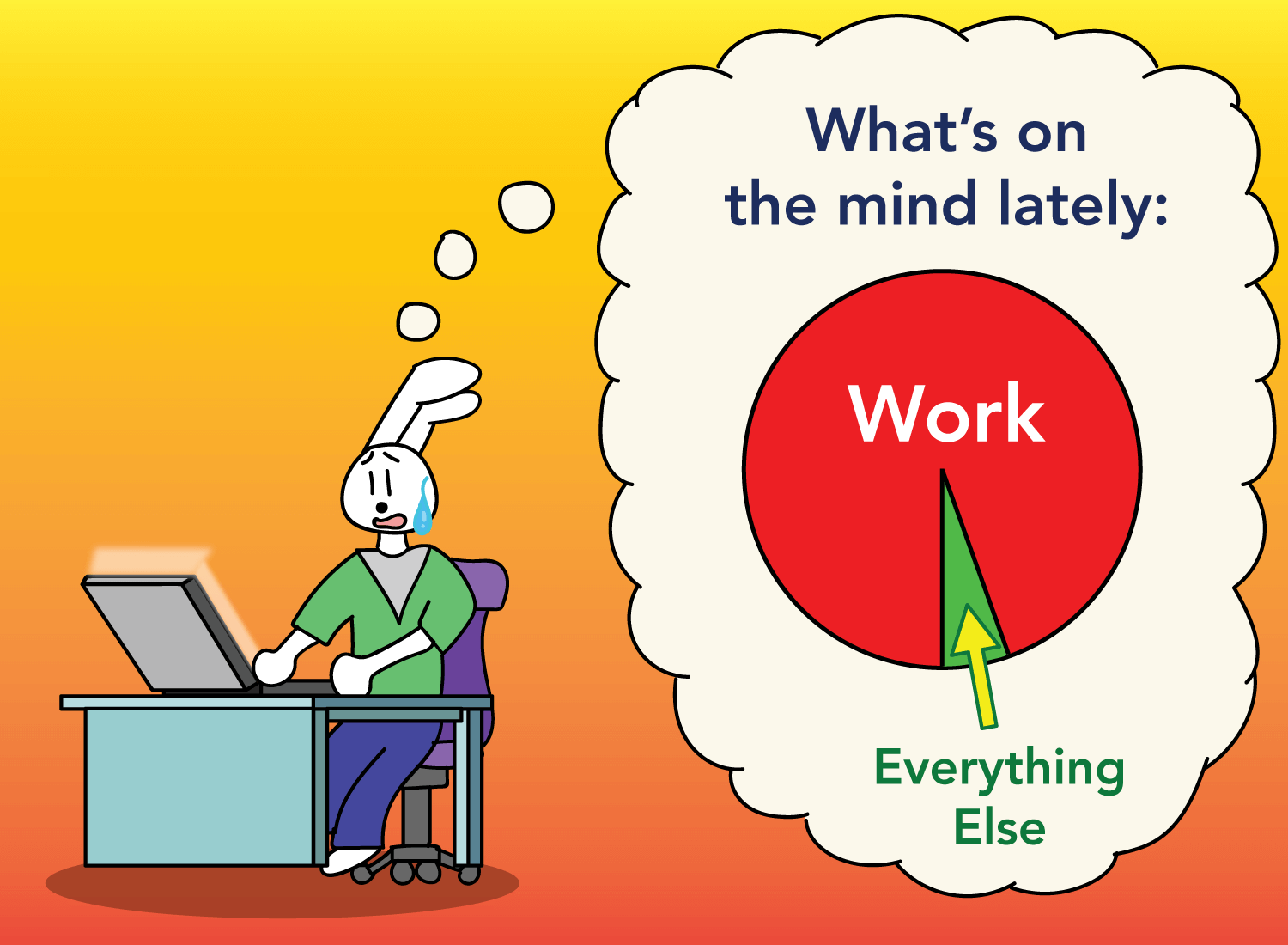

We are now living amidst the omnipresence of work. Even if we aren’t sitting down working, we are prone to continue thinking about it since the physical environment no longer reminds us to shift our mind state. In addition, the always-on nature of our tools means that we are perpetually reachable, as our phones contain the inboxes and schedules of both our personal and professional lives. The question “are you available?” is not really an inquiry about one’s availability, but more so about whether or not one feels like taking that call.

Availability is no longer determined by one’s time, but by one’s attention. The problem, of course, is that our attention is constantly absorbed by the tools we use everyday, making us feel like we’re never truly available. As these tools continue to get nicer, prettier, and more powerful, it becomes increasingly difficult to stop checking them, which further blurs the lines between work and leisure.

I remember when it wasn’t always like this.

Over a decade ago, I had a summer internship where we were all given a Blackberry. This was before the iPhone was a household product, and this bulky-ass, hideous thing was the best option companies had to email their employees when they were out of the office.

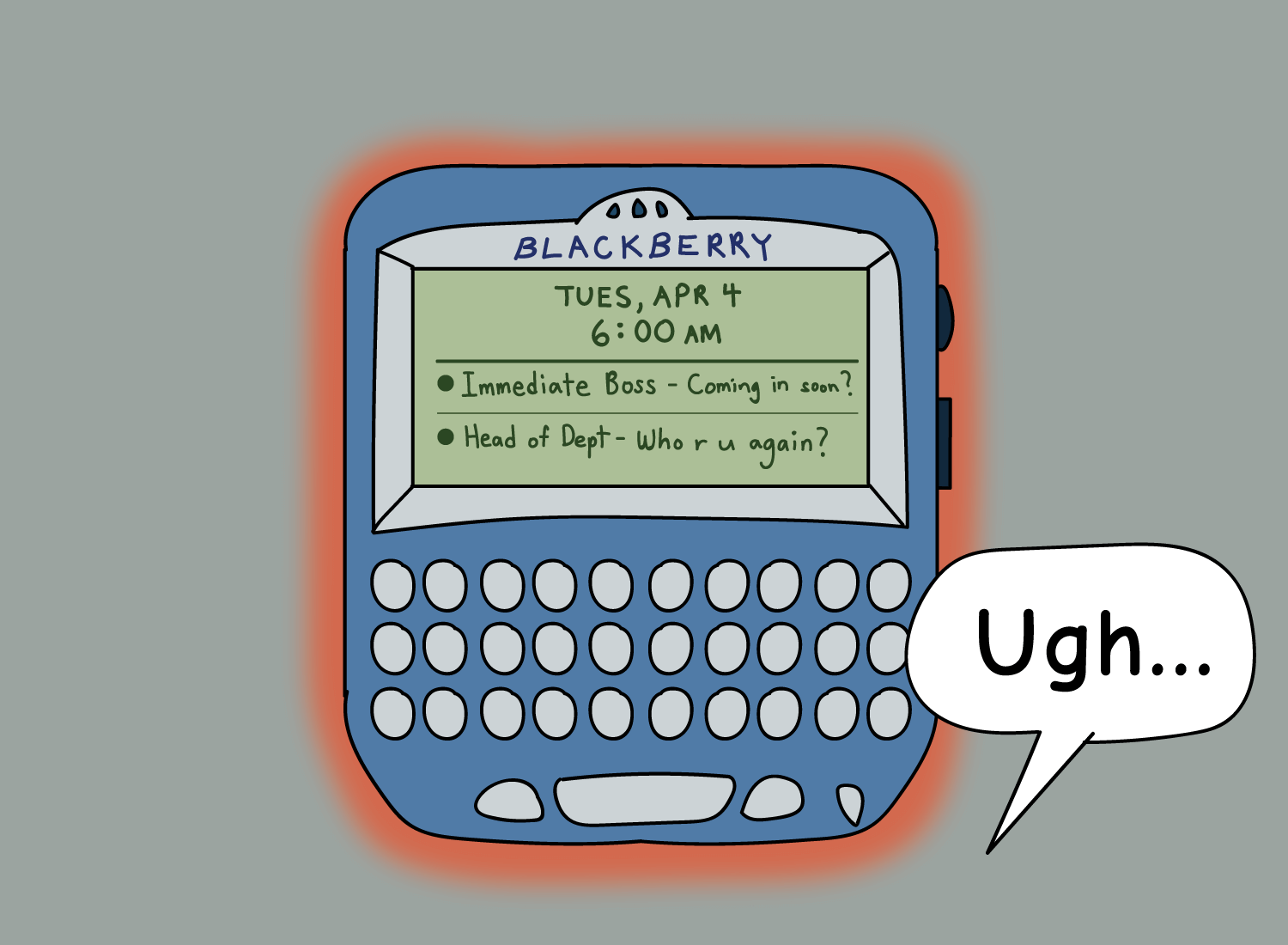

The running joke was that we now had a “leash” that kept us tethered to the whims of our bosses. We heard countless stories about employees enjoying a night out on Friday, only to be pinged by their associate telling them to come into the office to work on a terrible Powerpoint presentation.2

The Blackberry is now a laughable artifact of the early 2000s, but the underlying reason for its existence is more relevant than ever.

Technological progress in the era of knowledge work can be defined by these three things:

(1) Make it easier to connect with others,

(2) Make it faster to get what you need,

(3) Make it pretty and appealing.

The Blackberry did a somewhat decent job at #1 and #2, but it did a terrible job at #3. Even by early 21st century standards, it was a hideous piece of design, and whenever I used it, it reminded me that this tool was definitely for work, and not for play.

Fast forward to today, and things are different. We now have a ton of beautifully designed, amazing tools that allow you to work from anywhere, to reach anyone at any time, and to check on your individual progress and goals. Messaging apps and note-taking tools are multi-billion dollar industries, all of which are defined by their ease of use and their aesthetic appeal.

Work has successfully wrapped itself around shiny toys, all of which are housed in an even shinier phone. Whereas my old Blackberry was an unwilling leash handed out to me and my colleagues, the tools of today are gladly accepted and used by people all around the world. We willingly tether ourselves to the constant demands of the workplace, either by actively working on our projects during the day, or by passively checking on their progress at night.

This then begs the question:

Amidst the omnipresence of work, can our minds ever stop identifying with the constant need to produce?

I’m worried that the answer to this is trending toward “no.”

In my case, I’m finding it remarkably difficult to consciously shift my attention away from work and toward relaxation. It’s as if those two realms can no longer be accessed via a cognitive switch, as the mere presence of my laptop or phone can remind me to check something or queue up another article to read. I know that making some environmental changes can help here, but the existence of this tension is just another sign pointing to the omnipresence of work.

In the case of teams, I worry that all these great tools and technologies are slowly turning us into avatars of productivity, while dimming down our personalities. Communication is no longer serendipitous; it is scheduled in 30 minute increments, which is just enough for a few minutes of small talk, then an overview of what needs to get done. Work is seamlessly distributed to profile pictures on a Slack channel, then collected in pieces by some future agreed-upon date on a shared calendar.

I don’t mean to sound dystopian here, but given this dynamic, it seems inevitable that we start defining ourselves by what we’re able to produce, while everything else goes by the wayside. When Heidegger referred to nature as a “standing reserve” of resources awaiting our usage, it feels like we’re beginning to view ourselves this way as well. We delude ourselves into thinking that the products of our labor are what makes us useful and needed, while things like friendship and love are “nice-to-have”s or “I’ll-get-to-it-when-my-career-has-taken-off” afterthoughts.

The thing is, we all know that work isn’t everything, but the way we spend our attention suggests otherwise. The constant accessibility of work creates the culture of busyness, not just with our time but also with our mind. Not only are our calendars filled with colorful event reminders, but even the spaces in between them are occupied by scattered thoughts and mental exhaustion.

Perhaps the only solution to the omnipresence of work is an intentional shift in cognition, where we shift the mind away from the incessant desire to produce, and into one of periodic contentment. Instead of replying to one-off emails throughout the evening, try picking up the phone and chatting with a friend instead. Rather than trying to brainstorm your next big idea, take the night to relax with a good book or enjoy an entertaining film.

Work, like everything else in nature, follows a circadian rhythm. Intense periods of energy expenditure are followed by requisite periods of rest. The important thing is that the rest must be sustained, and not broken up by intermittent worries and thoughts. That’s like getting 8 hours of sleep, but having it interrupted by the hour. You and I know that nothing productive will be done the following morning.

Funnily enough, the only way to produce our best work is to take the requisite time away from it. It is only through a still and relaxed mind where we can think clearly and make the most of our talents and abilities.

An awareness of this is the best way to navigate the omnipresence of work.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

A fun story about why it’s so important to step away from your workspace:

Creativity Starts Before Anything Is Made

There’s one metric to consider when balancing your inputs with your outputs:

The Release Ratio: How to Make Use of Everything You Know

Work is a fact of life, so might as well make its challenges worthwhile: