Multi-Tasking and Our Greatest Fear

The desire to multi-task is rooted in the fear of death. This may sound lofty, but if you take a moment to explore it, you’ll find that this is true.

Let’s start from the beginning.

We are all born into existence, and almost immediately, we use our senses to interact with the contents of the world. We touch. We smell. We see, but barely. The senses are the hardware that feed information into the mind: our software. That operating system, however, will be in beta mode for quite a while. Neurons and synapses still have to be developed and connected before the OS is ready for primetime, and even after it goes online, it will continuously need updates before the frontal cortex fully develops around age 25.

But somewhere along the way, the mind frees itself from the hardware it relied upon, and something amazing happens. It develops the capacity to think, and can do so without corresponding sensory input. In other words, a thought can form without the body experiencing the contents of that thought. For example, I can ponder the future without actually being in it. Or I can vividly recall a past that the senses experienced long ago. It is for this reason that psychologist Endel Tulving said that “remembering is mental time travel.”

With this development, we are introduced to the world of abstractions. A world where we can know something well before we experience it. A place where we can learn and absorb knowledge without having to discover everything ourselves.

And perhaps the greatest abstraction we internalize is that one day, we are all going to die.

A person sitting in the comforts of his home is burdened with this knowledge. A person entering a war zone for his country is liberated by it. But both know that one day, this abstraction will become very real.

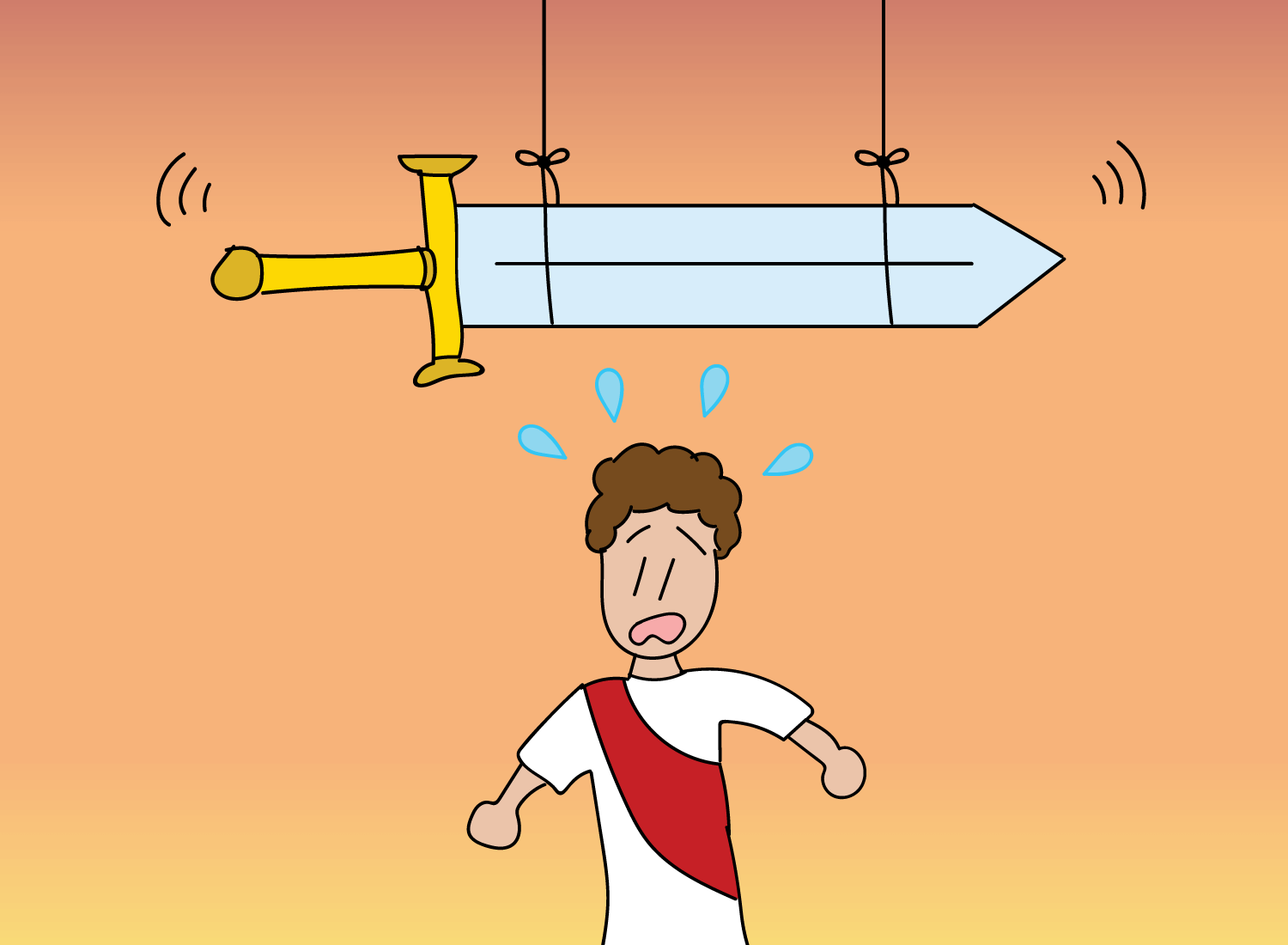

This awareness of an expiration date is further complicated by the uncertainty of the date in question. The Romans portrayed this existential dilemma as the Sword of Damocles, where death is symbolized as a sword that hangs above every one of us. We are fully aware that it’s there, but are unsure of when it will drop. So we better thank the heavens for each day we get, as the next day may not be as kind. (Frankly, it was a clever way of frightening people into gratitude.)

Ultimately, the awareness of our mortality does two things:

(1) It forces us to be reflective when reflection feels like an afterthought, and

(2) It drives us to maximize the precious time we’ve been gifted.

#1 is why people obsessed with their careers or the pursuit of wealth get a fat smack in the face whenever death hovers near. Whether it’s in the form of a personal diagnosis or a loved one passing away, they are forced to confront the stark reality of life, which is this: You can’t ignore your finiteness by working your way through it. You must pause and think about what you’re doing, and whether it’s actually worth doing. Only then can you experience the true fruits of existence.

Interestingly enough, #2 is often at odds with #1. We live in a world where maximizing your time is linked to productivity, where your sense of worth is linked to what you produce. So the adage of “use your time wisely” is often coded language for “make yourself useful.”

Time, in a sense, is yet another abstraction. Or more accurately, our measurement of time is an abstraction. The concept of a second, minute, or hour is a human invention – the product of a thought suggesting that harnessing the power of time will optimize our finite lives.

Here’s something to consider: If we weren’t aware of our own mortality, would we have had the desire to measure time? If life was thought to be a perpetual journey, would we have had the idea to divide that journey into increments?

Of course, no one knows for sure, but I think that we wouldn’t. The way we use time is almost always future-focused, evidenced by the fact that our calendars are only of use looking forward. (The notable exception to this is our chronicling of history, but then again, would we feel the need to record history if we thought that we were immortal?) The division of time is driven by our desire to control it, which is due to our awareness that it’s limited. This constraint is what makes time such a valuable resource, and humans have the general tendency to measure whatever we deem as precious.

But interestingly enough, we figured out that time wasn’t even the most precious resource.

Despite the fact that we all have 24 hours a day, we realized that the way we spent those hours resulted in dramatic differences in outcomes. Person A and Person B both experience the same duration of day, but Person A may be much healthier, much wealthier, and much happier at the end of that day than Person B.

With this realization, we figured out how to hack time. How to temporarily cheat the expiration date that we all have. And it can summed up this way:

Control your attention instead of controlling your time.

This sounds obvious to us now, but our ability to recognize the power of attention was quite profound.

Time follows laws that we have no say over. An hour will be an hour, no matter what. Attention, on the other hand, can be stretched and contracted upon will. We have agency over how we use it, and it gives us a godlike ability to shift our perception of time. An hour may feel like a minute, or it may feel like a day. It all depends on how we use the hour in question.

By using our attention in innovative ways, we learned how to extract incredible value out of preset blocks of time. We used concentration as a tool to power technological progress. We used focus as a mechanism to build institutions and systems. This awareness of attention as a separate entity from time is what differentiated Homo sapiens from any other species on Earth. Simply put, it was what made humans the conquerors of the planet.

But sadly, another defining characteristic of Homo sapiens is that we can never have enough.

We began to think, “If our attention can be stretched, perhaps it can also be fragmented? Instead of investing it in just one thing, perhaps it can be segmented to cover multiple things at once? That way I’m truly maximizing my time.”

This, of course, is what multi-tasking is. It’s the belief that attention can be distributed across many spaces without a corresponding loss in quality. Just like time can be parsed into hours and minutes, perhaps attention can also be parsed into smaller units that can be used to maximize efficiency.

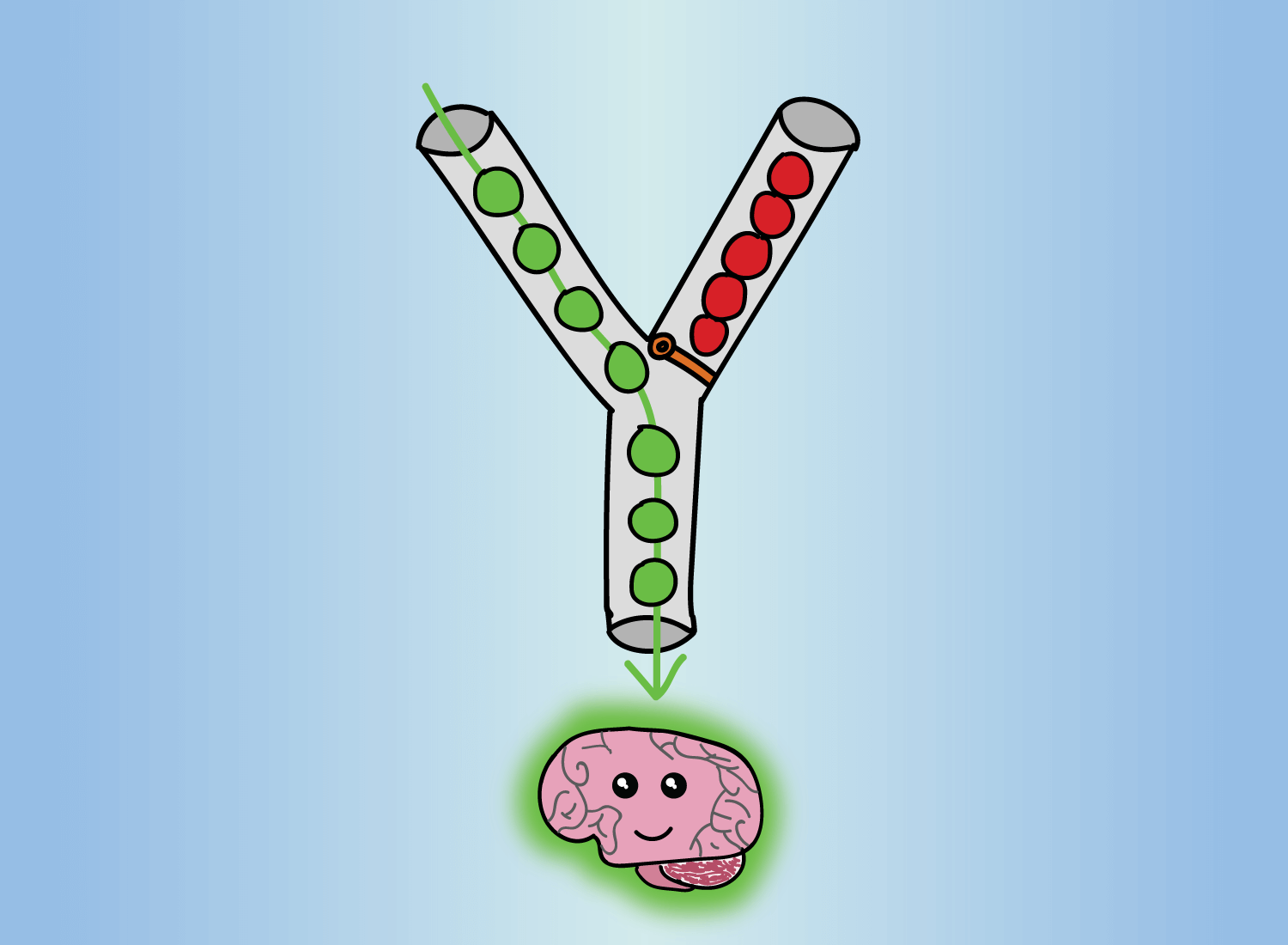

Well, lots of contemporary research has shown that multi-tasking doesn’t really work. In fact, even as early as the 1950s, psychologist Donald Broadbent proposed that the human mind works as a Y-shaped tube when it comes to information processing. Broadbent believed that if the mind takes in two streams of information, only one will be pass through the filter of short-term memory to actually be processed. Everything else will be immediately forgotten, or will be dispensed in due time.

But the greater point to consider here is why we have the desire to multi-task in the first place. On its surface, it may feel like a solution to the problem of busyness. Since we have so much to do on any given day, tackling multiple things at once seems to be a logical approach to take.

However, when we drill down further, we see that the actual issue stems from the desire to control time. The closest thing we’ve discovered to controlling it is through our use of attention, so we try to take this resource and segment it to harness its full power. But in one of life’s great ironies, attention works best when it’s undivided. Its value is not in how widely it can be distributed, but in how narrowly it can define its object of focus.

In a way, we are like Sisyphus, rolling a boulder of responsibilities up the mountain of time, believing that we can overcome everything once we hit an imagined peak. We try these sneaky maneuvers to adjust the boulder a certain way, play with our pacing so we can get to the peak faster, etc. But in the end, the boulder rolls its way back down, acting as a constant reminder that time is not to be defeated, but to be accompanied.

Whenever we focus on one thing at once, we befriend the fullness of time and respect its finiteness. But whenever we segment our attention, we fight a fruitless war against time, hoping we can extract as much value out of it as possible.

Multi-tasking stems from the desire to overcome the finiteness of time. And that is why it is rooted in the awareness of mortality: our greatest fear of all.

_______________