Memory Is the Shadow of Fact, the Artifact of Feeling

Sometimes a moment feels so significant that you’re aware of its importance as it’s happening.

Maybe you’re celebrating the start of a relationship:

Or you’re grieving the end of a long one:

Perhaps you just got an offer call from your dream job:

Or you’re devastated by the news that you’re being laid off from it:

These types of events carry strong emotional charges, and the power of those emotions can seem blinding. That excitement you feel when you first meet a potential partner can color your days and weeks, while the sadness you experience from a break-up feels all-encompassing as well.

When life is blanketed by the texture of these emotions, it can seem like the feeling will persist forever. No matter how many times you’re told that “all things shall pass,” the strength of the feeling is so powerful that it’s difficult to imagine when it will ever become a distant memory.

But inevitably, the constant of time breaks the illusion of permanence.

Time is powerful, but not just because it distances the present from the past.

Time’s greatest power lies in its ability to turn us into historians of our lives.

History is largely an exercise in reflection, and reflection is an exercise in zooming out and seeing the broader landscape. With the aid of time, we can pull back from any given event and survey it objectively, without the intense emotional charge that it originally came with.

So what was once an emotionally blinding event…

…looks like a fainter dome of light…

…revealing itself to be one small node…

… in a vast landscape of connected nodes, all leading to the present moment.

From up here, your life can be viewed as a series of jagged ups and downs, all connected together by various events that were once emotionally poignant. As a historian, you can simply be an observer of these events instead of being caught up in them. Sometimes more time is required to perform this zoom-out, but there will come a point where even the most difficult moments can be observed with this kind of objectivity.

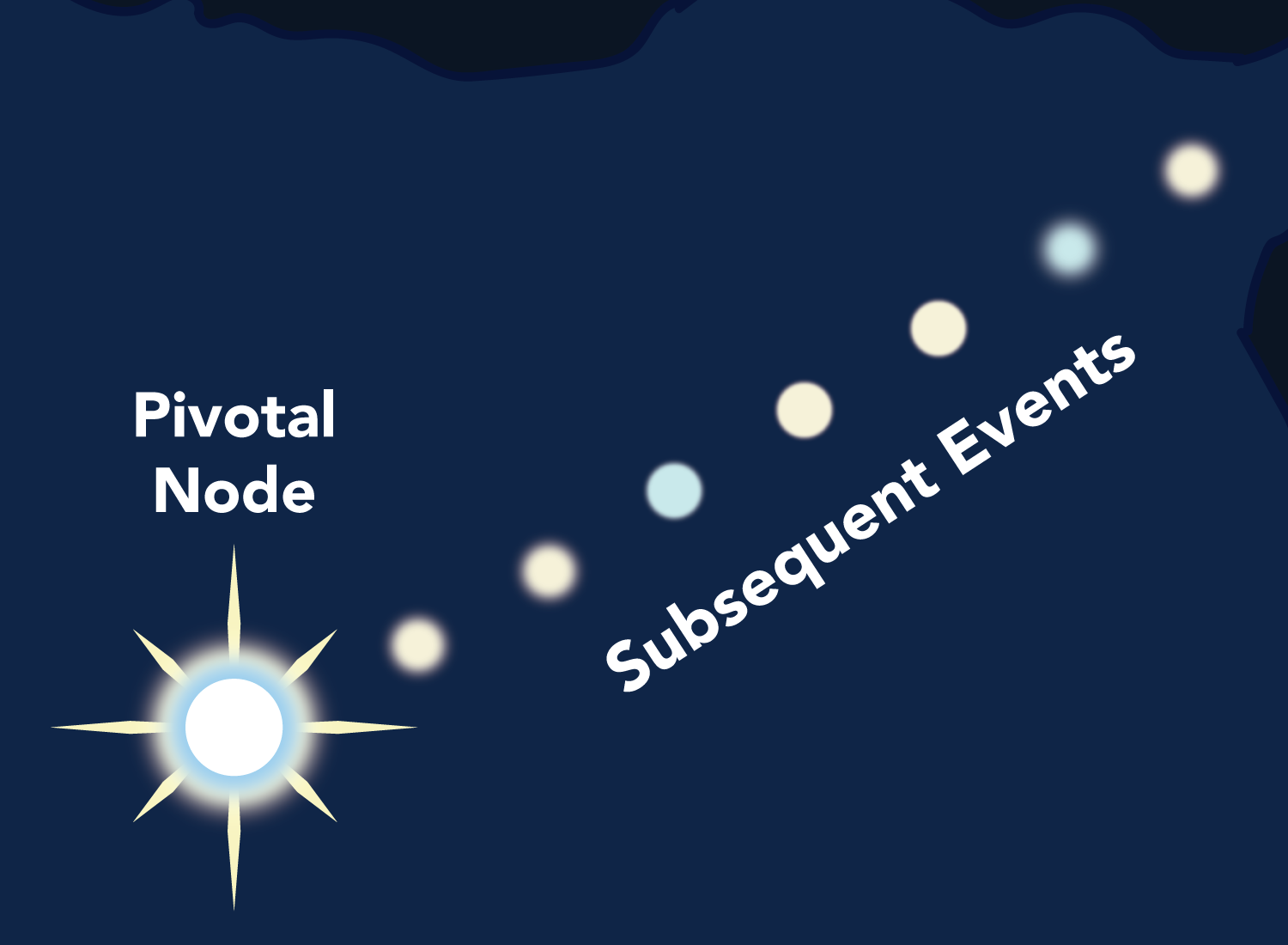

What you will then notice is that in this trail of light, there are certain nodes that shine brighter than others. Sometimes these nodes represent the point in which a downward trend shifts upward (or vice versa), or they just show up in seemingly random places along the path.

I call these bright lights your pivotal nodes, and they represent the events that were critical in shaping the narrative of your existence.

Many things have happened in your life, but chances are the number of pivotal nodes are small. Having a life with fifty pivotal nodes is like watching a film with fifty plotlines; it’s trying so hard to be cool but ultimately makes little sense. Humans are story-driven creatures, and the telltale sign of a sensible story is that it takes the crucial details and discards the rest. The hardest part of making a documentary is not the endless hours of footage, but how it’s all pieced together to tell a compelling 90-minute narrative.

Our lives are defined and told in reference to our pivotal nodes, and when we zoom out to see them in one place, we can see the shared anatomy of each one.

What you’ll find is that each pivotal node has two components:

(1) the circular core, which represents the factual detail of the event, and

(2) the surrounding light, which embodies the feeling associated with it.

Each pivotal node is imbued with both fact and feeling, and one cannot exist without the other.

The core of the node, or the facts of an experience, are the objective details of it. A core may be formed because you were fired from your job, or your partner said that thing to you, or you performed a song for the first time, etc. These facts are the nucleus in which feelings and emotions could accumulate around, and given enough resonance and impact, they can become a pivotal node.

The thing about these facts, however, is that they have to be recalled via working memory. And if there’s anything we know about memory, it’s that it’s terrible. An event that was so lucid and clear a few days ago can become a forgotten shadow in a matter of years. On the day of a gut-wrenching break-up, you may have been able to recount every single detail of it to a friend:

Only to find that a decade later, you’ve forgotten almost everything about how it happened.

The passage of time makes memory unclear, so in order to recall this fact, we tend to direct our attention to its emotional texture instead. The echo of emotion produced from the memory ends up becoming a surrogate for the memory itself. You may have forgotten that hurtful thing your aunt said to you years ago, but you sure as hell remember how upset you felt upon hearing it.

This feeling associated with an event is represented by the light surrounding the core. Some lights shine brighter than the others, but not because the event itself was more surprising. It’s because we have assigned higher degrees of emotional weight to certain events, and not for others. Getting that job at the company may be a life-changing event for one person, and a humdrum one for another. Our interpretation of the event is what gives it its impact, and allows it to direct the trail of subsequent events.

But just like our recollection of facts, our recollection of feelings is also ever-changing. When you’ve zoomed out far enough, you’ll notice that some pivotal nodes with an initially negative texture ended up creating a path that trended upward (positively). That layoff you experienced felt horrible when it happened, but it may have led you to a different line of work that you are so passionate about today.

The same holds true the other way around: a pivotal node with an initially positive feeling may have created a path that trended downward (negatively). That dream job you always wanted may have morphed into your worst nightmare, requiring all your attention and separating you from your family in the process.

What this reveals is that our emotional assignment to events is often unreliable. While we think we desire certain outcomes, it’s impossible for us to know whether they will create a trail of nodes that ultimately lead the right way. When we live a results-driven life, we are focused solely on what we think we want now, ignoring what hindsight will likely reveal to us later. Deathbed regrets are the embodiment of this short-sightedness, and sadly, they are much too commonplace.

Reviewing our personal histories shows us that our recollection of facts is shaky and our assessment of feeling is always changing. However, so many of the narratives we create about ourselves rely upon these two crude intuitions.

Many of your earliest memories create the foundations of who you are today, and how you act toward others. Perhaps you have a pleasant memory where you recall your grandmother smiling warmly at you, feeding you a snack that you’ve loved ever since. This may have become a cornerstone moment that guided your values toward treating elders.

Or conversely, you may have a difficult memory where you recall your second grade classmates laughing at you for bringing your culture’s food over for lunch. This may have made you feel ashamed of your cultural upbringing, and caused you to bend away from it.

These pivotal nodes guide so many of the subsequent perspectives in your life, but it’s quite possible that they’re neither as accurate or poignant as you thought they were. Maybe your grandma was actually annoyed at you for crying so much, and flashed you a strained smile to get you to eat that snack. Or those second-grade classmates were actually jealous that their lunches weren’t as interesting, so they wanted to make you feel bad to mask their insecurities.

However, even if you knew that the facts weren’t accurate, the light of the emotion can still remain. The pivotal node can continue to shine, even if its core has revealed itself to be a mere shadow of what you thought it was.

This is where the depth of feeling can supersede the reality of fact. While this can be helpful in some cases (the smiling grandma example being just one of them), there are many moments where it can be harmful. Holding onto the emotional texture of past memories can make you do some destructive things. You might hold that grudge against your sister for that thing she said years ago, even if you don’t remember what exactly was said anymore. Or you might be scared to put your art out there because that one critic said you sucked, even though that critic thinks that everything sucks.

It’s convenient when our pivotal nodes line up in a way where a nice narrative arc could be drawn, but drawing this arc means that we’re committing to a story that is anchored by shaky facts and feelings. This can make us hold onto a life story with all our might, even if many of the details are faulty and no longer serve us.

Observing the landscape of experiences allows you to see that some pivotal nodes have a shaded core that is kept relevant by the light surrounding it. As the factual details of a moment fade, it leaves behind an artifact of feeling that takes its place, allowing the memory to hold its ground.

But as you live life, it’s important to observe which of these artifacts you’re still holding onto, driving the decisions you make today. Knowing that the feelings associated with memories are in flux, are you okay with constructing a worldview based on ever-changing inputs? Which nodes no longer contribute to the way you view yourself and others today?

Being a historian of your life isn’t just about reflection, it’s also about reframing. Surveying the landscape of experiences is just the prologue to the main exercise, which is deciding which nodes should be highlighted and which ones are to be reevaluated. The memories that were once so crucial to your development may no longer serve you, and only you can dim the nodes that were once so pivotal.

This applies to the present moment as well. Whether you’re currently going through a rough patch or having the time of your life, you can take a minute to pause and reflect on the texture of this experience. There’s a power in knowing that one day the details of the event will fade and the emotions associated with it may change. This awareness allows you to choose which moments are to be held closely, and which ones can slowly fade away into the crevasses of the mind.

_______________

_______________

Reframing the events of life isn’t easy, so here are some posts that could help:

Self-Help and the Smuggling of Values