Make Classics, Not Content

Imagine walking into a gallery of your favorite artist’s work.

You see beautiful paintings lining the walls, spaced out in a manner that allows you to take your time with each piece. Each one is accompanied by a short blurb that describes the background of the piece, its origin, and how it ties in to the rest of the artist’s work.

But what if upon closer inspection, you see that the blurb also emphasizes the piece’s publication date, down to the particular day of the week?

You’d likely find that quite strange, unless the exact day had some sort of historical significance. But given that it doesn’t, you wonder why it was important to include that information in the first place.

With that thought in mind, you move on over to the next painting.

As you admire what’s in front of you, you glance down at the blurb of this work as well. To your surprise, it also states the precise publication date, and it’s exactly one week ahead of the previous painting you just saw.

In fact, as you make your way down the wall, you see that each subsequent painting was completed on the Wednesday following the previous one. It looks like some schedule was being followed, and the artist thought it was important enough for you to know about it.

I don’t know about you, but this would be pretty odd to discover. Because when it comes to my favorite creatives, frequency doesn’t mean much.

I don’t admire Van Gogh because he had a new painting to show every Monday. I don’t think Dostoyevsky is a brilliant novelist because he published a book every 6 months. I don’t like Tarantino because he promises a new film every year.

I like Van Gogh because he created Cafe Terrace at Night. I like Dostoyevsky because he somehow wrote The Brothers Karamazov. I like Tarantino because he fucking made Reservoir Dogs.

The creatives we admire most are the ones that made classics. The ones that spent months creating things that will last for years.

With that said, here’s a difficult question we don’t face enough:

Why do we not hold ourselves to the same standard?

We understand that our favorite creatives are the ones that invest significant time and energy toward a brilliant piece of work. That this devotion to quality is the window into their genius.

However, we tend to conveniently put this dedication aside for our own work. We like to tout “quantity over quality,” and advise others to optimize for width rather than depth. Instead of spending 30 hours working on 1 thing, we tell each other (and ourselves) to work on 10 things for 3 hours each.1

Why is this the case? Why is there an asymmetry between how we assign greatness to others, and how we go about our own work? Why do we care less about Van Gogh’s frequency of output, but focus so much on it for ourselves?

The root of the issue comes down to one word. In today’s creative landscape, our adoption of this word has led us to reduce the whole of one’s artistry into a series of consumable bits.

That dreaded word is “content.”

Content is the commodification of creativity. It’s the piecemealing and packaging of art so that it can be delivered at regular intervals to satisfy the needs of the attention economy. In an era where media is forever abundant, content is what people create to show and remind others that they exist.

In my view, art and content are not synonymous. The purpose of art is to express oneself deeply, while the purpose of content is to garner attention quickly. Art follows a pace that is set internally, while content adheres to expectations that are set externally.

This is why frequency matters so much for anything that deems itself as content. Since the purpose of content is to prevent an audience from forgetting its creator, it is driven by fear rather than curiosity. That fear is what drives the pressure to publish something by predetermined deadlines. It’s what makes someone release something that they knew required more thought and energy. It’s what prioritizes “more” over “better.”

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately because I wrestle with this dilemma quite often. What does it mean for me to create art in a landscape that sings the praises of building an audience? How does that affect the way I spend time with my ideas, and how does that color the nature of my intentions? If I’m cutting my curiosity short to satisfy a deadline, who am I fooling? Myself, the people that read my work, or both?

In order to truly understand something, you have to sit with it, interpret it through various angles, consolidate those interpretations, and carefully map the result onto your existing worldview. Unfortunately, this process can’t be regularly scheduled, and depending on the topic, can take a long period of time. And given that our time is limited by design, we can’t go down the rabbit hole for everything that our curiosity touches. Sometimes playing at or just below the surface is enough.

But what I keep in mind is that the works that have influenced me most are the classics. The works that were obviously inspired by an internal commitment to depth, and not an external fulfillment of timely expectations. If I want to create something that I’m truly proud of, then I know that this type of commitment is a pre-requisite, not an option.

At the same time though, I recognize that there is a utility in regularly publishing your work as well. This is especially pertinent for writing. Writing is an iterative process that refines your thinking with each piece you work on, and there’s something transformative about creating and sharing your ideas consistently. To use a gym analogy, it’s akin to putting in reps for your mind. The habit of showing up regularly is what makes you a better writer, which in turn gives you the tools you need to work on your classic.

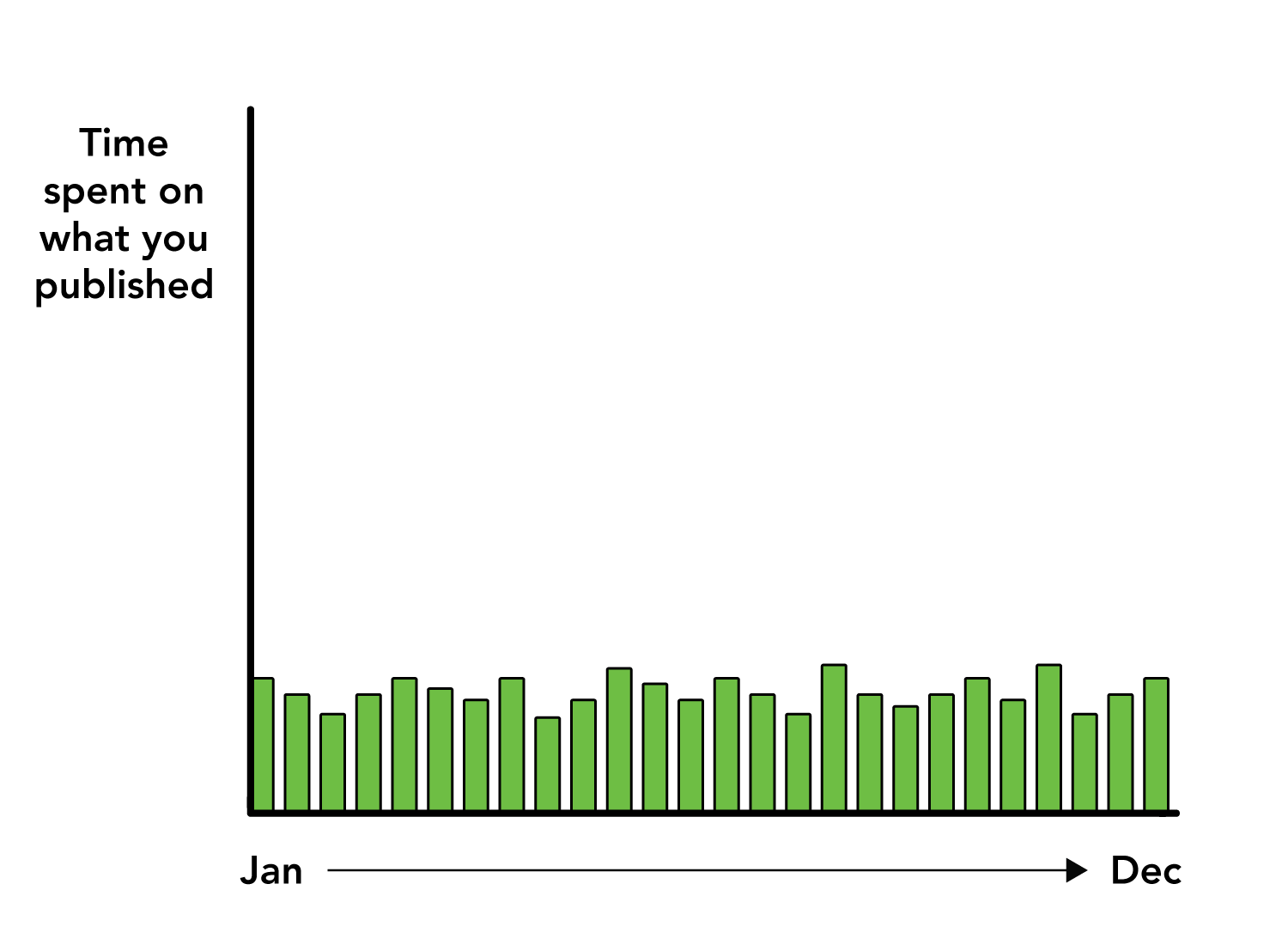

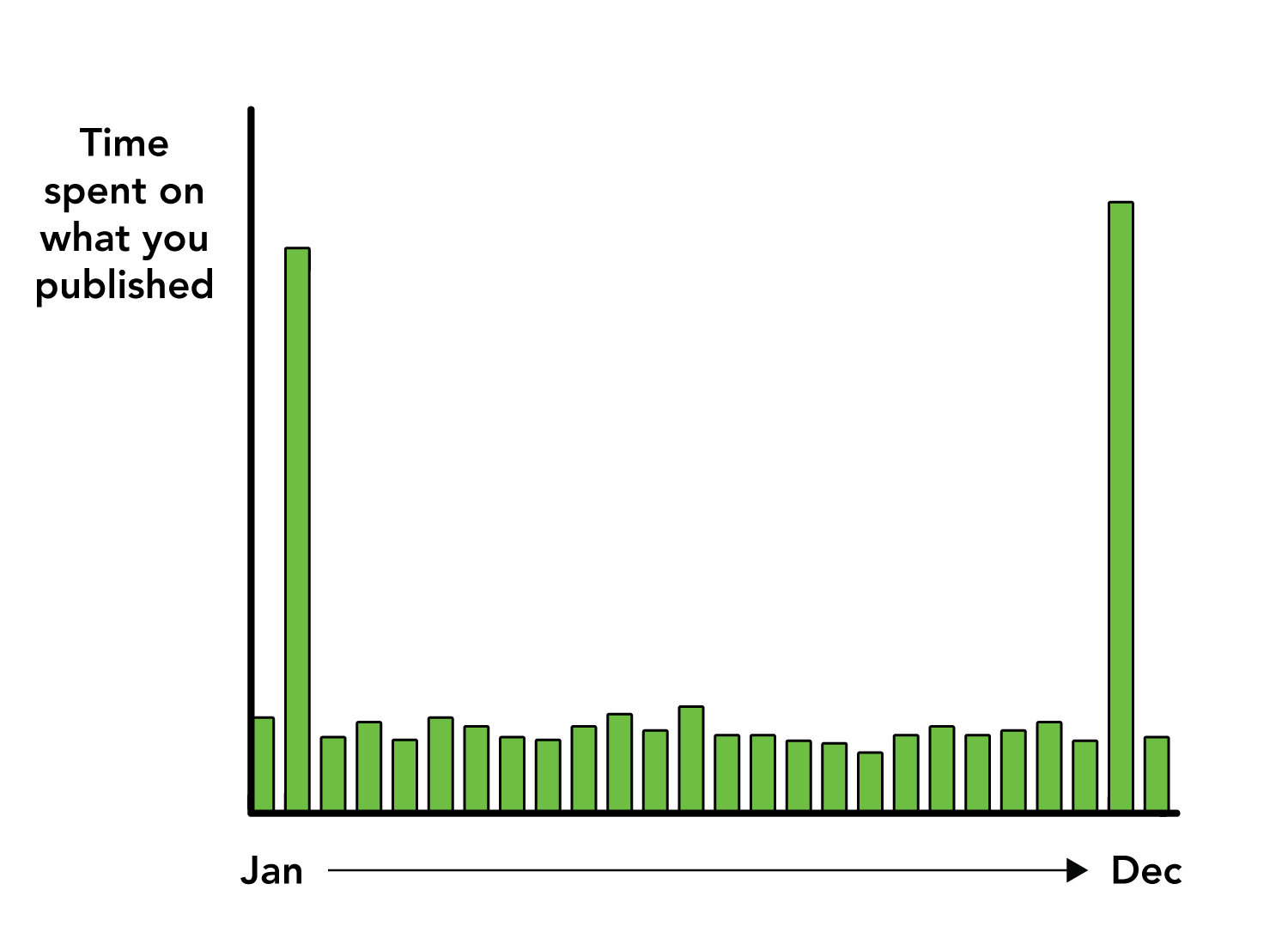

However, if the cadence of your work looks too much like this…

… then it is content. The depth of your ideas is constrained by rigid deadlines, so you will inevitably have to cut your explorations short. By adhering to this type of schedule, you may be a masterful content creator, but will fall short of being a masterful artist.

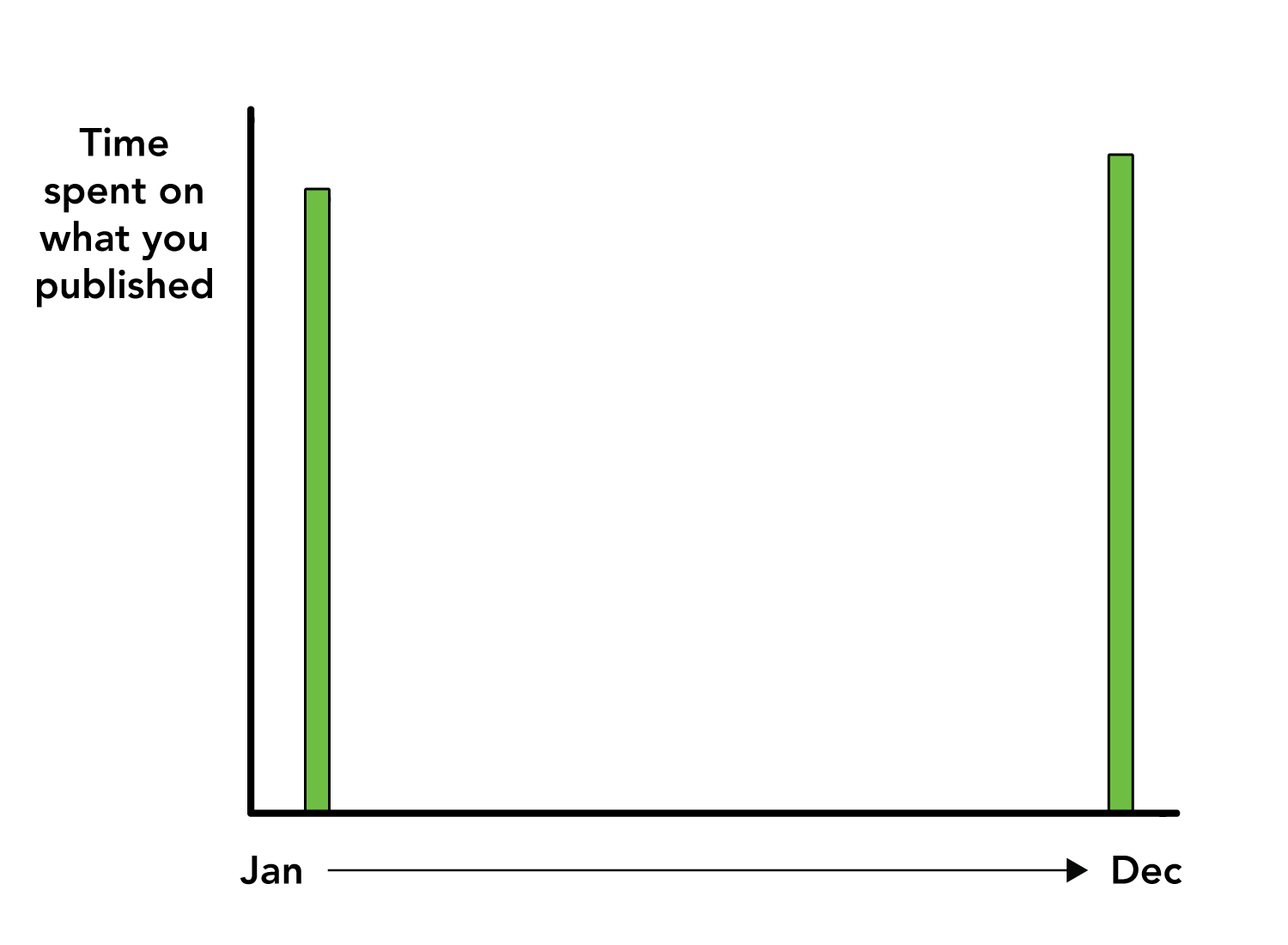

On the flip side, if your work looks like this…

… you may be working on a classic, but you’re missing out on the reps. You may be investing the requisite time and energy to produce something great, but may not have the skills and awareness required to actualize that greatness. After all, in order to create your best work, you have to first do a lot of sub-par work to refine your capabilities.

I find that the optimal cadence looks something like this:

You put in the reps by regularly publishing, then once there’s a topic that you want to dive deep into, you invest the time and energy necessary to create something long-lasting. Your personal classic, if you will. Rather than being bound by the constraints of deadlines, you’re bound by the limits of your creativity, which will surely be expanded as you progress through this big project.

The way I put this into practice is by regularly publishing short-form posts, and then periodically taking a few weeks (or months) to go deep into one long-form post.2 The short-form posts keep me in a playful spirit, allowing me to touch all kinds of topics that I find intriguing. The commitment level is low, while the spontaneity is high. Anything I happen to come across is fair game for a quick exploration.

The long-form posts are my attempts to create personal classics. Works that I’ll be proud of revisiting because I know how much thought and effort went into building them. It’s no surprise that my posts on travel, on money, on the video game of life, and on the sense of self are favorites among readers as well. But even if these pieces garnered zero praise from others, I’d be just as happy with how they turned out. Since no external expectations guided the creation of these posts, no amount of external validation can guide what I feel about the result.

Content is created by optimizing for haste, while a classic is created by optimizing for commitment. To make something you’re proud of, look further than content.

Make a classic instead.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

For a post that contradicts what you just read (since two opposing ideas can both be true):

My personal classics utilize the principles of good storytelling:

The Ultimate Guide to Visual Storytelling

If you’re concerned with achieving originality in your personal classic, this is for you: