Speculation: A Game You Can’t Win

There’s a hiking trail near my place that’s an uphill climb the entire way through.

Despite the arduous trek, the motivating thing about this hike is that the end is always in sight. The top of the hill can be seen from the beginning, so you know that you’ll eventually reach it as long as you keep going.

When I take people on this hike for the first time, everyone is motivated to push through. Even though the hike is fairly steep, no one complains because the finish line is so evident. And as they get closer to the peak, their pace usually quickens as the excitement of the conclusion takes hold.

But once they reach the top, their faces go from this…

To this…

In less than a second.

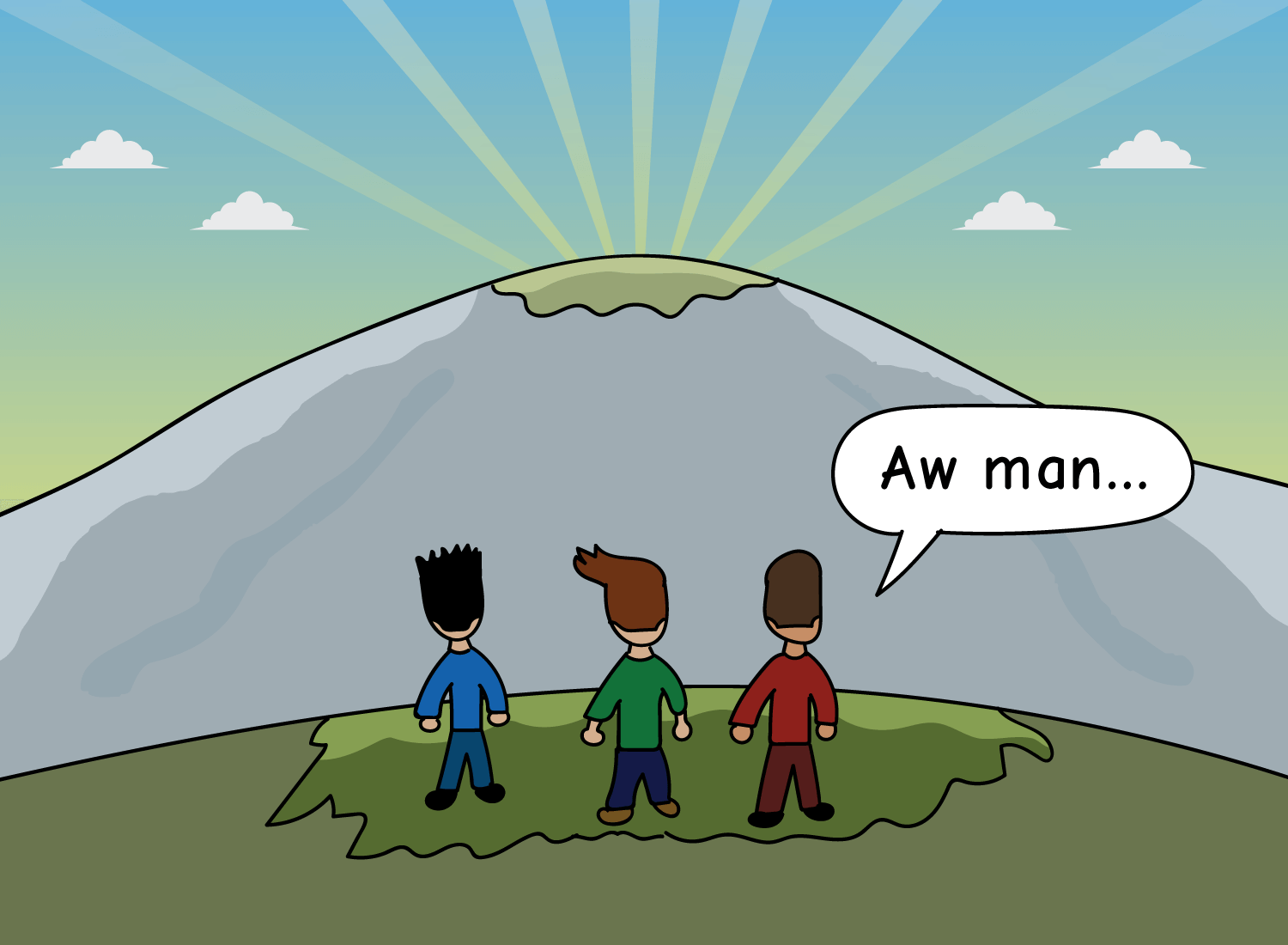

That’s because the peak they imagined wasn’t the peak at all. In fact, it was just a brief resting place for a climb that extended much, much further than they originally thought.

It’s funny because if that really was the top, they would have been quite happy with themselves and the distance they covered. They would want to hang out there for a while, appreciate the view, and revel in the completion of the hike.

But instead, realizing that the top was nowhere near them made them feel disappointed. The fact that they miscalculated the peak made the trek feel underwhelming, despite the great workout they got from the climb. In other words, rather than feeling happy that they exercised, they felt dissatisfied because it wasn’t enough.

There is a strong parallel here with the world of investing.

We’re in the midst of a wild market, with people seeking to convert a thousand dollars into a million within the span of months, if not weeks. The only way to do this is to invest in highly speculative assets and commodities – things that use risk as a selling point, and not as a deterrent. And when you’re willing to lose everything in the hopes of gaining your dreams, the way you view those gains changes dramatically.

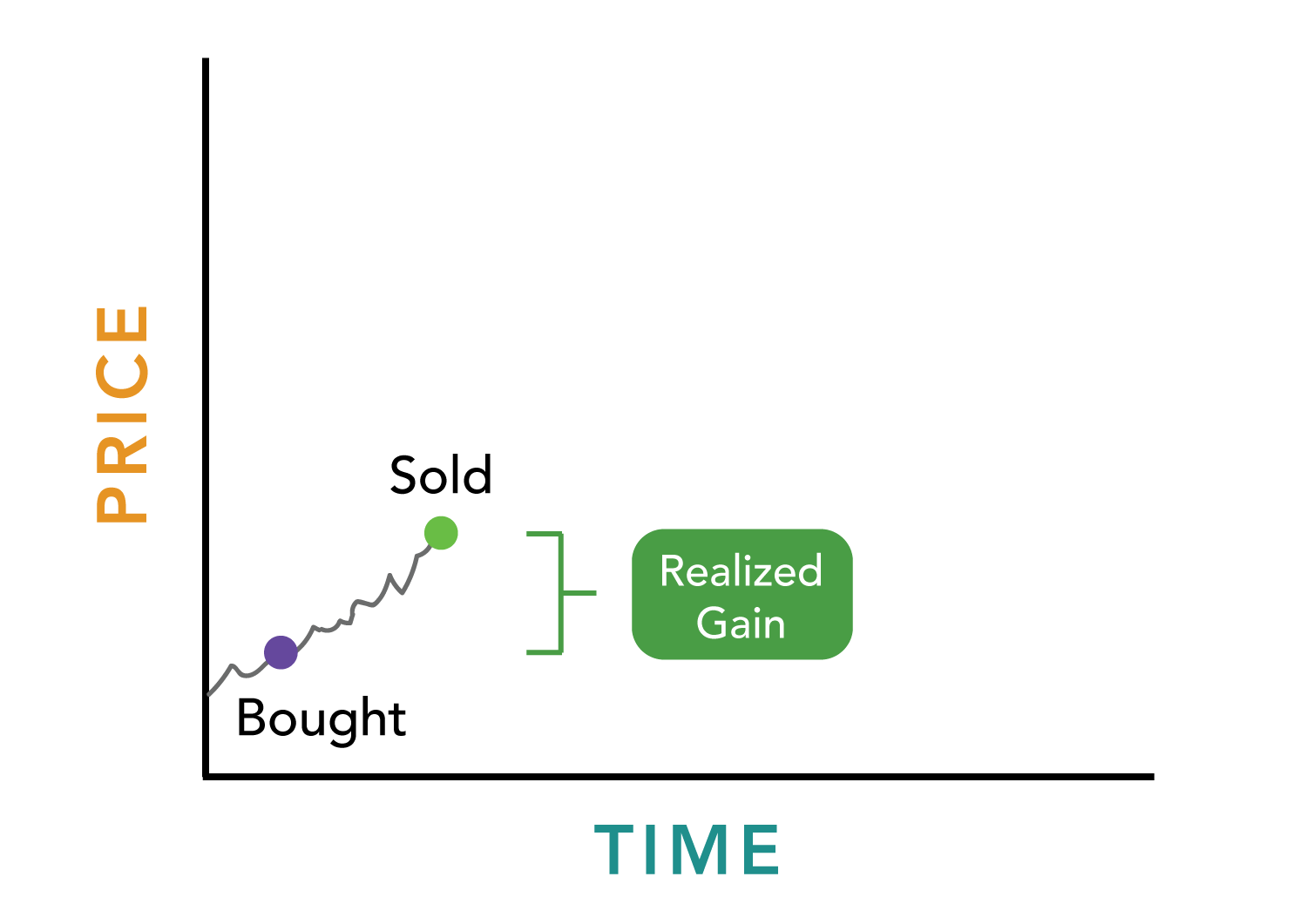

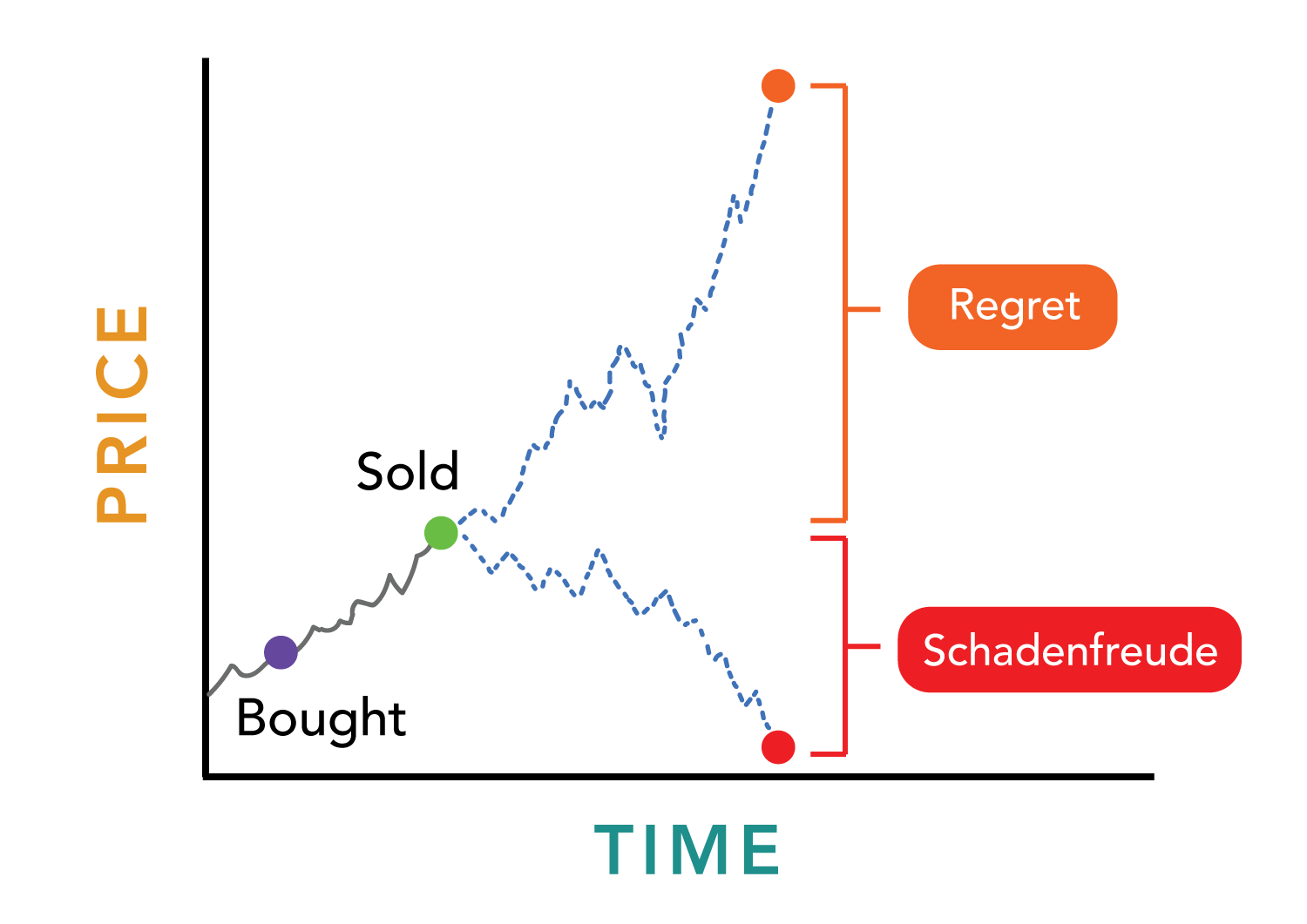

Let’s say that you bought an asset for $1,000 and then sold it for $10,000, representing a 10x return on your investment:

When you sell something, you do so under the belief that this is probably where the peak will be. You believe that this is the top of the hill, and that it’s time to get out before things may slope in the other direction. And by all measures, a 10x return is something to be quite happy about, especially if you achieved this return within a span of a few weeks or months.

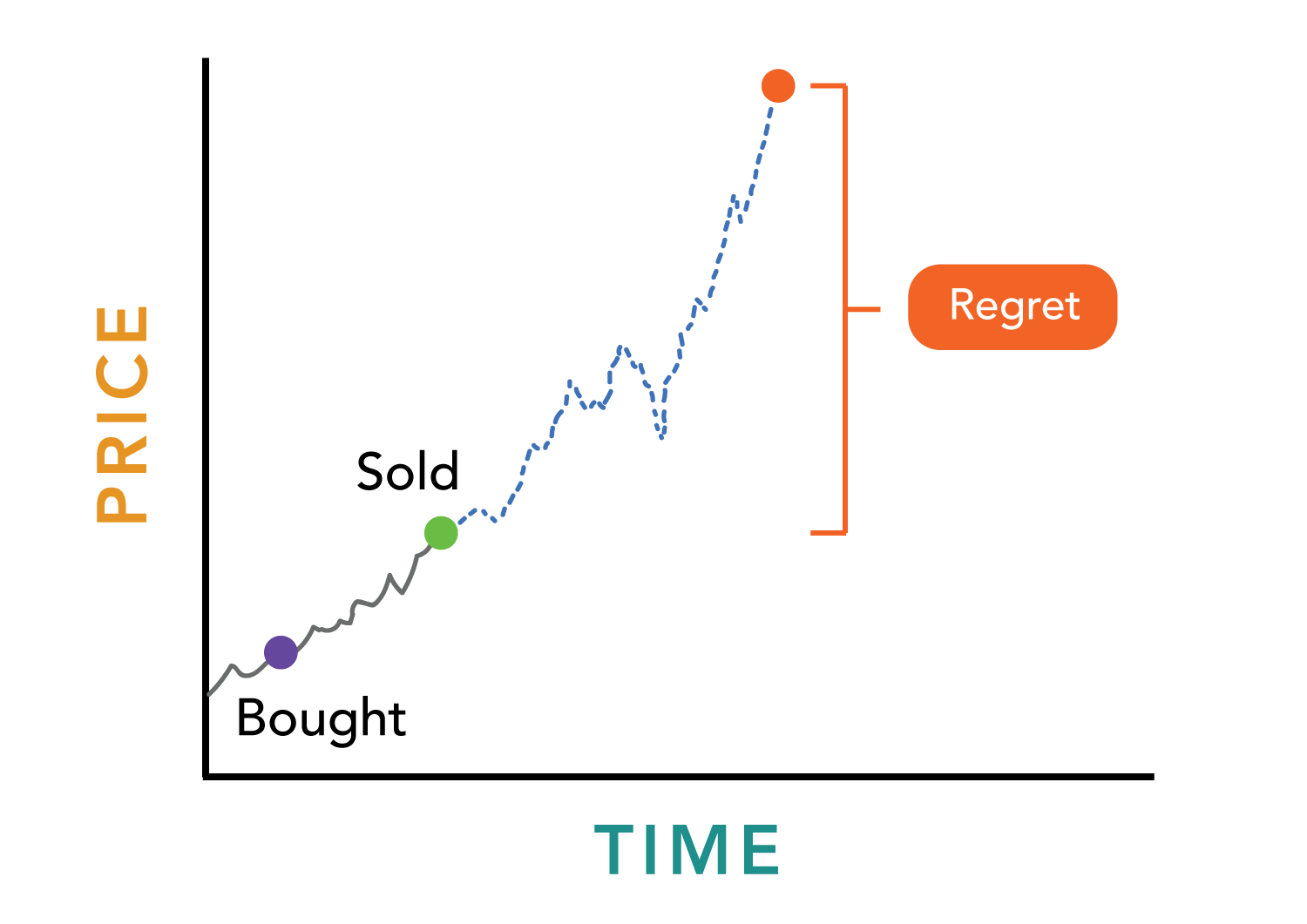

But the thing about highly speculative assets is that they have the potential to do crazy things. Within weeks, their prices can soar to levels that you once thought were unimaginable, revealing that the peak you initially guessed was nowhere near accurate.

And when that happens, you get hit with a heavy tax that is emotional rather than fiscal:

Here’s the thing about speculation: Realized gains feel like penalties when they’re interpreted as missed opportunities. Walking away with a great 10x return will make you feel terrible if that came at the expense of a future 100x return. If the top turned out to be much further out than you thought, then you can’t help but to be unhappy with the gains you actually did realize (no matter how good they were).

This reinforces the dynamic that what you earn is never enough. If making a 10x return turns out to be a painful experience, how does that shape your relationship with money and how you view the world? More importantly, how does that affect your capacity for gratitude? The inability to be thankful for making a solid ROI introduces an entitlement that further distances you from people that are truly in need. How can you connect with the plight of others if you can’t even be happy with something most people would dream to have?

We often view the problems of speculation through a fiscal lens, but it should actually be viewed through a moral one. It’s not often viewed this way, but when you take a moment to do so, you’ll see how pernicious it really is.

Let’s take the opposite side of the coin here and see how it plays out ethically.

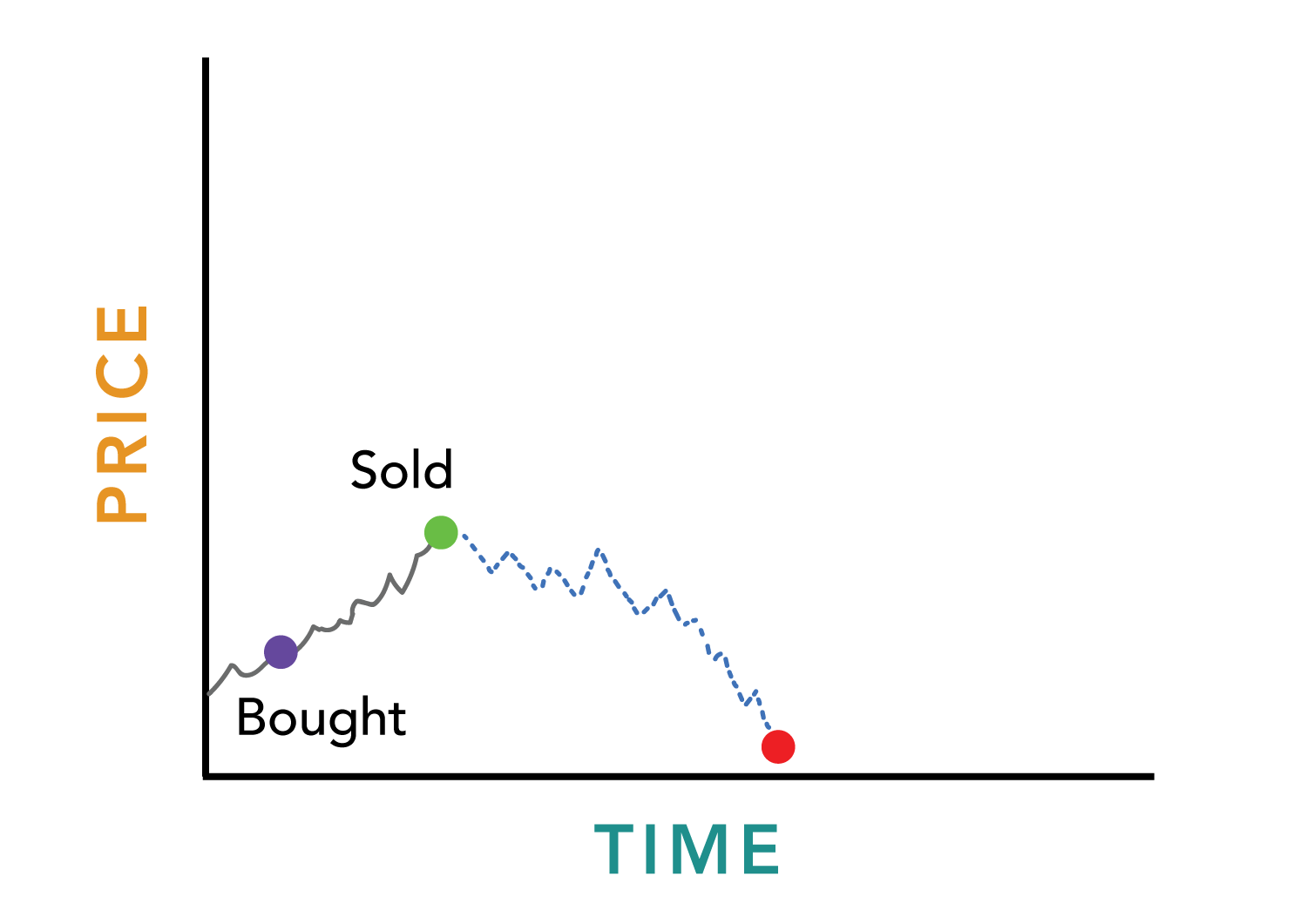

Once again, you buy an asset for $1,000 and then sell it for $10,000, making a 10x return. But what if a few months later, you see that the asset crashes and plummets down to $1?

In this case, you’d likely be elated. You really did predict the top, and got out at exactly the right time. That’s cause for celebration, right?

Well, not really. If you think about it, it’s actually quite sad.

The thing we often forget is that when an asset or stock price crashes, a ton of people are losing a ton of money.1 Savings are decimated, jobs are lost, and futures are thrown into question. There are countless stories unfolding as a price chart bends toward zero, and you can assume that most of them aren’t too pleasant.

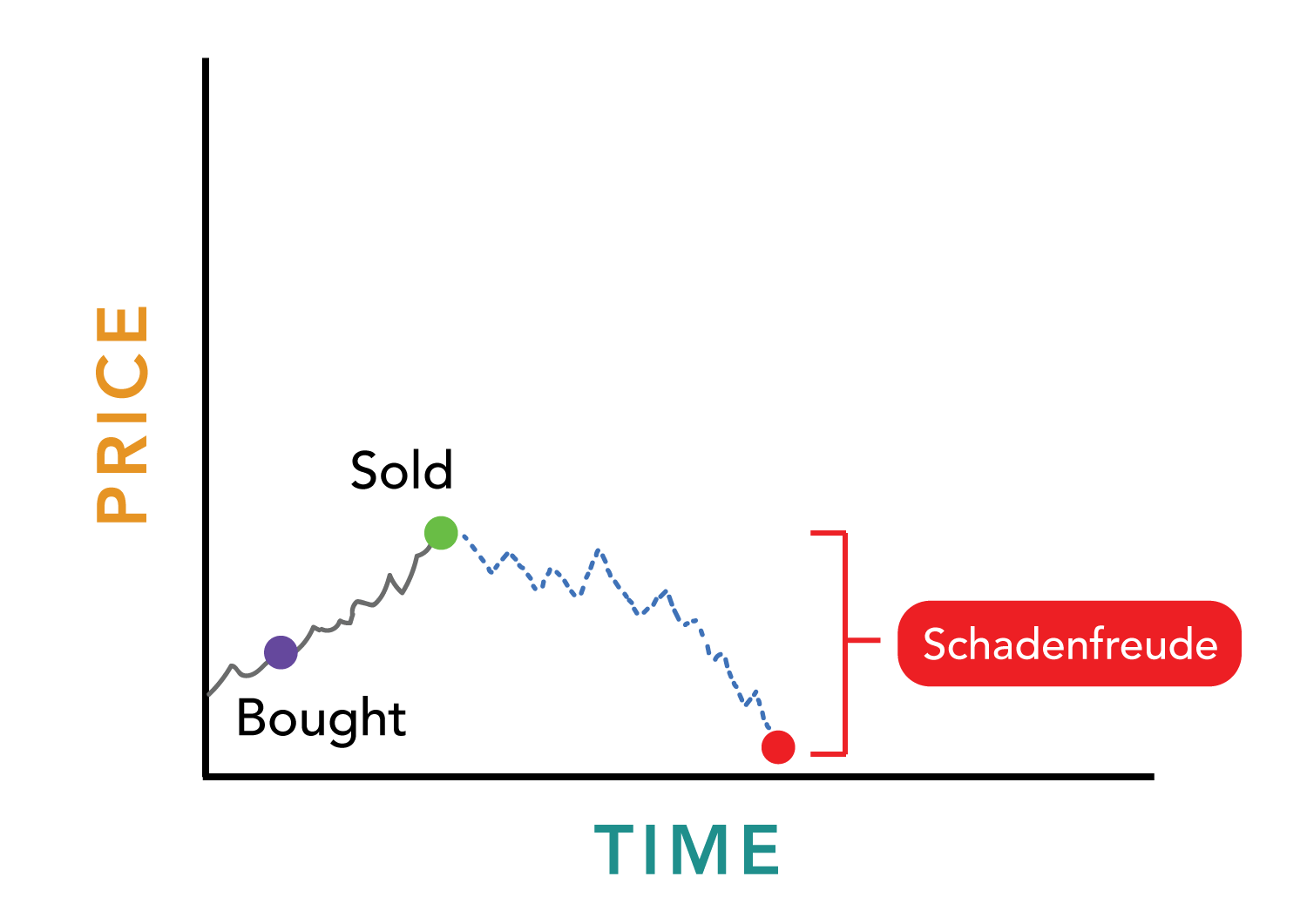

To be happy that you made money on something that crashes is a form of schadenfreude: a German word for taking pleasure at another’s misfortunes. It’s arguably the lowest of all human emotions, especially if it’s directed toward people that just want better lives. Yet schadenfreude is exactly what we’re embodying when we’re elated that our 10x return was realized before things turned sour for everybody else.

It is for this reason that speculation is a game you can’t win. On one hand, there’s the burden of regret resulting from selling too early (or from selling too late at a realized loss). On the other, there’s the schadenfreude you embody by selling right on time. Whichever path the asset ends up taking, there’s a mental tax to be paid on top of any monetary result, and that’s what makes this such a difficult game to internalize.

Personally, I choose not to play the speculation game. Anything with the allure of an astronomical return within a short timeframe isn’t worth the mental (and moral) tension that comes with it. When I invest in things, I do so with a long time horizon so market timing is not a consideration, allowing consistency and compounding to work its magic. What I give up on short-term exponential returns is long-term peace of mind, and to me, that’s a tradeoff that simply can’t be beaten.

But the greatest benefit from this approach is that I can free my mind away from money and invest it into more fulfilling endeavors, such as my creative work. As I’ve said before, financial freedom isn’t about money, it’s about attention. The less you have to think about money, the more free you actually are.

Speculation is the antithesis of that statement. When holding periods are short and expectations are high, almost all your available attention is funneled into your portfolio on a day-to-day basis. If you’re a day trader, perhaps that just comes with the nature of the job. But if you’re doing this to invest your work income, remember how quickly greed and fear can take over your attention. It’s very possible that your work will take a backseat to the realm of your investments, and that just further reinforces how money defines your entire identity.

In the end, a healthy relationship with money stems from how grateful you are for what you have. The constant pursuit for “the next big thing” is a clear indicator that what you have isn’t enough, and it’s worth considering if any amount ever will be.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

A big post on how money shaped the texture of thought:

Speculation is largely driven by what other people advertise:

Envy Is the Cancer of the Soul

A reminder that future time horizons are not promised for any of us: