The Meaning of Life Is Absurd

One of the more daunting things we’ve all experienced is a little something called a “creative block.” It applies to any craft or endeavor imaginable, but we hear about it most frequently in the domain of writing.

Our linguistic overlords at Merriam-Webster define it as such:

It’s a pretty straight-forward definition, but it misses one crucial part, which I’ve added below:

I recently found myself with this “psychological inhibition,” staring hopelessly into a digitalized blank page, my heart rate elevating with each repeated blink of the cursor. I knew there was some idea or topic floating around in my mind, but it just wasn’t surfacing high enough for me to grasp it and expand upon it in a fluid way. I was immensely frustrated, and found myself flailing in a sea of despair, trying desperately to latch onto anything that came to mind.

But then another thought hit me that made everything seem so ridiculous. A few days ago, I was in California, packing up my underwear and clothes to get ready for an extended trip abroad. And within a span of mere hours, through the magic of aviation and logistical ingenuity, I was now sitting in a cafe in Korea – a place halfway across the world – stressing out about the fact that I couldn’t get a thought out into a word processor. Decades of human collaboration and technological progress have afforded me the luxury to log onto this cafe’s WiFi network, only for me to flip out about the fact that I can’t think of anything to write for this obscure, illustrated blog.

In the grand scheme of things, many of the endeavors we worry about can seem just as absurd. In the same way we laugh at a dog’s purposeful quest to chase its own tail, the cosmos seems like it’s laughing at our desire to work so hard for yet another promotion, ridiculing us for all the research we do to decide which new iPad to buy, and shaking its head at how much we care about how our stories look on Instagram.

However, the weird thing is that we can’t help but to find meaning in the things that we do, despite the fact that they seem meaningless in the end. Yes, I can understand that being frustrated with writer’s block is pretty ridiculous despite the fact that the world at large is undergoing some pretty serious challenges, but I simply can’t help but to deem my little writing project as being the most important thing for me at that moment.

This asymmetry between our need for meaning and the world’s refusal to entertain it is known as the Absurd, and this paradox is what philosopher Thomas Nagel addresses in his essay of the same name. In it, he delves deep into what causes this unique feeling of meaninglessness we get when we take a moment to examine what we deem important in our lives.

But before going into the crux of his argument, he first details why some common explanations behind the absurdity of life don’t make any sense. Here are two of the most common ones we hear today:

(Common Reason #1) Nothing will matter a million years from now, so our existence is meaningless.

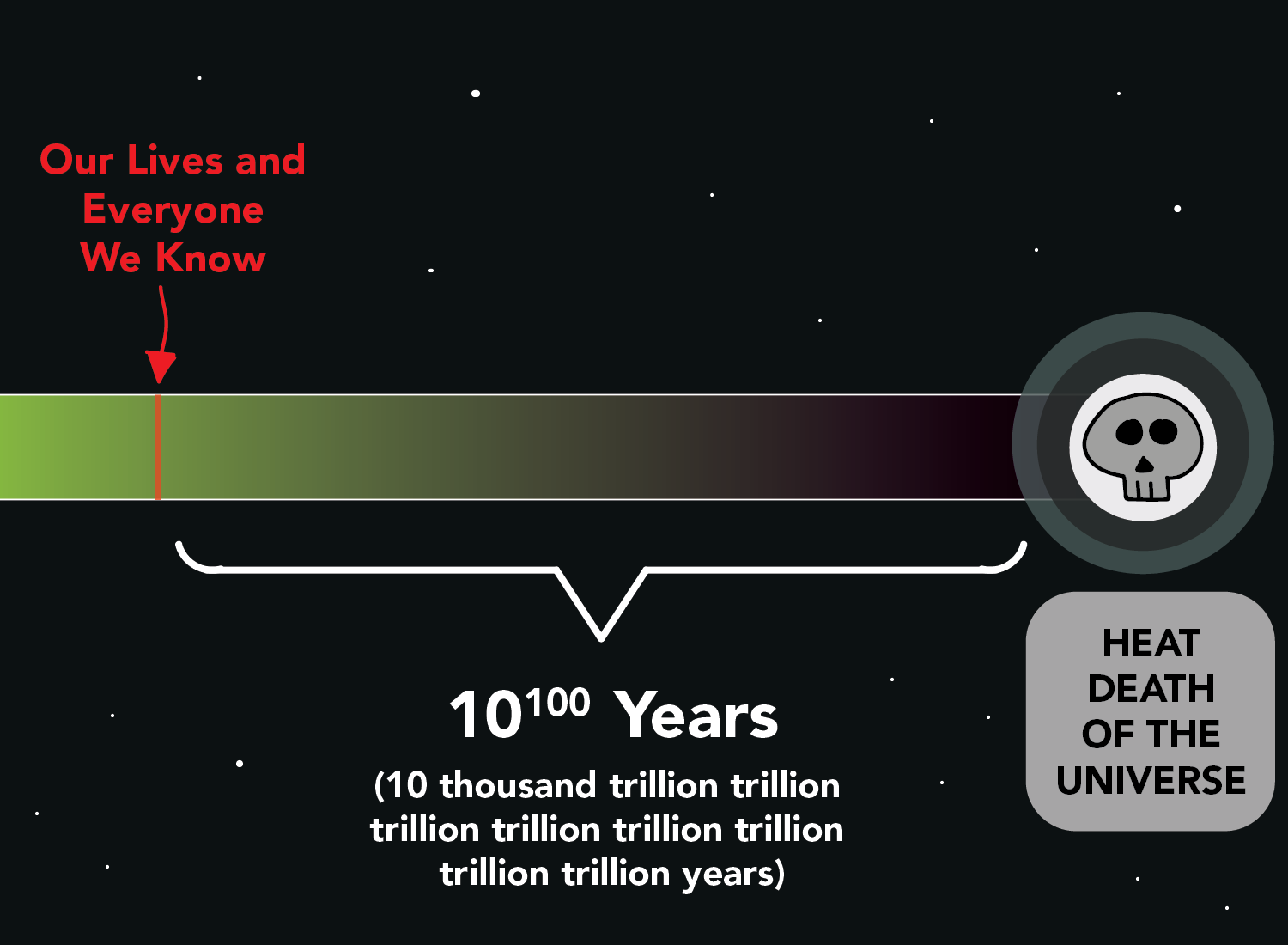

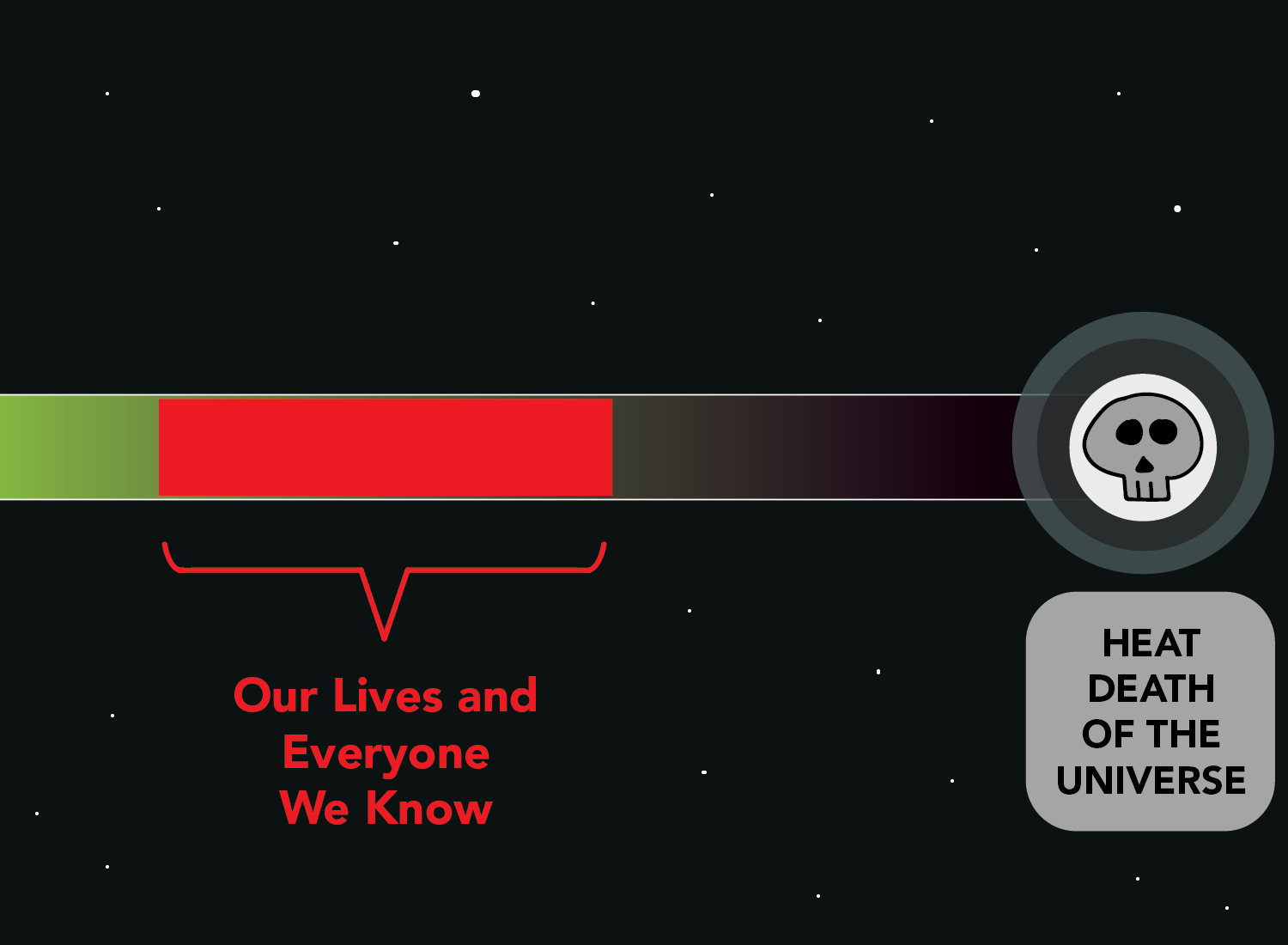

Seeing a picture like this can make everything feel quite inconsequential:

That illustration is a plausible explanation as to why life can seem meaningless, but what if we were able to live a million years?

Damn. Just as meaningless, sorry.

But wait! What if we lived 5 duotrigintillion years (a 5 with 99 zeroes after it), or half the number of years the universe has left until it has no more energy to sustain itself?

That’s a long, long life, but since mortality remains inevitable, how will we know that the things we did for our lengthy existence will matter for the next 5 duotrigintillion years? In fact, our life expectancy could last all the way up to the actual death of the universe itself and it’d still be absurd because there’s no one left to care about our lives in the first place!

There is no magic number of years we can live for that will suddenly imbue all our actions with meaning. Therefore, the number of years on this planet cannot be the origin point of absurdity.

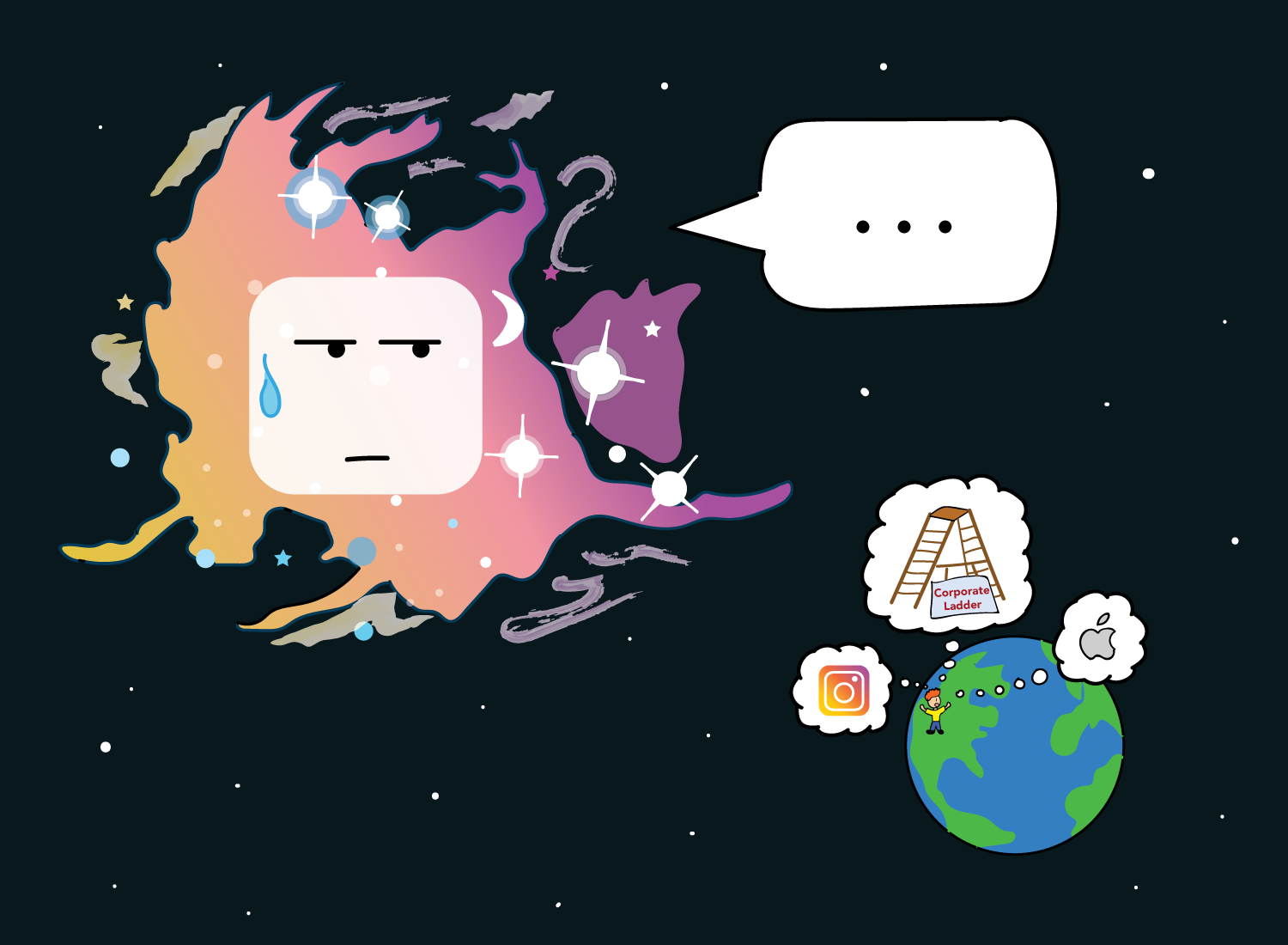

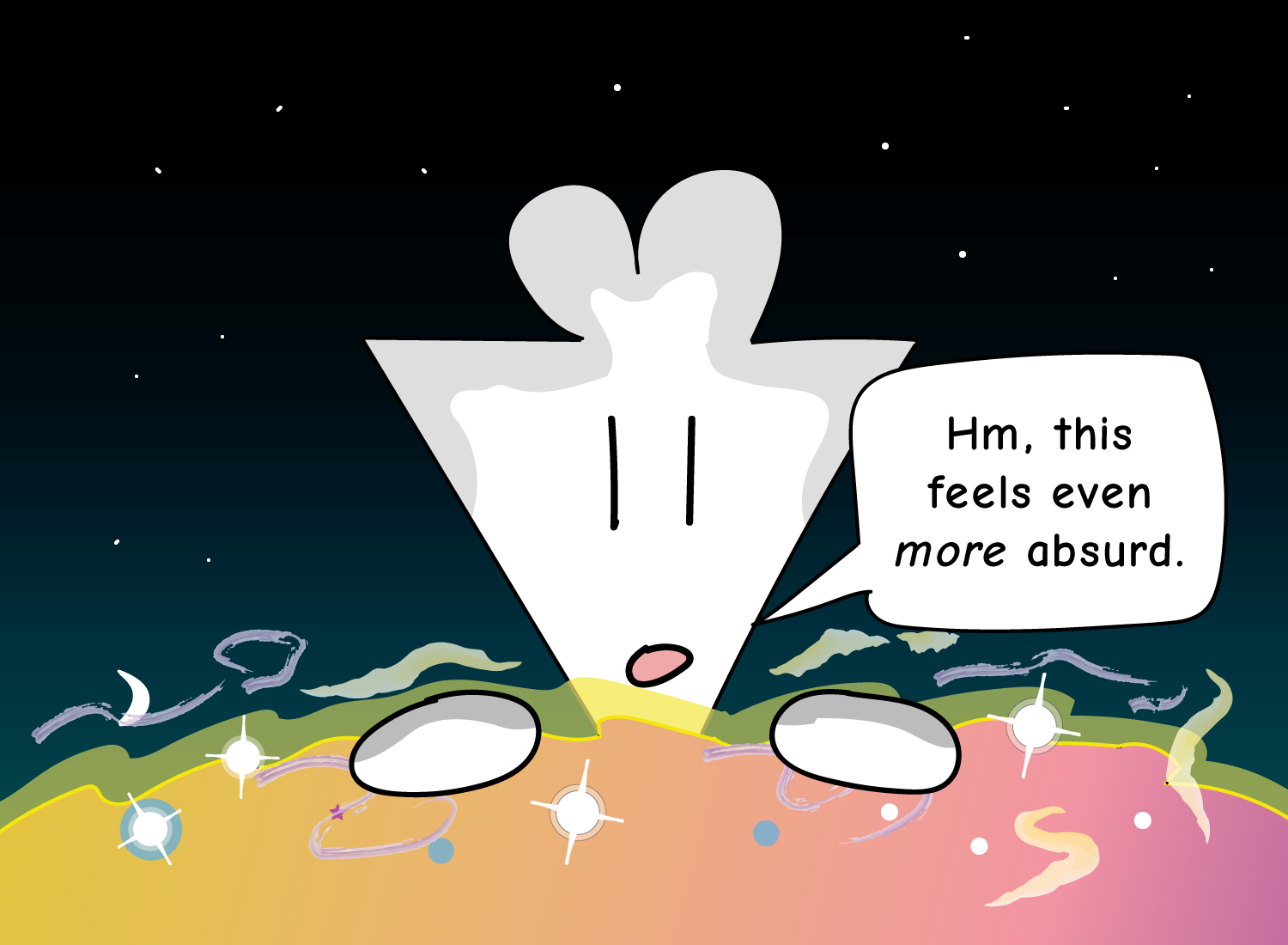

(Common Reason #2) We are all just a small speck of dust in the universe, so nothing matters.

This is the one that usually resonates with me. Whenever I look into a clear sky littered with stars, the smallness I feel can make me think that everything I do doesn’t really matter in the end. So doesn’t the vastness of the cosmos strip away our inherent meaning?

Nagel comically refutes this by asking what would happen if we were just as physically vast as the universe currently is. What if you were a big, lumbering giant that now matches the size of the universe, being able to see the universe as your partner instead of something you’re simply a part of?

While the size of our hamburgers would increase significantly, it’s difficult to see how our fulfillment of meaning would grow accordingly. Being a cosmic giant, towering above all the planets might feel empowering, but this feeling will likely wash away after a while. Nagel says that “[r]eflection on our minuteness and brevity appears to be intimately connected with the sense that life is meaningless; but it is not clear what the connection is.” I’d have to agree.

So if our limited time in the universe and the smallness of our existence aren’t the culprits of the absurd, what is? Nagel has a great answer, but instead of simply regurgitating it, I’d like to reframe it using one of the most ubiquitous (and annoying) hashtags of our time:

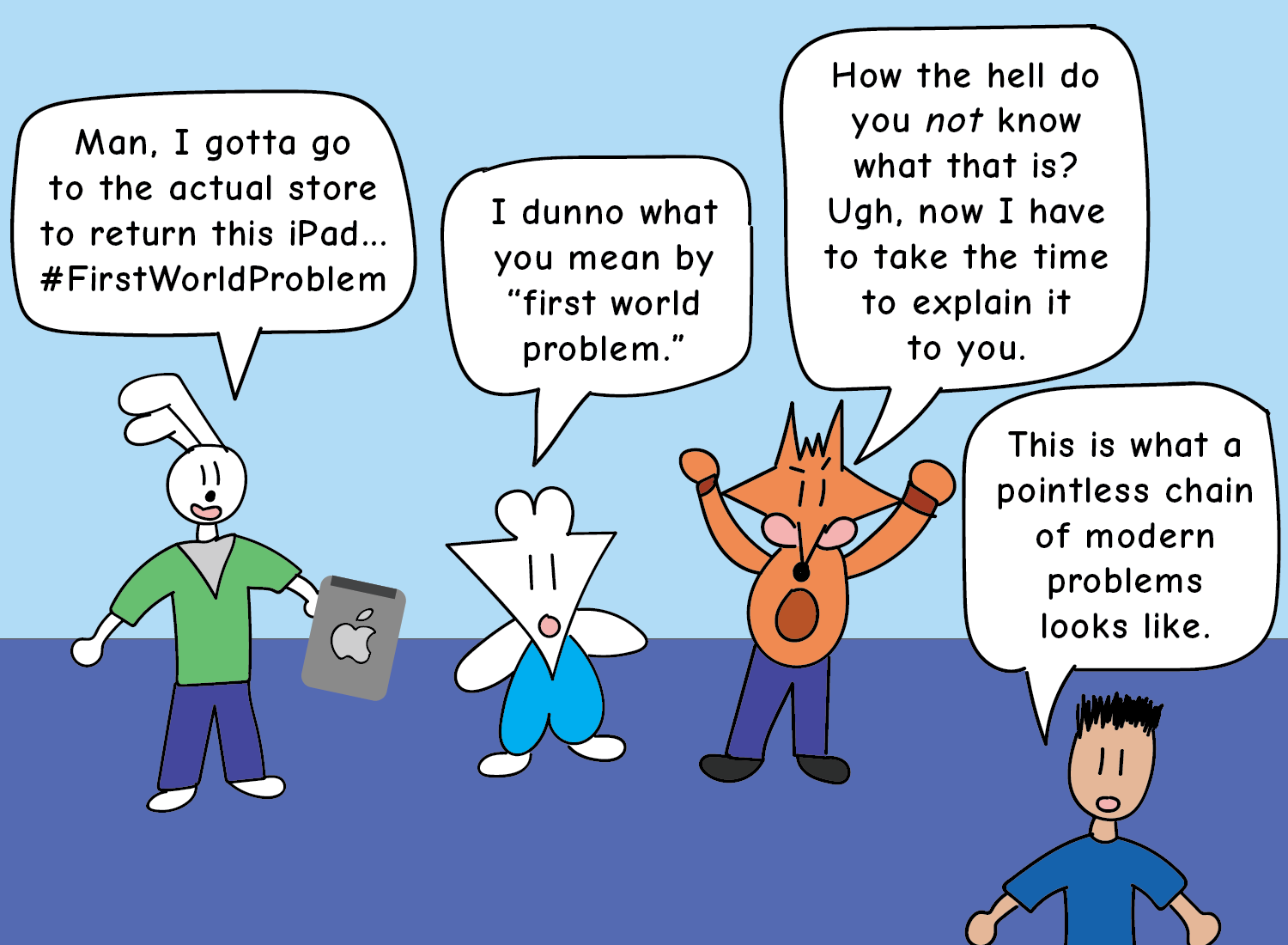

#FirstWorldProblems.

If this is your first time hearing about this meme, then I guess that in itself is a first world problem.

In short, a first world problem is a complaint from someone living in a place with a relatively high standard of living (the United States, Canada, Western Europe, etc.) that seems stupid and trivial compared to truly pressing problems in other parts of the world (countries experiencing starvation, widespread disease, etc.).

We’ve seen the memes, and they are largely comical in nature. From something like this:

To this:

To this:

They really are endless.

While these are designed to make us laugh, there are actually many “first world problems” that appear to be some deeply pressing issues. For example, if you hate your well-paying job because it’s excruciatingly boring and mind-numbing, that seems like a real problem. You can understand that you’re not starving and aren’t in a disease-ridden part of the world, but that thought fails to keep you eternally grateful for this soul-sucking job.

To Nagel, we humans always find ourselves clashing between these two things:

(1) The inevitable seriousness in which we view our lives, and

(2) The ability to view that seriousness as being silly and insignificant.

What makes the whole thing so absurd is that even after we notice the meaninglessness of things, it doesn’t make them any less significant to us.

A first world problem is a meme-ified version of Nagel’s definition. Saying that stupid thing you said at your work holiday party can feel super serious, but you can simultaneously realize that it’s still a dumb, first world problem. Yet even after this realization, it will still remain a problem to you nonetheless! That’s what makes it so damn absurd.1

When we’re zoomed into the small window of our own minds, every little thing matters. How we brush our teeth, what we eat, who we date, how our relationships with family and friends are, how well we’re doing our jobs, what values we believe in… all of this is imbued with seriousness.2

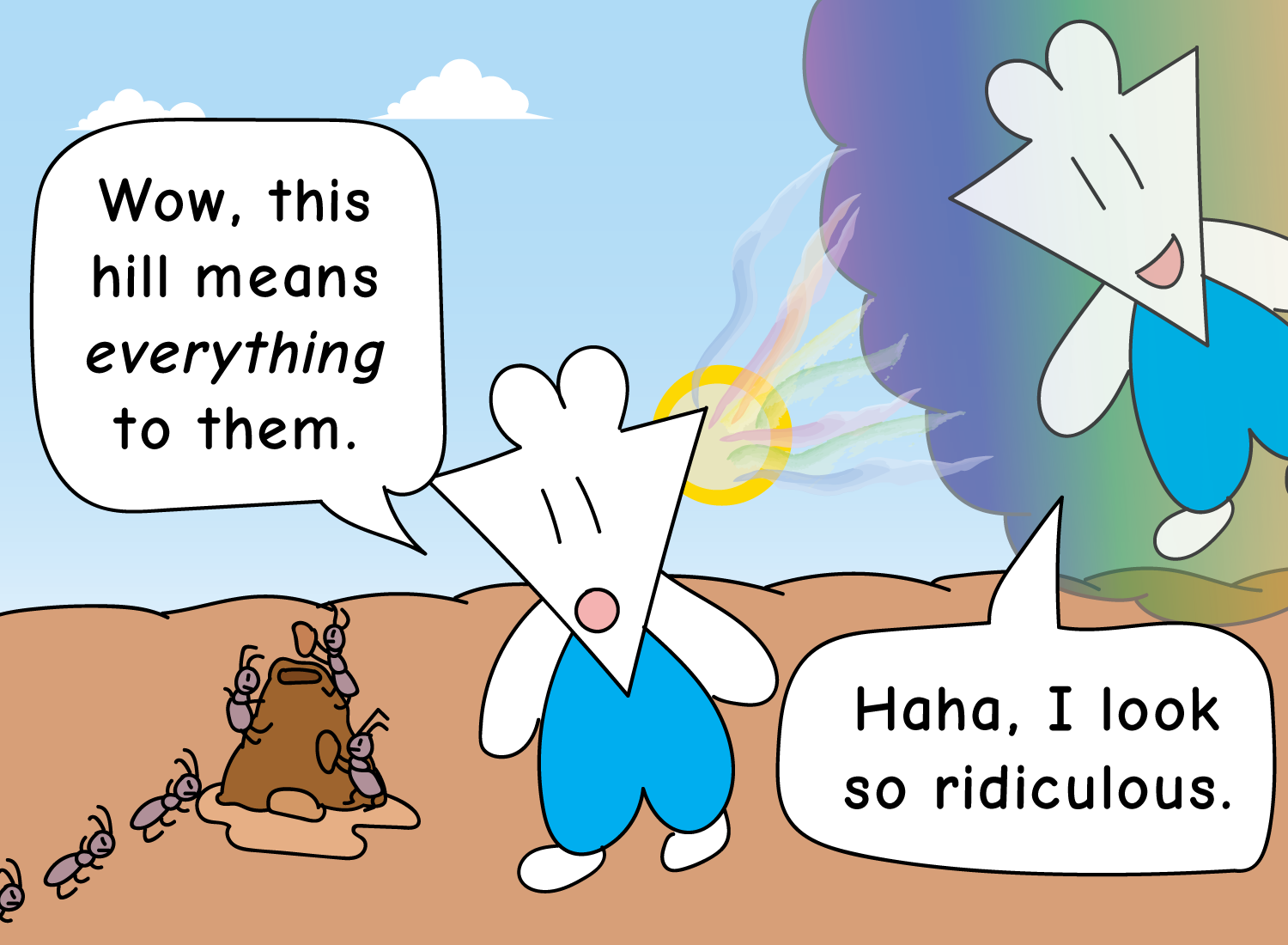

Yet at the same time, we have the special capacity to zoom out and notice that nothing truly matters. We are able to observe ourselves with what Nagel calls a “detached amazement which comes from watching an ant struggle up a heap of sand.” This bewildering realization of meaninglessness is a unique human ability that brings about the absurd.

Sometimes the absurdity of life scares us, as it illuminates that our search for meaning won’t give us any real answers.

To avoid accepting this condition, we like to join organizations and enterprises to feel like we’re part of something greater than ourselves, often in the pursuit of truth. We subscribe to the advance of science, join the world’s religions, represent political parties, and march on the streets in the name of revolution. While this helps to create a sense of purpose, Nagel argues that the absurdity continues because we are the ones that give these enterprises meaning, and not the other way around.

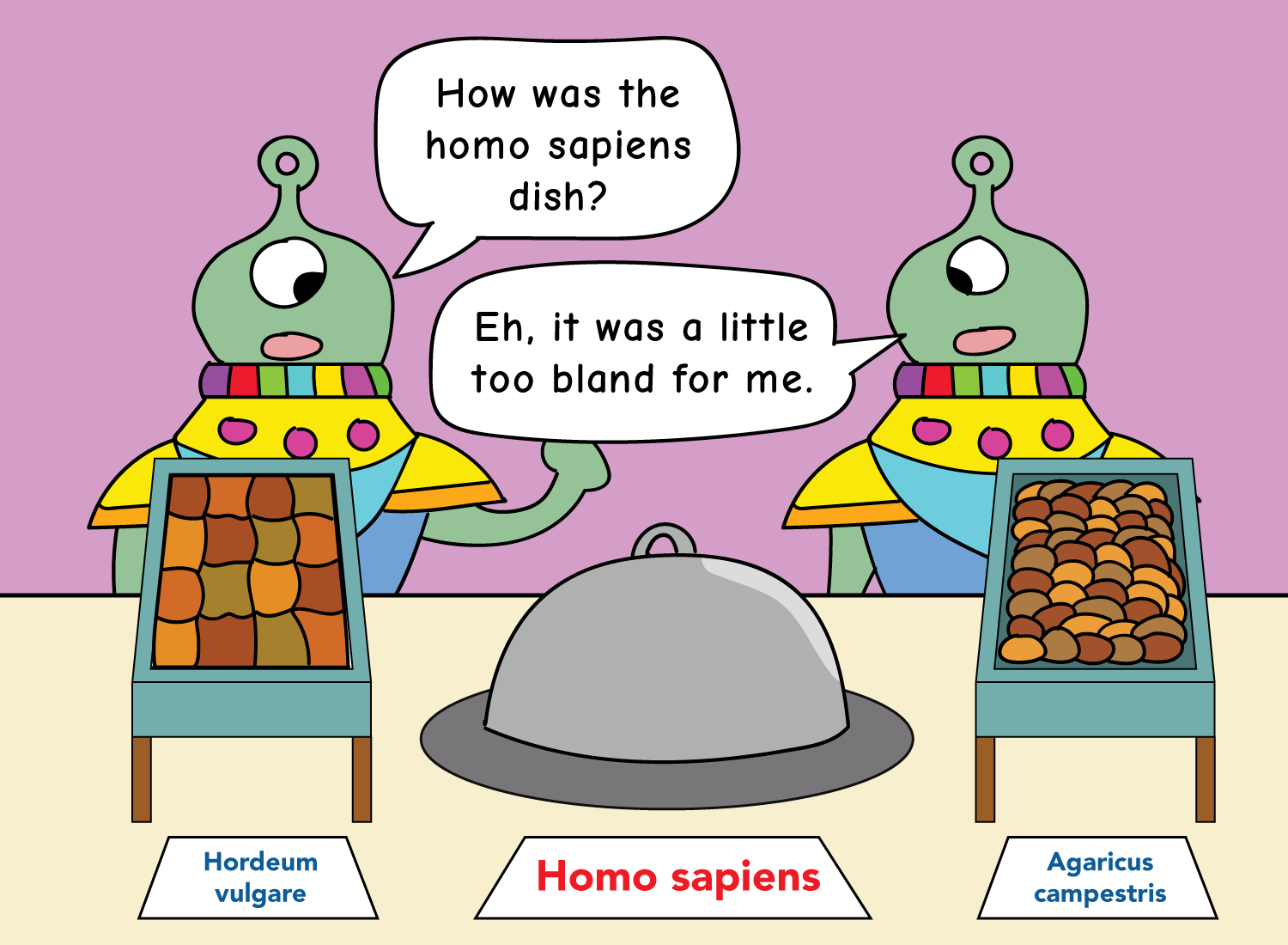

For example, let’s say we discovered that the true reason for our existence was to act as food for an intergalactic species that raised us specifically for our tasty meat. Homo sapiens was not the name for an intellectually advanced species, but more so the name of a moderately-priced delicacy on the buffet tables for these aliens.

Even if we discovered this truth, this wouldn’t satisfy our quest for meaning. We would undoubtedly ask what the fucking point was for our status as hors d’oeuvres, how we ended up in this predicament, and what the significance of the alien lifeforms were. The demand for answers in this world wouldn’t stop, and the absurdity continues. In fact, Nagel claims that the only way we derive meaning is when we simply choose to stop asking questions about it:

“What seems to us to confer meaning, justification, significance, does so in virtue of the fact that we need no more reasons after a certain point.”

I think this does a good job explaining why our views of the world tend to drift toward dogma and certainty. The meaning we derive from things stick because we’ve simply decided that we don’t need to pry any further, and that ultimately results in a “That’s just the way it is” justification at the bottom of all the reasoning.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a bad thing. Most of the time, things don’t need grandiose justifications; they simply are what they are. We don’t need an explanation for why we love our children, for why we want to lay down when we don’t feel well, for why we dedicate time to nurturing our hobbies. In fact, asking those questions takes away from the well-being they bring. And it is this very point that lies at the heart of what to do with the absurd.

It appears that the world doesn’t offer any inherent meaning to any one of us, despite our hopes for some easy answers. Just like a goat in the wilderness doesn’t go around strutting a sense of meaning, we too should not expect this inheritance from the universe, from God, from whatever we subscribe to.

While this view may seem depressing and nihilistic, I actually view it as immensely liberating and empowering.

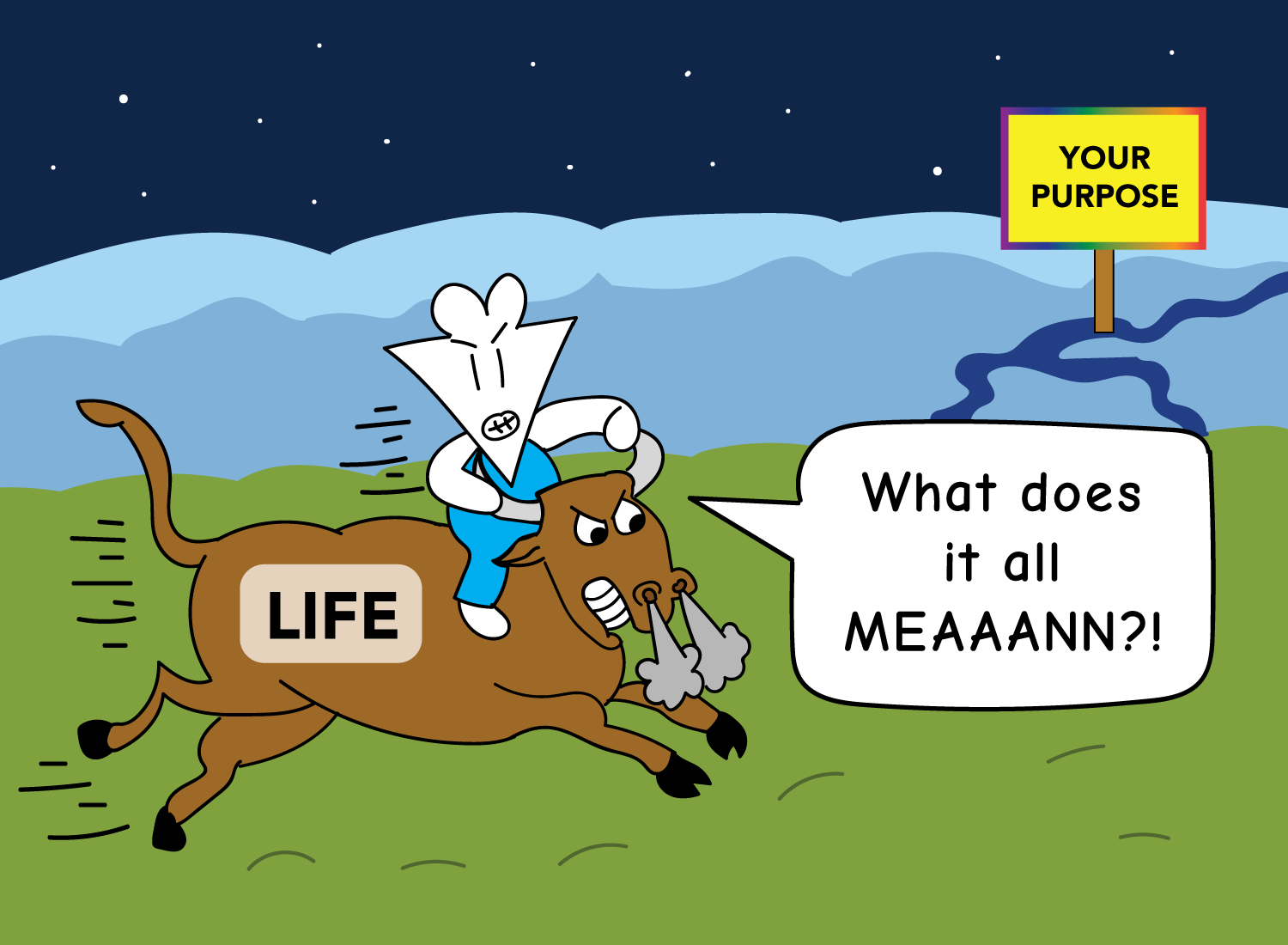

I find that the source of so much unhappiness in the world is our relentless hunger and quest for meaning. Society tells us to grab our life by the fucking horns, direct it toward the center of gravity known as “human purpose,” and do everything in our power to get there before we die.

In this futile pursuit of escaping the absurd, nothing will ever be good enough because we are always chasing an elusive grand narrative, our overarching meaning of life. We will forever be chasing our own tails, wondering when the hell the universe will answer our individual calls for purpose.

Ironically, knowing that life doesn’t come with a grander meaning allows us to access the things that really do make life meaningful. This truth helps us realize that the big existential questions of life are not where the answers are; instead, this very moment in our small corner of the world is all we really have.

Dan Harmon, the creator of Rick and Morty, summarizes it best:

We have this fleeting chance to participate in an illusion called ‘I love my girlfriend’ [and] ‘I love my dog.’ How is that not better?

Knowing the truth, which is that nothing matters, can actually save you in those moments. Once you get through that terrifying threshold of accepting that, then every place is the center of the universe, and every moment is the most important moment, and every thing is the meaning of life.

The questions of “What does it all mean?” and “What is my purpose?” are things we ask when we’re not plugged into this very moment. When we’re paying close attention to the project we’re working on, the book we’re enjoying, or the time we’re spending with our loved ones, then we’re not searching for meaning; we already have it.

Nagel concludes his paper by saying that “absurdity is one of the most human things about us: a manifestation of our most advanced and interesting characteristics.” So instead of being distraught by a lack of existential meaning, “we can approach our absurd lives with irony instead of heroism or despair.”

I like to think of this irony as the brief chuckle you let out when you’ve searched your entire home for your phone, only to realize that it’s been in your pocket the whole time. Similarly, we like to search for the meaning of life by looking over, beyond, and ahead of our existence, instead of realizing that it’s been there with us the whole time.

The thirst for more sounds comically absurd when you zoom out and see that nothing matters, so it’s about going deep into the zoomed-in life you already lead. Your health, your loved ones, your work, your interests, your desire to help others, your values, your existence.

What could be more meaningful than that?

_______________

_______________

Here are three other More To That posts that delve deeper into the jungle of our minds:

From Ignorance to Wisdom: A Framework for Knowledge

How Natural Selection Screwed Us

_______________

Sources

Thomas Nagel – The Absurd

Very Bad Wizards – Episode 126: The Absurd

Crash Course Video – Existentialism – Crash Course Philosophy #16

Dan Harmon – The Search for Meaning