The Riddle of the Well-Paying, Pointless Job

Work without pay is not a job, but work without motivation can certainly be one.

This distinction between money and motivation is glaring, yet most employers structure their organizations as if the two things are synonymous. Each step up the corporate ladder comes with an associated increase in pay, and our motives for working have led to a chicken-or-the-egg situation.

So what comes first: the desire for more money, or the desire to do better work?

We like to believe that the desire for self-improvement is innate, and that natural selection has sculpted us in a manner where betterment is the goal with everything we touch. Sadly, it doesn’t appear to be that way.

The desire to improve ourselves is not spread across the entirety of our lives. It’s mainly contained to a few areas that we want to actively pursue, sometimes to the detriment of other important areas in life. You can be an awesome employee in your company, but be an indifferent father once you get home. On the flip side, you can be a phenomenal father, but be an indifferent employee once you get in the office.

It’s the latter scenario that economists and psychologists have addressed over and over again over the last five decades or so. How can we transform an indifferent employee into a motivated one?

In 1976, economists Michael Jensen and William Meckling published a paper that seemed to definitively answer this question. In it, they concluded that executive pay must be directly tied to company performance – if the company did well, so would its leaders. This would result in an alignment of incentives, since the interests of the executives would match up with the interests of company shareholders.

This has come to be known as principal-agent theory (or incentives theory), and is the foundational structure that most corporations are built upon today. Pay people more, and motivation should follow naturally.

The problem with this theory, however, is that it failed to capture one major development in the landscape of work:

Jobs are becoming more and more pointless.

In his essay, “On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs”, anthropologist David Graeber articulates how this development happened:

But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning of not even so much of the ‘service’ sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations. And these numbers do not even reflect on all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or for that matter the whole host of ancillary industries (dog-washers, all-night pizza delivery) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones.

These are what I propose to call ‘bullshit jobs’.

If truly necessary and life-enhancing work were highly compensated, then Jensen and Meckling’s incentive theory may have worked. If teachers, garbage collectors, and construction workers were paid more, then the incentives may align properly, and you might see more motivated workers.

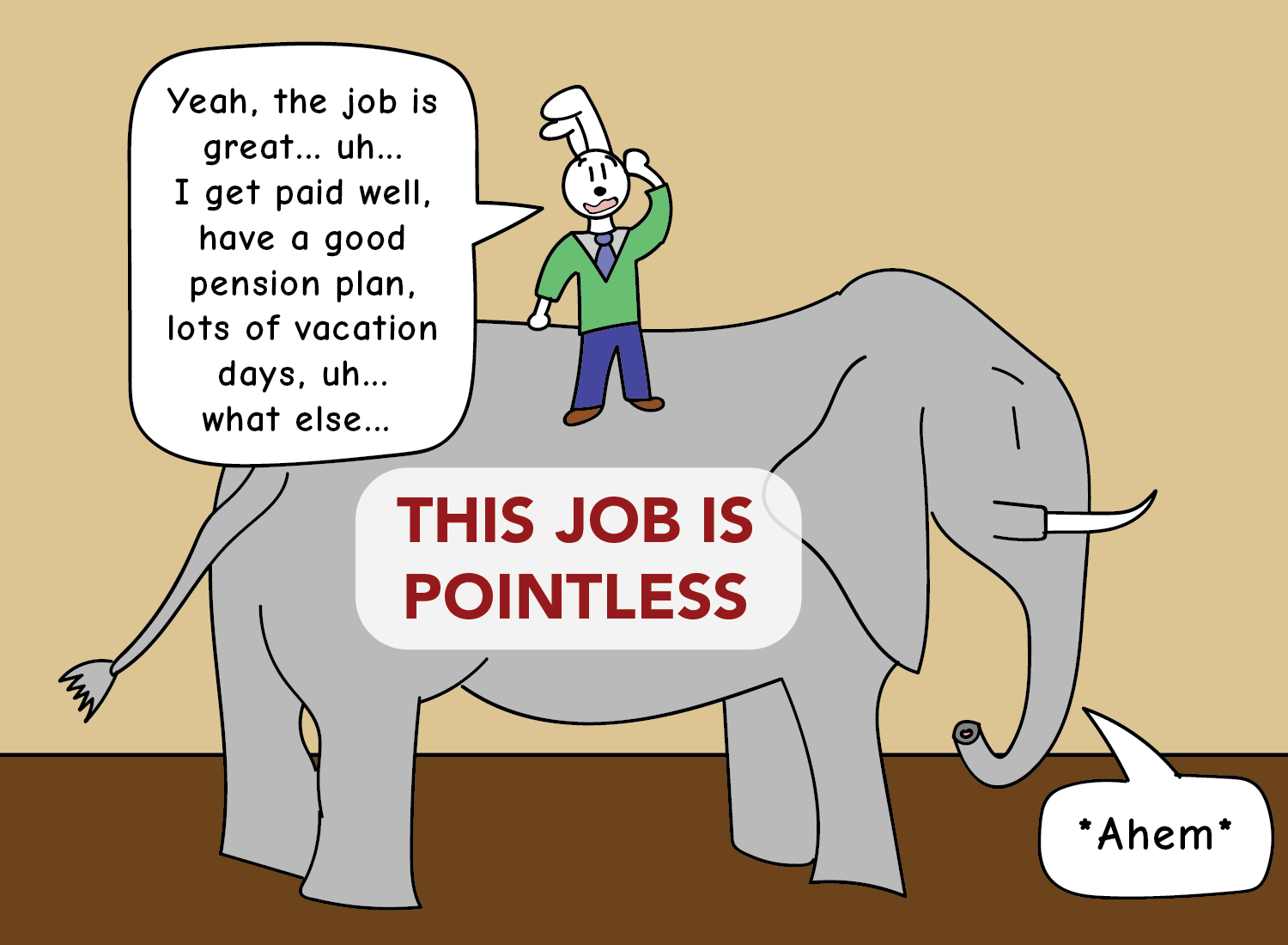

However, this incentive theory is being applied to spaces where the work is tedious, mind-numbing, and at best, manageable. Graeber calls these jobs “a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.”

These are the jobs where you know you could do the work in 1-2 hours each day, yet you have to pretend you’re working for a whole 8-9 hours. You know this, your boss knows this, your boss’ boss knows this.

Everyone is aware of this fact, but here’s the most malicious part: everyone has to pretend they don’t. A company-wide charade is being played, with everyone pretending that not only are they busy and driven, but that everyone else is too.

This is the era of the pointless job, and if you’re fortunate enough to have a job that’s meaningful, then I’m sure you won’t have to look too far to find someone who doesn’t. The irony though is that this person might say that their working conditions are pretty excellent – they have great health benefits, a nice pension plan, a really nice office, and so on.

The only problem is that their job seems utterly… pointless.

If money is the only reason you’re working somewhere, then good pay is the only rational justification for your continued employment. This, however, doesn’t mean that the incentive theory works. This only means that money makes your job more manageable, not any more motivating.

But what about the opposite? What about people that are motivated with their work, but don’t make a lot of money?

Clayton Christensen, Harvard professor and author of How Will You Measure Your Life?, touches on this side of the coin:

So if money isn’t motivating them, then what is?

This is a good time to introduce Frederick Herzberg, a psychologist that published a popular Harvard Business Review article in 1968. It’s titled “One More Time, How Do You Motivate Employees?”, and it introduced a different approach to workplace motivation.

In what is now known as two-factor theory (or motivation theory), this approach distinguishes between two factors that are essential for workplace motivation: hygiene factors and motivation factors.

Let’s frame workplace satisfaction in the form of a cup:

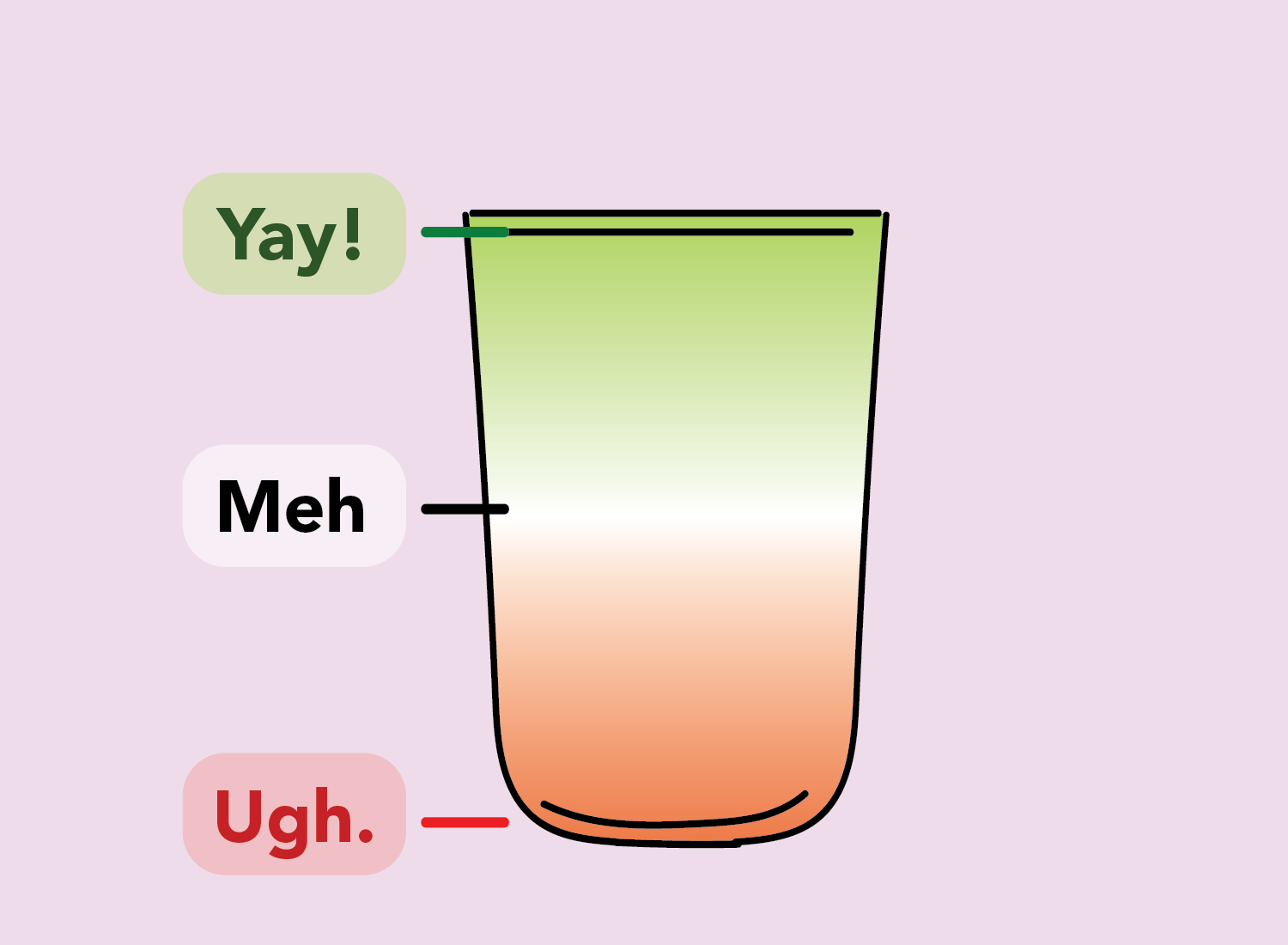

The baseline level of job satisfaction is indicated by the middle point in the cup – if you’re at that point, you’re just “meh” with your gig. If you’re above it, you’re digging your job. If you’re below it, things suck.

Let’s fill the cup up to the baseline point with some water.

The hygiene factors are elements where, if they are missing, they will lead to job dissatisfaction. These factors take a “glass half-empty” (subtractive) perspective, and can only decrease the amount of water in there.

Hygiene factors are things like compensation, job security, work conditions, relationships with colleagues, supervisory practices, and company policies. If you decrease the quality of any of these factors, then that will cause you to be dissatisfied. For example, if you find out that your boss is a neurotic, micromanaging maniac, the hygiene factor of “supervisory relationship” will be missing, and you will be dissatisfied.

Notice above that compensation was included as a hygiene factor, and not a motivator. This distinction is important.

Since hygiene factors don’t have the ability to increase your job satisfaction (they are merely subtractive in nature), a bump in your pay won’t do much. As Christensen puts it, “if you instantly improve the hygiene factors of your job, you’re not going to suddenly love it. At best, you just won’t hate it anymore. The opposite of job dissatisfaction isn’t job satisfaction, but rather an absence of job dissatisfaction.”

Sufficient pay can’t increase the water level of the cup, but insufficient pay will certainly decrease it. This is the nature of a hygiene factor. Even good workplace relationships alone cannot bring you job satisfaction; the best they could do is keep you at the baseline level.

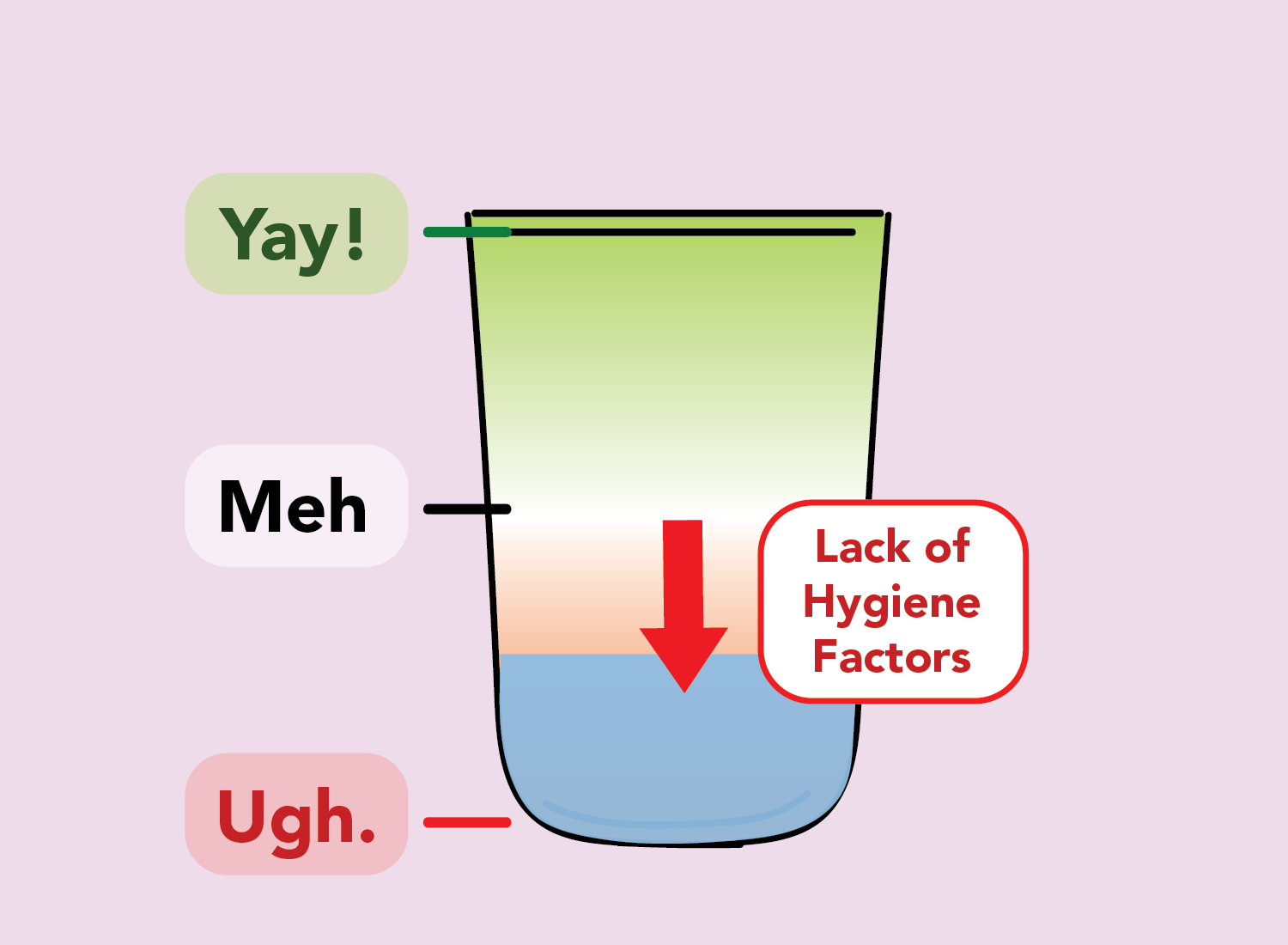

So what can actually raise the level of the water? Well, that would be the second factor of Herzberg’s theory: motivators.

Here’s Christensen’s definition of motivational factors:

These motivators are the only things that can push the level of water upward into the territory of job satisfaction. While it’s important to feel financially stable and work for a company with values you agree with, it is only through challenging and engaging work that can make you really love going there.

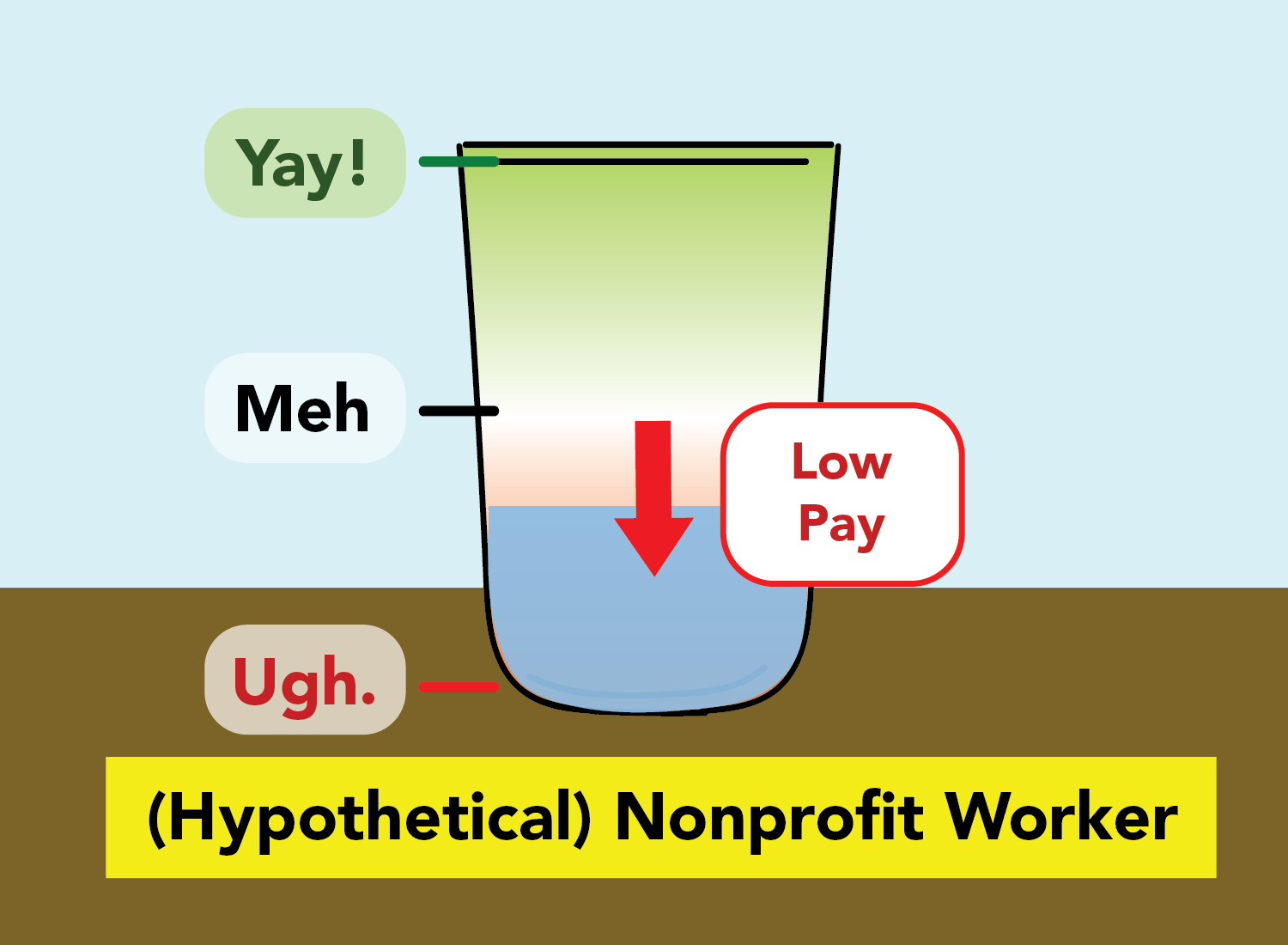

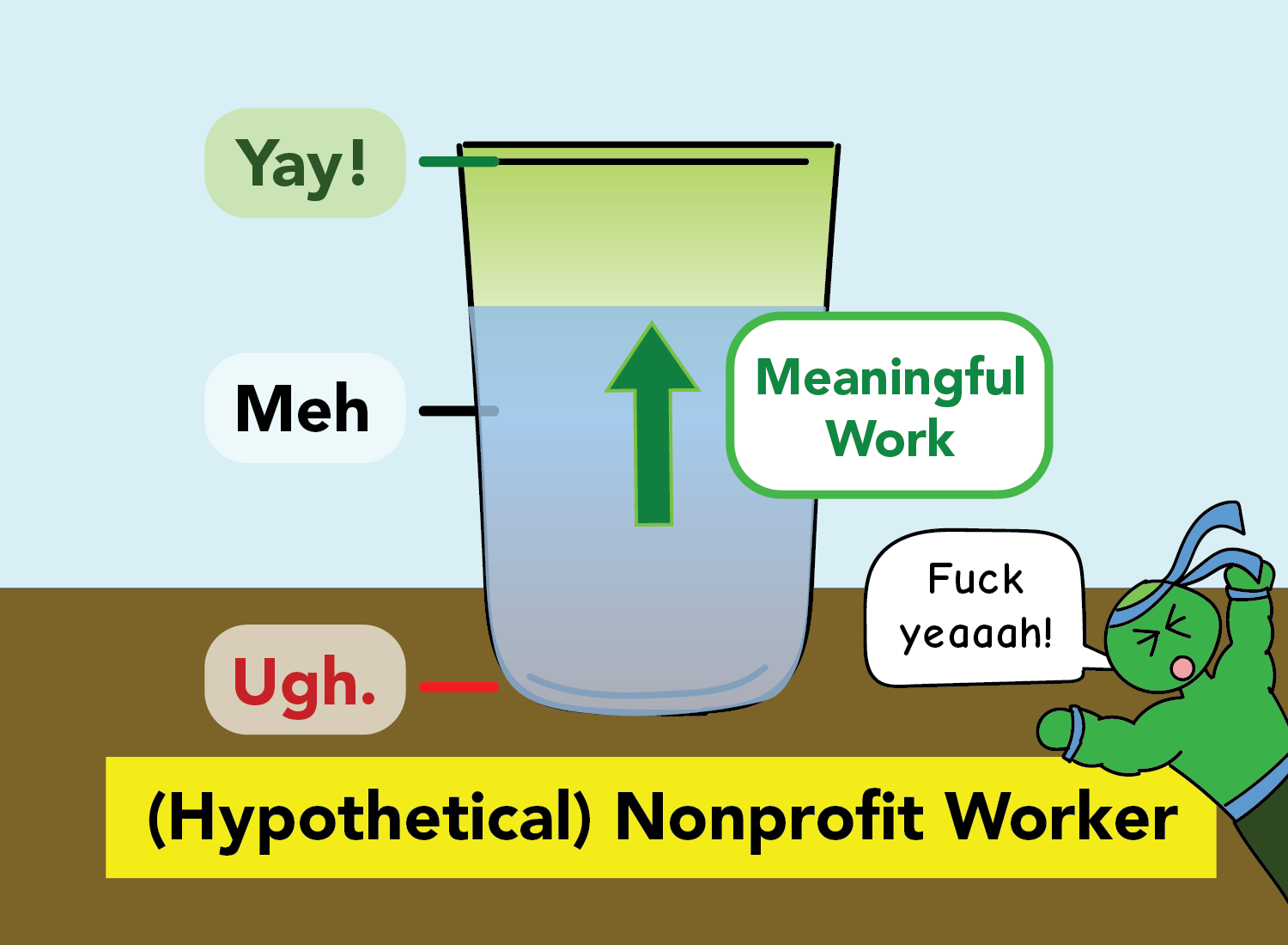

In the case of the nonprofit worker that Christensen described earlier, his pay might be lower than he wanted, leading to some dissatisfaction (hygiene factor):

But the meaning that he was getting from his work allowed for an increase in satisfaction due to the additive nature of motivators:

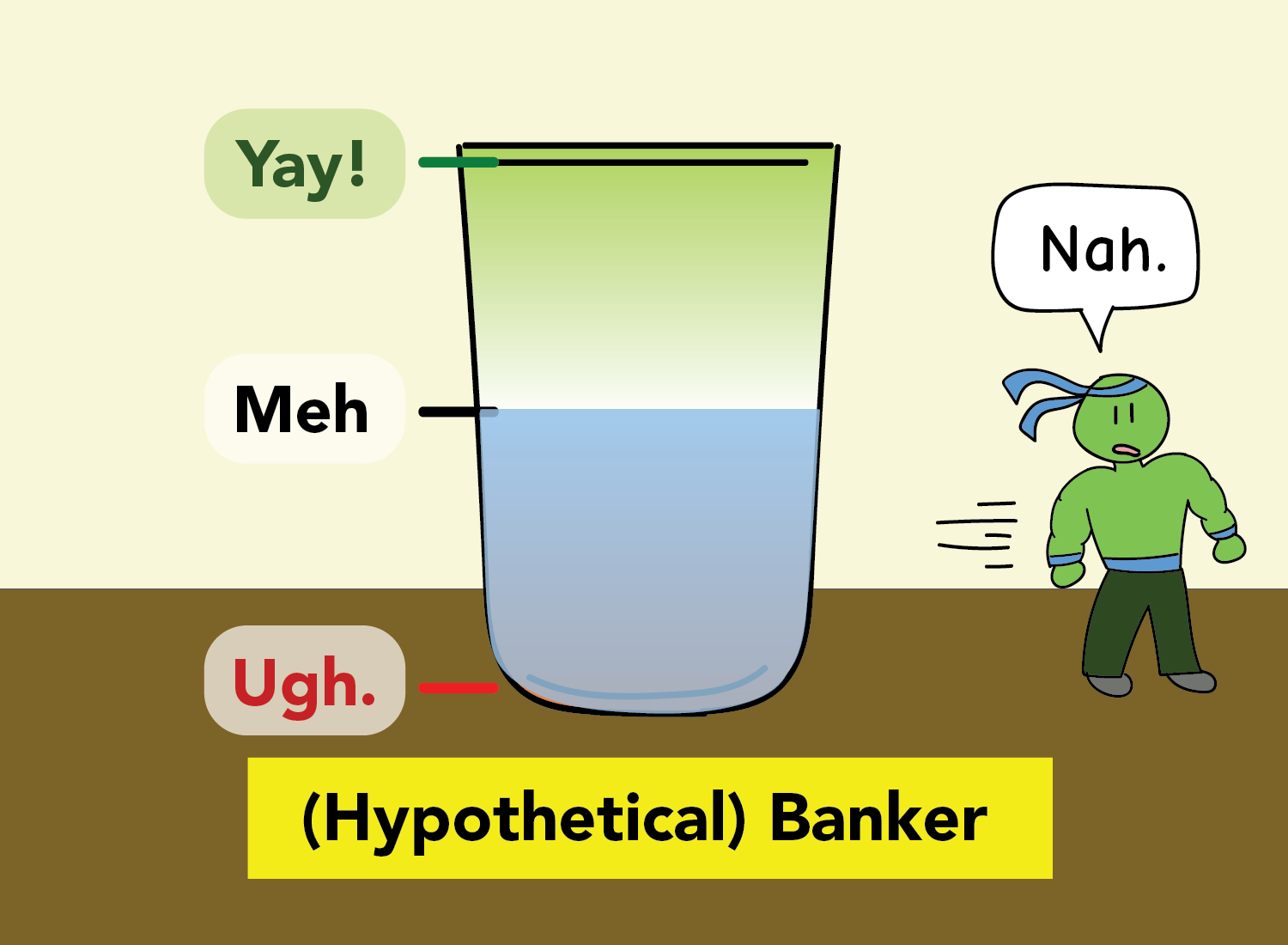

In the case of a hypothetical banker with a pointless yet high-paying job, her hygiene factor of compensation is intact, leaving her water untouched:

But the meaninglessness of the job is preventing any motivational factor from increasing her overall satisfaction with it:

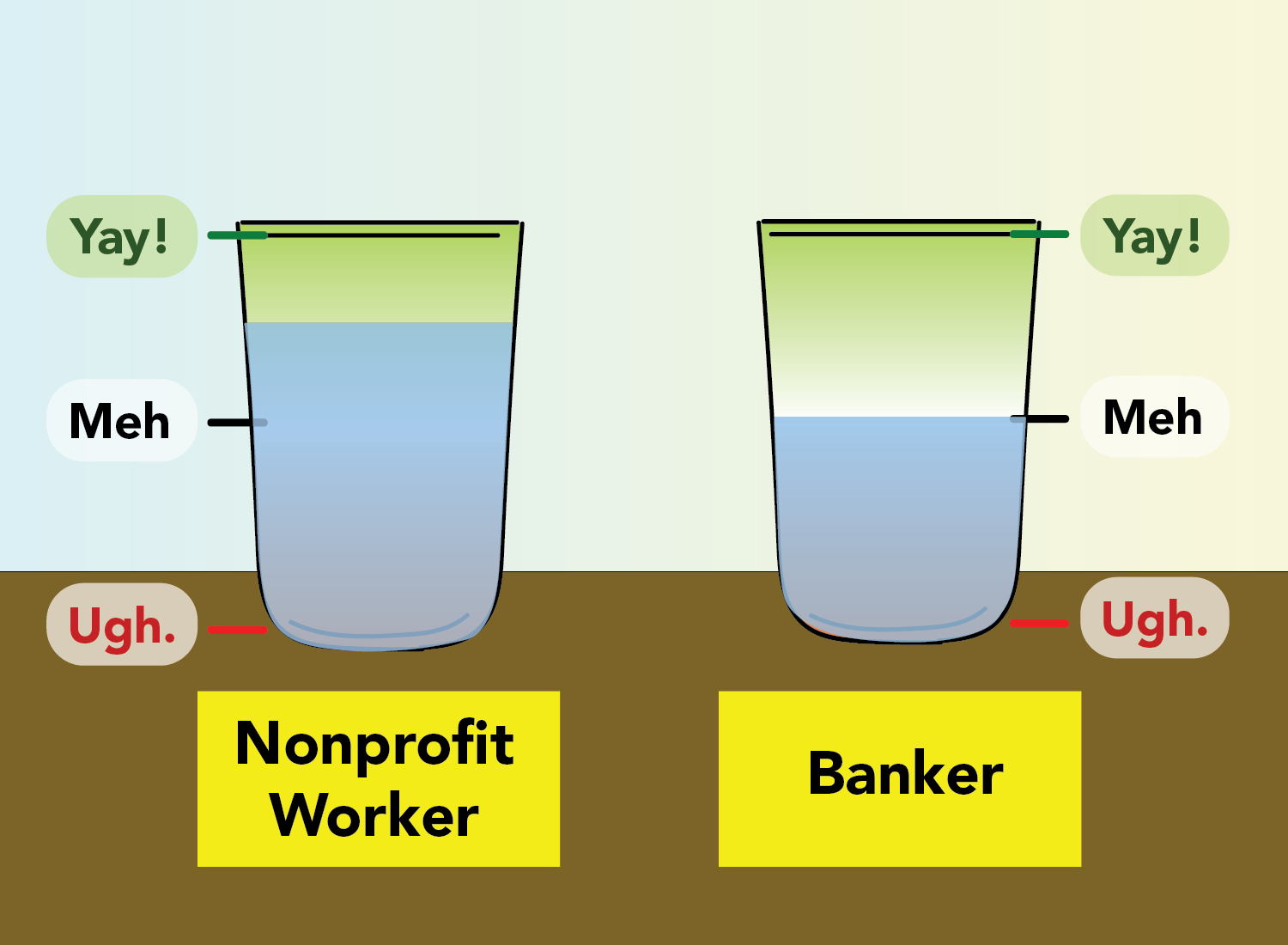

This results in an interesting situation where the lesser-paid nonprofit worker is more satisfied with his job than the higher-paid banker:

When you see an illustration like that, it’s easy to assume that the lesson here is to quit your pointless job and do something that motivates you. Well, if you’ve made that assumption, I’m going to one-up your assumption and assume that you’ve already forgotten that there are two things we need for job satisfaction:

(1) Keep hygiene factors at the baseline level, and

(2) Increase motivational factors.

If you suddenly quit your job, you’ve essentially obliterated the first part. You’ve removed a whole bunch of hygiene factors you previously had, which included compensation and financial security. So unless you have the proper systems set up to go full-time into your next thing, this isn’t an advisable move.

Instead, I want to add something to the equation that I feel is pretty important. So far we’ve been looking at your occupation in the form of a singular cup, which symbolizes your current level of job satisfaction. While this cup is a good gauge for how much you like/dislike your job, this may not paint the full picture of your work life in its entirety.

The reality is that a bigger cup exists, and this one measures your overall work satisfaction.

This larger cup represents the summation of all the other cups you may have in addition to your day job: the e-commerce business you’re building on the side, the blog you’re spending your nights working on, that album you’ve been creating on the weekends. This represents how satisfied you are with all things work-related, and indicates how you’re feeling about all the effort you’re putting in during your waking hours.

This is why a side hustle is so important if you have a pointless job (and if you want work to be a source of meaning in life). Since there are no motivating factors present at your day job, you must get those from somewhere else. Perhaps the hygiene factors aren’t quite there for the side hustle (it might not be making money, things feel a bit lonely, etc.), but if the motivators are present, then that can make you feel good about what you’re doing.

The key is to have the water level of the overall work satisfaction cup above the baseline as much as possible. If you have a pointless day job that pays the bills, take advantage of your financial security and spend your available time working on the things that truly motivate you. The net effect of these cups is what really matters, and with enough effort and intention, you just might be able to transition full-time to the work that you find meaningful.

If a side hustle doesn’t sound like the solution, then either it’s time to find another job, or it’s time to find ways to make your current job more motivating. This is something that goes beyond the scope of this post, but I’m sure it will involve some combination of deep, inner soul-searching and a bunch of difficult, daunting, yet necessary conversations with your team.

Given the current landscape of jobs, it’s clear that the money-drives-motivation theory needs updating. We will spend about a third of our lives working, and for something that significant, we should be guided by a belief system that maps onto what’s possible.

As you think about your career path, remember that the absence of job dissatisfaction is a low bar to settle for. However, also keep in mind that no amount of motivation can substitute the necessity of hard work.

The key is to find something that you’re willing to go deep into, and to stay there for a long, long time.

_______________

_______________

For more posts about work challenges:

Thankfully, Life Is Full of Problems

The Creator and the Crowd: Originality’s Balancing Act

For a post specifically about writing-related work:

The Economics of Writing (And Why Now Is the Best Time to Do It)