When 1 + 1 = 3

In the 4th century BCE, word got around of a hip new school that opened in Athens. It was started by a guy named Plato, and he was teaching philosophy to anyone that wanted to learn about the nature of reality.

This school was known as the Academy, and its influence stretched far beyond the lifetime of its founder. It produced some of the brightest minds of the ancient world, some of which included Aristotle, Heraclides, and Xenocrates. Many students from all around Greece came to study at the Academy, and when each one passed through the front gates, they were greeted by this sign:

There was a reason Plato held math in such high esteem, and it had everything to do with his belief in the world of Forms.

He famously taught that everything we saw in the world were distorted versions of perfect ideals, which he called Forms. Since the lens of human perception is limited by design, whatever we interact with are shittier versions of the true, godlike version that lives in a separate realm.

For example, let’s say we come across this squirrel as we’re moving about our day:

We will confidently assert that this is a squirrel, but Plato would say that this is just a low-resolution version of the real thing, which is a fucking majestic squirrel that is perfect in every way possible.

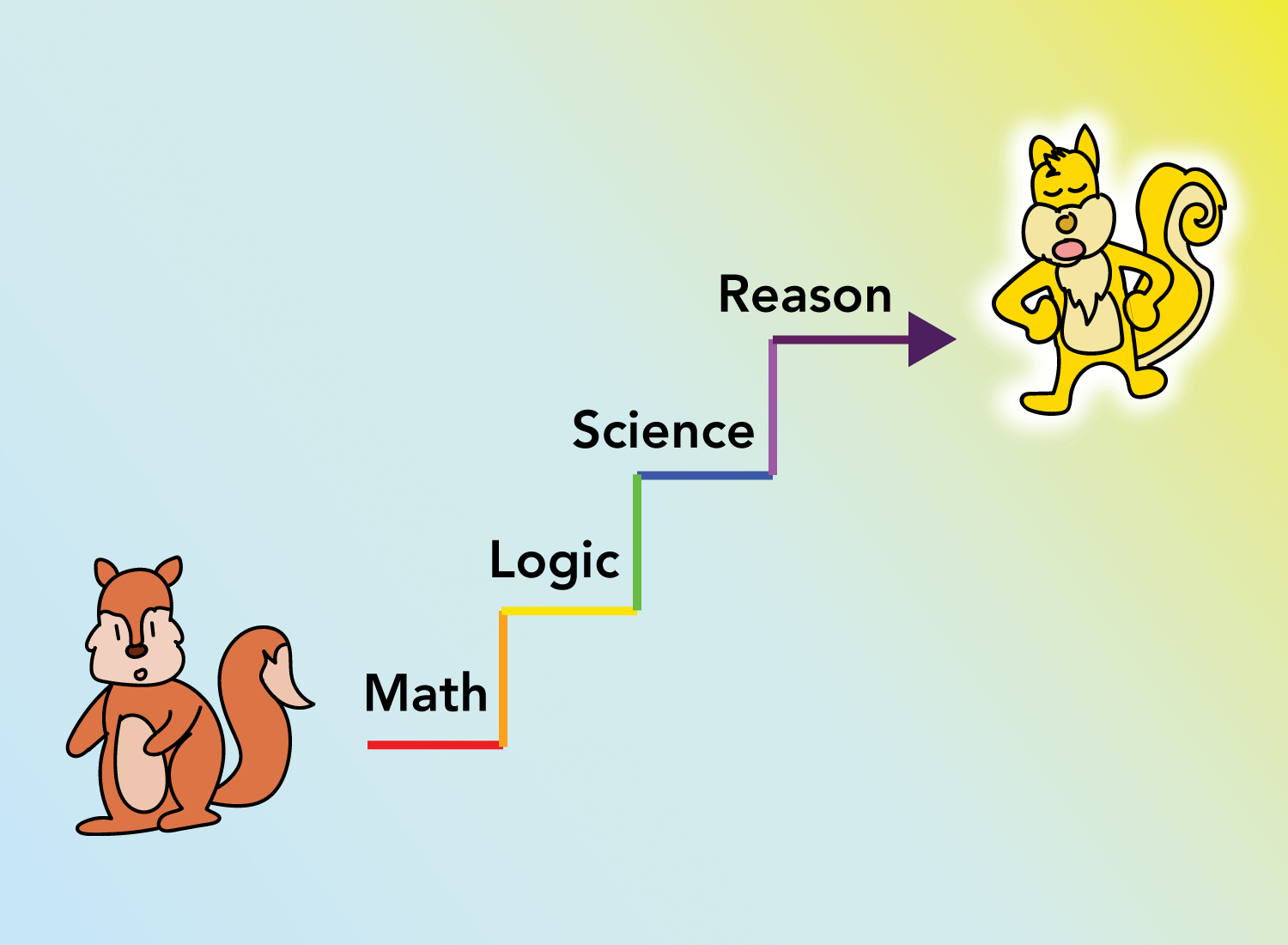

The only way to access this God Squirrel and every other ideal that lives in its world is through one thing: reason.

Plato claimed that our senses led us astray, leading us to make erroneous conclusions about the structure of reality. Instead, he wanted people to reason their way to the truth, using math, logic, and science to measure and determine the laws that govern the world of Forms.

Through this theory, Plato unwittingly laid down the foundations for rationalism, which would go on to champion the usage of science and math to reveal the truth. Rationalism’s fundamental assumption is that our senses cannot be trusted, and that a commitment to reason will translate into a better informed society. Not only will we see the truth, that truth will help us become wiser people as well.

But here’s the thing: How would discovering mathematical and scientific truths translate into collective wisdom? If we uncovered everything we needed to know about the nature of reality, would that lead to a more informed society that makes better decisions?

My answer to that second question would be a fervent “no.” Rationality’s error is in assuming that rational conclusions create rational people. That if reason revealed an objective truth, everyone would champion that truth because it is undeniable.

The thing we often forget is that humans value freedom over truth. We want to choose what we believe in, even if we know that the belief itself is bullshit. In other words, the accuracy of the belief matters less than the agency we exercised to regard it as our own.

For example, let’s take a truth that (most) people wouldn’t deny.

We live in a cosmos where 1 + 1 = 2. The nature of reality is structured in a way where adding one atom to another makes two, and that is a fundamental axiom that constructs our material world. If 1 + 1 didn’t equal 2, let’s just say that the world as we know it would be replaced by something utterly unrecognizable.

But despite this universal truth, there are people who would rather assert that 1 + 1 = 3. In fact, doing a quick search for that equation will yield a number of videos and forum posts that rationalize that conclusion. Most appear to be doing it in jest (or to simply be a contrarian), while others attempt to seriously break it down to validate their position.

This is a small reminder that even fundamental axioms cannot withstand our desire to come to our own conclusions. If even 1 + 1 = 2 is questionable for some, how can we expect reason to unite us? If we used the scientific method to uncover all the truths about reality, how would that solve our desire to believe whatever the hell we wanted?

Humans have a natural tendency to balk at determinism. We don’t want to be told that our lives have to be lived according to a certain plan, and that our decisions are constrained by preset formulas and laws. Even if we know that we live in a world where 1 + 1 = 2, we would find it deeply compelling to live as if 1 + 1 = 3.

This explains why we make decisions that elude all rationality, just to prove to ourselves that we can. Or why things happen in the world that don’t make sense, but keep happening anyway.

Stock prices don’t increase ten-fold in ten days because of a careful analysis of historical cash flows. No, that happens when retail investors corral around an ailing company as an unexpected bastion of hope.

World wars aren’t the result of a logical sequence of events that follow a predictable pattern. No, they start with the assassination of a little-known duke from a country with little power.

Tyrannical leaders aren’t elected because they say sensible things that elevate the country as a whole. No, they seize upon a weakness in the system, and stoke an irrational fervor to create an Us versus Them dynamic.

Rationality presumes that the truth is all-powerful, but it misses one crucial point: Truth is powerful only when it is coupled with agency. It’s not enough to be told by a reliable authority that an objective fact has been discovered. If people felt like they had no hand in unearthing that truth, they will do everything in their power to believe its opposite.

Conspiracy theories are enticing for this very reason. Their allure doesn’t stem from the content of the belief, but from the personal freedom one exercises to advertise it as theirs. It’s a classic example of people saying “fuck you” to the reality of 1 + 1 equaling 2, and deciding that they’d rather live in a world of their own choosing.

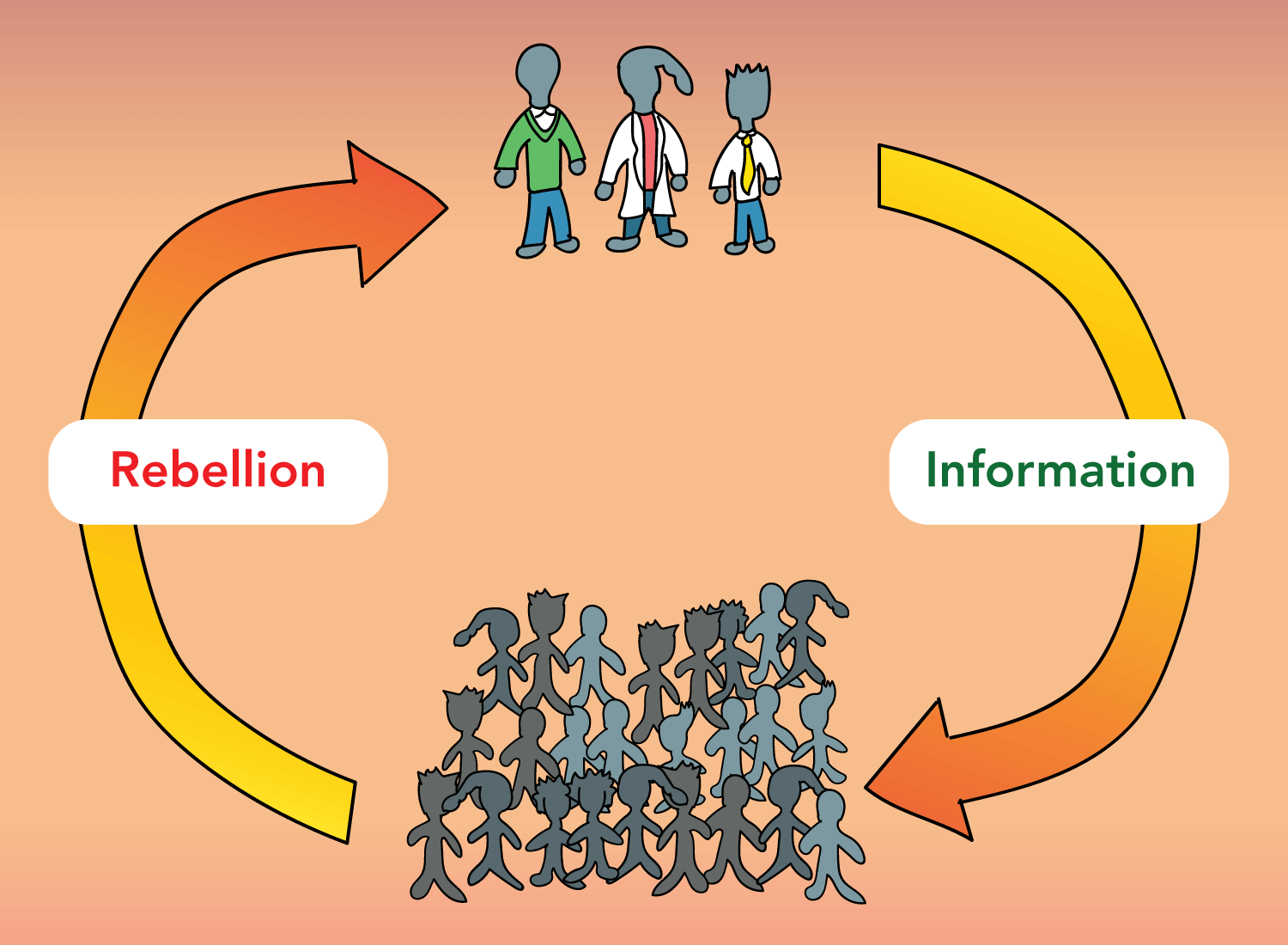

This is why scientific progress will not unify humanity (even if we desperately want it to). There will always be an asymmetry in the handful of scientists pushing the boundaries of what we know, and the mass of people that have to decide what to do with those findings. And given this asymmetry, many will choose to rebel against the “intellectual elite” for the sheer purpose of exercising their freedom. As long as discoveries are communicated in this fashion, this dynamic will continue to exist.

What this reveals is that the messaging of the truth is just as important as its discovery. If you deliver the truth as if your dissenters are ignorant or stupid, then it won’t matter how accurate your views are. People listen only when good faith is presumed. Rational conclusions only work if they are delivered with empathy, and only then will people be willing to dig deeper into what you are proposing.

Of course, this is hard in any polarized climate. When the size of an echo chamber expands, so does the arrogance of its constituents, and the capacity for compassion contracts. But keep in mind that the disbelief you may feel about the other tribe’s position is exactly the same way they feel about yours. The way you shake your head at their assertion of “1 + 1 = 3” is exactly what they’re doing when you state your beliefs as well.

In this scenario, the only way to make 1 + 1 = 2 a compelling idea is not to provide a mathematical proof, but to be irrationally compassionate. Perhaps even foolishly so. By being the kind of person the other might want to be. By listening when you don’t want to. By attempting to understand when you’d rather not.

Because in a world where 1 + 1 = 3, sometimes the most irrational move is the right one to make.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

When 1 + 1 = 3 is adopted at a large scale, danger ensues:

The Power of the Dissenting Voice

Here’s the model I use to test my own rational faculties:

The Information Lifecycle: How Three Filters Shape the Mind

Spirituality often plays at the border of rationality and imagination: