Words Are the Sculptors of Culture

Words are weird.

On one hand, we use them everyday and fail to see anything special. We write them down, make mouth noises with them, and even think them without the slightest hint of amazement.

On the other hand, we recognize how even the smallest changes in word choices affect us in a big way. We understand that words hold immense power, and are able to shape the way we think or feel about the world we live in today.

In 1974, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus conducted a simple experiment that showed just how easily words sway our perceptions.

First, participants were shown films clips of various traffic accidents:

Then they were asked about what they had seen.

Like I said, super simple experiment, but what Loftus learned was super interesting.

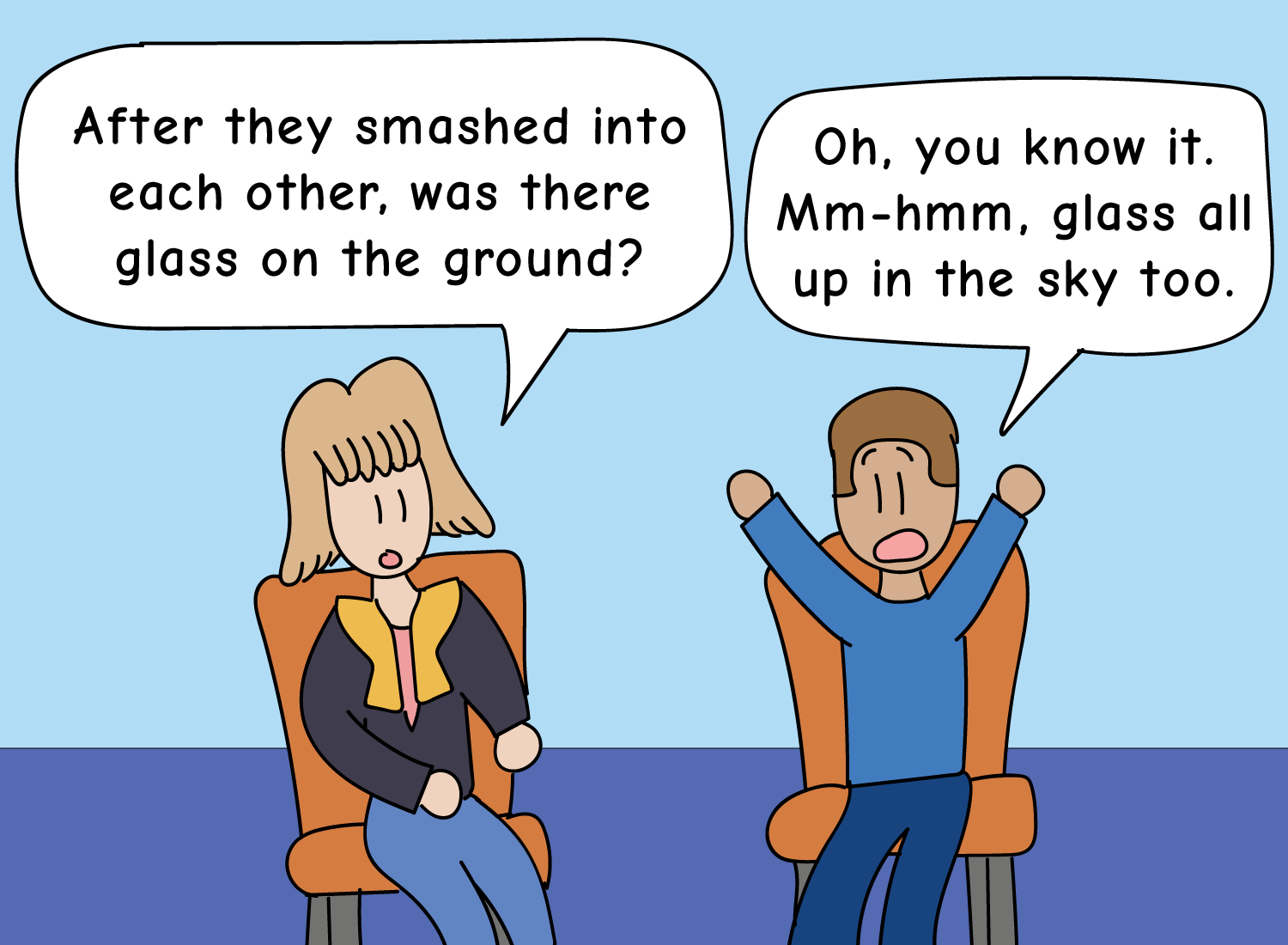

Loftus found that the way she phrased her questions had a significant influence on how the participants reported the accidents. For example, when she asked them to estimate the speed of the cars, their answers varied widely depending on whether she used the words “bumped,” “collided,” or “smashed” to describe the event. She also asked them to recall if there was broken glass after the collision, and the answers again depended on the wording she used to describe the speed of the vehicles.

Loftus keenly observed that these faulty recollections were most applicable to the field of law, where eyewitness testimonies could be distorted by suggestions and leading questions. Lawyers could easily plant misinformation into eyewitnesses through slight phrasing cues, and the subtlety of this is what made it so pernicious. She went on to say that “the unreliability of eyewitness identification evidence poses one of the most serious problems in the administration of criminal justice and civil litigation.”

Loftus understood how words affect the recollection of events, and how that can then go on to shape the direction of an individual’s life. Something as inconsequential as substituting one word for another can change the texture of a memory, and perhaps even its contents.

This leads to a question I’ve been thinking about lately:

If word choice can have such a dramatic effect on the individual, what can it do when scaled up to the level of culture?

The way a culture forms is based on a vast array of factors, but its shared language is perhaps its greatest sculptor. The manner in which people communicate is what determines a culture’s principles, its sense of morality, and its incentive structures. Words aren’t merely words; they are what shape the behaviors of everyone that uses them.

I recently watched an episode of Parts Unknown, where the late Anthony Bourdain took a trip to the country of Senegal. Senegal is one of the few African nations that never had a coup d’état, and its citizens enjoy a high degree of religious freedom. There was no bloody transition of power when it gained its independence from France in 1960, and the country has been largely free from any civil wars or ethnic conflicts since then.1

When asked about the relative peace and stability within the country, the Senegalese would often refer to a single word that defines the culture: teranga. Crucially, this word doesn’t have a suitable English counterpart. In a broad sense, it may be translated as “hospitality,” but that doesn’t seem to get anywhere close to the true essence of the word. To get closer to an actual translation, you would have to use a beautifully constructed sentence, as one of the people did in the episode. He described it as such:

The most important value is what we call teranga: The more you share, the more your bowl will be plentiful.

Teranga.

By giving this sentiment an identifiable word, it has the ability to spread across the collective consciousness of the Senegalese people. By compressing a complex emotion into a short series of letters, people can point to it the moment it is felt, and a mass awareness ensues.

How much of Senegal’s relative stability can be tied to this awareness of teranga? That everyone in Senegal not only knows what it is, but has likely felt it in a visceral way? And that they can reference it the moment they feel it between one another?

Culture is shaped by identifying and naming the unique dynamics that exist between its people. Through this process, you get an understanding of the feelings and values that are specific to that culture, and those that only exist within its bounds.

To give a personal example, there’s a Korean word called jeong that has no adequate English counterpart either. Some people describe it as “love,” but that’s a very low-resolution description of it. It’s an incredibly nuanced word, and my best attempt to explain it would be something like:

“An all-encompassing warmth you feel when coming into contact with someone familiar, regardless of whether you have met them before.”

And even that doesn’t do it justice.

Jeong is another example of a culture identifying an incredibly complicated emotion, and making it accessible to all its people. Koreans often refer to it as the reason why they feel an immediate connection to other Koreans they meet abroad, leading to tight-knit communities that flourish over time. It also applies to familial bonds, strangers, and even to animals as well. It’s a unique feeling that has translated into an over-arching value for the Korean people, which has been instrumental in shaping the country into what it is today.

If your cultural background extends beyond that of an English-speaking one, you’ll likely know of a specific word that can’t be adequately translated either. And chances are, that word will have immense importance over how your culture moves and operates. This is no coincidence.

Words are the sculptors of culture. They are the invisible forces that differentiate one set of perspectives from one another, and allow them to take on an identifiable form. That’s why every culture has a few words that are widely understood among its people, but may be deemed wholly unique to them.

An important thing to remember is that America, the country I reside in, also follows this same pattern.

The one word that seems to define American culture is “freedom.” It’s a concept that has been firmly entrenched as a value, and no one in the country would find it dispensable. However, in the same way that teranga or jeong cannot be sufficiently translated into English, I’m realizing that “freedom” may not have an adequate counterpart in any other language as well. Of course, a solid dictionary translation of the word will exist everywhere, but it won’t capture the way it’s been uniquely internalized within American culture.

The American encapsulation of freedom has allowed it to become a powerhouse of diversity, commerce, and creativity. The widespread understanding that you are free to make your own choices (as long as it’s within legal bounds) has attracted incredible talent from all across the globe, creating one of the most differentiated cultures the world has ever seen.

But at the same time, this unique view of “freedom” has also made unified decisions incredibly difficult, which is evidenced by the complete failure of the country to contain the pandemic. People from around the world were utterly perplexed as to how millions of Americans continued to be so careless as case counts and deaths skyrocketed. But as an American, it’s just not that surprising.

“Freedom” has sculpted the culture in a way that no other value can supersede it – even when it comes to matters of one’s health. Your right to do what you want to do cannot be threatened, even in the midst of a global crisis. And perhaps that is something that other cultures simply cannot wrap their heads around.

If the texture of the word “freedom” were similar across all cultures, then we’d likely see uniform responses to global issues. If jeong or teranga were truly synonymous with “love” or “hospitality,” then we wouldn’t wonder if nuances need to be explored within those words.

But the beauty of culture is that no two are the same. And this is because certain cultures have identified emotions that others have not.

Teranga was felt across many generations before the word “teranga” was ever uttered. But the fact that it was named is what uniquely sculpted Senegalese culture. By putting a name to an abstract feeling, that abstraction becomes real, and it has the power to become a value.

Words sculpt culture, which in turn shape the individual. When you keep this in mind, you’ll realize that by naming what we feel, we build the reality that we occupy.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Sometimes our words need to be directed against culture, not for it:

The Power of the Dissenting Voice

How writing converts your words into the Trophies of the Mind:

Write for Yourself, and Wisdom Will Follow

And don’t forget that the absence of words is a form of speech as well: