True Learning Is Done With Agency

People often ask me what I studied in college. And given the nature of topics I write about, most assume that I studied philosophy or psychology. After all, I’m fascinated by how the mind works, and am curious about how a gathering of these minds add texture to the human condition.

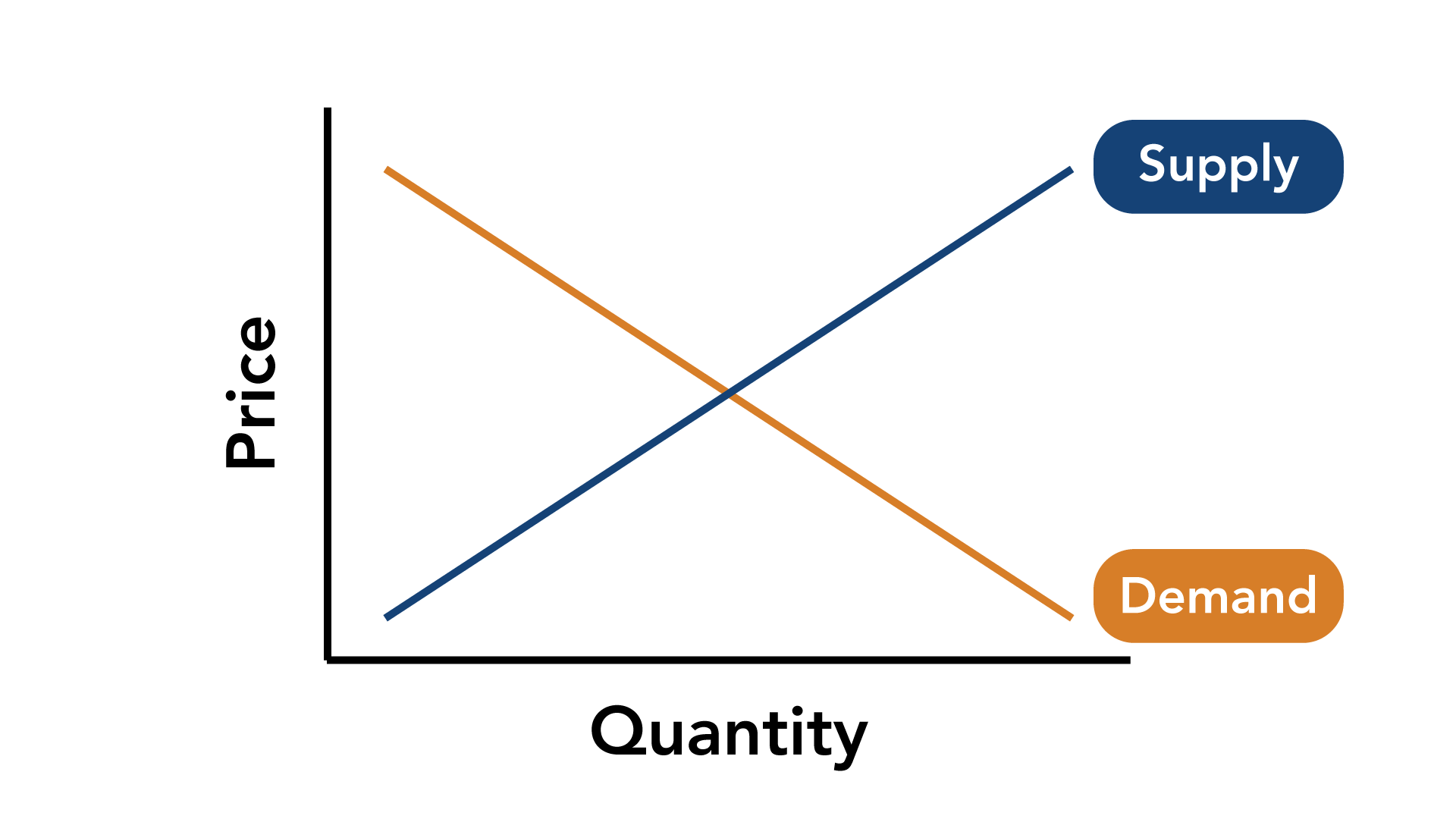

Well, the actual answer is economics. And if you were to ask me what my biggest takeaway from my collegiate education was, it’d look something like this:

Ah, the good ol’ supply and demand curve. Something I learned in high school was still the most memorable thing to me after 4 years of college.

In other words, I didn’t learn very much.

But to be clear here, this says more about me than it does my teachers. Many of my professors were probably great, but my indifference toward the subject prevented me from seeing just how great they actually were. It was my lack of demand for knowledge that made my education suffer, and not because of a shortage of supply in good teachers.

Like many people, I chose my major because I didn’t know what else to do. And when you’re faced with this uncertainty, the path forward is one of practicality. You choose something that ensures predictable pathways, from well-trodden careers to greater levels of education. I knew that with an economics degree, I could get a finance gig somewhere, and if all else failed, I could leverage that to pursue a master’s or something of that sort.

Of course, with rationale like that, it’s unsurprising to hear that my heart just wasn’t in it.

One of the great problems with the collegiate educational system is that it incentivizes practicality over curiosity. There’s a well-constructed funnel that shuffles students from:

(1) A field of study, to

(2) An emphasis on specific pieces of knowledge, to

(3) Career fairs, to

(4) A job.

Everyone goes to college knowing that the end goal is to walk away with a job that is well-adapted for what they studied over the last 4 years. Or if you’re in a more specialized field like medicine, that the goal is to attend a prestigious program that will give you the skills required to finally have that job you wanted (doctor, nurse, pharmacist, etc.).

Regardless of the path you take, you go on it with the knowledge of the end in mind. And the more certain you can be of what that end looks like, the more likely you are to pursue it. After all, most of us are conditioned in our youth to avoid risk, so it’s no surprise that the paths containing the most footprints are the ones that look the most reasonable.

But the cost of structuring your future in this way is massive.

First off, I operate under the belief that curiosity is a fundamental component of consciousness. Some may balk at that statement, but it’s becoming increasingly clear to me that this is true.

The reason why millions of people are so dissatisfied with their work despite their high pay or accolades is because no fiscal incentive or reputational reward can replace the dimmed light bulb of one’s curiosity. If the things you work on don’t give you the freedom to roam your own mind according to your interests, then time will be your enemy. You might be able to rationalize your predicament for a few years, but attempting to do so for decades will introduce an identity crisis that you won’t be equipped to handle.

The second is perhaps the more important of the two, and it has to do with agency.

The reason why people think I studied philosophy or psychology in college is because I seem to know a decent amount about it. But in reality, the reason I know a lot about it is because I didn’t study it in college. If I did study it during my time there, it’s quite possible that I would have chosen it for some practical reason, which would have made me approach it with indifference or perhaps even disdain.

The truth is, I’m a relative newcomer to both those fields of study. I’ve always enjoyed reflecting on the big questions of life, but it’s only in recent years where I’ve actually dedicated my attention to studying the great thinkers of the past and present. But because I’m doing so with complete agency, I’m able to learn more in one month than what an average student may learn in a year.

That sense of agency is the most crucial part of learning, and one of the great riddles of the 21st century is how to cultivate it in our youth.

Here’s the good news: The internet has provided the supply-side infrastructure for any self-learner to thrive. Education is not only information-rich, it’s entertainment-dense. People have made careers out of making learning fun, and if you can somehow stay focused on YouTube without going down a distracted rabbit hole, you’ll learn something very memorable in whatever field you’re interested in.

The question is on the demand-side, and it has to do with cultivating the desire to learn. Curiosity is often quelled by the (supposed) lack of an interest’s practicality. Parents want their kids to play the piano, but rarely do they want them to be professional pianists. It’s more for “practical” reasons – like optimizing for the parts of their brain that will help them think better or that they learn how to perform for others.

So how do you cultivate the desire to learn? Well, the first thing is to decouple an interest from its practical value. Instead of embarking on something with an end goal in mind, you do it for its own sake. You don’t learn because of the career path it’ll open up, but because you often wonder about the topic at hand.

The second is to understand that a pursuit truly driven by curiosity will inevitably lend itself to practical value anyway. The internet has massively widened the scope of possible careers, and it rewards those who exercise agency in what they pursue. More To That is the result of my inner child running wild, allowing it touch whatever it wants to explore further. And then by applying the work ethic from my inner adult, the outline of a newfound career path begins to emerge.

Interestingly enough, the compass of curiosity has taken me back to economics, which I’ve been delving back into quite a bit. But this time around, I have total agency over what I want to explore, and nothing that I’m studying has any obvious practical value for me.

Ironically, that framing is precisely what makes it so valuable.

_______________

_______________

For three more stories and reflections of this nature: