The Skill That Will Never Die

Like many of you, I’ve been experimenting with AI. I’ve been using ChatGPT to summarize my favorite books, been toying around with Claude for some editing tips, and have been curious about building apps with it as well.

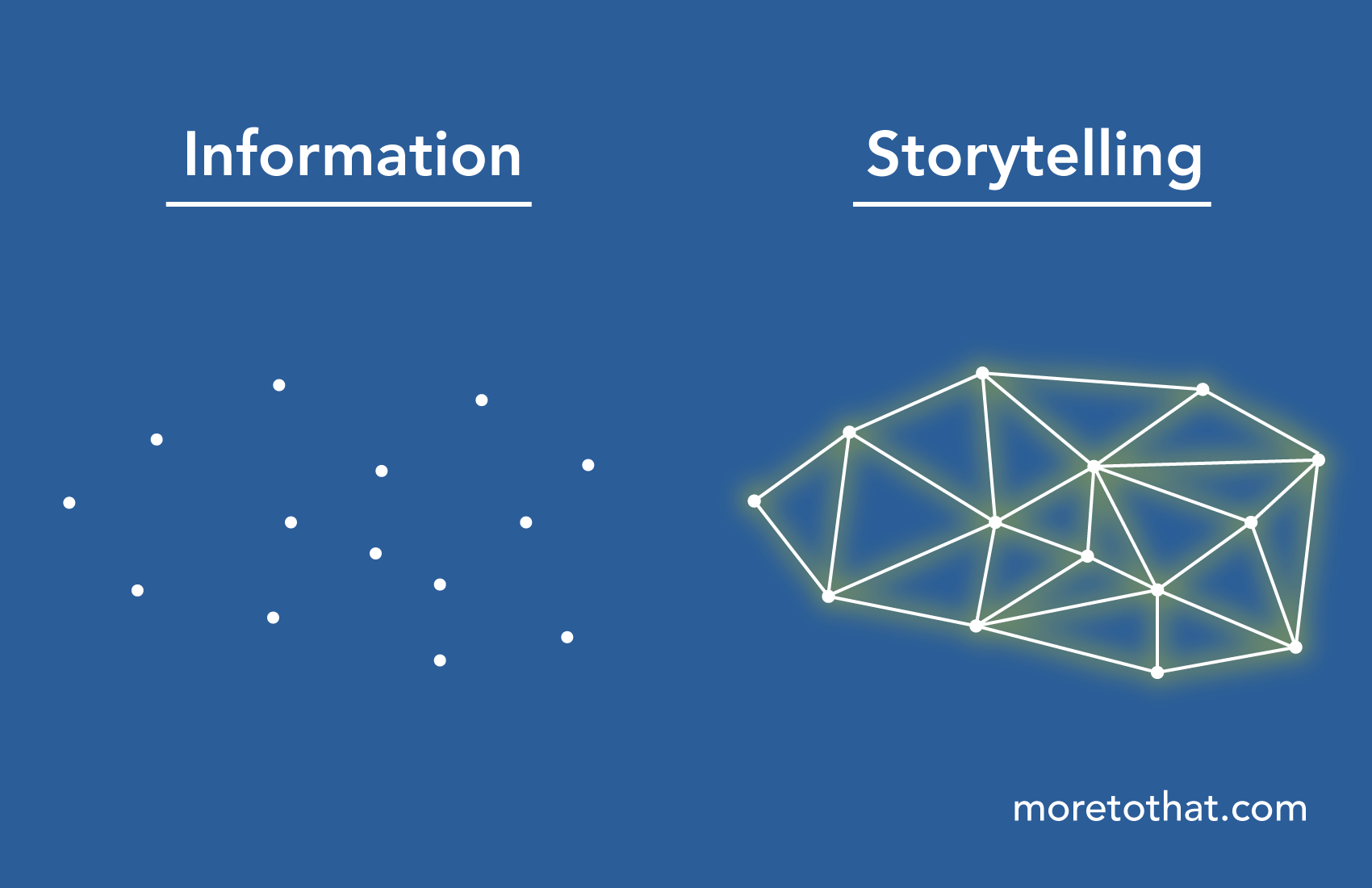

One thing that’s becoming abundantly clear is that information is no longer precious. Information was once a valuable commodity that was made expensive through gatekeepers, but technology has systematically broken through each gate to make knowledge accessible to the masses.

On one hand, this is liberating because everything we want to know is just a prompt away. But on the other, this is concerning because we wonder if our minds will be made obsolete. After all, if AI holds the key to all recorded human thought, then what can we possibly produce that will contribute more value than that?

Well, this was a concern I had until I started to look deeper into our relationship with technology.

Marshall McLuhan had a theory that technology is an extension of our physical bodies. For example, the car is an extension of our legs, as it has enabled us to travel great distances that our legs would’ve found appalling. The same goes for the phone being an extension of our voices. Technology takes any natural function we have and greatly expands the surface area of what it can touch.

This is why Steve Jobs famously referred to a computer as “the bicycle of the mind.” The natural function of the mind is to think, to solve problems, and to commune with others. The computer extends our capacity to carry out those functions on a global scale, and this has reshaped the world into what it is today.

If the computer was the bicycle of the mind, then perhaps AI is its rocketship. But what I find interesting is that both are still technologies. In other words, they are both instruments that the mind uses, and are not substitutes for the mind itself.

When we worry about AI making us obsolete, we assume a fundamental error. That error is in mistaking creativity for the ability to recall factual information. Because if that were the case, then sure, AI has surpassed anything we could ever do in that domain.

But that is not the natural function of the mind.

The function of the mind is to process information and to interpret it according to its unique perceptions. It’s not a fact-gathering machine, but an opinion-generating one. It attempts to find the personal narrative that weaves through everything it knows, and will then communicate that opinion in the hopes that it will resonate with others.

In other words, AI can give you all the information you want, but that’s not what creativity is. Creativity is about finding the unique connections within those facts and communicating the result to others, and that can only be done through the skill of storytelling.

You might think storytelling is reserved for fictional beasts and magical wizards. Far from it. Storytelling is embedded in everything we do, ranging from a client meeting, a job interview, a breaking news story, to even this very post you’re reading right now. Each of these scenarios contains a narrative that is being communicated, and the way it’s framed will determine whether or not it achieves its desired outcome.

For example, I’m writing this post to tell you about the importance of storytelling, and will go into some practical techniques to go about it. Now, I could’ve started it off by simply saying, “I think storytelling is an extremely important skill for you to learn. Here’s how to cultivate it.” But that would merely be information, which would read like something ChatGPT might say. Instead, I started it off with an anecdote about how I’ve been using AI, some of the concerns I’ve had about it, along with a brief discussion about Marshall McLuhan’s work and a Steve Jobs quote as well.

I want to craft a compelling argument about why you should care about storytelling in the first place, and to do that, I have to construct a narrative. That is where creativity comes into play, which is all about digging into one’s own interests and experiences to convey a unique perspective. I guarantee you that if you asked ChatGPT to write a piece about storytelling in my style, it wouldn’t look anything like the opening paragraphs of this piece. That’s because ChatGPT isn’t me, and it never will be.

Storytelling is a skill that’s only to become increasingly valuable over time. As the value of information nears zero, what will become precious are the human minds that can piece together information in a creative way. As Morgan Housel said, “everything is sales.” Those that will survive in the 21st century will know how to persuade, and those that will thrive will be the ones that do it ethically.

Storytelling is the most ethical form of persuasion there is, as you’re not relying on psychological hacks or gimmicks to get what you want. Rather, you’re relying on ingenuity, creativity, and connection to find the people you want to sit around a cozy intellectual campfire with. Storytelling forges deep personal connections with those that have resonated with your work, and these bonds will only strengthen over time.

Knowing this, where does one begin?

Well, the key to storytelling is to first begin with you: the storyteller. This sounds painfully obvious, but so much of storytelling advice doesn’t take this into account. People will tell you to build out a 3-act structure or map out a Hero’s Journey before encouraging you to first reflect on what matters to you. Everything begins with an exploration of the issues you care about most, and then extending that out into a theme that you can build a story around.

This process requires a deeper dive, which I’m happy to do together. Let’s jump right in.

The Problems That Matter Most

Take a moment to think of the books that have impacted you most. Better yet, take a look through some of the quotes you’ve highlighted in recent memory or recall some of your favorites.

For example, here are three that come to mind for me:

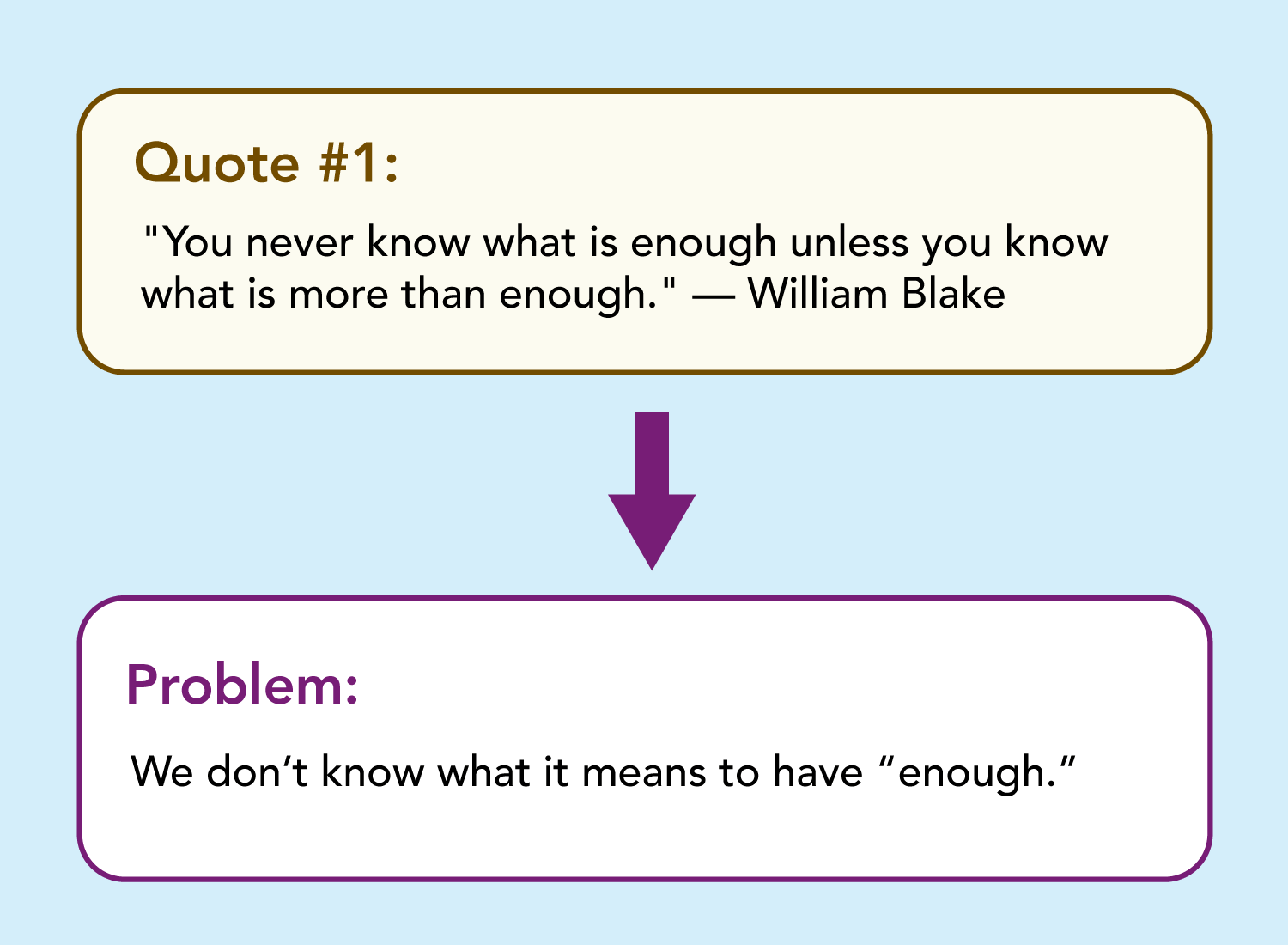

(1) “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” — William Blake

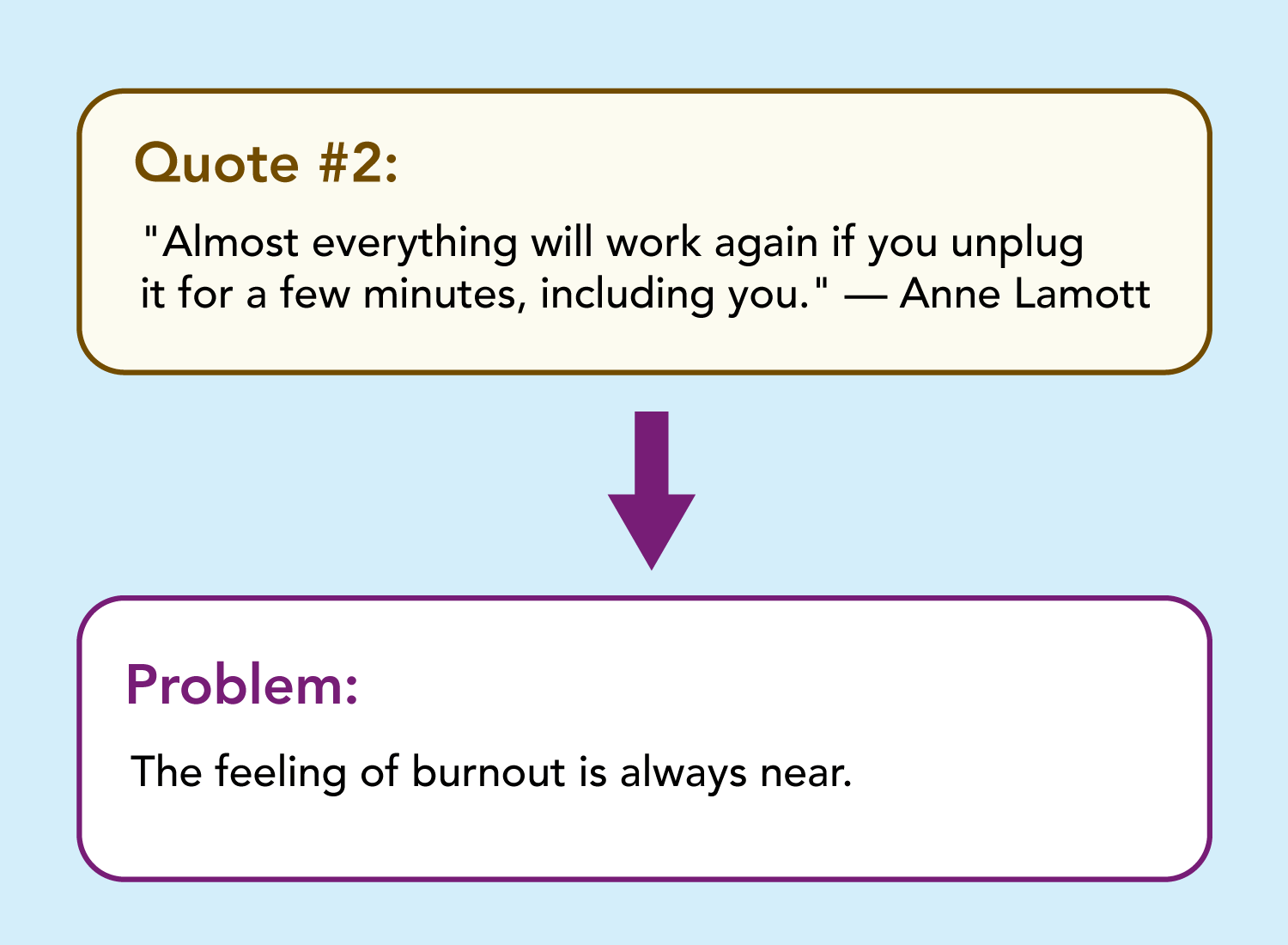

(2) “Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes, including you.” — Anne Lamott

(3) “Suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.” — Viktor Frankl

Now, these three quotes all address different things, but they have one thing in common:

They all address problems that I care about.

Anytime you highlight something, there’s an implicit statement that this tidbit of information offers an insight into a problem that matters. This is the case for every single highlight you make.

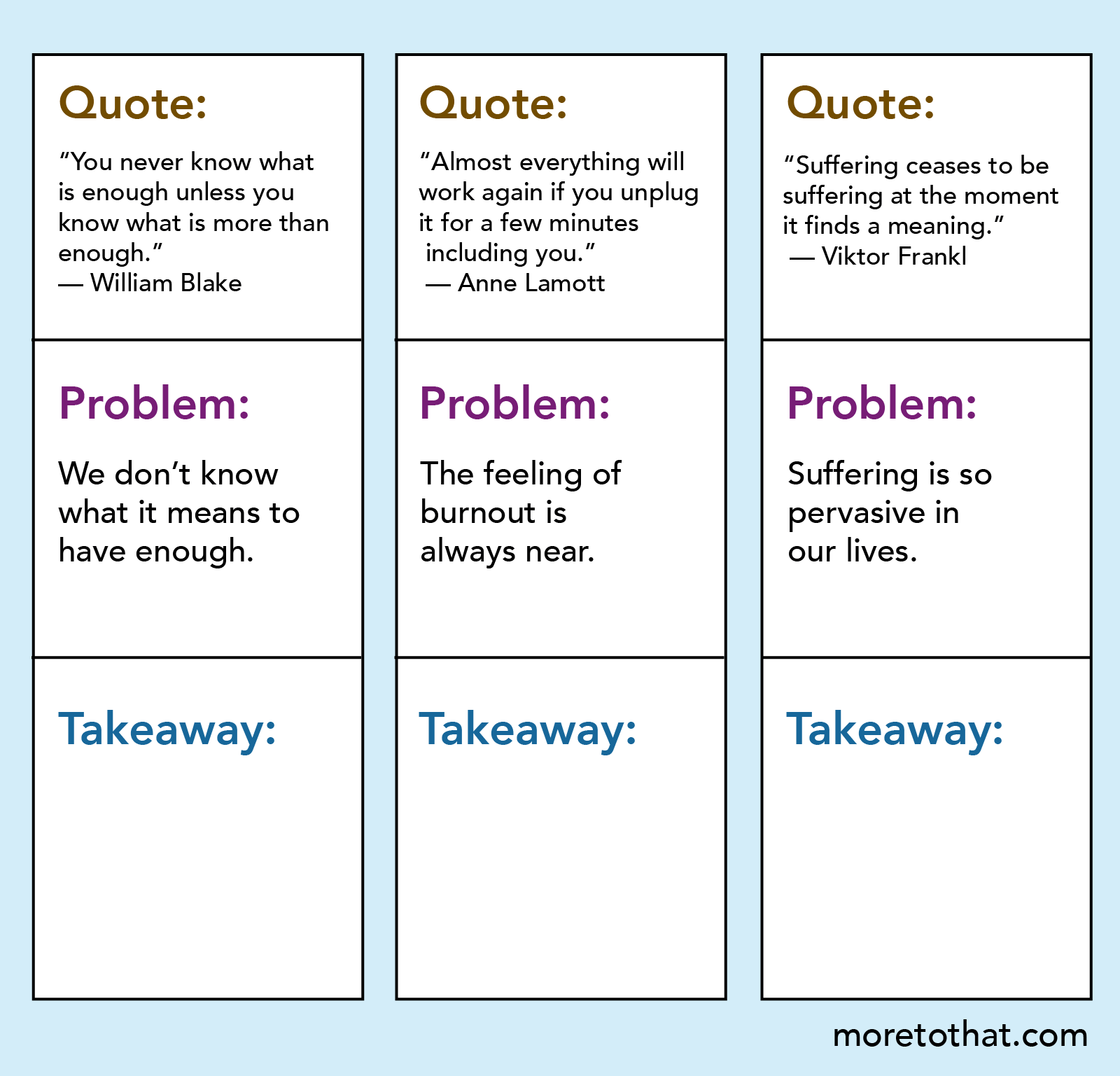

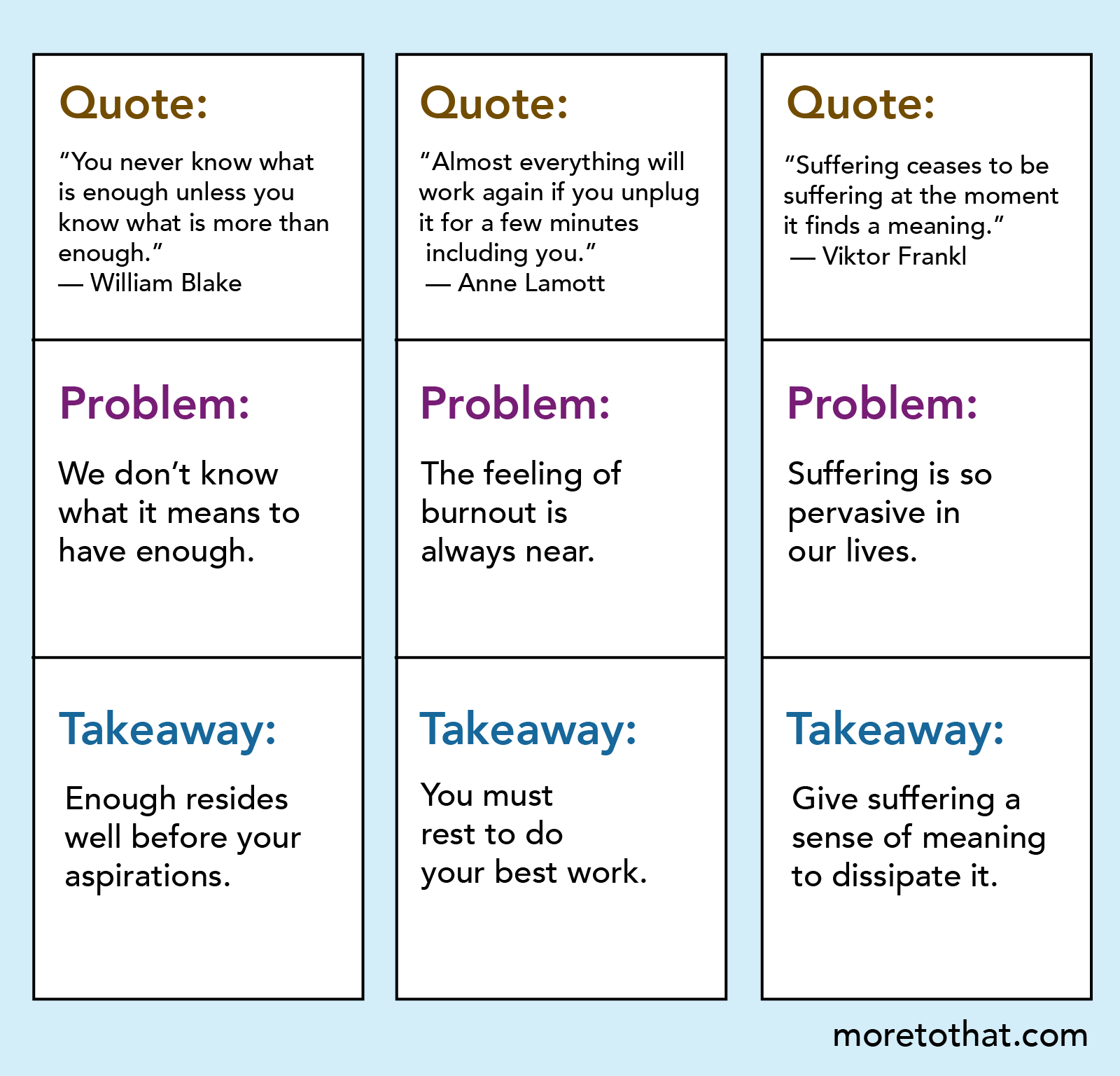

Let’s look at the 3 quotes I referenced above and unearth the problems they address:

When I look at the above three problems, it makes sense that I remember these quotes so much. The problem of “enough”, of burnout, of suffering… these are all things I’m deeply interested in. I find myself grappling with these issues in my own life, and these quotes give me a much-needed boost of clarity that help me stay centered.

Interestingly, the omission of certain quotes will also say something about me as well. For example, you will see zero highlights in my Reader app about how to drive faster or how to dress better because I don’t give a damn about horsepower or fashion. (It’ll take just two seconds of hanging out with me to see that fashion isn’t an issue I care about.)

But will you see a ton of quotes in there about the meaning of life? About what it means to be knowledgeable? About cultivating creativity? Yes, yes, and yes. That’s because I care deeply about those problems, and love reading about them as a result.

The first step to being a great storyteller is to gain clarity on the problems you care about most. This is the launchpad from where everything begins, and it requires you to ask yourself what problems are most salient to you. Chances are, this isn’t an exercise you do often, but it’s important to get in the habit of doing it if you want to craft stories regularly.

So I’d advise you to pause and write down your response to this question:

If responses don’t come to you naturally, then take a look at your bookshelf or some notes you’ve taken recently. What are the problems embedded in them? What are some of the obstacles they address?

I view this as the start of a Problem Log that you can continue filling out over time. The nature of your problems will evolve, but you can rest assured knowing your life will never be devoid of them (nor would we want that either).

The key shift here is to move from merely experiencing your problems to actually documenting them. Take inventory of what they are, as they will reveal the unique storytelling identity you embody. While many people may share interest in your individual problems, only you will have the precise combination of problems that you care about.

Treat these problems as the origin point of all your stories. Once you do, you’ll naturally gain clarity into the endpoint, which is where we’ll dive into next.

The Theme of Your Story

Theme.

This is one of those words that we’ve all heard before, but if someone were to ask you to define it, you’ll likely have a hard time coming up with an answer.

Let’s see how our friends at Wikipedia define it:

Uh… I don’t know about you, but that left me more confused than anything.

This is the issue with so much storytelling advice. People make it far more complicated than it needs to be, and you’re also unsure of how to make it fit within the context of non-fiction.

So in an attempt to simplify it, here’s the definition of a theme:

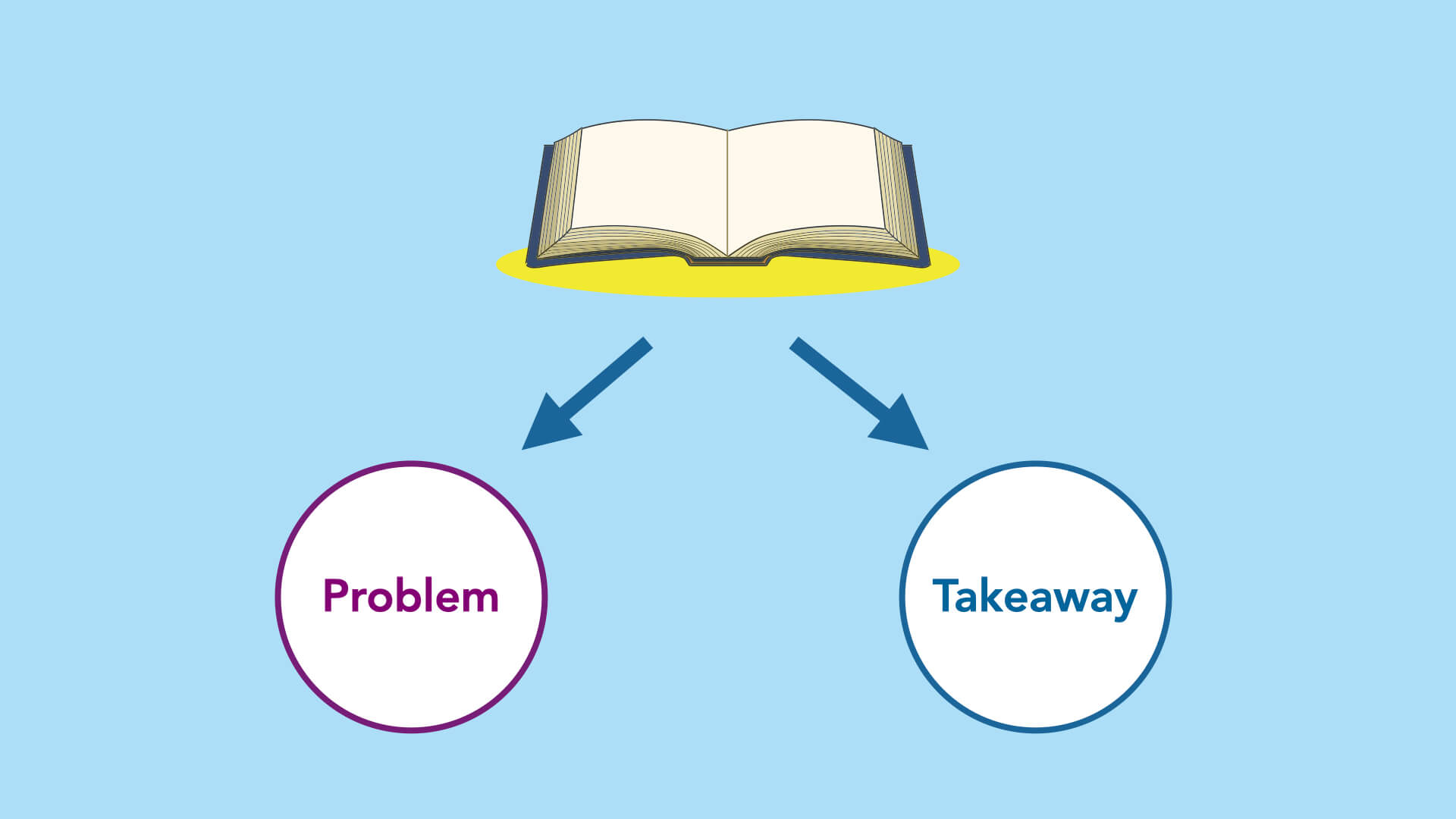

It’s the problem your story addresses, and the takeaway it provides.

That’s it.

If you can nail down these two components in advance, then you’ll have an anchor that will ground your story as you tell it. It will keep your message focused, while also giving you room to play with tangents and such knowing where the story will ultimately end up.

Now, if you did the exercise from earlier, you’ll have a few problems you can choose from when it comes to the theme. That represents the first half of the equation. But what about the second half, which is the takeaway?

This is a good time to re-visit some of the quotes you used to extract problems from. Because the beautiful thing is that they also contain the takeaways that help to resolve the very problem they address.

And once again, here are the problems that each of them address:

You’ll notice that each quote also contains a resolution, or in our words, the takeaway. If it only contained the problem, we may not find it that insightful. But because it also offers a dose of clarity, we highlight it and keep it stored.

For the sake of simplicity, I’ll choose one quote and discuss the takeaway it provides. Let’s choose this one from Anne Lamott:

Now, we know that this quote addresses the problem of burnout, which is something I struggle with as well. But what does it offer in the form of a takeaway? Or in other words, what is the solution that she offers?

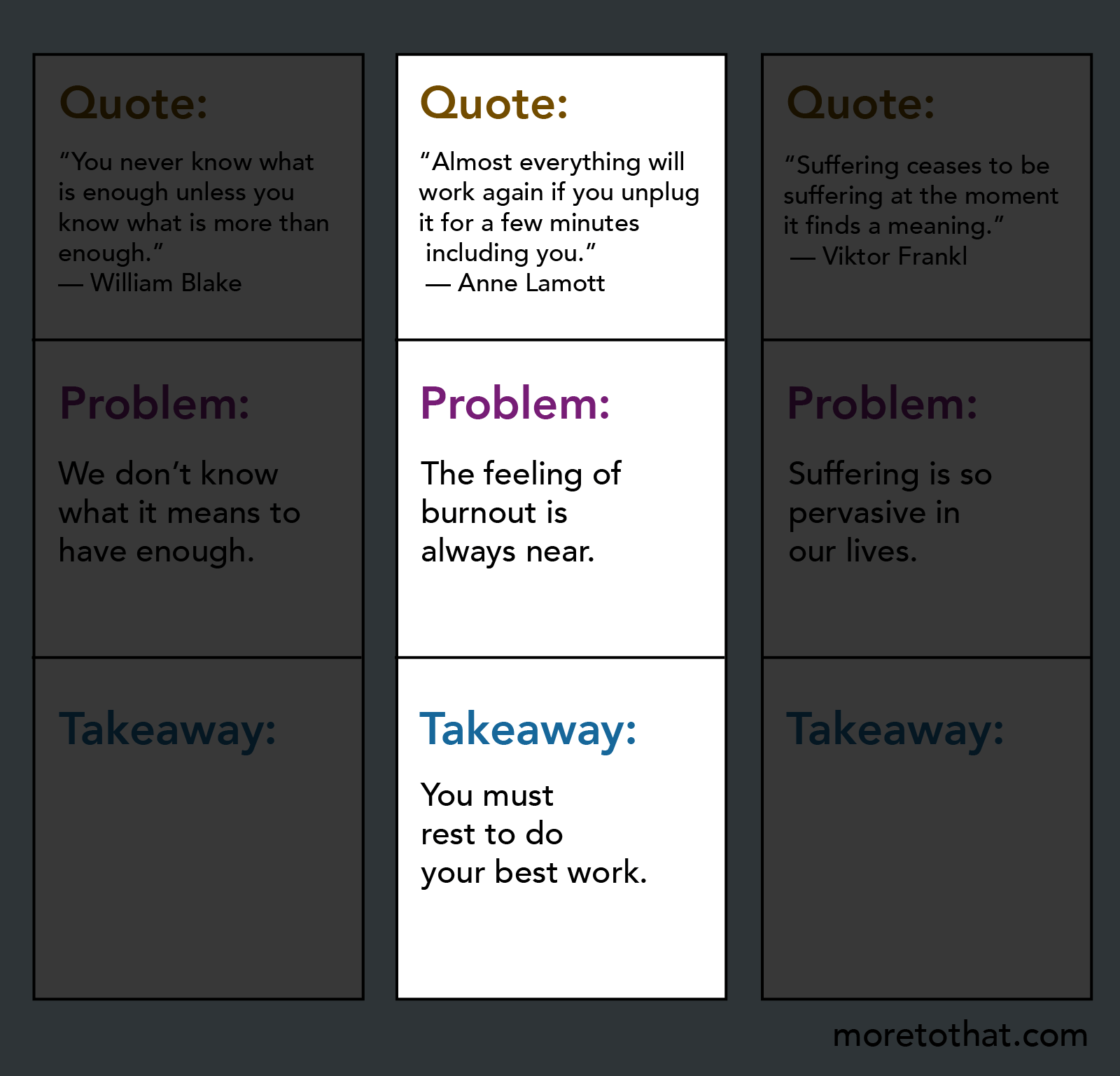

Well, what she proposes in that quote is a call to rest. That when your mind is in overdrive, you need to unplug it for a few moments so it can recharge and remain open to experience. That paradoxically, these periods of unplugging are what actually lead you to produce your best work.

So here is the theme that emerges from that one Lamott quote:

Do you see how you now have a starting and ending point for a story? Your story will address the problem of burnout, and will urge the reader/viewer to rest. This came from breaking down a highlight into these two components, and the cool part is that you can do this for any quote you come across.

In fact, let’s do it for the other quotes we had as examples:

From these 3 quotes, we now have 3 themes we could embed into a story. And it all came from seeing each of them through the lens of a Problem and a Takeaway.

A common pain point I hear from writers is that they have nothing to write about. But I never hear them say that they have a shortage of notes and highlights. The reality is that these highlights contain themes that act as a treasure trove of topics that are already tailored to your interests. You don’t need to look elsewhere for them, as the problems you care about already live within the information and art you consume.

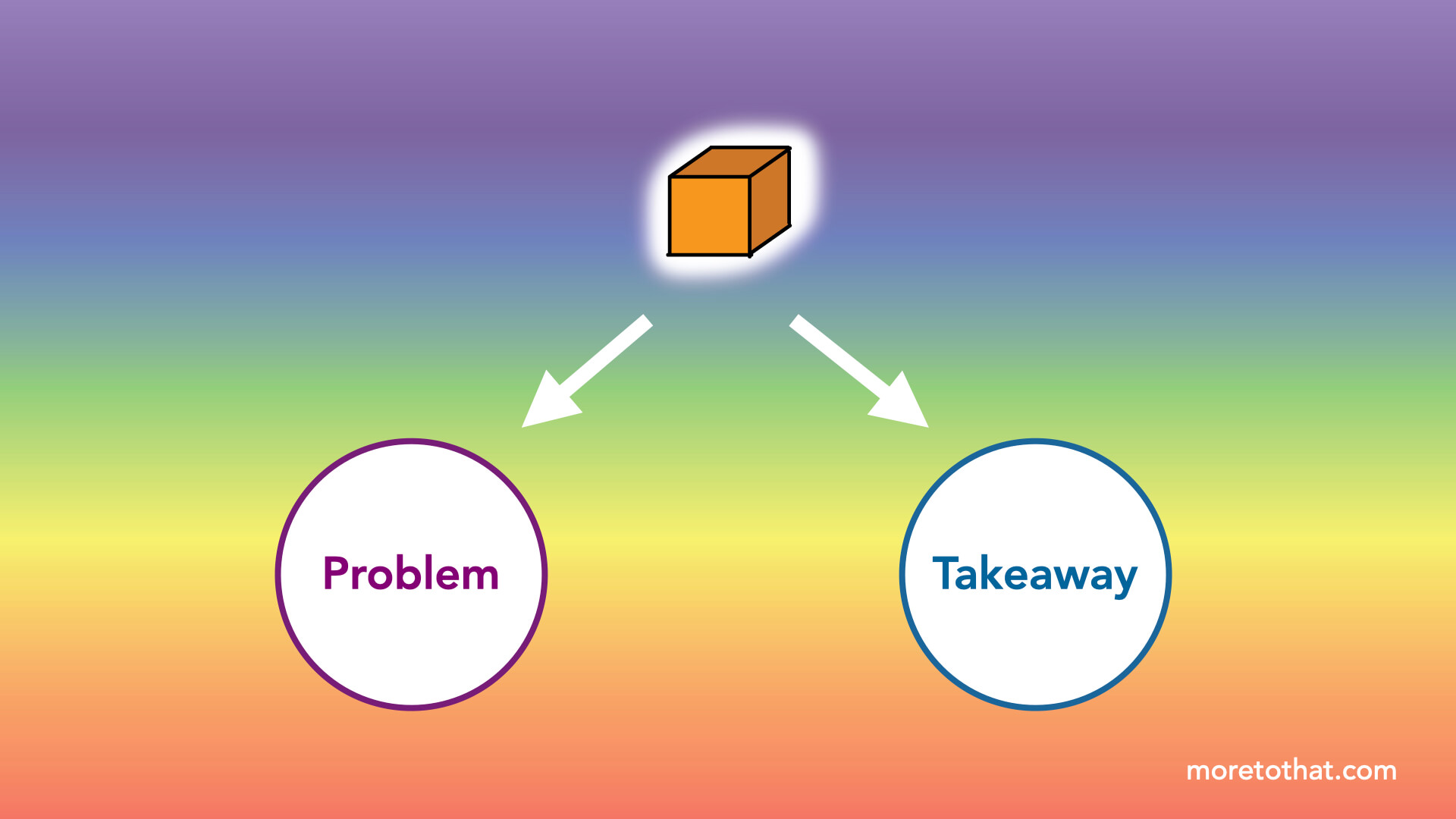

The first step to becoming a storyteller is to see the world through the lens of themes, or what I aptly call the Thematic Lens:

When you come across an idea, break it down into a problem and a takeaway. Whether you make a mental note or capture it somewhere, get into the habit of seeing themes in the sentences that resonate with you. If you do this regularly, then you will always have a starting point for a story of your own.

In Thinking In Stories, you’ll have the space to practice doing this with your own saved ideas. Every step we go over is followed up with an opportunity to implement, which is what makes it a habit over time. This is how the art of storytelling is demystified, as I will break everything down into concrete steps that are actionable. No confusing diagrams of Hero’s Journeys or 3-act structures; just a highly practical method that you can apply to any idea of your choosing.

Using the Thematic Lens is just the first of these steps, but what you’ll realize is that everything stems from your interests and curiosities. As long as your stories originate from that root, you’ll be able to protect yourself from the onslaught of AI-generated content. No one will have the exact combination of themes that you care about, along with the way you’re going to present them. And as long as that’s true, then no large language model can accurately convey the nuances of what you’ve experienced and felt.

Storytelling is the skill that will never die because it pulls from the core of the human experience. And given that we connect with those that share that core, your ability to tell stories will be valued regardless of what the future has in store.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts: