The Power of the Dissenting Voice

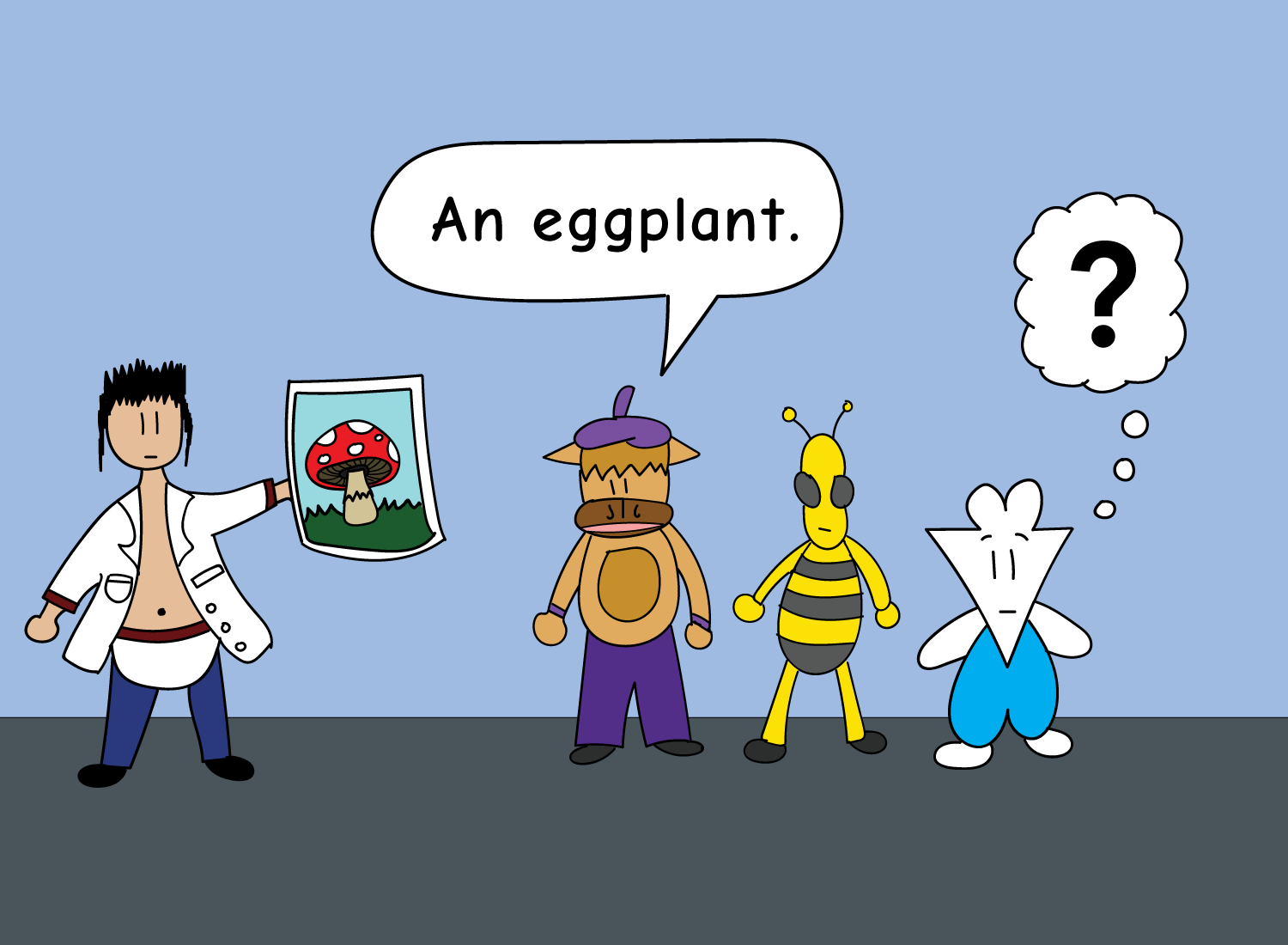

Imagine that you were part of an experiment that went something like this:

Pretty straightforward, eh?

Okay, now to make this remotely interesting, let’s add some new variables into the mix.

In our revised experiment, we have the same photo and question, but this time, there’s a line of other people present as well:

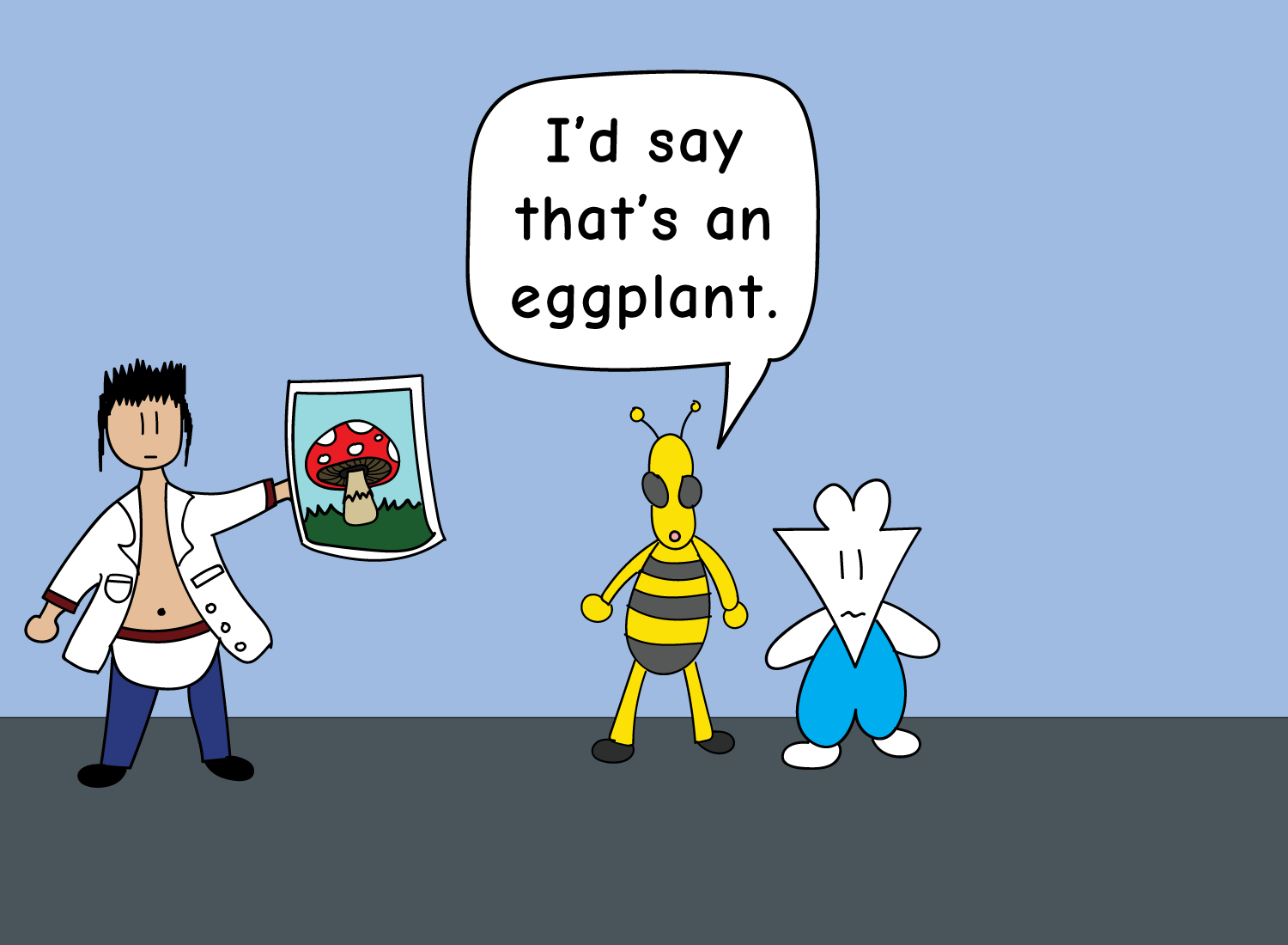

And with this setup, here’s how the situation unfolds:

How do you think you’d reply here? Would you go with “mushroom,” given that’s what’s clearly being shown? Or would you go with “eggplant,” given that everyone else seems to think it is?

This is my silly version of psychologist Solomon Asch’s conformity experiments, where he found that in this particular situation, there was a decent chance you’d say “eggplant” as well. Through a series of studies, Asch found that intelligent people often went against their own intuitions to go with the opinions of the crowd.

In other words, the pressure of social conformity was powerful enough to disconnect one’s rational faculties.1

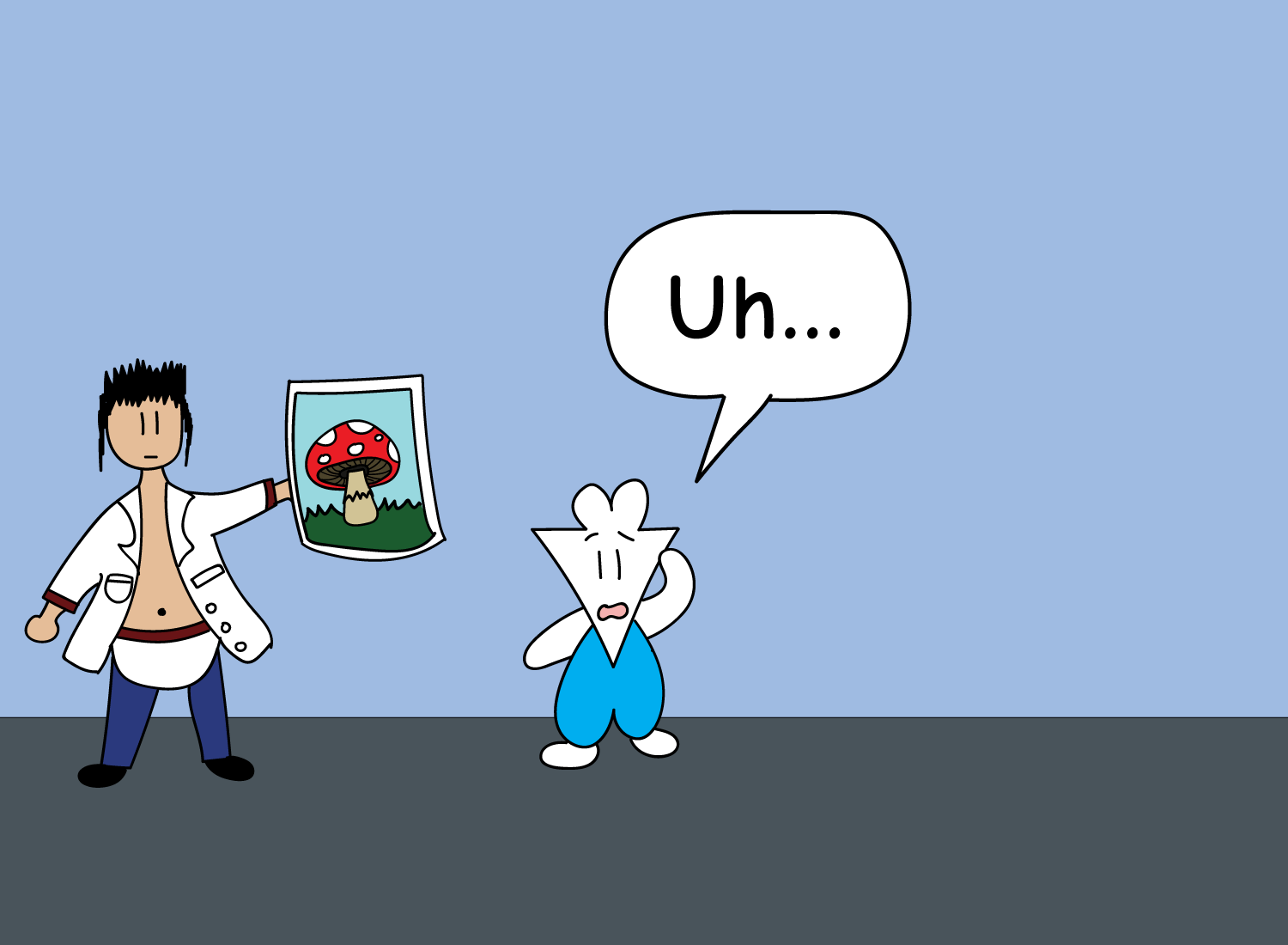

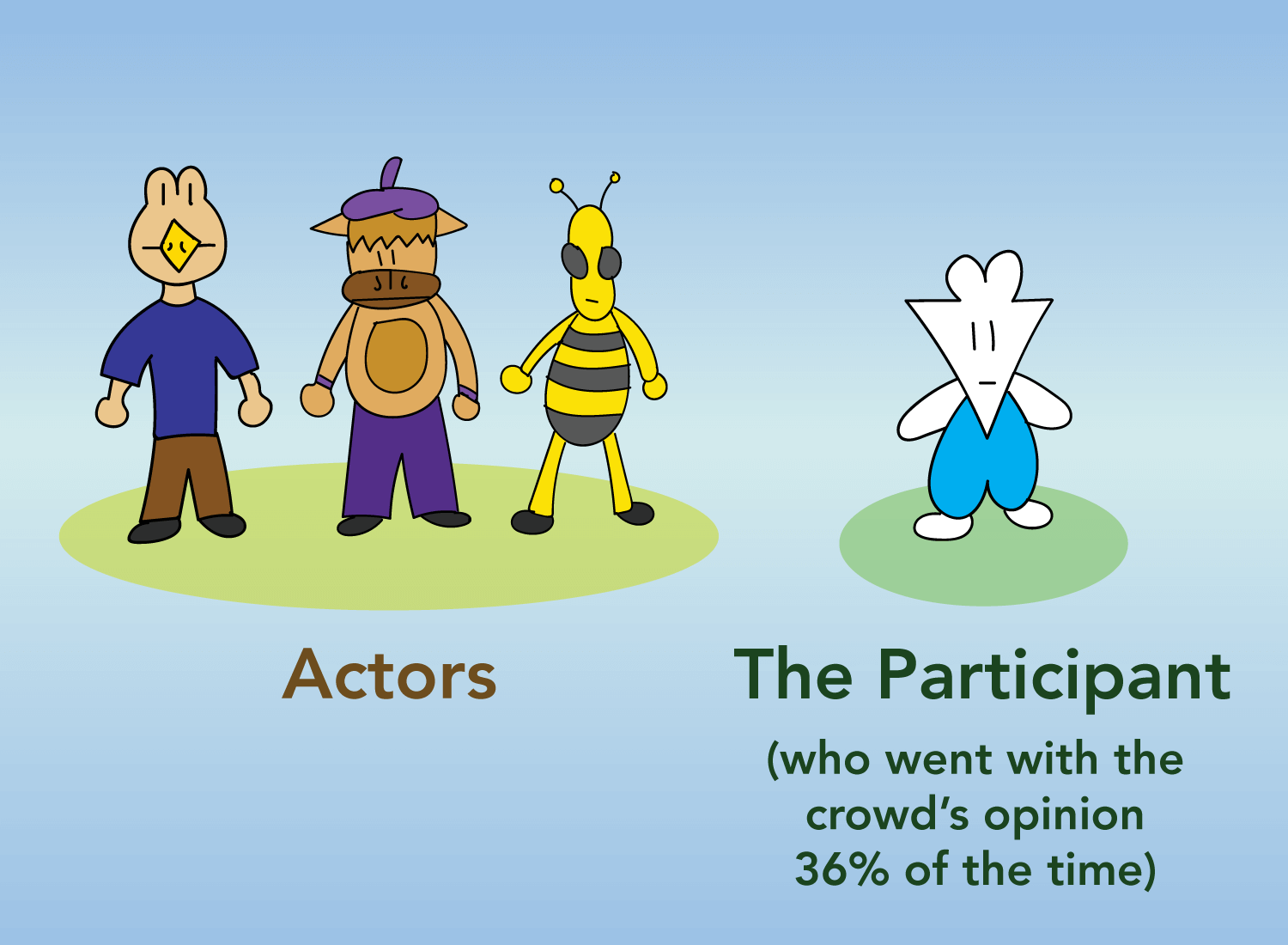

This was most noticeable in Asch’s original experiment, where everyone but the final respondent was an actor that was told to give the erroneous answer beforehand. In these trials, the focus of the experiment was on the unsuspecting participant, and how he or she would respond to the behaviors of others.

While this version of the experiment is well-known, Asch conducted a lesser-known version a few years later that I find even more interesting.

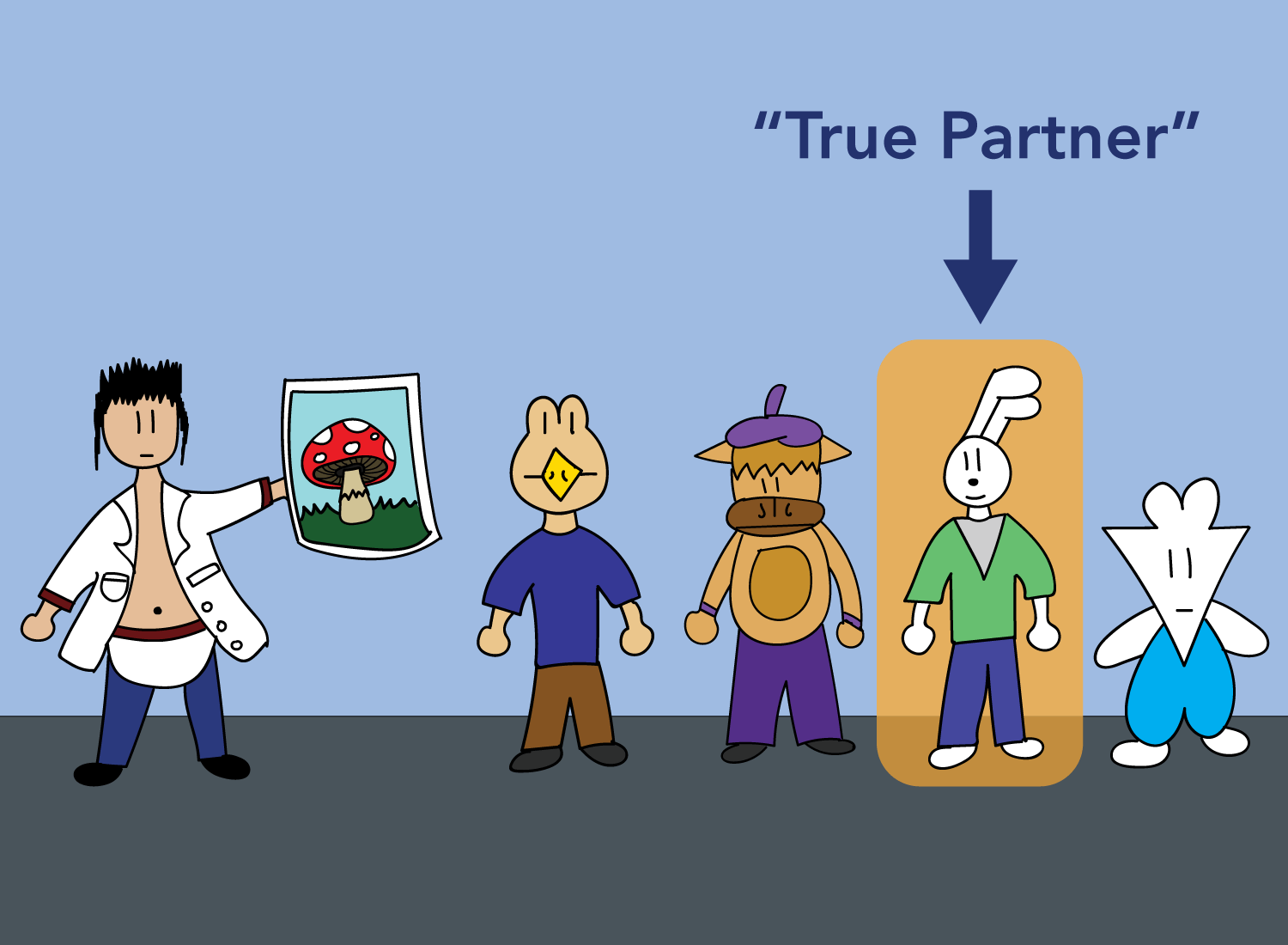

The setup of the experiment was the same, but this time, Asch designated one person to be a “true partner.” This was someone who was either a real participant or an actor told to give the correct answer instead. He wanted to see what effect this one person might have on the final respondent’s tendency to conform to the group.

The results were dramatic.

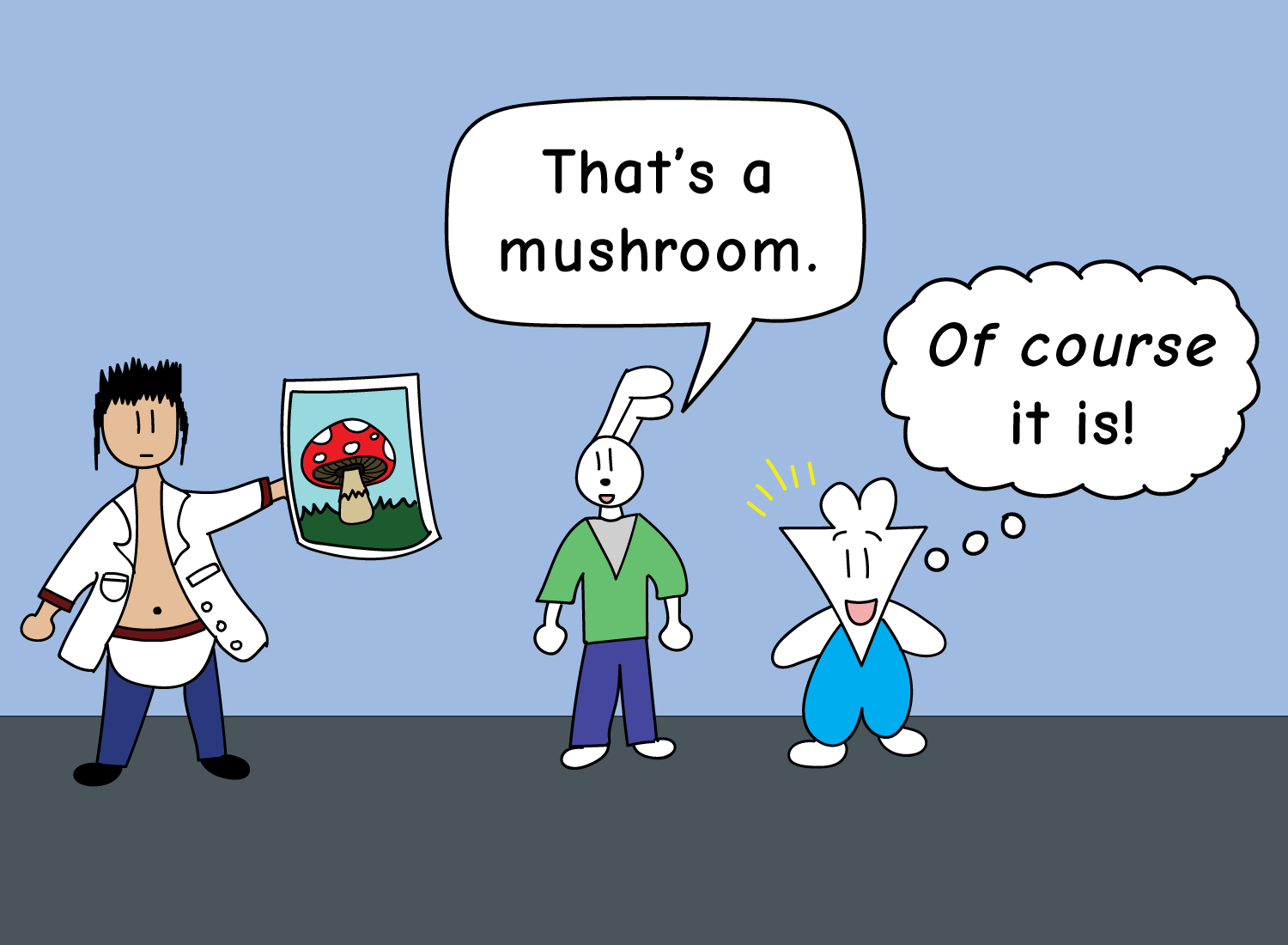

Having just one person there to give the correct answer drastically decreased the participant’s pressure to conform. Only 5% of the participants continued along with the majority, as opposed to the 36% seen from the original experiment.

One dissenting voice can empower you to go with your gut.

Of course, the real world isn’t a controlled environment where people are told to give wrong answers by some psychology professor to trick you. The pressures of social conformity are much more subtle, embedded into the behavioral patterns we all fall into without much thought.

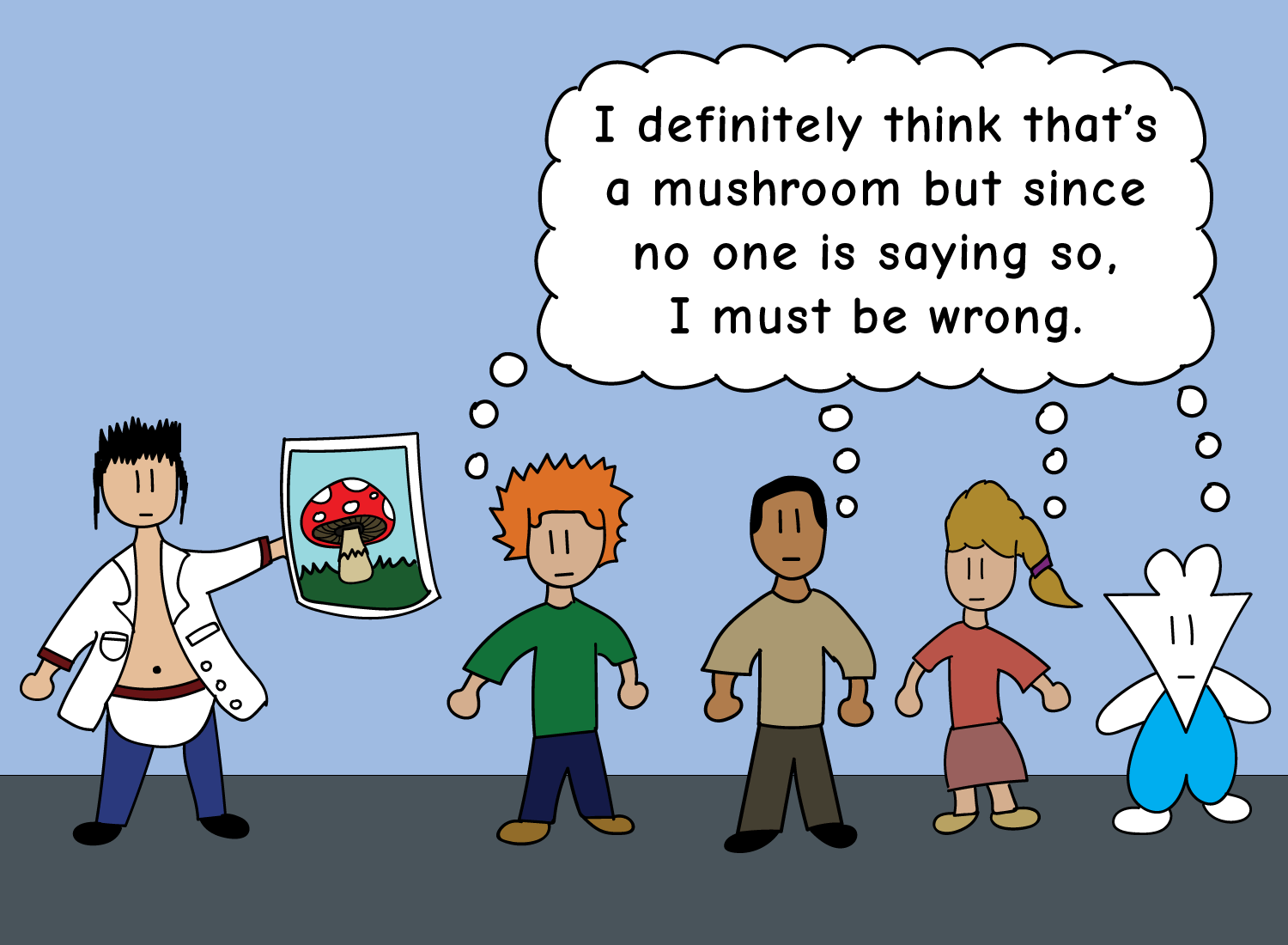

Perhaps the most common version of conformity we encounter is a phenomenon called pluralistic ignorance. This is when many members of a group are doubting the dominant view, but since no one else is expressing their doubts, they think they’re the only ones that have the dissenting opinion. As a result, they suppress their doubts and and simply go along with whatever the majority is thinking.

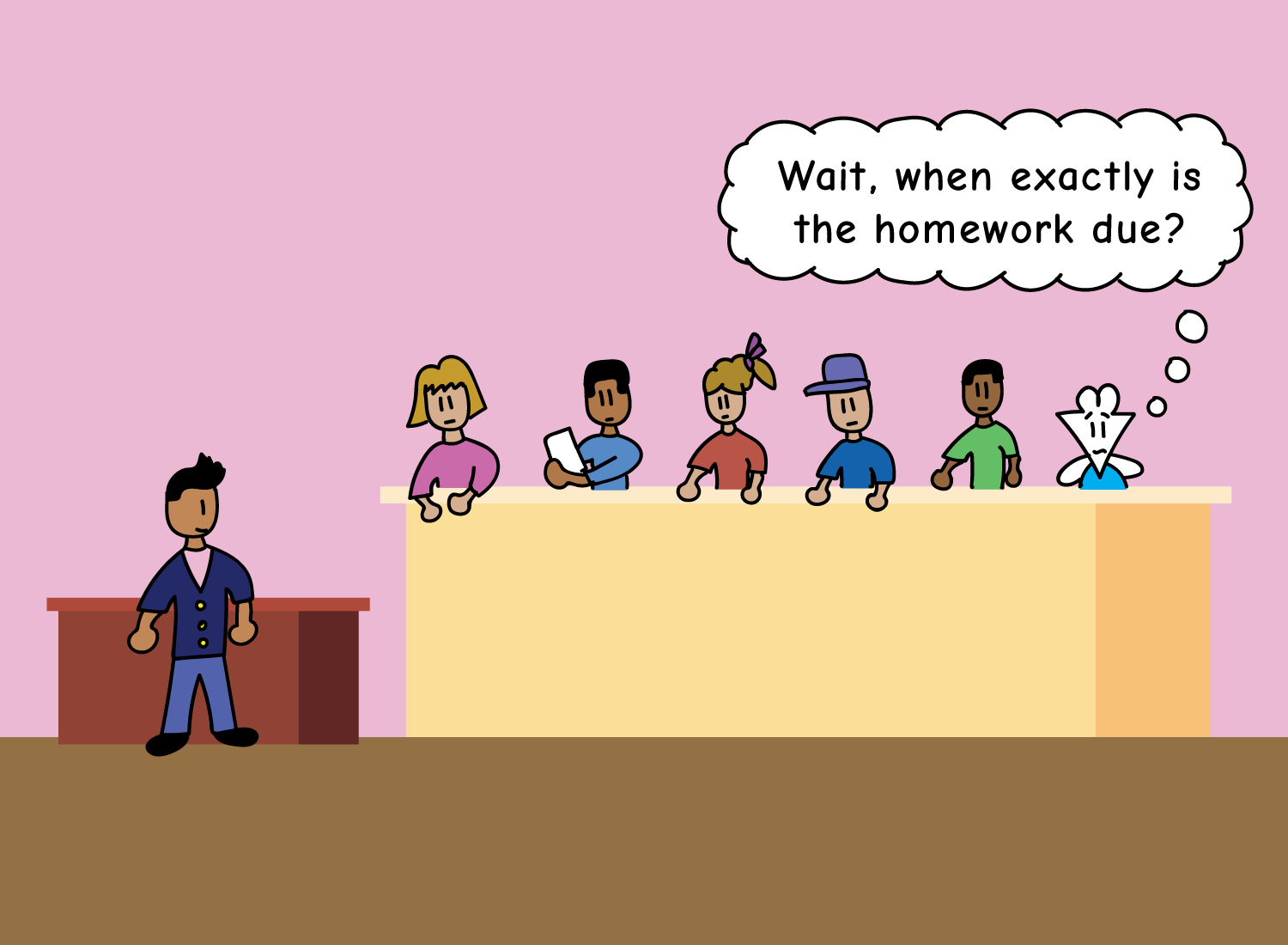

A common example of pluralistic ignorance occurs in classroom settings. At the end of a lecture, the teacher will generally ask, “Any questions?”, to which the entire class usually responds with silence. Even if you have a pressing question, you may hold off from asking it because you think it’ll make you look stupid. Since no one else is asking anything, it might feel like you’re the only one that doesn’t have shit figured out.

The reality, however, is that everyone else is thinking the same thing, but isn’t expressing it because no one else is.

And in this situation, the savior is the person that puts her hand up and asks the damn question anyway, much to everyone’s (secret) relief.

The spell of pluralistic ignorance is usually broken with one ardent voice. If one person voices what everyone else is thinking, what was initially a minority opinion can quickly become the majority.

This highlights the big difference in marginal value between a consensus opinion, and a dissenting one. Whereas each additional consensus voice doesn’t make much impact, a single dissenting voice has the power to bring the entire argument down. 10 people all saying the same thing is far less interesting than the 1 person that has a reasonable, opposing view.

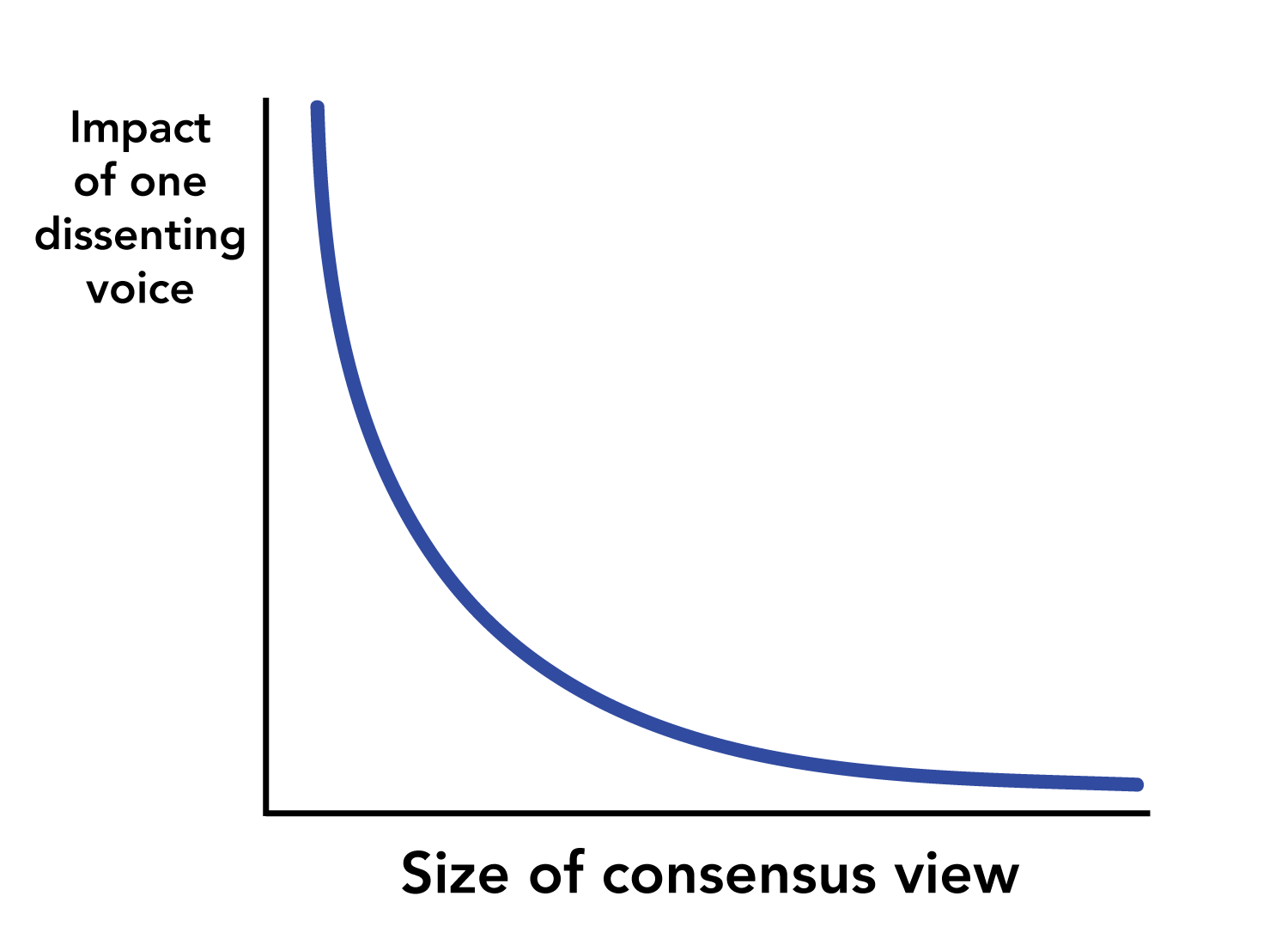

But the impact of a single dissenting voice decreases exponentially as the size of the consensus view grows. In a small group of people, that voice may be enough to sway everybody else. In a huge group of people, however, that voice can get drowned out quickly, or suppressed the moment it arises.

So the relationship between the impact of one dissenting voice vs. the size of a consensus view follows an inverse power law, like below:

This graph screams out one conclusion:

If you don’t agree with a consensus opinion, make it known earlier than later. The longer you wait, the less your voice will be considered and heard.

In Asch’s experiments, this conclusion had light-hearted consequences. By having a “true partner” voice the correct answer beforehand, it was able to break the spell for our unsuspecting participant. But even if it didn’t, the worst that would happen is that the participant might feel a bit embarrassed at the end of the study. Not a big deal at all.

However, what happens when a consensus view is something you disagree with morally? What if the pressure to conform isn’t about calling a mushroom an eggplant, but about whether or not a group of people should be persecuted?

The inverse power law also applies here. If you see something wrong – and you know in your gut that it’s wrong – your voice is at its most impactful in the beginning. Because in those early stages, dissenting voices are at their most powerful, and have the ability to flip the conversation.

However, sometimes those crucial opinions aren’t voiced due to a combination of pluralistic ignorance and fear. In the best case, this is somewhat comedic, like office cultures that make liberal use of their expense accounts. It’s not the most honest thing to do, and everyone knows it’s happening, but it’s not putting anyone’s life in jeopardy.

But in the worst case, this leads to a societal ballooning of deeply immoral views, where that society becomes intolerant of any dissenting opinion whatsoever. The consensus view, despite its repugnance, has taken advantage of the silence and grown to take over.

And it is in this environment that we get perhaps the scariest outcome of all:

Normal people doing the most horrendous of deeds.

Conformity and the Banality of Evil

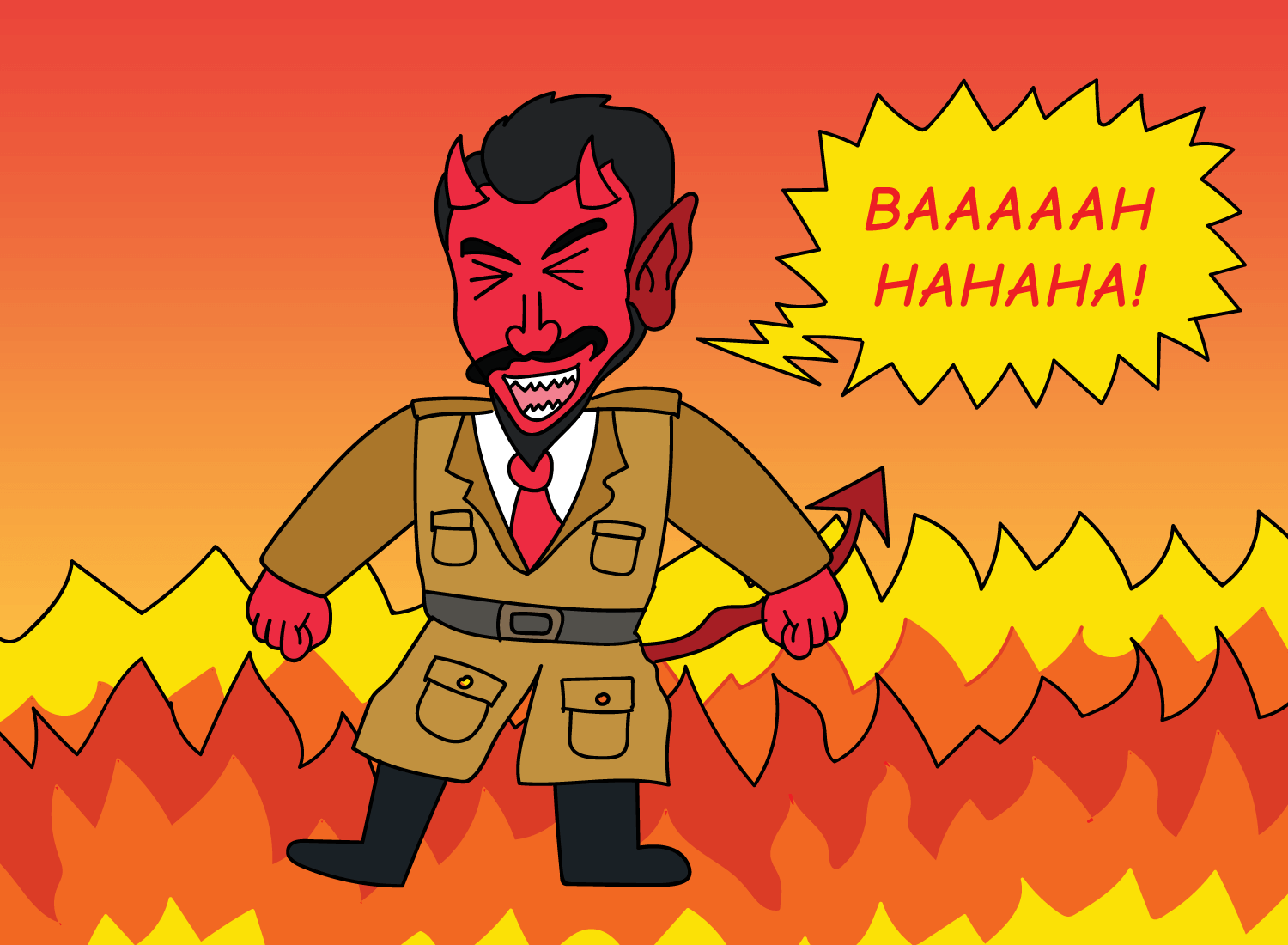

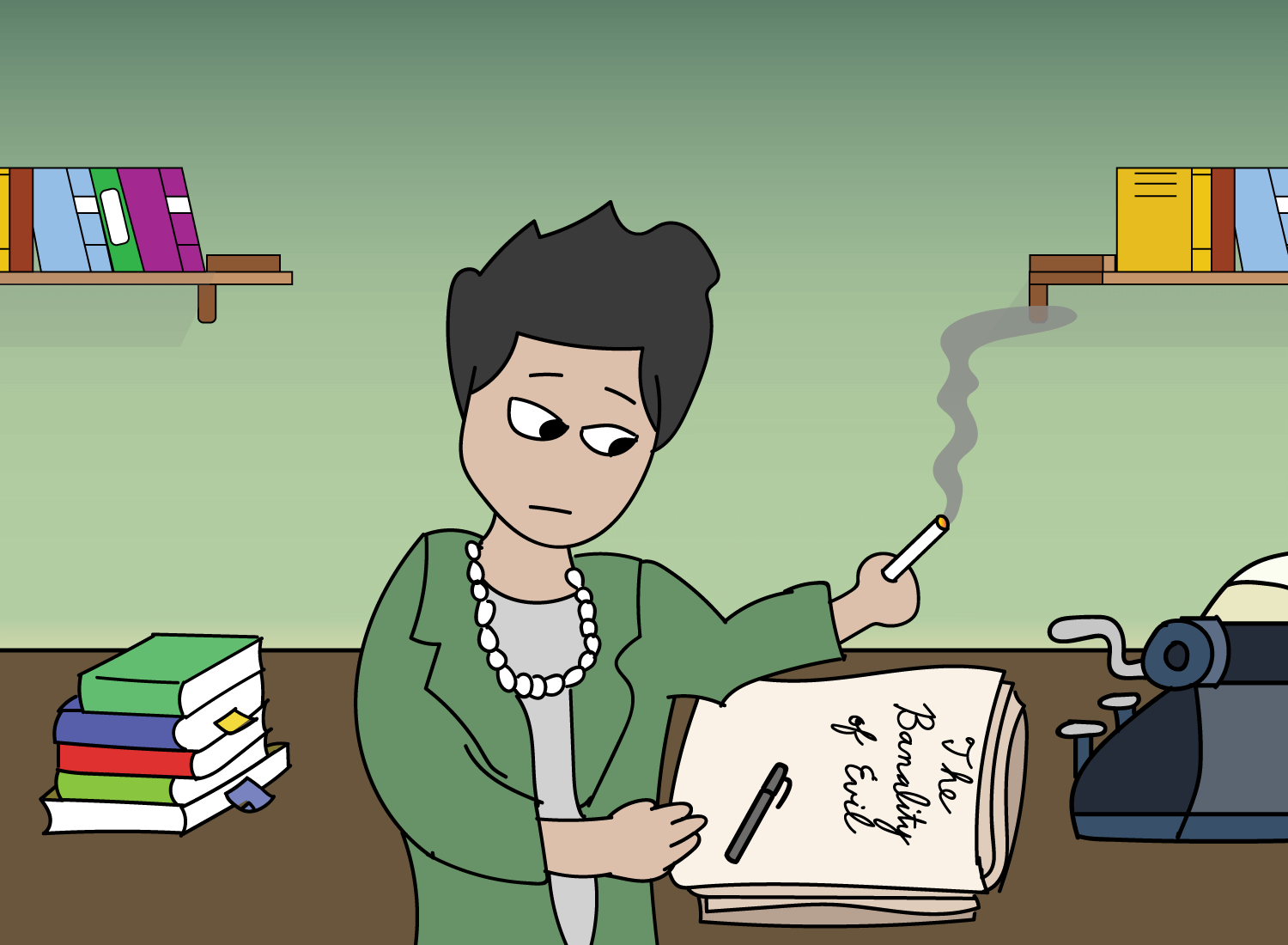

In 1962, political theorist and philosopher Hannah Arendt went to Jerusalem to report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust. Given the scope and magnitude of his crime, Arendt initially assumed that Eichmann would be some sort of demonic, psychopathic mastermind that utilized his intelligence and charisma in the worst way possible. After all, as a top official in the Third Reich, one might imagine him to look something like this:

But what Arendt actually saw was much more horrifying.

She saw a man that was terribly, unfathomably…

Mediocre.

Arendt saw a man who spoke with zero charisma, used boring cliches, and wasn’t an evil genius by any stretch of the imagination. He wasn’t particularly smart, nor did he seem insane or crazy either.

He was a thoroughly unoriginal person, and ultimately, was just a man who lived by the opinions of others. In Arendt’s words:

What he said was always the same, expressed in the same words. The longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else.

Another observation Arendt made was that Eichmann didn’t seem to be driven by an insane and all-consuming hatred for the Jews. This was something that ran counter to the intuitions people had about Nazis at the time. Instead, she saw that Eichmann was motivated by the simple desire to do his desk job, to move up the bureaucratic ladder, and to “obey the law.”

In other words, he didn’t appear to be driven by genocidal hatred. He was motivated by something far more mundane:

An office promotion.

Arendt pooled these observations together and called it the banality of evil. She realized that evil and wickedness didn’t manifest in the form of villains and hateful beings. In reality, it develops in the minds of normal people that want nothing more than to be a part of something. All they want is an identity, and if they can’t find it themselves, they want someone else to give it to them.2

This is why the most unremarkable human beings are capable of the most unspeakable horrors. Even if they recognize the immorality of their deeds, the desire for group identity allows evil to sweep in and blind them to that conscience. This all-too-normal tendency to conform – and how it could open the doors to malice – is what shook Arendt the most.

When I think about the banality of evil, I don’t relegate it to the horrors of the mid-20th century. Although it’s the clearest historical example of this phenomenon, it exists in much smaller scales everywhere, and at any moment today.

It’s in the 13-year-old kid that wants to go to college, but his family members are all gang members that want him to continue their legacy. If he commits a heinous crime in the near future, how much of that is due to his wickedness, and how much of it is because he just wants to make his family proud?

Is there anything more normal than wanting to make your family proud?

We see the banality of evil in a man that wants to be recognized by his colleagues, but he works in a setting where bosses regularly defraud and cheat investors. If he steals money from an unsuspecting client, how much of it is because he’s an evil thief, and how much of it is because he just wants to be respected by his peers?

Is there anything more normal than wanting to be respected by your peers?

What makes the banality of evil possible in the first place, however, is just one thing:

An immoral consensus view that has gone unchallenged for too long.

What’s most astonishing about the rise of the Nazi party in Germany was that they didn’t seize power through a vicious coup. No. They were elected.

Does this mean that the German population entered the voting booths with hatred in their hearts, wanting to annihilate millions of people with each vote? It might be tempting to think that, but the banality of evil points to another conclusion.

Through the pressures of conformity and the longing for group identity, otherwise normal people piled their support onto a horrific consensus view and allowed it to grow in power. And as shown on our graph from earlier, the larger that group becomes, the less a dissenting voice has the ability to sway opinion over to the other side.

The scariest thing about the banality of evil is that it can scale all the way up to the greatest atrocities of humankind, and scale all the way down to the decisions made by a single person. To believe that any individual is immune to its grasp is laughable at best, and fatal at worse. This is because evil is never as obvious as a maniacal, demonic supervillain that brands itself as such. Rather, it manifests in the minds of normal people that believe they’re doing all the right things for all the right reasons.

Conformity and pluralistic ignorance sound like fun concepts when they make people call a mushroom an eggplant. But what happens when they prevent us from speaking up when we see something morally wrong, all because no one else is doing so? Or when we think that the wisdom of the crowd is what we should follow, without realizing that many constituents of that very crowd also have the same doubts as you do?

The only way to break that spell is to make your thoughts known, particularly in the early stages. That is when a single dissenting view is at its most impactful, as it opens the door for other people to speak up freely as well. The longer one waits, however, the more difficult (and in some cases, dangerous) it can become to assert that view. This is when the banality of evil is at its fiercest, having been fully normalized and assimilated into even the sanest of minds.

Arendt notes that the best way to break this haze is to stop and think about what you are doing. By carving out the space to think for yourself, you develop a temporary immunity to the allures of the crowd, and can see things for what they really are. A reliance upon others’ thoughts can make even the most repugnant views look like wisdom, and by recalibrating your mind, you can step back and frame things with your true sense of what’s right and wrong.

It is only here where you can develop the confidence to say what needs to be said, regardless of how unpleasant it may be. Because through that single dissenting voice, you never know who else will be empowered to do the same.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Dissent is powerful, but being a contrarian about everything just makes you lame:

It’s Mainstream to Hate the Mainstream

Is morality ever black-and-white, or is it always shades of gray?

The Infinites Shades of Uncertainty

Why the greatest moral heroes of our time have no names: