The Labor of Inspiration

When I first started writing, I did so only when the desire emerged. It was largely reactive in nature, a way of responding to whatever pulled my attention at the time.

So if I read a book that revealed an interesting idea, I’d write to contribute my own perspective.

Or if a musing struck me while walking, I’d rush back home to start unraveling that thought on the page.

There’s a common belief that inspiration is fleeting, and that its arrival is largely unannounced. While you can set up elaborate rituals to encourage its arrival, you can’t command it to serve you. It’s akin to the rain dance: you can trick yourself into believing that water will fall once you shuffle your feet, but the rain doesn’t give a damn about your sense of rhythm. It will come when it comes.

With this view, inspiration is whimsical, following no governable pattern or physical law. It’s the closest thing to magic, as it evades scientific explanation of any sort. As a result, inspiration is commonly referred to as the muse, but I visualize it more as a fairy, going around sprinkling magical dust on people that are open to receiving it.

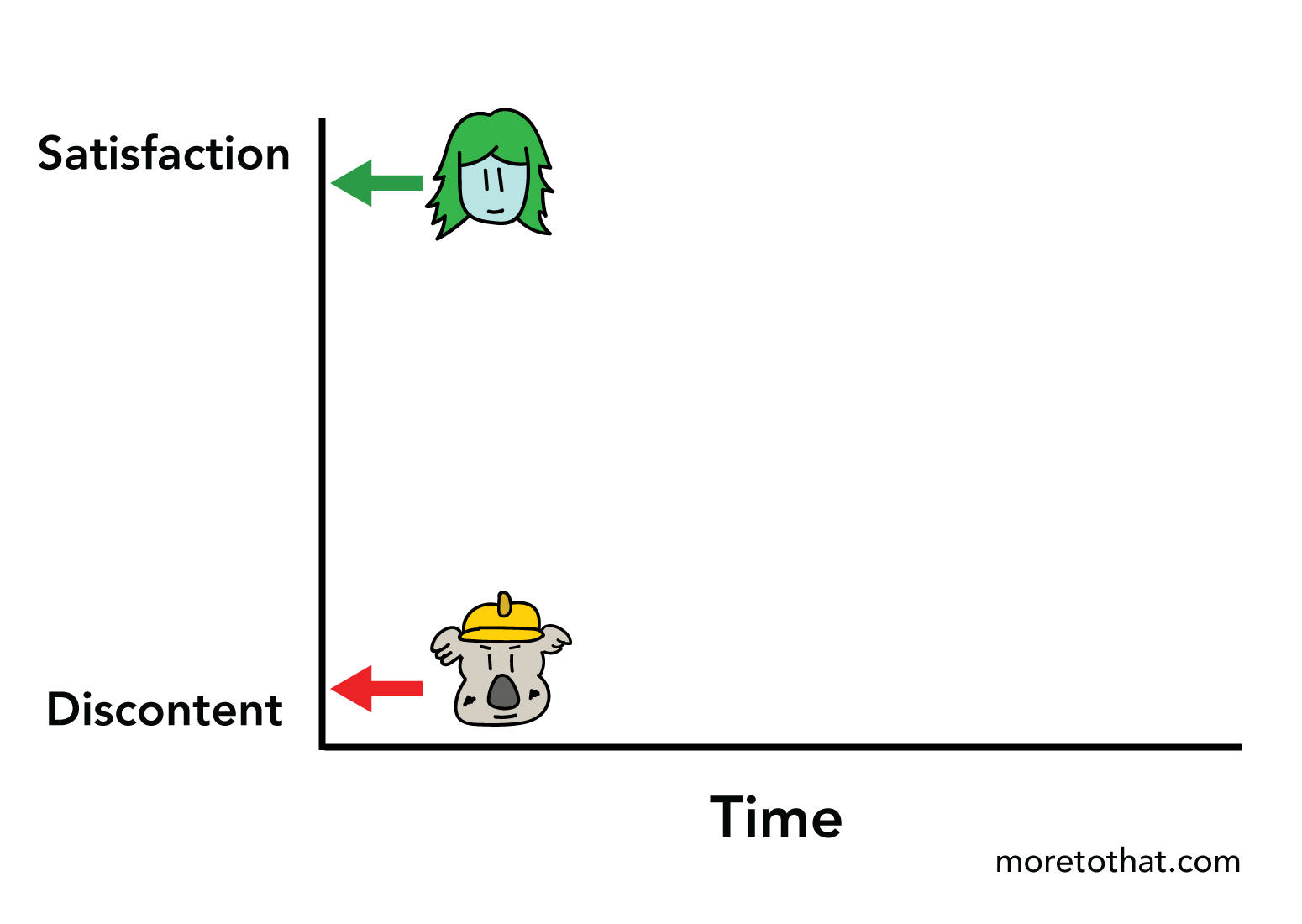

Seeing inspiration as this fairy-like creature does two things:

(1) It removes the internal pressure you may put on yourself to conjure up your “best work.” Since inspiration is an external force that visits you on its own accord, you can free yourself of the feeling that everything rests on your shoulders. You can offload some of that burden onto the unknown.

(2) You can give yourself permission to do things that don’t look like work because that’s how inspiration finds its way to you. Taking a leisurely walk or chatting with your friend may not look like a creative act, but these activities can attract inspiration in a way that sitting in front of your computer cannot. Living life outside of your workspace can be seen as a source of creativity as opposed to a repellant.

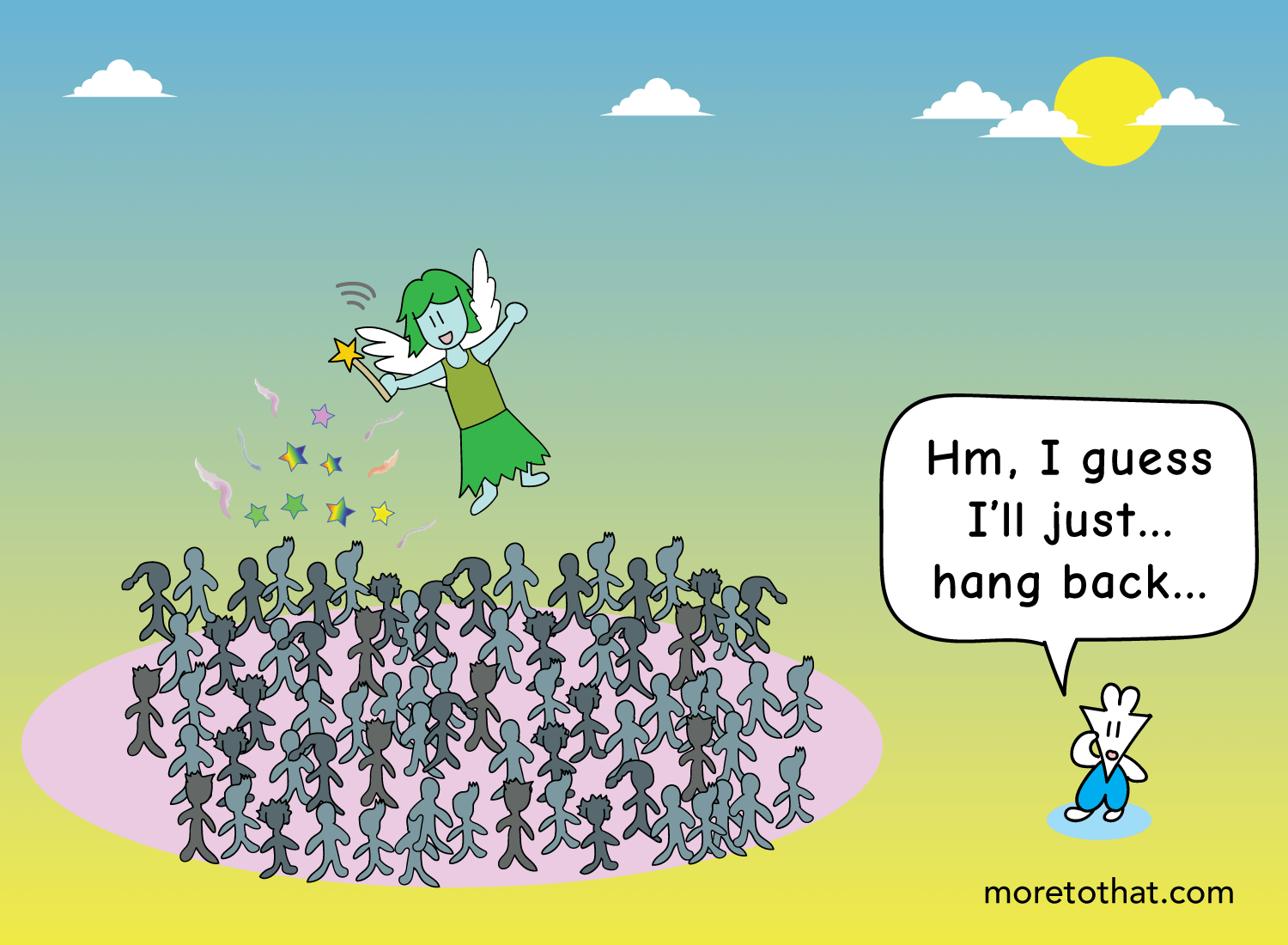

Overall, there’s a relief knowing that you can be more serendipitous with your time, and that if you didn’t think of anything to create that day, it’s okay. The fairy didn’t get to you that morning, so maybe it’ll arrive tomorrow. After all, there’s a lot of people it needs to visit, so perhaps you just need to be a bit more patient.

But here’s the thing with this approach. One day of this may be fine, but what if it becomes one week? Or one month? Or one year? At what point does your belief in inspiration’s whimsical nature become a form of justified procrastination?

This is where this caricature of inspiration begins to break down.

The downside of viewing inspiration as an external thing is that it becomes a scapegoat. It’s much easier to blame your lack of creative output on the poverty of inspiration than the poverty of personal effort. If your lack of motivation can be attributed to a third party, then it’s far too tempting to point the finger everywhere else but yourself.

So to correct for this, another caricature of inspiration was introduced. One that placed the responsibility squarely back on the shoulders of the artists themselves. One that emphasized routine over spontaneity, consistency over serendipity, and hard work over whimsical play.

Say hello to inspiration as the laborer:

A laborer shows up to his job at a set time, works for a set number of hours, and does so for a set number of days each week. Everything is mapped out in advance, and he simply needs to show up to get things in motion.

From the perspective of the laborer, you create your own inspiration. You’re not waiting for something elusive like a fairy to come and gift you with it. No, by dedicating yourself to a regimen, you remove your reliance upon an external source and make it your personal duty to motivate yourself.

As I got more serious with my writing, I realized that there’s a wisdom to this species of inspiration. I knew that I couldn’t rely upon the whims of circumstance to get my ass in a chair and write, especially because writing is a famously arduous endeavor. It’s much more enticing to go for a walk and read books than it is to sit and organize your thoughts onto a page. And if this goes on for long enough, you’ll believe that you’re living the life of a writer without actually writing anything in the first place.

So at a certain point, I decided to adopt the laborer’s mindset, sitting down at the same time to write for a lot of hours each day. Even if I had no idea what I wanted to discuss that session, I would dedicate that space to delve deeper into my intuition and discover what’s there.

When I first embarked on this path, I hated it. It was such a slog because it went against everything I thought creativity was, and everything I wanted it to be. I always believed that serendipity was the fuel for great art, yet here I was, adopting the laborer’s stance and making regimen the north star for this experiment.

But after a few days and weeks, things started to change. The first thing I noticed was that each writing session would generally be quite fruitful, even if I didn’t know how I would start each one. The reason for this, as it turns out, was quite simple. When your goal shifts from “write something great” to “write something,” you dramatically lower the barrier of the start. This allows you to explore without pressure, and you give yourself permission to pull on whatever thread you find interesting, in whatever fashion you’d like.

The other thing is the realization that intention can be enough to conjure inspiration. There’s a power in simply showing up each day with a commitment to putting in the work. Even if your ideas are undeveloped, the desire to explore them for a set period of time allows them to unravel and find their footing. And since you’re doing this day-in and day-out, you can iterate on these ideas quicker than if you were waiting around for inspiration to do it.

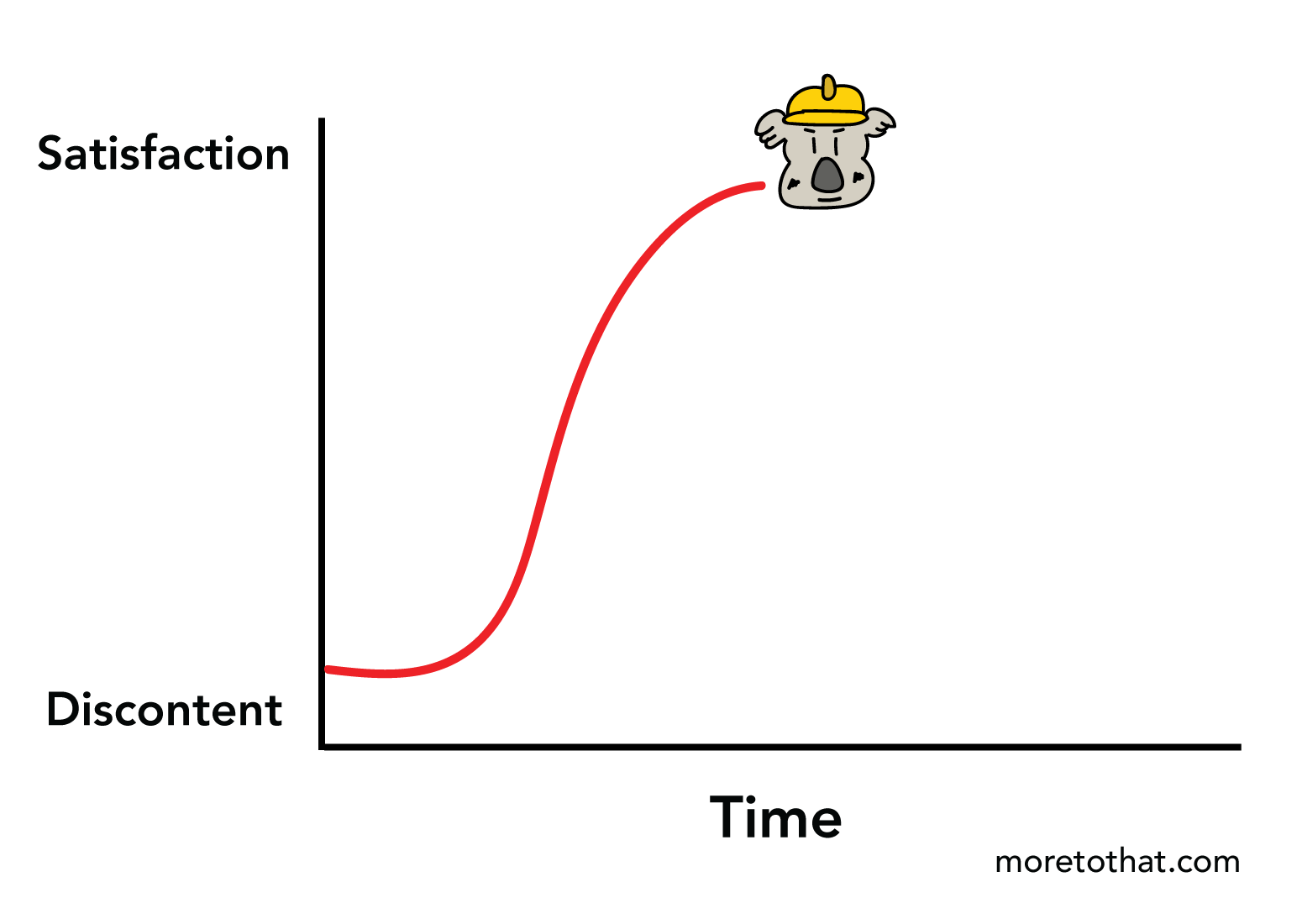

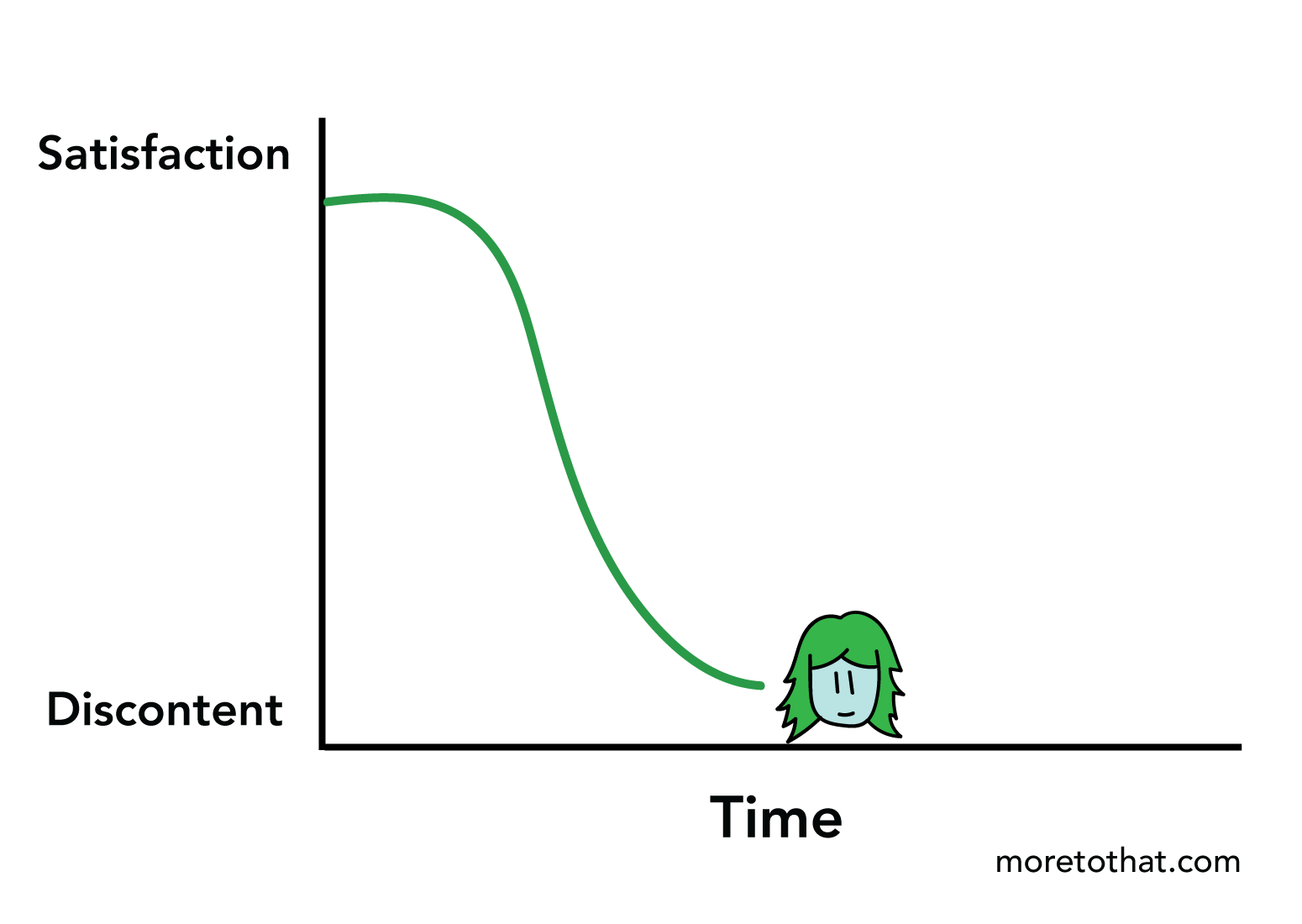

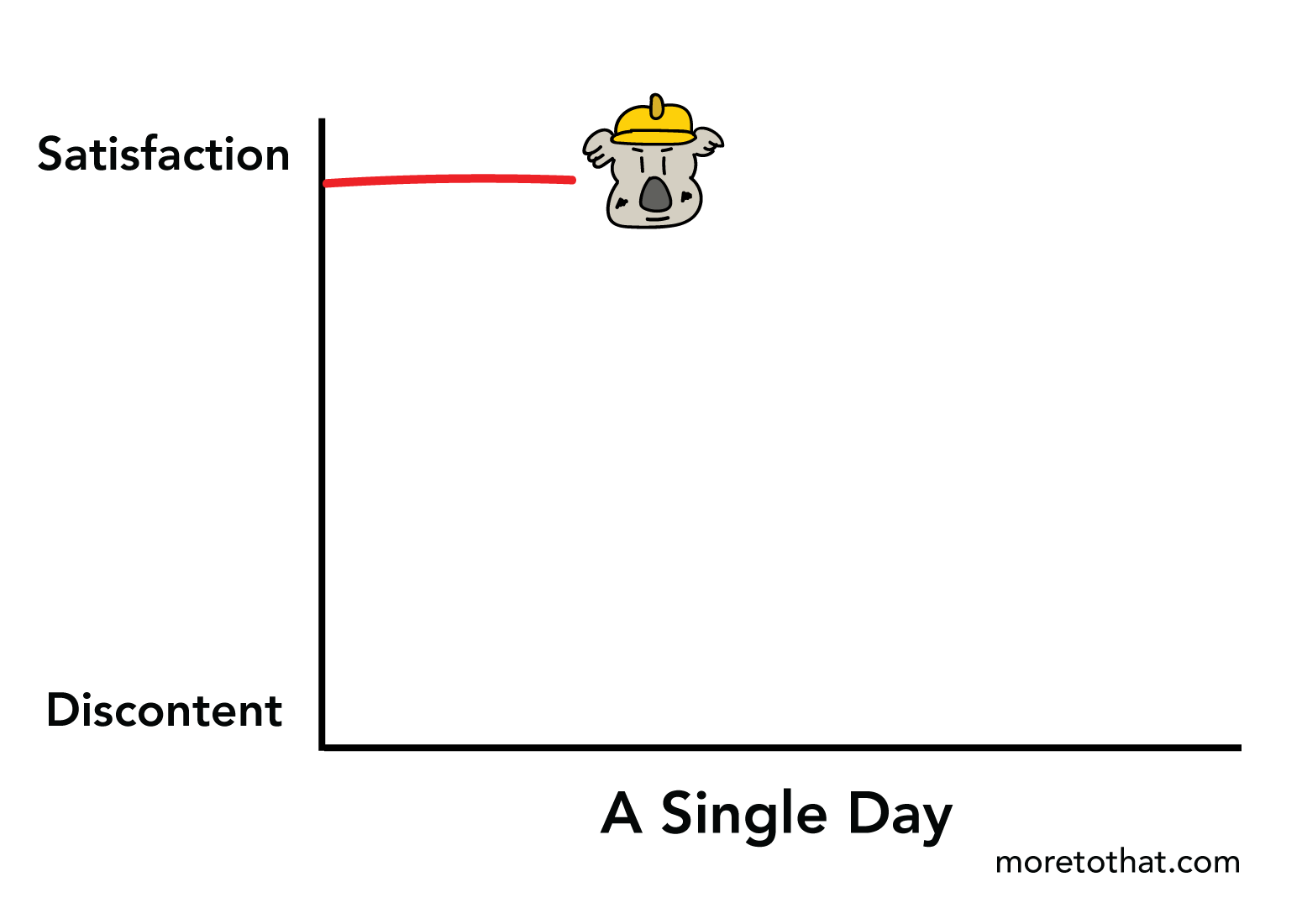

Given this shift, I found my “inspiration-as-a-laborer” position to look like this after a month:

Now, if this line kept going up or simply plateaued, that would be the end of this story. We’d all accept that inspiration should be scheduled, and that we can create it ourselves by showing up each day to do the work.

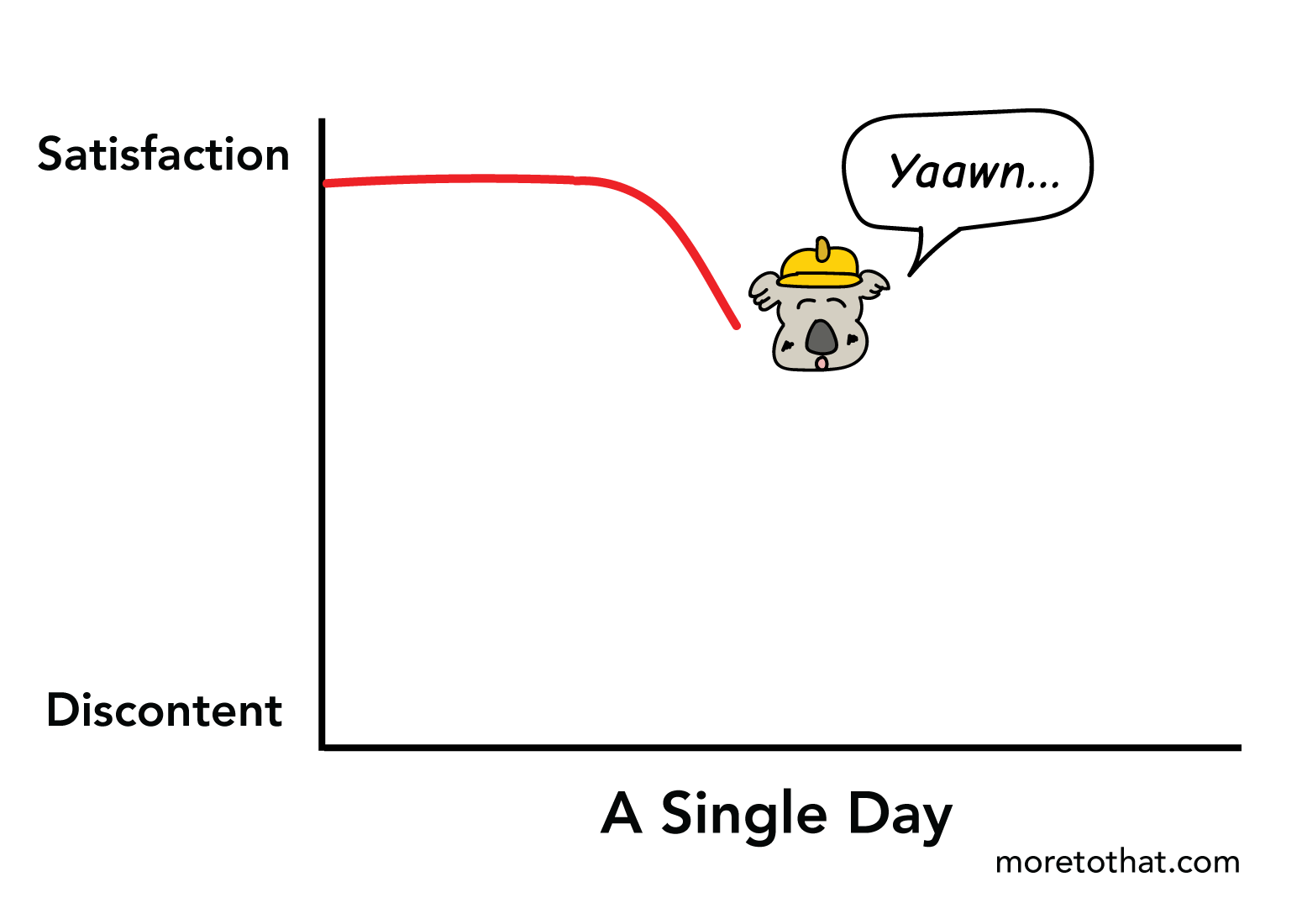

But of course, the passage of time nullifies this trajectory.

As I approached the second month, I began to feel that the laborious view of inspiration was just that… laborious. The line between creating art and manufacturing it was growing blurry, as writing was becoming a clock-in, clock-out phenomenon. Even though I was writing more than ever, much of it was coming from the force of obligation than from the wellspring of inspiration.

Here’s the thing. When you schedule creativity, you develop an expectation of yourself to produce something during that time. It doesn’t have to be good, but there has to be something. The bright side is that you can take the pressure off yourself to create something amazing. The downside, however, is that making something is all that matters, so you stop bringing the best of yourself to each session. In the same way that a hungover employee still makes 100% of his paycheck, a careless creative still fulfills 100% of his duties. As long as he shows up, the job gets done.

This isn’t the writer I aspire to be. I want to enjoy the feeling of writing a piece, and not merely the feeling of having written it. If my creativity is scheduled in advance, then I look forward to the end of it more than I do the start. And since this removes the joy of what it means to create in the first place, it’s only inevitable that you face discontentment after some time.

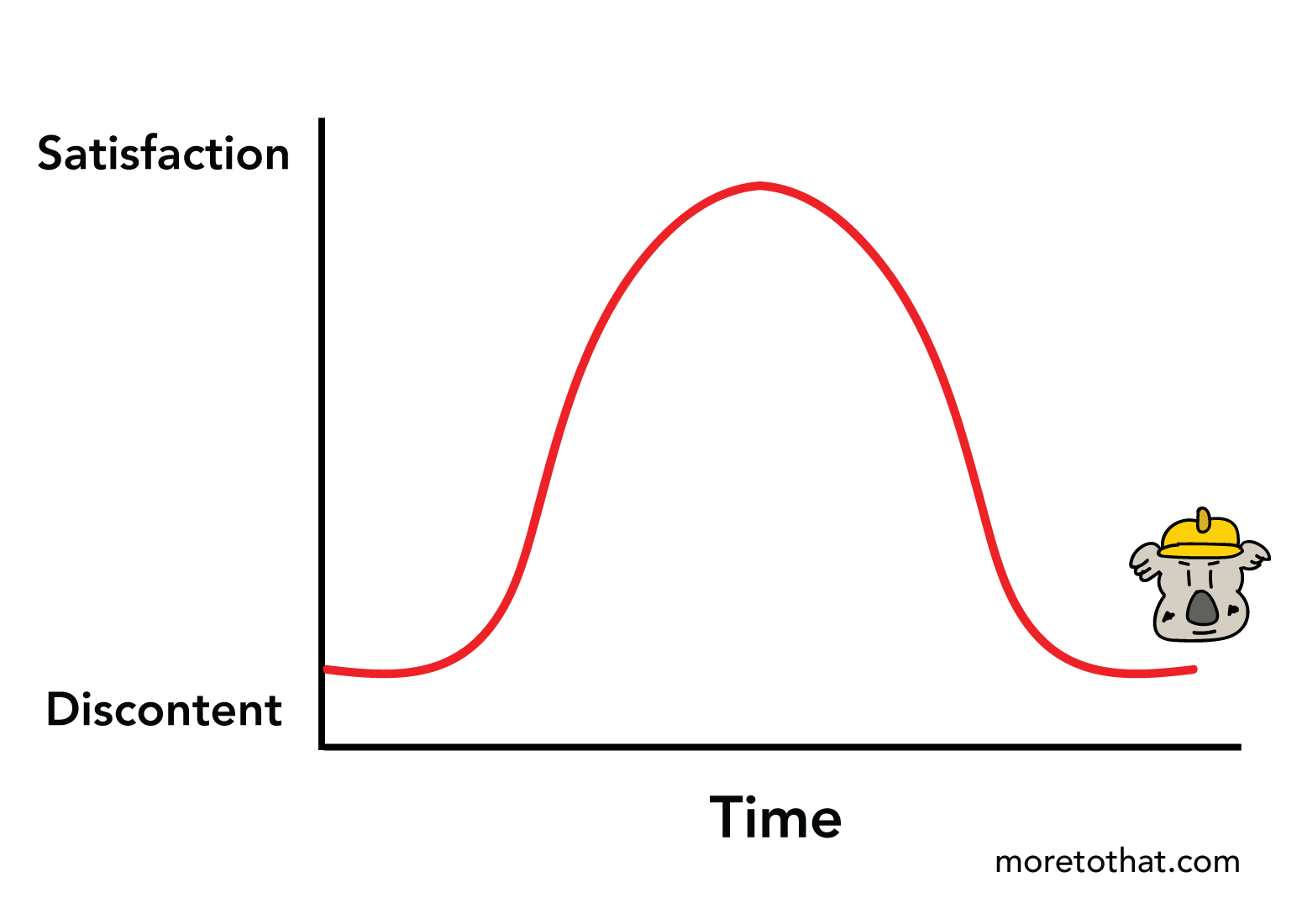

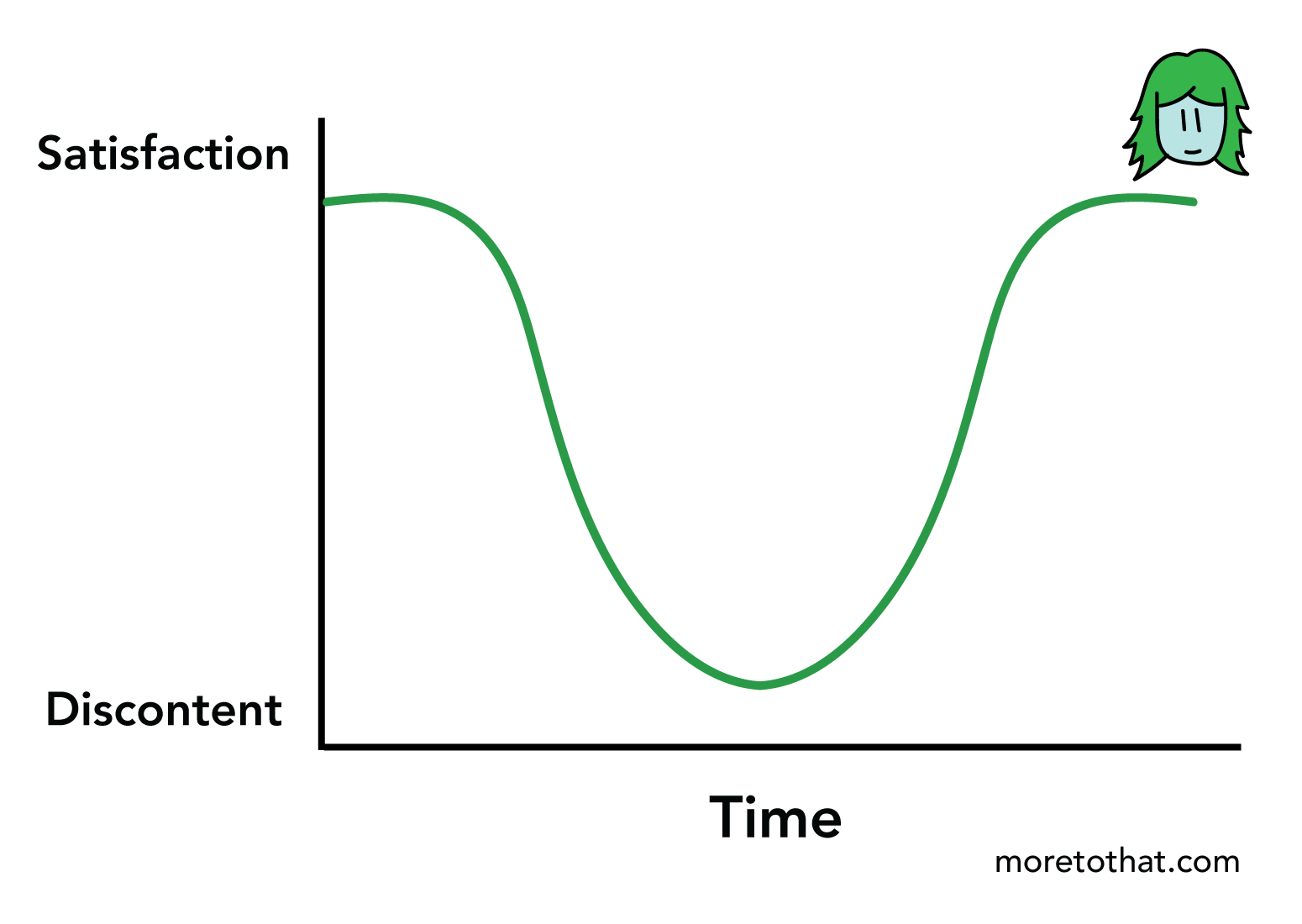

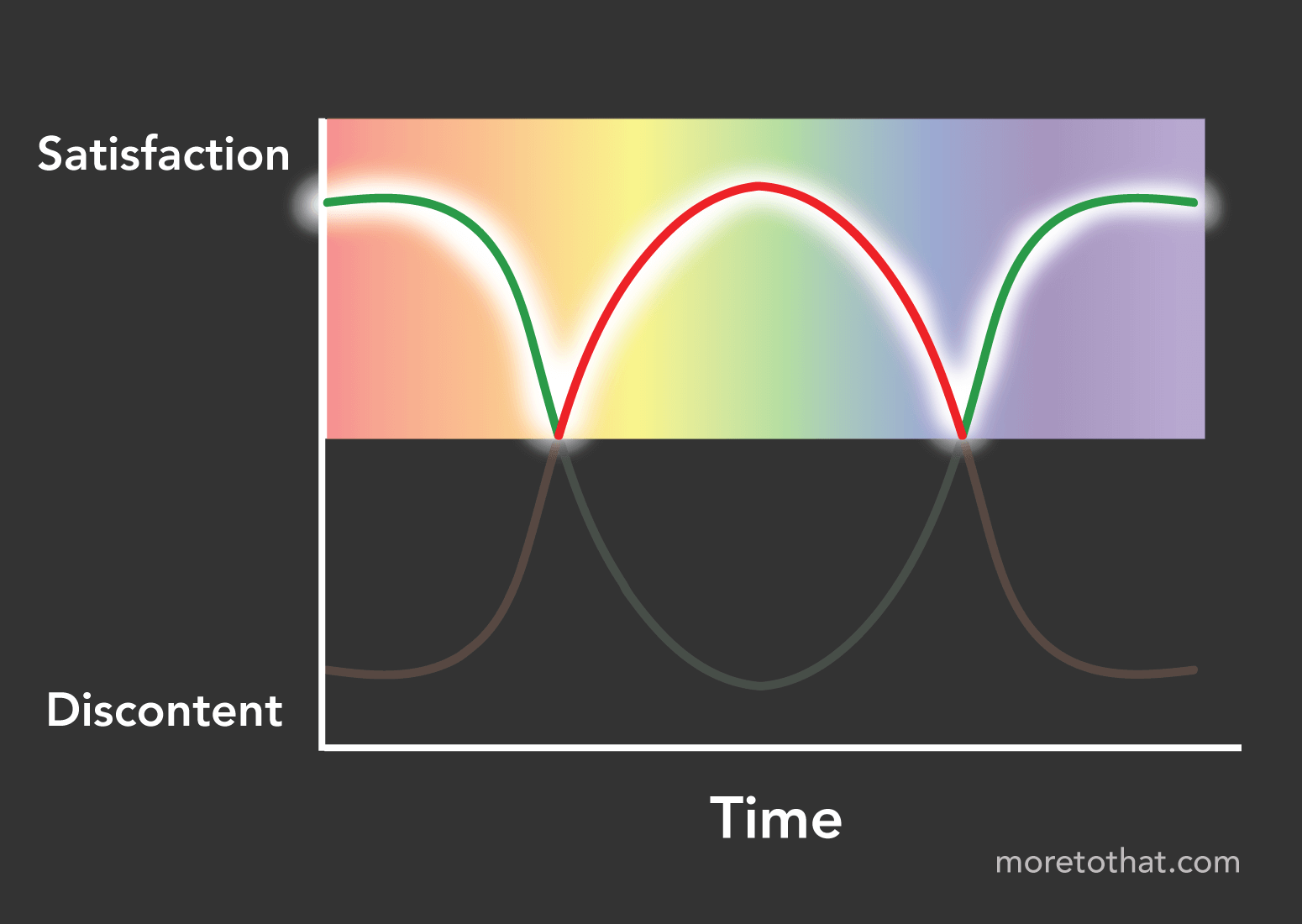

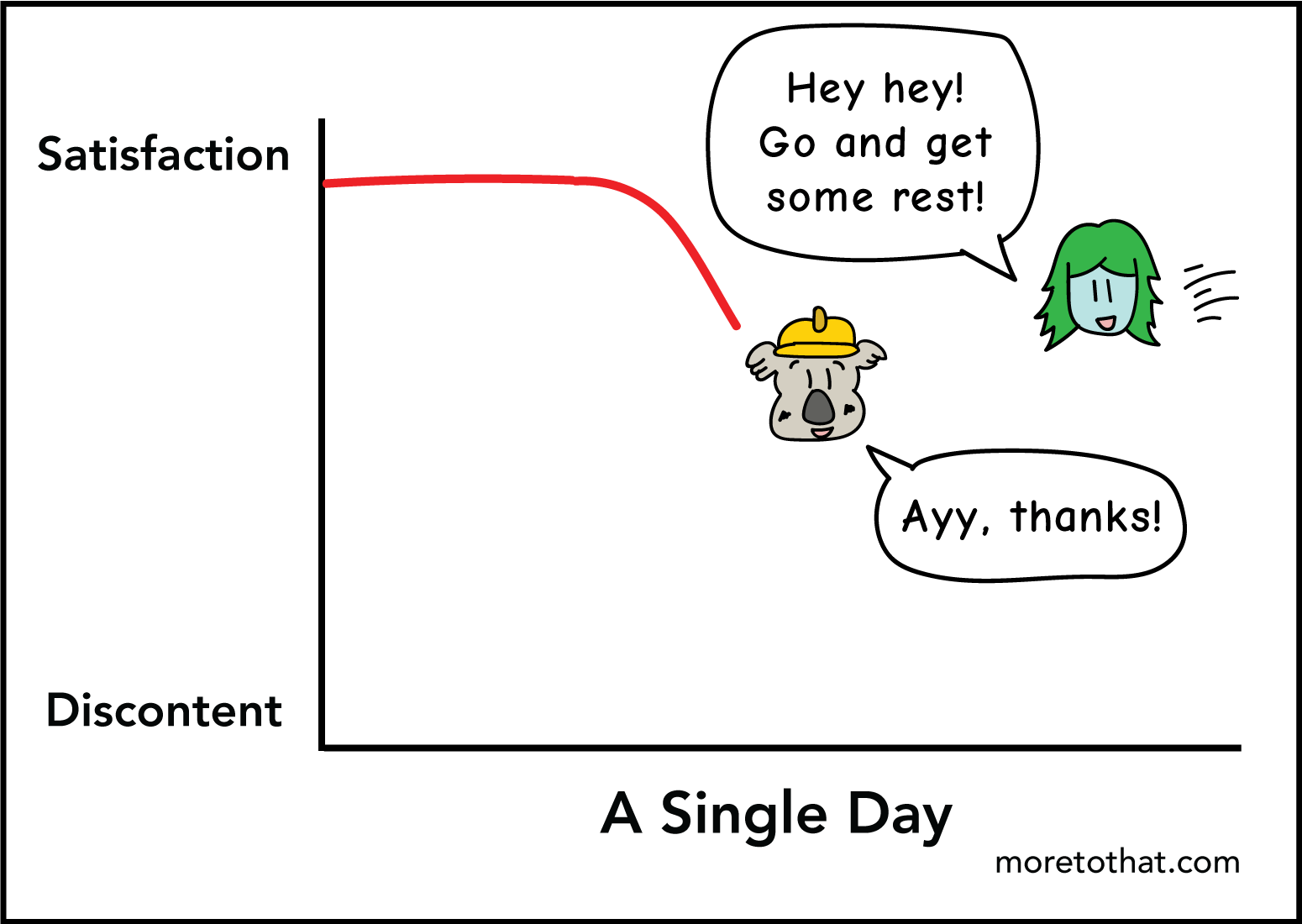

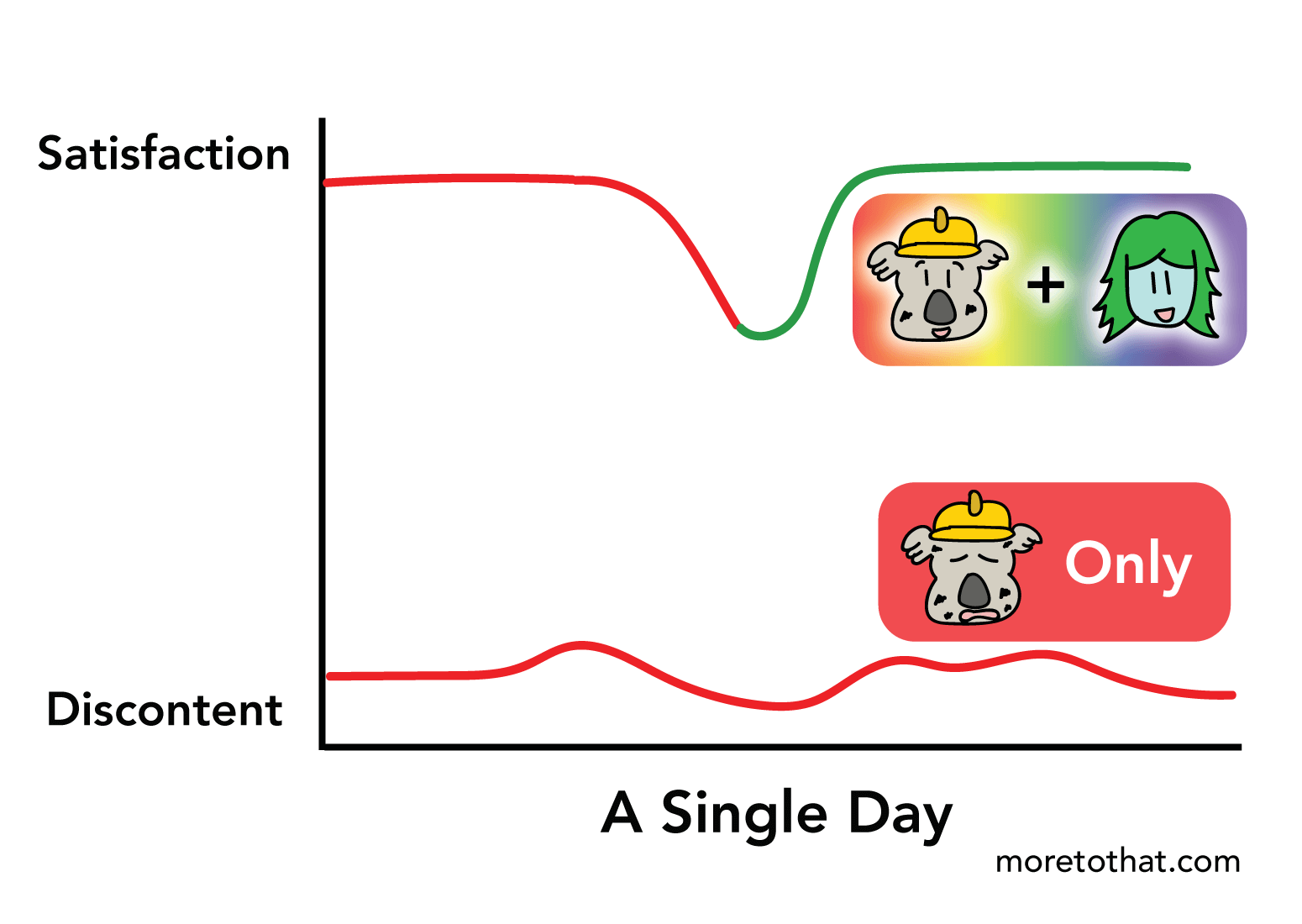

So if this is the inspiration curve that the laborer follows, what about the fairy?

Well, in contrast to the laborer, the start of your creative endeavor will be thrilling as opposed to daunting. The reason is simple: If you start on something only when you feel inspired, then the beginning will always feel energizing. Even if the endeavor seems rather difficult, the presence of the fairy will give you a surplus of motivation that empowers you to take on the challenge.

But of course, anything with a serendipitous nature fades over time. As the days turn to weeks, you’ll find that the fairy doesn’t show up as regularly as it used to, and your hope for its predictable arrival lessens. You start thinking that your well of ideas has run dry, and this translates to less time spent creating and more time spent worrying.

Now, if this is how the curve ends, then we should all dismiss the fleeting nature of inspiration. After all, if it just leads to extended discontentment, then why bother with it? Shouldn’t we just adopt the laborer’s mindset, given that at least we’ll be producing something if we do?

Well, here’s the interesting thing about the fairy: When you’re at your lowest, it tends to come back in full force to rescue you. This is something that can’t be scientifically explained (which makes sense, given that we’re talking about fairies), but this is something we’ve seen time and time again throughout history.

We all know the stereotype of the “tortured artist,” and all the great musicians, painters, and writers that have embodied that phrase. When they felt like they had nothing more to offer, inspiration would somehow strike them to create works that we now deem as classics. Of course, there are many amazing people that don’t need to visit hell to create an artistic heaven, but stereotypes exist because these archetypes are pervasive.

What this reveals is that the fairy does eventually come back, whether its absence tortured you or not. If you do indeed love your craft, there does come a time when your commitment is rewarded through the fairy’s renewed presence. Maybe the conduit was a memorable conversation, a striking book, or even a normal experience that you interpreted as being incredible. Regardless of what it was, you’ll be reminded of what it means to grasp it while you have it.

And if you do, then you’ll experience a fulfillment that feels just as thrilling as the start of it all.

While this sounds like a happy ending, the reality is that the fleeting nature of inspiration is cyclical. If you continue to rely upon the fairy’s whims to get you creating, then you will inevitably enter a dry spell again, and a familiar sense of creative despair will seep in. These spikes of motivation and lulls of discontentment may work for some people, but it probably isn’t the best thing for you. Even though you may get some amazing work during those spikes, the lulls can be debilitating enough for you to quit the whole endeavor entirely, and that’s the last thing we want.

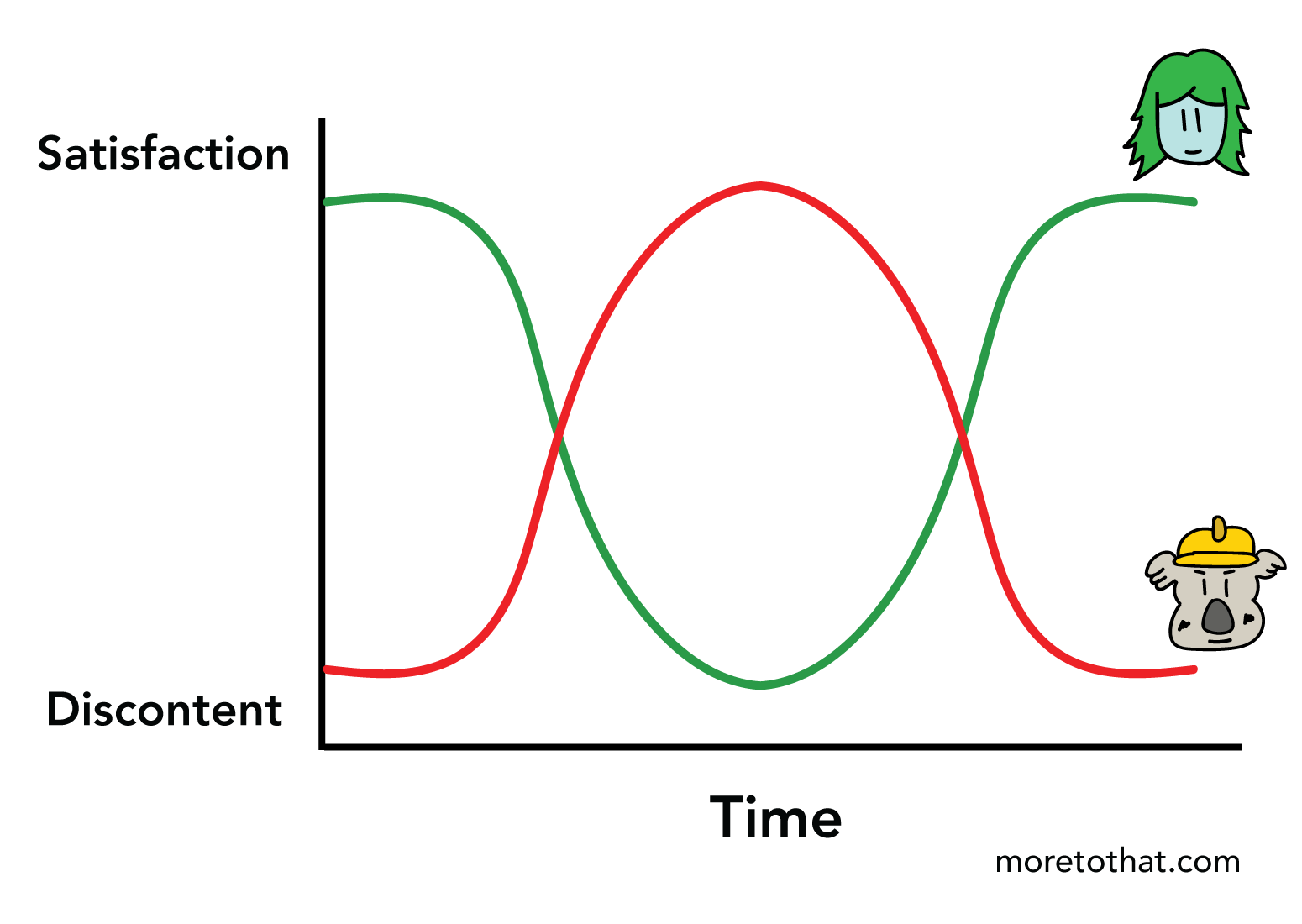

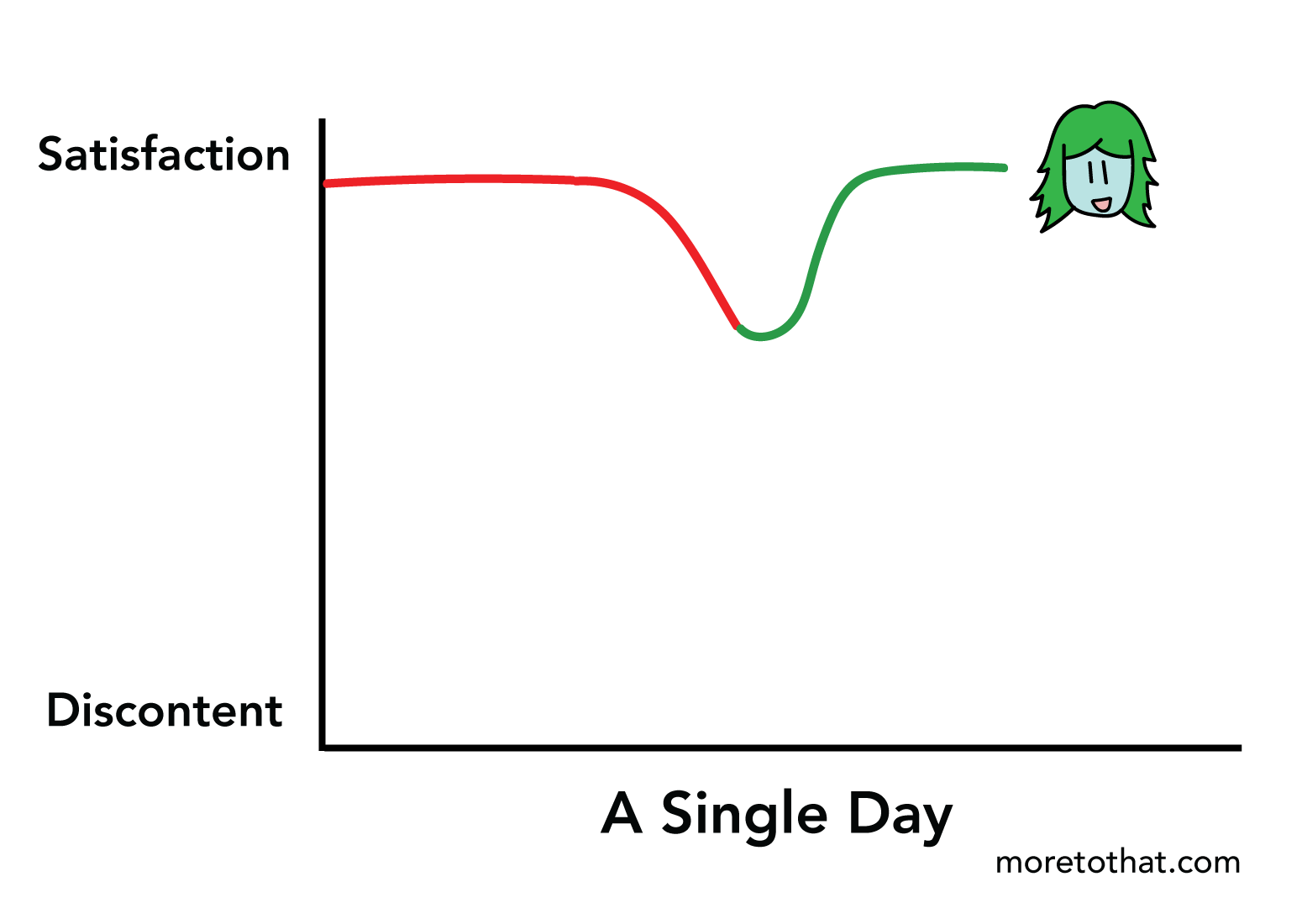

In order to get closer to the ideal balance, let’s first put the two curves together and see what results:

The first thing you’ll notice is that the peak of one curve corresponds to the trough of another. In the beginning, things are exciting for the fairy, while daunting for the laborer. In the middle, a reliance upon the fairy results in disappointment, whereas a commitment to the laborer produces steady work. Toward the end, the fairy provides a jolt of inspiration, while the laborer finds the whole process to be quite tedious. And then, of course, the cycle continues.

What this reveals is that committing to one curve over the other is a losing game, given that there’s always a better option if things go sour. Why be so fixated on regimen and discipline when this will one day make your creative endeavor feel like a monitored job? And conversely, why leave it all up to randomly distributed motivation when you will inevitably face long periods of drought? Why make it one or the other, when you can oscillate between the two?

The goal is to strike a balance between stability and serendipity, and then to import the result into the context of your day-to-day life. You want to remain on the upper half of the graph by transitioning between the two arcs, instead of staunchly staying on one and relying upon time to take you back up.

With that said, the obvious next question is “how”? How do you practically integrate the fairy and the laborer to retain that ideal balance of both?

One of my favorite Dale Carnegie quotes is his instruction to live life in “day-tight compartments.” Instead of viewing life as a vast ocean to wade through, focus on the small island of time that you occupy today. By doing this, you dial down the anxiety that accompanies uncertainty, and dial up the focus that accompanies presence. If the next 24 hours are all that matters, then you’ll be much more attentive to how you spend your time and energy.

This same sentiment can be applied to the domain of inspiration.

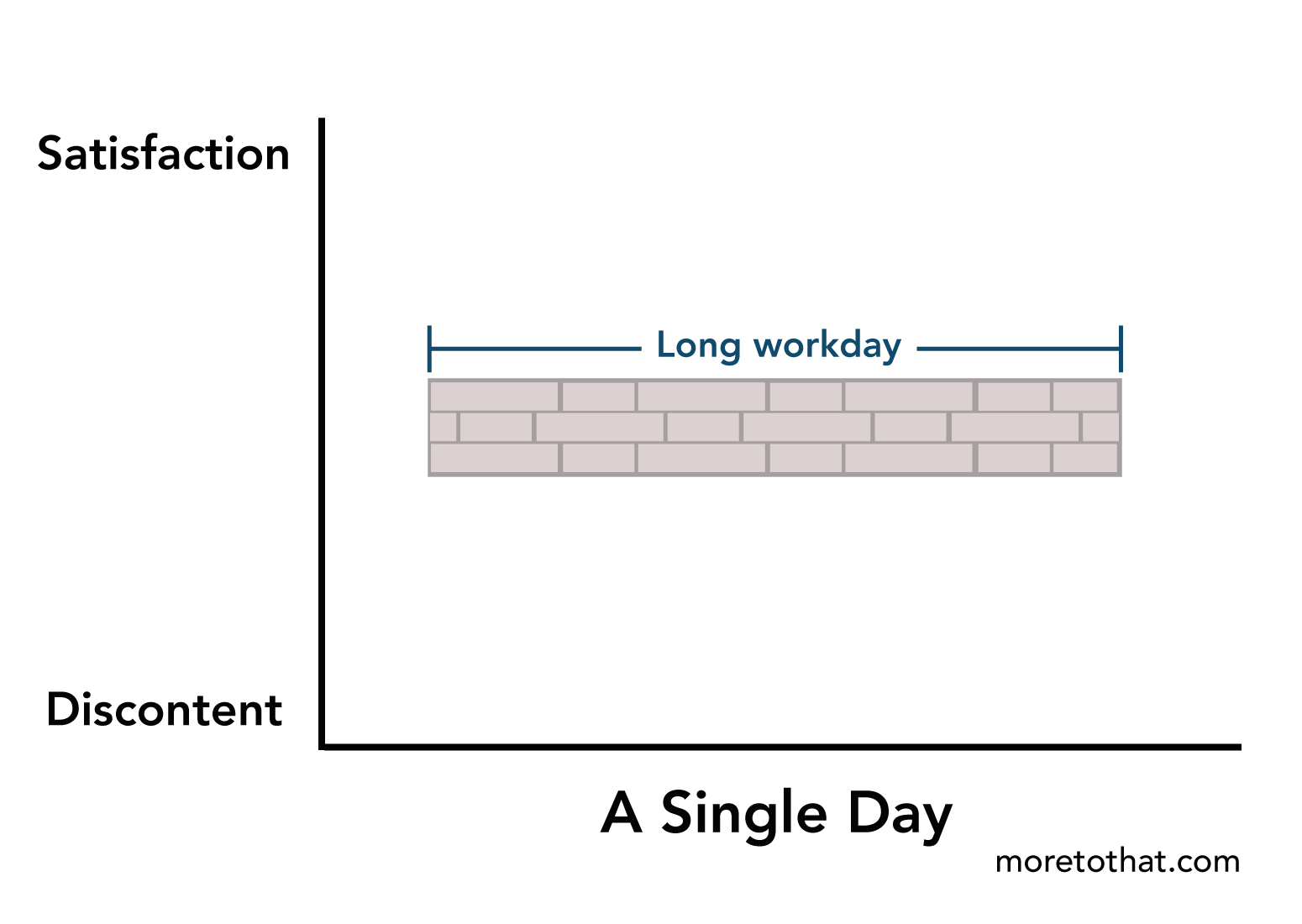

Much of the uncertainty that accompanies creativity is the result of the long time horizon we view it through. We view our artistic growth through the lens of years and decades, not hours and days. While this is a great way to gauge long-term progress, the downside is that each individual day can feel inconsequential. Every block of 24 hours blends into the next, which gives rise to the belief that you have to wait for inspiration’s arrival to introduce an element of novelty.

This only reinforces the caricature of inspiration as a fairy, which inevitably leads to disappointment. So instead of viewing your creative time horizon as this long, drawn-out seasonal affair that is full of uncertainty:

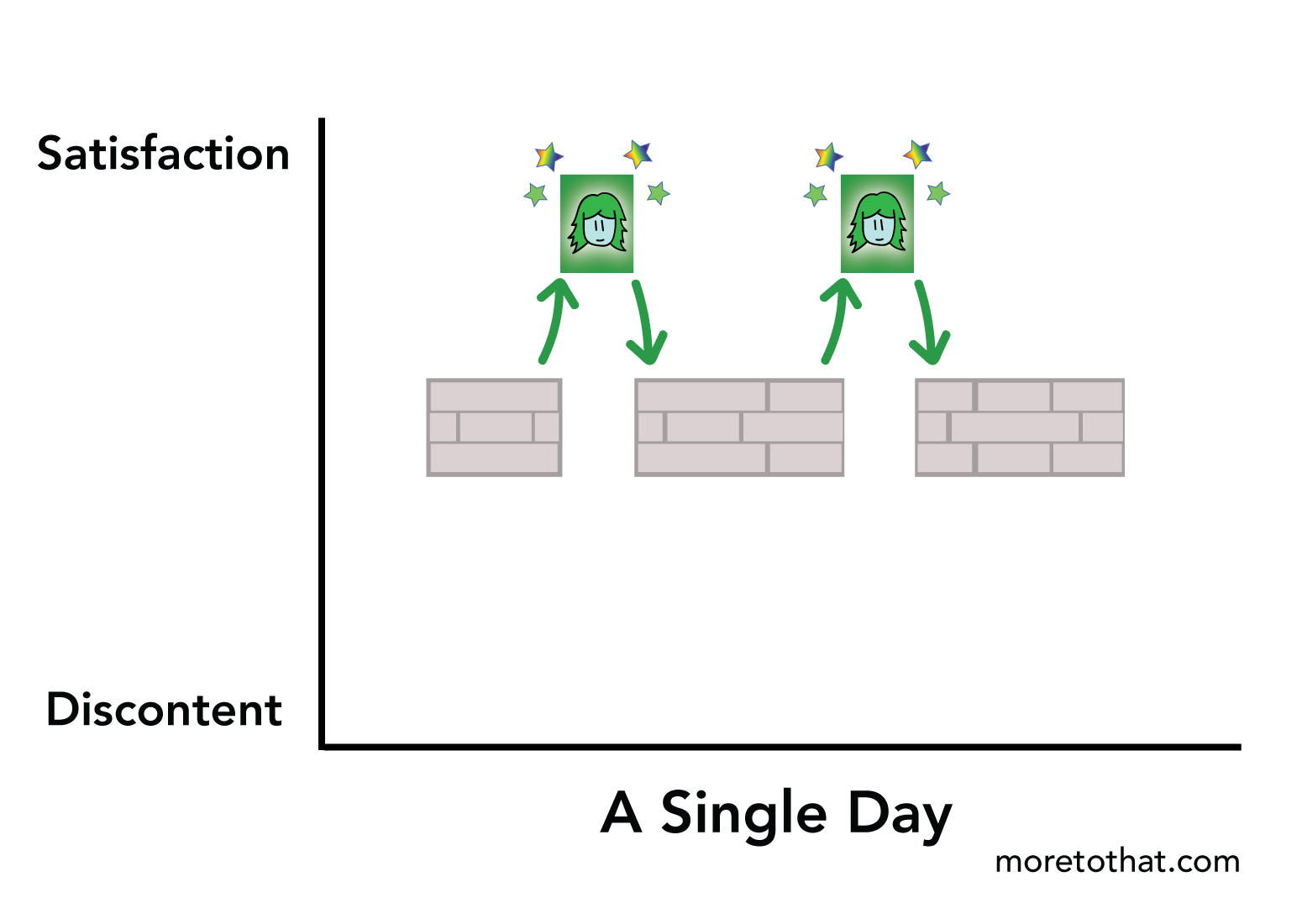

Condense it into a single day-tight compartment that you can direct your full attention toward:

By choosing to view your endeavor through the lens of a single day, two things happen:

(1) You lessen the uncertainty surrounding what you need to work on, and

(2) You can be intentional about how much of the day goes to the laborer, and how much of it goes to the fairy.

Let’s briefly expand upon point #2.

As I said earlier, the best kind of inspiration is a blend of the two archetypes. The problem, however, is that it’s really hard to transition between the two when done in longer time intervals. For example, if you take a regimented, scheduled approach to your creativity for a few years, it becomes a deeply engrained habit. The only way you’ll introduce a serendipitous approach is if you’ve grown dismayed with the laborer mindset, which means that you have to first be dissatisfied with your creative life for quite some time.

The opposite is also true. If you’ve been reliant upon inspiration’s fleeting nature for years, how plausible is it that you can start allocating preset blocks of time to your work, day-in and day-out? That’s far too much conditioning you have to undo, which also applies to the prior example as well.

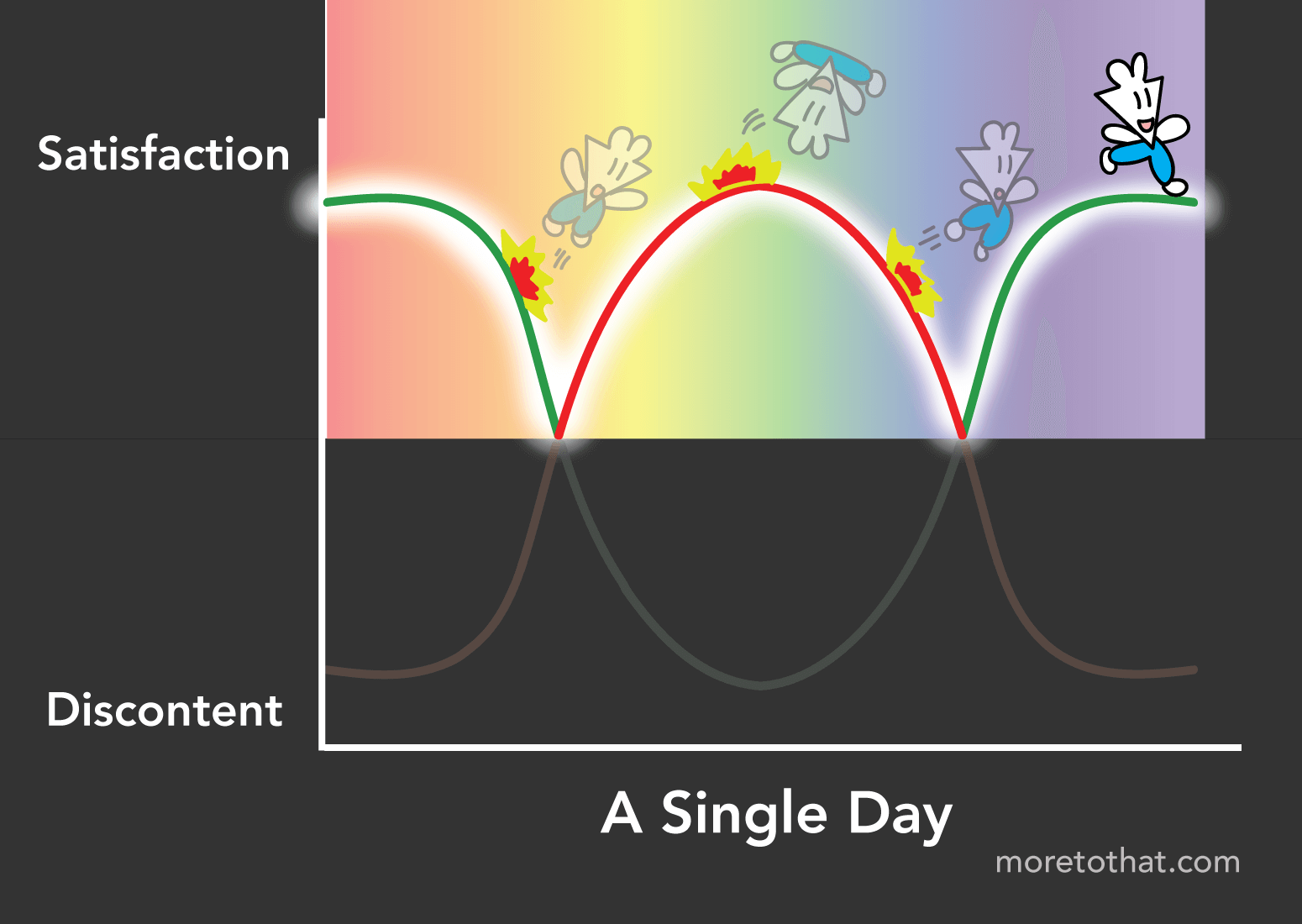

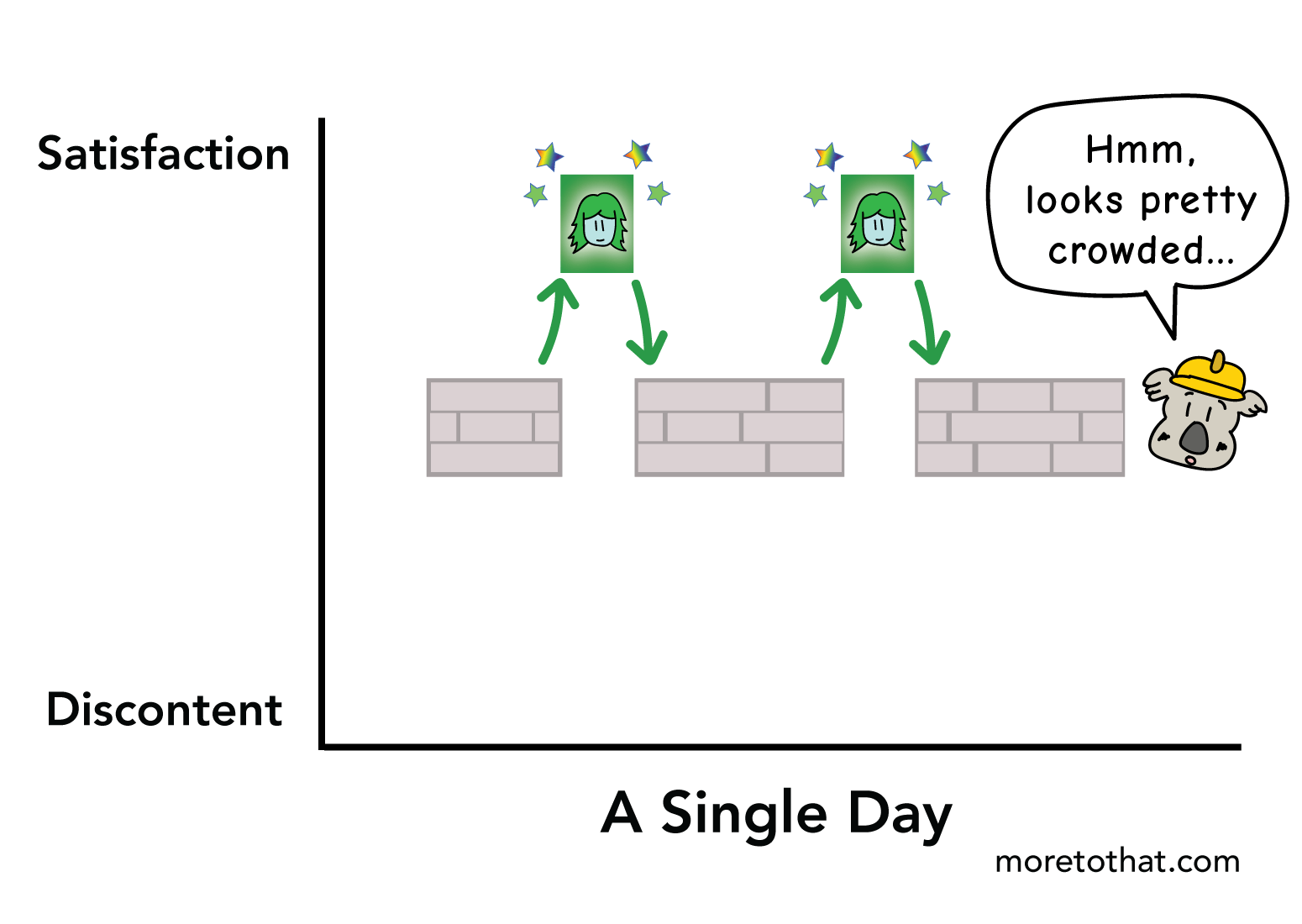

So the key here is to train your mind to accept both forms of inspiration, and to then practice transitioning between the two within a single day. Not months or years, but within a span of 24 hours. Because by practicing this everyday, you refine your ability to fluidly move between the regimented productivity of the laborer, and the artistic spontaneity of the fairy. The border between the two becomes less opaque, which allows you to transition between the respective realms quite easily.

So what exactly does this look like? What does a day with these two characters entail?

Well, the answer will vary depending on who you’re talking to, but I’ll tell you what it looks like for me.

Since my ability to focus is highest in the morning, that’s when I adopt the laborer’s mindset. As a writer, my job is to write, and I don’t want to leave that up to the whims of circumstance. So I generally dedicate about 2 hours of each morning to my writing practice, and I do this even if I don’t feel like I have anything in particular to say.

The reason for this is simple: I write to figure out what I think, and thinking isn’t a pre-planned process. If someone asks you a deep question mid-conversation, you don’t tell them to hold on for a few days while you think through it. No, you simply start talking, and that process of articulation is what ends up informing what you think. Writing is no different from that.

As a laborer, you create your own inspiration, and you do that by showing up and doing the one thing that matters most. In my case, it’s to write. Simple as that.1 So whether I feel like it or not, I set a timer for ~2 hours each weekday morning, and use that time to write. Sometimes I know exactly what I want to think through, and the session is rather straight-forward. Other times, I don’t know what I’m going to say, and the session is more convoluted. But whether the result is good or not, the laborer has done its job, and that fact alone makes your day a productive one.

Now, an ongoing string of this can get tired, burdensome, and make your creativity feel like a job. This is what we depicted on the laborer’s curve where it descended to discontentment. To prevent the monotony that could accompany this, what I’ll then do is switch characters and dedicate the remainder of the day to the fairy. In essence, once the laborer gets his 2 or 3 hours in, he goes to sleep and I open up space for the fairy to come play.

This means that I’ll allow serendipity to be the driving force of what I do. I’ll go for a nice walk, pick up a book I’ve always wanted to read, or play all kinds of silly games with my daughter. This is also the time in which I’ll have conversations with other creators and readers, whether it’s over email, in-person, or video. All of these activities allow me to absorb the world around me, whether materially or energetically. And ultimately, it’s through this blending of experiences that the fairy is given an opportunity to land and provide a spark of inspiration.

This simple ability to transition between the laborer and the fairy is what makes each day disciplined yet fun. Of course, many afternoons are dedicated to doing administrative work and other things that don’t invoke spontaneity, but rarely are they dedicated to writing posts and essays. I make it a point to only do that when the laborer is at the helm, which creates the separation required to prevent the practice from feeling like a never-ending slog. In the end, I probably won’t be as great as the writer who writes for 8 hours each day, but I’ll probably be the happier one.

Now, a common rebuttal to a schedule like mine would be some form of the following:

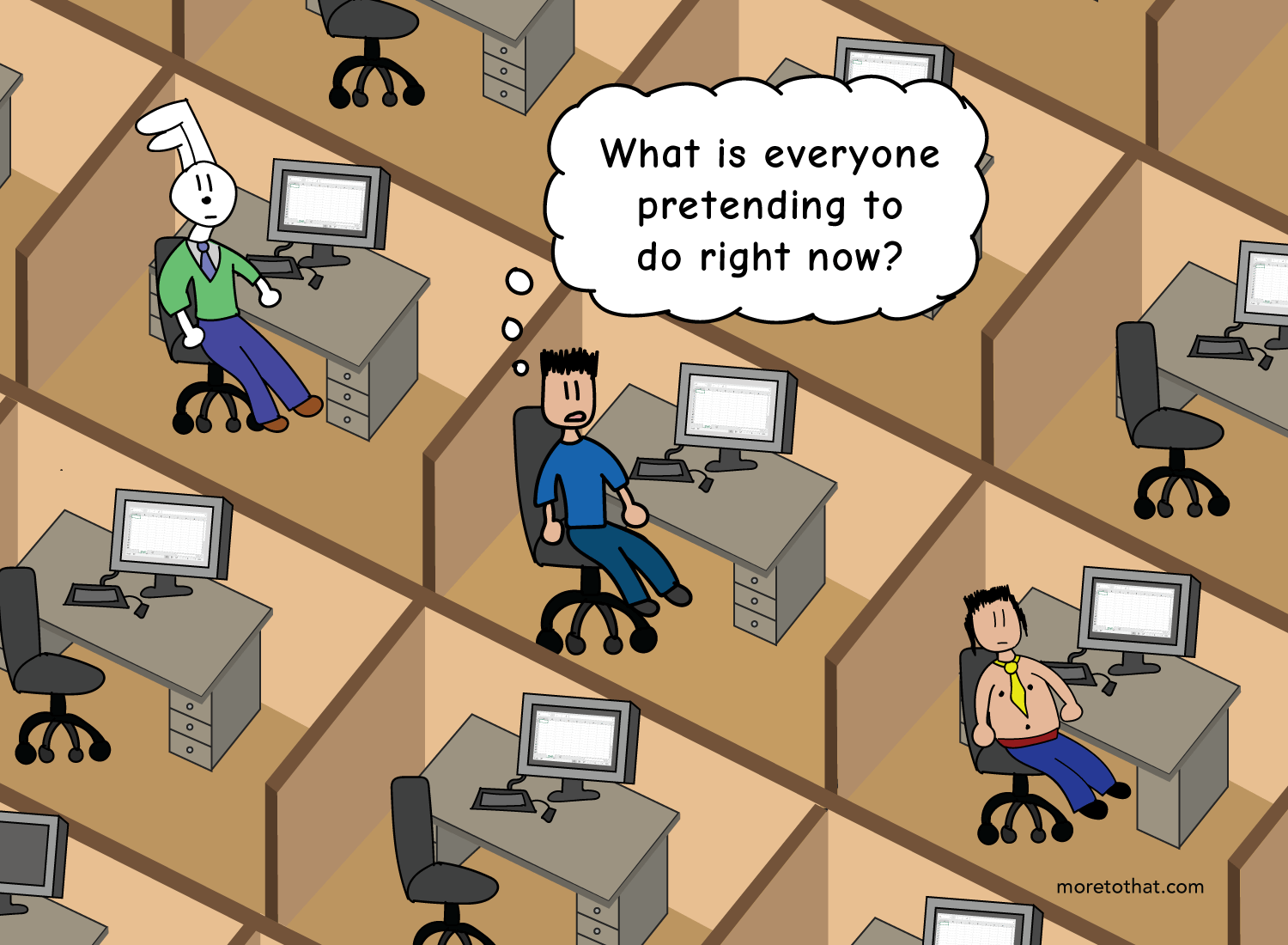

“That sounds great, Lawrence, but that only works if you’re working on your creative endeavor full-time. But what about for someone like me, who works a day job for 8-10 hours each day without much extra time to spare?”

That’s a totally fair point, and I’ll take a moment to answer it.

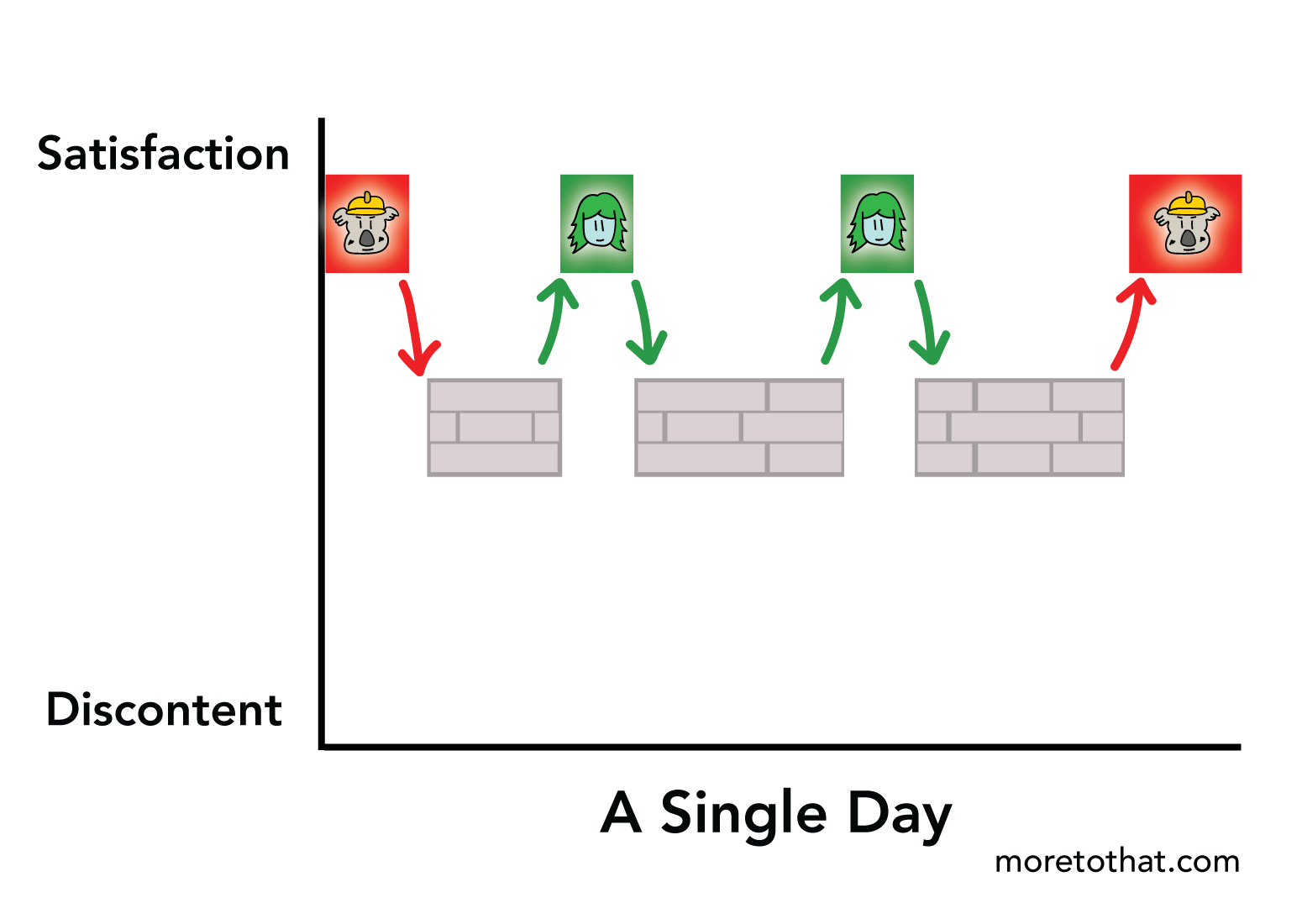

In the above situation, your graph may look something like this, where you spend a big chunk of time in a job that’s intellectually riveting at best, and mind-numbingly boring at worst. (Let’s just take the average of those two situations and put it as a neutral bar below.)

It may be tempting to say that all your time is taken up by this long daunting gray bar, so neither the laborer nor fairy can play here. While that’s a nice excuse, it’s just that. An excuse. I say this not to be mean-spirited, but to reveal any blind spots that may be lurking here.

Here’s the thing. No one works for 8 hours straight on a given task without any breaks or time to re-energize their mind. In fact, it’s rare for even 4 of those hours to be spent relentlessly on the work itself. Usually there’s a lot of idle time, whether you’re throwing it away into the dark hole of bureaucracy or you’re struggling with ways to keep boredom at bay. This was certainly the case for me at all my prior jobs, where I often wondered what charade we were all playing together to create the illusion of busyness.

Regardless of how busy you think you are, you’re not that busy. You can go out for a 20 minute walk if the day is nice, jump on a quick phone call with a friend, or take a break to read that book you’ve always wanted to get to. In other words, there are moments during your workday where you can invite the fairy to roam around and play. Instead of treating your workday like a solid wall of time that can’t be penetrated by any of your creative interests, you can intentionally open up windows of time to allow the seeds of inspiration to be planted.

If you do this regularly, you’ll notice that time isn’t the bottleneck, but the way you use your attention. Instead of checking your work email for the 50th time, you’ll spend it reading something that fulfills your curiosity. Instead of mindlessly scrolling social media during your lunch break, you’ll jot down ideas you want to build upon. This will allow you to regularly absorb inspiration from the outside, which you can then express through discipline from the inside.

So the next question is: How do we incorporate the laborer into all this? After all, he’s the disciplined half that we need for a steady stream of output, but it’s unclear how we’ll fit him in.

While you can open up small pockets of time during your workday for the fairy, it’s hard to do that for the laborer. The laborer requires sustained focus at a specified schedule in order to get the most out of each session, and that’s generally not going to happen while you’re on your employer’s watch.

So instead of squeezing him into your day job, we’ll have to set him outside of it. In other words, the key is to dedicate at least an hour either before or after your workday to sit down and create. The reason I say one hour is because you have to stay on the creative on-ramp for a while before you can hit any semblance of a flow state. Allocating just 30 minutes to the laborer isn’t enough, as it may just be getting its feet warm by the time the session is over. So with that said, the goal is to schedule (at least) an hour-long session at a predetermined time each day, turning it into an effective habit that compounds over time.2

This is how you can incorporate both types of inspiration in a schedule that once seemed implausible to do so.

As you can see, even with that daunting 8-hour block of time allocated to your day job, you can dedicate chunks of time for both the laborer and fairy to occupy. The best part is that it doesn’t require a radical transformation on your end; rather, it just asks for a simple reframing on how to spend your attention, and a commitment to an hour each day.

With that said, it ultimately doesn’t matter what your day looks like, or what your responsibilities may be. Parent or single, day job or not, what transcends any of these limitations on time is your desire to fulfill your latent potential. If you truly believe that there’s something within you that must be expressed, then the next logical step is to test that belief by putting it into action. Potential is not fulfilled by thinking your way through it, but rather by exerting energy into an endeavor that you deem difficult yet meaningful.

Inspiration is the fuel that powers this expenditure of energy, but more importantly, it’s what makes the journey a humanizing one. Creativity without inspiration is devoid of life, and would result in nothing more than functional products designed to serve some selfish goal. It’s only through inspiration where we’re reminded of how connected we all are, as we truly understand how the ideas of one contribute to the worldview of another.

But in the end, perhaps inspiration’s greatest purpose is to reveal that the whole journey can be both rigorous and fun. That you can do the strenuous work required to actualize your potential, while also wander around freely to come into contact with the whimsical. That you don’t have to choose sides between the rational and the magical; that it’s possible to blend both of the two together when traversing this unknown path.

This is what the laborer and the fairy help me to remember. And now that I’ve shared them with you, I hope you’ll keep them in mind throughout your journey as well.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Even if you’re inspired, self-doubt can be a problem. Here’s a post to help you with that:

Perfectionism tends to kill the momentum of inspiration. Here’s a post to help you with that:

As you progress onward, social comparison can rear its ugly head. Here’s a post to help you with that: