Painting the Bullseye: What Happens When We Lose Our Curiosity?

My wife and I recently finished a documentary series called Babies, which explores the first year of life in our favorite kind of human. Each episode focuses on a specific milestone of an infant’s life (such as crawling, walking, etc.), and aims to explain the neurological and psychological mechanisms that drive each of them.

The series as a whole is fairly informative, but there was an odd pattern I was catching with each episode that made it an increasingly frustrating watch. Fortunately, it had nothing to do with the babies (who were all cute bundles of joy – they’re the best), and everything to do with the grown-ups that were being interviewed for the project.

Each episode featured a few neuroscientists that conducted relevant studies in the subject at hand. After a somewhat lengthy introduction of the individual and why he or she became interested in science, the researcher would then go on to talk about the study, and what their initial motivations were for putting the study together.

It is here where the frustrating pattern would emerge.

Consider this statement from a researcher that wanted to study the brain’s influence on crawling:1

“Was the crawling that we saw in the newborn already controlled with something in the brain?”

Or this one about the trajectory of infant height:

“Is [growth] actually continuous, little by little, as we all assume it is?”

Or this one studying parental bonds:

“Does a good relationship between the parent and a baby help the baby cope with stress?”

While these statements sound benign on their surface, there’s a sneaky sleight-of-hand that is being performed with each of them. By framing their reasoning as a “whether or not” scenario, almost all of them already had an expected outcome embedded into the question they wanted to explore. In other words, the study’s hypothesis didn’t just form the inquiry, it also contained the answer they hoped for as well.2

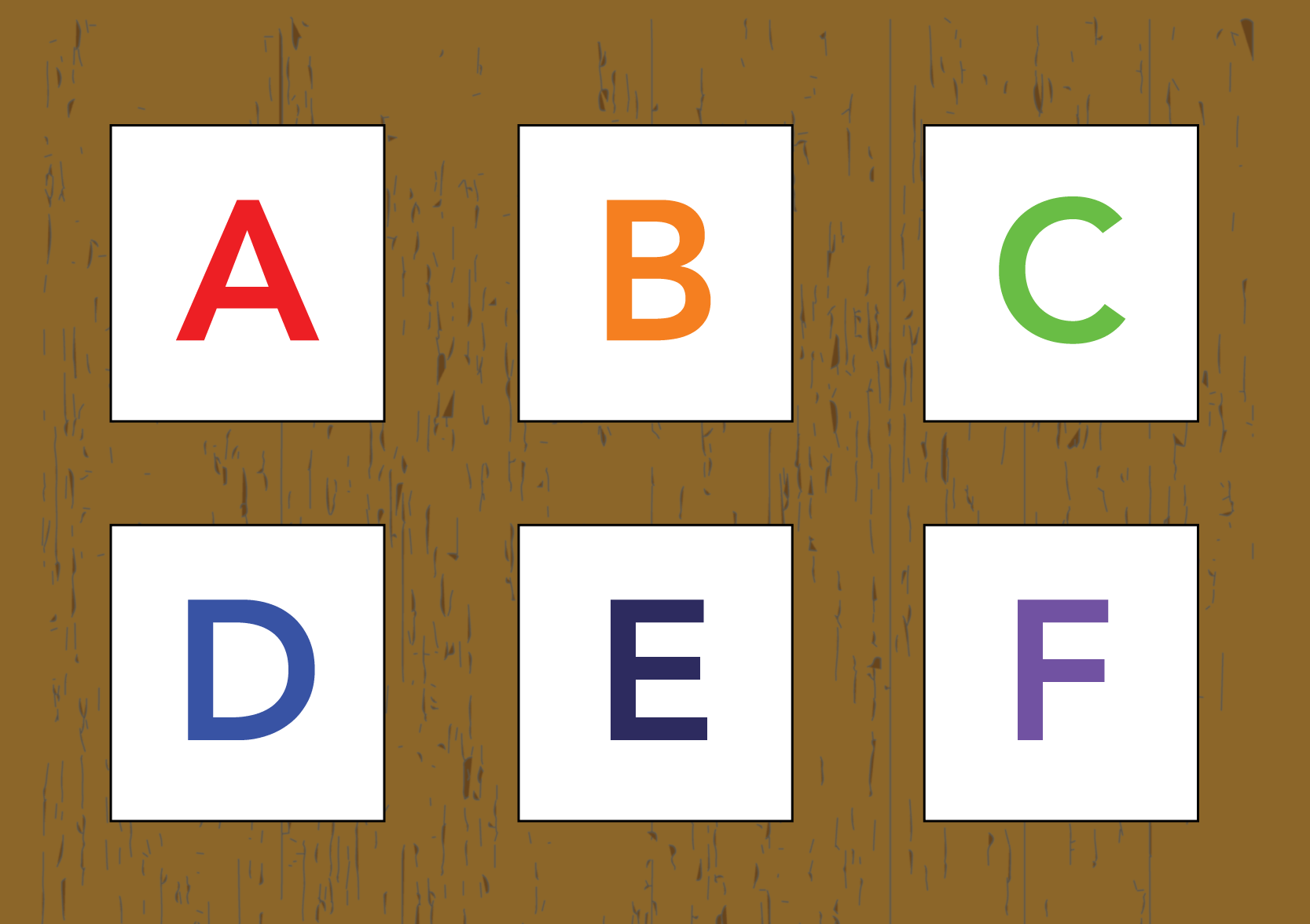

In a truly open-ended, curiosity-driven search for the truth, the breadth of potential answers looks like this:

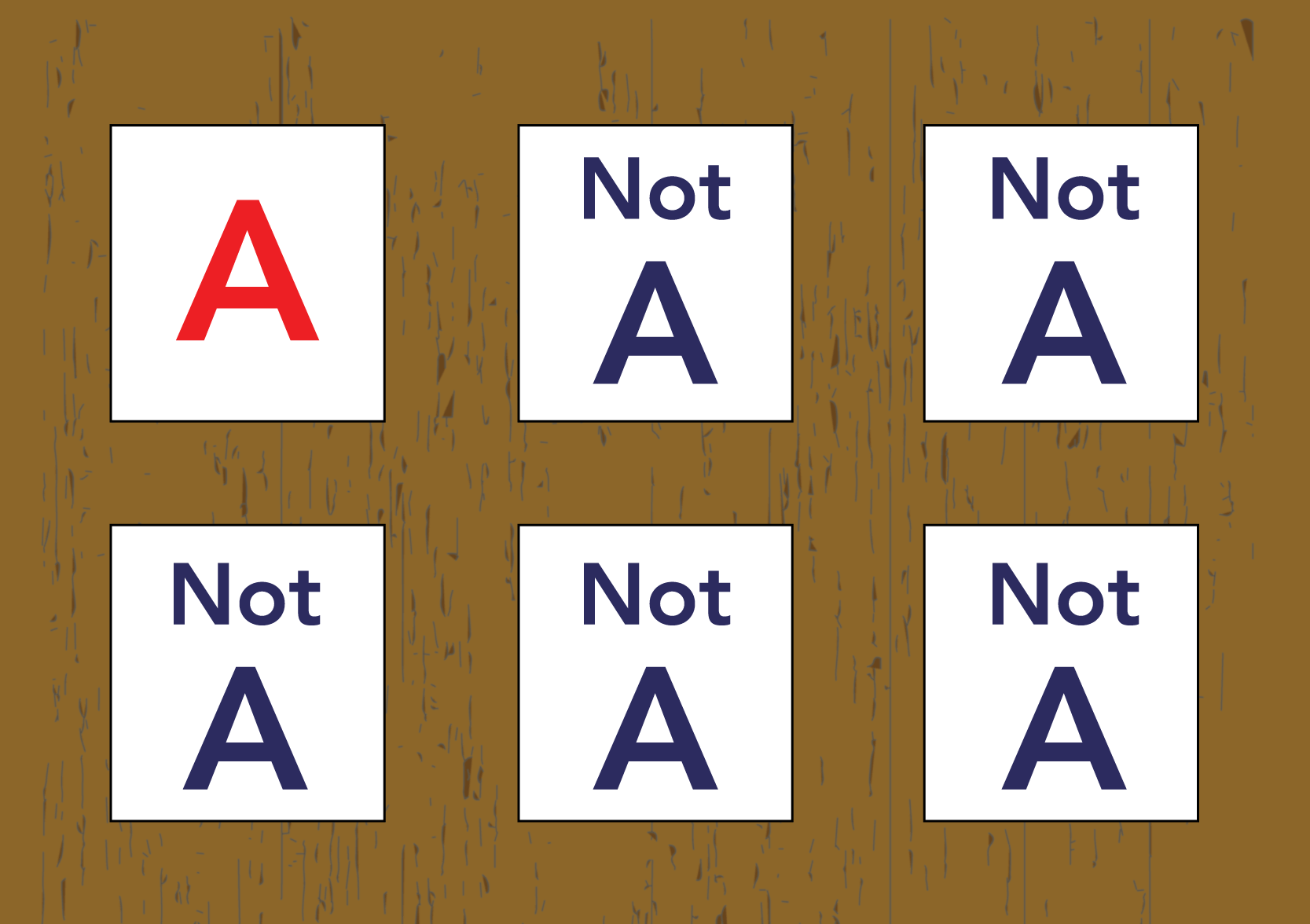

But when you frame your question in the way the above researchers did, your potential answers look like this:

As you can imagine, there will be quite an expectation for “A” to be the answer here.

Framing a search to see “whether or not “A” is true” narrows down the field of exploration so narrowly to that single variable, and that will impact the entire way you structure that search. Environmental conditions will be designed so that “A” is almost guaranteed to emerge as the answer, and everyone is expecting that as well. At one point in the documentary, one of the researchers even says (after a “successful” experiment) that “the fantastic thing about these results was the confirmation of our initial hypothesis.”

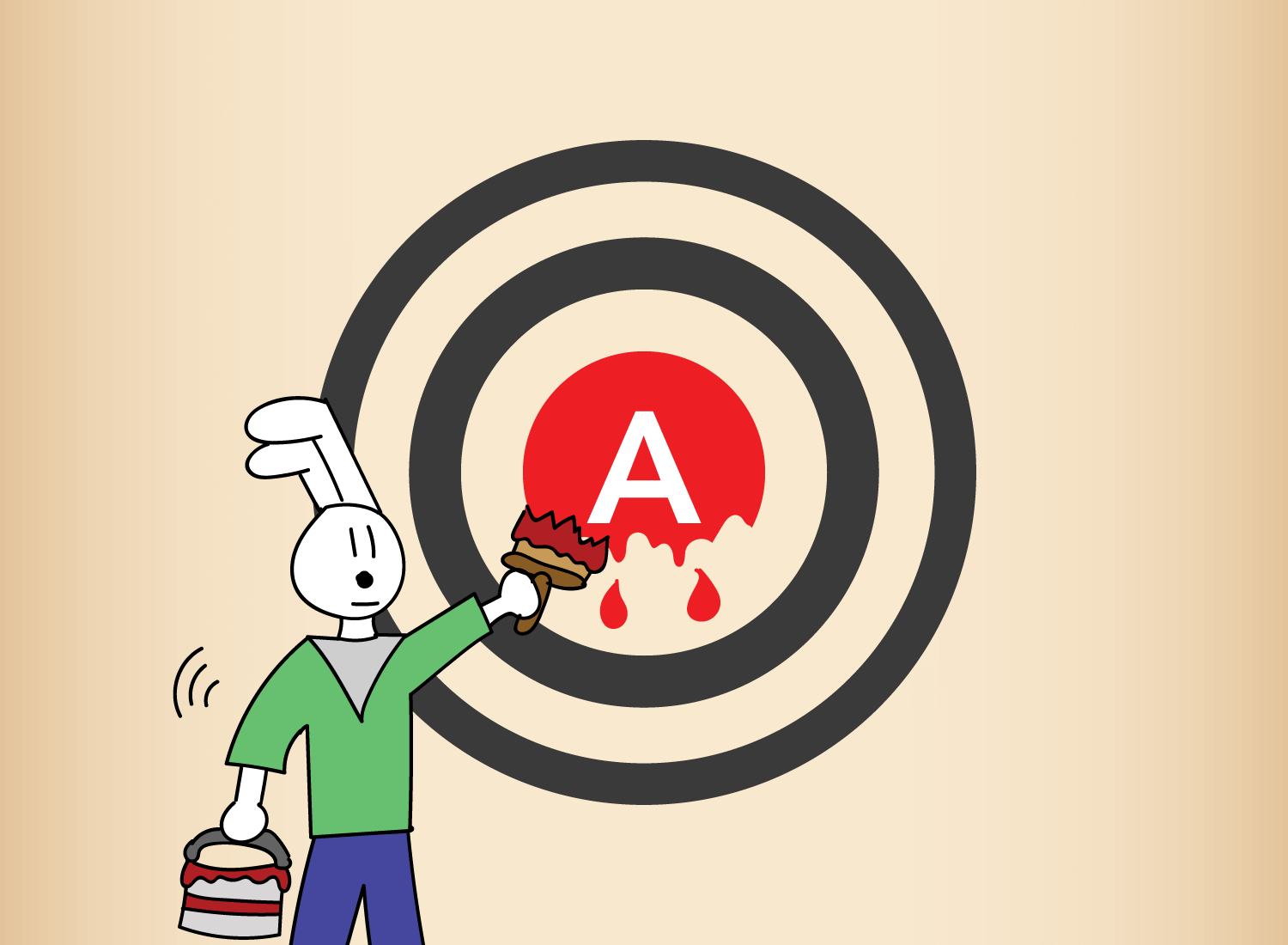

I like to think of this as painting the bullseye before the search for truth even begins. This is when you already have a preferred target in mind, a conclusion that you want your inquiry to eventually reach. If you are depending on “A” to be your answer, then that bright bullseye will be there to remind you of this every step of the way.

This bullseye prioritizes certainty over curiosity; places the destination over the journey. If the conclusion is drawn before the search begins, it’s only inevitable that each step in the middle is guided toward that end. There will perpetually be an invisible wind sending your arrow toward the bullseye; it may drift off-target every now and then, but you sure as hell want it to land properly when all is said and done.

However, I want to be fair here to the researchers in Babies and to the broader scientific community in general. In a sense, this is just the way things work in research. The scientific method is the process of whittling down potential variables to find the most plausible answer, so it’s only inevitable that once open-ended questions like “Why do babies sleep so much?” will eventually be reduced to painting-the-bullseye questions like “Does sleep have a positive impact on infant memory or not?” Once you progress further and have to be more granular with your observations, options naturally become binary as you test what works and what doesn’t.

But the takeaway here is to realize when you’re being hopeful for a targeted outcome, rather than allowing curiosity to be the driving force of the search. If you paint a bullseye beforehand, you’re likely to be disappointed when you don’t hit it, and that introduces all kinds of biases to come and cloud your vision. But if there’s no bullseye to begin with, then you’ll be more open to seeing what other possibilities may emerge as you broaden your field of awareness.

While I used scientific inquiry as the way to introduce the concept, the tendency to paint the bullseye extends well beyond that space, and into one that is far more relatable: the realm of the self.

We paint our own personal bullseyes all the time, whether it’s in selectively reading books that support our beliefs, listening to podcasts that confirm our views, or by joining tribes that are united in certain unshakable values. A lot of the time, we seem to follow a path that is not driven by an openness for the world, but by one that has been determined by an invisible force that is slowly guiding us to the big red dot.

Chances are you know what these already are, and you may be working on overcoming some of the biases that come with having preset destinations. While it’s impossible for me to know what they are individually, there’s one area I want to touch on that appears to be consistent for us all:

The way we paint bullseyes when it comes to connecting with others.

Perhaps life’s greatest paradox is that existence is a single-player game, but meaning is ultimately derived on multiplayer mode. While it’s true that no one will be able to experience your life as viscerally as you can, an inability to share this life with others will largely render these personal experiences meaningless.

The thing we use to construct this meaning is curiosity – a sense of wonderment for the human beings that will become companions in our journeys. When I think of people that exercise curiosity in its purest form, I look to children as the exemplary figures here.

When you see a group of toddlers interact with one another, the desire to connect is not a means to an end – it’s the end itself. Curiosity is not manufactured to signal one’s status or sell some good; curiosity is being exhibited for its own sake, and is the only force that shapes the bonds in that shared space.

The fact that this pure curiosity exists in toddlers alludes to the fact that it is still innate within us today. But the problem now is that we are aware of status games and social hierarchies that add layers of identity to our being. We are no longer just humans. We are analysts, managers, presidents, designers, teachers, churchgoers, doctors, investors, and so on. And the more we attach ourselves to these identities, the more they introduce hidden motives into the reasons why we connect with others.

There are many ways we paint bullseyes when we develop relationships, or ways we set expectations of what we want certain bonds to yield. Some are classic: for example, whenever someone says they’d like to befriend a person that stands atop a social hierarchy they work or operate in, this is a reliable indicator that some type of personal gain is expected through this relationship. They may mask it as curiosity for the other, but underneath it is a targeted desire to be close to what that person’s identity represents.

Other forms are more subtle, and these are the ones that require us to take a moment and examine the nature of our behaviors. It’s usually the small things that act as big windows into our truest selves, and even the smallest bullseyes can motivate our behavior as a whole.

One personal example is apt here. As I writer, I enjoy reaching out to other writers to say hello, and I like developing a sense of community around a craft that can be quite isolating at times. While this has largely been a healthy thing for me, I’ve realized that there can be a tricky dynamic at play here.

Whenever you enjoy, admire, or respect another person’s work, the scope of curiosity is no longer wide open; it tends to be dialed into a specific part of that person’s identity (which in my case, is that person’s identity as a writer). This makes it easy for you to sneakily paint a bullseye that directs your attention to that person’s standing in that realm, rather than the individual as a whole. Instead of curiosity being the attracting force, the desire for status (and a proximity to that) can easily replace it.

Understanding this, I try my best to frame every potential connection through the lens of a toddler. I want curiosity to be my only guide – the end in itself. The only three things I want to understand better are:

(1) Who are you as a human being,

(2) What made you who you are, and

(3) What do you want to be?

If I’m being honest with myself and am certain that these three questions are guiding the nature of a new relationship, then I know that curiosity is at the helm here. There’s no status signaling bullseye that’s been painted, nor is there anything else I’m expecting to extract from this bond. All that’s left is a sense of wonderment for this individual – a feeling of gratitude that comes when you realize how unlikely it was for your life paths to ever cross, yet here you both are, holding space together in this brief moment of time.

Expectations are a normal part of existence, as they help us identify and align our personal goals within a realm of infinite possibilities. However, while it’s important to understand their utility, it’s just as crucial to be aware of how they can misguide our view of the world.

In front of each of us is a material reality that is so unfathomably complicated, a reality we are trying to better understand each day with exploration and experimentation. But within each of us is an equally complicated reality, one we are trying to better understand each day with the sharing of stories and the intertwining of narratives.

Both realms are riddled with uncertainty, and sometimes it may feel comforting to paint bullseyes and target outcomes so we can have some semblance of predictability. But when we take a moment to look deeper, what we’ll find is that the things we don’t know are ultimately what make life such an interesting journey. And since curiosity is nothing more than being grateful for the unknown, it is the only light that can guide us through a world we will never fully understand.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Here’s a way to see which of your beliefs have been painted by bullseyes:

Do You Really Believe What You Believe?

Our memories are also riddled with them:

Memory Is the Shadow of Fact, the Artifact of Feeling

To read about an exemplary grown-up that chose curiosity over certainty: