Socrates: The Badass Godfather of Uncertainty

My favorite hip hop group of all-time is the Wu-Tang Clan, and these are, without a doubt, the best opening lines they’ve ever recorded:

“I bomb atomically, Socrates’ philosophies and hypotheses /

Can’t define how I be droppin’ these mockeries.

Lyrically perform armed robbery,

Flee with the lottery, possibly they spotted me.”

This is from the first verse on their classic song, “Triumph,” and the man responsible for this masterpiece is Inspectah Deck.

I find it amazing that one of the most revered hip hop groups, in one of its most famous opening lines, has a reference to an old Greek philosopher that roamed the earth 2,300 years ago. This just shows you how influential of a figure Socrates was, and continues to be today. From undergraduate philosophy papers at Stanford to underground rap lyrics in Staten Island, Socrates’ name is a synonym for clear thought and rationality, two ideals that have shaped the modern world.

Although Socrates is a name we’ve all heard in some shape or form, he’s probably a guy that many of us don’t know enough about. That was certainly me up until a few weeks ago, so I wanted to explore two questions about him in this post:

(1) Who exactly was this guy, and

(2) Why the hell should we care?

Those are very valid questions, and I’d like to get through them both. Let’s start with #1.

What Socrates Was Like

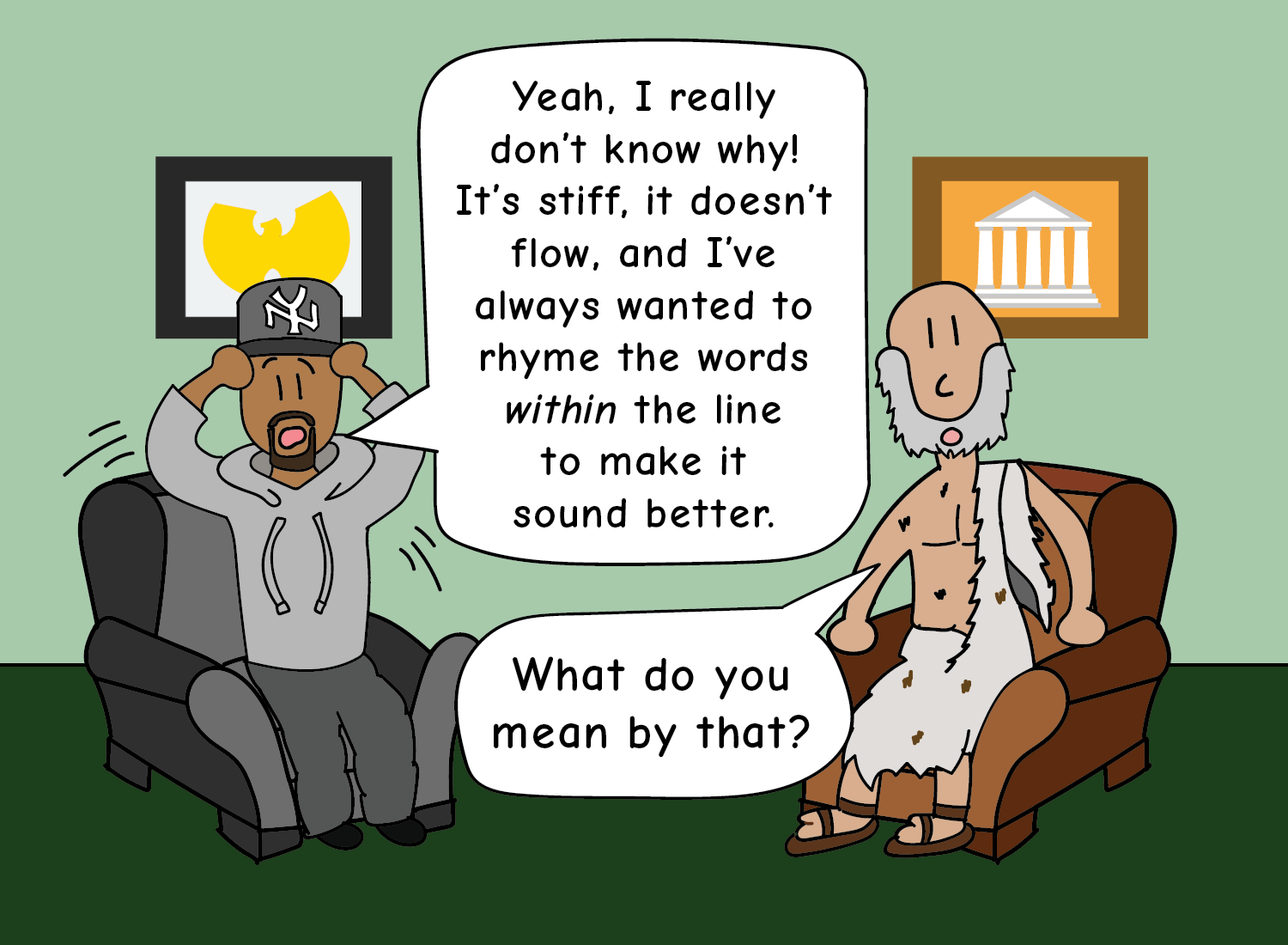

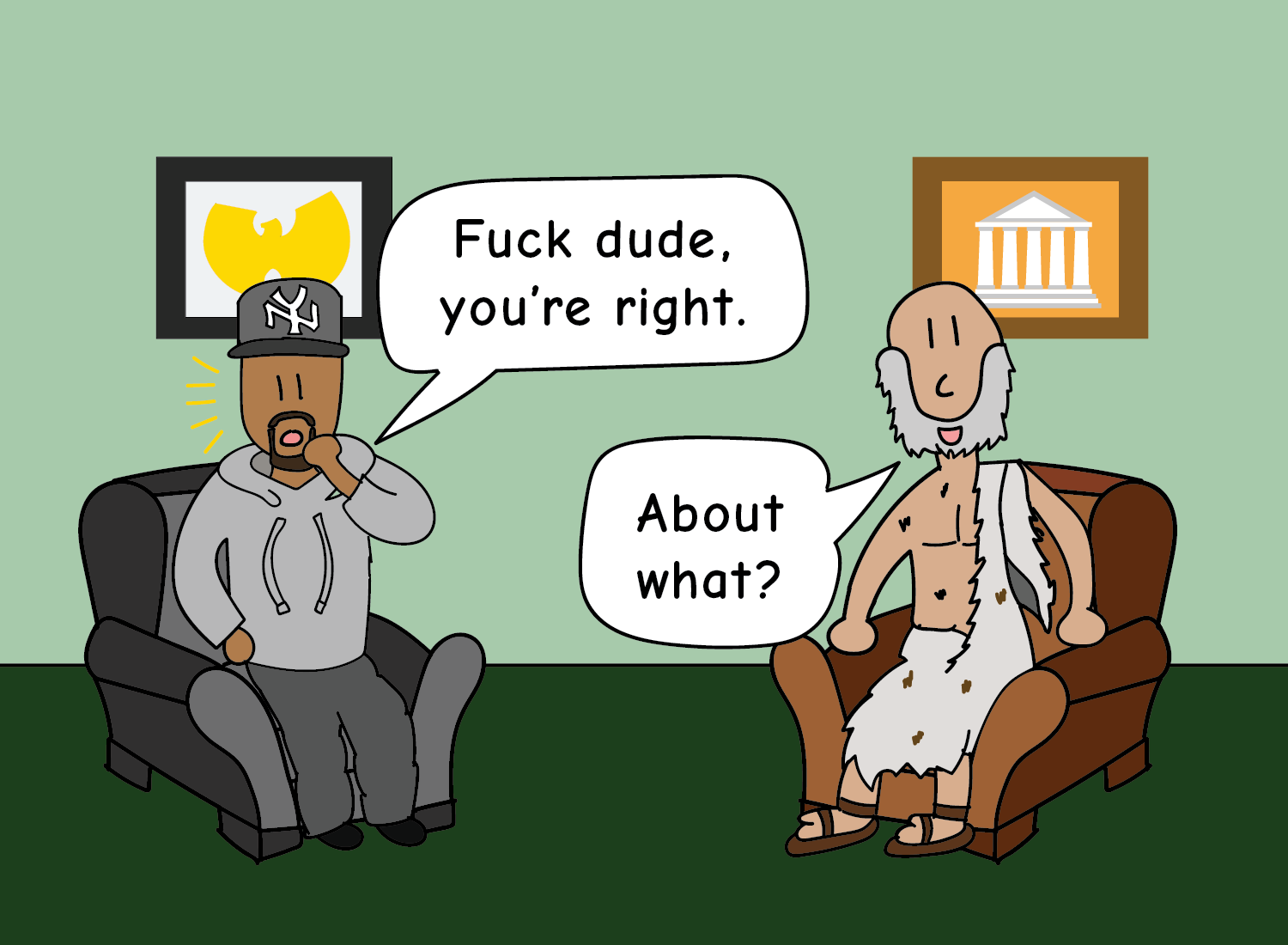

Let’s say we put Socrates in a time machine and brought him to meet Inspectah Deck.

The first thing Inspectah Deck would notice was that Socrates, the brilliant man he honored in his opening line of “Triumph,” looked homeless as fuck.

Socrates was smelly, never bathed, never worked, and wasn’t that great of a husband too. He rarely knew where his next meal would come from, and was known to roam the streets of Athens in the fifth century BC, debating people and pissing them off in the process. He might simply be known as a “hipster” today, but back then, he was probably just homeless.

Despite this, Socrates had his share of loyal disciples and students, many of whom were brilliant and created legacies of their own. One of these people was Plato, who went on to become one of the most influential philosophers of the Western world. In fact, if it weren’t for Plato, we probably would have known nothing about Socrates in the first place.1

To understand how someone like Plato could be a student of an unkempt, wandering man like Socrates, it’s important to understand what the intellectual landscape of Athens looked like at the time, and how Socrates threw a wrench in the whole system.

Sophists: The Masters of “Woo-Woo”

In the fifth century BC, the Athenian government pushed away from historical warrior values, and into more democratic ones. Physically beating the living shit out of your opponent was no longer a signal of influence; it was more about how you used your words to persuade others to join your cause.

This shift toward democracy allowed matters of law to thrive, and lawsuits became the primary tool people used to get what they wanted. The problem for most people, however, was that rhetorical self-defense was a new development at the time. People didn’t understand how to use words to prevent themselves from financial ruin (or even worse, from being sentenced to death), so many Athenians found themselves on the wrong side of justice, simply because they weren’t good at articulating their positions and thoughts.

Additionally, as democracy became the preferred form of government, one’s political success was directly tied to his public speaking abilities. A vote-by-majority system required politicians to be well-spoken and persuasive in their arguments; if you were smart but had the charisma of a potato, no one would vote for you.

The combination of these two factors created a market for a group of philosopher teachers known as the Sophists. For a hefty fee, the Sophists would teach people how to articulate their thoughts and become better public speakers. While this sounds helpful, their philosophy and approaches to using rhetoric in this way were pretty shaky.

First, Sophists believed that the spoken word was a tool of persuasion, and not about getting to the truth. It was about using your words to sound smart and wise, instead of painting a careful picture of reality.

A modern-day equivalent of a Sophist might be one of those “woo-woo” spiritual teachers you find at a mystic retreat (or for a more public figure, perhaps someone like Deepak Chopra). They may be putting a lot of interesting words together to sound compelling, but they’re just creating an incoherent word salad that isn’t saying much.

On the other end might be a prominent lawyer that actually constructs coherent arguments, but for a morally detestable purpose. This would be a lawyer that helps exonerate known murderers through persuasive arguments, and helps other terrible people evade the reaches of the law.

Sophists understood the power of language, but used it in a way that only benefited the one who spoke. It wasn’t about building a better community and fostering moral values; it was about helping the individual advance his own selfish desires through the spoken word.

Second, Sophists were getting filthy rich off teaching people this craft. Instead of viewing wisdom as a publicly distributed good, they viewed it as something that could be monetized and sold for personal gain. This made them quite unpopular in the eyes of the public, and for pretty good reason.

And finally, the underlying philosophy that grounded their beliefs was pretty dubious. Sophists believed that there was no such thing as absolute truth, and that there were always multiple truths in any given situation. Instead of a battle of facts, it always came down to who was more persuasive, and that the better argument would be more representative of the actual truth.

To see this play out, let’s say there was a thief who stole $1,000 from you:

The Sophist could argue that there were two truths at work here. You were personally harmed by this thief stealing your money, but at the same time, the thief may have needed that $1,000 to pay for a medical treatment. Both scenarios are true, but the Sophist might say, “Well, how can we condemn the thief’s actions, given that they provided a crucial benefit for him? Who are we to define what ‘good’ is, given that everyone’s experience of it is different?”

Unsurprisingly, this type of relativism (the idea that there are no absolute truths) aligned well with how the Sophists made their money. If there was no such thing as absolute truth, then it was up to your persuasion skills to convince people of what was “more true.” Truth existed along a spectrum, and everyone was already on it. It was just about how you used your words to bring more people on your side of the truth.

Of course, this then begs the question: if everyone is always right, and everything we think is true, then how can any one person be wiser than the other?

In a world without absolute truth, it becomes impossible to assert that someone is right, and someone is wrong. There are no experts, and there is no wisdom to seek (since everyone is just as wise as their neighbor). We already know what truth is; it’s just our responsibility to persuade others to believe it. This was the Sophist way of thought, and one that was quite prevalent among Athenian thinkers at the time.

Socrates, our protagonist philosopher, observed this behavior and saw so many problems with it. In his effort to search for the truth, he developed a method of reasoning that changed the course of philosophy. It’s called the Socratic Method, and while it might seem like common sense today, it was anything but that in the fifth century BC.

Wu-Tang and the Socratic Method

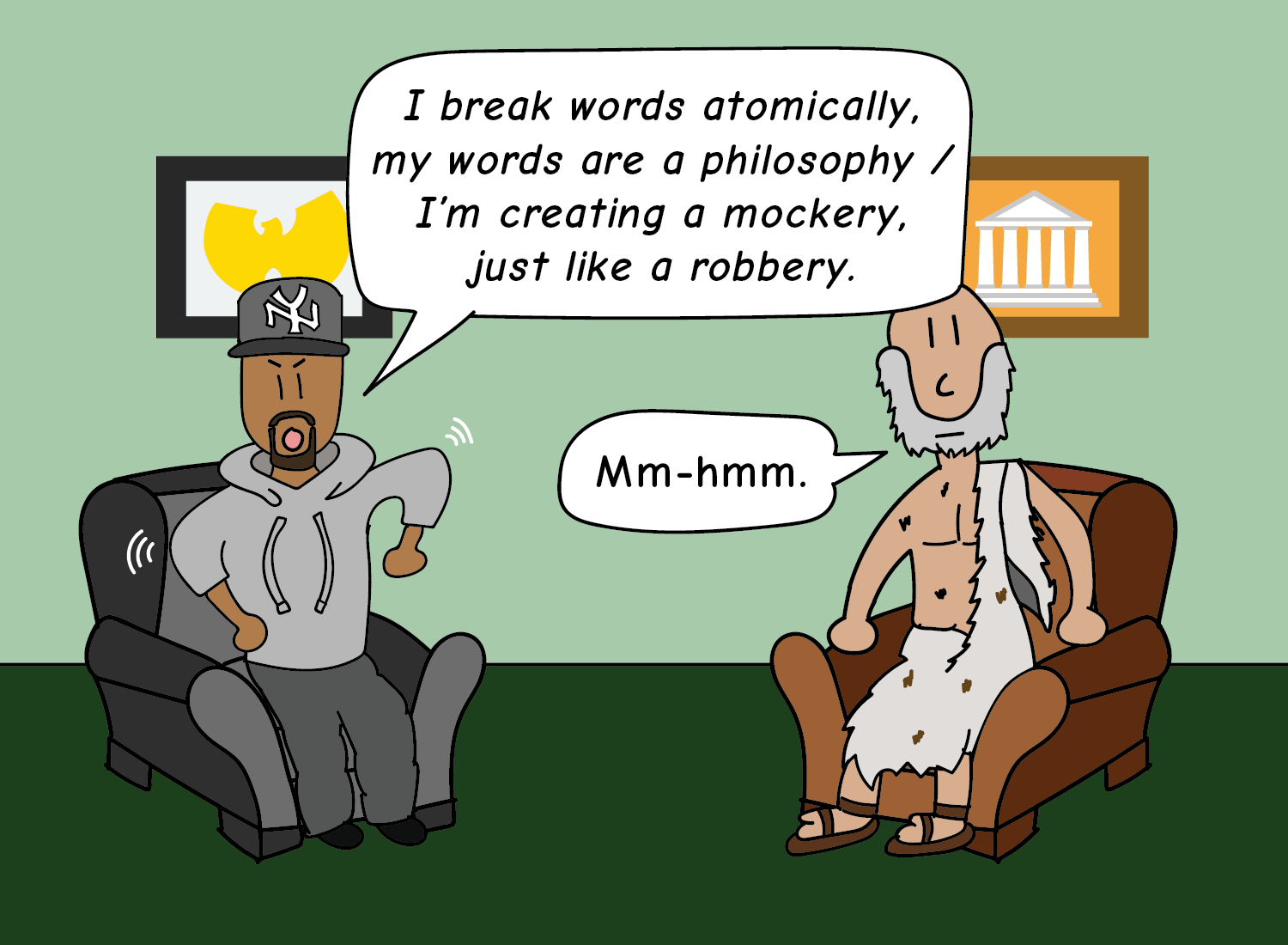

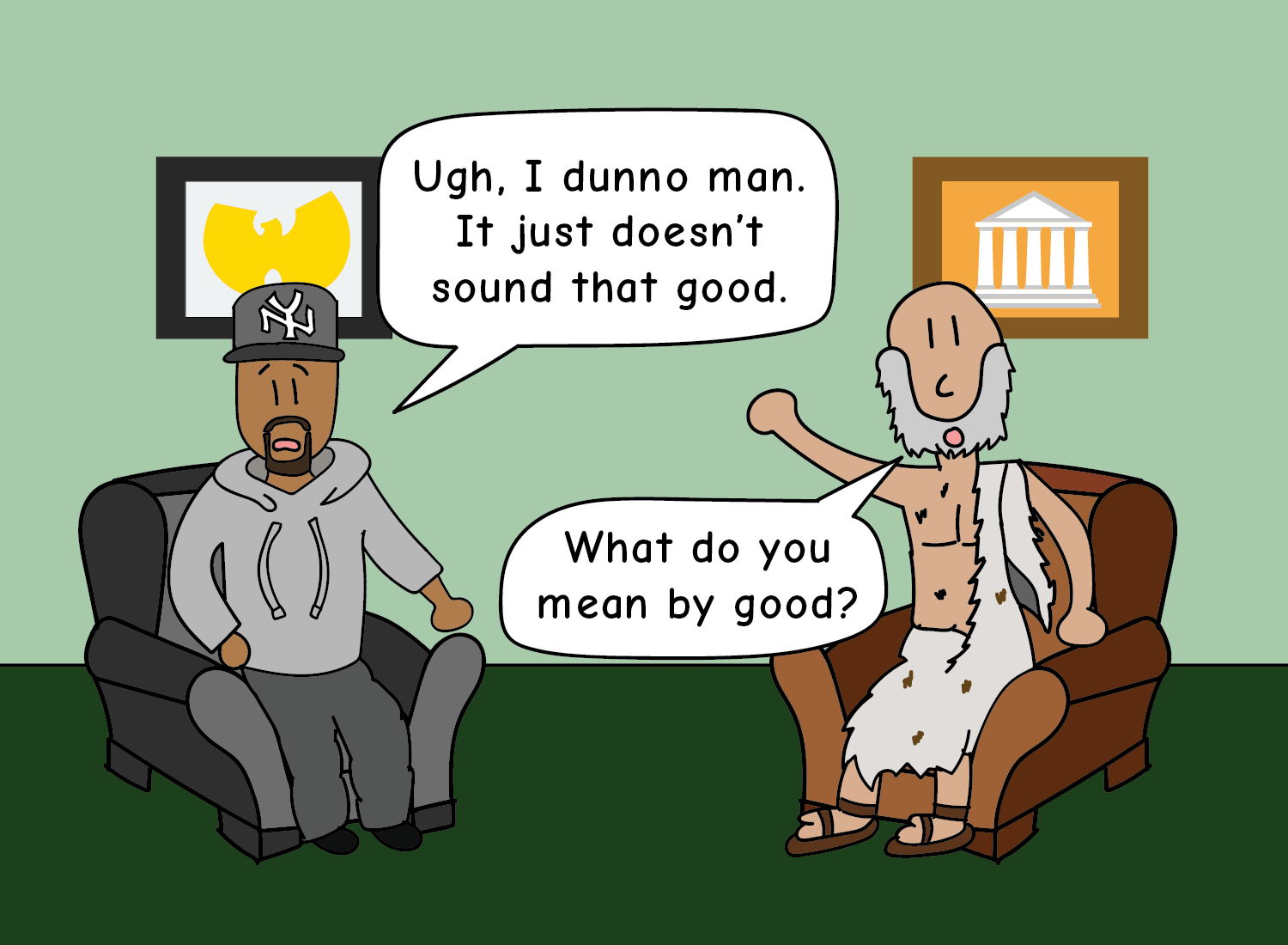

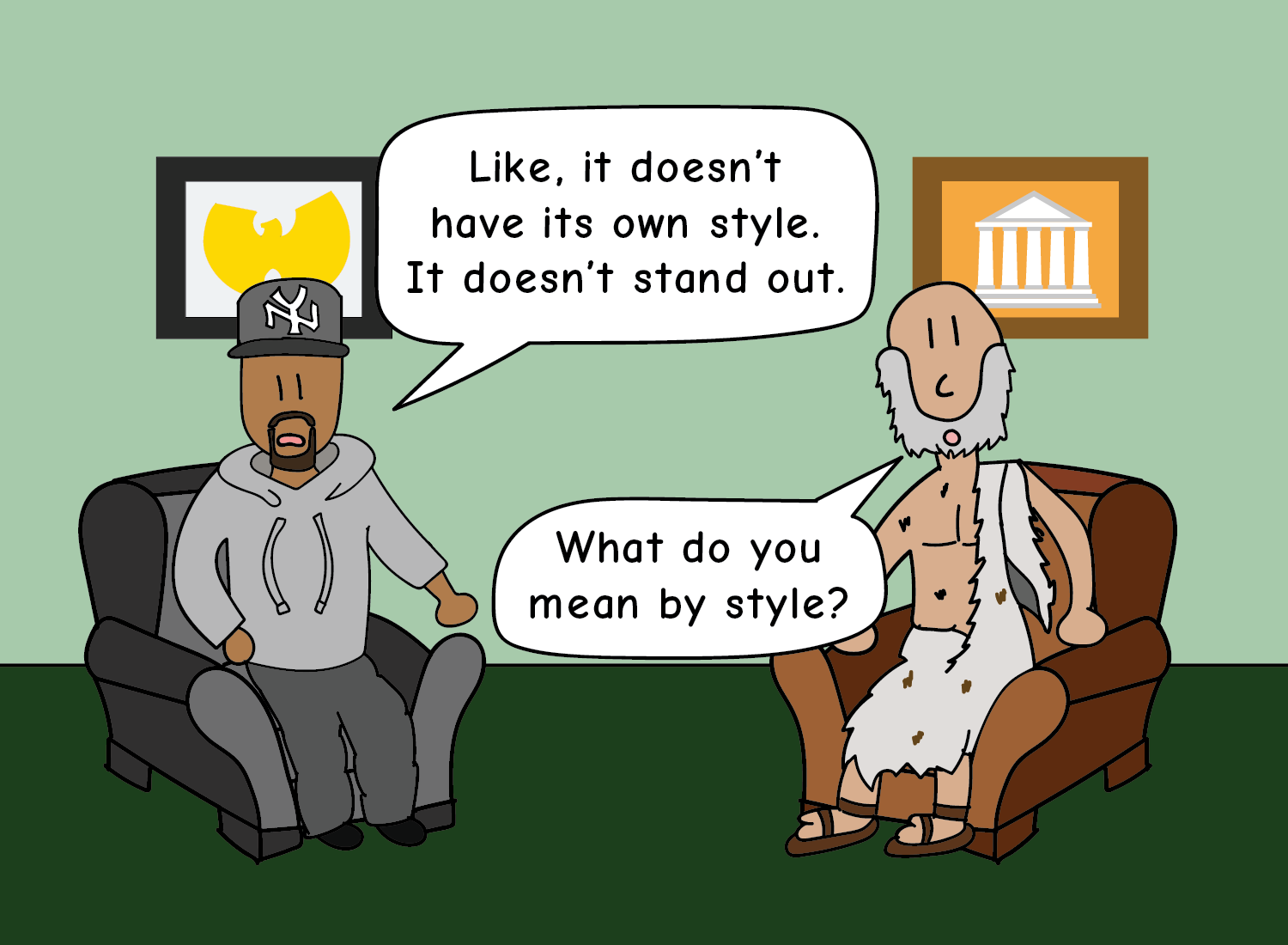

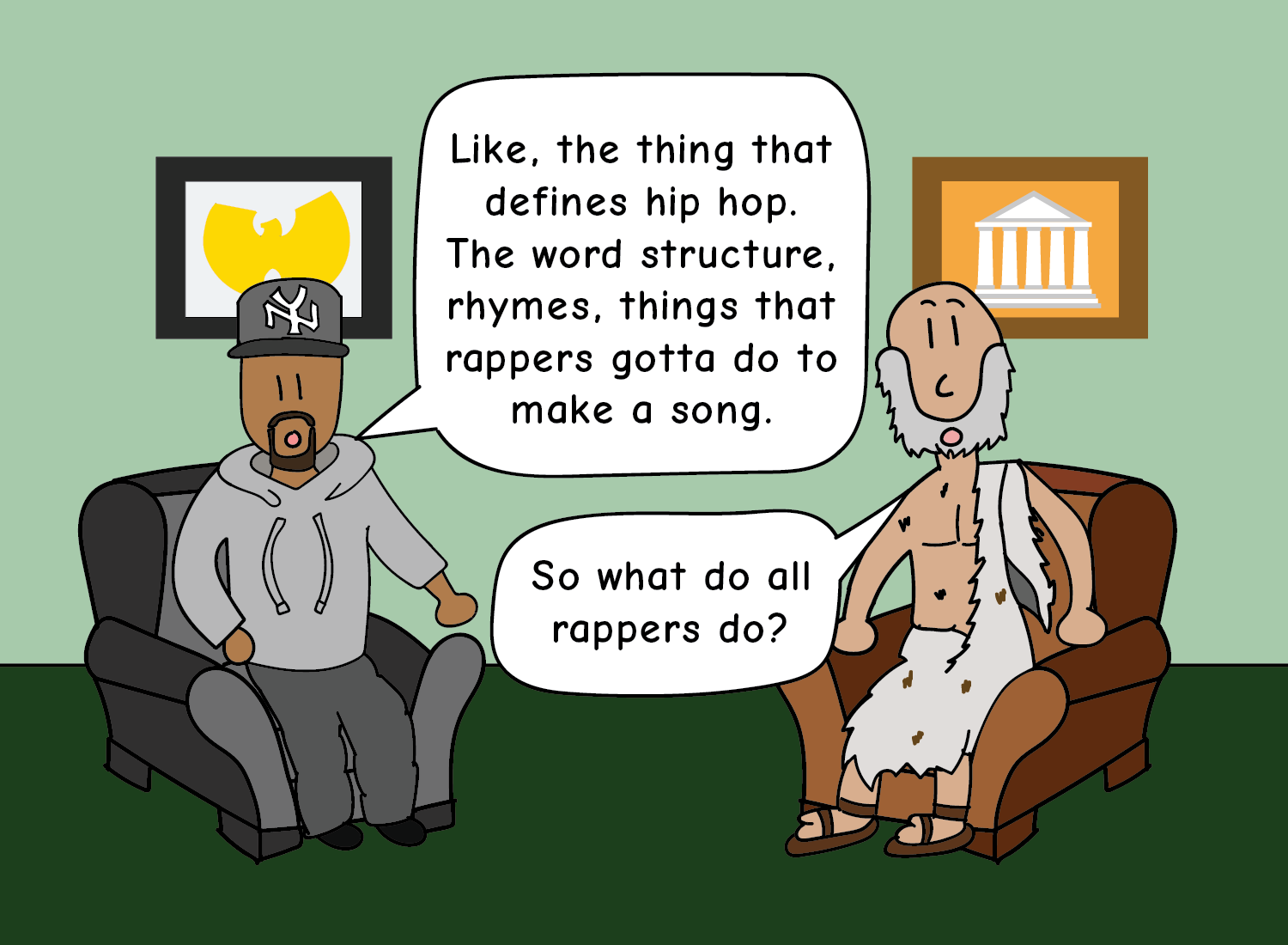

To illustrate the Socratic Method at work, let’s bring back Inspectah Deck, who just met Socrates for the first time.

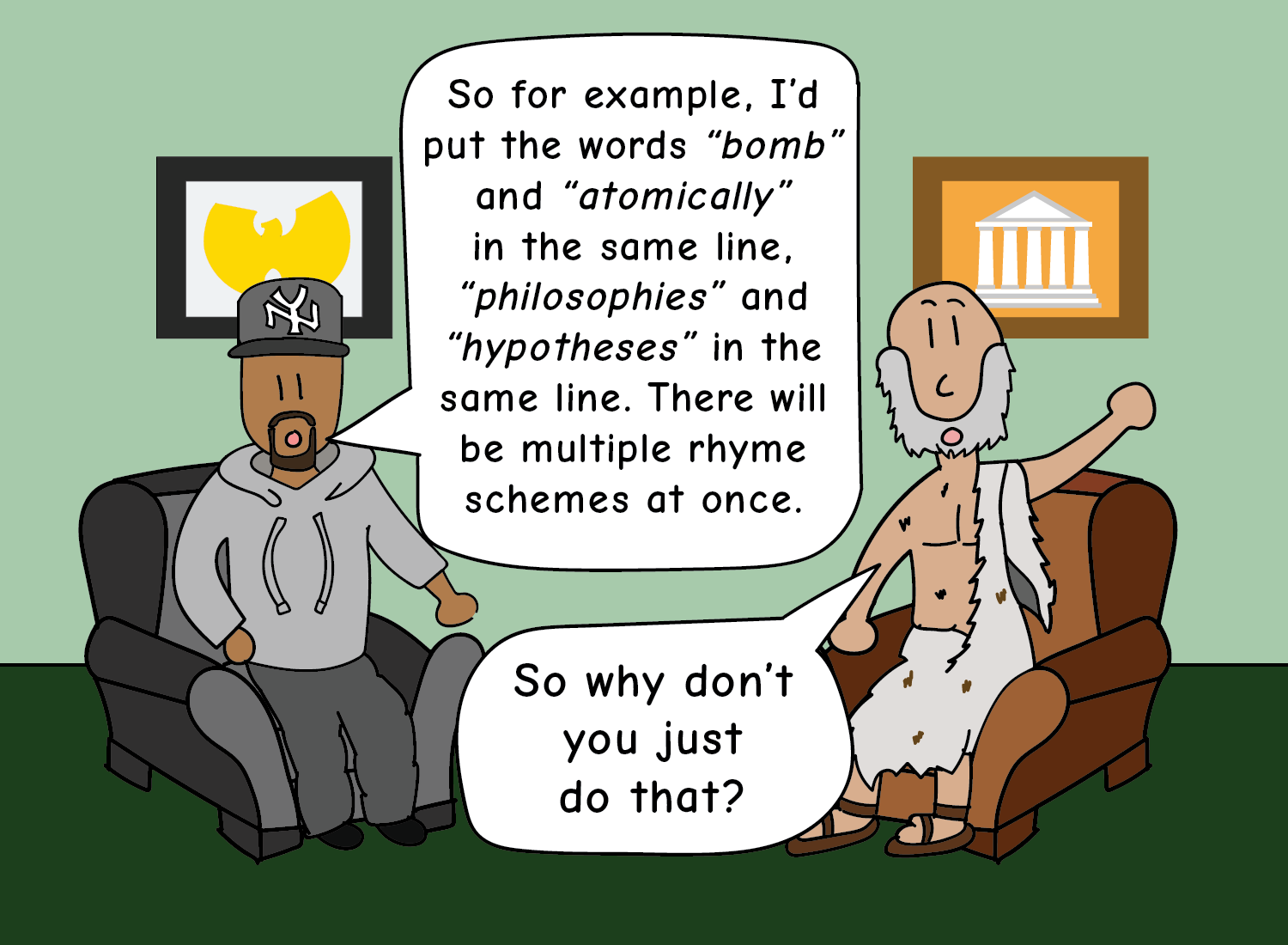

After Inspectah Deck gets over his initial shock at Socrates’ I-don’t-give-a-fuck appearance, he then opens up to him about how he’s having a hard time putting together the opening lines of his verse on “Triumph.” The discussion may have gone something like this:

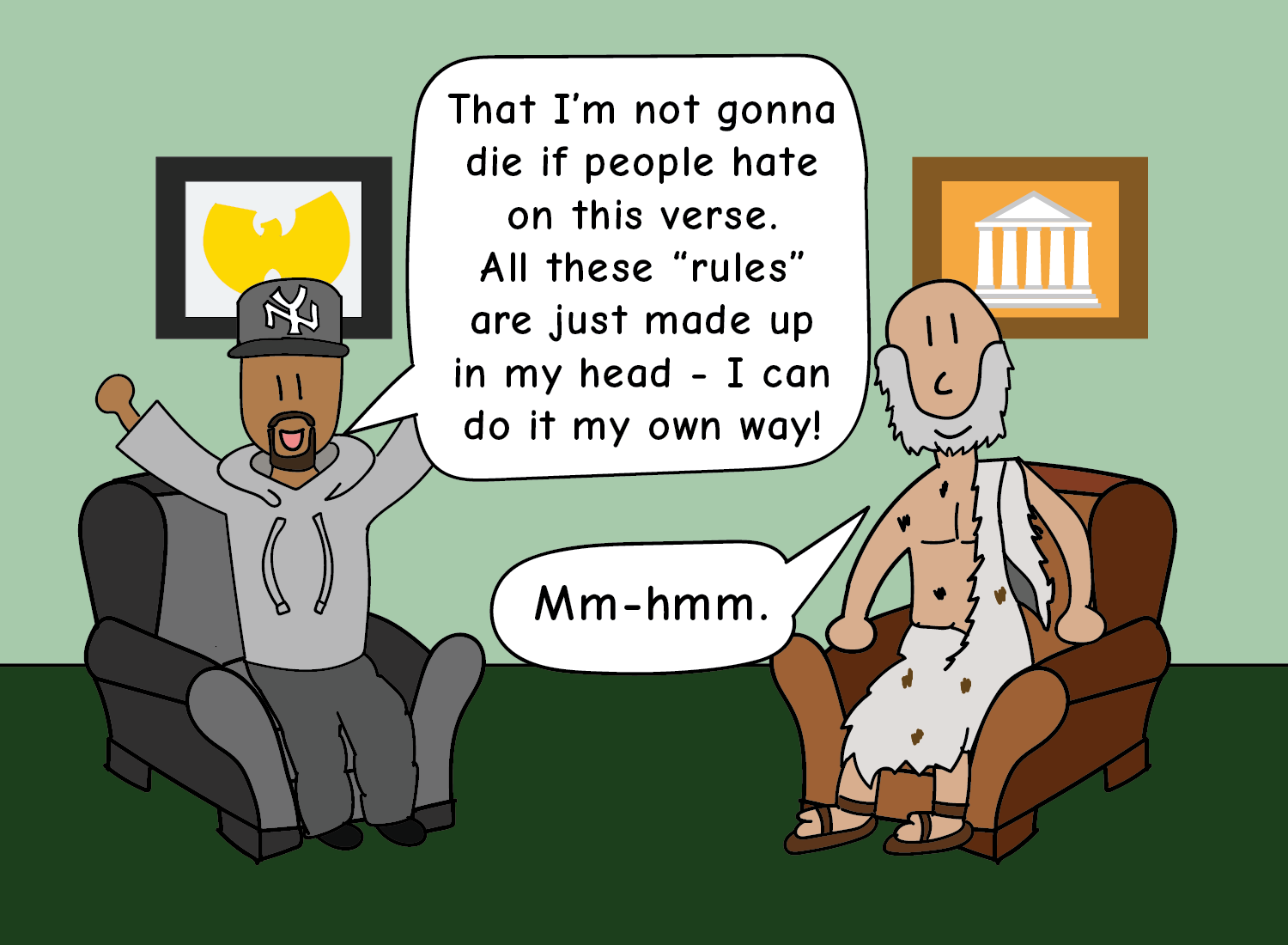

At first glance, this conversation may simply look like a guy asking way too many questions. But underneath the hood, there’s so much happening here.

Throughout the dialogue, Socrates was asking Inspectah Deck what he meant by certain words like “good” or “style.” He wanted him to define exactly what those words meant, as they created the entire basis of Inspectah Deck’s critique of his own verse. Without understanding these foundational definitions, it was impossible to get to the root of why Inspectah Deck thought he couldn’t switch up his wordplay. There were assumptions he was making about what “good” lyrics were according to the “rules” of hip hop, when in reality, he was free to do whatever he wanted.

Socrates used the tool of questioning to strip away all preconceived notions and dogmas surrounding one’s cherished beliefs. Instead of giving directives, Socrates believed that asking difficult questions forced people to articulate their thoughts, and during the process, they would notice the contradictions in their reasoning.

Questions were the tools that slowly chipped away all assumptions and falsehoods, and got you somewhat closer to the truth in the process.

The Sophists believed that we all have our own truths, and life was about persuading others to believe them. We already knew everything there was to know, so there was no further introspection necessary. The Sophists hated uncertainty, and so did most thinkers before Socrates came along.

Socrates was one of the first philosophers to challenge this belief, and to instead assert that we all don’t know shit. There is an ultimate, absolute truth out there, but there’s just no way to know what it is. The starting point for all inquiry comes from the acceptance of the fact that we don’t know anything, and it’s up to us to learn more about the world by eliminating our biases and falsehoods.

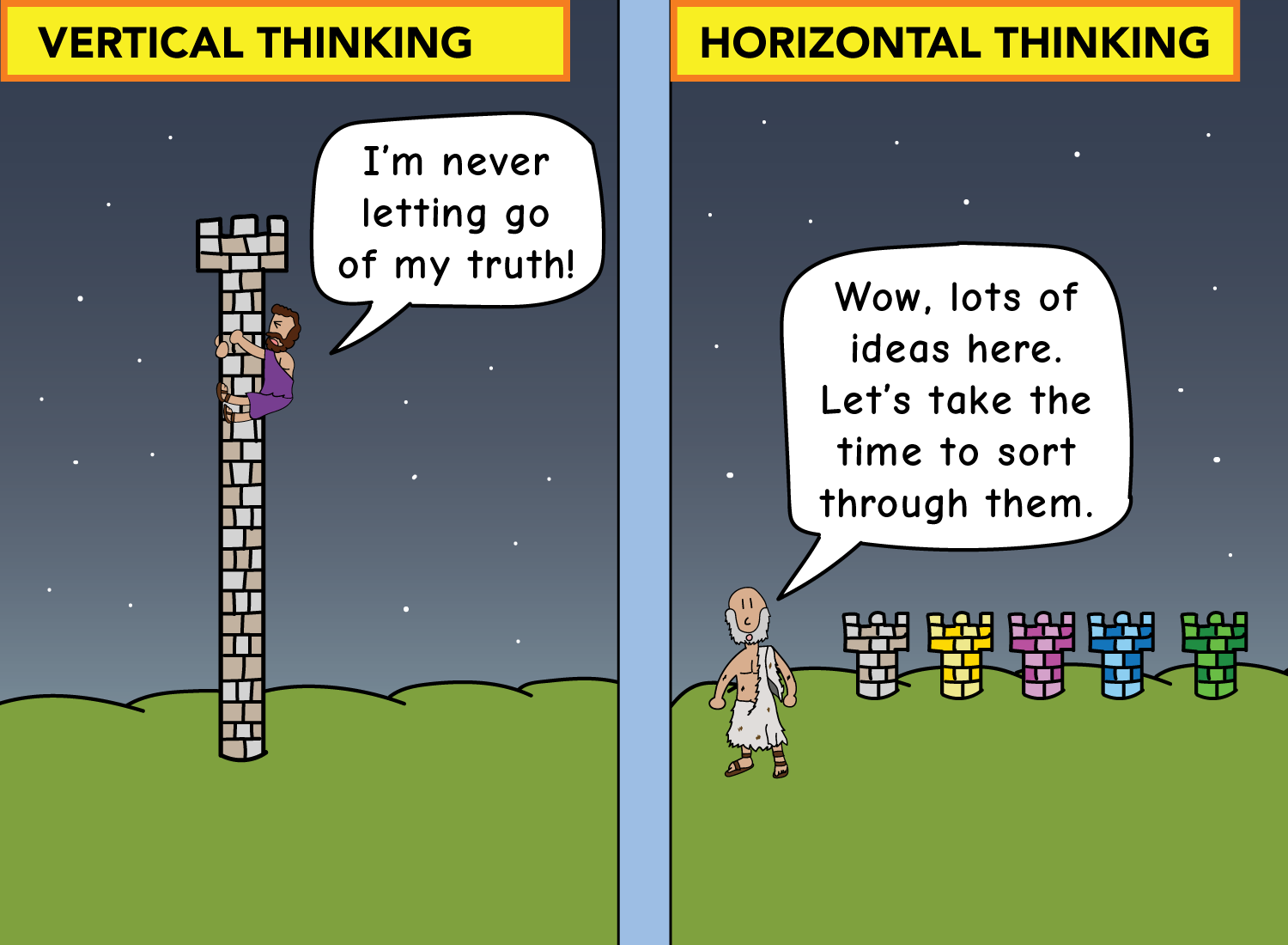

The Sophists thought vertically, starting with certainty and building their case on top of it. Socrates, on the other hand, thought horizontally, starting with uncertainty and gradually whittling down possible ideas to arrive at the truth. There is a vast landscape of ideas out there, and it’s our responsibility to unearth the falsehoods and discard them.

A famous example of Socrates’ horizontal thinking is what happened when a reputable (and drugged-up-on-ethylene) oracle called him the wisest man in all of Athens. Instead of accepting that statement and building his case on top of it, he thought it was suspect and immediately hit the streets to find someone wiser than him. He wanted to converse with all possible data points out there to test whether or not the oracle’s statement was true.

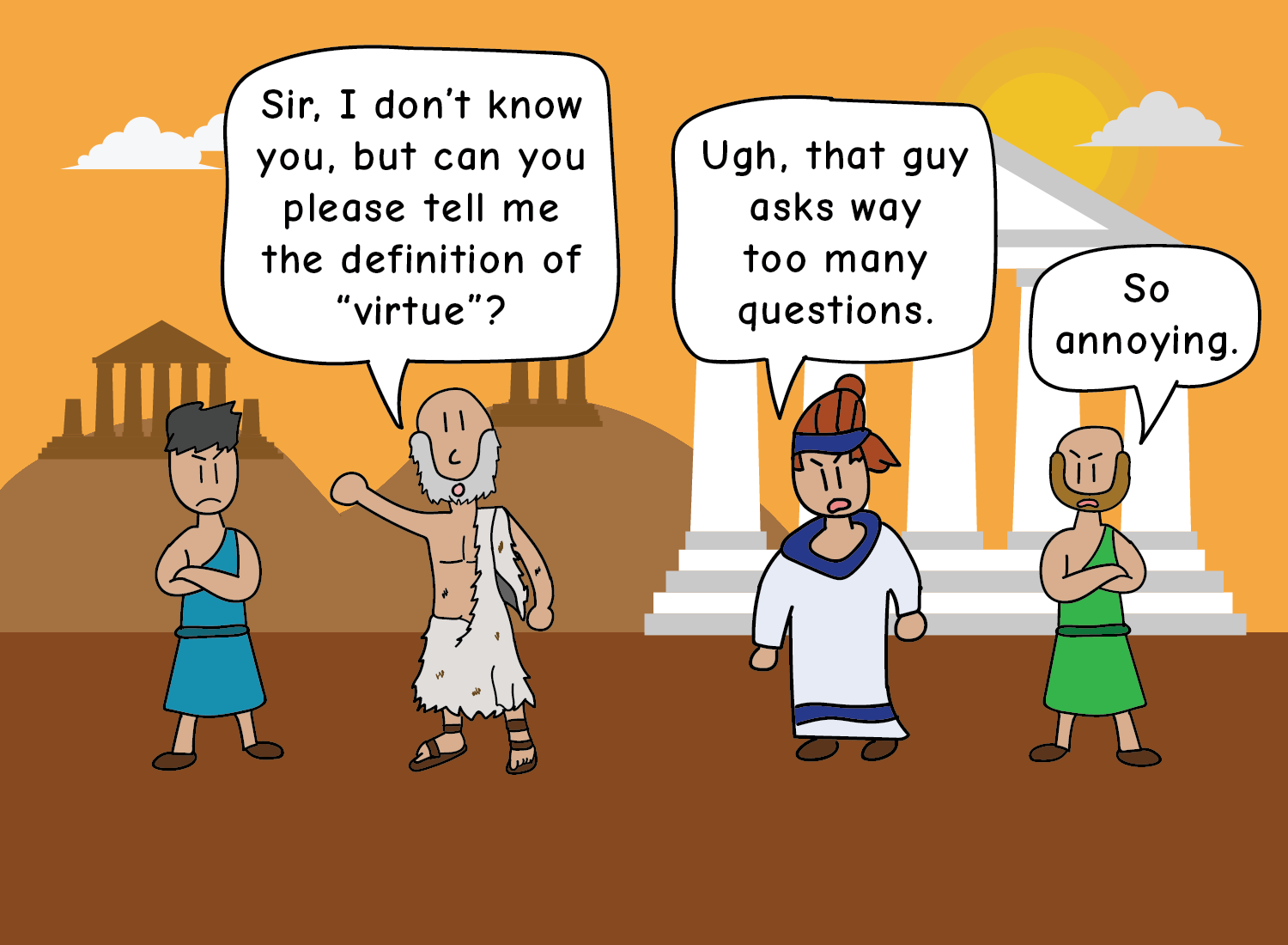

He would randomly stop people, asking them loaded things like what they thought “virtue” or “justice” was. If they indulged and provided an answer, he would then ask them why they thought that, what they meant by the words they were using, and probably why they were no longer having fun after a few minutes.

This relentless approach left a lot of people frustrated and angered by this man that wouldn’t stop asking questions. We already feel the tinges of annoyance when a cute child asks “why” five times in a row, but now take that child, make him a 50-year-old man, and have him smell like straight butthole. It’s not surprising to hear that he was reviled by some.

The people that disliked Socrates thought vertically, so when he tried to show them that their cherished foundations were faulty, they refused to let go of their beliefs. Most people doubled down on their idea of truth, and felt like Socrates was mocking them and trying to make them feel stupid by asking them to elaborate on it. The reality, however, was that Socrates wasn’t trying to make anyone feel stupid; he just wanted them to be aware of the blind spots in their thinking.

What he noticed was that people often had no idea what the hell they were talking about, but were too pompous to admit it. After observing this over and over again, Socrates came to the cheeky conclusion that the oracle was right along. He was, in fact, the wisest man in Athens, but not because he knew more than everyone else. He knew just as little as the next guy, but the difference was that he was the only one that would admit it. Or as he famously stated:

This acceptance of uncertainty as a starting point may be common sense now, but it was a radical viewpoint in the fifth century BC. Socrates, however, didn’t care what people thought. After realizing how little people understood about the nature of reality, he made it his mission to hit the streets and use the Socratic method vigorously. He would stop everyone – from day laborers to high court officials – and question the foundations of their knowledge so they could better understand the truth (which is that we all don’t know shit).

But like all radicals, Socrates had his fair share of enemies. Not only were there people that hated his incessant questioning, there were also people that wanted him dead for his political views. In short, Socrates was critical of democracy during a time where Athens was really nervous about any anti-democratic sentiment. In 404 BC, neighboring Sparta (of “300” fame) took over Athens and imposed an ultra-violent, ruthless oligarchic rule that lasted for a year (1,500 residents were purged and killed during their reign). Athenians hastily fought back, overthrew them, and re-established democracy, but were still very much on edge while reassembling the pieces.

Then there was Socrates, an already infamous man, strengthening his hate-magnetism by publicly speaking out against democratic values. This proved to be the final straw; the Athenians saw enough. In 399 BC, a five-hundred-person jury convicted him of two ridiculous criminal charges (“corrupting the youth” and “not believing in the gods the state believes in”), and he was sentenced to death by drinking a poisonous substance called hemlock.

The consensus among scholars is that Socrates could have easily avoided execution by either (1) using his superior intellect to argue his way out of it, (2) apologizing to the jury for his actions, or (3) allowing his pupils to bribe the prison guards and have him escape. Socrates, however, chose none of these options, and proceeded to make his case, even taunting the jury by telling them they should be thanking him for his service instead. He had lived his whole life for this moment, for he believed that “[a]ll of philosophy is training for death.”

On his final day on this earth, he was in the company of his friends, many of whom were tearing up and crying at the thought of losing their beloved companion. In true Socratic fashion, he noticed this and remarked:

“You are strange fellows, what is wrong with you? . . . I have heard that one should die in silence. So please be quiet and keep control of yourselves.”

What a badass.

He then downed the poison like a 40-ounce can of Red Bull, walked around, and laid down after his legs became Socratic jelly. After hanging out for a few moments, the poison reached his heart, and he took his last breath.

That was the life of Socrates. He was seventy years old when he died, but went on to influence the fields of philosophy and scientific inquiry for millennia to come. He’s a household name that we commonly equate with intelligence, but I think the better word here would be “curiosity.” He was fascinated by a world filled with questions, and not answers. He understood that our view of the world was limited by the scope of our minds, and the tool to expand that field of vision was introspection.

When I reflect on the story of Socrates, I wonder what I would have done if I were one of the 500 jury members that were trying him. Would I have called for his death? Would I have jeered at his unkemptness, viewed him as a second-class citizen, and thought of him as a “crazy guy” that went around asking way too many fucking questions?

Or would I have seen something brilliant, something that showed me there’s more to truth than what the Sophists thought? Would I have agreed that I really don’t know anything, accept that fact, and try to move forward?

History gives us the benefit of hindsight, and that allows us to nicely categorize things that may have been ambiguous at the time. It’s easy to say that Socrates = Greatness now, but we do require a kind of wisdom and clarity for us to believe that when they’re still alive. The same could be true for all other figures that we laud as heroes today. Martin Luther King, Jr., Gandhi, Susan B. Anthony, the Buddha, Galileo, the list goes on.

Would we have been on the right side of history for all these people as well?

Would we have been open to beliefs that went against the conventional wisdom of the time?

Interestingly enough, I feel that Socrates’s worldview helps to answer these questions with these three takeaways:

(1) Place uncertainty as the starting point to truth.

All dogmatic, tribal, and judgmental thought starts with misplaced certainty. If you believe you know everything there is to know, then all contradictory points will sound like gibberish, no matter how much the evidence favors it. If you are certain that global warming is bullshit, then it doesn’t matter how much evidence you’re shown that contradicts that view; you’ll refuse to entertain it.

This doesn’t just apply to concepts, it also applies to individuals. If you are certain that this 10-year-old African-American kid from Hawaii will never make anything of his life, then you’ll be angry as hell when you find out that one day he’s become the President of the United States.

You can’t start from your elusive version of truth, and try to manipulate the world to validate your claims. Sorry, but if you haven’t noticed by now, the natural world doesn’t give a fuck about us. We are a part of a fundamentally mysterious universe that we still know next to nothing about, and that’s the overarching law of our existence.

Socrates believed that intellectual humility was the starting point for self-examination. So much of our lives have been unknowingly built by the hands of others, and we need to strip away these expectations and assumptions, leaving behind only the facts to build up the proper conclusions. This is known as inductive reasoning, and is the backbone of a little something called the scientific method. If it’s worked well for the advancement of science, it can work well for us.

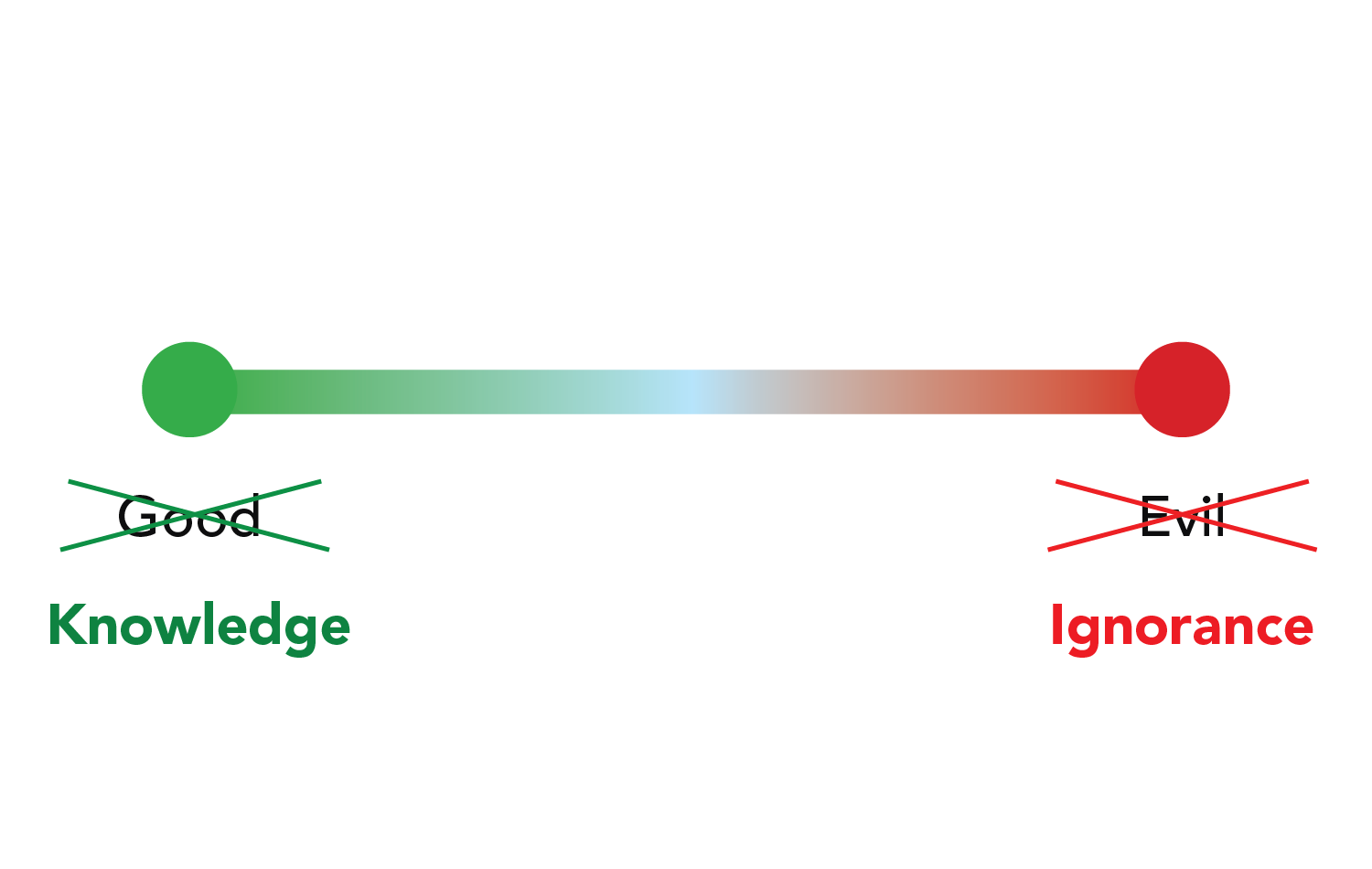

(2) Life isn’t about being good or evil; it’s about being less ignorant and more knowledgeable.

Socrates believed that there was a universal, objective truth governing the world, but comprehending it was beyond our scope. Not only was this true for the material world, it was also true for our moral principles.

The Sophists went back and forth arguing about was “wise” and what was “good,” but Socrates would argue that it’s impossible to define what “good” is in the first place. Every generation tries to enforce morality through the usage of the law, but history has shown us repeatedly that our intuitions fail here.

Slavery was a legal institution throughout most of human history, men had the rights to put their wives to death if they were unfaithful, and Jim Crow laws were alive in America just one generation ago. If our moral judgments are known to be this shitty and change all the time, how can we assert that one is more right than the other?

Socrates would say that none of these are, given that we’re in no position to judge what’s “good” in the first place. We can’t even define what this word means, and we never will. Instead of viewing the world as a battle between good vs. evil, the only way to view it is through the lens of knowledge vs. ignorance:

Socrates famously said that “[t]here is only one good, knowledge, and one evil, ignorance.” He believed that if we took the time to learn more about ourselves, the way we think, and the faulty preconceptions we hold, it won’t be possible for us to go around harming ourselves and others. Our greatest enemy is not some external demon, it’s our inner ignorance. Knowledge is the only path to virtue, and it’s up to us to improve upon it as much as possible.

(3) Anyone can be a philosopher. In fact, everyone should be.

If knowledge is the ultimate goal, then self-reflection is the tool to get us there. Thinking is not a form of entertainment; it’s the only way for us to update our understanding of how to live a meaningful life. Otherwise we’d be a slave to our impulses, blindly following the whims of a mind that desires only the pleasurable.

Before Socrates, practicing philosophy was like getting a VIP table at a gentlemen’s club. It was a luxury that only a few wealthy people were eligible to partake in, and women weren’t even allowed to practice it. But in came Socrates, who promptly said fuck all that noise. He believed that everyone, regardless of status or sex, should reflect on their lives to understand the path they’re on. This belief is embodied by his most famous quote, which he proclaimed during his trial:

Socrates believed that without introspection, you will never have the knowledge to lead a life of virtue. However, that was just one part of the equation. Of equal importance is the ability to have open, good-faith discussion with others.

Socrates never wrote anything down, as he believed that discourse and discussion was the true path to wisdom. It wasn’t enough to have everything live in your head; you had to test these ideas against the questions and arguments of others. It’s only through these iterative discussions that we can all improve upon the quality of what we (think we) know.

I like to think of Socrates as a brilliant node in a vibrant network of ideas. He was one of the first philosophers to encourage everyone to reflect on their lives, and to share those ideas and thoughts with everyone else. He was a founder of a deep social network that was less about your pictures, and more about your worldviews.

About five hundred years after Socrates’ death, the influential Roman orator, Cicero, said this of him:

“Socrates was the first who called philosophy down from heaven, and placed it in cities, and introduced it even in homes, and drove it to inquire about life and customs and things good and evil.”

We take it for granted that we can listen to philosophy podcasts, access any great thinker’s mind for free in the local library, and deeply examine our lives with others. Philosophy used to sit in an ivory tower, distanced from the general public, continuing its vertical construction through arrogant certainty. Socrates saw so many problems with this, and leveled the playing field by arguing that uncertainty and questions were the only way to glimpse the truth.

Without questions, there is no dialogue, and without dialogue, we have no philosophy. It’s our duty to become philosophers, ask relentlessly, and keep the vast network of ideas thriving.

The story of Socrates’ life is one of great legacy and deep sadness. His legacy lives on in the form of the Socratic method, but this very method is what got him killed. He was ruthlessly ridiculed and handed a literal death sentence, just for asking questions.

The most dangerous feature of a hardened ego is its magnetism toward other hardened egos. Nothing forms a mob faster than people that refuse to shed their cherished beliefs, and nothing threatens them more than an intelligent person that challenges their assumptions.

Socrates faced this mob directly, and died so his ideas would live on. On his last day, he seemed to have understood this when he told his friends,

“Be of good cheer . . . and say that you are burying my body only.”

You’re right, Socrates – your body is long gone, but you still live on today.

Thanks to your wisdom, we can all be philosophers in the same way you were. And thanks to your name, we have a great Wu-Tang verse to enjoy for many years to come.

_______________

_______________

Here are some additional More To That posts to keep you company:

To delve into the philosophical rabbit hole even further, check out this two-part post on the foundations of knowledge.

Or for something short and sweet, here’s a quick reminder to apply what you know to who you know best.

_______________

References

If you want to learn more about Socrates, here is one book, one podcast, and one article that I found insightful.

The Book: Will Durant – The Story of Philosophy (this has a short yet informative section on him)

The Podcast: Philosophize This! – Socrates and the Sophists

The Article: Cher Yi – An Examination of Socrates