Shocks, Setbacks, and the Slowdown of Time

In the opening chapter of his book, The Order of Time, physicist Carlo Rovelli writes:

“Let’s begin with a simple fact: time passes faster in the mountains than it does at sea level.”

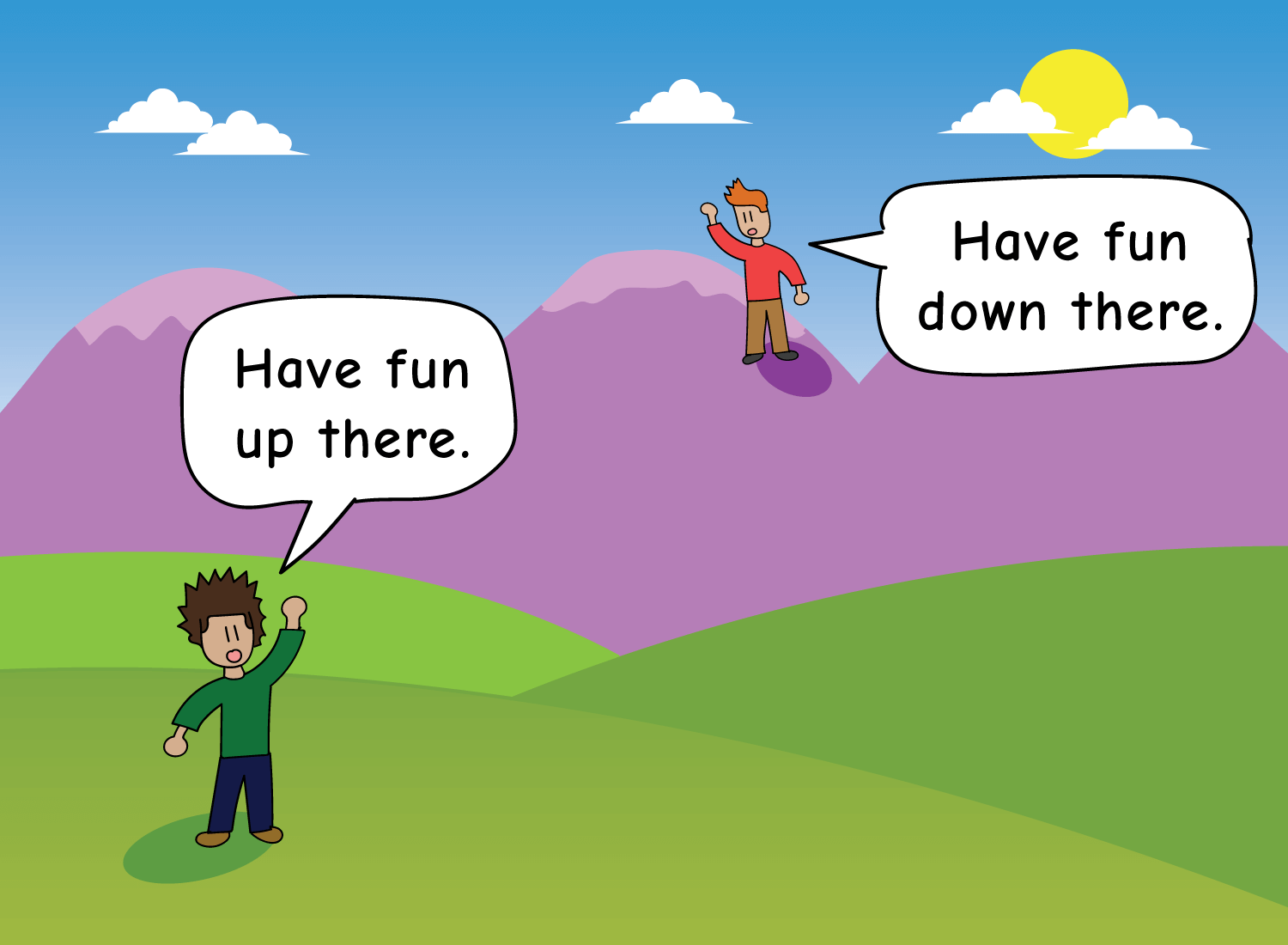

He describes a situation where two friends separate, with one going to live in the mountains and one moving to the plains:

When they meet up years later, the one who lived high up in the mountains will have aged more than the one who lived closer to sea level.

This may sound surprising, but it has been repeatedly proven with the usage of specialized timepieces. This holds true even within the narrowest of altitude differences: a clock placed on the floor will run slower than one that is on a table.

The best part, however, was that someone understood this phenomenon well before we had clocks precise enough to measure it. His name, of course, was Albert Einstein.

Rovelli describes what Einstein figured out (emphasis mine):

He imagined that the sun and the Earth each modified the space and time that surrounded them, just as a body immersed in water displaces the water around it. This modification of the structure of time influences in turn the movement of bodies, causing them to “fall” toward each other.

What does it mean, this “modification of the structure of time”? It means precisely the slowing down of time above: a mass slows down time around itself. The Earth is a large mass and slows down time in its vicinity. It does so more in the plains and less in the mountains, because the plains are closer to it. This is why the friend who stays at sea level ages more slowly.

Or to illustrate this phenomenon as it relates to our two friends:

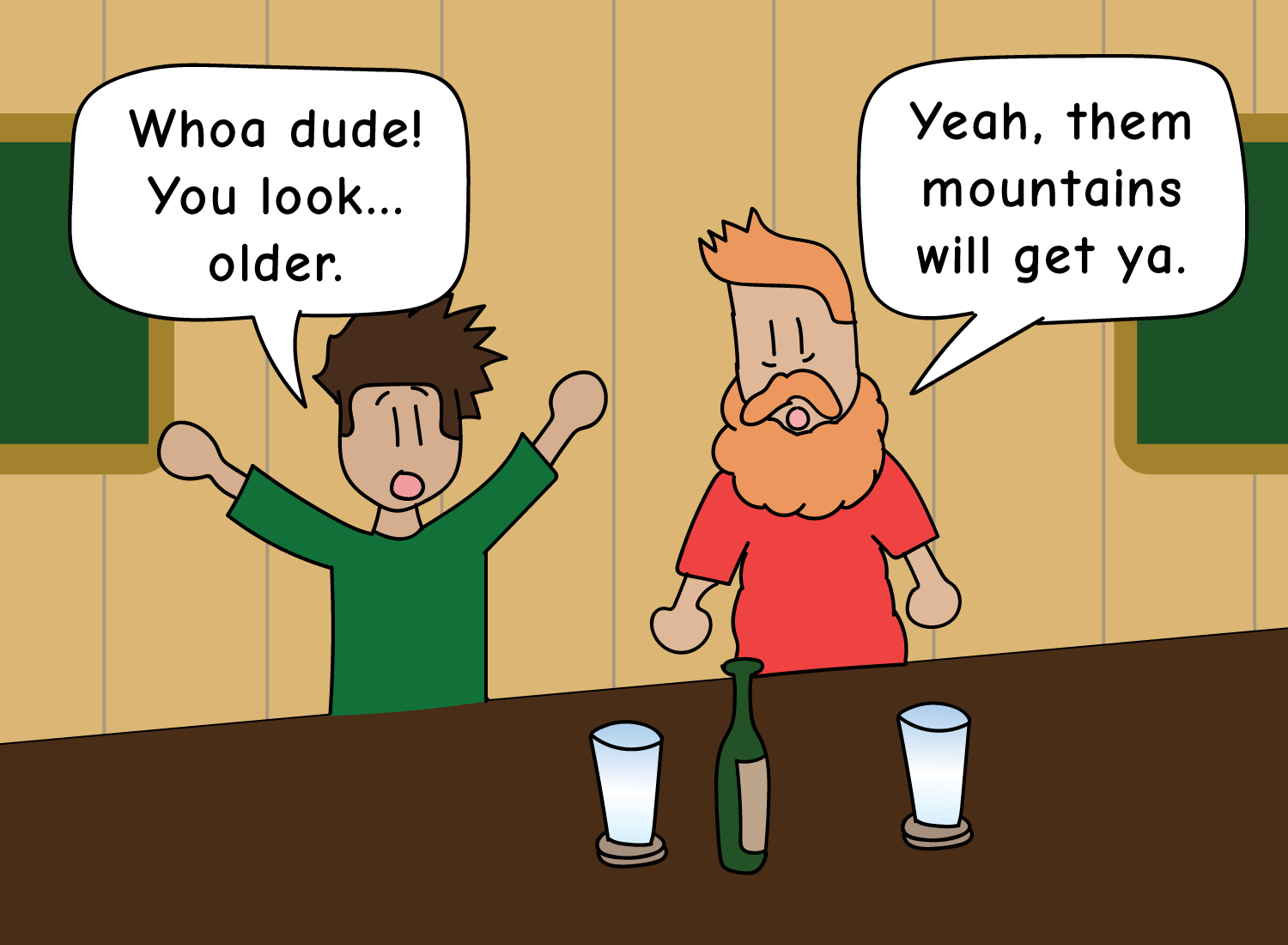

Much of this lies at the heart of Einstein’s famous theory of relativity, but for our purposes, the key takeaway is that the closer you are to Earth, the slower time will be for you. Live in the plains for ten years, and your face will have less wrinkles than your buddy’s that dwelled in the mountaintops for a decade.

Much of this lies at the heart of Einstein’s famous theory of relativity, but for our purposes, the key takeaway is that the closer you are to Earth, the slower time will be for you. Live in the plains for ten years, and your face will have less wrinkles than your buddy’s that dwelled in the mountaintops for a decade.

This observation is governed by the laws of physics, and explains the relative nature of time. However, this doesn’t quite explain the differences we feel in the relative perception of time.

Time appears to slow down or speed up depending on the situations we find ourselves in. Some moments feel like they go by within the blink of an eye, but others feel like they’re moving at a snail’s pace. What is the mechanism that drives this perceptual change of time?

The lens of physics cannot be used to answer this question. Instead, we must look inward, and use philosophy instead.

The Gravitational Pull of Shocks

We are creatures of habit and routine. If one were to map our daily activities across a landscape of events, they would find remarkable overlap between this day and the next, this week and the next, this month and the next, and so on.

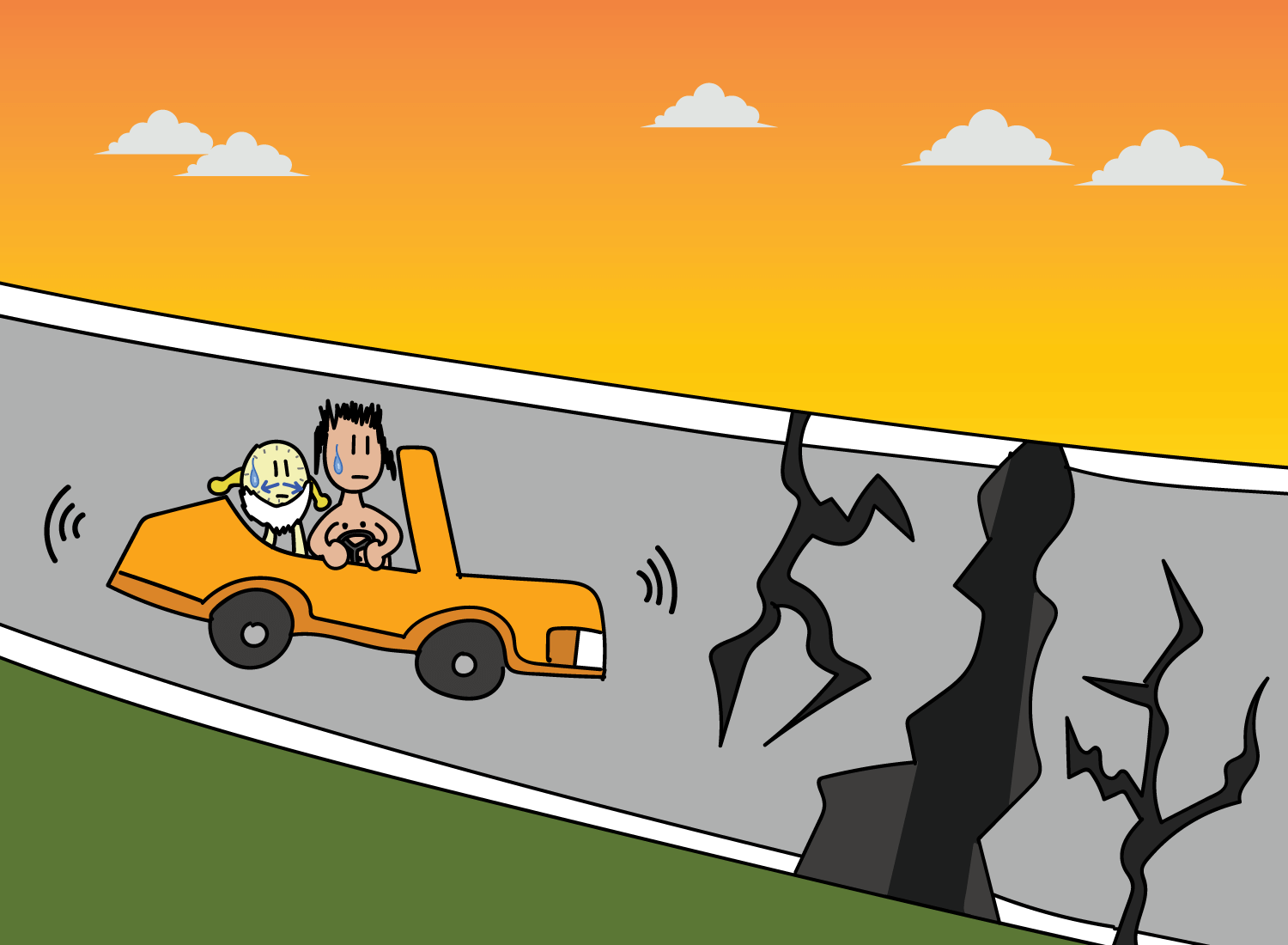

The utility of a routine lies in its predictability – it frees your mind from having to make unnecessary decisions like what time to wake up or where you need to be for work. They are reliable guideposts for a well-mapped day, and if you adhere to them successfully, it will feel like you’re driving down a familiar highway at 80 miles an hour, coasting toward the end of each day as Father Time rides in the passenger seat with you.

As nice as this may sound, this highway is bound to be disturbed.

Life shocks come in various forms, and in varying magnitudes. Sometimes they are deeply personal, and it seems like only you have to go through a difficult situation that you failed to predict. Perhaps you got fired from your job or your partner hands you divorce papers; these are shocks that appear to be localized solely to your unique circumstances.

But other times they feel collective, and there’s an understanding at a much larger level that a life shock is being shared amongst many. 9/11 was an example of this for the United States, and currently, the entire world is embroiled in a pandemic that will have lasting consequences on every facet of life.

In these moments, time appears to slow down dramatically, with each minute extending to an hour, and each hour extending to a day. For many of us, the last week has felt like a whole month as routines have been nullified, financial worries have been introduced, and any semblance of predictability has been effectively discarded.

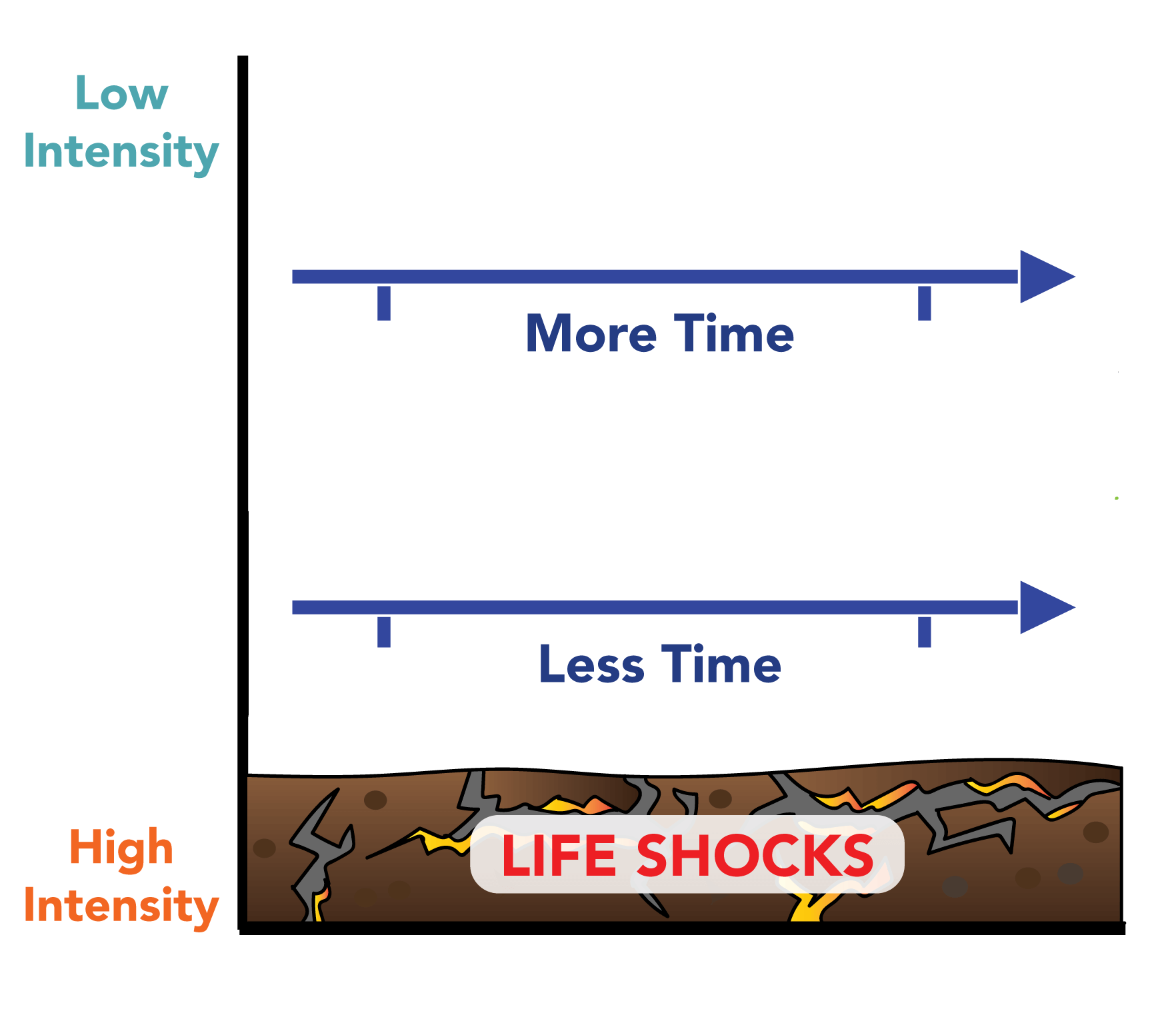

Physics reveals that time slows down as we get closer to a body of mass, but philosophy reveals that time slows down as we get closer to the intensity of shock.

It is widely accepted that life struggles are what make us stronger, but we often fail to acknowledge how this slowing down of time is what facilitates this mental resilience.

It is widely accepted that life struggles are what make us stronger, but we often fail to acknowledge how this slowing down of time is what facilitates this mental resilience.

When time slows, the capacity for awareness grows in its wake. All of a sudden, the things that were previously covered by the haze of routine become more evident, and they shift a few more steps to the foreground as a result.

For example, take what’s going on with the coronavirus pandemic and how it’s placing an elevated emphasis on connecting with friends and family.

A few months ago we were living our day-to-day, routine-driven lives: waking up in the morning, going to work, coming back home, eating dinner, winding down, and sleeping so we could do it all over again the next day. Checking in with friends and family was more of an afterthought, something that was primarily reserved for special occasions or the weekends (aka that window of time where spontaneity is given a brief moment to swing by).

But as the days have grown longer, our awareness of our closest relationships are given the proper space to bloom, and more importantly, we are following up on that awareness by acting on it quickly. In the last week alone, I was on a Group FaceTime chat with my high school friends for the first time, a Zoom call with my wife’s family for the first time, and was exchanging a flurry of text messages with people I haven’t checked in with for months as well.

The most interesting part is that many of these loved ones don’t live near me in the first place, so FaceTime chats and Zoom calls would have been suitable at any moment over the last few years. However, we all felt the collective urge to do this now as opposed to then, as the shock of the pandemic’s impact on everyday life was evident in our minds.

This is the power of a slowdown in time. It gives us the requisite space to take a step back and notice that everything could vanish in an instant, while elevating the importance of what truly matters.

Life shocks create uncertainty, but they also offer the capacity for reflection to navigate the fog ahead.

The True Measurement of Progress

It would be some relief to our frailty and our concerns if everything came to an end as slowly as it comes into existence. The reality is that it takes time for things to grow but little or no time for them to be lost.

-Seneca

It takes years for a country to come out of a recession, but days for it to enter one. It takes years for a body to recover from alcoholism, but just one drink for it to relapse.

Progress builds slowly, shocks erase quickly.

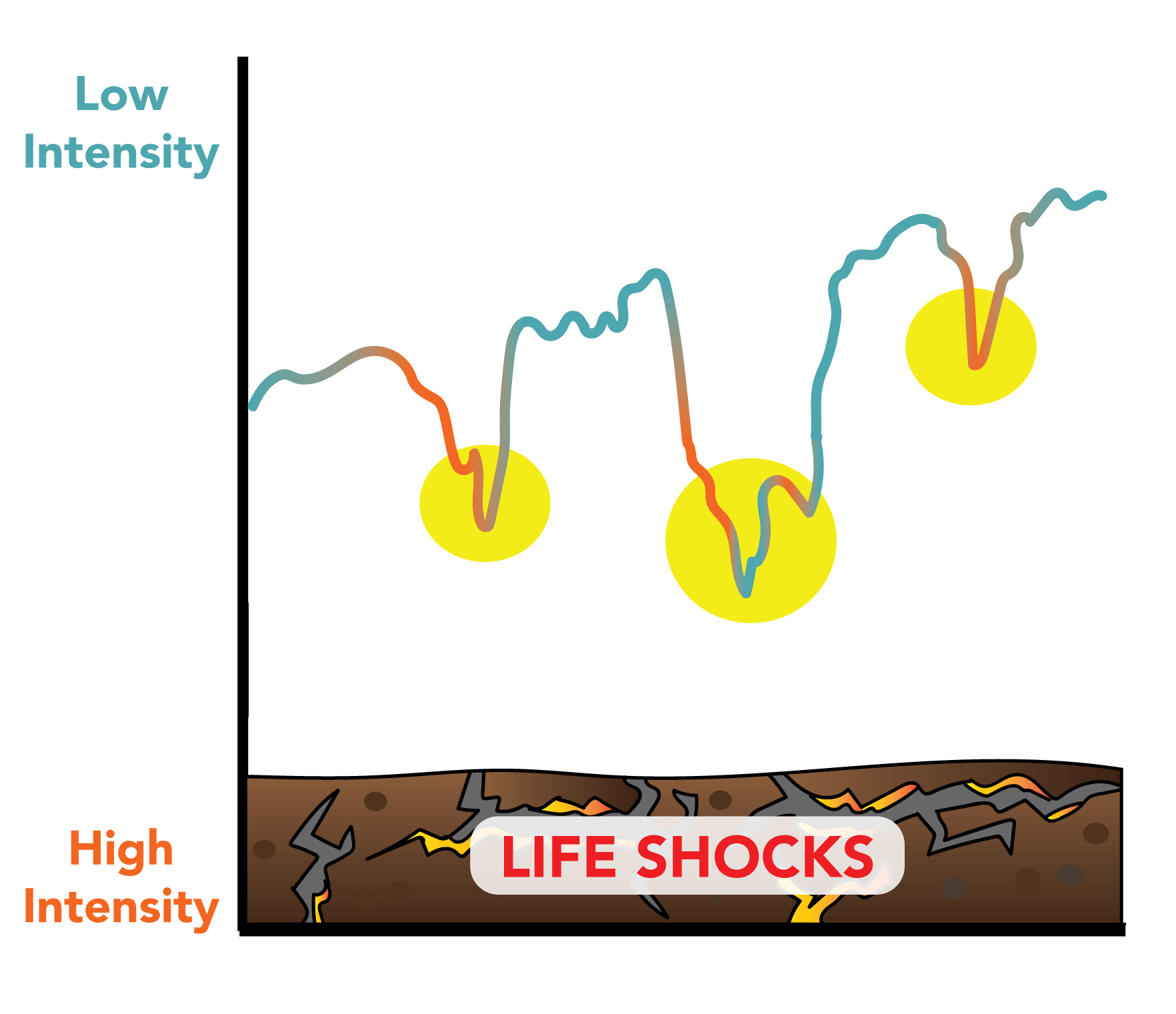

It is this asymmetrical relationship that make life shocks such an important part of our growth. We may spend years cultivating our careers, building our wealth, and establishing our reputations, but these things happen quite naturally with hard work and the passage of time. Shocks, however, are relentlessly unpredictable, and it is how we react to these sharp declines that determines the direction of any future progress to come.

Remember that when you enter one of those yellow circles above, you enter a space where time expands, and things slow down substantially. The days will move by slower as the haze of uncertainty thickens, and you will feel each minute lengthen as familiar routines fade away into the background.

Remember that when you enter one of those yellow circles above, you enter a space where time expands, and things slow down substantially. The days will move by slower as the haze of uncertainty thickens, and you will feel each minute lengthen as familiar routines fade away into the background.

It is here where your decisions will matter most.

The majority of progress is determined by the minority of choices you make. Setbacks, such as the one we’re all in the midst of, is where we lay down the foundation for how things will move once the dust settles. It’s not the years of continual progress that builds our view of the world, but our response to rapid pushbacks that does.

This is summarized wonderfully in a tweet by Angela Jiang:

Measure experience in exposure to shocks rather than years.

When our comfortable bubbles are rocked to their core, this is where the capacity for reflection is needed the most. While shocks may introduce the fear of losing scarce resources, it’s only fitting that the most precious resource we have – our time – increases in abundance during these moments.

So use this resource wisely while you can. It’s only inevitable that your future self will thank you for it.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts:

Finding Peace Within the Pandemic