How to Calm the Anxious Brain

Another Note: This post is long. If you prefer to print it out or read it offline, you can grab a nicely formatted PDF of it by becoming a patron.

The human mind is like a pair of bifocals. It has the incredible ability to see far off into the distance, but it can also be ridiculously short-sighted at the same time.

We possess the incredible intelligence and work ethic to build rockets that will eventually take us to Mars, but can’t agree on simple measures that will prevent temperature increases here today on Earth.

We understand what it means to make sacrifices to build wealth for future generations, but we do it at the expense of spending meaningful time with our loved ones today.

These struggles remain at the core of our being, and we’ve spent thousands and thousands of years trying to navigate this central dichotomy.

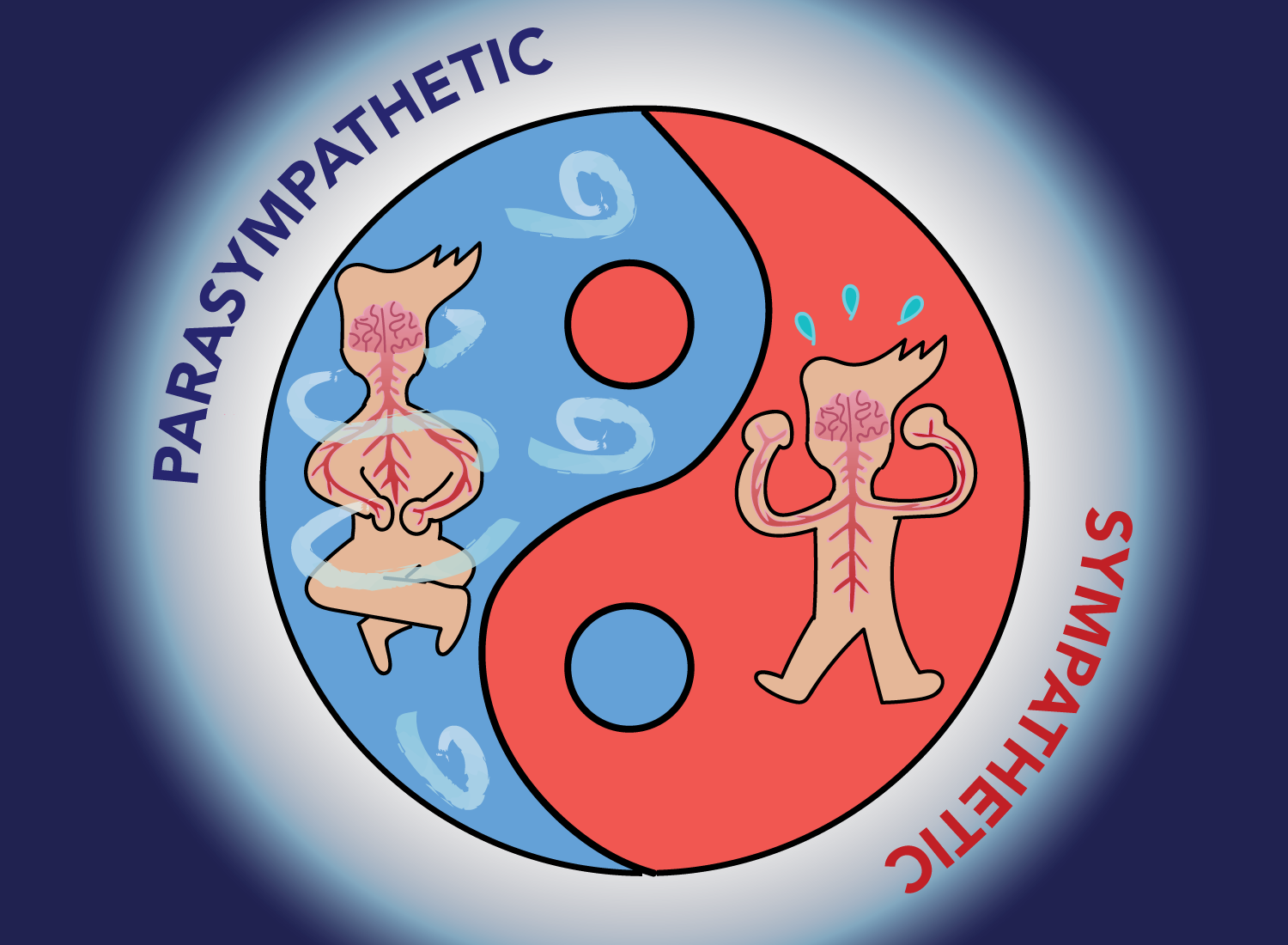

We’ve created mythical stories, religious values, and governmental institutions based upon the premise that for every hero there’s a villain, for every yin there’s a yang, and for every ideology there’s a counter-argument. This “push and pull” dynamic is seen everywhere, but nowhere is it more apparent than the ongoing battle between our impulsive tendencies and our rational groundedness.

This constant struggle sets the stage for almost everything we do in life – even the simple act of getting up to go to work is your rationality governing the impulse to stay in and sleep all day. Sadly, our default setting is to go with the result that seems most pleasurable now, but reveals its consequences later. As author James Clear puts it, “the costs of your good habits are in the present. The costs of your bad habits are in the future.”

As I researched the structure of the human brain to prepare for this two-part series on anxiety disorders, it became strikingly clear to me why this struggle exists.

It’s built right into the anatomy our brains.

In Part 1, I introduced the More To That map of the human brain, which took this super complex, mushy goo of cells and neurons riding in our heads:

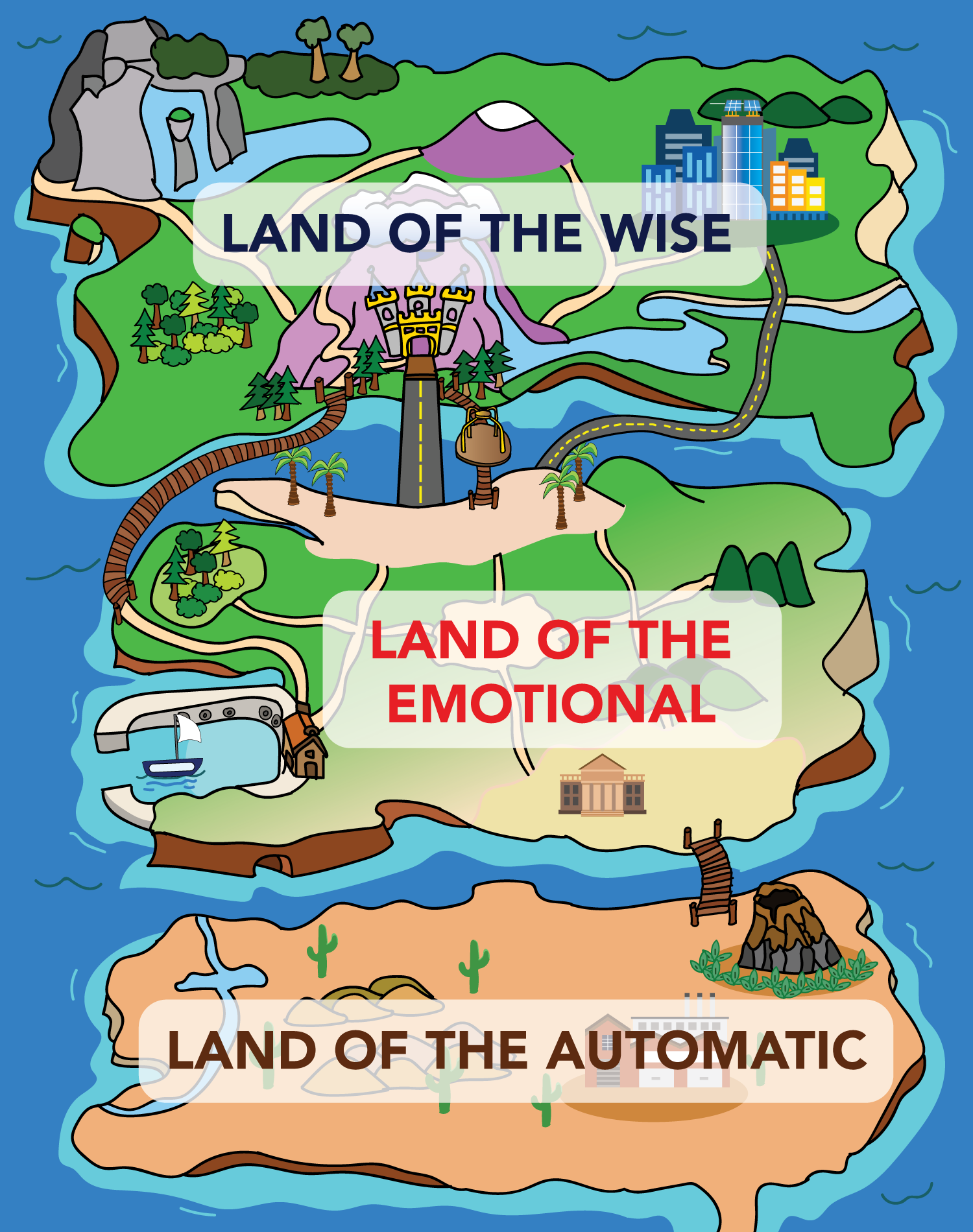

And turned it into this:

A little more colorful, yes?

Of course, this ridiculously simplified map doesn’t belong anywhere near a collegiate neuroscience course, but I think it does a good job in detailing the three (metaphorical) layers of the human brain.

Adapted from Paul MacLean’s triune brain model, it separates the brain into three interconnected continents. So far, we’ve covered the first two lands quite extensively:

(1) The Land of the Automatic, which is commonly referred to as the reptilian part of the human brain. It is the most ancient part of our brains, and it mediates automatic functions like breathing, chewing, swallowing, temperature control, etc. The physiological sensations of the stress response, or the sympathetic nervous system, are caused by adrenaline and norepinephrine releases in this land.

(2) The Land of the Emotional, which is known as the limbic system. This part of the brain is what we jokingly refer to as our “monkey mind”, and is largely responsible for processing emotion and assigning context to them. It is what takes in external stimuli and alerts the body of what to do next, and is the land that governs emotions like fear, horniness, pleasure, or any other thing that our primate cousins would be immediately down with.1

These first two lands are largely responsible for the impulsive behaviors that prioritize pleasure over practicality. If it feels good to do now, then it won’t matter what the consequences are – they’ll just deal with them later. As you can imagine, these two lands throw some epic parties for the present moment, but they’re not much use in dealing with the massive hangover the next morning.

These two lands are also responsible for the troubling physiological sensations, consistent fear, and avoidance behaviors that result from many anxiety disorders. If left unregulated and untreated, the collective force of these lands can lead to unmanageable levels of distress, so it’s important to understand how we can use the power of our brain to turn down the volume of these raucous lands.

To do this, let’s pick up where we left off and head up to the final land of the brain.

The Land of the Wise

The Land of the Wise, more commonly referred to as the cortex, is the outer layer of the brain that holds the capacity for logical analysis, working memory, and abstract thought. It is the captain of the brain, receiving messages from the other lands and keeping them in line as well.

When people refer to the famous left and right hemispheres of the brain, they are generally referring to the lateralization (or division) in this outer layer. The left side is largely responsible for language processing, verbal comprehension, and analytical thought, while the right side governs important things like emotional thought, intuition, and creativity.2

But instead of viewing the Land of the Wise from a left-to-right perspective, we’re going to focus primarily on one area of it: the frontal cortex.

The frontal cortex is arguably the most interesting part of the human brain, and it is responsible for all the rational behavior we exhibit that makes life a rewarding experience. It is responsible for long-term planning, emotional regulation, gratification postponement – basically all the qualities a human being needs to be a productive and functioning member of society.

Robert Sapolsky, professor of biology and neuroscience at Stanford, sums up the entire role of the frontal cortex quite nicely: “the frontal cortex makes you do the harder thing when it’s the right thing to do.”

It’s no surprise that it’s the most recently evolved brain region in humans, but is not fully formed in our primate cousins. Interestingly enough, the frontal cortex is the last part of the brain to fully mature and go online – this doesn’t happen until our mid-twenties, which explains a lot of the stupid shit we did in our younger days.

While the frontal cortex is awesome, there’s a central character living here that represents the true sage of the brain. It resides in the very front of this area, and is the newest part of the frontal cortex, meaning that it’s the most advanced part of the already most advanced part of the human brain.

Say hi to the guru of the brain world:

The prefrontal cortex, or the PFC.

This wise sage’s primary role is to do the hard work of choosing between conflicting options. And most of the time, the conflict is between choosing an option driven heavily by cognition or one driven by primarily by emotions.

The PFC is the thing that tells us to do our work instead of messing around, to keep in a fart instead of letting it out in front of your boss, and to chill out when unnecessary stress comes your way.

It has the power to exert control over the two lower lands, using its executive position to “talk down” heightened emotional states and even slow neural activity. Even something simple like taking a deep breath is your PFC at work – this action interrupts the autonomous breathing pattern of the Land of the Automatic to create a calming sensation through a long, mindful breath.

For this reason, the PFC is really important in the regulation and treatment of anxiety disorders. It is the target of many applications of psychotherapy, many of which we will get into a bit later. Through the continuous exercising of its executive functions, it can gradually learn how to reframe events that were previously learned as threats, and calm the amygdala in the process.

The fact that something as wise as the prefrontal cortex lives alongside something as unpredictable as the amygdala is a testament to the inescapable battle between our impulsivity and rationality. This struggle is enrooted in the core essence of who we are, right down to our own biology. Much of human existence is about striking the right balance between the two – if we allow the Land of Emotional to have complete, 100% control over us, we will likely end up destitute and homeless. On the other hand, if we allow the Land of the Wise to have complete control, we won’t know what it’s like to have any fun. So the key here is to pay attention to the moments in which your impulses are guiding you to the right place, and the times in which your rationality is telling you otherwise.

In the case of anxiety disorders, however, the two lower lands of emotion and automation have too much governance over how the mind works. The fear response to thoughts and external stimuli are grossly overexaggerated in the anxious brain, and the sympathetic nervous system is activated far too frequently as a result.

So we need the Land of the Wise (specifically, the PFC) to come in and assert its inherited dominance and control over the brain world. The question is… how exactly does it do this, and how come it doesn’t work as frequently as we want it to? To understand this, we’re going to delve back into the anxious brain of our central character from Part 1.

Let’s all say hi again to our friend, Sam.

Sam has social anxiety disorder (abbreviated as “SAD”), and in Part 1, we detailed how a chance encounter with a stranger named Sharon automatically triggered an intense stress response in him. We took a brief tour of how this external stimulus was interpreted by various players in the Land of the Emotional, which ultimately led to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system via the Land of the Automatic.

But despite the elevated heart rate, flushing of the face, and the flurry of uncomfortable sensations he’s experiencing, why doesn’t Sam react to Sharon’s presence by literally fleeing the moment she talks to him? Why does he continue to stick around, trying to carry the conversation forward despite his body telling him to get the fuck out of there?

Well, that’s the power of the PFC at work.

While many sufferers of social anxiety will do their best to avoid social situations, it is rare that one will literally run away in fear when approached by an acquaintance or someone they don’t know very well. They may exhibit exceptional shyness by avoiding eye contact or remaining silent through the conversation, but the sounding of the amygdala’s alarm system is not often met with literal flight in these situations.3

Fortunately the limbic system, or what we refer to as the Land of the Emotional, does not have free reign over the brain – if it did, then we would be like dogs, running away the moment something remotely frightening happens. But because the Land of the Wise has the power to exert its control over it, the PFC has the ability to defy what the other lands are screaming for us to do.

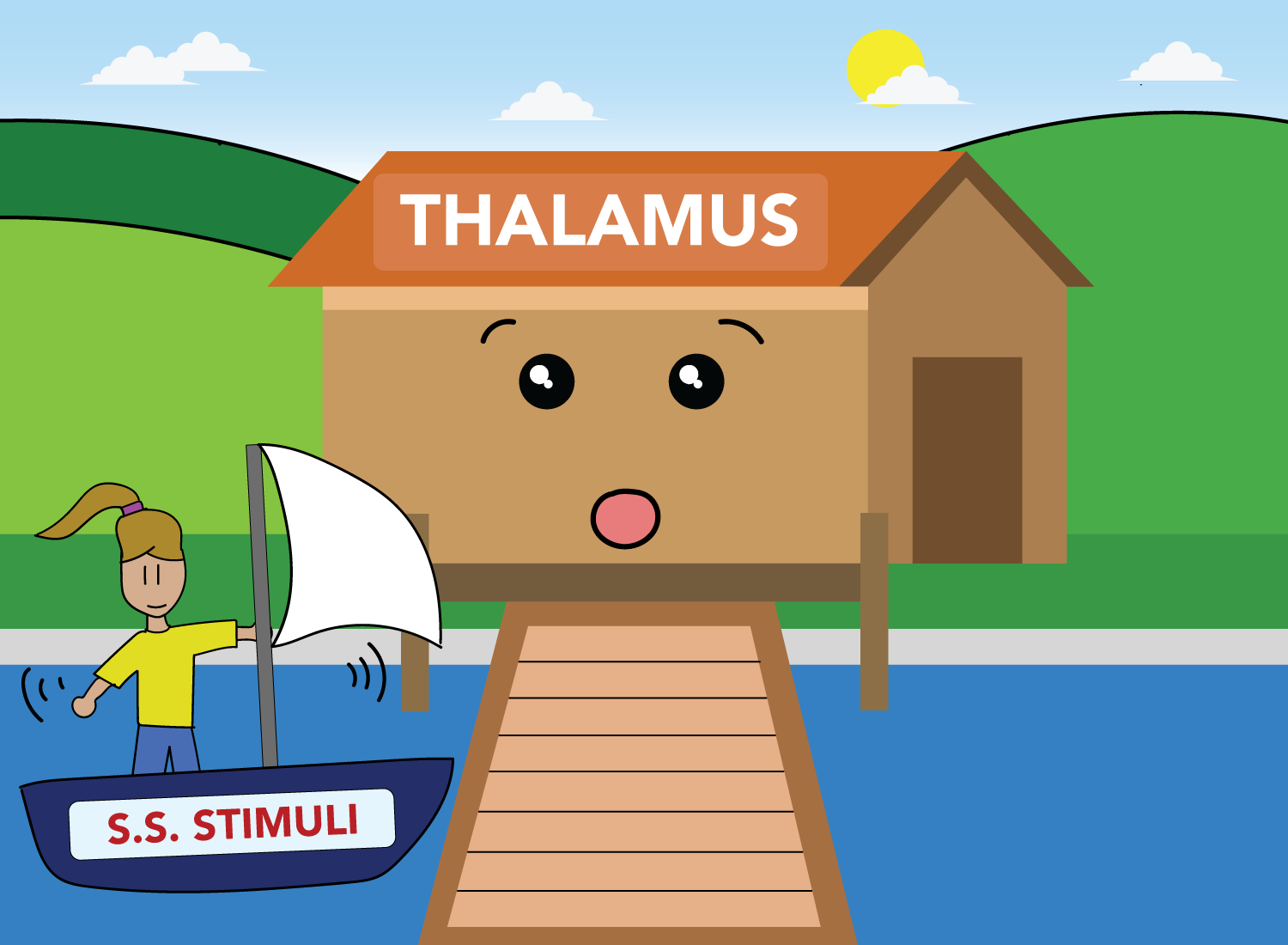

To understand how exactly this happens, we must rewind to the very beginning, when the S.S. Stimuli (the boat that houses Sharon as an external stimulus) first arrives at the port of the thalamus in the Land of the Emotional.

Upon the stimulus’ arrival, the thalamus instantaneously sends this information to the amygdala for fast response. Sam’s amygdala immediately perceives Sharon as a threat, which kicks off a chain of events that ultimately leads to the stress response. We already discussed all this in Part 1, so we’re not getting into it here.

But here’s the thing we didn’t go over yet.

Upon receipt of the stimulus, the thalamus also sends a second message, but this time up to the Land of the Wise – specifically, to our sage, the PFC. However, since the connecting pathway to the PFC is literally longer, the amygdala gets thalamic input first.

So this means that the sensitive warning system of the amygdala is triggered before the PFC even has the chance to interpret the stimulus itself.

This is why when a friend decides to scare the shit out of you by hiding around the corner, the very first thing you feel is intense bodily sensation, powered by the adrenaline and norepinephrine release triggering the fight-or-flight response.

It is only after this shittiness that the PFC receives the sensory information, and determines that it’s just your friend being an asshole, so there’s no need to actually be afraid.

I find it absolutely fascinating that it’s due to the literal length of the connecting pathway to the PFC that our rational interpretation of things can’t come first. In some alternate universe, maybe natural selection reversed the neurological wiring, and something like this is happening:

But that’s not the universe that you nor I are living in, so we’ll have to leave that be.

Instead, let’s go back to Sam, and see what’s happening in his world.

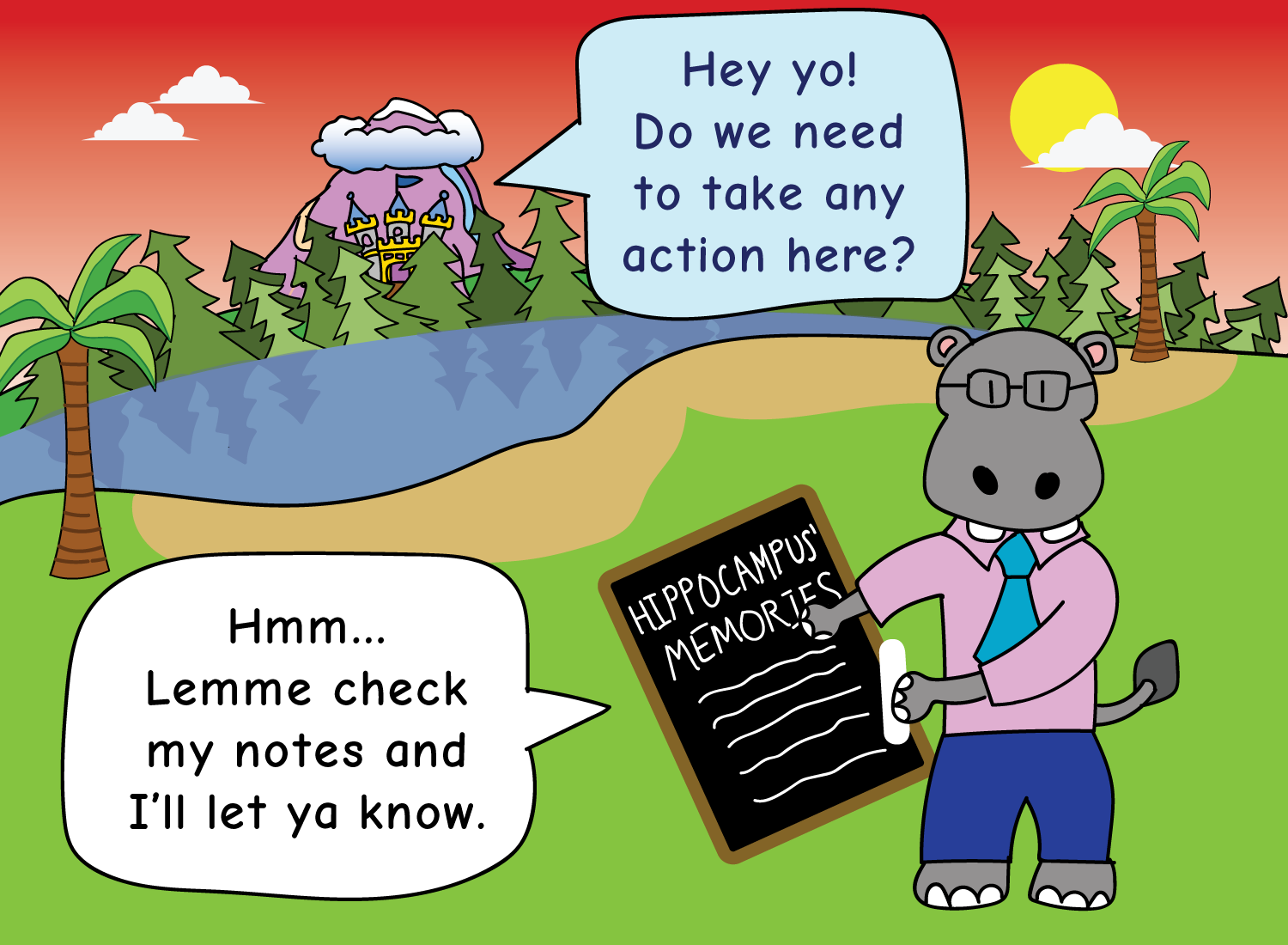

At this moment, his body is experiencing significant discomfort due to the amygdala’s immediate processing of Sharon as a threat. But the PFC has also received thalamic input from the situation, and is asking itself one all-important question:

“Is it necessary to be afraid or not?”

To answer this question, the PFC will consult with our memory record-keeper, the hippocampus, to determine the context of the sensory information, and compare it with long-term memory to determine if immediate action is required.

After a quick analysis of the situation, Sam’s PFC makes the determination that while social situations have brought about stress, there is no need for a life-threatening flight response. Once this conclusion has been made, it needs to pass this message back down to the amygdala so its alarm can be moderated.4

However, in order to explain how the PFC exerts its influence over the amygdala, there’s an important bridge we need to introduce to the story. Its name is the anterior cingulate gyrus (abbreviated as the “ACG,” which is a subsection of the anterior cingulate cortex) and it carries many functions, some of which include the connection of reward centers with the hippocampus and the processing of sensory and motor information.

For our purposes though, we will focus on one essential function. The ACG is what allows for the smooth transition between cognition and emotion. It is the bridge that allows for cognitive flexibility, providing our brain with the openness to move from one idea to another to find the most preferable option.

In the context our map, I imagine it to look like a rotating circular bridge connecting the PFC (in the Land of the Wise) to the amygdala (in the Land of the Emotional):

When the PFC determines that an emotion-driven flight response is not necessary, it can go through the ACG bridge to modulate the amygdala and calm it down. The amygdala will then be able to assess that this cognitive response is the appropriate option to take, and will try to unlearn the initial fear surrounding the stimulus.

Whenever you’re in a fearful situation with high emotional arousal (“I’m scared I will die of a plane crash!”) and you’re able to use a cognitive response to calm it down (“The odds of dying in a plane crash are MUCH lower than if I were to get into a car, so it doesn’t make sense to feel this dread”), that’s the ACG allowing you to make that shift between emotion and cognition.

The ACG is really important in the gradual unlearning of fear in anxiety disorders, and one of the keys to a healthy ACG is the neurotransmitter serotonin.

I’m sure you’ve heard of this guy before, but the simplest way to think about serotonin is to equate it with regulation. It regulates internal body temperature, appetite, impulse control, mood, perception, and a bunch of other important stuff for you to function like a normal human creature. It is also involved in the ability to recognize reward through various experiences, and allows the PFC to create positive cognitive interpretations of situations – in other words, it helps produce the feeling of optimism.

But most importantly for us, it allows for smooth functioning of the anterior cingulate gyrus. The thing about the ACG is that if left unregulated, it has the tendency to spin around wildly, like an unhinged merry-go-around caught in the middle of a windstorm.

When this happens, emotionally-charged thoughts get caught in this constant loop, as the PFC is unable to use the ACG properly to tell the amygdala to chill the fuck out. The thoughts then become ruminative, and it becomes very difficult for the brain to shift toward reasonable patterns of thought that make way more sense.

This is a prominent feature of people with Generalized Anxiety Disorder, where intense and destructive worry can result from unreasonable thoughts. For example, let’s say you were at work and you emailed a document to your boss that contained a minor error. The reasonable response would be to simply dismiss that error as a minor one and go about your day.

However, for someone with intense generalized anxiety, he could think that the error would be a sign of his gross incompetence, leading his boss to fire him, leaving him without a means to support his family, which will ultimately end in destitution and eventual homelessness. As implausible as this sounds, this negative thought can continue to loop around and grow, causing deeply unpleasant cycles of worry and fear that just won’t go away.

This is the result of an unhinged, overreactive anterior cingulate gyrus that has taken this thought and latched onto it, preventing the PFC from properly evaluating it, offering a better solution, and calming the amygdala down. Even if he inherently understands that the worry is silly, the physiological sensations resulting from the stress response continue, which further exacerbates his anxiety and legitimizes the thought to him.5

For the ACG to function properly, it needs to be regulated, and the way this happens is through a healthy presence of serotonin. I like to think of serotonin as the construction workers that steady the circular merry-go-around-like bridge, bringing it down to a nice pace where thoughts, feedback, and neural responses can seamlessly travel between the amygdala and the PFC. This allows for the smooth transition between emotion and cognition, and anxiety-inducing thoughts have a higher likelihood of being dismissed upon arrival.

A healthy level of serotonin in the brain is crucial, and one reliable way to boost it naturally is through consistent exercise (it also helps to do it when the sun is out as well). Not only does exercise increase blood flow in the PFC to allow for greater control over the brain, it helps to produce the serotonin required to open up the communication channel between the PFC and the amygdala. If you’ve had a nice, sweat-producing workout recently, you will likely have felt a sense of calm afterward, accompanied by a degree of mental clarity.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again:

While exercise is important for one’s physical health, it produces an even greater benefit for one’s mental health as well.

However, just telling Sam to exercise more often is some pretty generic, unhelpful advice. Chances are that if you’re some form of human being, exercise is a good thing for you. Telling an anxiety-ridden person that exercise will make him feel better is just as helpful as telling a college student that studying will be a reliable way to get good grades. While things like frequent exercise and psychoeducation (learning about the neurobiological roots of anxiety disorders) are helpful in coping with anxiety, they are just small parts of a robust framework required for sustainable change.

Now that we’ve introduced and explored the three lands of the human brain, this is a good time to delve into some of the existing frameworks that help to answer this all-important question:

What can I do to feel less anxious in way that lasts?

This is a loaded question, but one that is ultimately answerable. Using what we’ve learned so far about the inner workings of the anxious brain, let’s explore the two prominent therapies that exist for anxiety disorders today:

(1) cognitive behavioral therapy, and

(2) exposure therapy.

While these two forms of therapy can be conducted individually, using them in conjunction with one another can be highly effective in the treatment of anxiety.6 Using much of what I’ve learned from these two great books – Joseph LeDoux’s Anxious, and Margaret Wehrenberg’s The Anxious Brain – we will delve deeper into what these two forms of therapy look like, and how they work in the context of our brains.

Let’s start with the first one: cognitive behavioral therapy.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

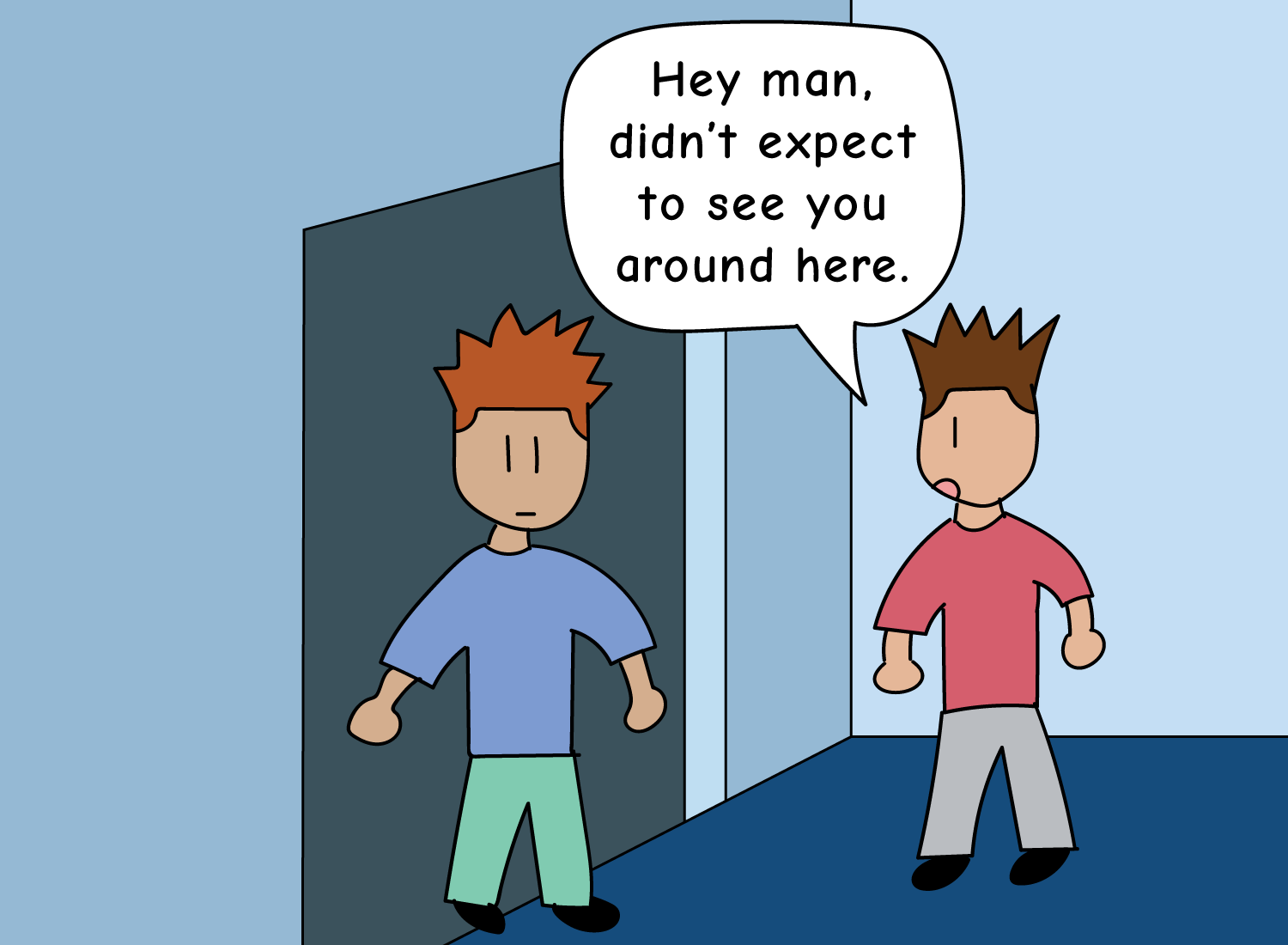

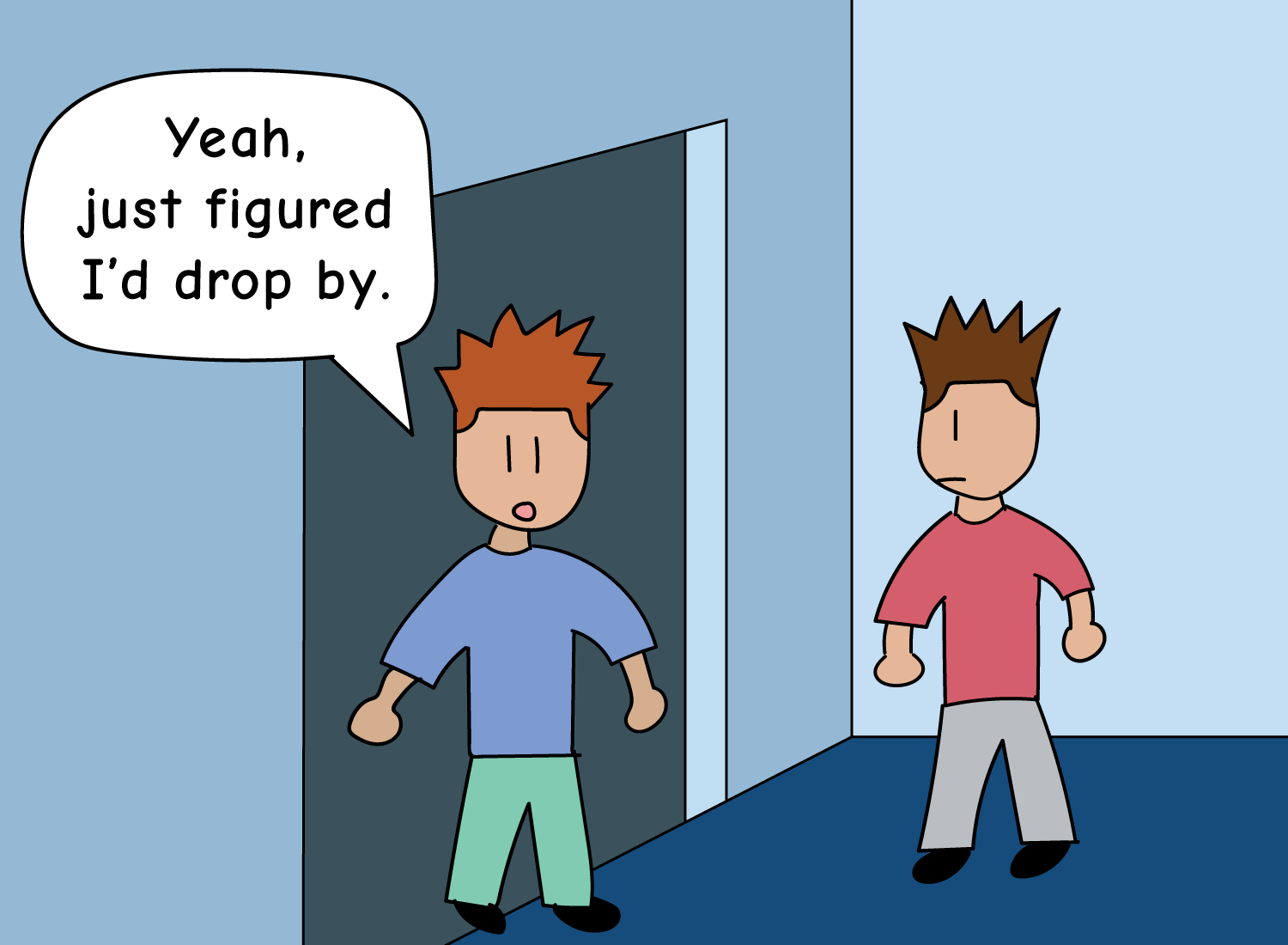

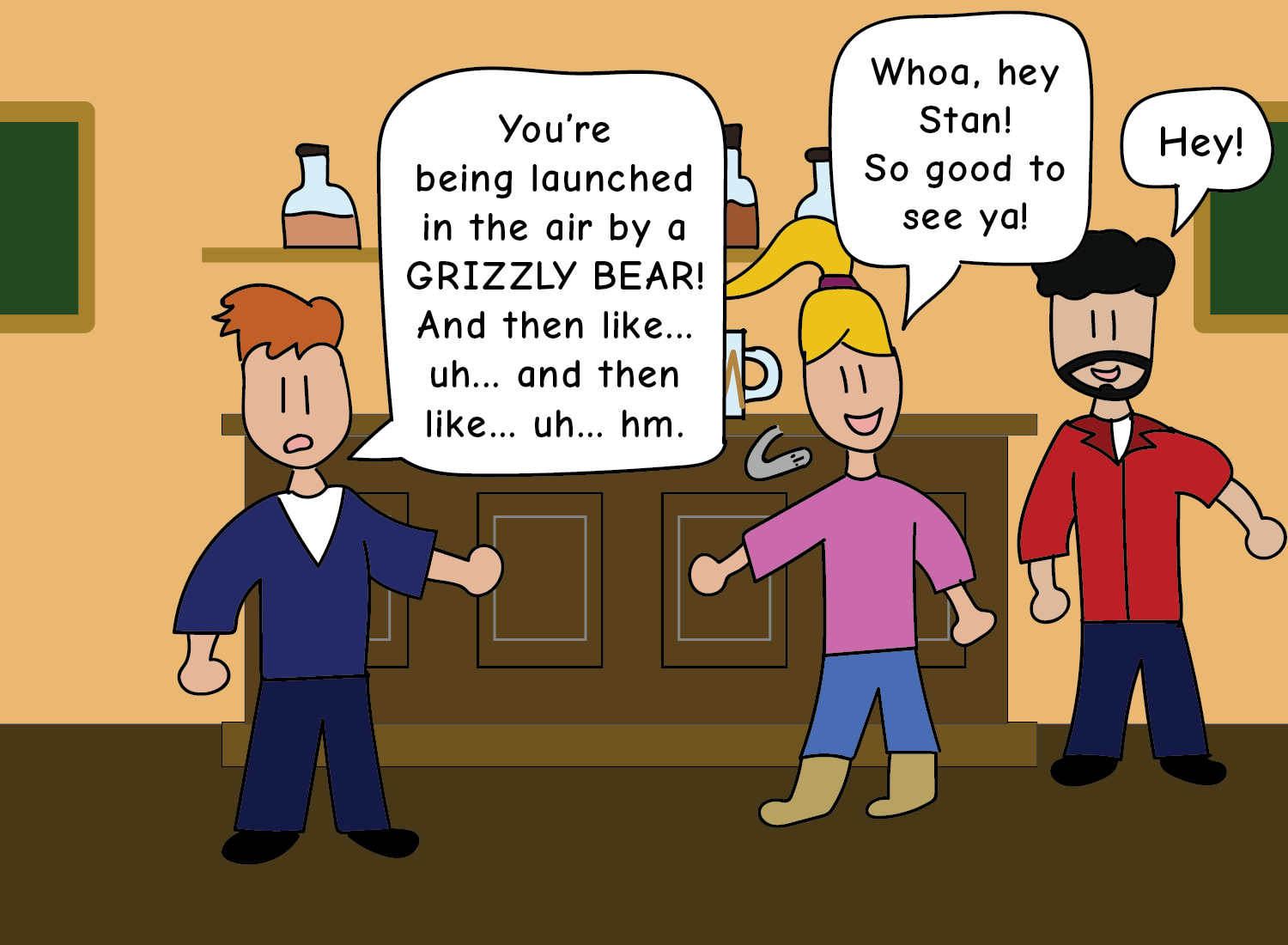

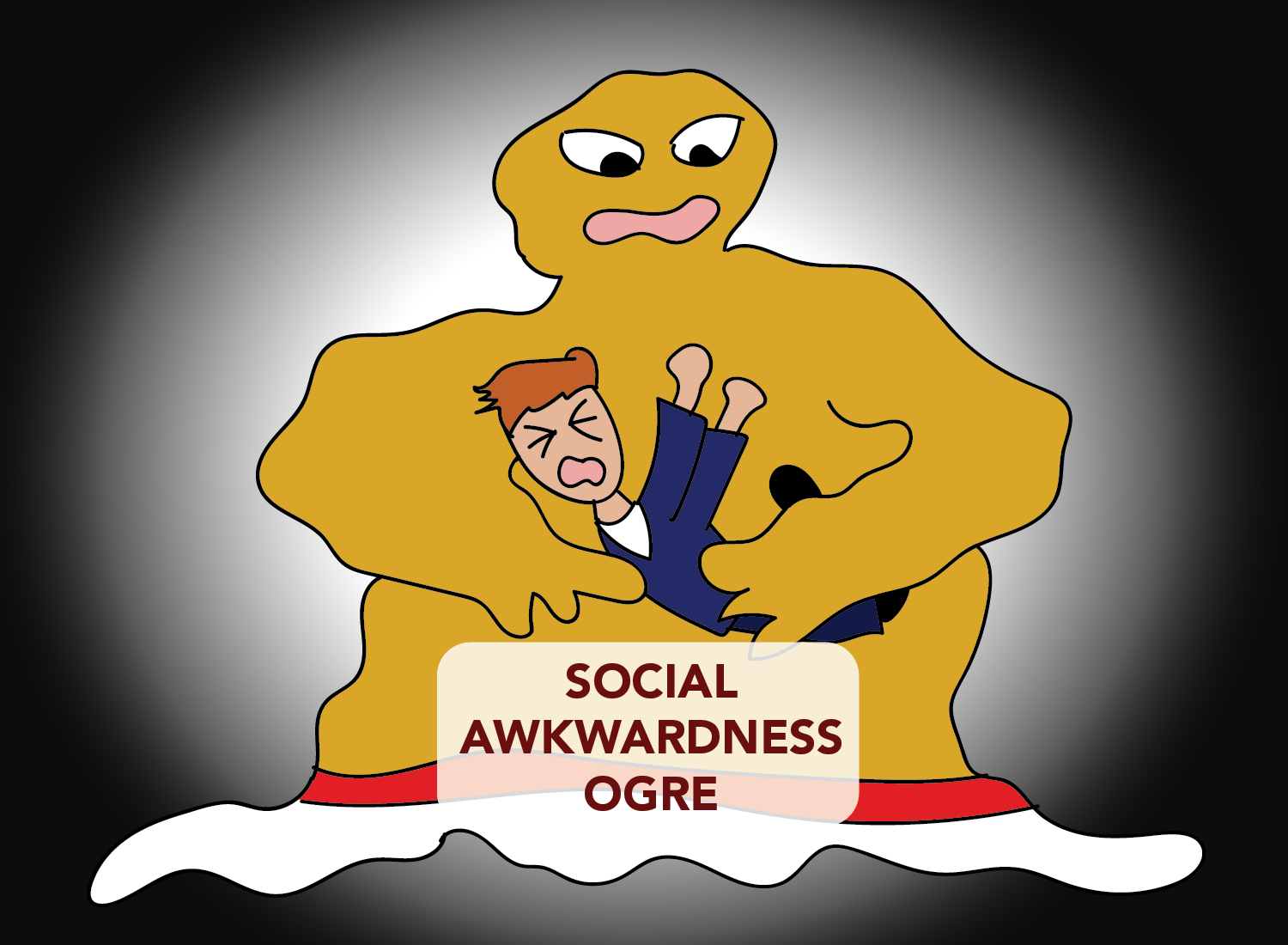

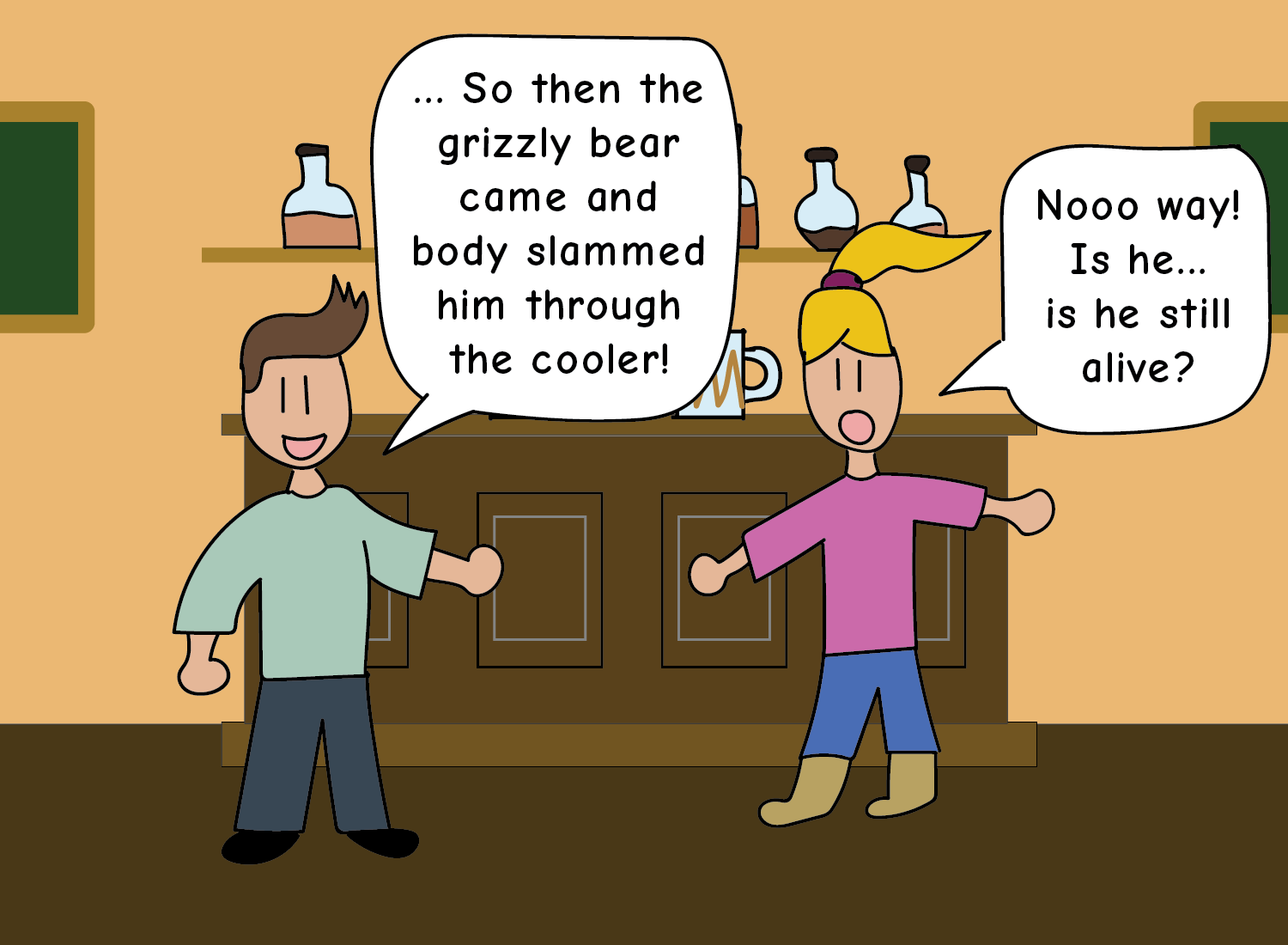

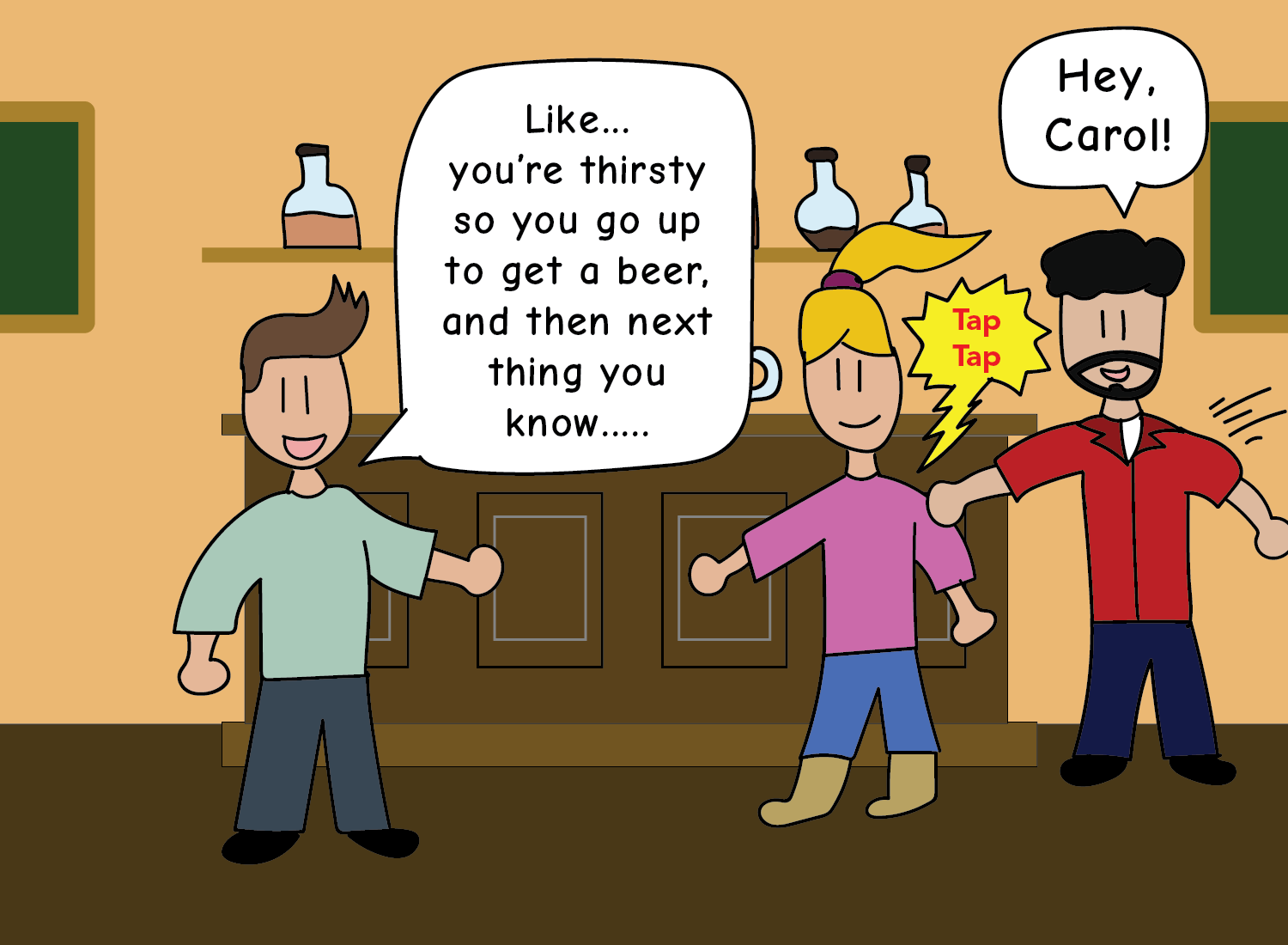

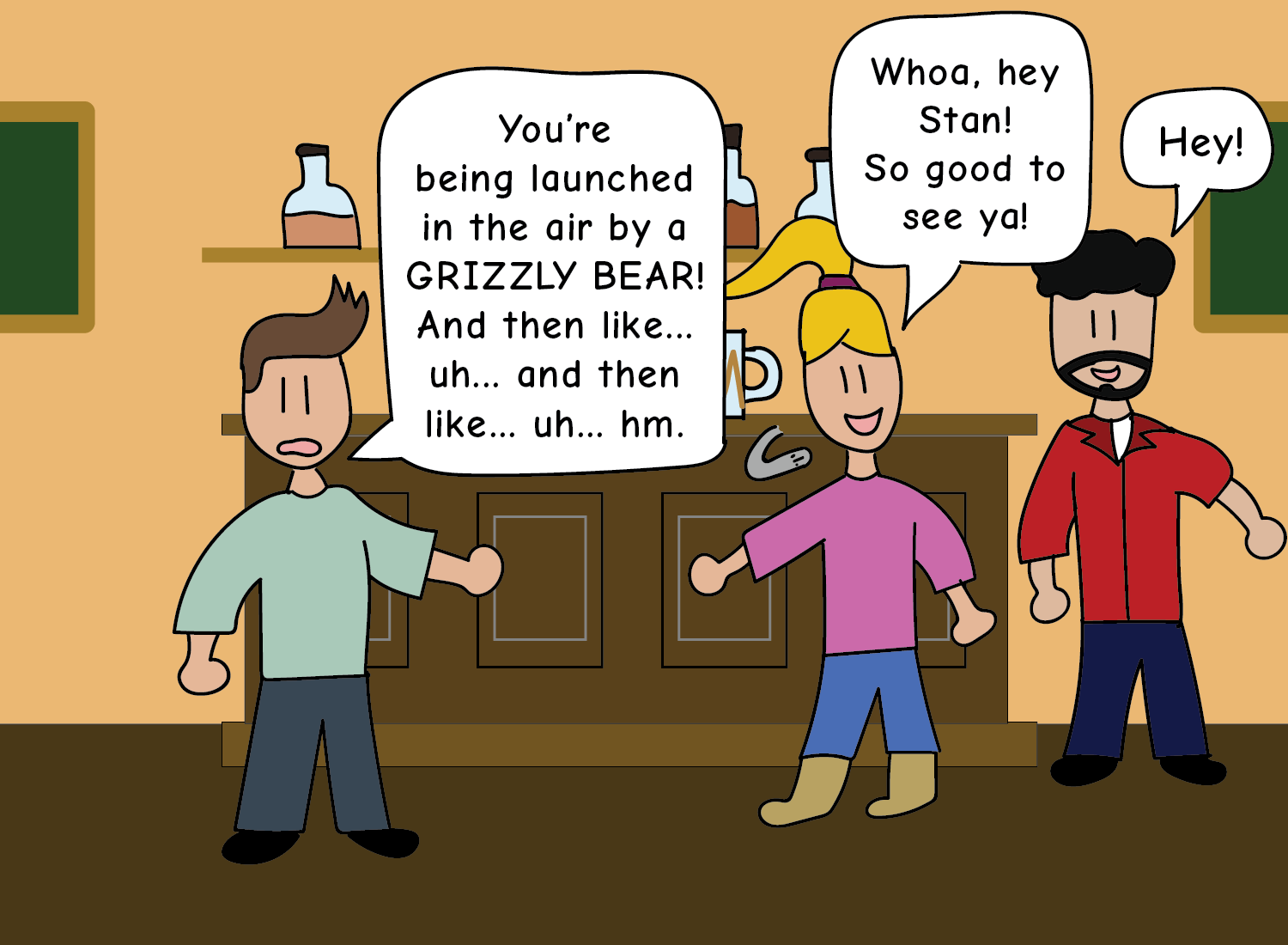

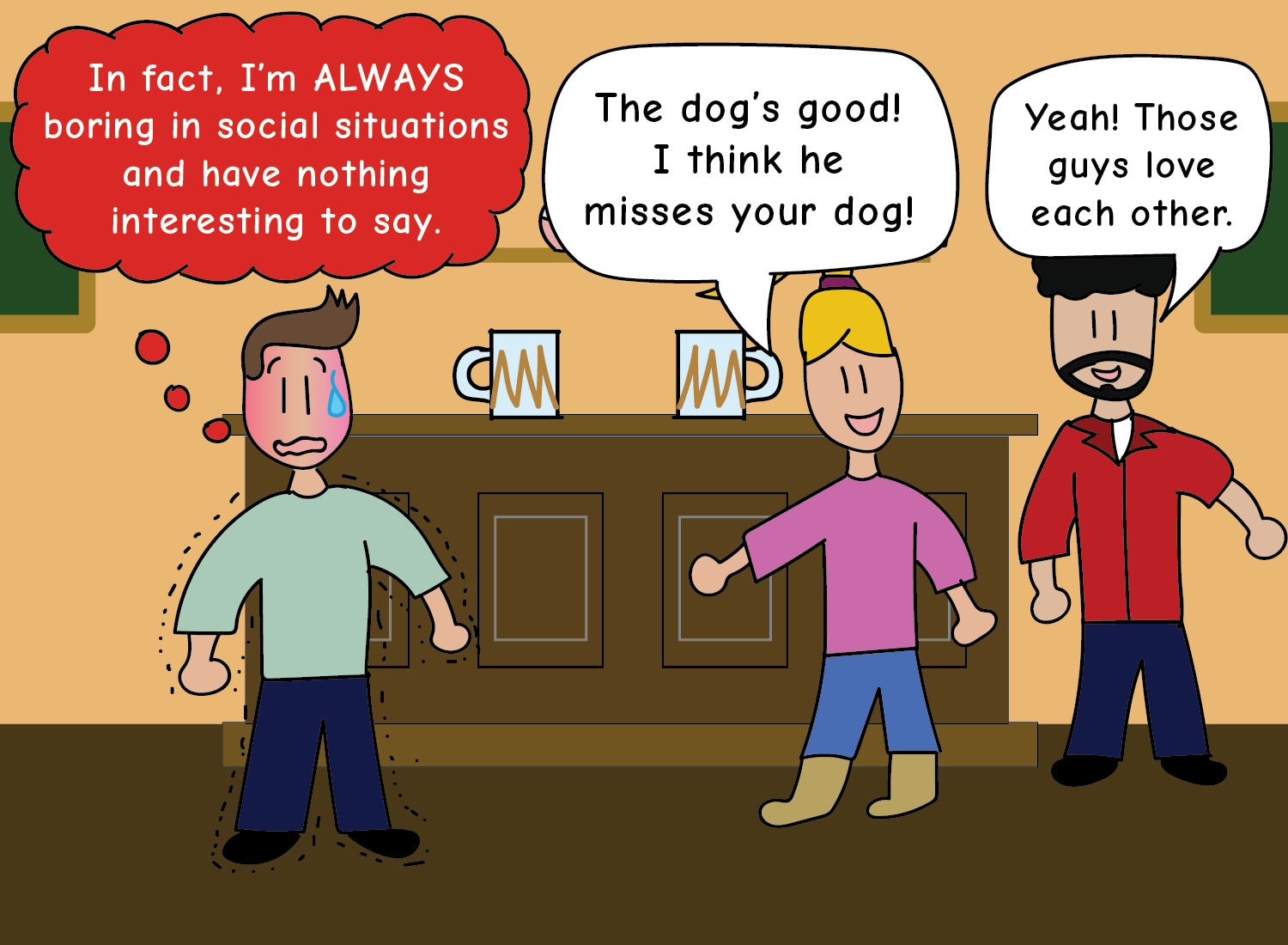

Chances are you’ve been in the orange-haired guy’s situation fairly recently:

It’s a weird feeling.

It’s this feeling of being derailed from a pleasant social interaction and landing into the rough arms of social awkwardness, leaving you temporarily stunned, eyes shifting to something obscure like a nearby wall, with a struggling smile forming on your face.

However, this moment usually ends pretty quickly, and you end up back in conversation again without thinking too much about it.

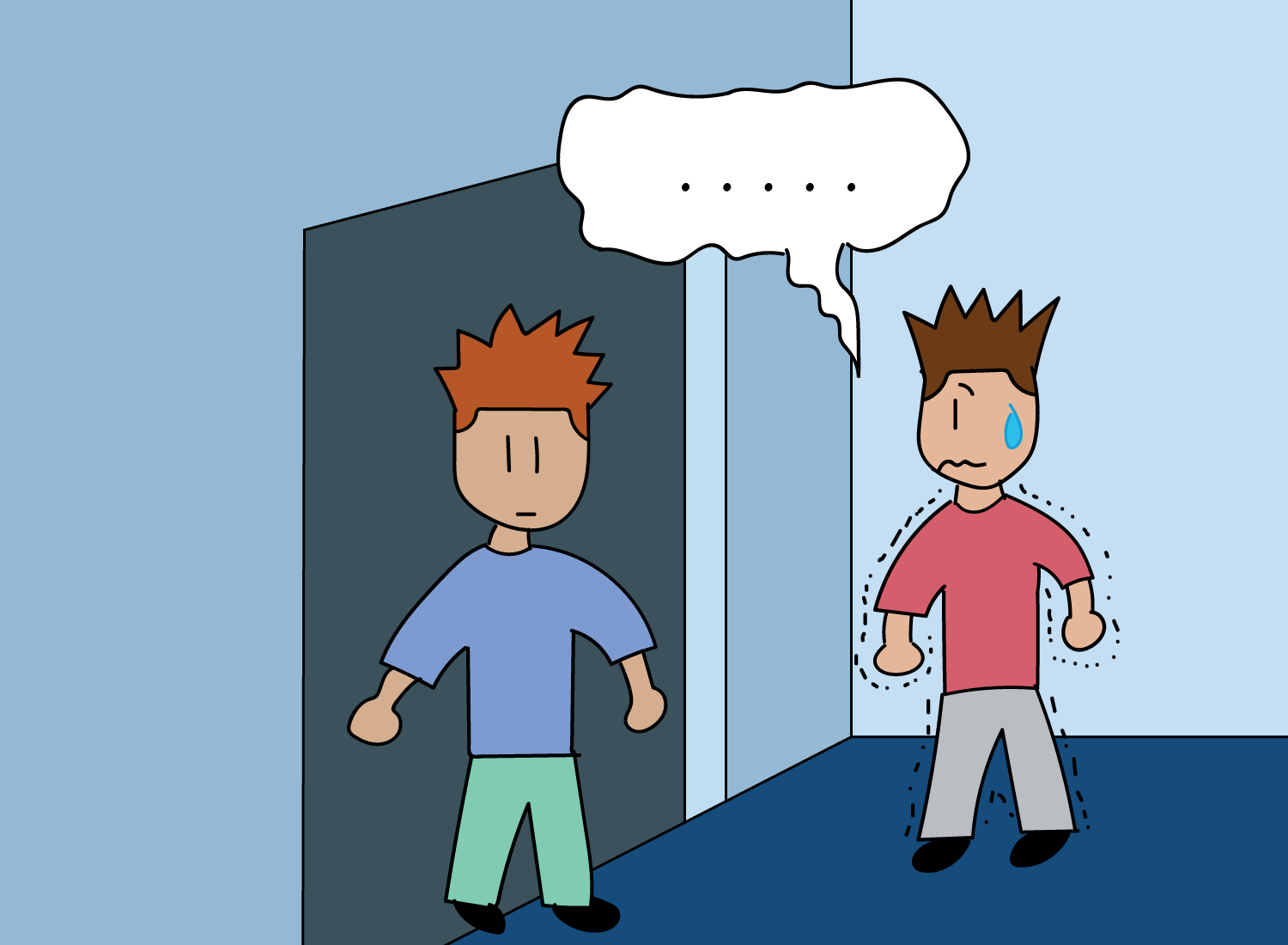

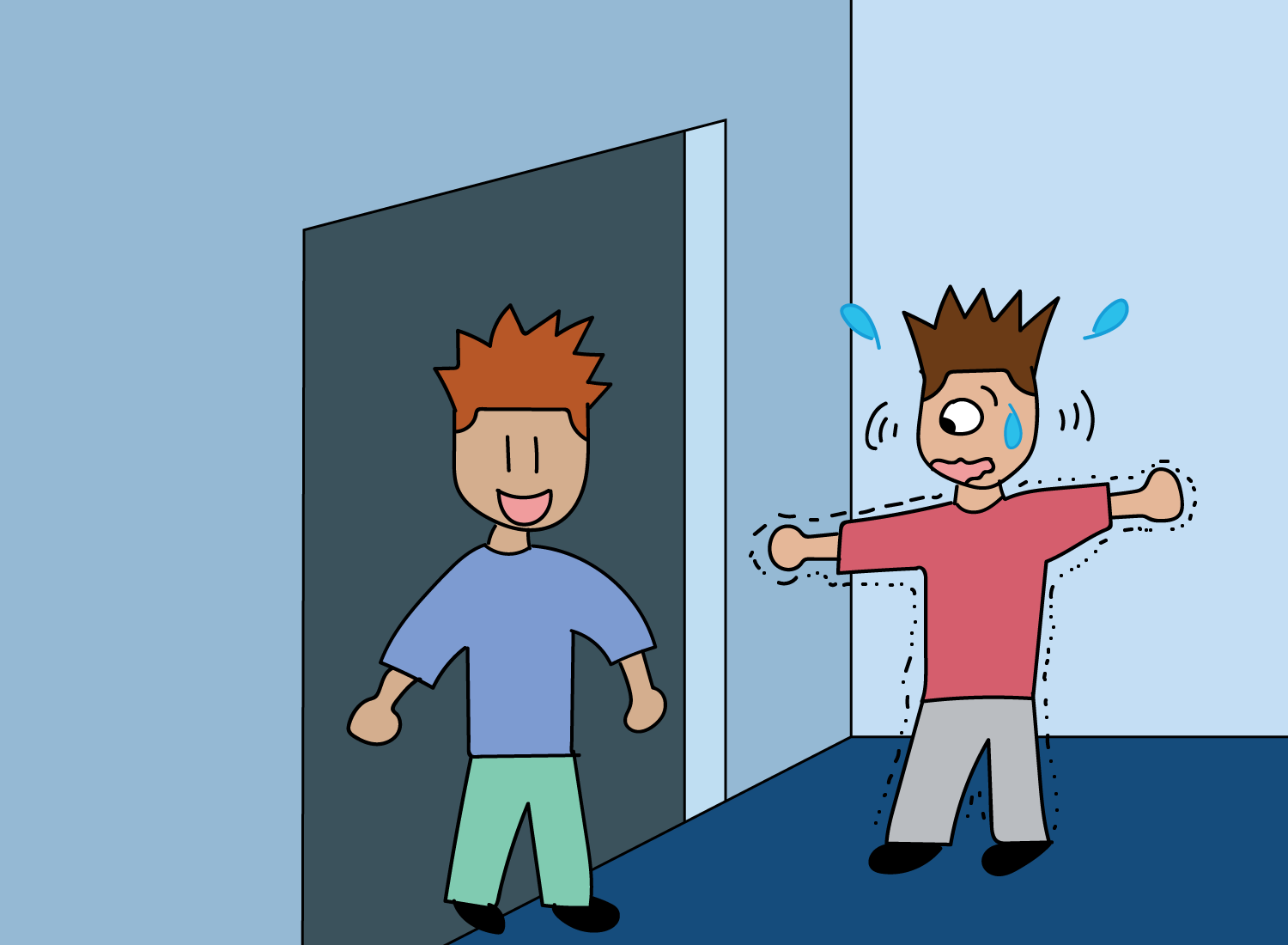

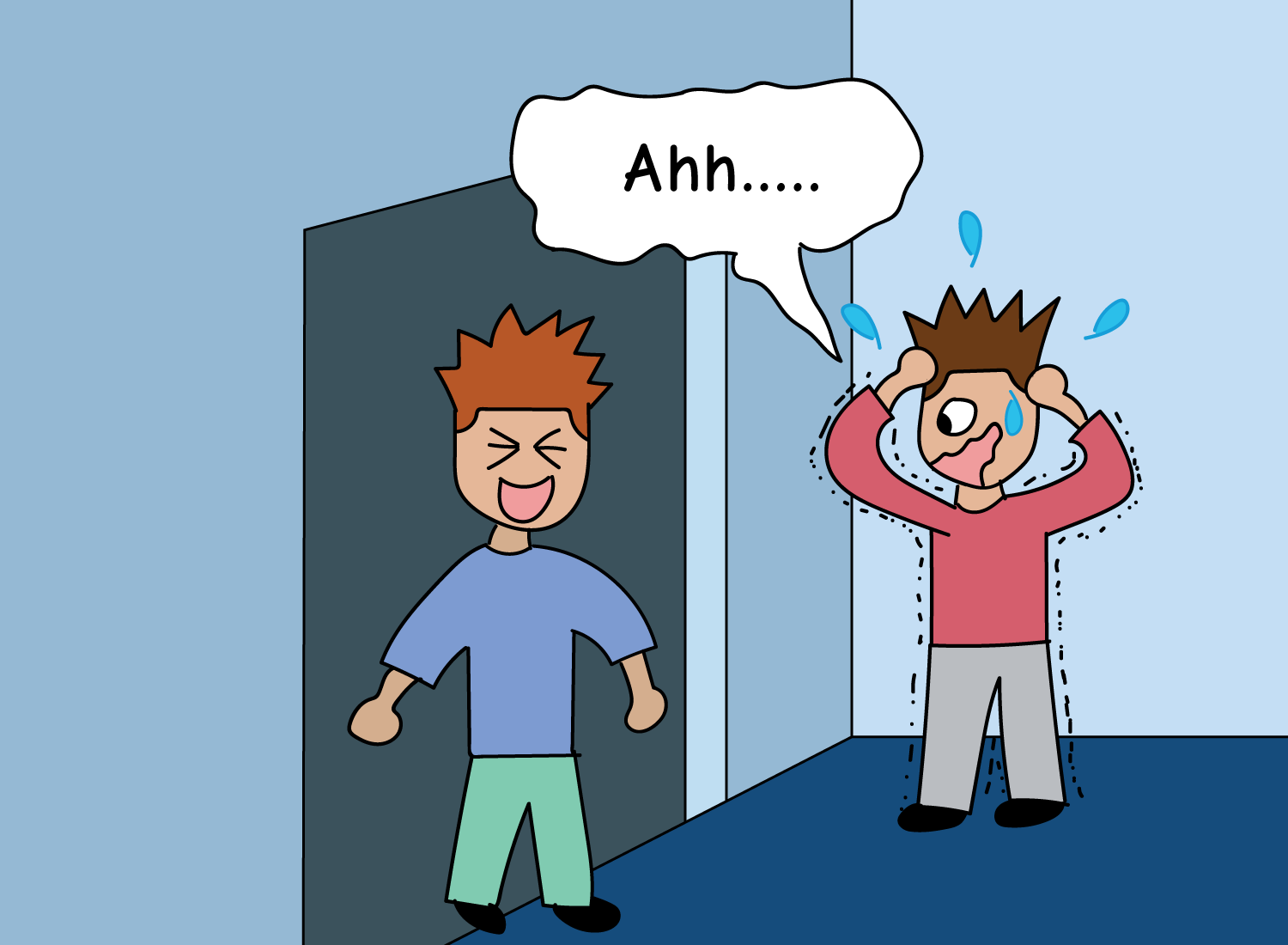

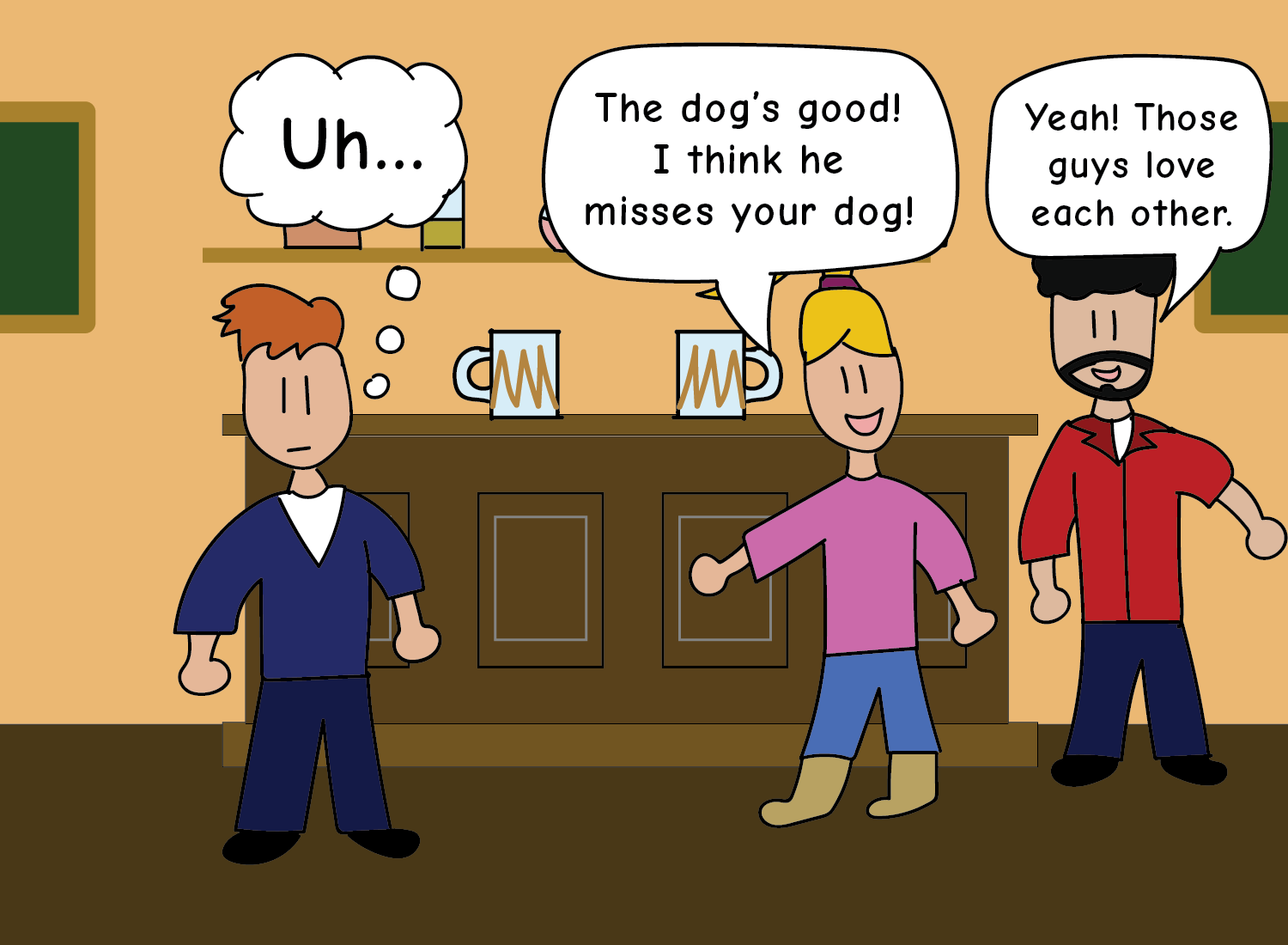

In Sam’s case though, this moment can be hellish, and a barrage of thoughts can quickly populate his mind:

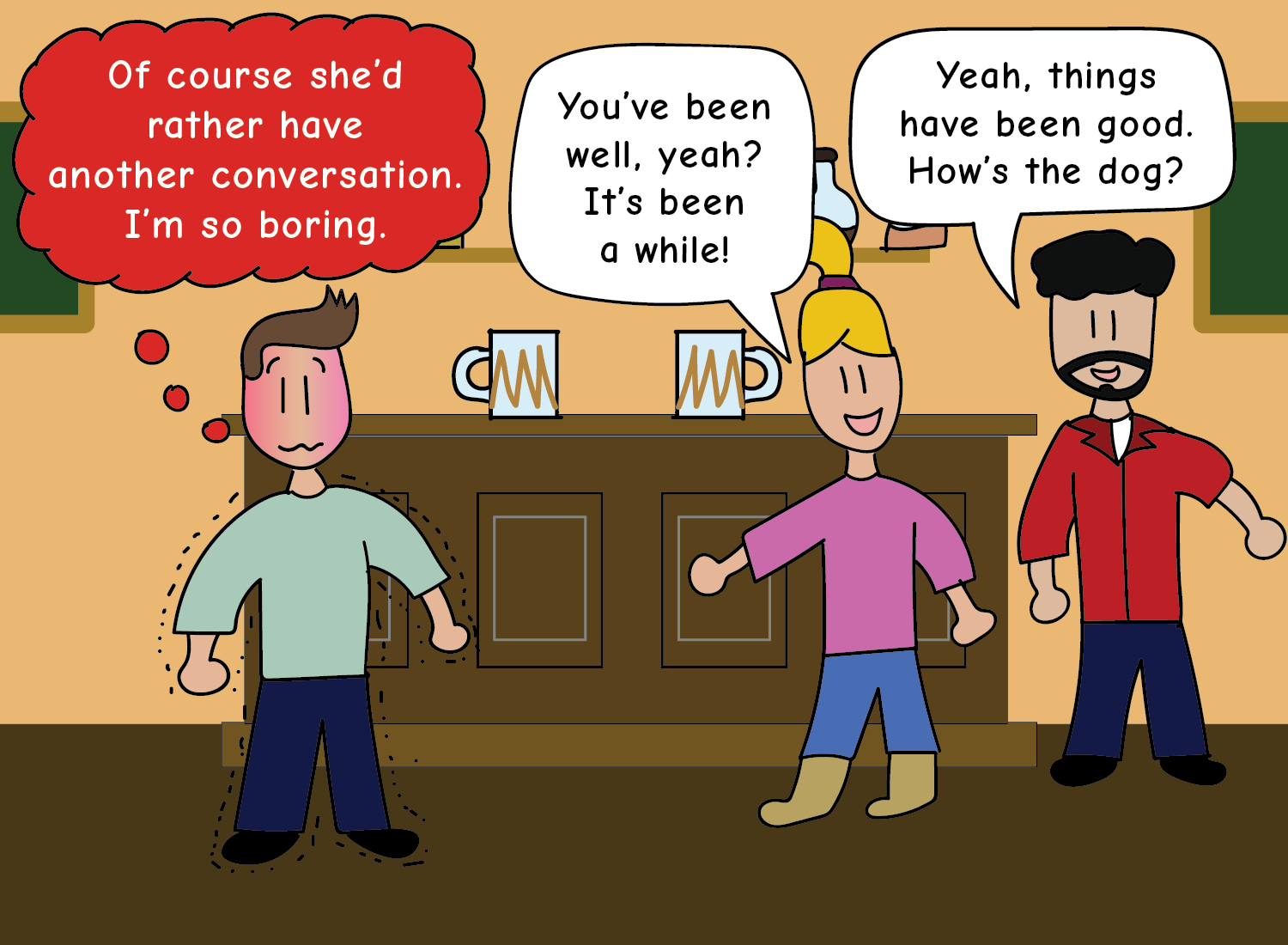

Instead of thinking that his friend was enjoying their conversation but was temporarily distracted by the other person, he immediately thought that she found him boring. This is what is known as a cognitive error, or a “misperception of [an] actual event or situation that has occurred.” A cognitive error, if left unchecked, leads to a false belief that one develops about his relationship with himself, others, and the world.7 In Sam’s case, his cognitive error constructed the false belief that people always found him boring.

Correcting these cognitive errors allows for healthier and more realistic beliefs to take their place. This is the core thesis of cognitive behavioral therapy (abbreviated as “CBT”), which places false beliefs as the origin point for the emotional states of fear and anxiety. According to Aaron Beck, the founder of CBT, if these false beliefs can be properly identified and replaced, then the associated physiological sensations can change, and healthy behavioral shifts can follow accordingly.

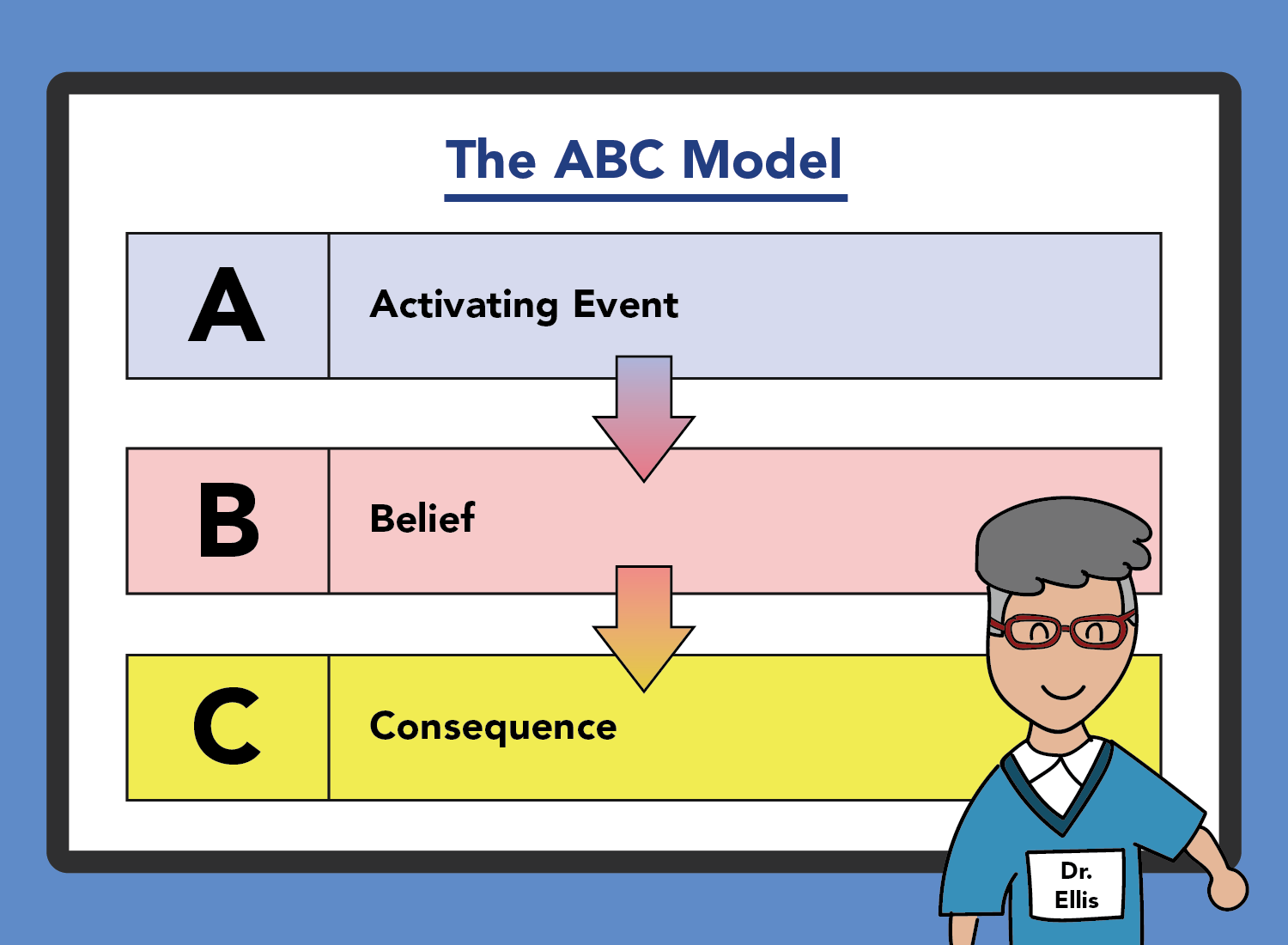

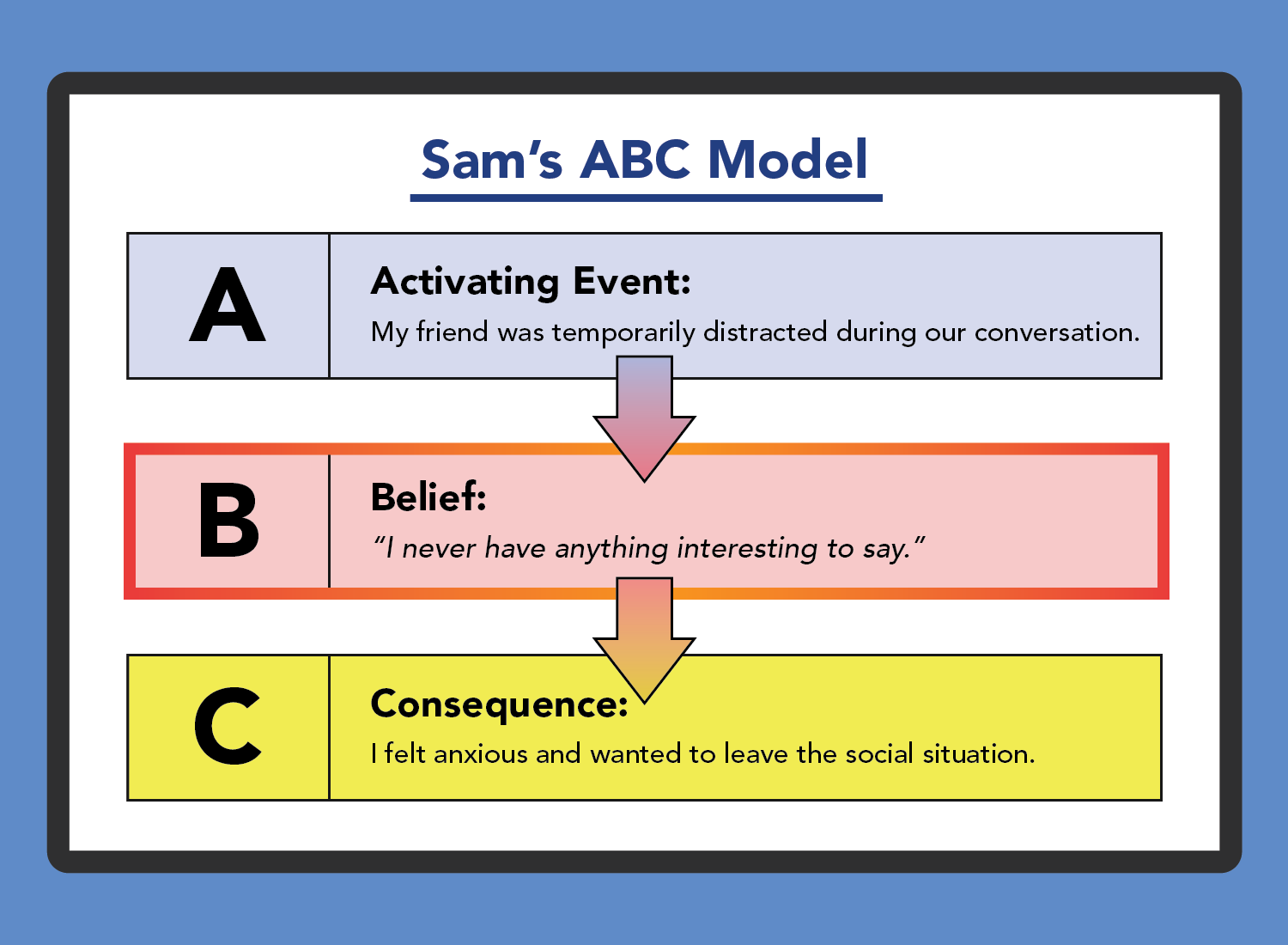

One of the approaches that Beck and his colleague, Albert Ellis, came up with is rational emotive therapy, which is summed up quite nicely by their ABC model:

In Sam’s case, his friend being distracted was the Activating Event, prompting a Belief that he never has anything interesting to say, resulting in the Consequence of dread and an automatic avoidance response. It is this erroneous belief about himself that connects his friend’s temporary distractedness with the resulting feeling of anxiety.

The cognitive therapist would start by working with Sam to identify the false belief that is connecting the activating event with the consequence:

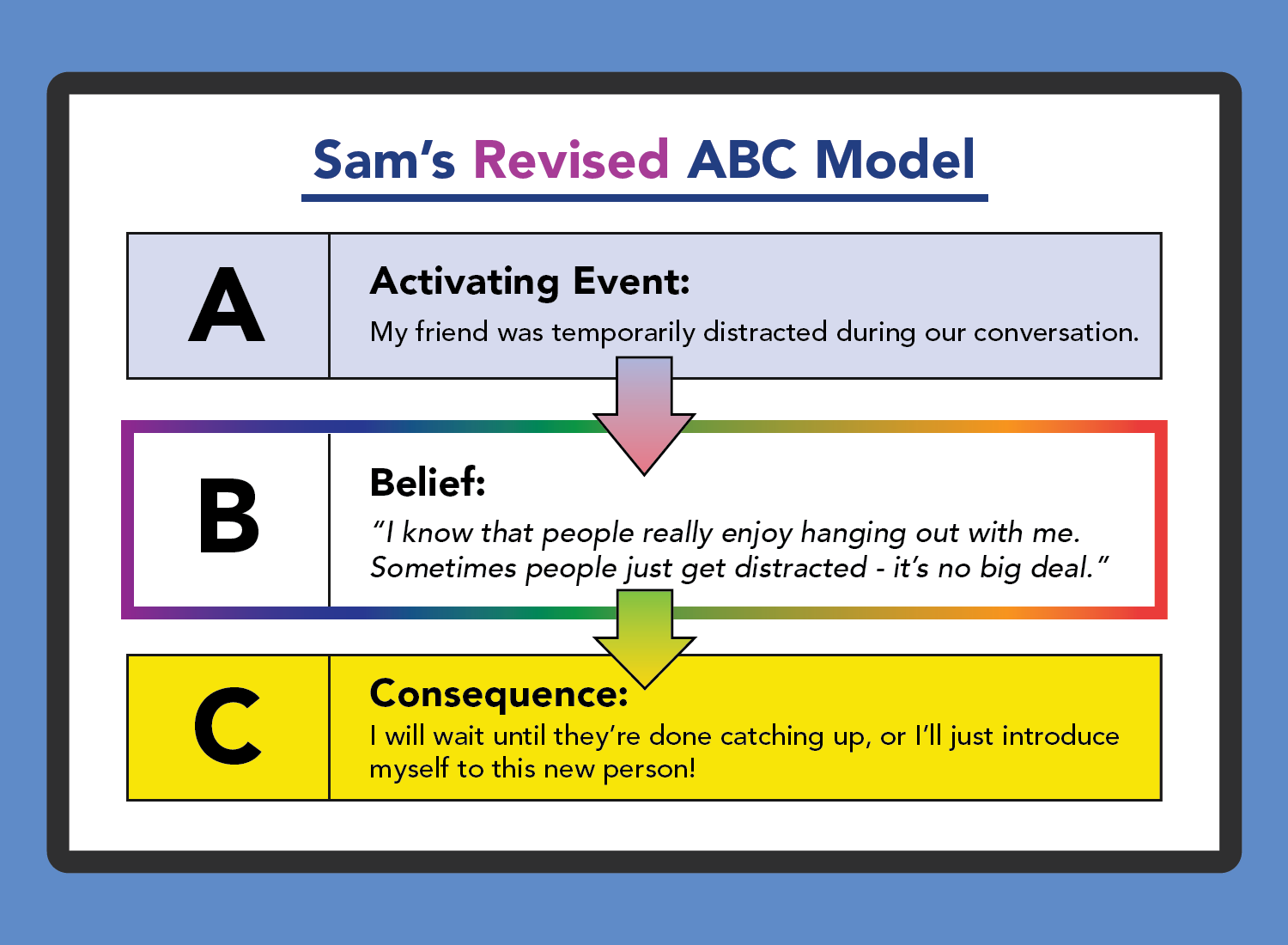

Once it is identified, she will help him correct the cognitive errors underlying that belief, and would then modify that belief with a more realistic one that doesn’t trigger his anxiety.

This modification of his belief allows the link between the activating event and the consequence to break, which will help him see that social situations are nowhere near as threatening as he perceived them to be. By breaking this ABC chain with positive affirmations and alternative beliefs, the behavioral avoidance associated with social stimuli can gradually be weakened and eliminated.

As you can imagine, CBT requires consistent, rigorous communication between the therapist and patient, and its efficacy relies upon the client’s ability to accurately self-report his situation. This is what is known as an explicit form of treatment, in which the client uses his conscious awareness and verbal reporting of emotional experiences to reappraise and change them. The client will have to consciously use working memory to identify false beliefs, replace them, and report these shifts (both to himself and to the therapist) as he’s making them.

Since executive control and conscious processing are the working gears of explicit methods, the area of our brain that is targeted with CBT is that magical sage of ours: the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Therapy uses the power of the prefrontal cortex to exert control over the lower lands, which is a process known as top-down attentional control. The goal is to have the PFC keep the amygdala in check by replacing the memories and beliefs that would typically alarm it, thus preventing the activation of the stress response.

Neuroscientists James Gross and Kevin Ochsner have found that a specific part of the PFC, the lateral prefrontal cortex, is the area that plays a primary role in these types of explicit treatments.

The lateral PFC is essential to working memory and consciousness, and while it doesn’t connect directly with the amygdala, it connects to an area in the back of the Land of the Wise responsible for semantic processing (the process of developing factual context of knowledge).

When a stimulus is reinterpreted from a threat to a non-threat in this area of the brain, it weakens the signal to the amygdala, which decreases the activity there as a result. It is through these indirect connections in the Land of the Wise that explicit therapies like CBT ultimately change the sensitivity of the amygdala to various stimuli.

Most forms of talk therapy fall under this circuitry, and this type of top-down control is essential to lessening the emotion of fear. Joseph LeDoux argues that fear is a conscious emotion arising from nonconscious processes, so CBT is very helpful in addressing one’s conscious interpretation of anxiety.

However, what about the nonconscious processes that act as the origin points of fear and anxiety? Those uncomfortable physiological sensations like chest tension, sweating, flushing, etc. that happen before we are aware of them? Or the bombarding of thoughts that happen automatically once a stranger approaches us?

What can we do to decrease the likelihood of these automatic reactions from arising in the first place?

For that, we will turn to the second form of treatment: exposure therapy.

Exposure Therapy

I remember this one episode of the Maury Show I watched over a decade ago that gave me my first taste of how the media depicted exposure therapy. For those of you unfamiliar with Maury Povich, he’s this cardigan-wearing, khaki-donning gentleman that looks like a wholesome, suburban dad…

… who hosted an unbelievably raunchy, fucked-up talk show that routinely had guests celebrating the news that they were not the fathers of dad-deprived children across America.

Despite the horrific premise of this talk show, it was entertainment heaven for a human being without a fully online frontal cortex (i.e. endless droves of teenagers and college students). I absolutely devoured this show in my younger days, laughing hysterically at the misfortunes of people shattering their lives in front of millions of viewers, all in the name of short-lived infamy.

And about a hundred or so episodes in, I came across one in particular that left quite an indelible impression on my psyche.

One of the segments was about a young woman named Mariah, who had an intense phobia of something that most of us would find quite delightful.

Pickles.

In this segment, young Mariah explains to the show’s producers how much pickles freak her out, clearly disturbed and distressed while discussing the topic. Of course, for a young and unsympathetic 21-year-old man like I once was, this was amazing television, and a riveting topic that had me at the edge of my seat.

After listening to Mariah’s distraught grievances, Maury proceeds to hear exactly 0% of it and makes the following recommendation:

“We wanted to see firsthand the extent of Mariah’s pickle phobia, so we sent her to the Patterson pickle factory, where she would come face-to-face with thousands… and THOUSANDS… of pickles.”

The camera then unashamedly follows her around this huge pickle factory, where young Mariah is hysterically crying, screaming, and running away from factory workers holding trays of pickles, inching closer and closer to her as dramatic music plays in the background.

After a minute of showing this footage, we are back in the studio, with Mariah shaking in her seat, clearly indicating that this type of “therapy” did not work in alleviating her fears. So Maury did what any logical talk show host would do next… surprise her by having his own staff come out with hundreds and hundreds of pickles to CURE HER EVEN HARDER!

As the audience cracks up and jeers at her hysterical reactions, Maury makes his away over to her backstage, essentially scolding her by saying that she needs to get over this shit.

And then, in a rare gesture of compassion, he holds her hand and guides her back to the stage… only to conclude the segment by berating her again:

“Pickles? PICKLES?! … What’s next?!”

When I first watched this in 2006, I thought I just witnessed the greatest thing in television history.

But revisiting it now, I can’t help but to absolutely horrified at this shit.

What one person views as a perfectly normal and delightful thing can be another person’s greatest fear. After all, the dictionary definition of a phobia is one’s “irrational fear of or aversion to something.”

Mariah’s phobia could be the result of many things, whether it’s from trauma related to an event where a pickle was in the periphery, something that happened in her childhood that caused her to erroneously perceive it as threatening, etc. More often than not, a phobia comes from a negative cognitive belief underlying the fear of something rather than the actual thing itself – whether it manifests in the form of a pickle or a social encounter depends on the given person and her specific experience.

The type of “therapy” that Maury was trying is one that is often glorified and portrayed in self-help advice today. It follows this simple formula:

Having trouble with x? Just do y.

Generally, y is a super simple solution that views the problem, x, as a one-dimensional issue that doesn’t take individuality into account. Common examples include:

Having trouble with obesity? Just stop eating too much.

Having trouble with smoking? Just cut back on the habit.

Having trouble with a fear of something? Just face it head-on.

Ironically, the real problem with these statements is not about their comical oversimplicity, but more so in the fact that there is truth embedded in them.

Yes, the most reliable way to overcome obesity is, in fact, to control what you eat.

Yes, the best way to stop smoking is, in fact, to decrease how much you smoke.

Yes, the most effective way to overcome a fear is, in fact, to confront it directly.

Since these statements sound perfectly rational on their surface, it makes sense for us to perceive them to be valid solutions. Willpower is assumed to be an innate trait we all uniformly possess, and it is through the mere exercising of it that our problems will be solved.

But, as we all know, that formula doesn’t work the way we’d like it to, primarily because we are all individual human beings with unique histories, predispositions, biological makeups, upbringings, and general life experiences. The infinite possibilities of human experience are not considered in this one-size-fits-all formula, so what we first need to do is set the intention to enact change, and work diligently to implement the right method that will help us overcome our fears.

There are many forms of exposure therapy that are used on a case-by-case basis (not included is Maury’s technique of doing it in front of a live audience of giggle-happy, non-empathetic strangers), but each one’s goal is the same. Through the client’s repeated exposure to the anxiety-inducing stimulus, he can learn that these situations are, in fact, not dangerous or threatening, and his behavioral responses to them can shift accordingly. Additionally, it can result in a decreased presence of those dreaded automatic physical discomforts as well.

Exposure therapy is often considered to be one of the most effective forms of treatment for anxiety disorders, but how does this work from a neurobiological standpoint? Why does repeated exposure to a stimulus help in controlling and reducing one’s anxiety to it?

To answer this, let’s take a trip back to our high school biology classes, and revisit the work of this wonderful fella:

His name is Ivan Pavlov, and if you don’t remember his name, you’ll likely remember the experiments he’s known for, which involves dogs, food, buzzers, and a lot of saliva.

Pavlov was initially interested in how digestion worked in mammals, and used dogs as the mammalian representative for his research. He wanted to explore why dogs drooled as a response to being fed, so he set out to collect saliva from them by somehow inserting test tubes in their cheeks and measuring that slimy goodness.

While conducting these experiments, Pavlov noticed something interesting. Rather than salivating when the food was placed in front of them, the dogs would salivate whenever they heard the footsteps of his assistant that would bring the food instead. The dogs had learned to associate something neutral like the sound of a man’s footsteps with the excitatory response of salivation that would normally accompany the sight of food.

In other words, the dog had conditioned itself to associate the assistant’s footsteps with being fed, and the saliva flowed accordingly.

Pavlov wanted to test if this conditioning could be intentionally replicated, and conducted a series of experiments that would go on to profoundly impact our understanding of human psychology.

In a typical setting without any conditioning, if you present a dog with food, it salivates. That’s as simple as it gets. This is the way natural selection has constructed the dog, and the way the dog has been hardwired to respond.

For this default setting, the food is known as the unconditioned stimulus (US) that leads to the unconditioned response (UR) of canine salivation. Nothing too noteworthy here.

Now let’s introduce Pavlov into the equation.

Conditioning starts when Pavlov takes a neutral stimulus, or something that would typically generate no biological response, and presents it to the dog at the same time as the US. In Pavlov’s case, he used a buzzer (contrary to popular belief, it was not a bell) that would buzz at the same time the food was presented to the dog. The buzzer itself would typically be meaningless to the dog, but by sounding it whenever the food arrived, Pavlov was turning the buzzer into a conditioned stimulus (CS) that the dog now associated with the food (US).

Conditioning would be completed when Pavlov could ring the buzzer (the CS) without the presence of the food (the US), and reliably produce the dog’s salivary response. The dog has learned to associate the sound of the buzzer with the arrival of food, regardless of whether or not the food actually comes out.

This process is known as classical conditioning (or Pavlovian conditioning if you want to give the dude his credit), and it essentially occurs when a conditioned stimulus (CS) is paired with an unconditioned stimulus (US) to produce an autonomic response. This is often referred to as the CS-US association, and its presence is ubiquitous across all ranges of sentient experience.

In Sam’s case, his anxiety likely manifested through a CS-US association that was conditioned by the emotion of fear. Sometime during the course of his life, his brain formed a series of strong memories linking social encounters with fear and anxiety, and these were embedded deeply into his amygdala and hippocampus.

From a classical conditioning perspective, the process may have looked something like this:

- Prior to any conditioning, Sam’s unconditioned stimulus (US) would be the uncomfortable sensations that give rise to fear and avoidance.8 For example, if a wild coyote started running toward him, his heart rate would kick into high gear, causing him to freak out and run away. This would happen on his default, neurobiological setting.

- At some point in his life, a social encounter, which was previously a neutral stimulus that didn’t cause any problems, was conditioned to be the stimulus (CS) that started eliciting the fear response. This could be the result of a traumatic social experience (i.e. shame and embarrassment during a performance, parents berating him for something he said, etc.) or a series of repeated events that were presented at the same time as these difficult sensations.

- A CS-US association has now been formed, with social encounters acting as the CS, and uncomfortable physiological sensations acting as the US. This CS-US memory is then stored in the amygdala, prompting it to sound the alarm every time a social encounter presents itself. This would then lead to the emotions of fear and anxiety, causing behavioral avoidance as a result.

It’s no surprise that the CS-US association is housed in the amygdala, making it the trigger point for any of these fear responses. The ultimate goal of exposure therapy is to break this CS-US association, which is done through a process called extinction. Extinction happens when repeated exposure to the CS no longer elicits the arrival of the US (this is creatively known as a “CS-no US” memory).

For Pavlov’s dog, extinction would occur if the buzzer (CS) was rung repeatedly without any food (US) showing up. The buzzer no longer indicated the arrival of food, so the old CS-US association is replaced by a “CS-no US” memory. As a result, the dog will stop salivating when the buzzer is rung.

For Sam, extinction would occur if repeated social encounters (CS) no longer produced the uncomfortable sensations (US) that would trigger the fear response. Since talking to someone no longer caused his heart rate to elevate and his face to flush, the emotions of fear and anxiety would have no reason to arise.

While progress for cognitive behavioral therapy is determined by the client’s self-reporting of fear and anxiety, the efficacy of exposure therapy is determined by an actual reduction of physiological and behavioral responses. If Sam’s sweating decreases with each social encounter, that’s progress. If his face doesn’t flush as much as it used to, that’s progress.

Exposure therapy tries to close the door to anxiety by halting the rise of the uncomfortable sensations that start it in the first place. This is known as an implicit form of treatment, where we try to alter the nonconscious, automatic responses that are controlled by our nerve-wracked friend, the amygdala.

By repeatedly exposing Sam to real and imagined social encounters, he can gradually learn that these situations are not dangerous, and the uncomfortable physiological sensations that would usually accompany them will start fading away. With each exposure, the surge of adrenaline and norepinephrine would lessen, and the CS-US link can be successfully broken.

While all this sounds great, what is the neurobiological basis for extinction-based therapies like this? How does the age-old adage of “facing your fears” actually calm down the amygdala and reduce the freak-out capacity of the brain?

To answer this, let’s revisit our map and zoom into the Land of the Wise and the Land of the Emotional.

In a study conducted by Joseph LeDoux and Maria Morgan in the early 1990s, it was discovered that a specific area of the prefrontal cortex was able to directly brake the defensive responses brought forth by the amygdala.

This area is known as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex… or the PFCVM… or since I want to stop using so many fucking acronyms for this post, this castle:

This castle is particularly magical because it has direct access to the amygdala, and wields the immediate power to decrease its sensitivity to threats. This superhighway is the connection that implicit strategies like exposure therapy target, and when control over the amygdala is strong, threat detection is properly regulated and the autonomic stress response does not occur.

Exposure therapy’s primary goal is to lessen the nonconscious responses that give rise to anxiety, which is what makes it so effective. If the physiological sensations that you previously had no control over stopped arising, then the emotions of fear and anxiety lose their texture, and ultimately, their power over you.

With each successful exposure to a threatening stimulus, Sam learns that the stimulus actually isn’t that threatening after all. At that point, the PFCVM creates a “CS-no US” memory from this process:

Then the “CS-no US” memory will then take a ride on the superhighway to the amygdala:

And once it gets to the amygdala, it will find the fearful CS-US association currently living in there, kick it the fuck out, and take its place.

As this is happening, the hippocampus (our record-keeper of the mind) will store and encode the context of this memory, applying it to any future occurrences that hold a similar context. It is through the hippocampus’ involvement that iterative learning occurs, and with enough exposures, gradual extinction can take place.

The deliberate interaction between these three players (the PFCVM, the amygdala, and the hippocampus) is what makes exposure therapy so effective, and has led to its widespread usage in the treatment of anxiety disorders. However, exposure therapy is something that needs to be planned with intention and care, as reckless and unexpected exposures can have the reverse effect on clients. Going through the process with a empathetic and trained therapist is the right way to do it; going through it with a shitty person like Maury in front of a live audience is not.

I won’t delve too deeply into the different types of exposure therapies that exist out there, but here are some quick summaries of the popular ones:

(1) Systemic desensitization: Developed by Joseph Wolpe in the 1950s, this method asks the client to gradually expose himself to imagined threats, with each one being more difficult than the last. The client will rank his various anxiety-inducing situations on a scale from 0 to 100 (from least threatening to the most), imagine being in each of those situations with full lucidity, and use relaxation techniques to bring him back down to the baseline level.

For example, if saying “hello” to a grocery store cashier was a 10 for Sam, he would imagine being in that scenario, let the physiological sensations and fear arise, then calm himself down until he would be back to 0. He would continue doing this for each scenario up the scale until he would reach his most threatening situation (100), which might be something like public speaking. Once he could successfully calm himself back to 0 after imagining the most threatening scenario, he would be ready to move on to the next step: in-vivo exposure, or exposure to real-life events.

(2) Graded retraining: This method follows the same formula as systemic desensitization, but involves in vivo (real-life) exposure to events instead of imagined ones. Exposures would happen along a spectrum, starting with the least threatening and progressively making their way toward the most difficult situations.

Prior to starting in vivo exposure, it’s important for the therapist to prepare Sam by assessing his social skills deficits and provide some training in the skills he’s lacking. For example, the therapist may assess Sam’s looming insecurity over social situations and determine that assertiveness training would be beneficial for him. People with social anxiety disorder tend to be unassertive to avoid staying out of stoplight, but that comes at the cost of their desires, goals, and time. Teaching Sam that his needs are just as warranted as everyone else’s allows him to understand that it’s okay to ask for what he wants; this perspective can help him navigate the increasingly difficult social situations he will find himself in as graded retraining continues.9

(3) Flooding: If the prior two methods started Sam off at a 10 on the 100-point scale, this one would start him off at around an 80. Flooding is the proverbial “learn how to swim by jumping into the deep-end” method of exposure, and is designed to elevate the fear response quickly, have Sam feel it acutely, then use muscle relaxation and breathing techniques to calm the fear levels down. If done successfully, he can learn that even in a highly threatening scenario (whether real or imagined), he is left unharmed as a result of it, and the fear is ultimately an unwarranted and irrational response to the stimulus.

This is essentially what Maury was trying to do with his guest, but in the worst way imaginable. It’s absolutely essential for the client to be prepared with the proper tools and skill sets required to enter a high-anxiety situation, and this will take continuous dialogue with a trusted therapist to do mindfully. Flooding therapy isn’t for everyone, so it’s important to discuss what levels of exposure would be doable on a case-by-case basis before entering any of these scenarios.

There are more types of exposure therapies out there, but LeDoux argues that whichever one you go with, it’s important to conduct the exposures in different settings, at different times of the day, with and without the presence of the therapist. By exposing the client to a wide breadth of situations, the fearful CS-US association can be disconnected across multiple scenarios, increasing the chances of its eventual extinction.

As a form of implicit treatment, exposure therapy is useful in controlling the nonconscious processes underlying anxiety disorders, but explicit forms like cognitive behavioral therapy use conscious memory to correct cognitive errors and false beliefs. I view exposure therapy as the way to close the door to the physiological sensations we don’t actively think into existence, while cognitive behavioral therapy shapes and molds the content of conscious thoughts we have to lessen the behaviors of worry and avoidance.

LeDoux states that both forms of therapy should be used in the treatment of anxiety. If Sam only used an implicit treatment like exposure therapy, his physiological sensations may be significantly reduced, but his cognitive errors and false beliefs would remain uncorrected. This can eventually lead to feelings of worry and avoidance to reemerge, which could revitalize the CS-US association, and bring back all the uncomfortable physical sensations again.

Conversely, if Sam solely used an explicit treatment like cognitive behavioral therapy, he may be able to construct rational beliefs about himself and others, but the emergence of uncomfortable sensations like sweating and flushing can trigger new feelings of fear in him. A lot of the time, anxiety sufferers consciously know that they are being irrational about their beliefs, but their body is telling them otherwise.

A common example is when you’re on a plane, knowing damn well that the odds of you crashing on it are ridiculously low, so you can be certain that you’ll make it to your destination safe and sound. However, when that first bout of rough turbulence hits, your amygdala acts up, and the stress response starts bubbling its way up. You could logically assert that you’ll be fine, yet anxiety can still manifest quite acutely.

The same thing can hold true for anxiety sufferers focusing solely on explicit therapy, so coupling it with nonconscious, implicit treatments helps immensely. Both of these treatments use the power of the prefrontal cortex – the magical sage of our brains – to exert its control over the overreactive amygdala, and when they are used together, they unite as a powerful force that can effectively reduce the texture of anxiety in our bodies and minds.

While therapy is an incredible resource for the treatment of anxiety, sometimes it’s not easily accessible to the general public. Healthcare systems and stigmas around the world still have a long ways to go in the treatment of mental health disorders, so working with a therapist could be fiscally, culturally, and geographically unreachable for many people.

Fortunately, our bodies and minds are equipped with some mechanisms that can help navigate us through anxiety-inducing situations without the usage of formal therapy as well. Let’s briefly touch two of these mechanisms that are inextricably connected with one another.

The Breath and Meditation

The breath keeps us alive – no surprise here. Since it is pre-requisite #1 to our continued existence, the brain takes care of it for us in the Land of the Automatic through a structure known as the medulla.

While the medulla puts our breath on auto-pilot, we possess the remarkable ability to alter its rhythm through the power of the Land of the Wise’s superstar, the prefrontal cortex. When we consciously take a few deep breaths to slow down our rate of respiration, we activate the vagus nerve (a long, cranial nerve connecting the brainstem to the body), turning on the all-important parasympathetic nervous system as a result.

The parasympathetic nervous system decreases our state of arousal by lowering the body’s heart rate, decreasing blood pressure, and increasing blood flow to create balance in our internal organs and stress response systems. It’s the proverbial yin to the yang of the sympathetic nervous system (discussed in Part 1), which is what turns on when we need to prepare for a freak-out moment.

Turning on the parasympathetic nervous system will change physiology immediately, and is a highly effective way to calm the discomforting sensations of anxiety. Learning practices like diaphragmatic breathing, which involve the usage of full inhalations and longer exhalations in a rhythmic manner, can be highly beneficial in managing the waves of emotion accompanying these sensations. In fact, it’s so effective that many psychologists are now advocating the teaching of these practices to children, as it can be an essential tool one can use at all stages of life.

While altering the pattern of the breath helps manage the physiological symptoms of anxiety, focusing on the breath as an object of attention brings awareness to the contents of consciousness, preventing anxiety from spiraling in the first place. This is best personified through the practice of meditation, which is something you’ve likely heard of (if not partaken in) at this point.

What was once seen as a fad has now become a widespread phenomenon. Meditation apps now garner millions of downloads, retreats can be found everywhere in the world, and local “gurus” are opening up studios in gentrified cities across the country.

However, underneath all this cultural scaffolding, there resides an undeniable insight surrounding the contents of one’s mind, and learning about it can assist in the treatment of anxiety. Meditation is a topic that warrants a whole post in itself, but we’re not going to do that here. Instead, I want to summarize how it works in the brain, and how it can be used to decrease the emotions of fear, worry, and anxiety.

First, let’s pull up our map of the brain again and head over to the cortex, or the Land of the Wise.

You see the areas I’ve highlighted in orange? These areas collectively make up what is known as the “default-mode network” (DMN), which consist primarily of the medial prefrontal cortex and the medial parietal cortex.10

The DMN is what is active when you are lost in thought, or when you’re lost in what neuroscientists call “stimulus-independent thought.” Whenever your mind is wandering for no particular reason (scrolling through your social media feeds, daydreaming about a past event, etc.), your default-mode network is active; conversely, when you’re using attention to focus on external goal-oriented tasks, neural activity in the DMN slows down, which helps to induce those beloved experiences of flow states.

Although much of the DMN is located in the Land of the Wise, it’s an area that isn’t very insightful a lot of the time. Studies have shown that a wandering mind is largely an unhappy one, and tends to focus obsessively on thoughts about oneself and his relationship with others. The wandering mind tends to conjure up thoughts about one’s past, one’s social standing in relation to others, reflections about one’s emotional status, visions of an imagined future, and all kinds of shit about the past and future.

To put it simply, the DMN is the neurobiological epicenter for one’s sense of “self.”

When we are absorbed in mindless thought and are not aware of the states of our minds, the DMN is fully active and our sense of self is in full force. While feeling like you have a “self” and a distinct ego can seem comforting, the reality is that much of humanity’s problems come from the belief that we are the conscious authors of our lives. The feelings of anxiety and fear are no exception to this.

Anxiety largely stems from an over-identification with the sense of self. Social anxiety’s roots lie in the erroneous beliefs of how others are perceiving your “self,” and generalized anxiety stems from worries about situations that can impact the well-being of your “self.” It is through the constant belief in one’s distinct selfhood that we can fail to see our lives for what they really are: continuously changing pieces of the present moment.

If you’re scratching your head at this point, it’s totally understandable, as a lot of this stuff can sound pretty esoteric. If this whole “sense of self” section sounds a bit woo-woo to you, I get where you’re coming from, but there have been a number of fMRI imaging studies conducted on experienced meditators that shed some light on this.

Daniel Goleman and Richard Davidson, leading researchers in this area, have found that the default-mode networks of seasoned meditators, many of which subscribe to the practice of “no self,” are substantially quieter than average levels. Additionally, studies have shown that the brains of long-term meditators have increased gray matter thickness, which is believed to protect age-related thinning of the cortex.

LeDoux hypothesizes that meditation practices centered around “no self” prevents external stimuli from even entering working memory, thus isolating any memories about the self from one’s current experience. As a result, the practitioner is completely immersed in the present moment, as the brain is simply unable to take input from the external world.

If experiencing a loss of the self is like finishing a grueling marathon, then the practice of mindfulness can act as that very first step toward the finish line.

Vipassana, or the Pali word for “insight,” is a popular form of mindfulness meditation that comes from the Theravada tradition of Buddhism. Although its roots are in Buddhism, it can be taught in an entirely secular manner, as the practice itself can be easily segmented from any religious ideology.

At its core, mindfulness is simply the state of being aware of the contents of consciousness in a nonjudgmental manner. Whether the felt experience is innately positive or negative, it doesn’t matter; mindfulness is about being aware of it and carefully studying the texture of that particular sensation, thought, or experience. And once it is experienced fully without the distraction of incessant thought, one can be fully immersed in the only moment that matters: the present.

Here’s Sam Harris, in his fantastic book on meditation, Waking Up:

“By practicing mindfulness, one can awaken from the dream of discursive thought and begin to see each arising image, idea, or bit of language vanish without a trace. What remains is consciousness itself, with its attendant sights, sounds, sensations, and thoughts appearing and changing in every moment.”

Mindfulness practice can be invaluable to those suffering from anxiety disorders, as it allows discomforting physiological sensations to simply be observed for what they are: patterns of energy that ultimately have no real meaning. For Sam (our protagonist with social anxiety disorder), he can acutely feel the texture of his heart rate elevating, take a moment to study its character, experience it fully, then proceed to let it go as yet another appearance in consciousness. The elevated heart rate doesn’t have any particular meaning or lesson to convey; it simply arises and falls like everything else.

Through this shift in perception, Sam could fundamentally view his anxiety in a different manner. Whereas it once wholly defined how he viewed himself in relationship to others, it is now just an appearance in the present moment that has no greater meaning about him. This shift can be groundbreaking for Sam.

Harris once again:

“My friend Joseph Goldstein, one of the finest vipassana teachers I know, likens this shift in awareness to the experience of being fully immersed in a film and then suddenly realizing that you are sitting in a theater watching a mere play of light on a wall. Your perception is unchanged, but the spell is broken. Most of us spend every waking moment lost in the movie of our lives. Until we see that an alternative to this enchantment exists, we are entirely at the mercy of appearances.”

How much of our time do we spend as reactive, unconscious actors in this movie of anxiety, instead of zooming out and seeing that this film is merely a collection of sensations and old memories broadcasted on a blank canvas? Why do we allow the feelings of fear and anxiety to mercilessly sway us around, when those feelings themselves carry no ultimate meaning?

These are just some of the questions that can be answered through the lens of mindfulness.

It’s fitting that these questions are here for us to ponder as this post nears its end. While the exact causes of one’s anxiety vary on a case-by-case basis, almost all of them are rooted in the same existential source: the false narrative that we construct about ourselves.

There’s a well-known quote attributed to Seneca that reads, “We often suffer more in imagination than in reality.” Anxiety is the physical and emotional embodiment of that statement, and arises due to an unceremonious union of physiological sensations and erroneous beliefs. Concerns about a misinterpreted past and worries about an imagined future are the kindling for anxiety, and being aware of this can put out the proverbial fire before it even has the chance to start.

Instead of allowing fear and anxiety to define who we are, understanding the neuroscience behind these states removes the self-condemnation that accompanies these emotions, and lets us step back and view them objectively. Just like watching a film is nothing more than viewing a play of light on a wall, feeling anxiety is nothing more than experiencing a pattern of energy emerging from your brain. There is no greater meaning. It is simply the result of neurobiological processes that have been learned by the brain, and the great news is that these processes can be unlearned as well.

The human brain is a highly adaptable blob of wonder, equipped with its own magical sage that can correct the mistaken patterns of its other constituents. With the usage of dedicated treatment regimens, the brain can relearn its relationships with various stimuli and adopt healthier, more realistic thought patterns and behaviors.

As we go on, living our lives in a world full of incessant change, it will be tempting for each successive generation to wonder if theirs is the defining era of fear and anxiety.

Fortunately, the very thing that has created this exponential progress is also equipped with the ability to slow it down. The human brain, the product of a turbulent evolutionary process itself, can be used to amplify a false narrative about one’s anxiety, or it can take a moment to realize that this irrational tale can be rewritten.

We all know what’s possible with this magical thing, so let’s take the time to rewrite this story together.

_______________

_______________

Sources

If you’d like to read more about anxiety disorders, their neurobiological origins, and how to effectively treat them, below are some resources I used and referenced to construct this two-part series.

Books

For a thorough, detailed look into the neurobiological underpinnings of the anxious brain:

Joseph Ledoux – Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety

For a step-by-step look into treatment regimens for panic disorders, generalized anxiety, and social anxiety:

Margaret Wehrenberg and Steven Prinz – The Anxious Brain: The Neurobiological Basis of Anxiety Disorders and How to Effectively Treat Them

For a deeply engaging tour de force on neurobiology and behavioral science:

Robert Sapolsky – Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst

For an informative journey into the crossroads of neuroscience and meditation:

Sam Harris – Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion

Resource Hub for Anxiety Treatment

While researching this topic, I came across the Centre for Clinical Interventions’ online resource hub for social anxiety, which has downloadable worksheets that can be used to guide a client through various treatment regimens (resources for generalized anxiety can also be found there as well). For example, here are guides that walk through the ABC model and graded retraining, two methods that were described in the post.

Articles and Academic Papers

Casey Schwartz – A Neuroscientist Argues That Everybody is Misunderstanding Fear and Anxiety

Alexander J. Shackman – The Integration of Negative Affect, Pain, and Cognitive Control in the Cingulate Cortex

Simon N. Young – How to Increase Serotonin in the Brain Without Drugs

Michael Specter – Drool: Ivan Pavlov’s Real Quest

Saul McLeod – Pavlov’s Dogs

Neuroscientifically Challenged – Knowing Your Brain: Default Mode Network

Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T. Gilbert – A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind

Shmuel Lissek – Elevated Fear Conditioning to Socially Relevant Unconditioned Stimuli in Social Anxiety Disorder

European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EBML) – Neural Connection Keeps Instincts in Check

Gregory S. Burns – Neurobiological Correlates of Social Conformity and Independence During Mental Rotation

Jeffrey Erlich – The Role of the Lateral Amygdala in the Retrieval and Maintenance of Fear-Memories Formed by Repeated Probabilistic Reinforcement

Sara B. Johnson – Adolescent Maturity and the Brain: The Promise and Pitfalls of Neuroscience Research in Adolescent Health Policy

Crash Course Video on Neurotransmitters: The Chemical Mind – Crash Course Psychology #3