How Natural Selection Screwed Us

About two times a week, I swim for an hour straight at a nearby pool:

I’ve done this regularly for about 5 years now, which means I’ve done this workout roughly 520 times or so over the last few years.

Yet every single time I reach the parking lot of the pool to get ready for my workout, this is what I feel:

I feel this every… single… time.

Sometimes it takes a herculean effort to get my ass off the driver’s seat and walk toward the pool.

Other times, it’s not as bad… but reluctance is certainly still an emotion at play here.

In the locker room, I unenthusiastically put on my swimsuit, silently hoping that the entire pool was drained out over the last five minutes in some sort of freak accident of physics. I then hobble over to the pool, slightly annoyed to see that all the water is indeed still there, eagerly awaiting my entry for the 521st time.

But when I finally jump in, the cool of the water touches my skin, and something interesting happens.

Immediately, my body starts making autonomous motions before I have the chance to even think about it. My arms stretch out and delve into the water in a rhythmic manner, creating the strokes necessary to propel me through the manmade reservoir.

My head automatically lifts itself up at all the right moments, providing just the proper amount of breath I need to keep this body going.

As one lap becomes two, and two becomes four, my reluctance to be in the water shifts into a feeling of relief and calm.

And before I know it, the experience of swimming starts feeling tremendously enjoyable, and my mind is absolutely loving the experience of being in the water.

At the end of my workout, I get out of the pool, take a shower, get dressed, and head back home. While on the drive back, this lovely feeling takes a hold of me:

I feel this essentially one-hundred-percent of the time.

Really, there’s never a time after a good workout that I don’t feel great, or a time in which I regretted my decision to do so (except for this one time someone took a dump in the pool, and the consequences of that ended up in my swim lane… it was horrific).

So if this is the case, why do I feel this unnecessary sense of dread every time I initially show up to the pool? If all my past experiences have shown me that working out will reliably produce a favorable result for me (once again… except for that one dookie incident), why don’t I just enter the pool with a content and excited state of mind every single time?

In other words, why is it so damn difficult to align what I should do with what I end up actually doing?

It turns out that this paradox does not apply merely to exercise — this applies to almost everything worthwhile that we as humans embark upon.

For example, we break our diets and eat loads of junk food at midnight, even when we know that it will make us feel terrible shortly after.

We choose Netflix binges over working on our passion projects with our free time, which we end up regretting almost immediately.

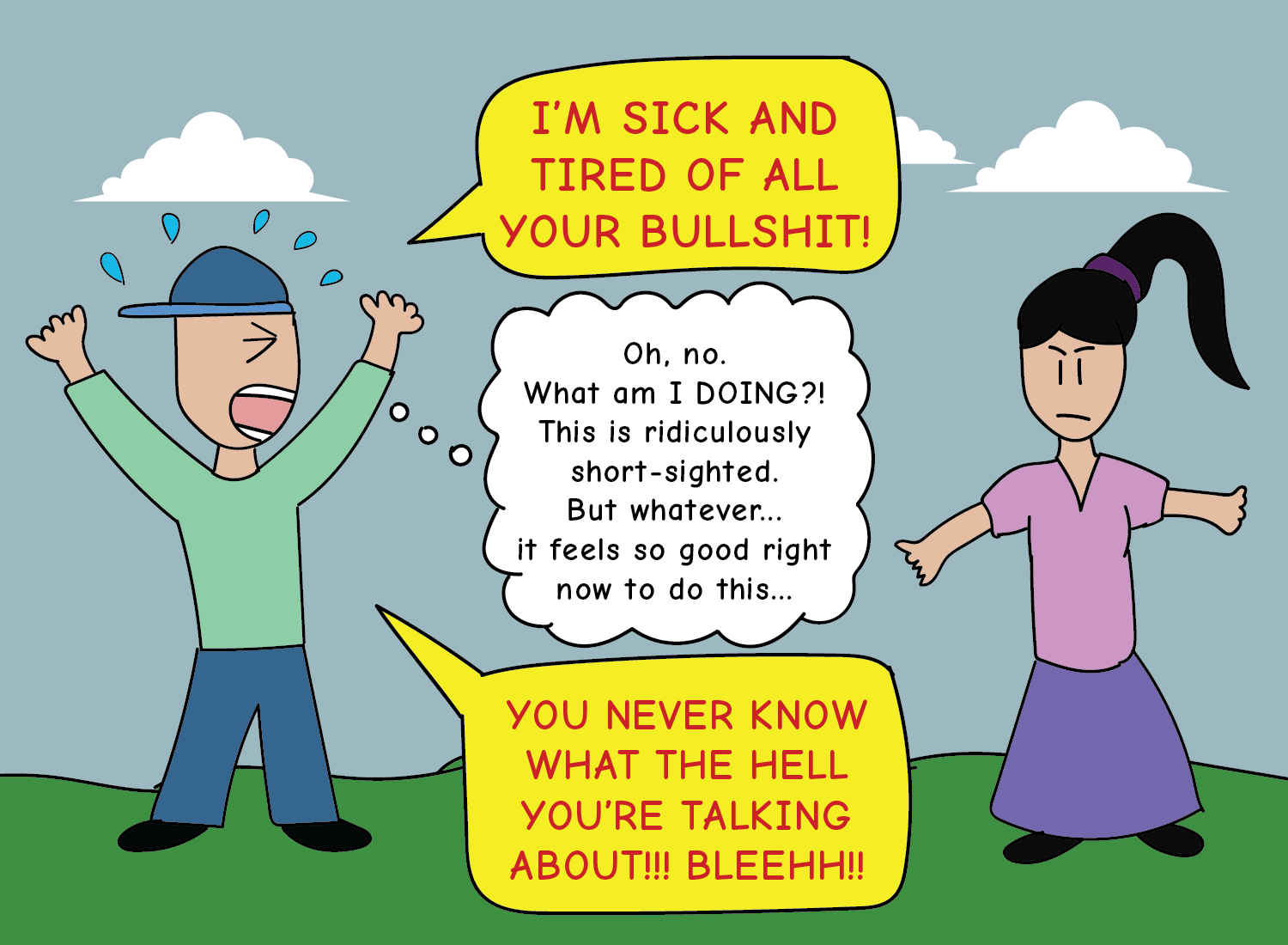

We lose our cool and yell at the people that are closest to us, knowing that we are trading momentary gratification for long-term regret.

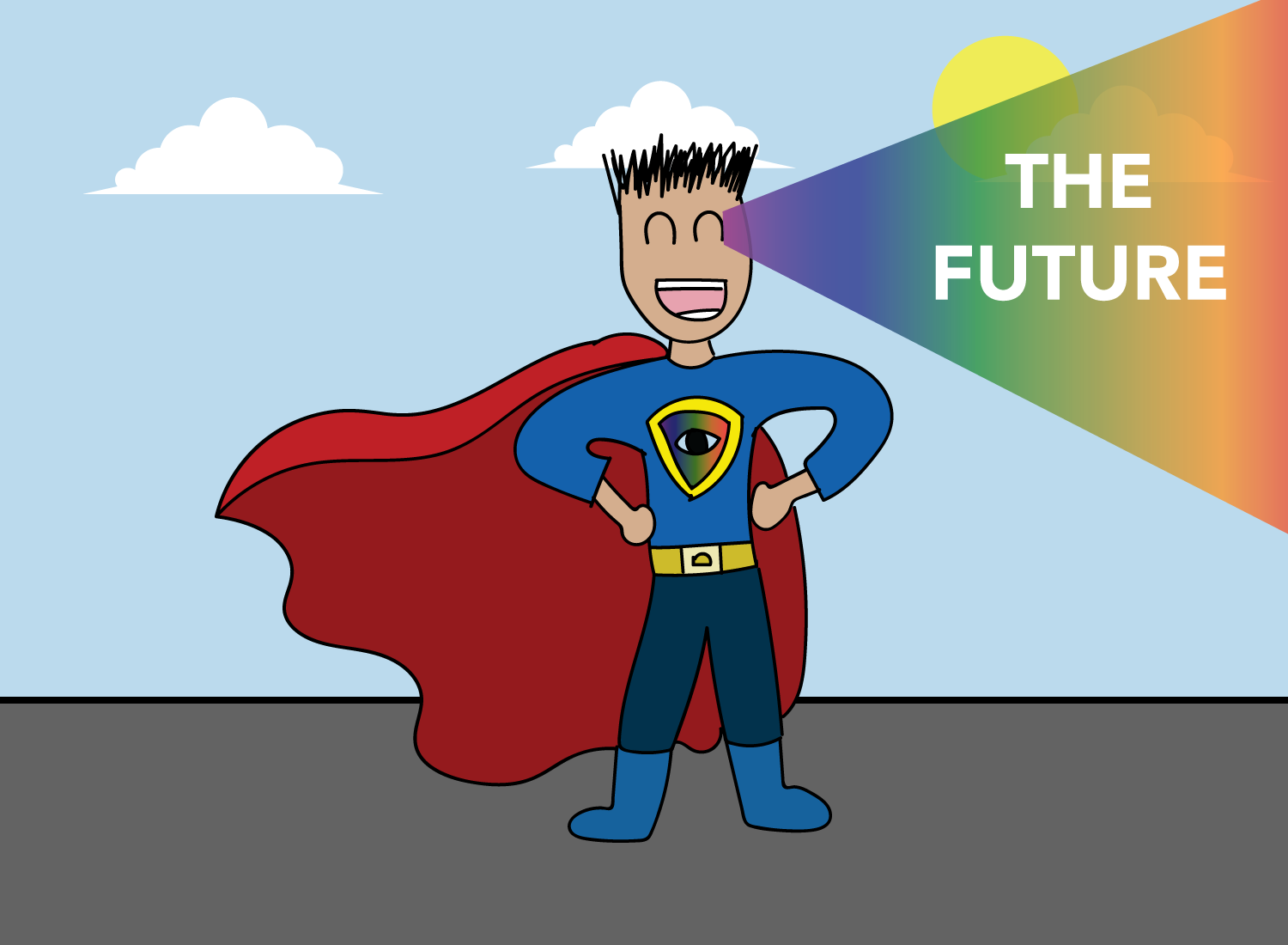

The reason why this paradox is so baffling is because we as humans have been endowed with a superpower that has been designed to protect ourselves against this very behavior.

This superpower has allowed us to thrive and prosper in a way that no other species on this planet has. It has allowed us to create technologies that can broadcast images and videos to anyone in this world instantaneously, create vaccines that have prolonged life expectancy to record highs, and believe stories that have led to the creation of money, nations, and governments that bring order to an otherwise chaotic and disorganized landscape.

It has defined our very place on this planet, and is responsible for everything we have created in the name of humanity.

That very superpower is our ability to envision the future.

We can see what’s around us now, study the tools and resources that are currently available to us, and imagine all the things we could do in the near future with them. We can take a look at something (let’s say, a human teenager), imagine what that thing may eventually become (he will be a college graduate one day), and then create a story about that thing given some other variables (since he loves experimenting with different ideas, he will likely go into entrepreneurship).

Although the present moment is the only thing that truly exists now, we have the ability to direct that moment into the places that we would like it to eventually go. And as far as we know, we’re the only species on Earth that can do this.

This superpower, however, is not reserved solely for the grandiose. While it has the power to fundamentally change society, the reality is that this power is most often used in the context of our own normal, everyday lives.

Whether we are conscious of it or not, we all make hundreds of decisions everyday based on our ability to predict good future outcomes. We decide to go for the healthier option at the restaurant because we know it’s better for us, we exercise at the gym even when we really don’t want to, and we begrudgingly clean the bathroom because we’ll be unhappy when it becomes super disgusting.

Conversely, we also refrain from doing things because we can predict shitty outcomes as well. You don’t take the extra five shots of tequila (even though it may be a lot of fun to do so at the moment) because you know you’ll end up puking your brains out. You don’t have the affair to satisfy your lust (even though your body is telling you to) because you know that doing so will destroy a solid marriage that took years to build.

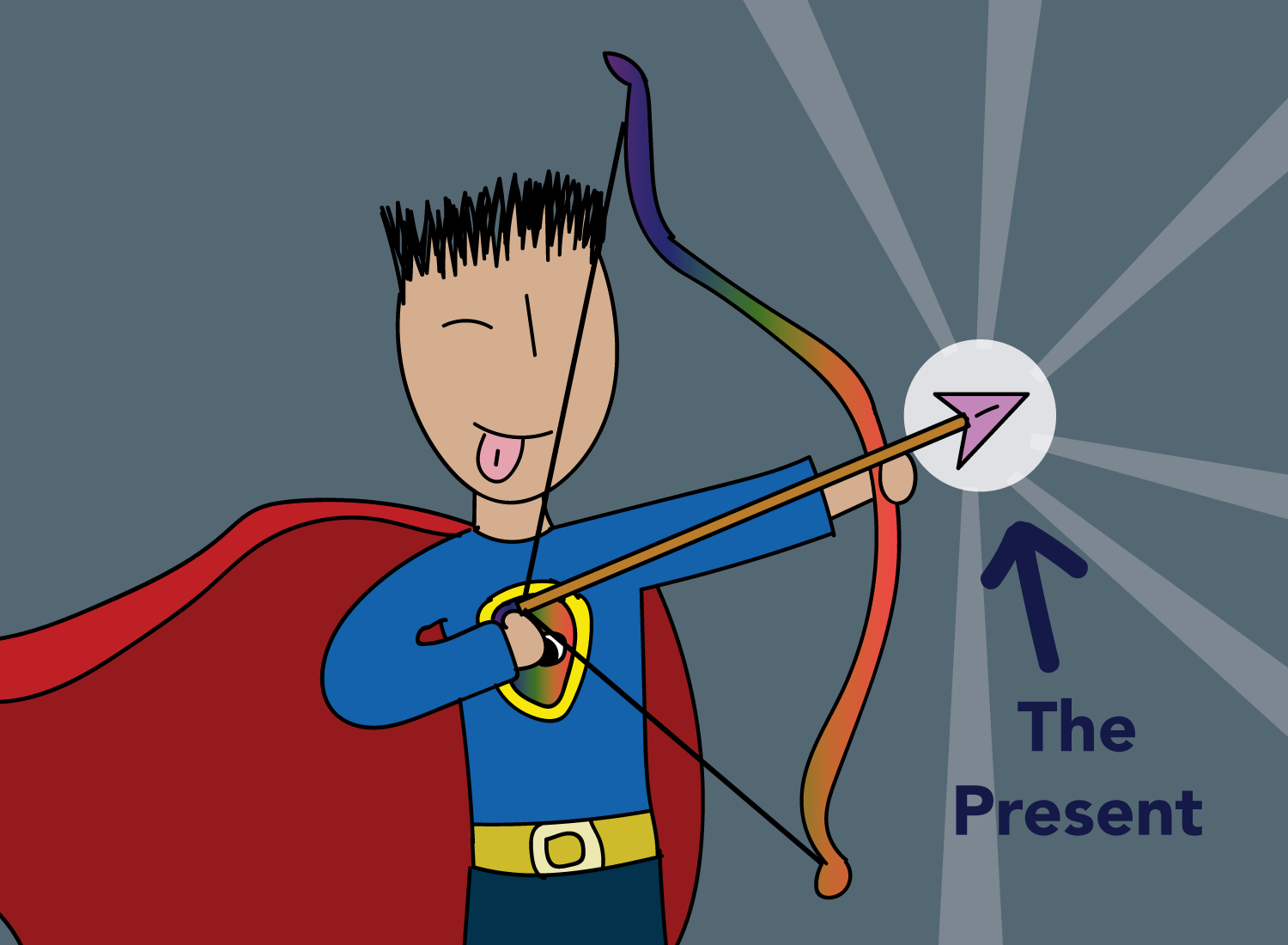

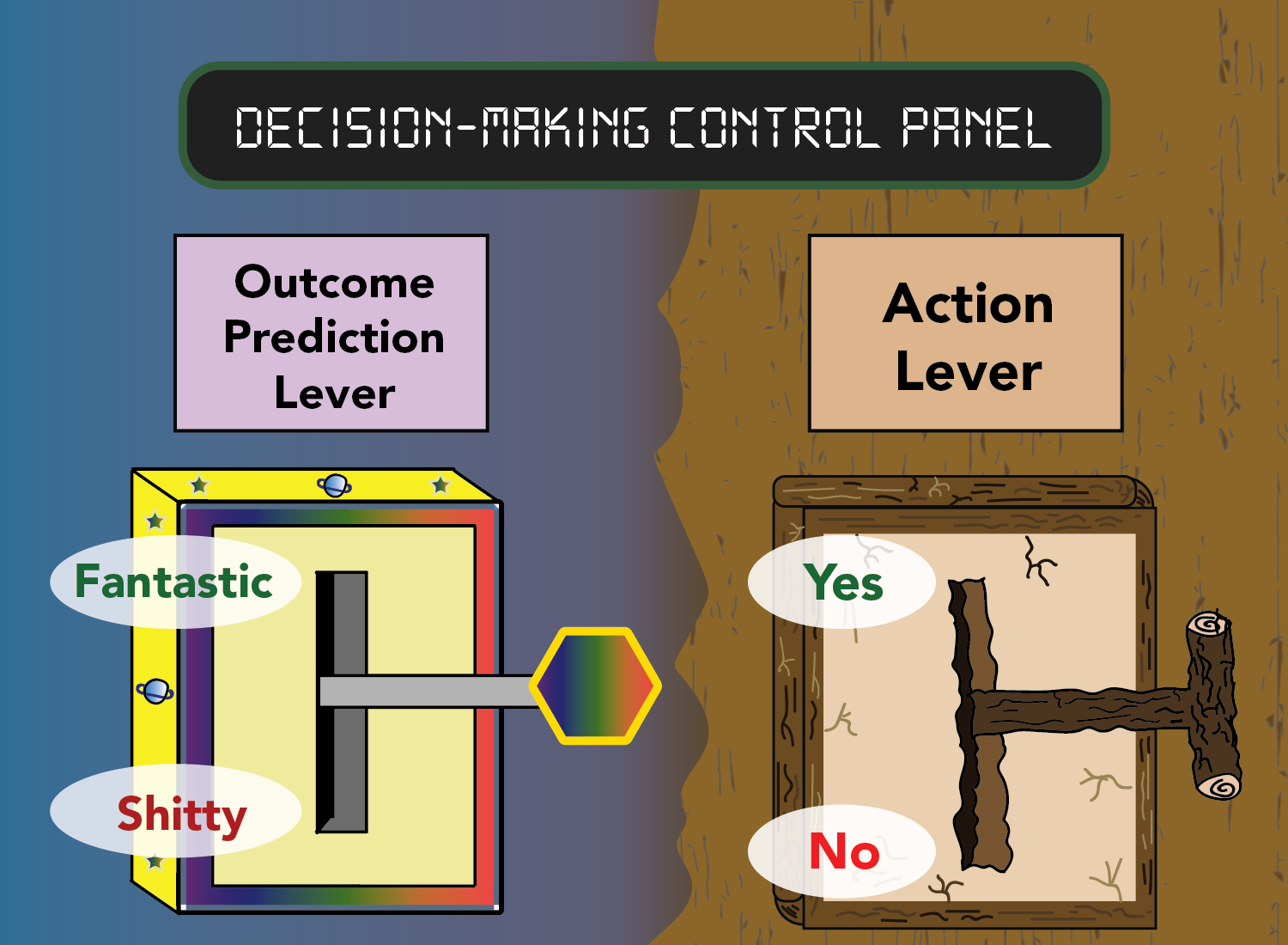

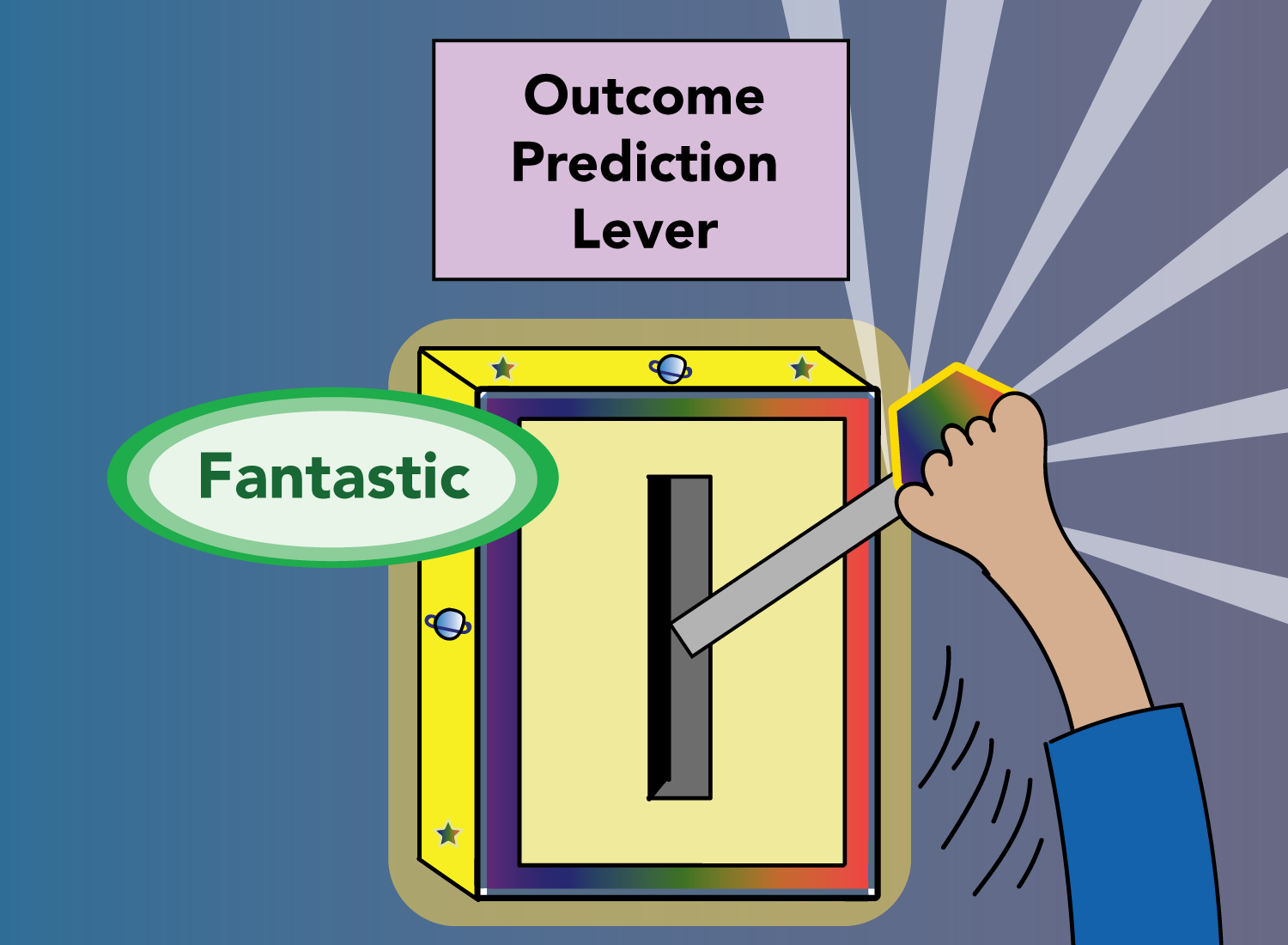

When it comes to our superpower of envisioning the future, I think it can be mapped onto a pretty simple lever that we can pull at any given moment:

When we approach a point in which we have to make a decision (irrespective of its difficulty), we are exercising our ability to pull this lever. There are a lot of factors at play that determine where we will ultimately pull it, but intuition and past experience are good tools to utilize here. Needless to say, your intuition can certainly prove to be wrong (just ask science how close our initial predictions of the Earth’s place in the solar system turned out to be), but when it comes to measuring actions that will have favorable consequences, it is certainly a useful tool to pay attention to.

Additionally, our ability to use past experience as a behavior-modifying tool for future outcomes is also a uniquely human thing, and it is a powerful indicator of knowing what we should do in any given circumstance as well. Past experience allows us to blur the lines between the present moment and the future, as it gives us a good idea of what the present moment will be if it continues to go in a certain direction.

Due to our possession of this superpower, I think it’s rare that we are utterly clueless as to how a specific action will play out. When we hear a friend throw his hands up in despair stating, “Man, this situation sucks. I just don’t know what to do!”, I think what he’s actually saying is, “Man, this situation sucks. I know what I need to do to make it better, but… I just don’t want to do it.”

But since the latter statement doesn’t yield too much sympathy from its listeners, we tend to go with the first one.

Even in the most classic cases of uncertainty, such as getting fired from a job or having an unexpected child, there are distinct actions one can take that will reliably produce a favorable result. Responding to sudden unemployment by diligently applying to jobs or working on an entrepreneurial venture will be good strategies to exercise. Responding to news of your unexpected child by fleeing the country is something that will likely produce a terrible result, so trying to work out the situation with your partner is a much better thing to do.

What may seem like a no-brainer to think is, in many cases, a really hard thing for us to actualize. Whenever we know a certain endeavor will produce favorable results, we often go and do the opposite. While this paradox may seem ridiculous on its surface, its roots are actually quite easy to trace.

Perhaps now is a good time to introduce the second lever of our decision-making capabilities. This one is super simple to use, but the most difficult one to control.

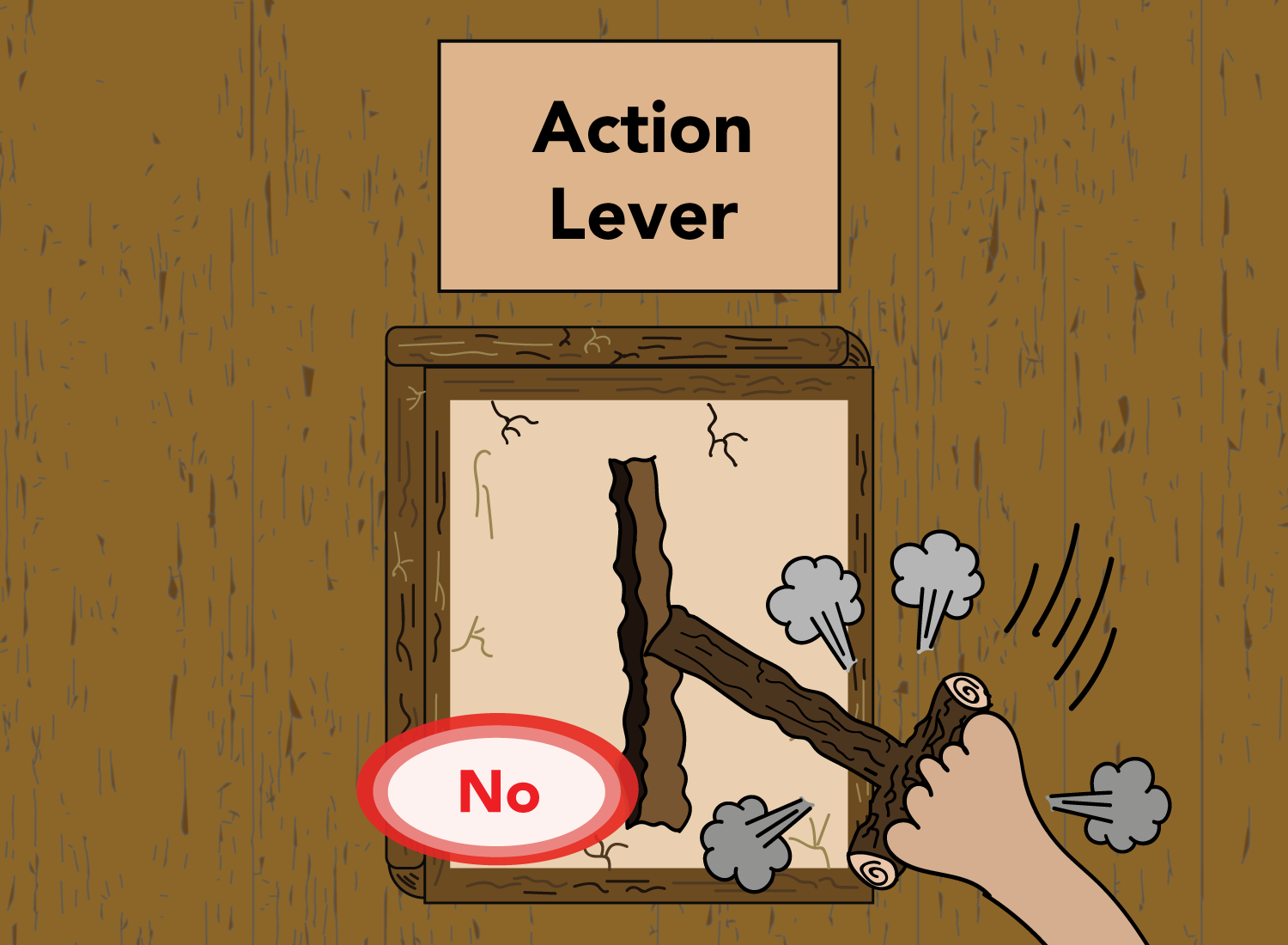

Allow me to introduce the lever of action:

If you’ll notice, this lever looks a little… less sophisticated than the other one. It’s because the lever of action is really, really straightforward, and doesn’t wield any unique superpowers. The only variable here is whether or not you performed the action in question: Did you end up doing your work… or did you not? Did you eat that 2,000-calorie choco-behemoth cake, or did you not?

The action lever simply goes wherever you end up going — there’s nothing too remarkable about it, as even the most basic animals perform the actions they need or want to do. When dogs need to take a dump, they just… go and take a dump. When frogs need to lay eggs, they’ll just chill and lay some eggs. When a flatworm needs to go somewhere… it just… goes there.

The action lever just goes where you ultimately go, but here’s the thing — if there’s no focused intention behind its usage, it will end up going with the result that yields the maximum level of comfort.

And herein lies the core struggle of our existence.

When it comes to our decision-making capabilities, we’re not working with two refined, forward-looking levers of rationality and subsequent action.

No, we’re taking the technologically advanced lever of human imagination + rationality… and combining it with the primal, faulty, and shittily designed lever of human action.

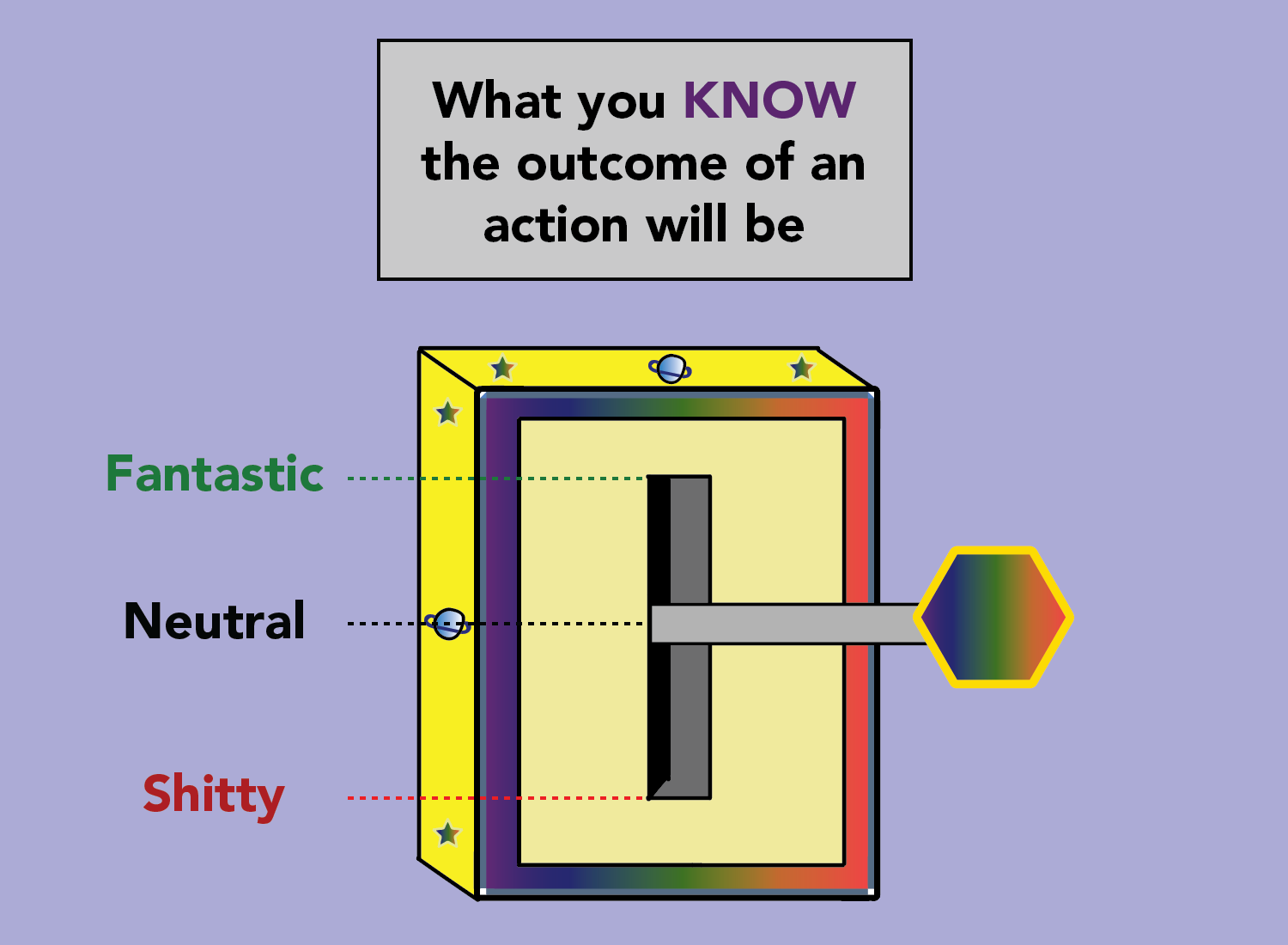

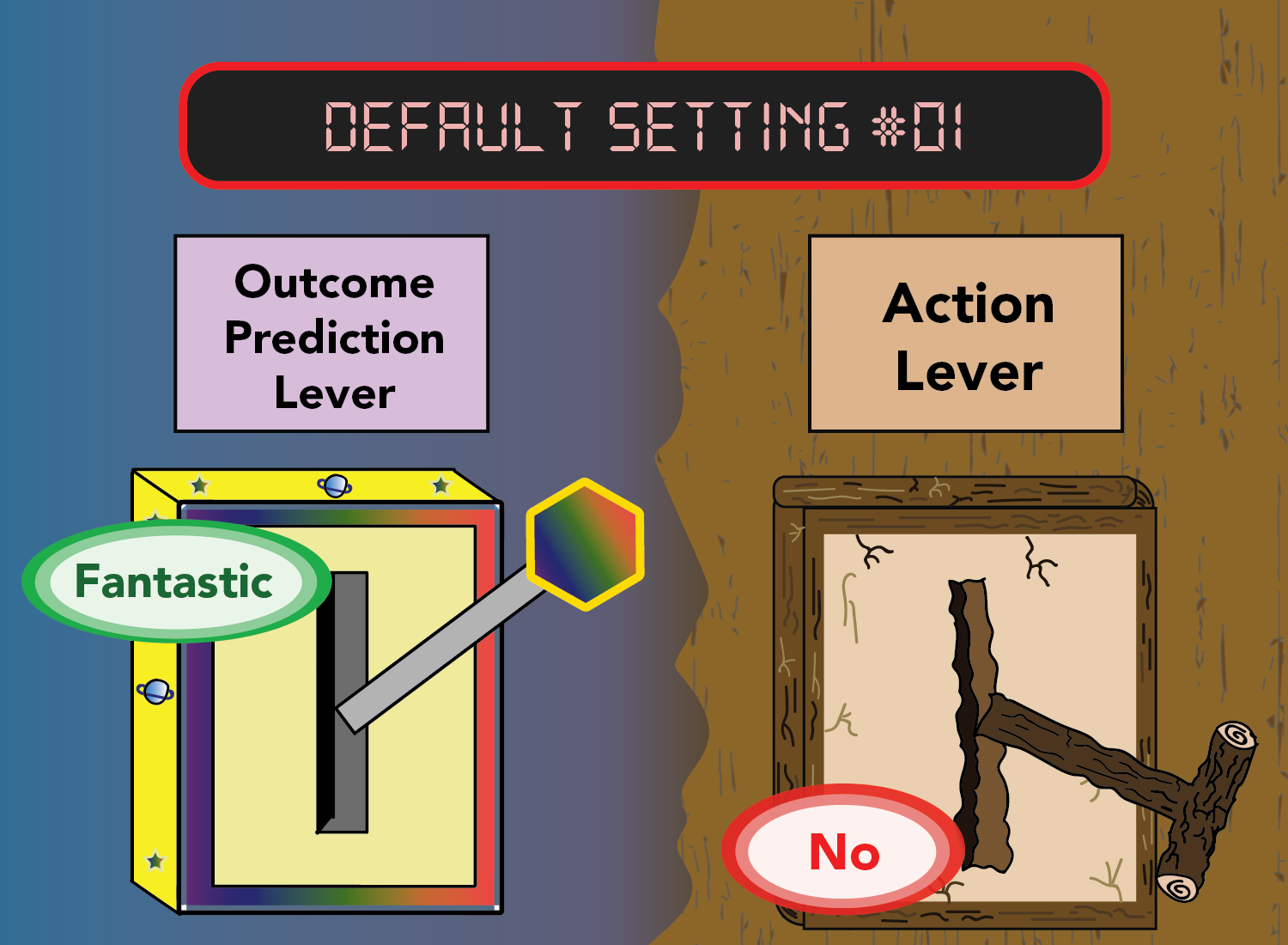

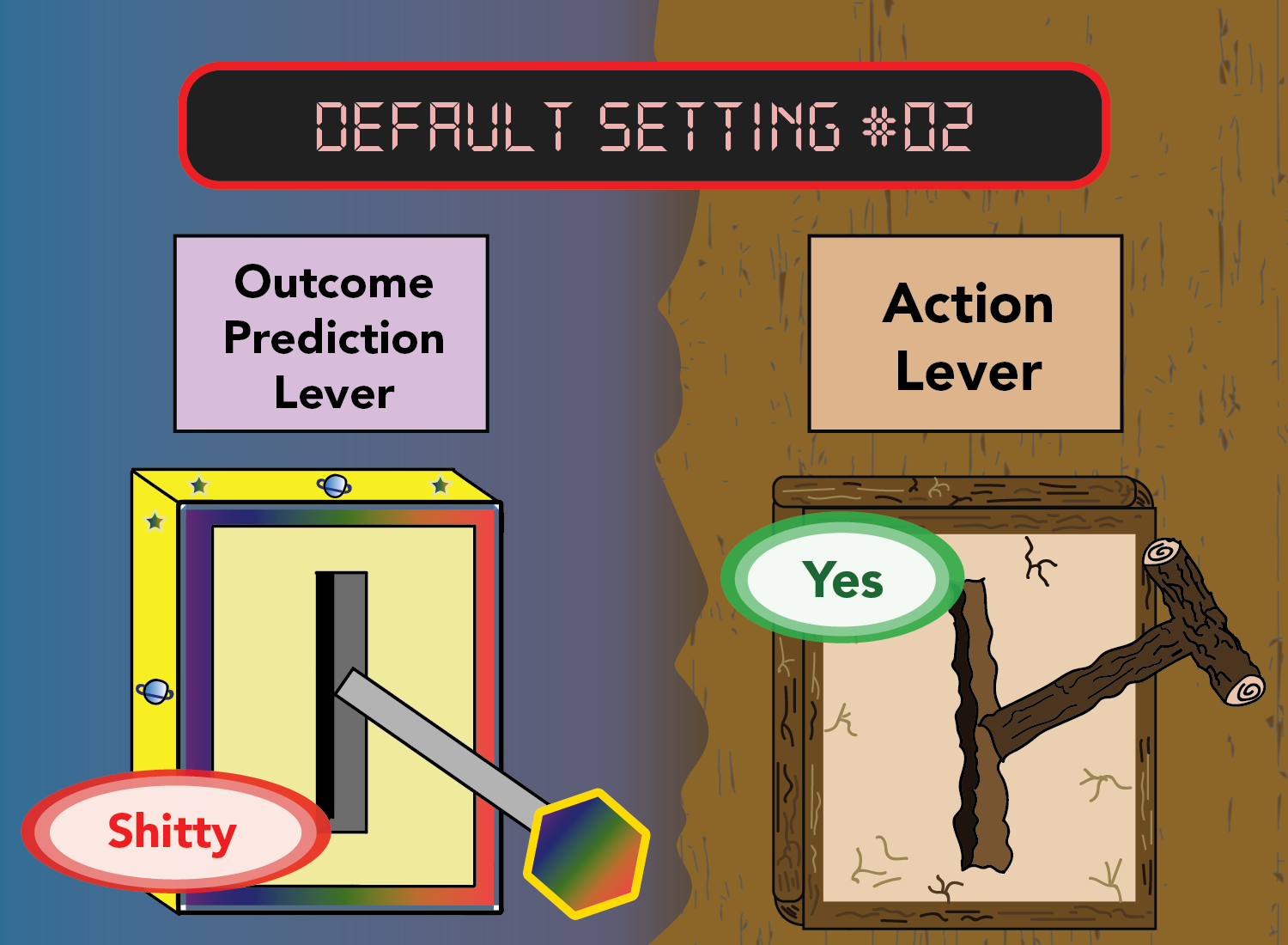

This mismatch in our decision-making process is further exacerbated by the fact that this control panel has a default setting in it that is faulty. It turns out that for anything worthwhile and fruitful, the default positions of what we KNOW an outcome will be and what we want to DO about it are almost always misaligned:

This is illustrated by my earlier example of swimming. I go to the pool because I’m certain that this experience will be beneficial for me — my intuition, research, and past experiences are all aligned in the fact that a nice 1-hour swim will yield fantastic results:

However, when I actually get to the pool, that familiar feeling of dread and reluctance will surface. Excuses of not doing it will circle around, and inaction will be a wonderfully enticing option, for the 521st consecutive time:

This is the default position for almost all things requiring work that will ultimately be worthwhile. To make it worse, the other direction is the default position for all things requiring the tool of restraint — for example, I know that watching a whole season of that new Netflix show will be terrible for my productivity, but if I don’t stop myself, my default action would be to just watch it all anyway:

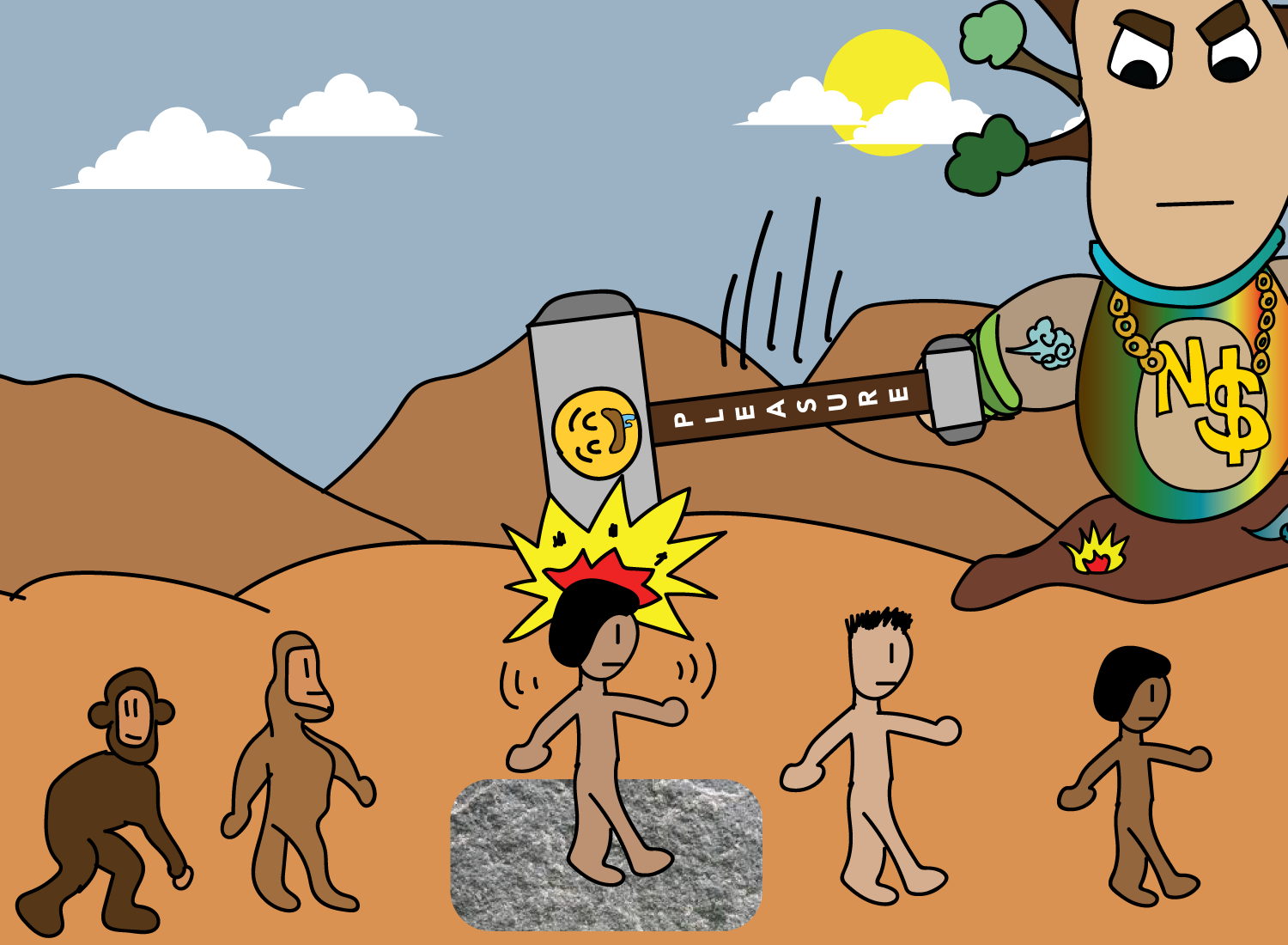

Sadly, this is the situation we often find ourselves in. Without the superpower of rationality, we are mere animals that have evolved over millions of years from single-celled organisms to sponges to jellyfish to amphibians to lizards to rodents to monkeys in a wild ride that has somehow left us in these meat and water bags called the human body. And the driving force of these gradual changes was not some meticulous, detail-oriented genius that shaped our minds and bodies into their ideal formats.

Nope. Instead, we got a rugged, take-no-shit-from-anyone, brute force of nature that has been clobbering away at the clay of life for millions and millions of years.

Say hello to our friend, natural selection.

Natural selection has worked tirelessly over the years to provide us with the hardware we have, and while it’s done a decent job ensuring our survival up until now, it’s fucked up a lot of things along the way too.

The thing about natural selection is that it’s an evolutionary designer using really crude tools to get the job done. Instead of using precise measurements and calculations to ensure the development of a healthy mind, it uses a really blunt instrument to get us to reproduce and pass our genes onto the next generation:

The hammer of pleasure.

I view pleasure as a form of chemotherapy for the mind. While it can be effective in eliminating short-term discomforts, it has the tendency to leave behind so much destruction in the process as well.

Pleasure combats fear and angst (which are two things we don’t want around for sexual reproduction — yet ironically, are two things that have also been built into us via natural selection), but it can also destroy discipline, ethical behavior, and long-term thinking as well. Pleasure can breed ambition and the desire for achievement, but it also makes us impulsive, short-sighted, and ignorant of the consequences our actions can breed. It clouds up the forward-thinking superpower we all have, preventing us from using the tools of rationality, intuition, and intelligence that align our actions with what we know will be good for us.

Natural selection and its tool of pleasure were absolutely necessary for our survival 60,000 years ago, but it’s safe to say that times have changed. For the most part, we don’t have to worry about being abandoned by a small tribe and cast into a void of literal death. We don’t spend much of our waking life hunting for animals, unsure of whether or not our families will be fed that day based on our performance.

In an era where abundance has never been higher, it is becoming more and more important that we place ourselves in scenarios where discomfort is a part of the process. Lethargy may certainly be pleasurable (our ancestors would have loved to just chill and eat all day), but it will ultimately leave you uninspired, complacent, and numb. In an irony that only the universe can devise, the more abundance the world has to offer, the more we wonder what our purpose on this planet is. And as long as our society continues its trajectory toward technological advancement and perpetual connectivity, this need to be productive and purposeful remains at the core of our search for meaning.

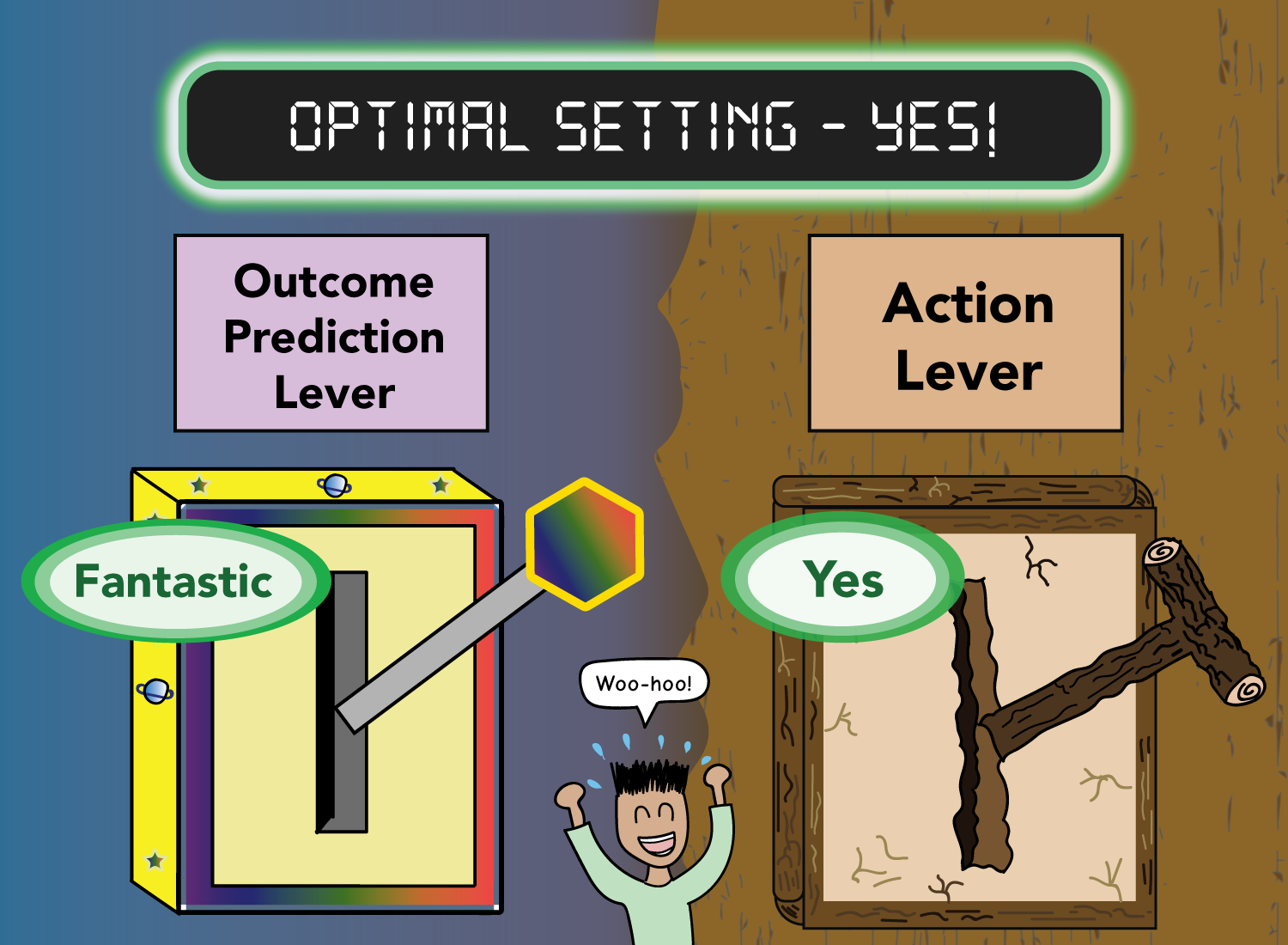

In our default decision-making state, we let natural selection run its algorithm on us — we will value pleasure and comfort over discipline and dedication at any given moment. What we need instead is to let our rationality take over, and allow it to shift the levers of our mind to their symmetrical positions. In other words, we will need to do the tough work of ensuring that what we inherently know is aligned with what we actually do:

Now, if it were as simple as just pulling the action lever to the right place, then we wouldn’t really have any problems in this world, would we? There would be no obesity, no drug addiction, no stealing, no corruption — pretty much every vice imaginable would be wiped out if it were that simple.

So why is it so difficult to move that lever to the right place? Why is it so hard for me to sit down and work on this damn post, knowing full well that it’ll make me happy to do so? Why did I choose to say that thing that would intentionally get my partner angry, knowing full well that it would do me no good?

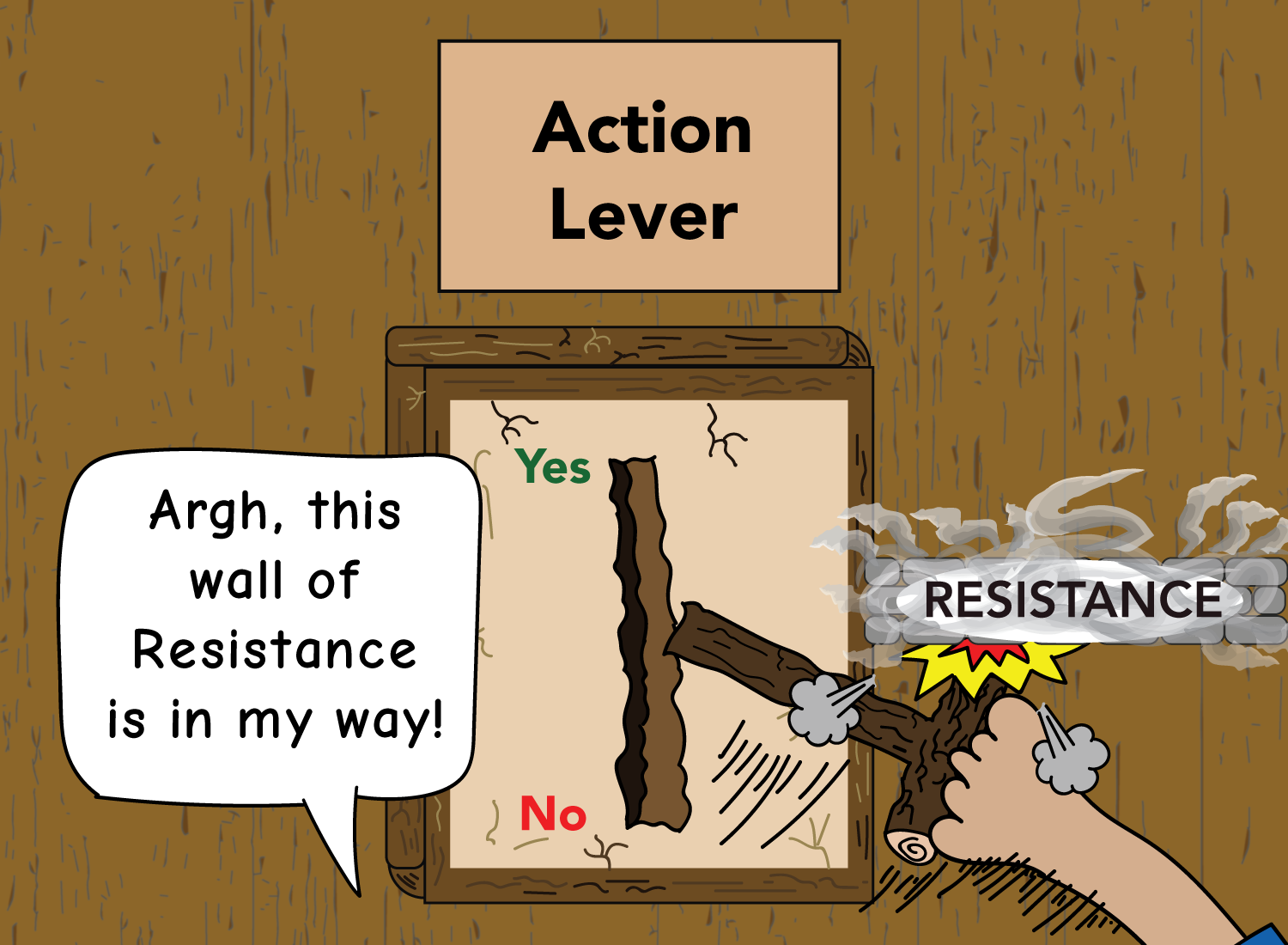

Well, it turns out that our tricky designer, natural selection, has built in some sneaky mechanisms to prevent us from doing anything fruitful. These mechanisms fall under the umbrella of what author Steven Pressfield calls “Resistance,” or a force that rejects long-term growth, health, or integrity in favor of immediate gratification and pleasure. These are the invisible forces that kick in every time we try to align our decision-making levers in the proper place.

Pressfield says that “[m]ost of us have two lives. The life we live, and the unlived life within us. Between the two stands Resistance.”

I think that statement is probably very true, as the Unlived Life is one in which a majority of our decision-making levers are aligned in the same direction, yielding a life of meaning and purpose. Getting there is about winning the battle between our rationality and our biology, so it’s critical to take a look at what these Resistance mechanisms are, how they work, and what it takes to get past them.

I think there are three major adversaries here, and I see them organized into three bad guys in a castle tower that scale in difficulty: Level 1 (Kinda Hard), Level 2 (Hard), Level 3 (Fucking Hard).

I view the journey up this tower as a video game adventure created by natural selection itself. Although our evolutionary designer created this daunting tower and its inhabitants, it also created the mechanisms and tools we require to defeat them as well (after all, our rationality is also one of its products too). A video game creator doesn’t just build the challenges the player must face, it also builds the incremental solutions that are required to beat each stage of the game as well. And as players of this game, our role is to discover the existence of these solutions, and figure out how they can be used to win.

So… who are the mysterious inhabitants living in each of these levels, what motivates them, and how can we overcome them? Well, let’s press pause on our metaphorical video game controllers for now, stand up for a moment, and stretch out our arms, legs, and brains. This game goes pretty deep, so we’re not going to start it here — that’s the job of the next post.

But until then, let’s take some time to reflect on the decisions we make on a daily basis. Which ones are made when our two decision-making levers are aligned? Which ones are made when they are not? Which decisions are made using our superpower of rationality and intelligence, and which ones are made when we’re being impulsive and short-sighted?

When we are mindful of these questions and the misalignments in our decision-making levers, some of the haze that surrounds our everyday actions can be cleared. And it is in this state of clarity where we can look natural selection in the face, thank it for bringing us into existence, but declare that we’re now ready to clean up some of the mess it’s created in the process.

This very journey starts with a single step toward Level 1, and I hope I’ve convinced you to take that step with me.

See you in the castle tower, where the next post will begin.

_______________