From Ignorance to Wisdom: A Framework for Knowledge

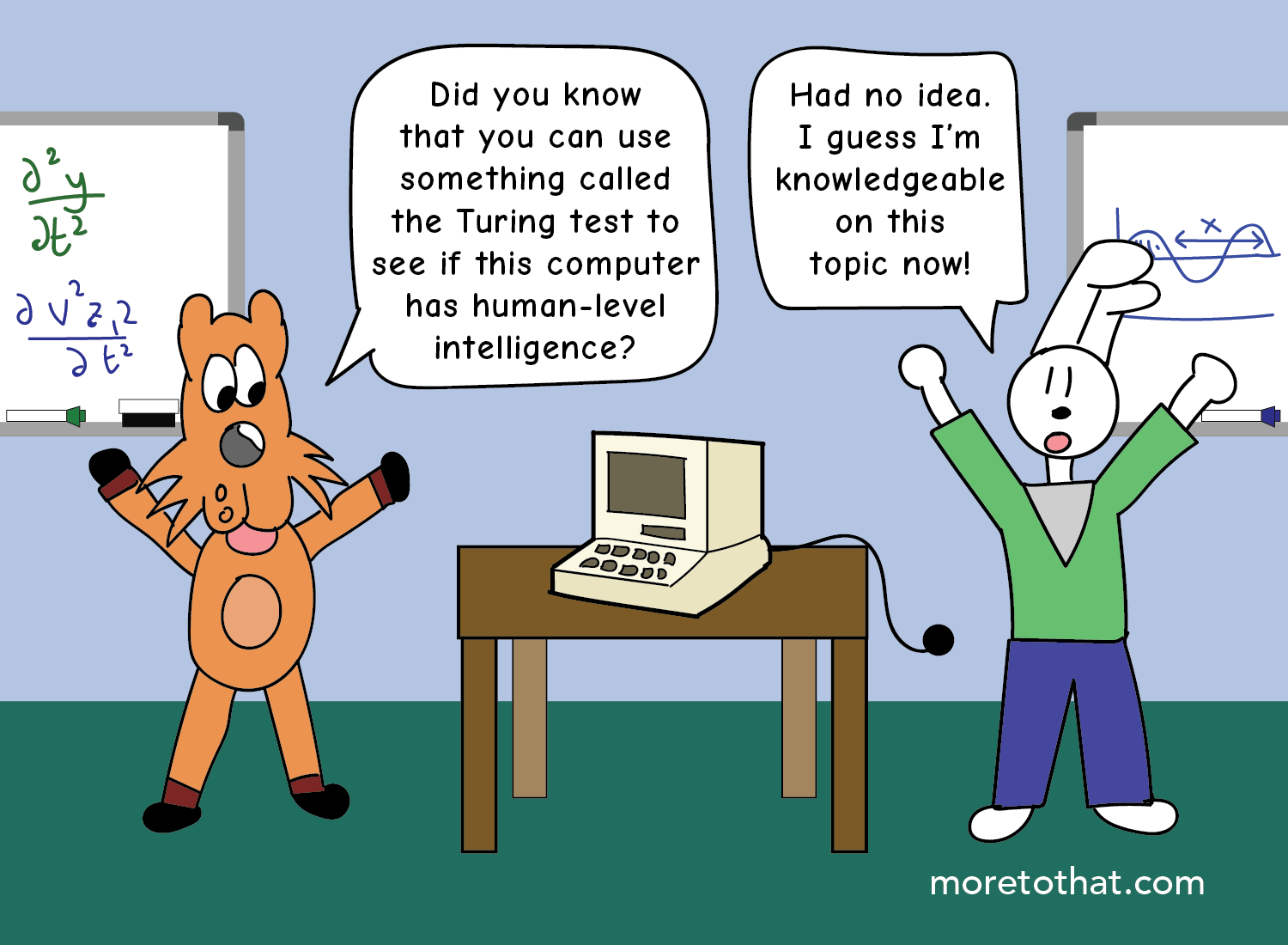

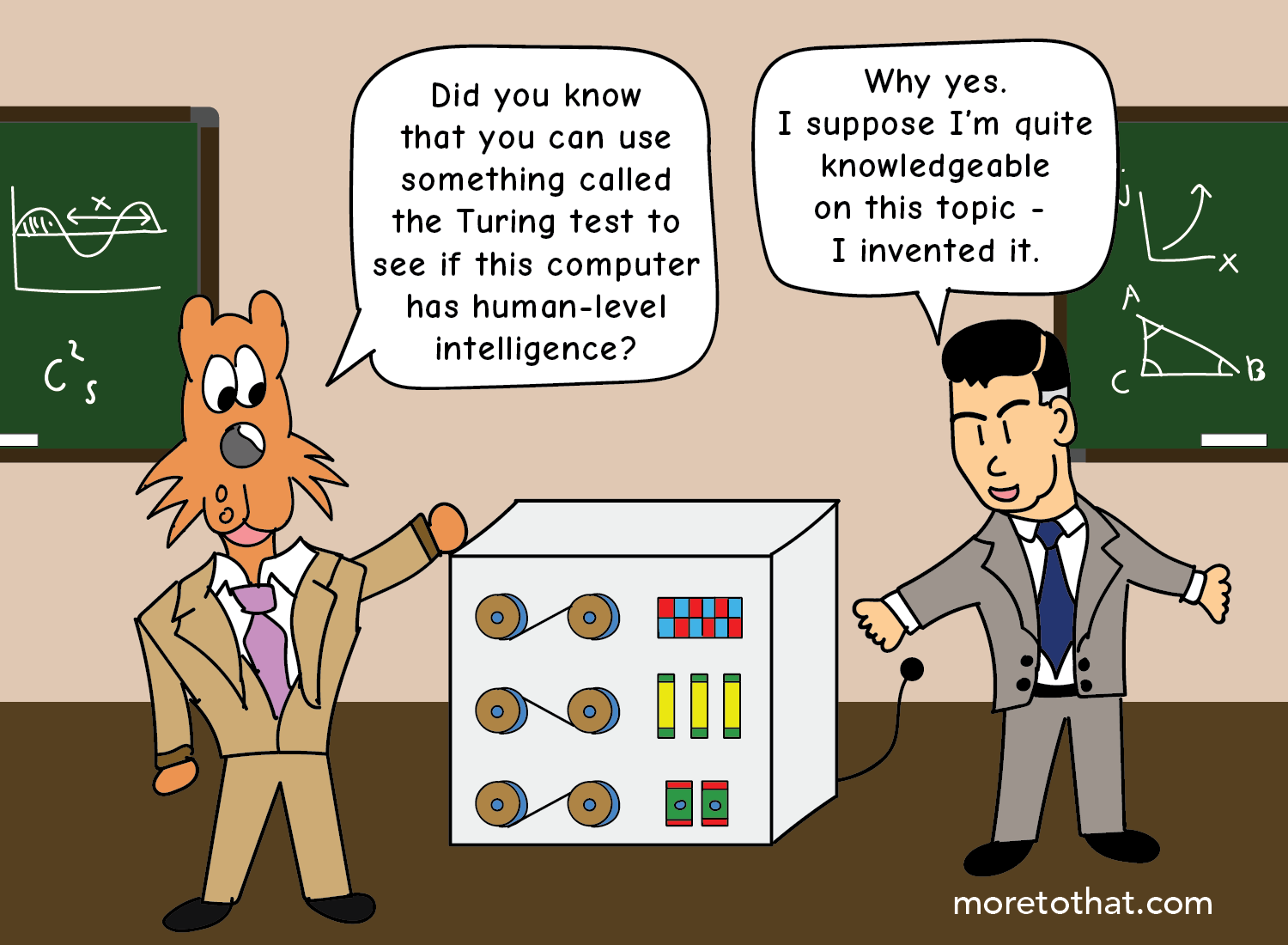

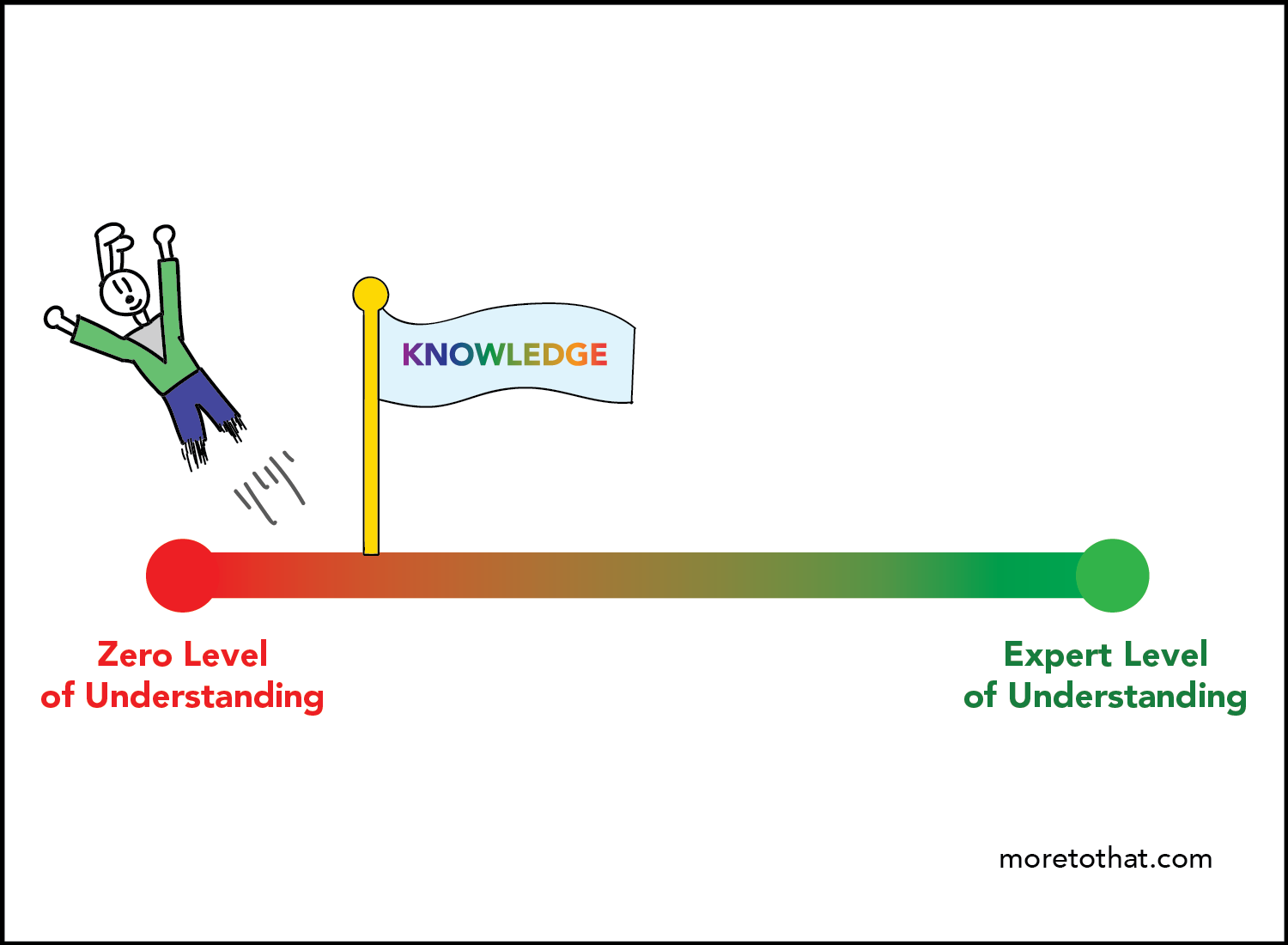

If you learn something for the first time, does that make you knowledgeable?

Or do you have to be an expert in that domain?

Or perhaps it’s somewhere near the middle?

This is the issue with treating knowledge as a concrete thing — a noun. It implies that there is a specific point in which what you know becomes an absolute truth, and that barometer can continuously shift depending on who you are talking to.

To remedy this problem, we need to be able to measure the quality of information we possess, as knowing more about a subject doesn’t necessarily mean that you are right. For example, in our current political landscape, people can be absolutely certain that they are knowledgeable about a particular topic, when in reality they are adopting a position based off intellectually shoddy sources (i.e. consuming news from just one source, having conversations only with people they agree with, etc.).

So in order to measure the quality of how we obtain a piece of information, we introduced the concept of attentional capital in a prior post.

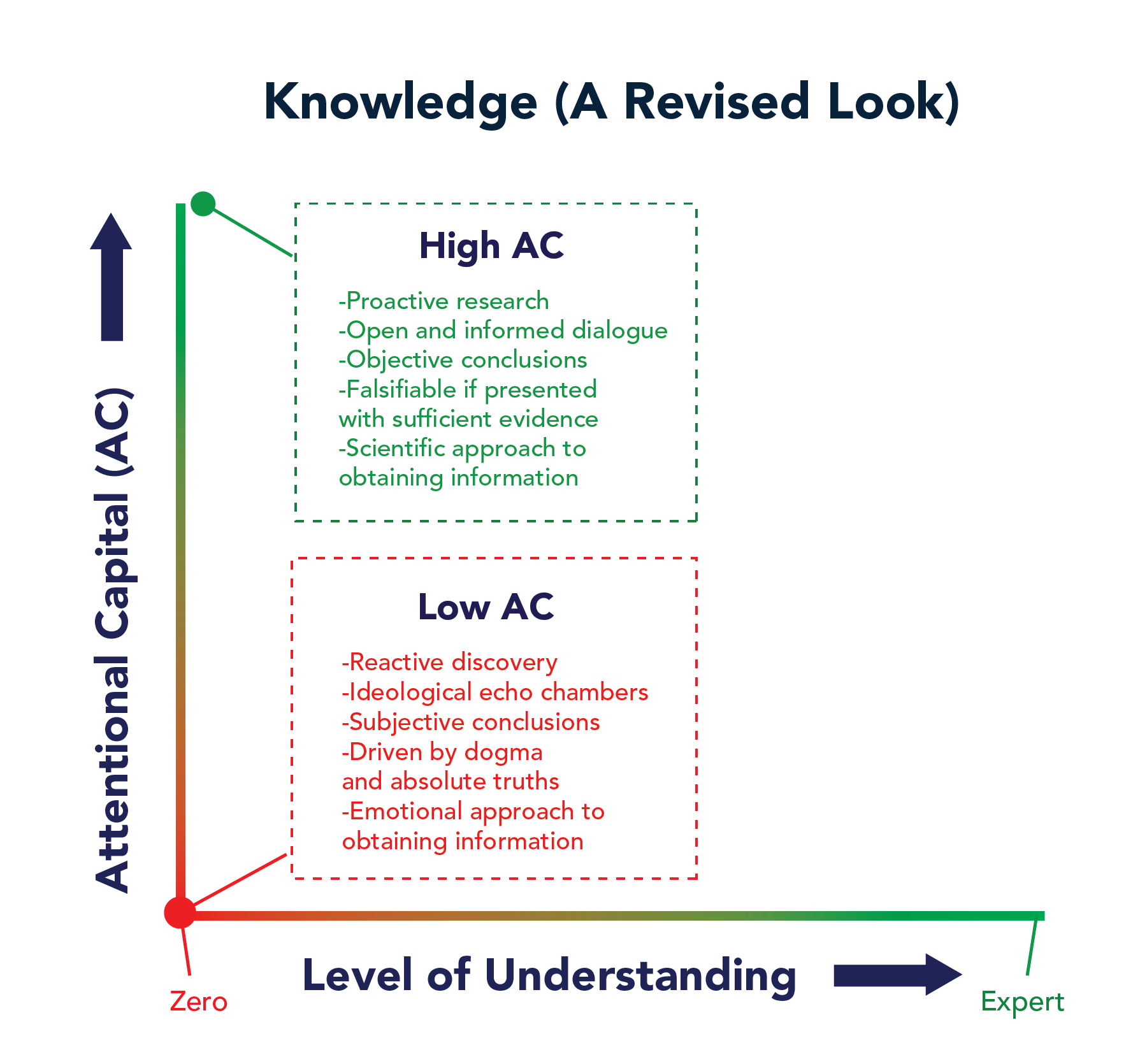

Having a high AC means that you have obtained your information through focused and objective research, tested your findings with other individuals, and would be open to changing your position if presented with sufficient evidence to do so.

Having a low AC means that you reactively believe whatever comes across your news feed, refuse to dialogue with others about your beliefs, and hold onto your beliefs in a dogmatic and tribal manner.

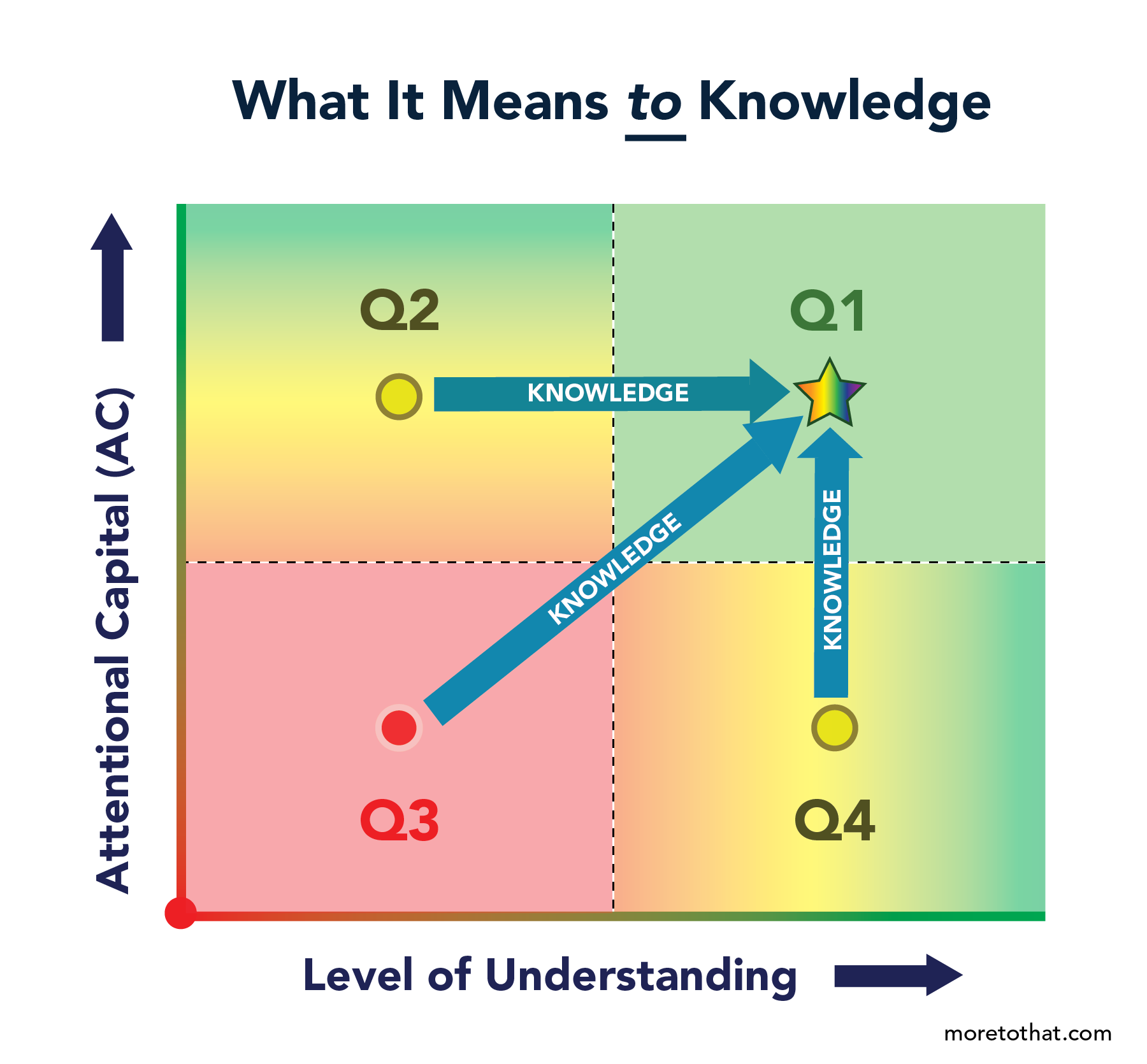

If our level of understanding of a topic is one horizontal line (going from zero to expert), then attentional capital is the perpendicular axis that measures the quality of the information we hold:

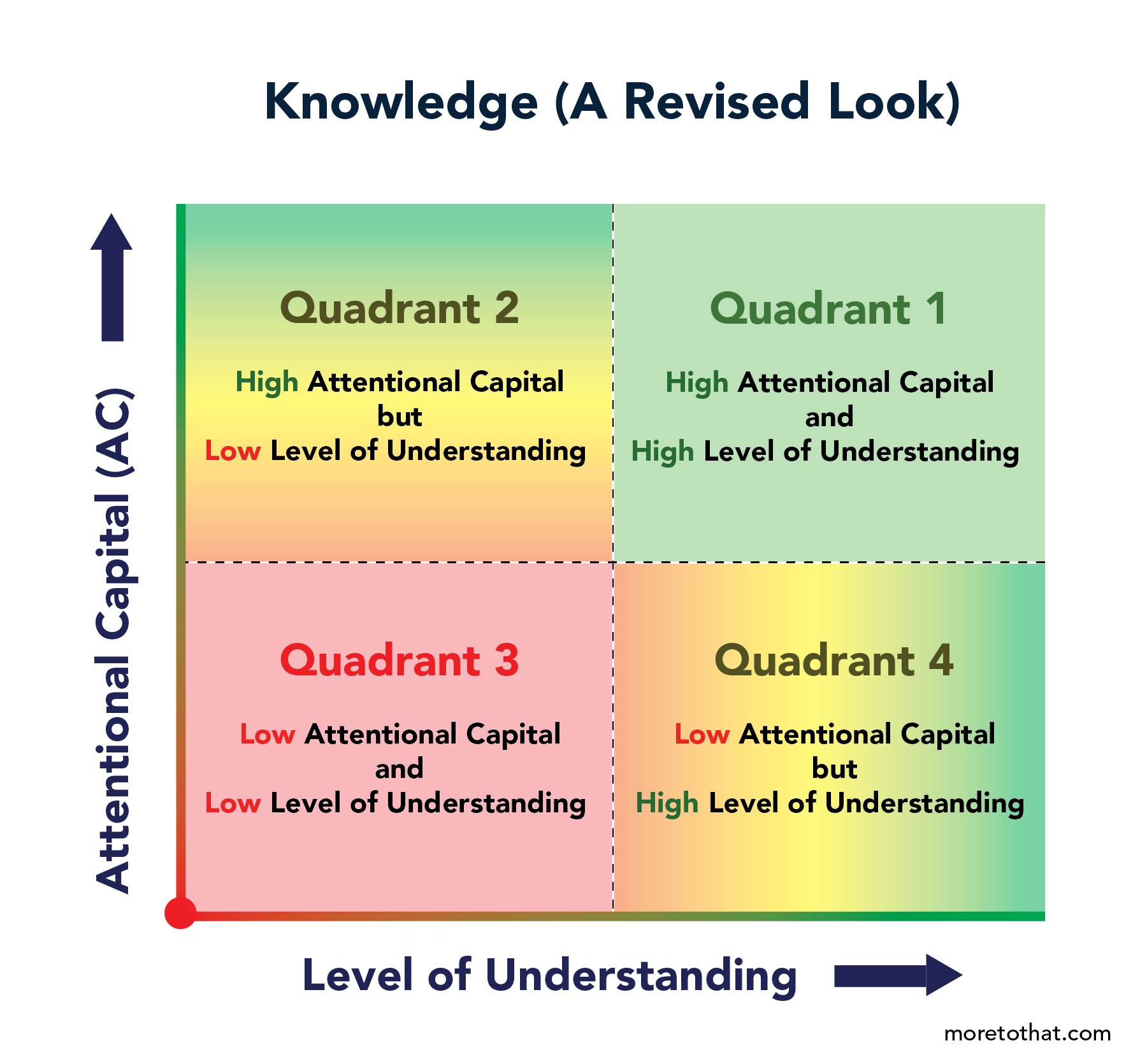

So using this revised look, where does “knowledge” itself reside? To further map it out, let’s divide it into four distinct quadrants:

*Note: While it’s not required to understand this post, I provide a detailed breakdown of what each of these quadrants mean in a previous piece titled “Knowledge Is Not a Thing”.

The goal here is to get to a point in which Quadrant 1 is the home for many of our perspectives on life. In this quadrant, not only do we have a solid understanding of what we know (high level of understanding), but we have also built a really strong foundation on which that information was built upon (high attentional capital).

However, just because you reached Quadrant 1 in something doesn’t mean that you will permanently reside there. We are always in a state of learning and reevaluation, so you can find yourself in any of the other three quadrants at any given moment.

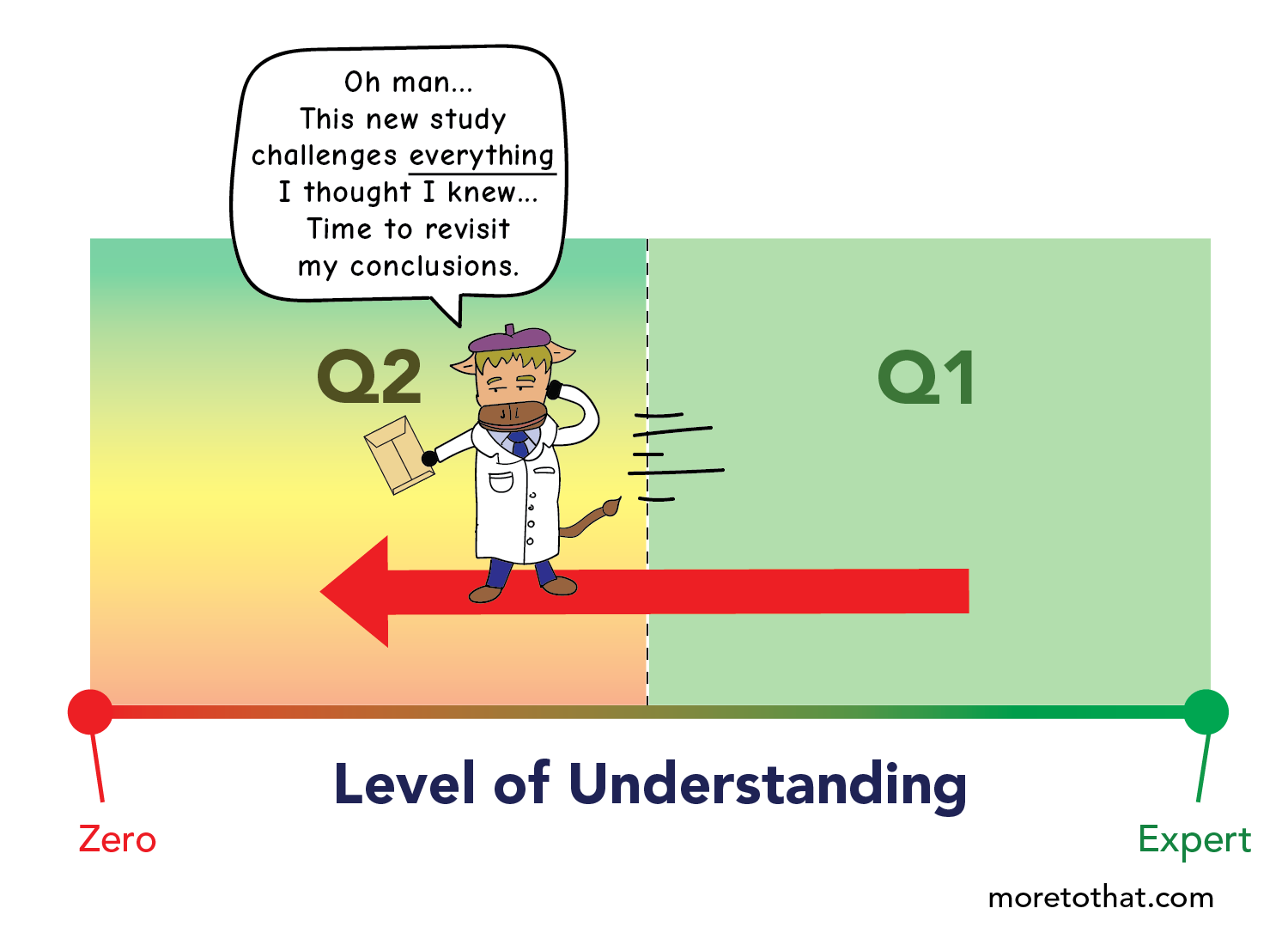

For example, if an intellectually honest scientist is presented with strong evidence contradicting everything he has known, he will find himself in Quadrant 2. This is where his attentional capital is high (as he is still committed to diligently discovering the truth), but his level of understanding has decreased dramatically (since all of his prior conclusions have been disproven).

Unfortunately, not all people are willing to accept that their worldview may have been misled.

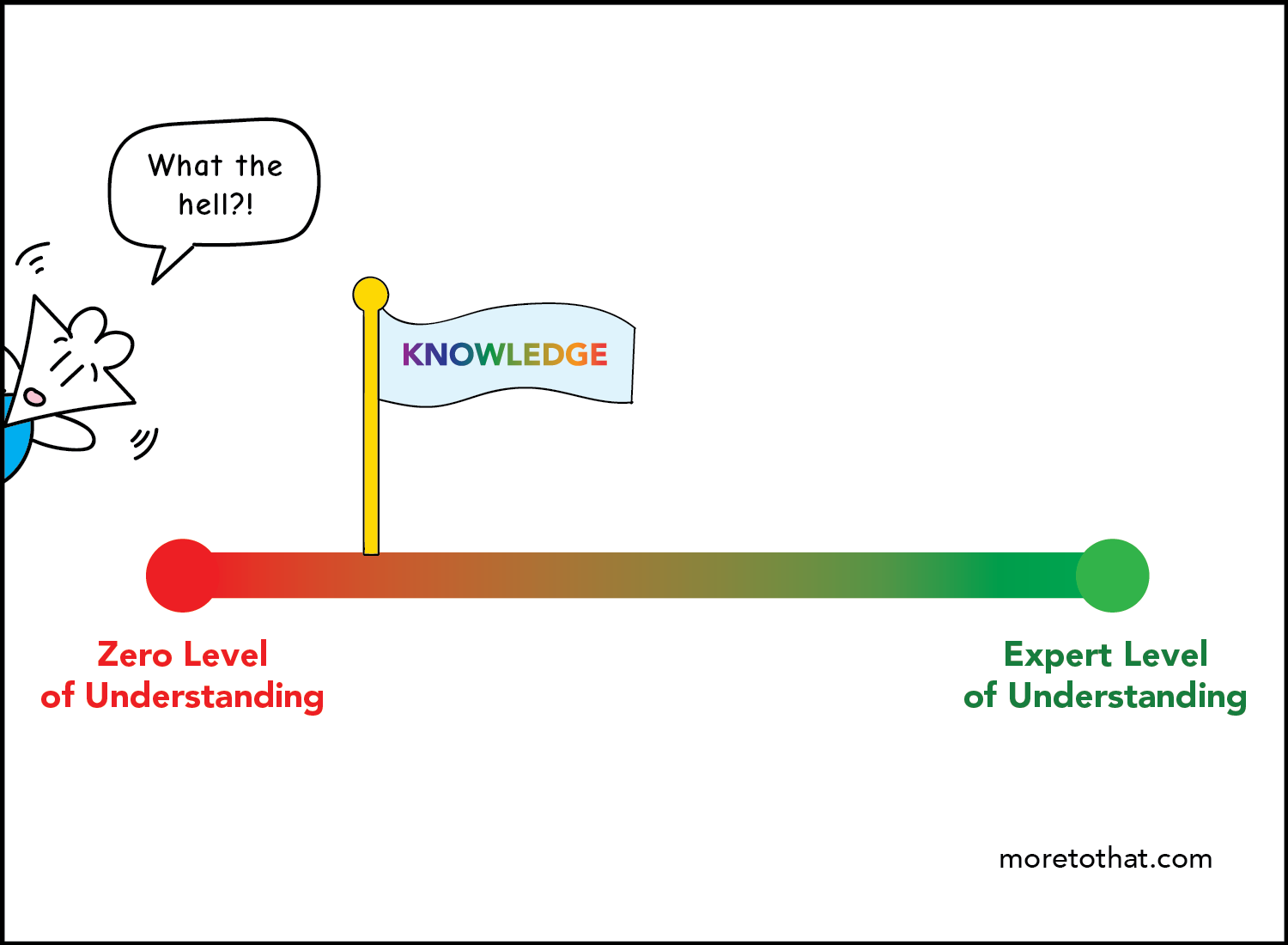

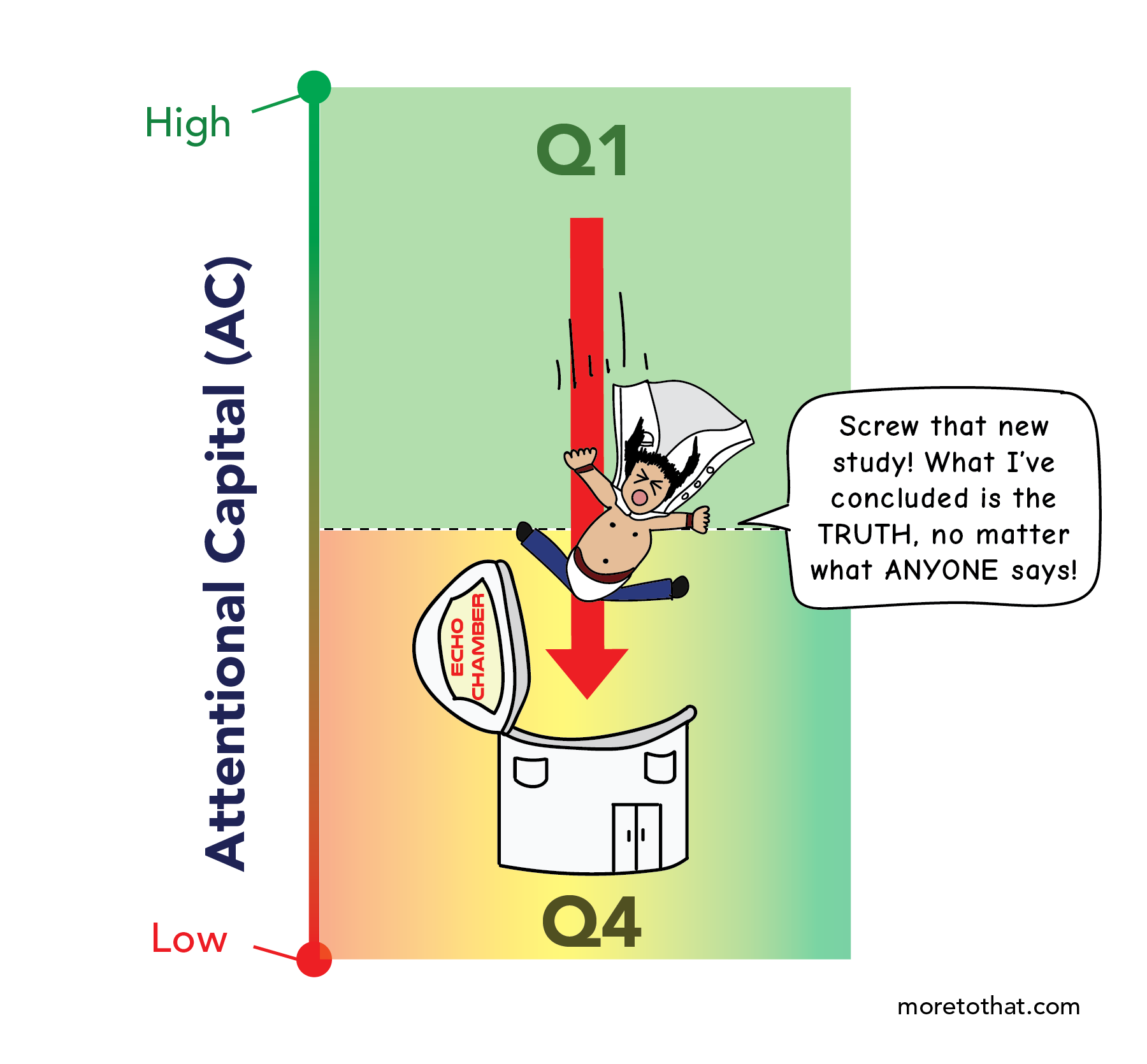

People that were once open and objective about their opinions may begin to harden their beliefs into an impenetrable wall, closing themselves off to an ever-changing world of opinions and new information. They believe that their level of understanding in this topic is high, but their attentional capital is so low because any objectionable evidence is immediately dismissed, and the only opinions that are tended to are those that align with their own.

In the context of our graph, this behavior represents a precipitous fall into Quadrant 4, where the walls of an echo chamber await their arrival.

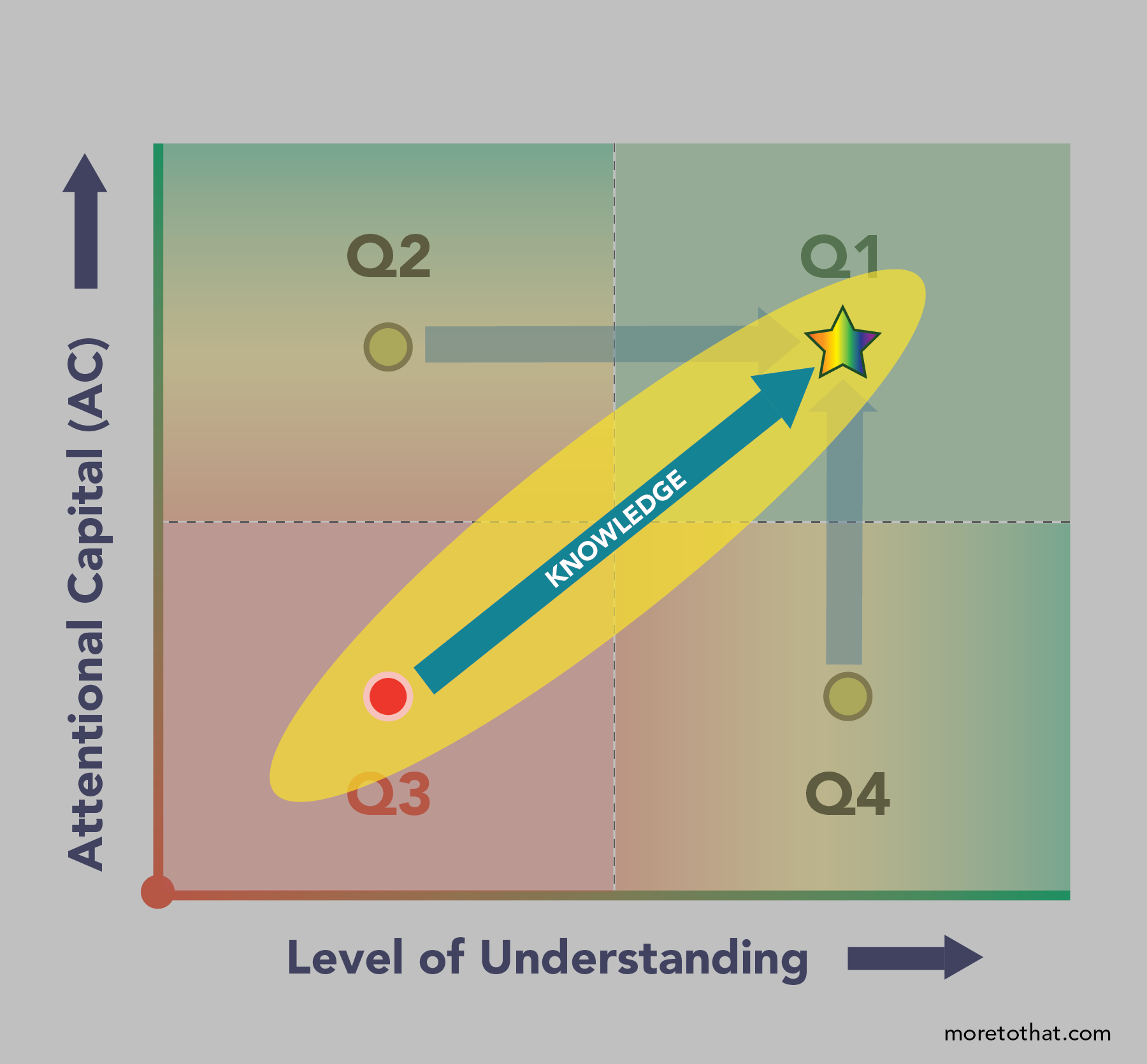

The truth is that none of us are immune to the movements between these quadrants. And since we are continuously in a state of flux between these states in so many topics, we cannot confidently state that knowledge lives at any one point on this graph.

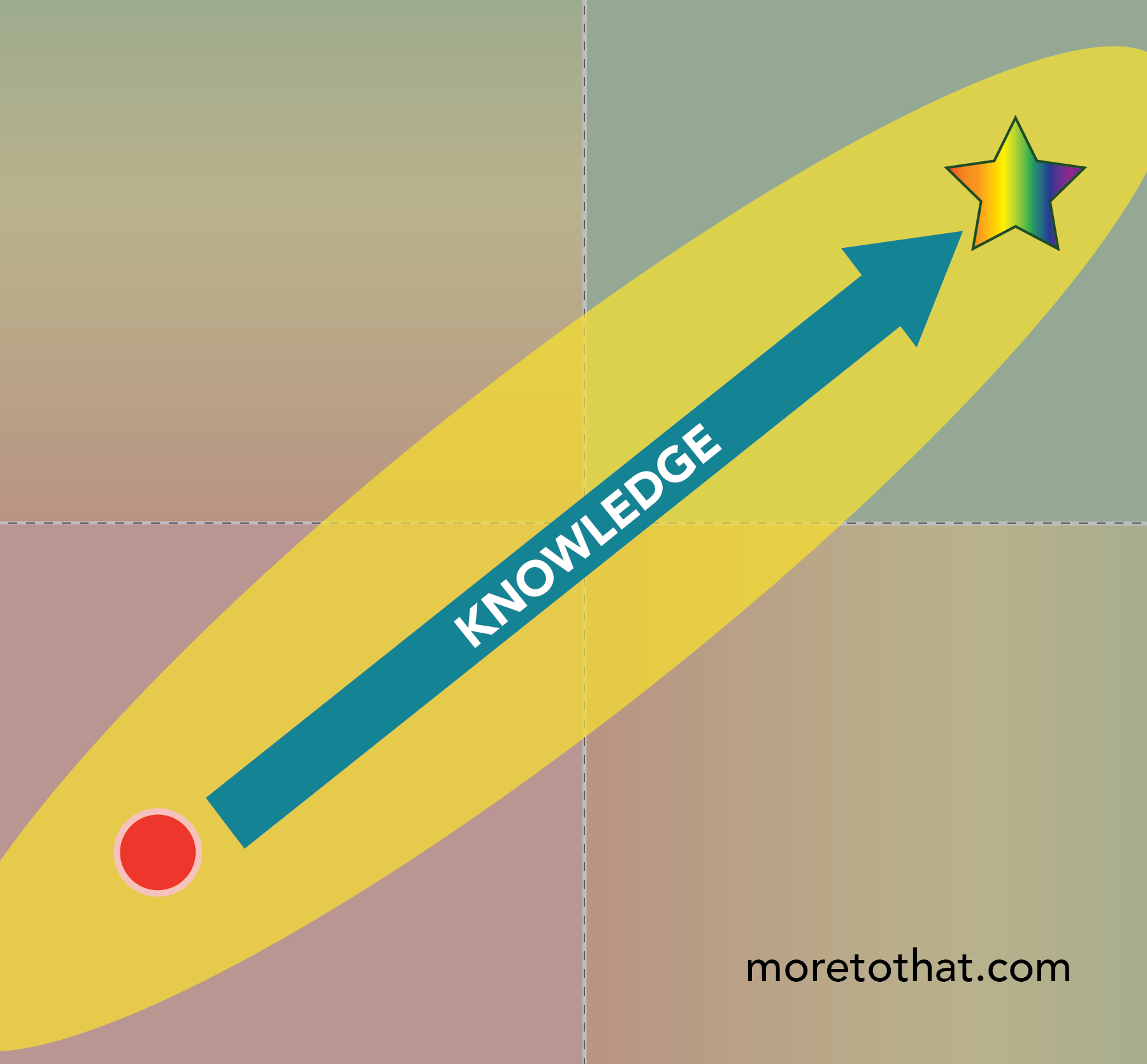

Instead, knowledge is the continual process we use to move into Quadrant 1. And once you get there, it also includes the staunch determination to stay in that quadrant for as long as possible.

When knowledge becomes a verb, it changes everything. We become highly aware of what state we’re in at any given moment, and can make a concerted effort to move to a place with a higher quality of attention.

We become aware of when we’re exhibiting low AC behavior, such as relying upon social media for our opinions (Q3) or refusing to engage in conversation with those we disagree with (Q4). We can also add humility into our process by admitting that we don’t know much about a topic, but are committed to being intellectually honest in our pursuit to learn more (Q2).

So with that said… how do we make our way into Quadrant 1?

Many people will likely have their own roadmaps, but I wanted to share a framework that has worked well for me thus far.

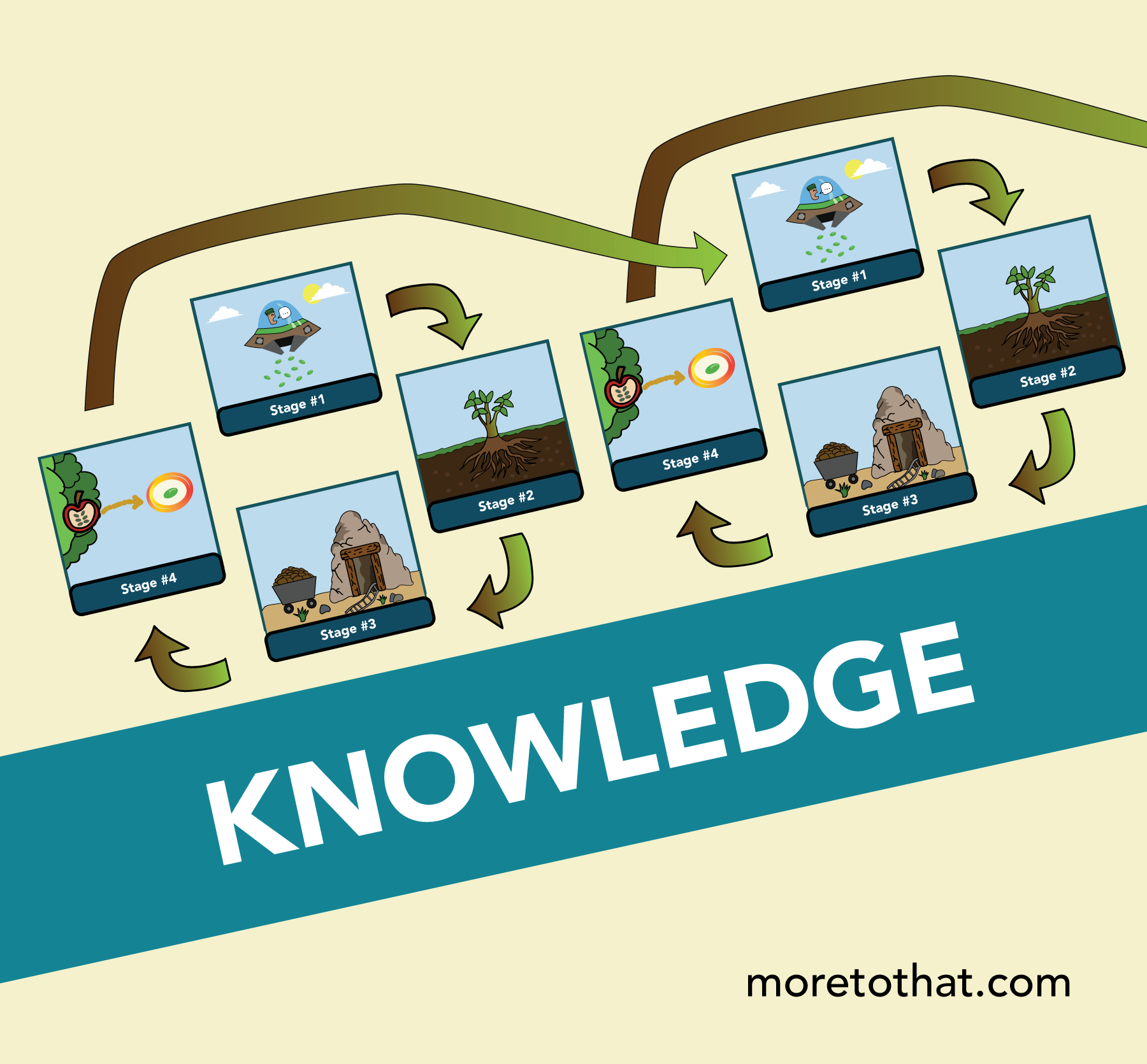

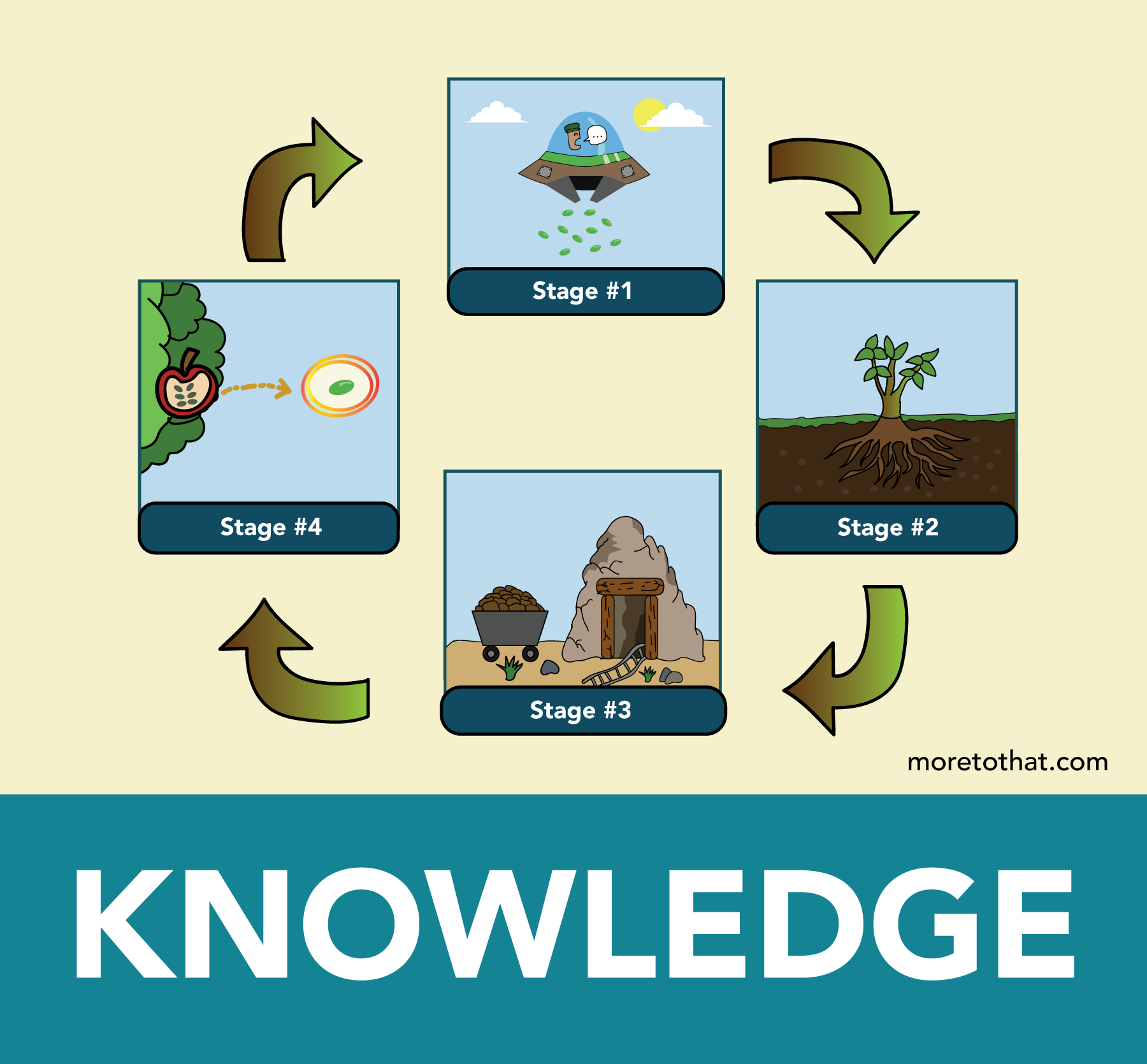

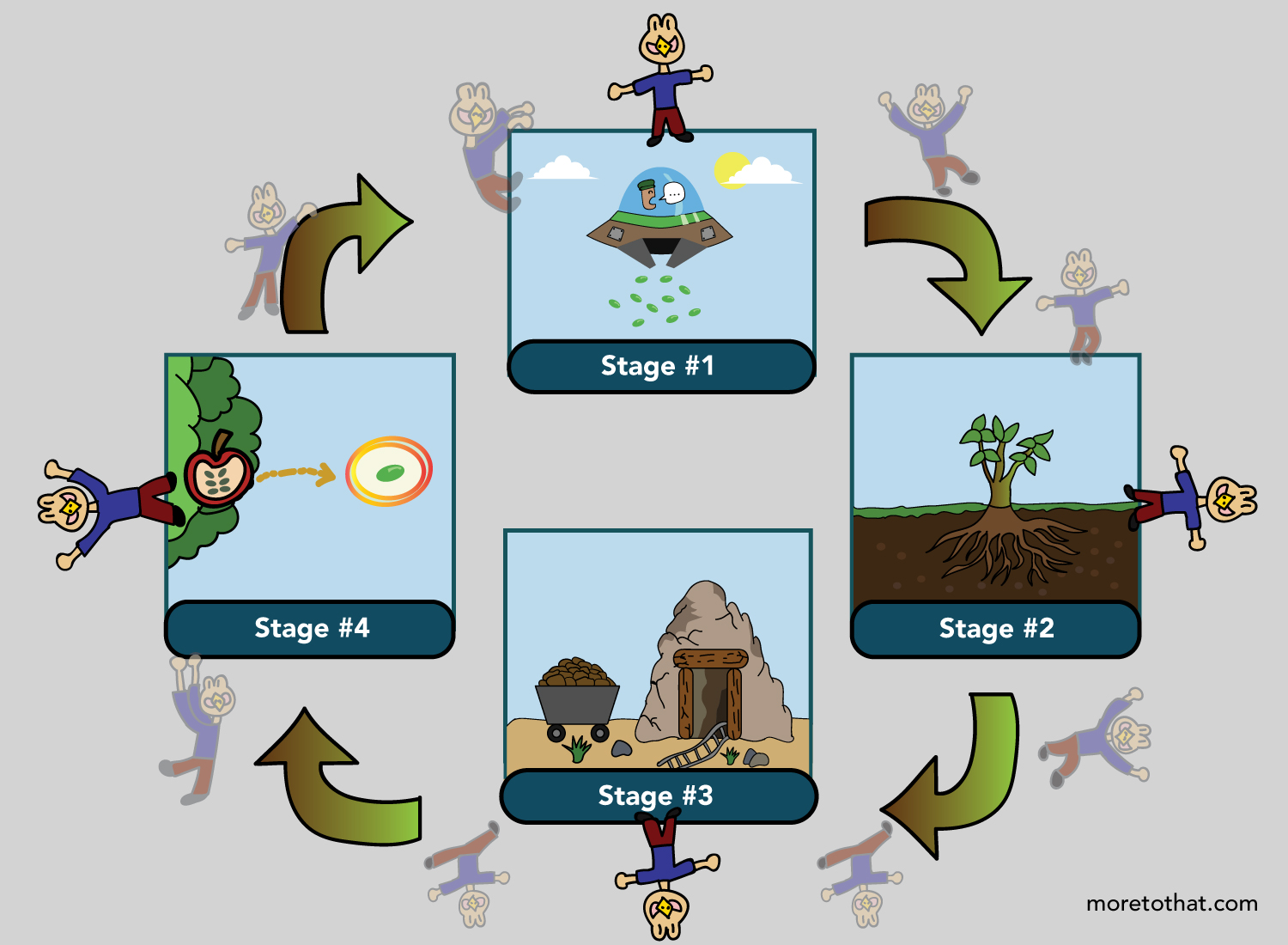

I find that when you zoom in on any one of the arrows leading to Q1, you see a continuous cycle of four stages that inevitably take you there:

This four-stage process is my framework for knowledge — my way of iterating on what I know and improving the quality of the information and opinions I have. And as long as this cycle is vigorously pursued, I know that I am trying my best to remain intellectually honest in my climb toward Quadrant 1.

So what does each stage mean, and how exactly does this cycle work?

Let’s dive in together and explore the details.

The Four Stages of Knowledge

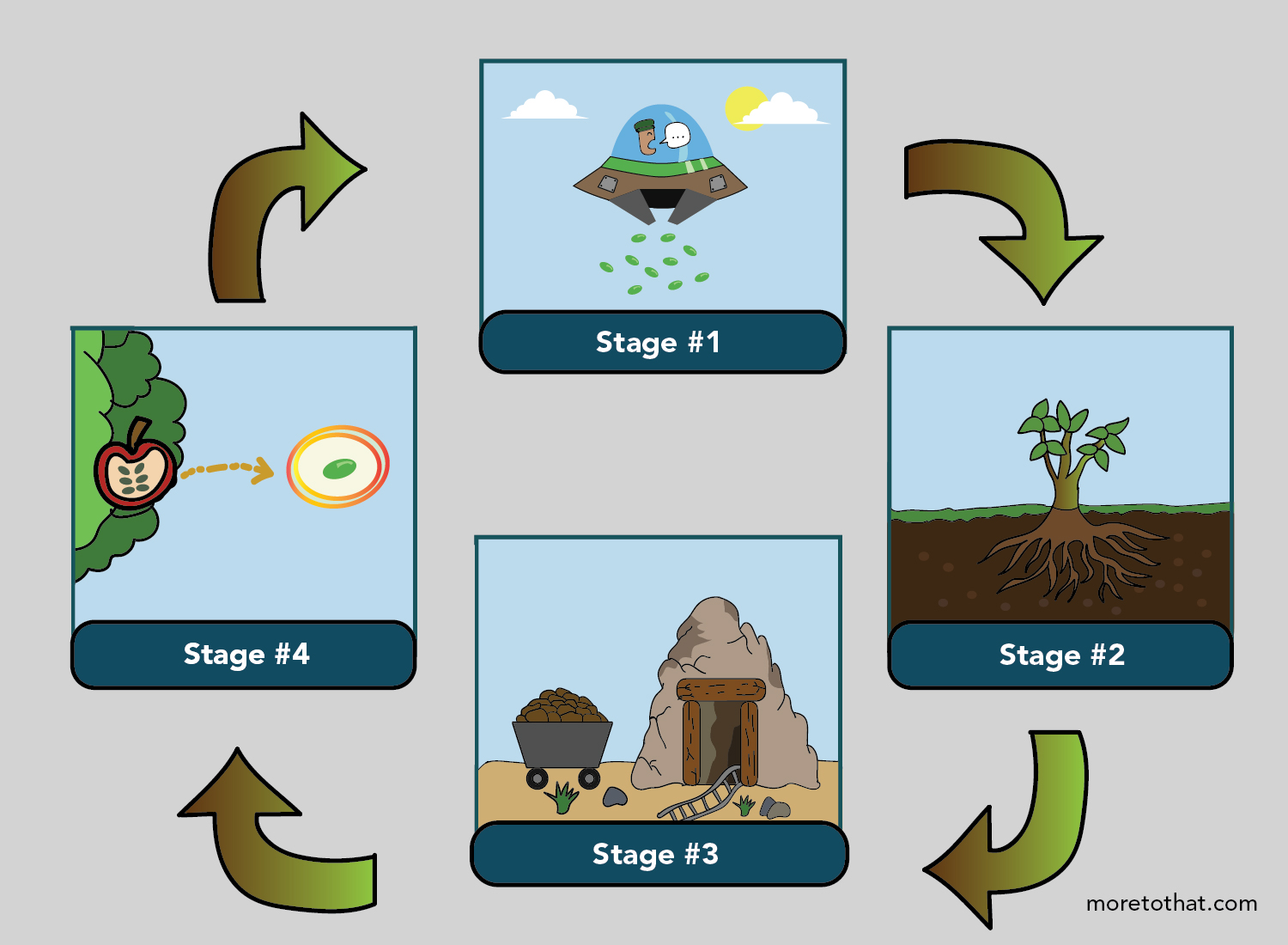

We will start with the first stage: awareness.

(1) Increase the quality of your awareness to find the best seeds

I have this thing where I like to imagine information as seeds — little kernels of ideas, news, or interests that have the ability to germinate into something greater if we tend to them.

These seeds are contained by large pods and capsules that hover over us everyday, each representing the different sources of information we come into contact with consistently. I call them information capsules. Some examples of these capsules can be:

- Conversations with mentors/peers

- Conversations with friends and family

- Podcasts

- Social media

- Blogs you follow

- News outlets

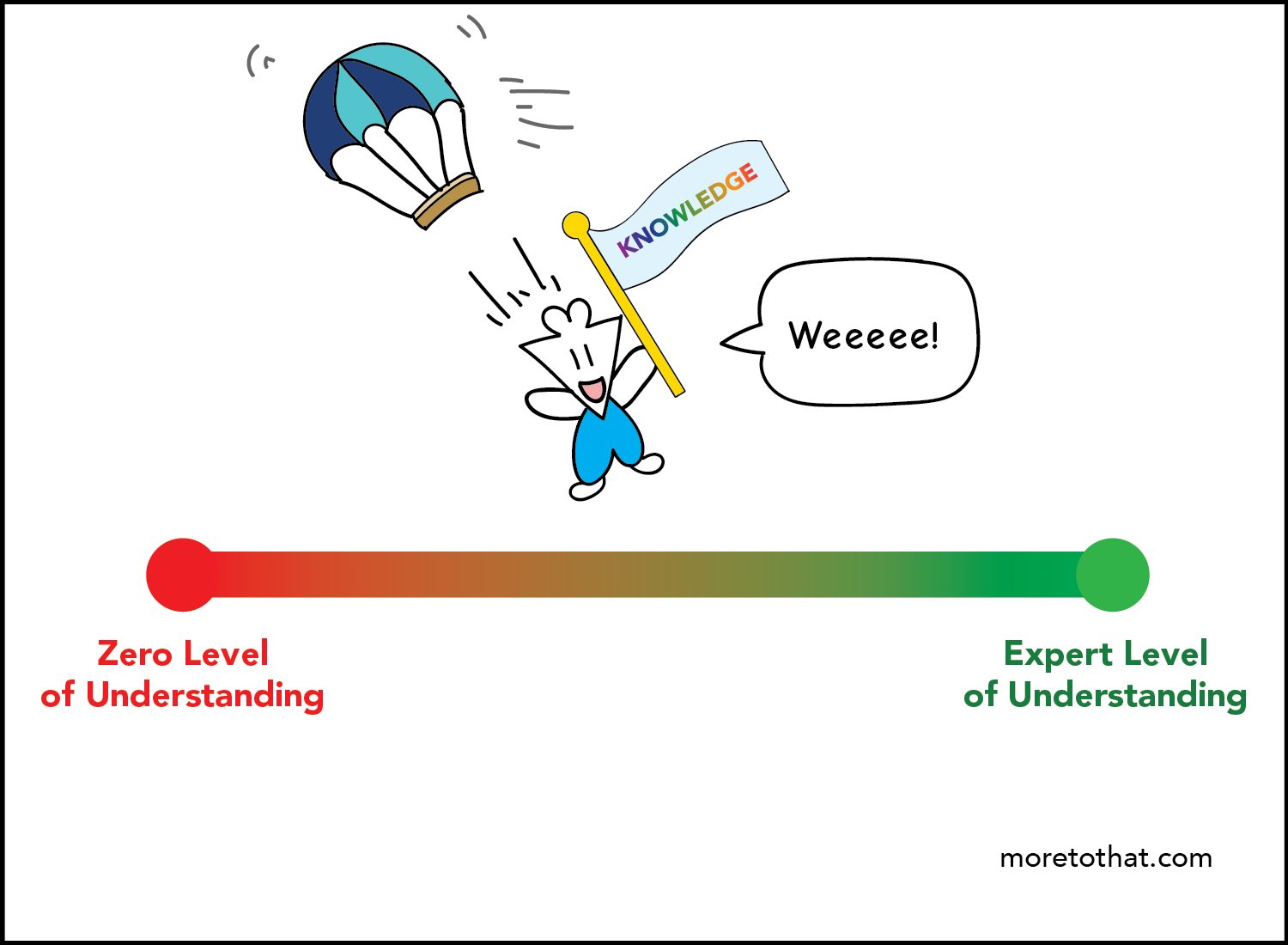

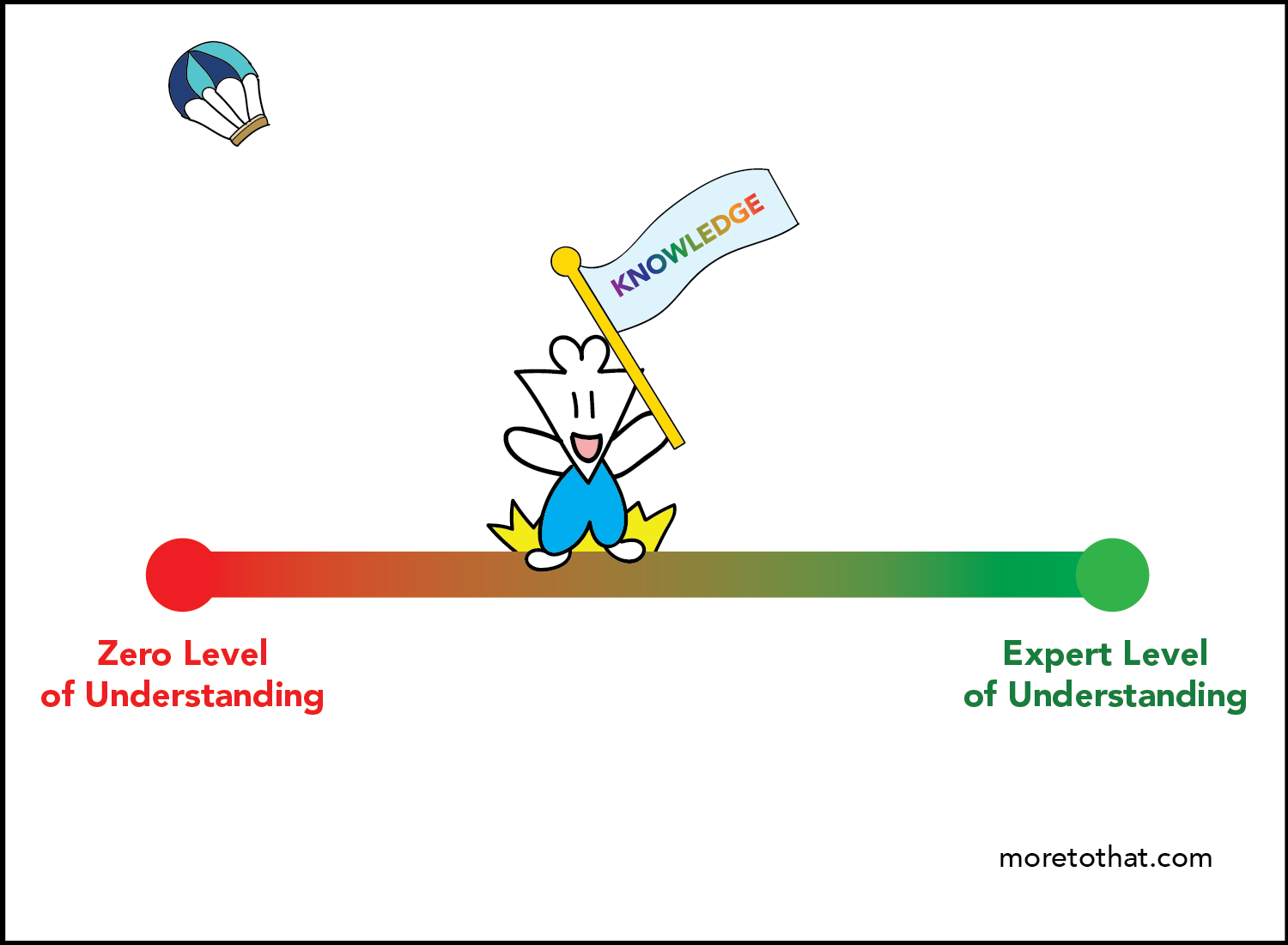

During the course of your day/week/month, these capsules open, and seeds begin to drop all around you and your field of awareness.

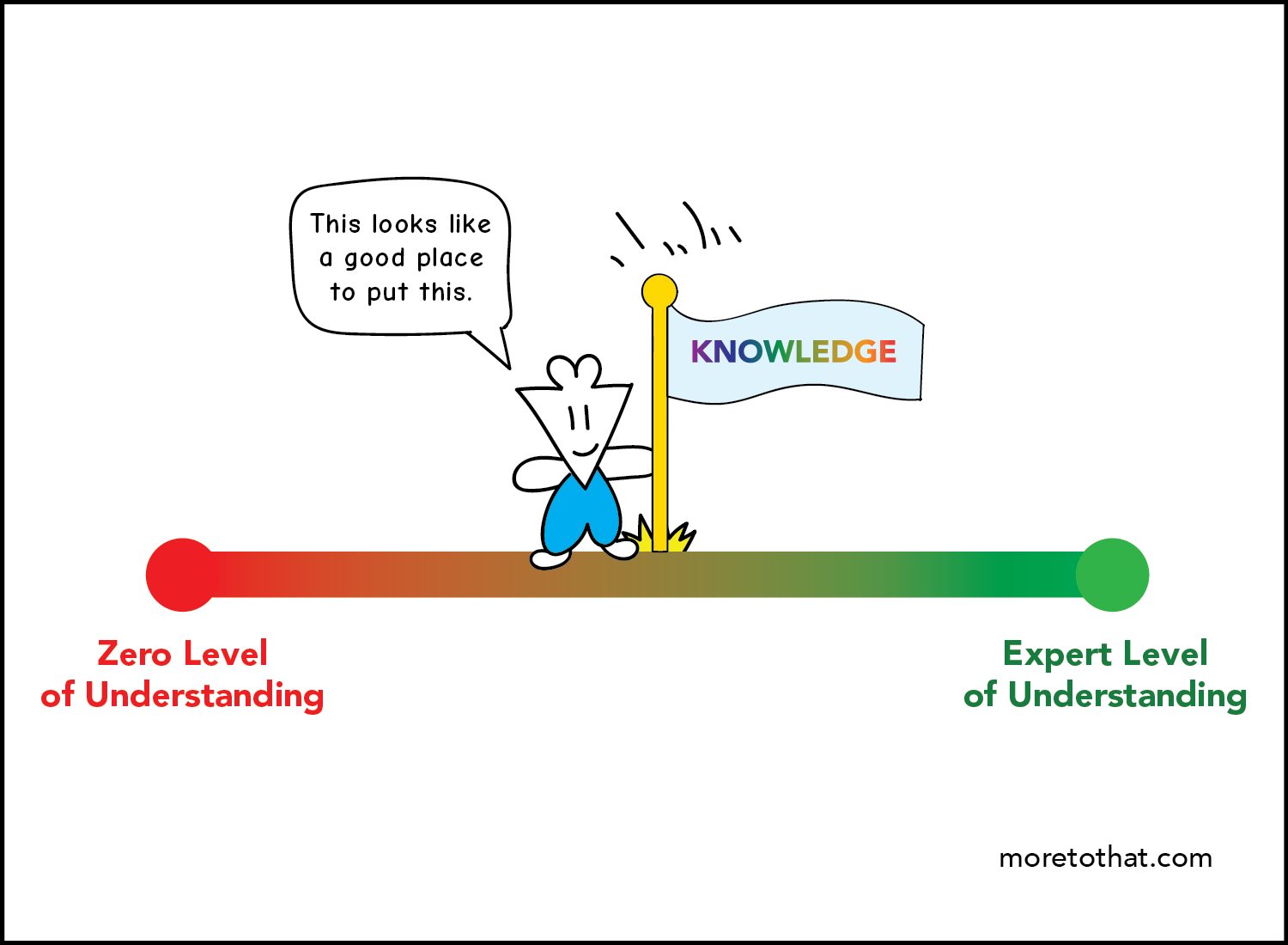

When these seeds are all around you, it becomes difficult to sort through them to find the best ideas. So the first thing I like to do is to prioritize the capsules in which they are deployed from. I personally find myself feeling super inspired after a fantastic conversation with someone, as the things we discuss are specifically tailored to our unique dynamic and shared interests.

If a mentor hears a current struggle of mine and recommends an idea to me, that seed will have a much higher probability of growing than a recommendation from my Facebook feed would. But conversely, a well-crafted tweet from someone I respect will be a much healthier seed to grow than that of a family member evangelizing the benefits of a job I have no interest in.

Using these experiences as a barometer, I like to adjust the doors on my information capsules so that only the highest quality seeds have the ability to reach me. There are some I leave wide open:

There are some doors I close:

And there are others that are only slightly ajar:

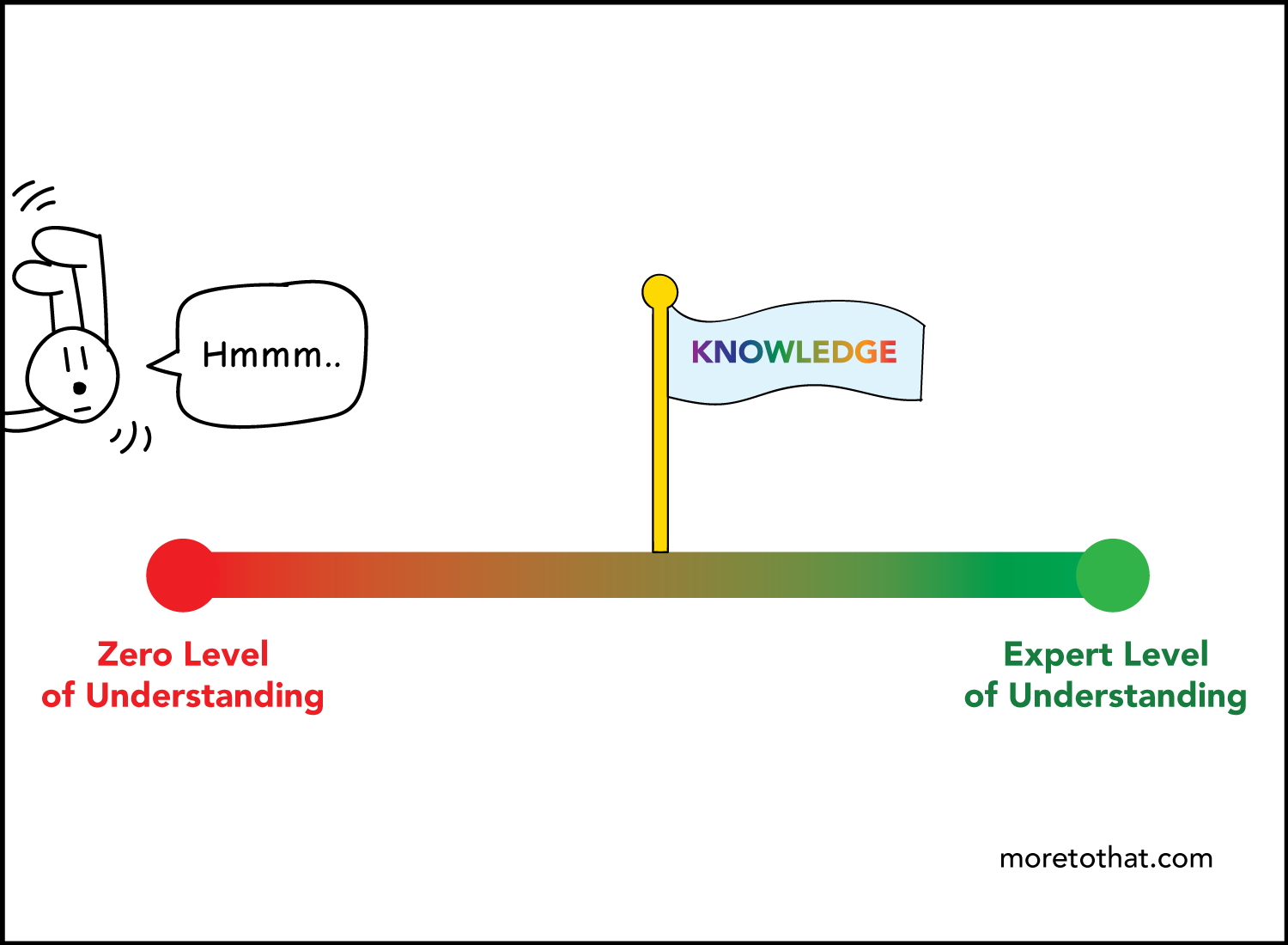

That way, a bottleneck of information is created, thus increasing the probability of a good seed hitting me and preventing most of the bad ones from ever seeing the light of day.

When you have more control over the information you receive, you increase the quality of awareness to good ideas, and lessen the impulsivity to prematurely act upon fleeting ones. This is the difference between reacting to information that elicit fear/greed/anger, and tending to a healthy seed using information based on logic/reason/intention.

(2) Cultivate curiosity to sprout and strengthen your roots

The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence.

-Albert Einstein

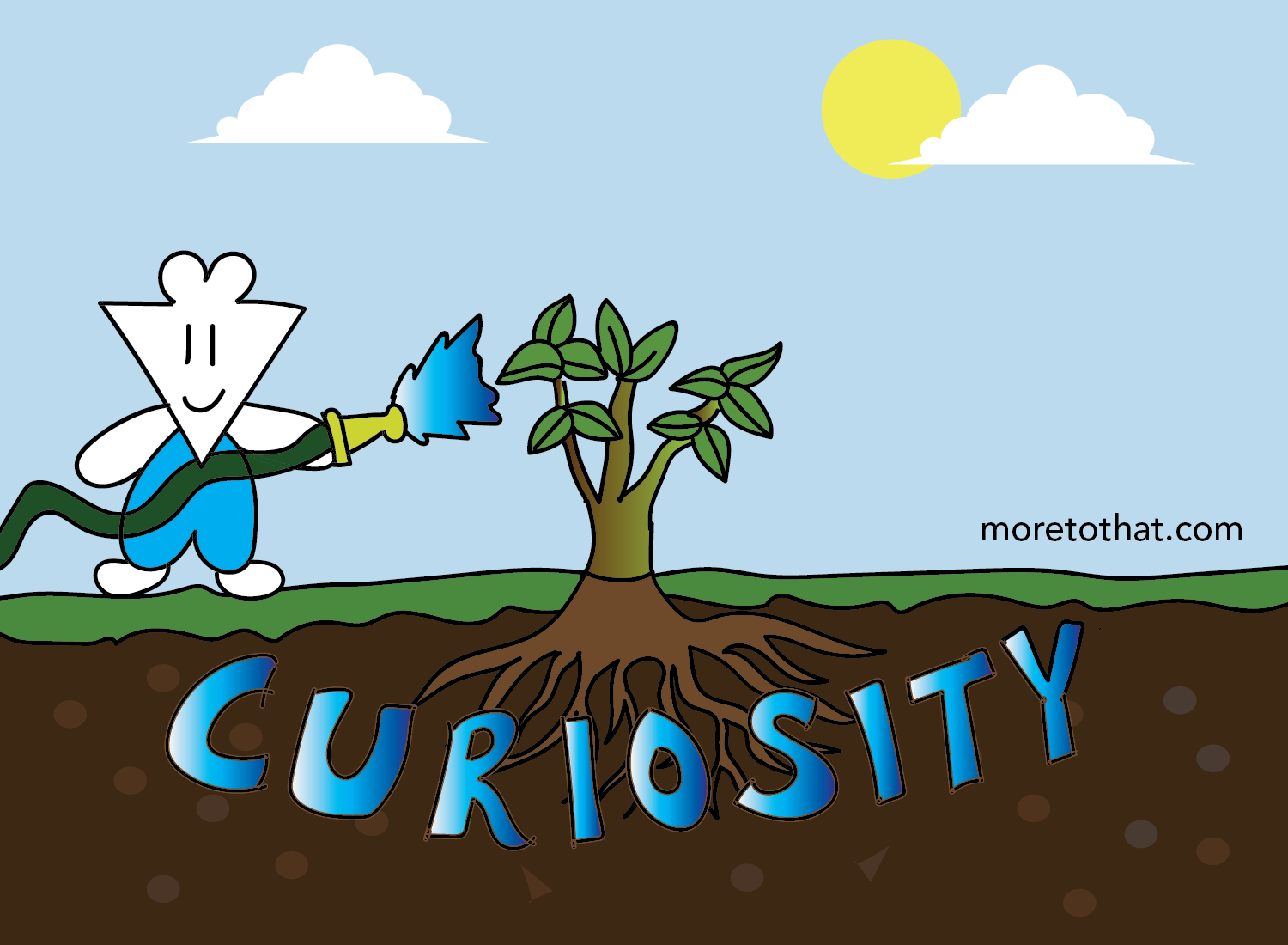

Once we select the seeds we want to grow, we shower it with the Mega Life Force. The Sultan of All Great Stuff. The Muse.

Our greatest ally: curiosity.

Curiosity is the triangular life force that propels us toward intellectual growth. It is:

- the soil we plant our seeds in,

- the water that allows the seed to sprout, and

- the roots that act as the foundation for its sustained growth.

You can have an absolutely masterful level of awareness for a great seed, but it won’t have the slightest chance to sprout life if you don’t ask any questions about it. For example, you can be made aware of the value of meditation by hearing someone talk about it, but that value dies if you have zero inclination to try it out yourself. Ideas only perpetuate when you have the desire to inquire within.

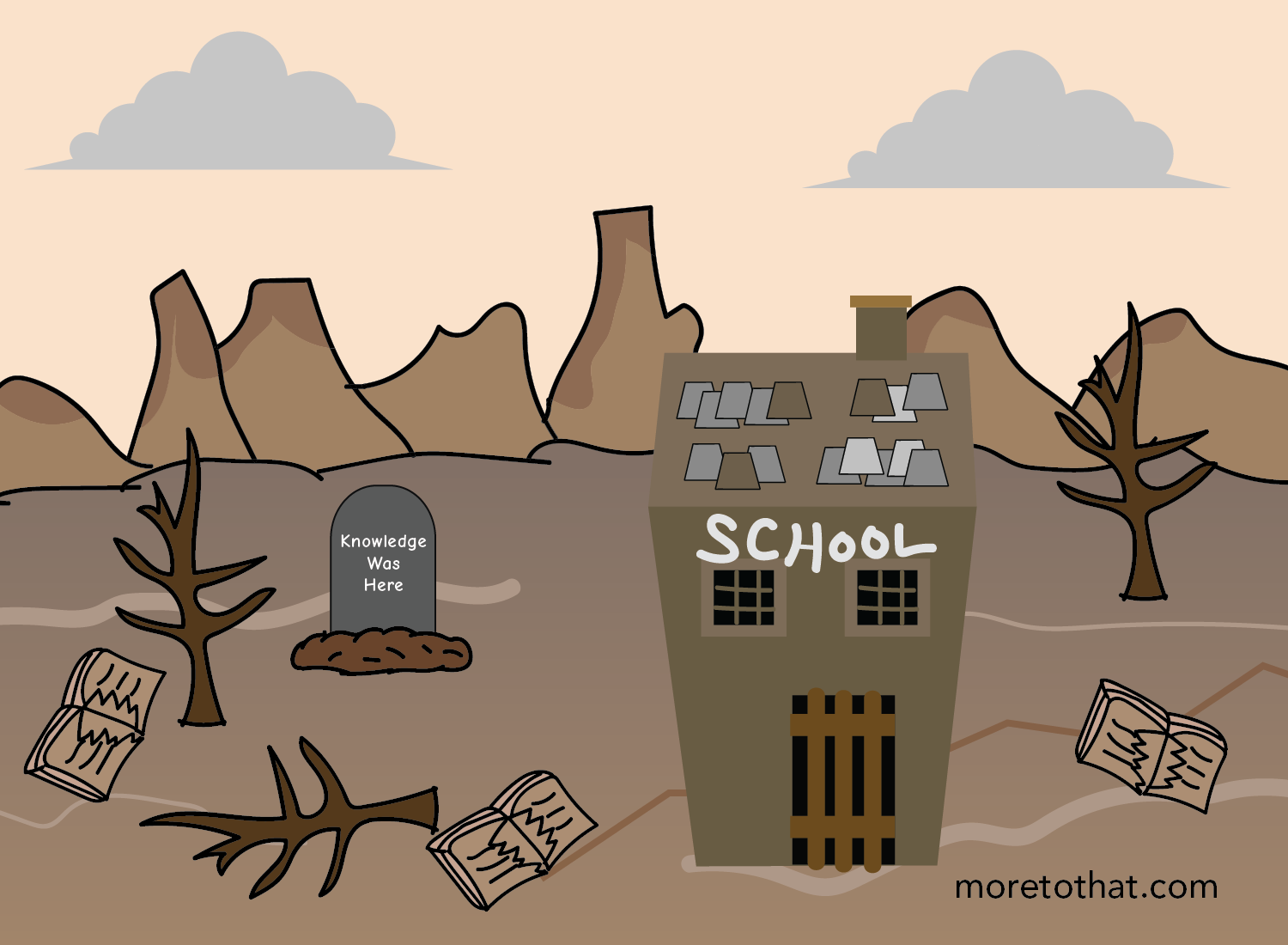

There is a common misconception out there that if you buy more books, build more schools, hire more teachers, or fill your head up with more stuff, then that will be the solution to our education system. This, once again, is the fallacy of treating knowledge as a thing — a noun. Vast swaths of information (or what we traditionally view as “knowledge”) and the venues that hold them will become intellectual wastelands if curiosity is not cultivated within them.

For example, if you’re a high school student (like I once was), believing that history is boring is about as commonplace as seeing a pimple on a 9th grader’s face. But a part of me becomes sad whenever one of these students says that about history. A big part of that sadness comes from the fact that I had a fantastic history teacher in high school, and because of his thoughtful framing of all these historical accounts, I found it to be an absolutely riveting subject. He was able to successfully cultivate curiosity in a subject that students typically disregarded as being lame.

This is just a tiny example of how it’s rarely the subject itself that is inaccessible. If you want to delve deeper into it, either you are already hungrily curious about that topic, or the gatekeepers of that subject (e.g. teachers, public figures, etc.) have done a great job in cultivating a culture of inquiry.

And once the condition of curiosity is fully satisfied, we can begin the process of growing the tree itself.

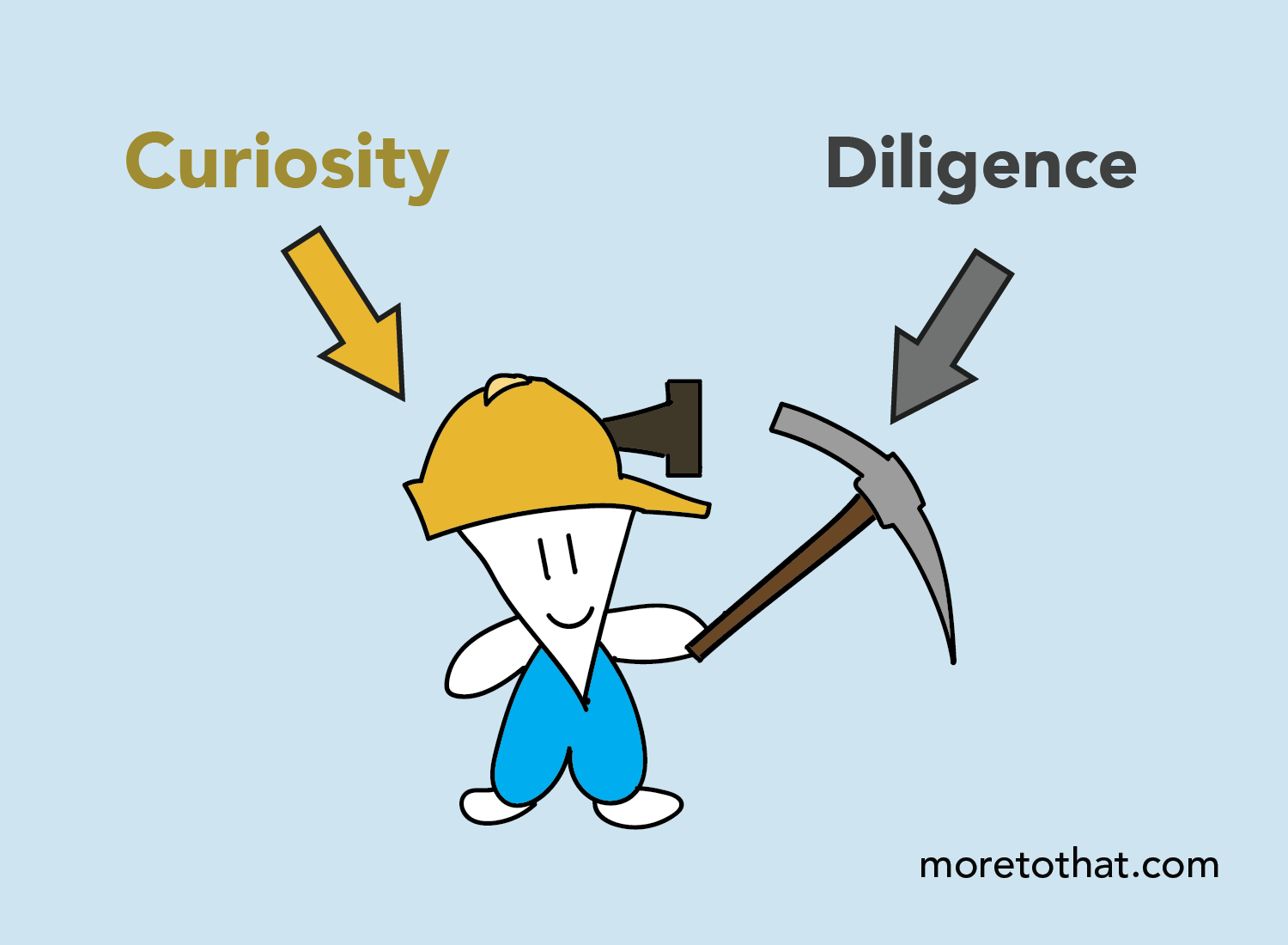

(3) Diligently mine information and build skill sets to grow your tree

You know that Albert Einstein quote I put up earlier? Turns out there’s a second half to it, and one that conveniently connects the prior stage to this one as well (thanks, Albie):

One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, or life, of the marvelous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.

-Albert Einstein… again

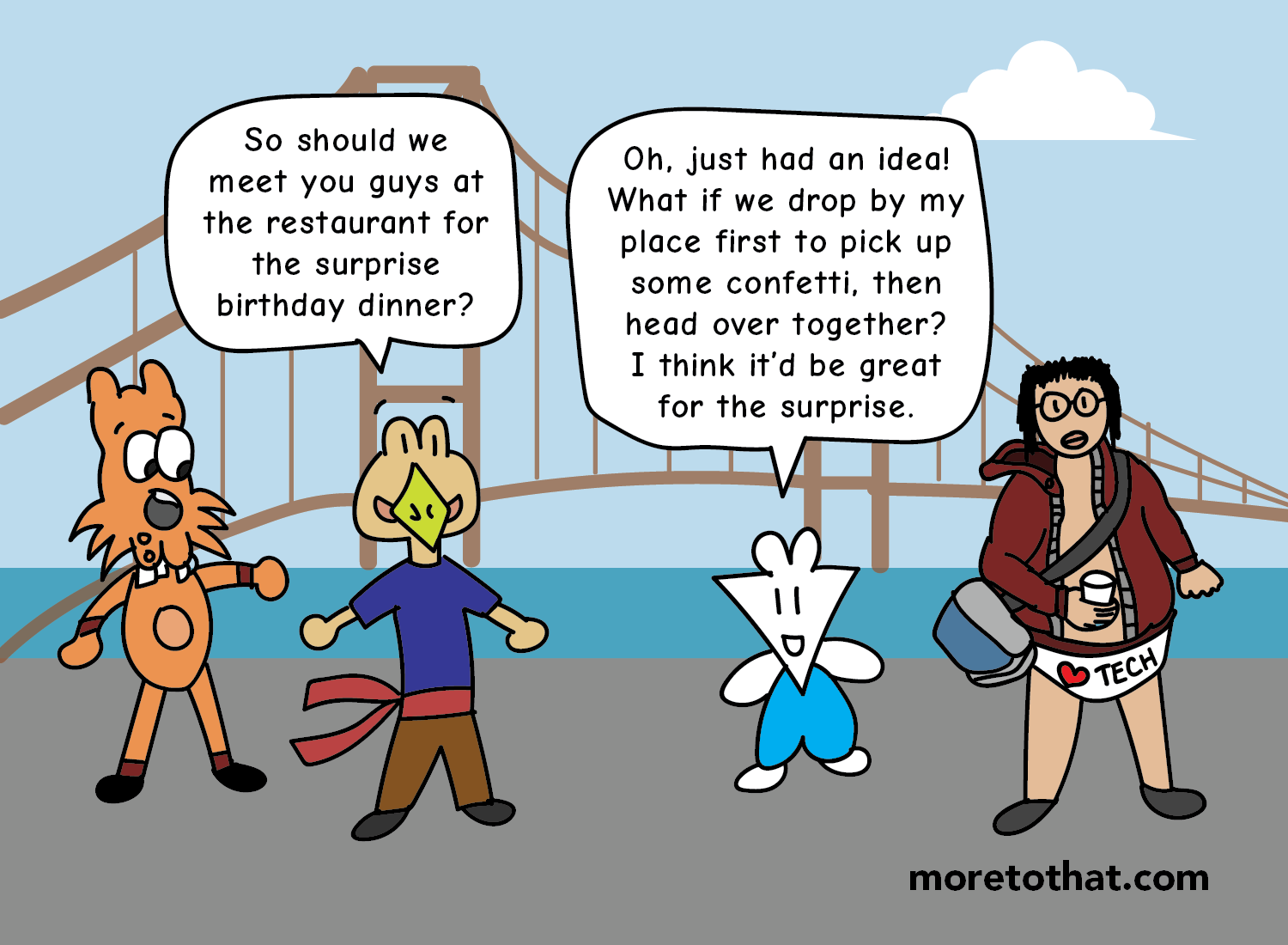

There is a saying in entrepreneurship that a great idea is worthless without execution. It kind of sounds like something a tech investor would condescendingly say to someone expressing an idea, but there is some merit to the (annoying) phrase.

In the same way that a “great idea is worthless without execution,” curiosity doesn’t become anything fruitful without diligence. Once we are curious about something, we have to begin researching, learning, and mining for relevant information that will help get to the bottom of our inquiries. This is the only way to continue the process of knowledge — without it, curiosity will become a hindrance to a clear mind. If your process stops with curiosity, then you’d be a perpetual space cadet, consistently in a state of wonderment of the world without clearing the space for actual dialogue about it.

This is the very reason why Albert Einstein ends his thoughts on curiosity with that last sentence: “It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.”

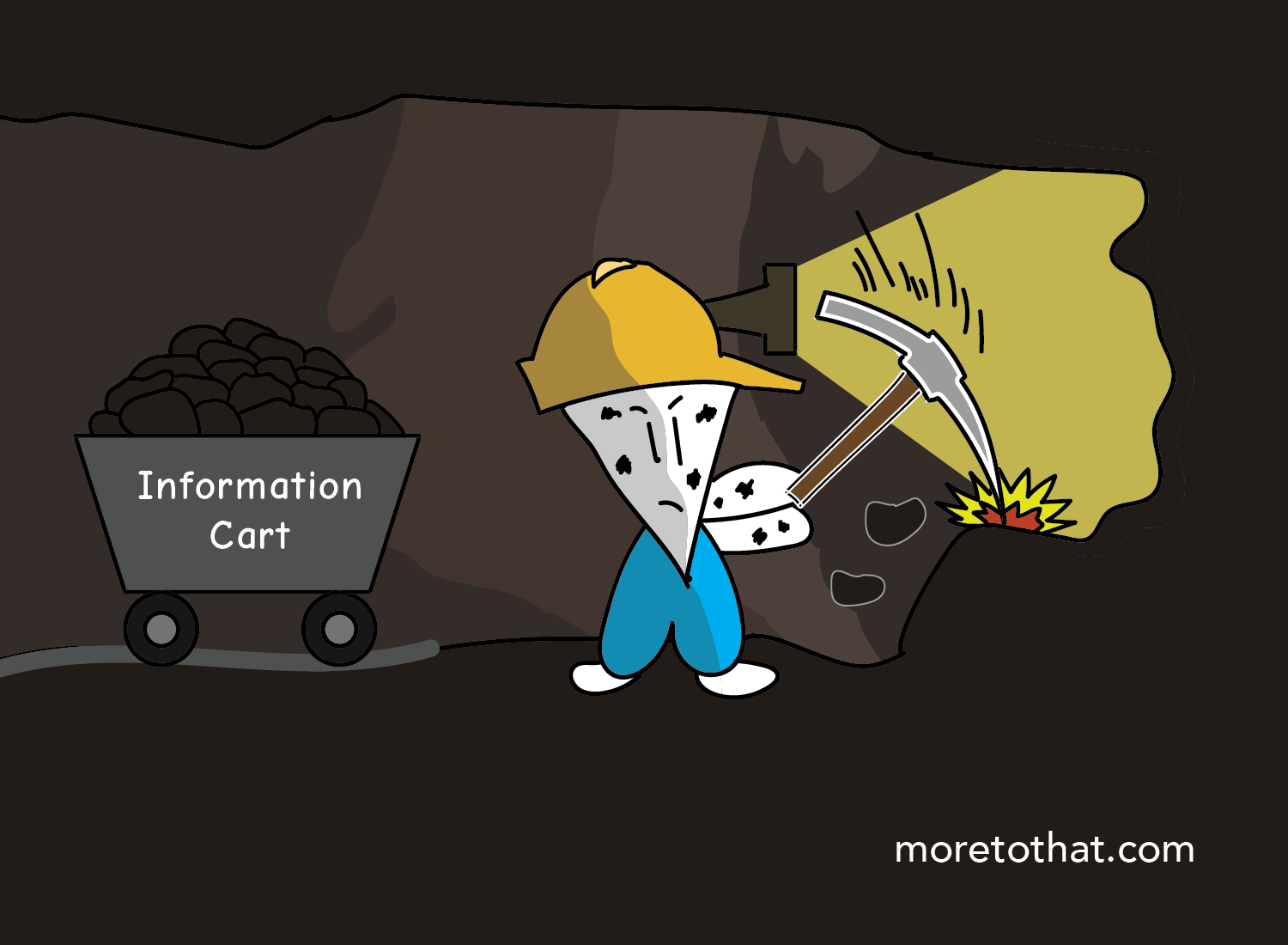

He doesn’t say that we should continue to stay in mouth-gaping, perpetual wonderment about the mystery of life every single day. No — even if it’s past the realm of our understanding, we should still attempt to remove as many layers of the mystery as possible. We must enter the Mine of Potential Answers, with Curiosity as our head lamp and Diligence as our pickaxe to tirelessly extract the information we need to satisfy our questions:

And at the end of each day, the extracted information is collected, processed, and funneled into the roots as nutrients, which then grow to become the building blocks for the trunk of our tree:

As questions find answers, better questions start taking their place, thus raising the overall quality of our curiosity as well. For example, people introduced to bitcoin for the first time may ask, “What is bitcoin and why is it special?”, which is a question that millions of people have. But if they spend some time and effort in closely studying it, their point of curiosity may evolve to “How do we solve bitcoin’s carbon emissions problem as the computational power required to mine it continues to grow?”, which is a question far fewer people ask but is much more relevant to the viability of the technology.

As we continue to diligently mine and research more information to satiate our curiosity, stronger curiosities arise to further our quest to remove more layers to the mystery. It’s a beautiful self-reinforcing cycle that eventually perpetuates itself to the final stage of knowledge.

(4) Produce and distribute seeds of your own to constantly iterate on what you (think you) know

As we use curiosity to anchor us in our quest to build our tree, we will inevitably create assumptions about what we have gathered. Our intuition is a powerful force that allows us to decipher whether or not something we read/hear/view feels right (or feels true), but it can definitely misguide us as well. So in order to test and ultimately spread the quality of what we know, there are two things we can do:

(A) Discuss our findings with those we respect to get feedback and ensure the integrity of them, and

(B) Distribute what we know to others in the form of education.

Point A provides us with the space to vet our ideas and thoughts about the tree we are building. Your tree has grown to a point where it can produce a seed of its own, and this seed has been carefully cultivated through research, experience, and applicability. Before it is deployed to others in the form of education, it is important to share that seed with those you respect so your ideas and findings are kept intellectually honest.

Dialogue and an earnest exchange of ideas are the best way to refine and test your assumptions properly, which will further increase the probability of your own seed growing into someone else’s tree.

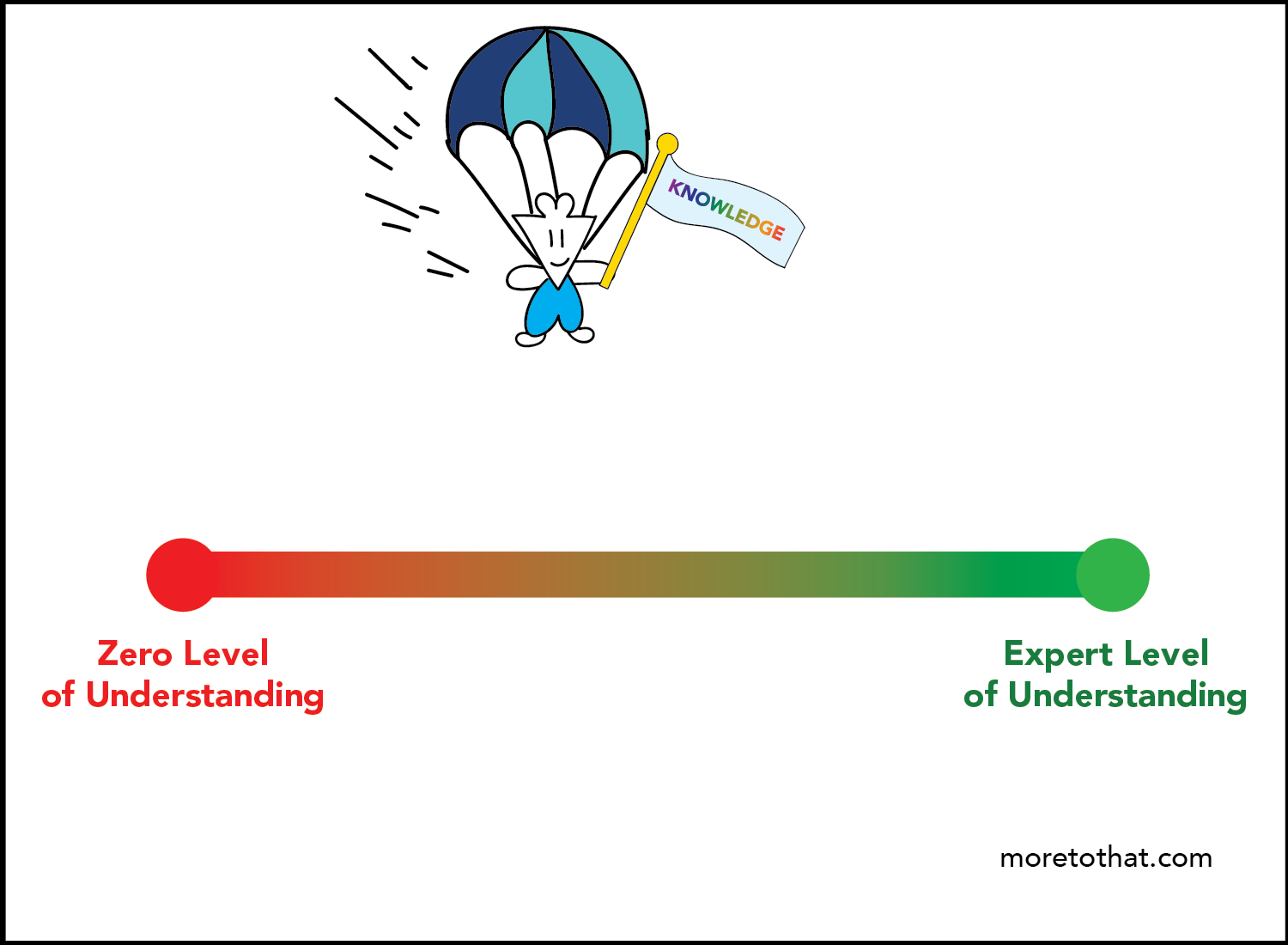

Point B, or the process of education, is a fun and deeply engaging step, but it’s also the most frightening one of them all. This is when you get to build your own information capsule — the same type of information capsule that gave you the initial seed to start you off on your own journey (Stage #1).

This capsule will allow you to distribute your own well-cultivated seeds to the general public, but this requires a lot of creativity to get it done right.

What strategy will you employ to distribute what you know? How do you want to bring people into the excitement you felt throughout the first three stages of knowledge? Maybe by creating an interesting podcast to convey your thoughts? Or by writing a blog post perhaps? Or by carefully formulating your findings so you can introduce them in any conversation?

The possibilities here are endless, and fun to navigate through as well.

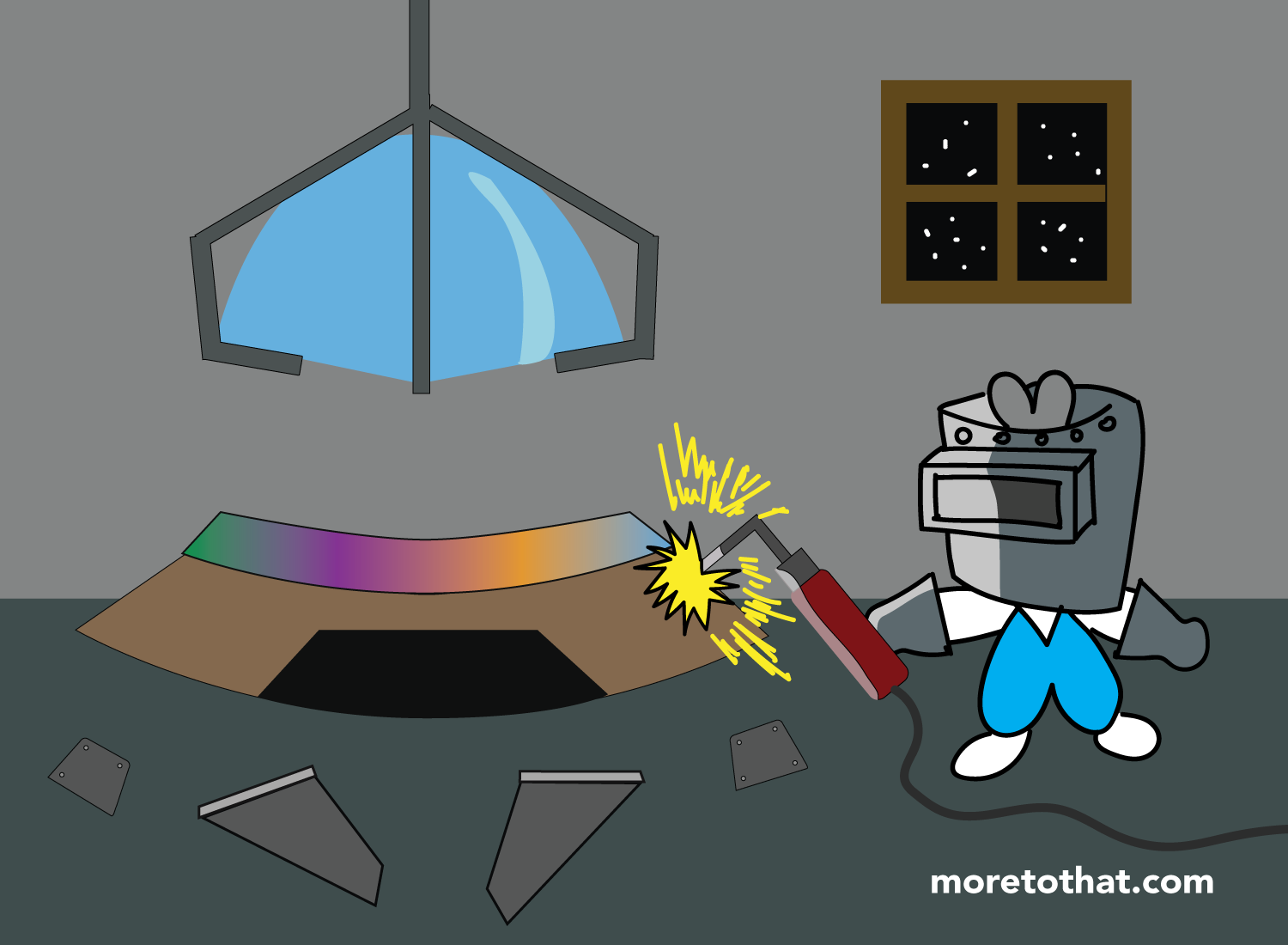

But on the flip side, this step is frightening because like all things we build, they can fail miserably. The information capsule you build can crash violently if the seeds in it are bad or if the capsule itself is poorly constructed.

Trust is the fuel of every information capsule out there. If you distribute seeds of misinformation or malice to people, then trust will no longer be provided to you, and your capsule will come throttling down to the ground in a ball of fury. This is why it’s important to do all of the preceding steps (maintain curiosity, conduct research, have discussions with others) to ensure that a high-quality seed will be distributed.

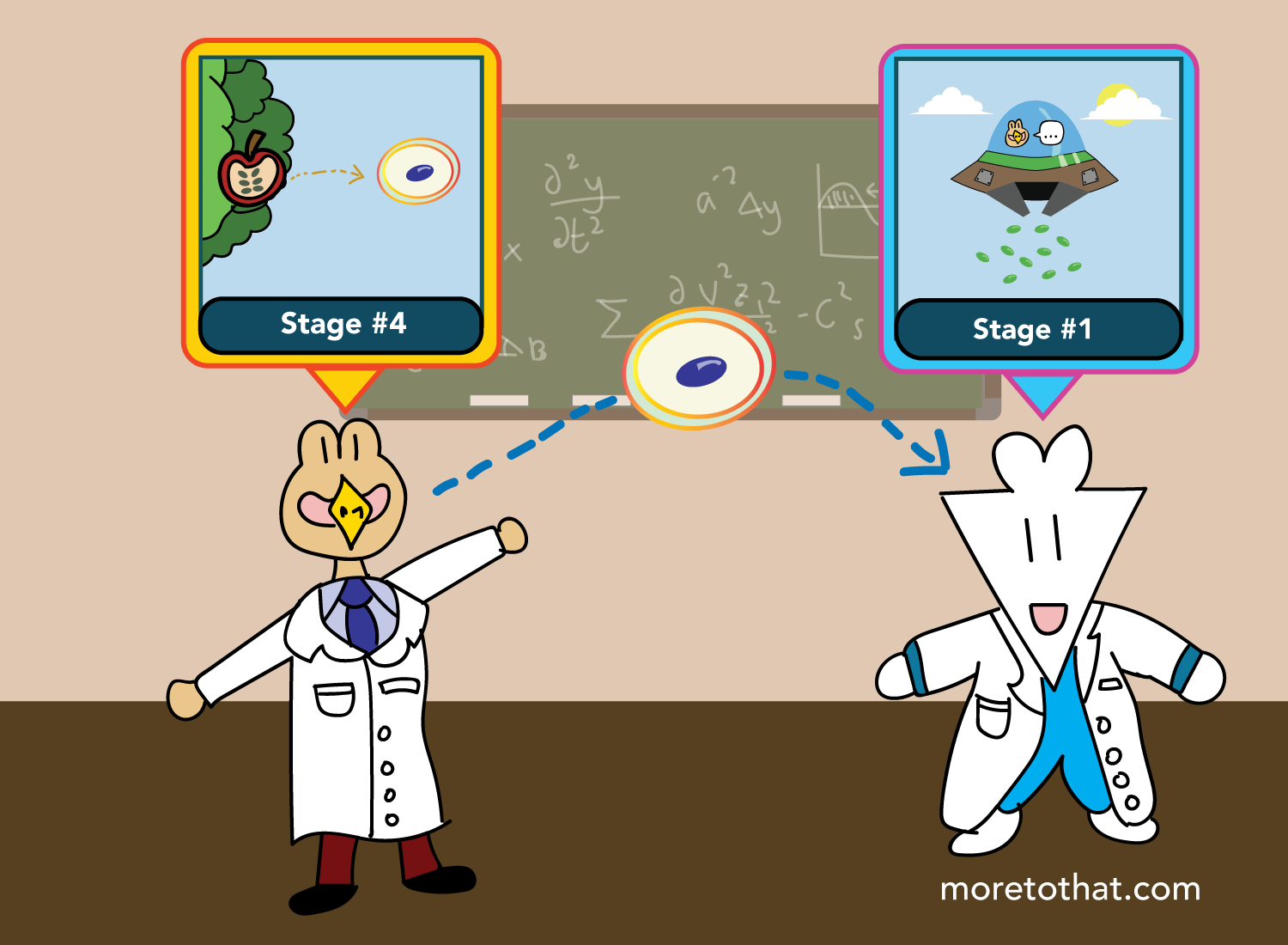

However, a high-quality seed doesn’t necessary mean that it will retain its accuracy over time. Although a seed should reflect what you know to be true, other opinions, rebuttals, and theories can push you to rethink your conclusions.

This is what education is all about. When you take the time to spread your findings to people, you simultaneously create the opportunity for a revision in your thought process as well. This is the root behind the adage of “teaching being the best form of learning.”

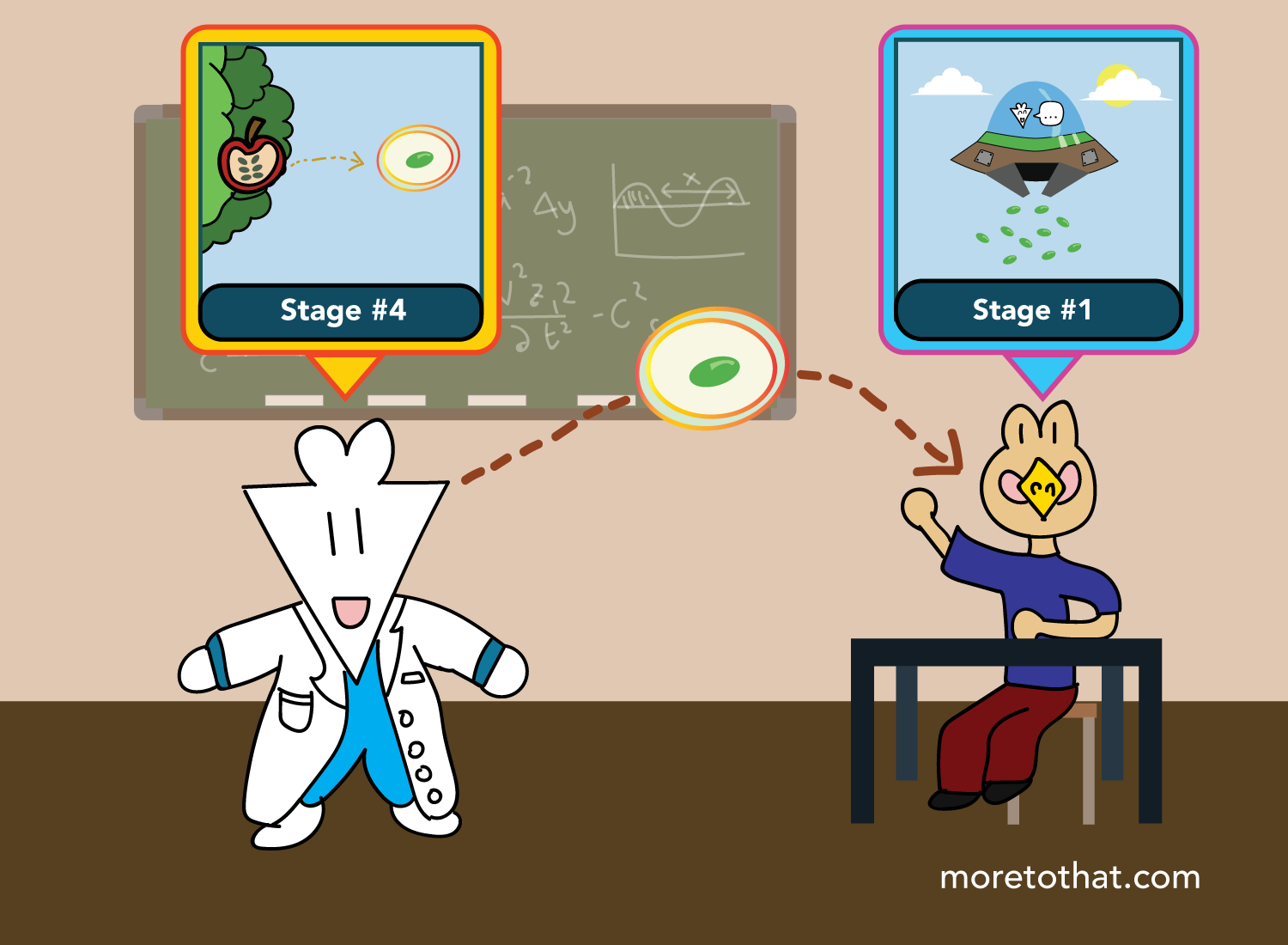

The way it works is quite simple. The seeds you disperse in Stage #4 become a new seed of awareness for someone else’s Stage #1:

This then starts the recipient of the seed on their own process of knowledge, which takes them around each of the four stages that comprise it:

The conclusions that one has on this journey will ultimately be spread through their own Stage #4, and if they are unique enough, has the potential to be made aware to you in your new Stage #1.

This iterative approach to knowledge is the whole basis for scientific/artistic/entrepreneurial discovery and pursuit. There is a constant cycle of construction, destruction, revision, and re-introduction that is perpetuated through curiosity and education. And through this process, we continuously test our assumptions, iterate on what we know, and unearth just a little bit more of the vast unknown.

This cycle is what it means to knowledge (as a verb). It’s the constant movement from awareness to curiosity to diligence to distribution, and back to awareness, where the cycle starts over again.

Knowledge is not something to be rigorously acquired, it is an action to be consistently practiced.

Wisdom Lives Between the Noun and the Verb

The acquisition of learned habits, techniques, and information is useless without something called wisdom. And gaining wisdom means much more than increasing our ability to retain information.

Wisdom, as I define it, is the combination of the following six pursuits:

- discovering new things,

- learning more about these things,

- using these things to improve one’s treatment of self and others,

- being honest about what is known,

- being honest about what is unknown, and

- establishing trust by doing what is right.

Wisdom is what resides between the view of knowledge as a noun and knowledge as a verb. And between this space is an abundantly clear point:

Knowing more stuff does not make you wise — rather, it is the way in which you use what you know that does.

My framework for gaining wisdom is by moving through each of knowledge’s four constituent steps, and more importantly, by starting all over again. It keeps me intellectually honest in my pursuit of information, as I am continuously reminded that my ultimate goal is not to become more “knowledgeable,” but rather to equip me with what I need to become a better, more compassionate, and more inclusive human being.

The purpose of this post is not for you to correct someone every time they use knowledge as a noun. That would, in fact, be a super unwise thing to do. Instead, it’s meant to suggest a framework you can point to every time you’re in the process of learning more about the world. Knowing that knowledge can only perpetuate through dialogue and education (Stage #4) allows me to take a step back and view the underlying intent of what I’m pursuing in the prior stages. If the ultimate goal is for me to build an information capsule of my own, only the good seeds should hold space there.

With this in mind, I can start asking some powerful questions every step of the way. For example:

If I’m in Stage #1, or the Stage of Awareness, I can ask myself:

Which of these seeds around me hold kernels of truth that will be beneficial to cultivate? Will my awareness of this fact contribute positively to the well-being of myself and others?

If I’m in Stage #2, or the Stage of Curiosity, I can ask myself:

Given curiosity’s stance as a valuable resource, what topics allow me to craft the best possible questions I want to explore? Will I be open to exploring things that I don’t agree with if they are indeed true?

If I’m in Stage #3, or the Stage of Diligence, I can ask myself:

What is my motive for all the research and hard work I’m putting into mining this information? Is it purely for self-gain (fame, fortune, status)? As I’m learning more and more about this topic, is it something that is in line with my values, i.e. would it make me happy to be a proponent of this in front of those I respect and admire?

And if I’m in Stage #4, or the Stage of Education, I can ask myself:

Am I effectively representing the things in which I know to be true? Am I open to changing my beliefs based on the quality of feedback I’m receiving in response? Am I a walking testament to the ideas and arguments that I am proposing to the world?

One thing I’ve realized is that questions often bring you closer to wisdom than answers. This is just an inherent part of the way our universe works. Our universe is simply too vast and unknowable that it is impossible to have more answers than questions to our greatest curiosities. And even if we do become subject matter experts in any given field, we have only found a few answers in a small subset of a tiny, tiny corner within this infinite expanse of ideas.

So a goal dedicated to knowing everything about the world is fruitless. Instead, it’s about finding the small corners and crevasses in the landscape of curiosity that we can deliberately delve deeper into. And in this process, the mindful discarding of information is just as important — life and curiosity is too important to waste on bad ideas.

This is our one life to live — our one at-bat in the stadium of human existence. All the knowledge we have in our minds will dissipate with the last breath we take, but the seeds we have distributed through wisdom will continue to take form and grow into trees of their own.

Knowledge as a thing is temporary, but knowledge as a framework is everlasting. It’s that humbling thought that drives my curiosity every step of the way, and the central seed I want to share with this small information capsule of my own.

Note: This post marks the conclusion of a two-part series on the topic of knowledge. If you’d like to check out the first post in this series (“Knowledge Is Not a Thing”), you can do so here.

_______________