The Four Ancestral Wants: A Brief Dive into the Nature of Desire

The world is not how we want it to be, but that’s precisely what makes it so special. Much of what makes life interesting is the fact that our individual desires are often misaligned with the movement of the greater whole. What we want for our own lives is not what others want for theirs, despite the fact that the general character of these desires stem from the same species.

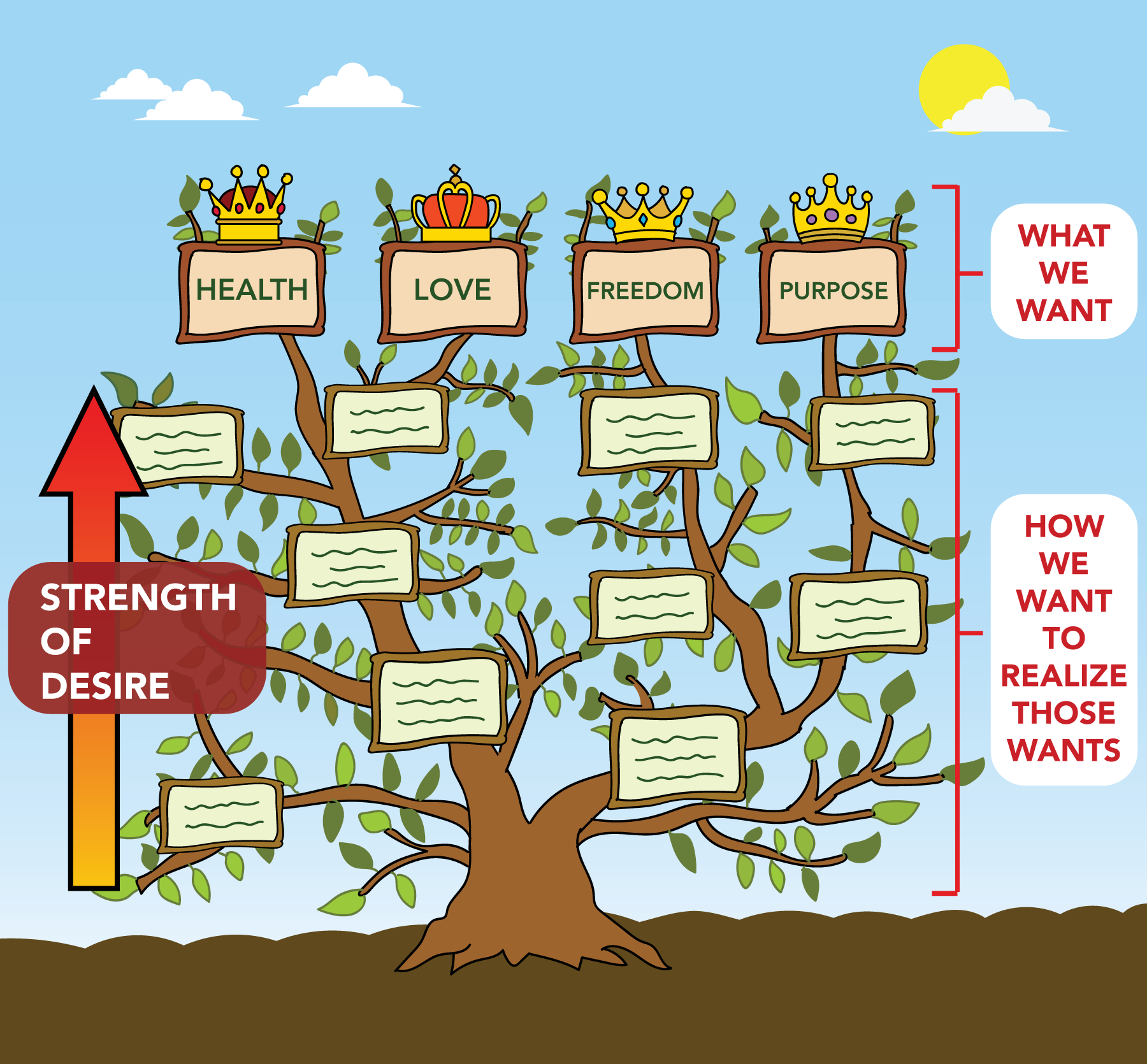

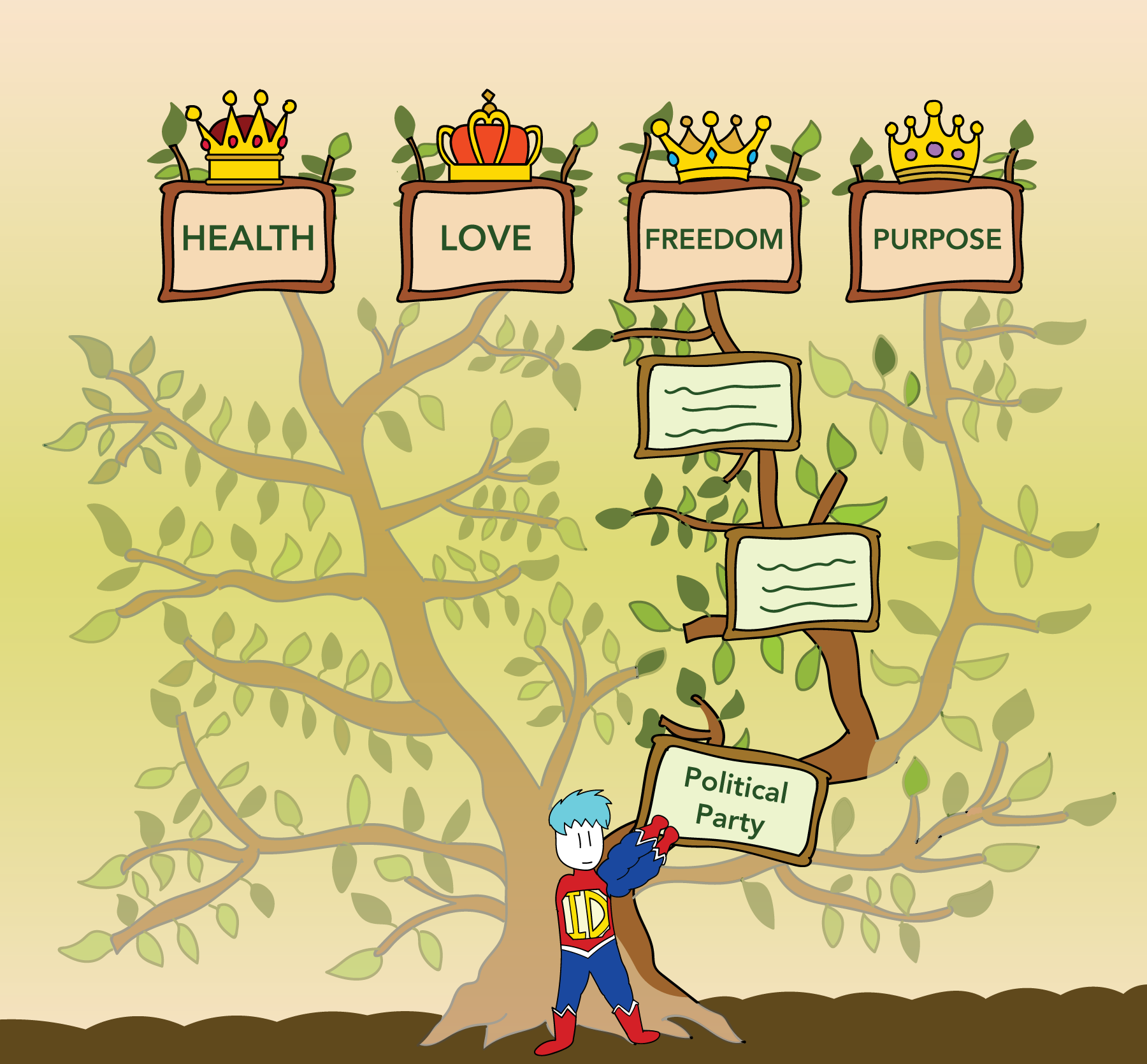

Everyone wants to be healthy, to (love and) be loved, to be free (through wealth or ideology), and to have a sense of purpose. These four things are the ancestral forebears in our family tree of desire, and every subsequent want is just a variant of these four predecessors.

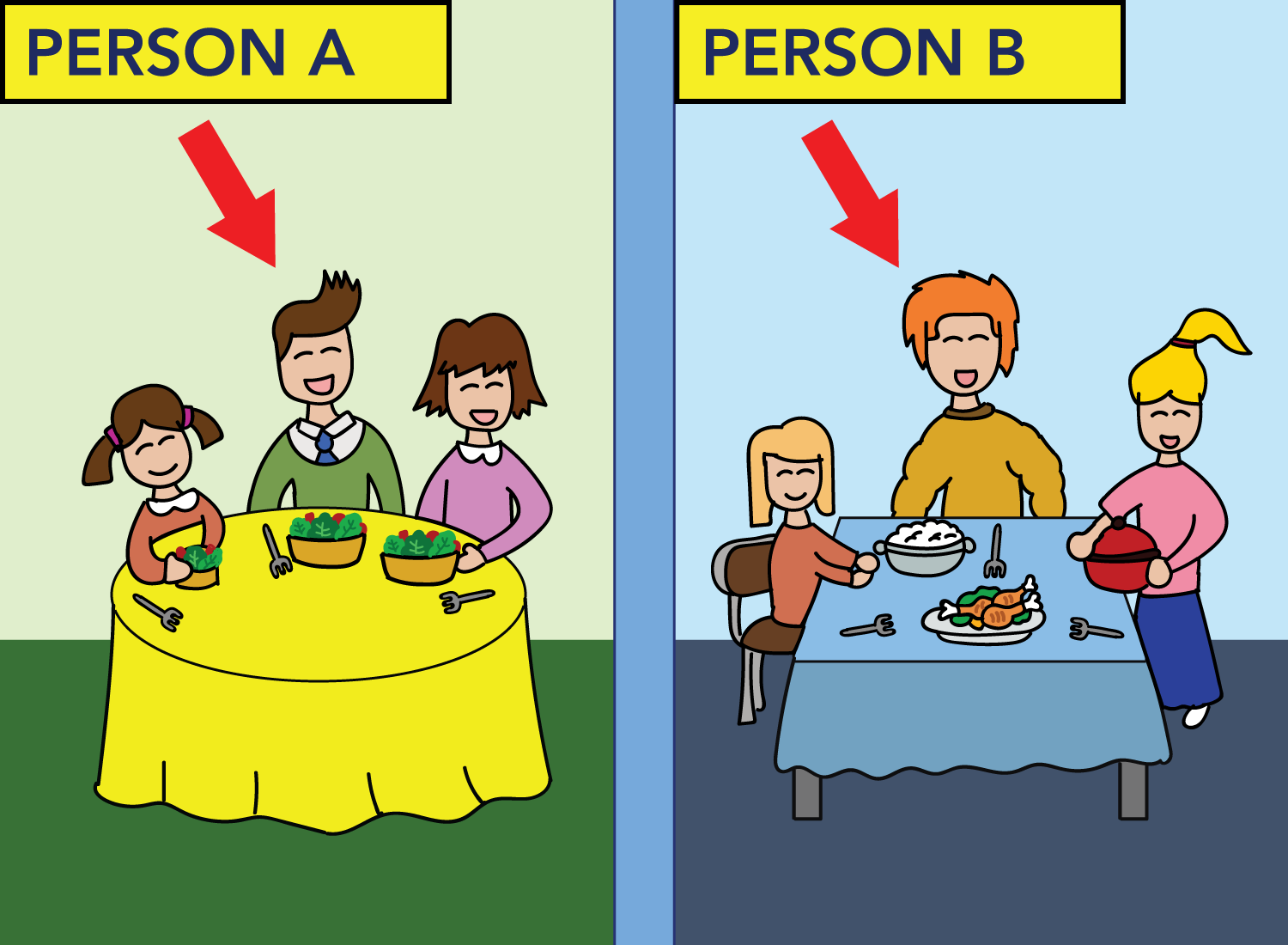

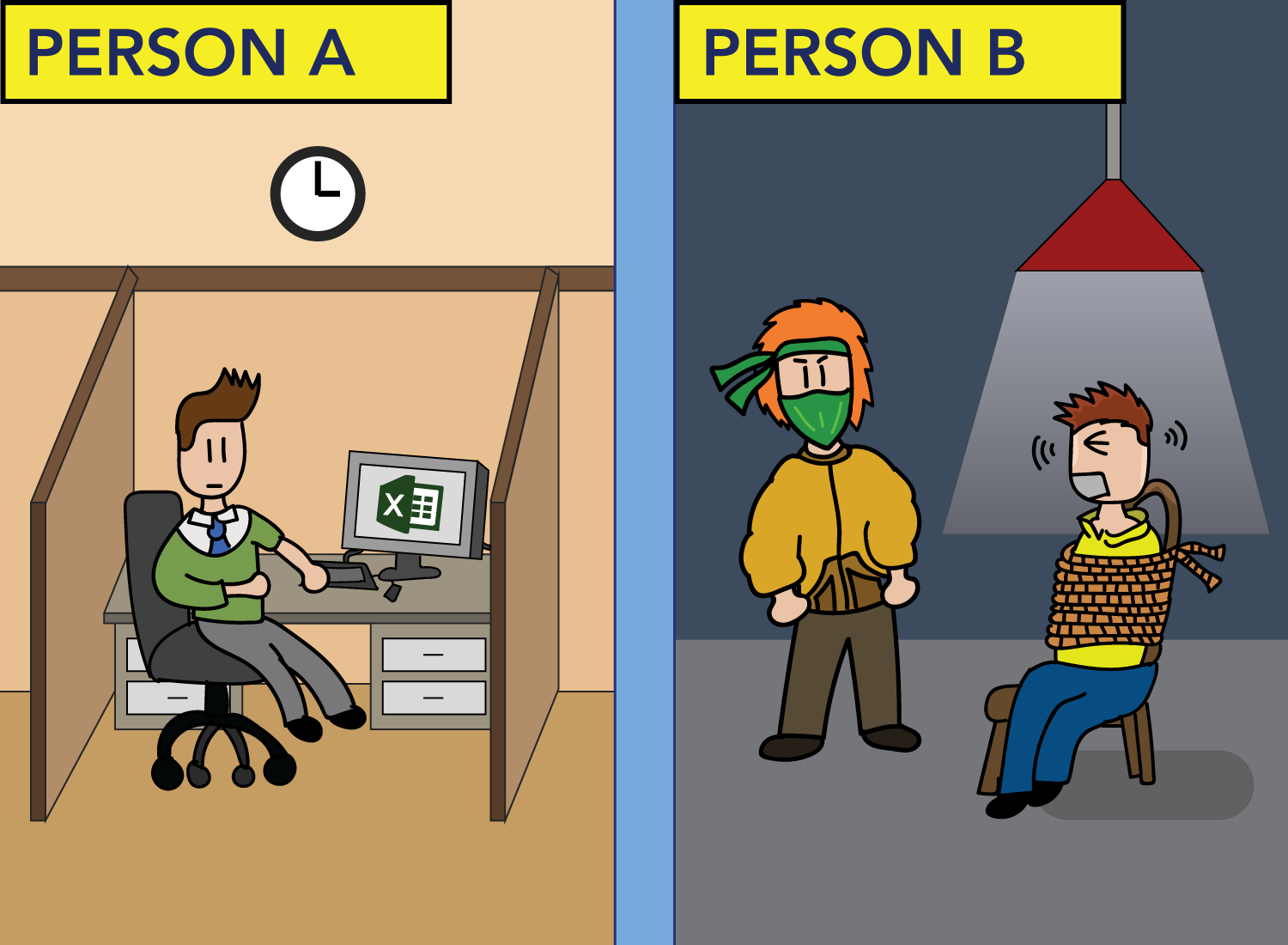

The misalignment between what you want and what another person wants is not in “what” you both want, but “how” you will get it. Person A and Person B both want to take care of their families, and on any given evening, their dinner tables will look very similar:

They both love their children dearly, and just want the best for them. But how they want to provide for their families can vary wildly. Person A might do it as a full-time employee for a reputable company, while Person B might do it as a member of an organized crime ring.

Both want the same things in life, but the pursuits they’ve chosen to get there put them in two separate lines.

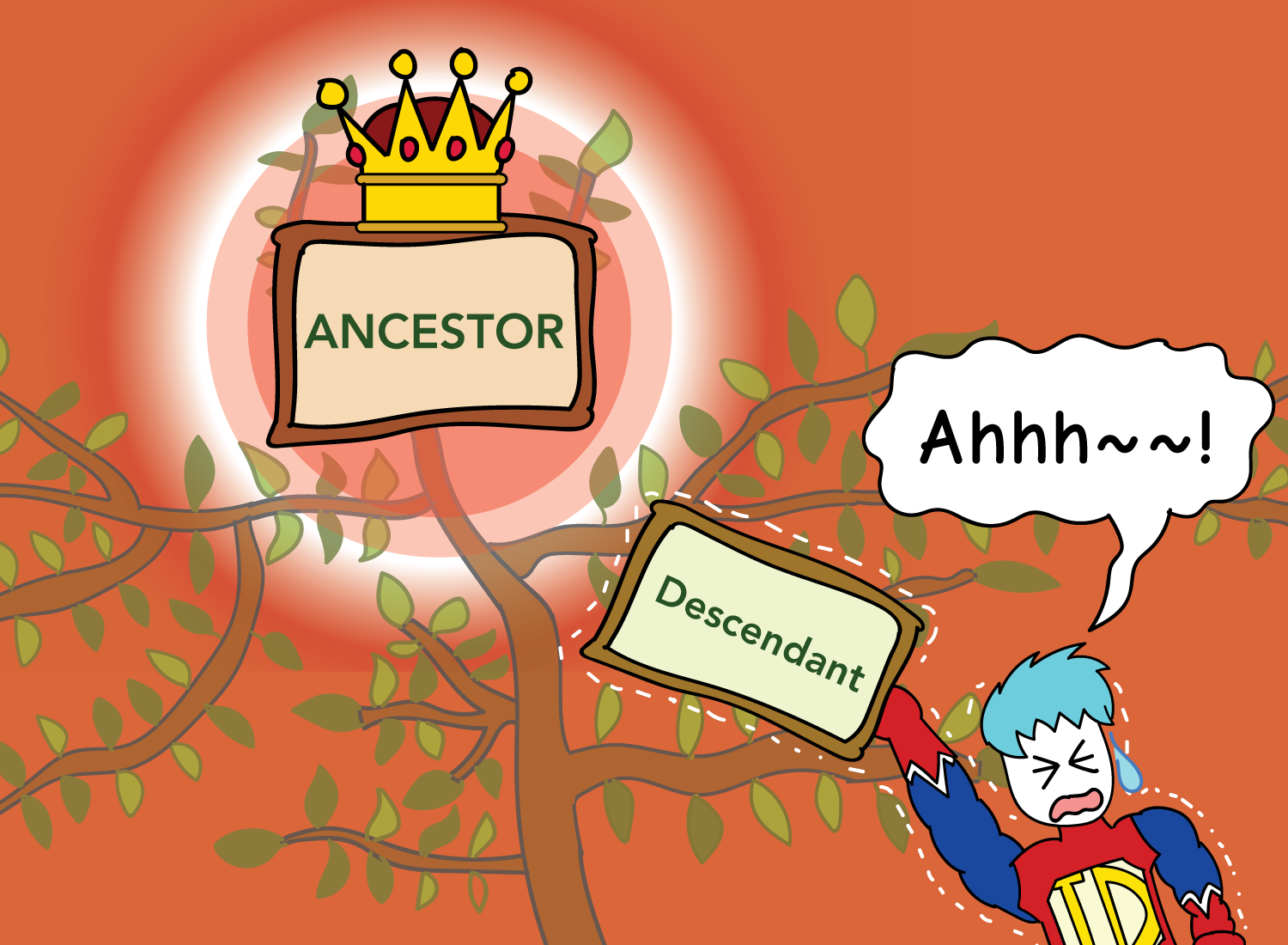

In the context of our family tree, the “how”s are the descendants of the “what”s. The DNA of the four ancestors (health, love, freedom, purpose) is imbued in every pursuit we embark upon, acting as the guiding force behind the reasons why we do what we do.

Why do we exercise and switch up our diets? For health.

Why do we spend so much time with our families and friends? For love.

Why do we invest in the stock market and vote for political candidates? For freedom.

Why do we search for meaningful work and attend religious services? For purpose.

Each pursuit is a descendant of one of these four ancestors, acting as mere representatives for what we as humans all want. However, there are some pursuits that carry more of that ancestral DNA in them than others.

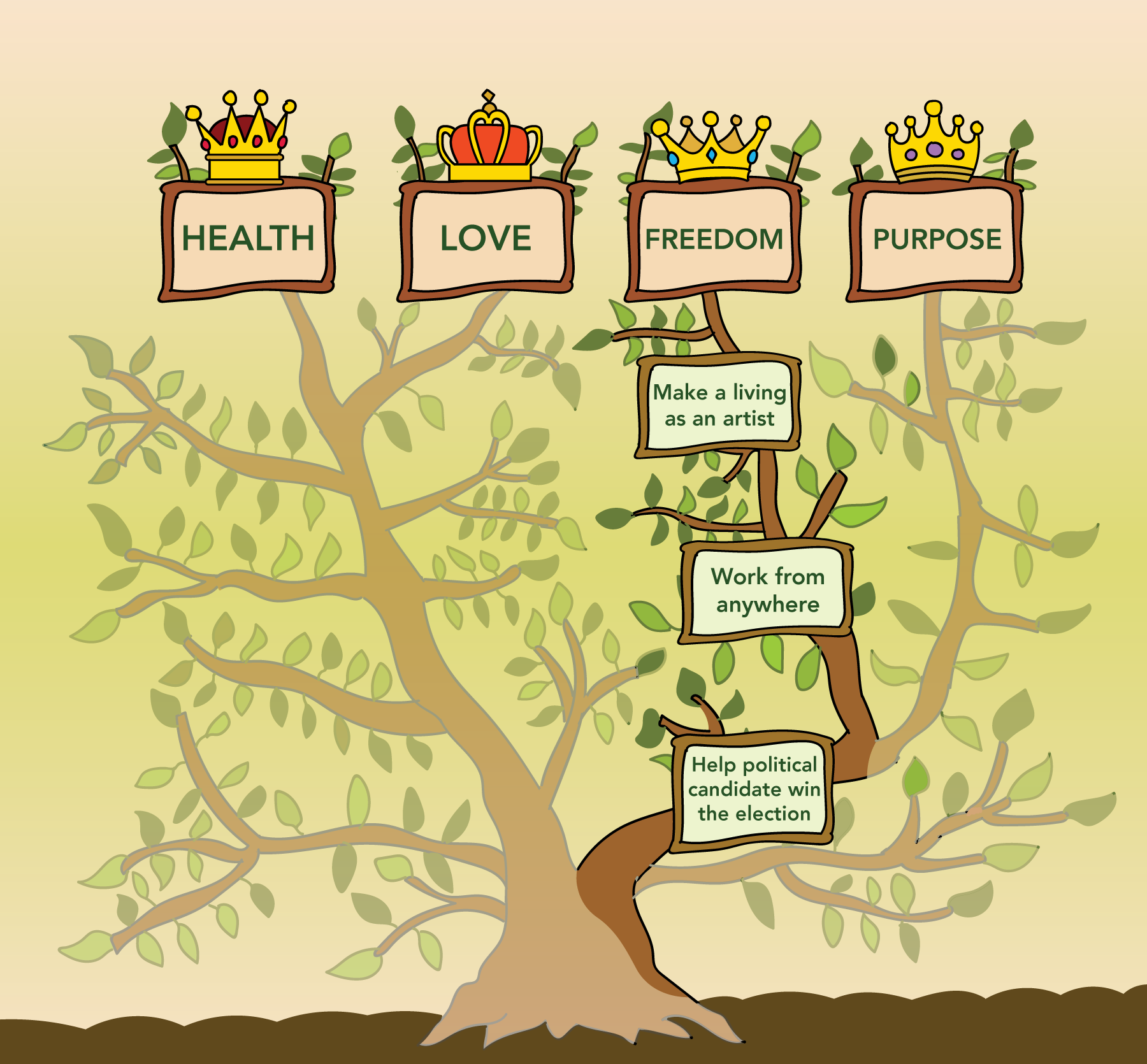

Consider the freedom lineage in this family tree:

You’ll notice that in this person’s tree, earning a living as an artist is much closer to the freedom ancestor than the desire to have his preferred candidate win the presidential election. Both are signals of freedom, but that DNA is much stronger in his desire for fiscal validation than the desire to see that one candidate’s face on TV for the next four years.

What this shows is that not all descendants are created equal. Some carry far less of their ancestors’ genetic makeup, making them weaker desires than the ones that are closer to the top.

The question of how we will realize our ancestral wants has been the greatest problem of humankind. We all have the same four ancestors, but the descendants that stem from them all differ. Humanity was given a game board with 7.5 billion players, but no one was told how the game should be played.

What does it mean to be healthy? To be loved? To be free? To have purpose?

Everything we care about resides in those questions, but we will never agree on the answers. It may be tempting to simply accept that conclusion and move on with life, but humans are not simple creatures.

One interesting trait that nature embedded in us is empathy, or the ability to share and experience someone’s emotional state as if it were your own. Whether you think empathy is a good or bad thing, it really doesn’t matter. It exists in all of us, and is arguably one of the greatest things that makes us human.

Empathy creates intimacy, even amongst people that you don’t know. It is so powerful that it can make you deeply emotional while watching a movie, despite knowing that you’re crying for a fake character that, in real life, is an actor with a glorious mansion overlooking the Hollywood Hills.

Empathy allows us to build deeper connections with those we know, and to feel for populations of people we’ve never met. This is why we can’t let each human run wild with how they want to realize their ancestral wants, because at some point, they will hurt another person, and empathy makes us feel that pain as if it were our own.

Empathy puts a check on bad descendants in someone’s family tree, and paves the way for the question of morality.

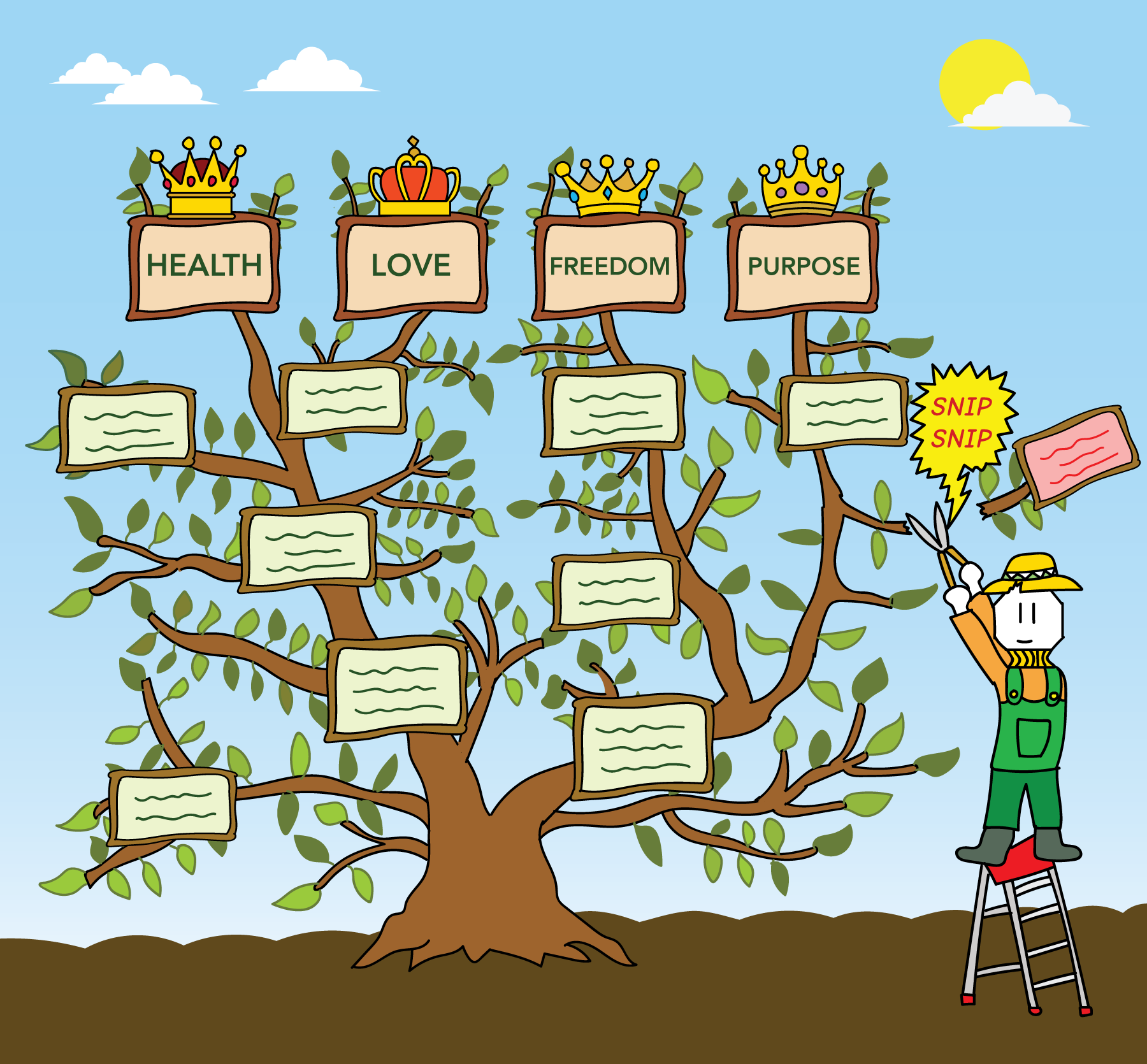

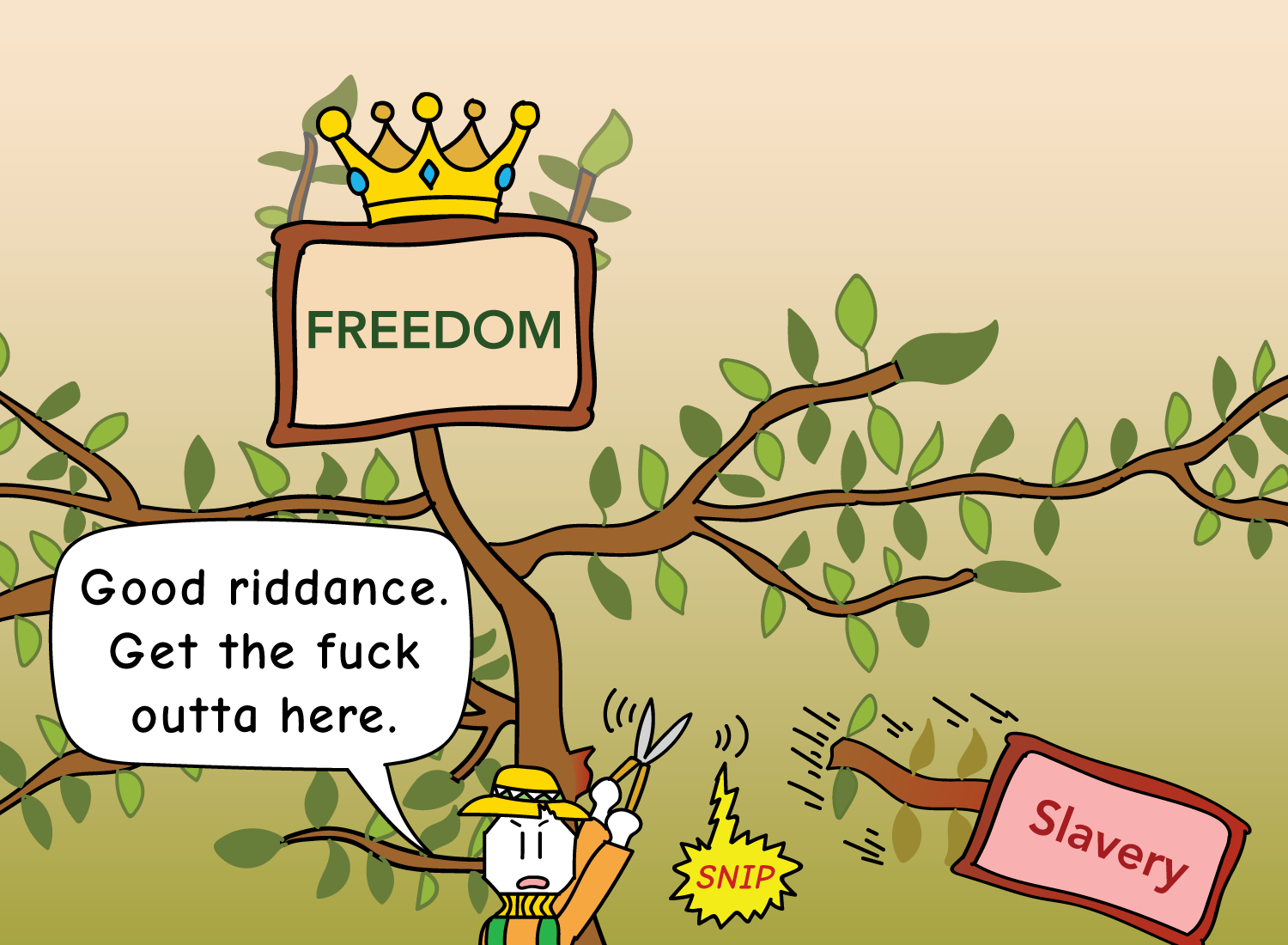

Morality is humanity’s quality assurance process. It asks whether each descendant is an accurate representation of an ancestral want, and if its realization would help or harm the well-being of others.

It is the gardener of our tree of wants, keeping it clean and cutting away the desires that no longer deserve to be there.

You might wonder why something as important as morality isn’t one of the four ancestral wants. Isn’t “being a good person” something that we all aspire to be?

Well, it would be something we desired if we didn’t all think we were good people to begin with. Remember, no one walks around thinking they are evil. It would be convenient if the most dangerous criminals in the world got together and called themselves “The Greatest Supervillains Ever,” but most of them probably think they’re doing the right thing for all the right reasons.

We desire things like freedom and purpose because we’re aware of when we might not have them. We can’t desire morality because we’re painfully unaware of when we’re being immoral. That responsibility generally falls on the shoulders of others, or society at large, to enforce.

Morality is a tricky thing for this very reason. Self-reflection can work in changing your stance on a moral position, but it’s nowhere near as effective as the thunderous voice of a crowd telling you that you’re wrong. The problem, however, is that the crowd takes forever to develop, so people could get away with doing shitty things for a long time before conventional wisdom tells them to knock it off.

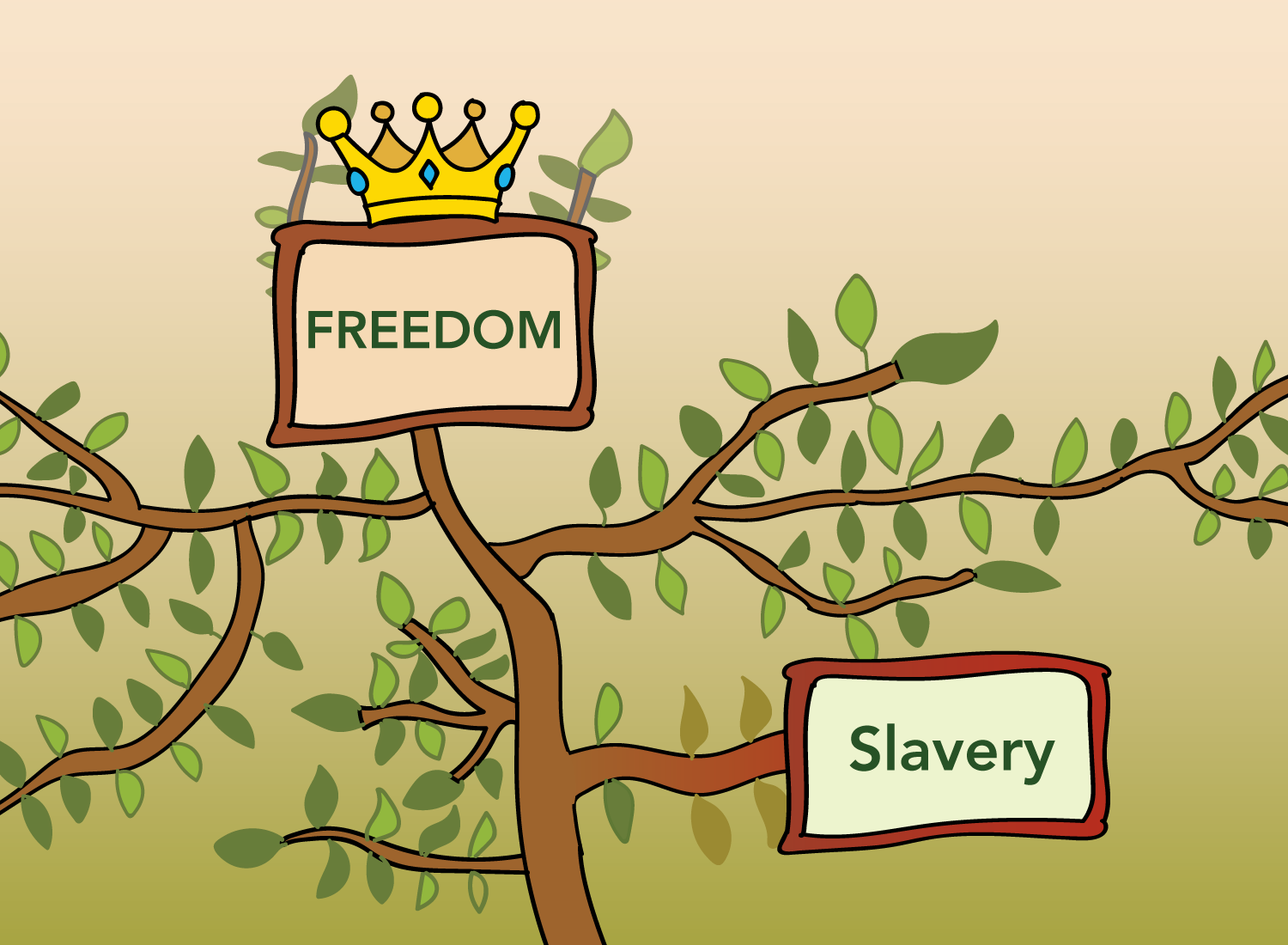

Let’s take the example of slavery to illustrate this.

We all view slavery as an evil and reprehensible thing now, but in the 1700s, that wasn’t the case. In the context of someone’s tree of wants at that time, slavery was a descendant of the (economic) freedom ancestor. It was viewed as a calculated business move that dramatically lowered production/labor costs, allowing for the fiscal prosperity of landowners.

This gaping moral blindspot is why some of the American founding fathers have legacies that will be tainted forever. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison did wonderful things for the future of the United States, but that will never change the fact that they owned slaves.

However, at the time, very few considered them to be moral monsters. Conventional wisdom baked slavery into the pie of capitalism, and it was seen as a necessary ingredient of the national economy. It became so essential to the operation of the American system that morality skimmed over it, conveniently ignoring the inhumanity of the practice as long as profits came pouring in.

Morality takes a lot of movement and time to update its software, and slavery was one of the cases where it got complacent for too long. Although it was eventually purged from the collective tree of desires, its extended allowance as a descendant caused suffering for a needlessly long period of time.

One of the greatest sources of human suffering come from the allowance of bad descendants. Inhumane practices in the name of religious liberation. Voter suppression in the name of political gain. Worker abuse in the name of corporate profit.

Morality may be slow to act as a whole society, but it can be quick for the self-reflective mind. Start with your own family tree. Which of your descendants bring about needless suffering for others, but may have escaped your moral surveillance? Are there certain desires you have that benefit your goals, but take away from the well-being of others? What about things that seem fine now, but you think will be chastised as an evil in the near future?1

Instead of convincing others to change their moral position on something (chances are you won’t get remotely close), take a good look at your own tree of wants, and study the character of your desires. If you structure them so they embody a genuine compassion for yourself and others, then that will speak louder than any words of persuasion you try to use at the dinner table.

Morality is the tool you can use to determine whether or not a descendant should exist. Let’s say that upon reflection, you decide that it is worthy of staying. Then the next question becomes: How close to the ancestor should it be? Or in other words: How do I determine its placement in the tree of wants?

We all have certain desires that are stronger than others, so they will map themselves out in accordance with our preferences. The key thing that determines these preferences, however, comes down to one thing: our identities.

Our wants are indicative of the identity we embody. If you identify as an artist, you will have a strong desire to work every day on your craft. This will place it as a very close descendant to the purpose ancestor.

If you identify as a marathon runner, daily exercise will be positioned close to the health ancestor. If you identify as a mother, the desire to spend precious time with your kids will be high up there in the love lineage.

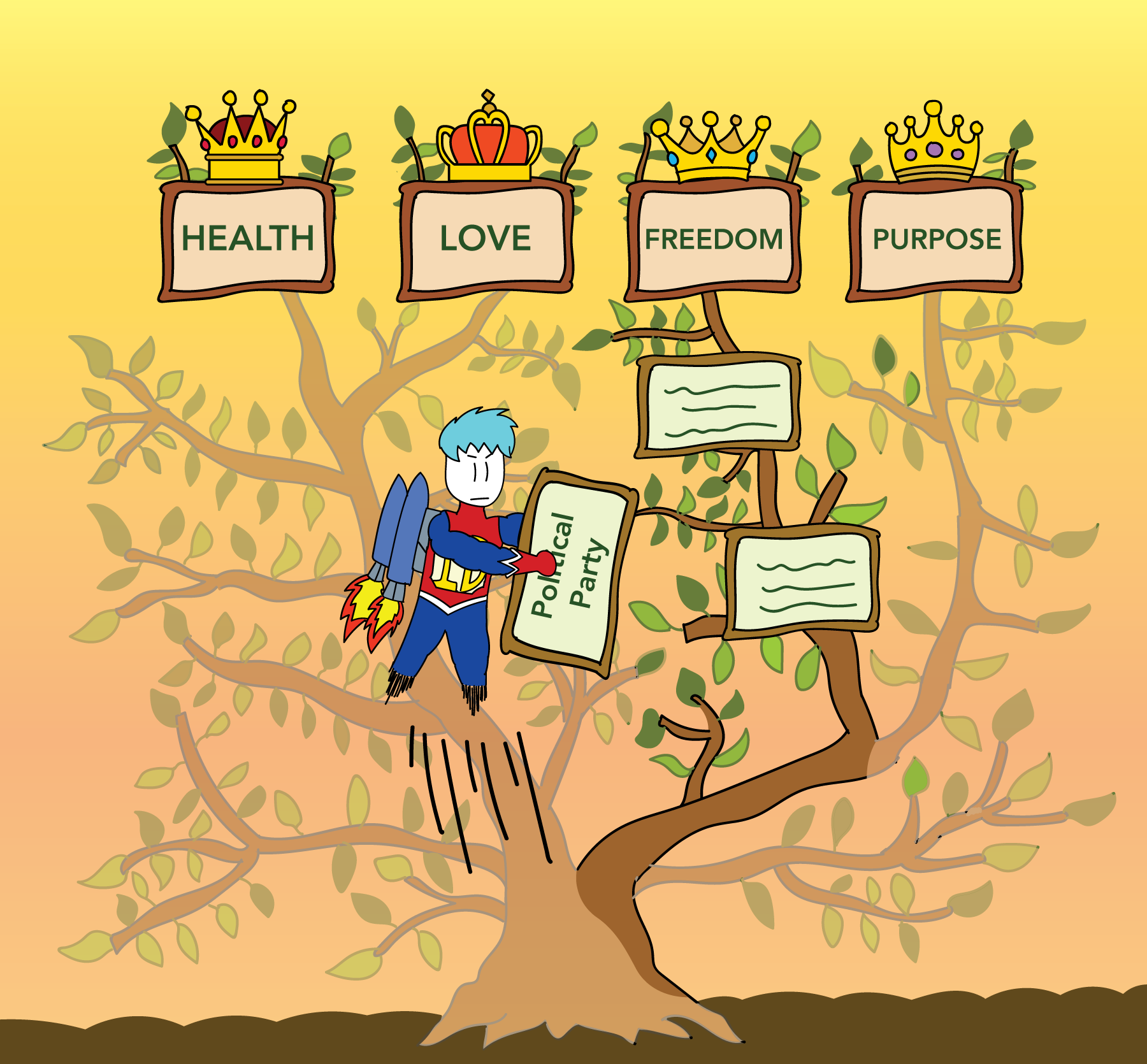

Your identity determines the rank-order of your desires, but since the things you identify with change over time, so does the structure of your tree. Descendants can either be demoted down the tree, or they can grow stronger and move up.

It’s this latter situation where things can get tenuous.

The closer our desires get to our ancestors, the more consuming they become. The closest ones become our chief desires, which govern what we do in our day-to-day lives. Attachment becomes inevitable, and our ability to fulfill them determines how happy we feel about the direction of life.

Chief desires, however, are still manageable. We’re able to understand that they are mere representatives of the greater ancestral wants that sit above them. We may work hard to get that promotion, but can understand that it’s just one of many ways to feel validation. We may feel emotionally invested in a partner, but can keep in mind that love shouldn’t be isolated to this one person.

Chief desires are just stronger manifestations of the four ancestors of health, love, freedom, and purpose. As long as we can clearly categorize them as descendants, we can still zoom out and see the greater picture.

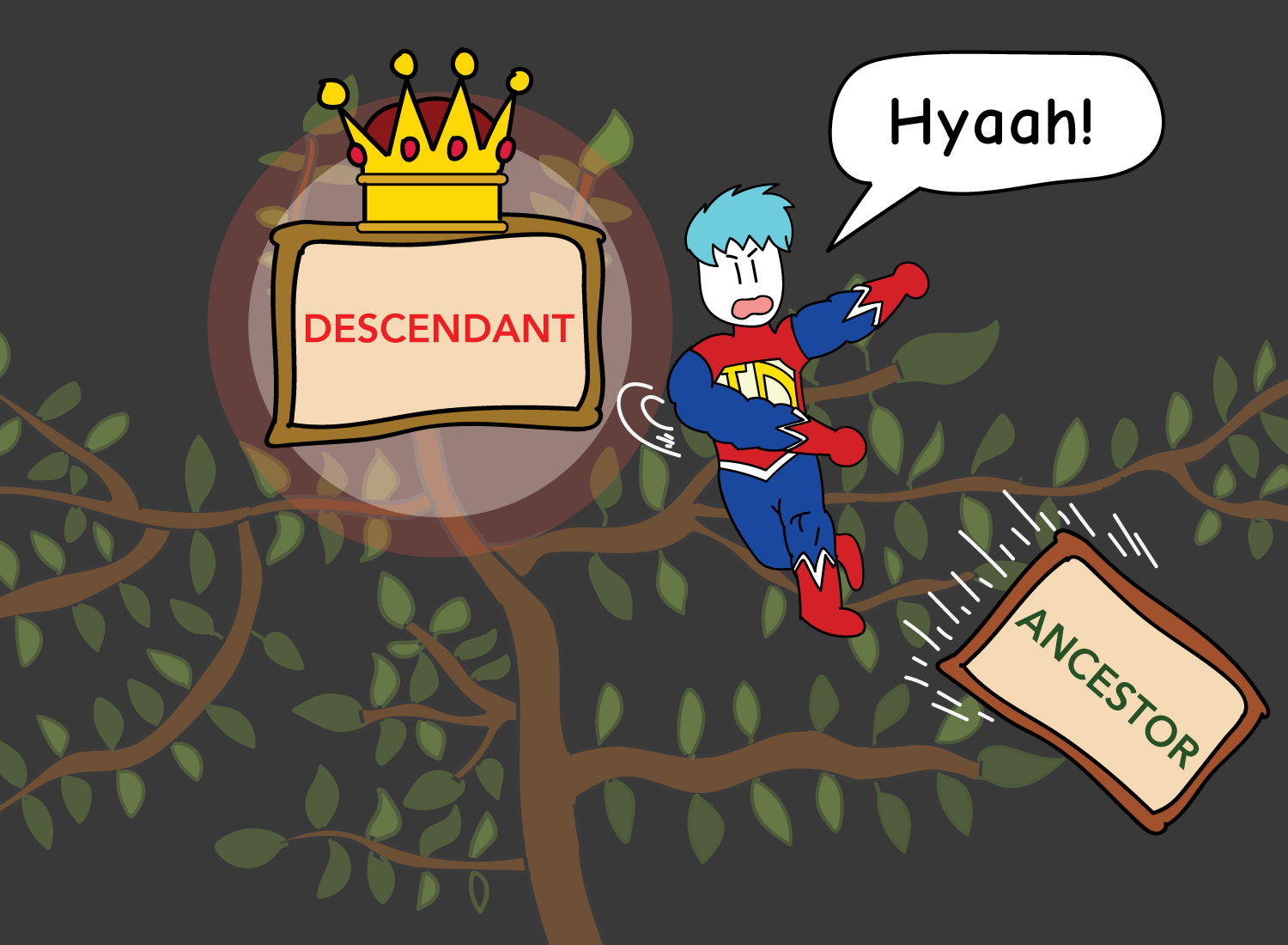

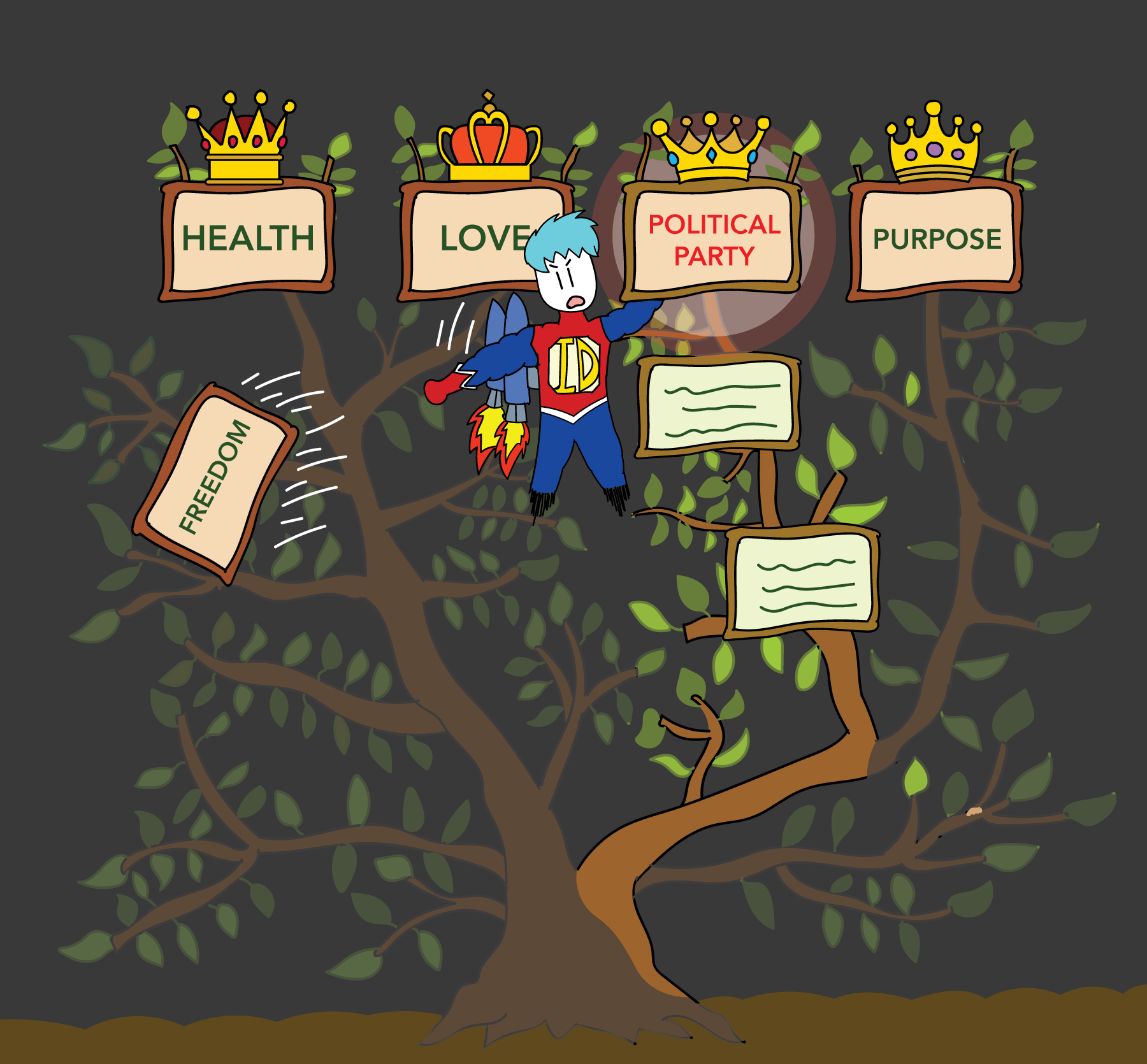

The problems emerge, however, when we can no longer make this distinction. Sometimes our desires grow so powerful that we forget they are a means to an end, and not the end itself. The descendant overthrows the ancestor, and takes its place amongst one of the four coveted spots.

When this happens, you forget that all humans ultimately want the same four things. Instead, you segregate the world into those that want this new ancestor as an end goal, and those who don’t. You are the one with the real answers, while everyone else is clueless.

This happens in all kinds of situations, but politics is a space where it happens regularly.

At its core, a political opinion is nothing more than an expression of freedom. The political party/candidate you align yourself with is a crude signal of your values, and expressing your preferences is a way to exercise your ideological leanings. The desire to have your political party prevail is simply a descendant of your freedom ancestor, as that will create a country where you feel free to be who you want to be.

Tribalism, however, is a whirlwind that can suck you into rabid fanaticism. It’s easy to get swept up by the feeling of “us,” and even easier to push away those that belong to “them.” As I mentioned earlier, identity is the crucial thing that determines the placement of certain desires, and infusing tribalism into them catapults their position in the tree of wants.

When this happens, nuance is removed from the conversation. Instead of evaluating each independent issue objectively, tribal belief systems group them all together, stamp them with a “party-approved” judgment, and distribute these templates out to each of its members.

For example, what the hell do issues like gun control, abortion, and taxation have in common? Pretty much nothing, but tell me what political party you’re affiliated with, and I have a very good shot at guessing what your stance is on each of those issues. That’s tribalism at its finest. Remove nuance, add predictability. Rinse and repeat.

When you condition yourself into this mode of thinking, you forget that political opinion is merely a crude representative of free expression. Instead, you believe that your political affiliations are the final embodiment of freedom itself, making it the overarching want for everything along that lineage.

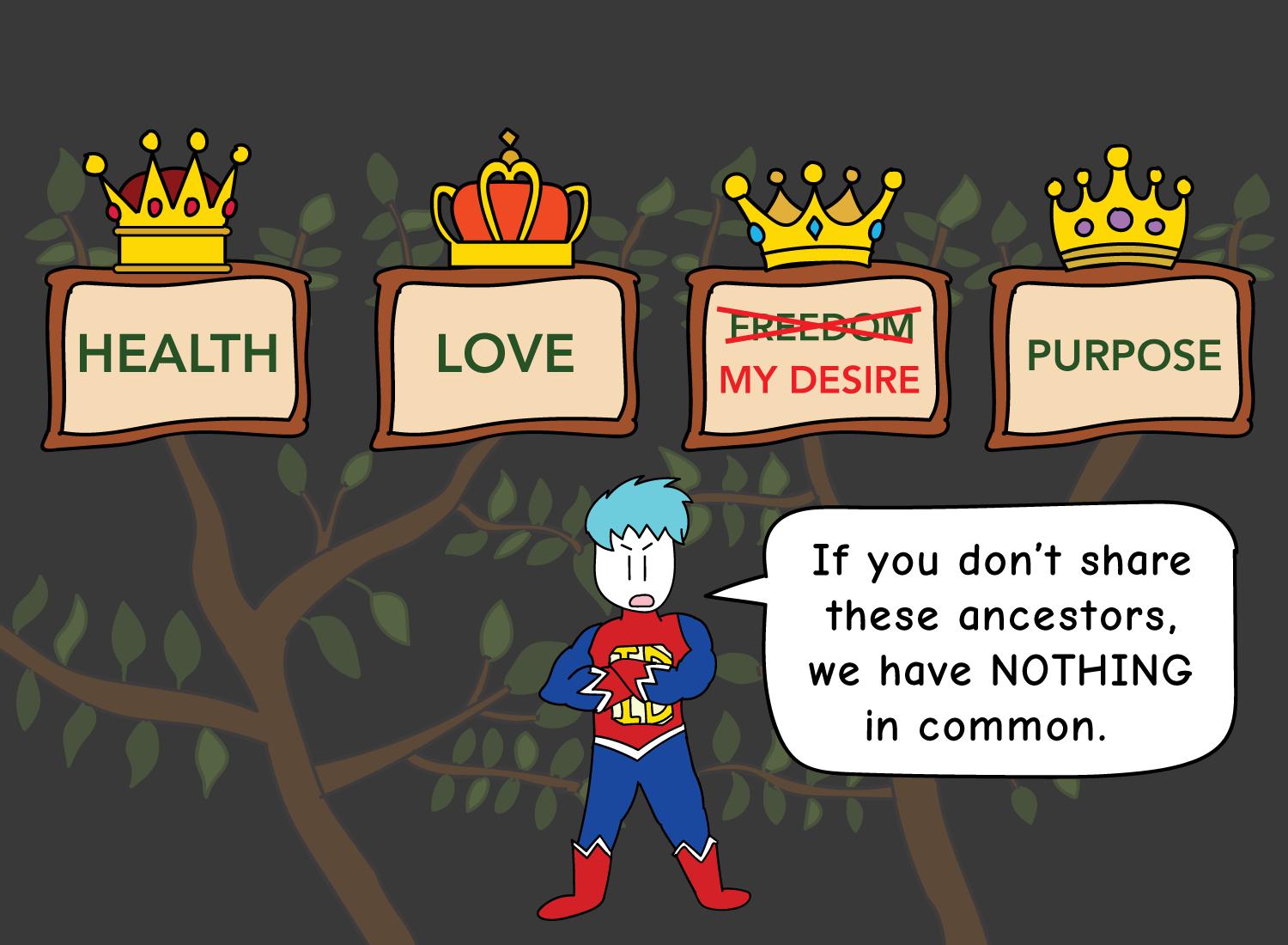

When the makeup of your ancestors changes in this way, you lose your shared humanity with others. You forget that everyone else has very similar wants and needs as you. We all desire freedom, but you think that your views are the only viable embodiment of it, so any voice of argument indicates a hatred for what you believe is right.

This leads to something dangerous: the dehumanization of others. Dehumanization reduces people into beings that look or seem nothing like you. Your enemies are perceived as terrible people, doing terrible things and indoctrinating their children with ill-conceived beliefs.

But of course, nothing is further from the truth.

If everyone in the world had the chance to spend one full evening at the home of someone they hated, so many of our conflicts would resolve themselves. They would realize that their enemies love their children and partners deeply, just like they do. They would hear their enemies offer up prayers of good health and peace, just like they do. They would experience the feelings of unity that astronauts get when they observe Earth from space, but within the four walls of their enemy’s home.

We all share the common ancestral wants of health, love, freedom, and purpose. But when we replace one of these crucial elements with an excess desire, we lose sight of the shared journey we are all undertaking together.

You may find a sense of purpose in your work, but what happens when you make work the entire source of meaning in life? You would look down on your friends and family, seeing them as obstacles that get in the way of achieving your dreams.

You may want the respect and adulation of others, but what happens when you replace love with the desire for social approval? You would reduce someone’s entire identity to an incremental increase in your follower count, viewing them as nothing more than a validation of your ego.

Is this the kind of society you want to live in? One where we forget that we all fundamentally want the same things? One where we fail to realize that we have much more in common than a first impression may give?

I don’t. I want to live in a place where we understand that we’re all looking at the same family tree of wants, with each lineage stemming from the four ancestral elements we all share.

The question of how we can ethically move up each lineage is a difficult one, but we do have something that’s trying to figure it out. Our gardener of morality is working hard every day, removing the parts of the tree that don’t deserve to be there. Setting a universal standard on how we will ethically realize our wants sounds far-fetched, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

As for the structure of the tree itself, its contents will vary from person to person, but remember that we are all moving toward the same ancestral wants. Instead of focusing on the small percentage of things that separate us, let’s embrace the collective journey we’re all on together, engaging in conversation and smoothing out the differences that cloud access to that shared insight.

Now if that sounds too hard, then we have to do better. On the other side of dialogue is violence, and that’s a wildfire that wants nothing more than to burn the entire tree down.

I want to live in a society where discourse solves more problems than hatred. The first step involves self-reflection: I must aspire to look at my own tree, study its contents, and ensure that no individual desire fogs up the reality of our shared humanity.

The next step is to convince you to do the same.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts: