The Economics of Writing (And Why Now Is the Best Time to Do It)

I’m a bit sheepish when it comes to writing about writing. There’s so much that’s already been said about the topic, and once you remove all the bells and whistles, all advice on writing comes down to one main point:

To be a writer, you have to consistently show up and write.

That’s all it really comes down to – nothing more, nothing less. The rest of the advice that is packaged through ebooks, blog posts, and mailing lists is about setting up productivity schedules, beating procrastination, and overcoming doubt to ensure that you show up everyday. While there’s value in that type of advice, I find that most of these writing-about-writing folks are saying the same thing over and over again.

In a field so crowded, one would think that there’s nothing more to add here. However, one recurring theme on this blog is to zoom out and try to understand what is happening underneath the hood of today’s conventions and norms. When many people are championing variations of the same idea, it’s important to ask why they think that, and how that idea came to be in the first place. Without asking these questions, you are prone to getting swept up by the mob, blindly trusting the wisdom of the herd without developing your own intuitions.

The questions of “why” and “how” will drive this post as we explore the mechanics of the show-up-everyday-to-write narrative. What about today’s landscape makes consistent writing so promising, how can this translate to a career for a writer, and why is now the best time to do it?

A good place to start would be the most well-known essay on the topic of content creation in the internet era, Kevin Kelly’s 1,000 True Fans.

An Overlooked Insight of 1,000 True Fans

If you’re a content creator of any kind, you have likely read (or heard of) the thesis behind the 1,000 True Fans essay. The common takeaways come down to these two points:

(1) In order to earn a living as a creator, you don’t need millions of fans. You just need 1,000 true fans that will pay you $100 a year (which amounts to $100,000 a year – a comfortable living). Having someone pay you $100 a year may sound like a lot, but a “true fan” will buy anything you put out.

(2) You must have a direct relationship with your fans, keeping all of their support. There’s no intermediary between you and the fan taking sizable chunks of money; no publisher, music label, studio, retailer, etc. This type of direct support has been made possible by the internet.

Kelly’s message is both informative and hopeful. The number one concern creators have is how they can earn a living doing what they love, and Kelly offers an answer that feels attainable. If you can thrive in a small, original niche, you may not be a millionaire, but you can certainly have a sustainable career.

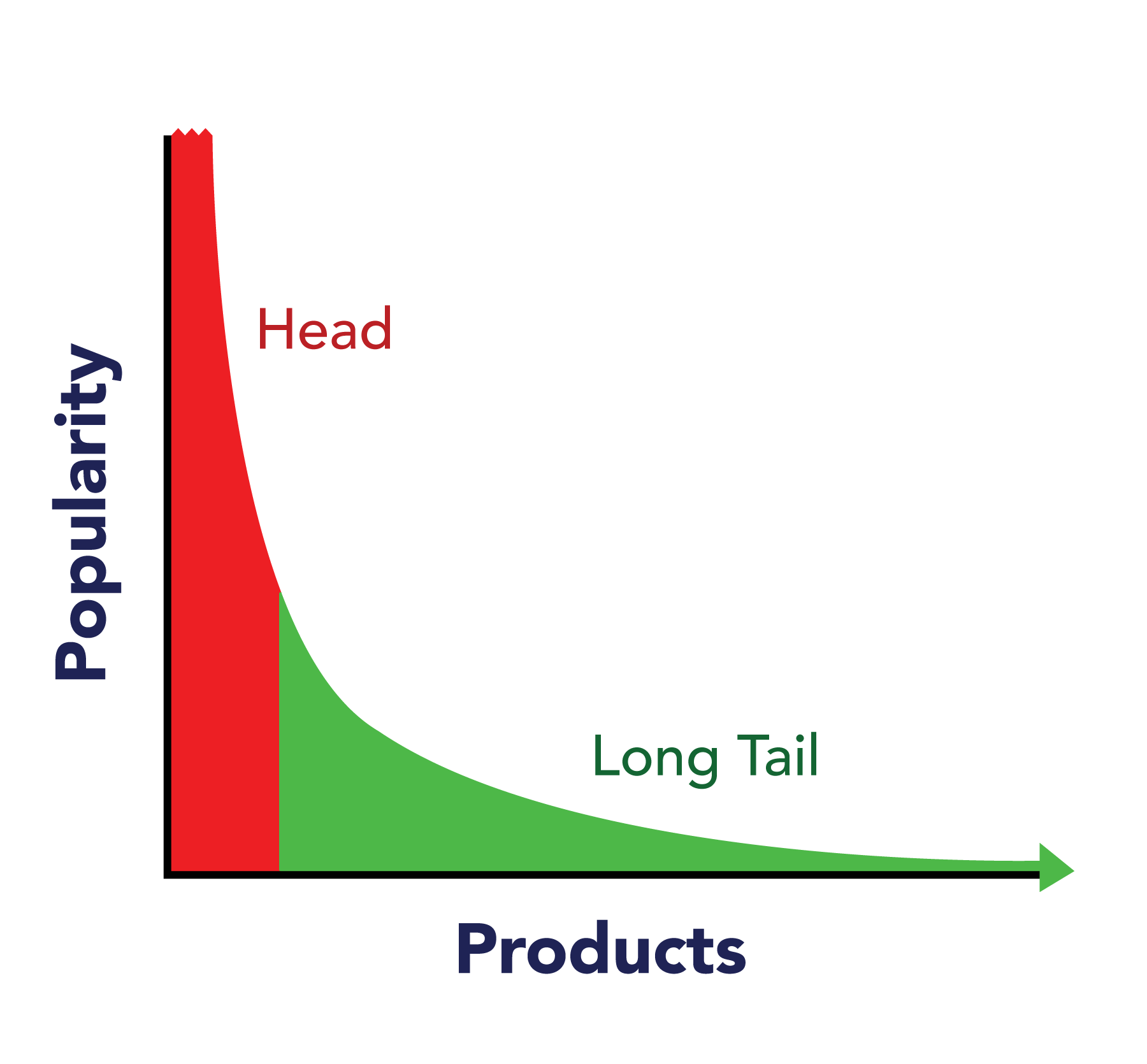

The power of the small is illustrated in the concept of “The Long Tail,” where the total sum of all the lesser-known, obscure products is just as large as the total sum of all the very popular, best-selling products. In other words, the area of the green section is equal to the area of the red section:

Prior to the internet, being in the red section was the only way to make good money as a creator. You needed the proper intermediaries to reach a critical mass of people, and it was only through the sheer volume of fans that a decent return was possible. However, in today’s digital era, this landscape has fundamentally shifted.

This is where the most interesting yet overlooked part of Kelly’s essay shows up. It appears only in his revised version (emphasis mine):

This new ability for the creator to retain the full price is revolutionary, but a second technological innovation amplifies that power further. A fundamental virtue of a peer-to-peer network (like the web) is that the most obscure node is only one click away from the most popular node. In other words the most obscure under-selling book, song, or idea, is only one click away from the best selling book, song or idea.”

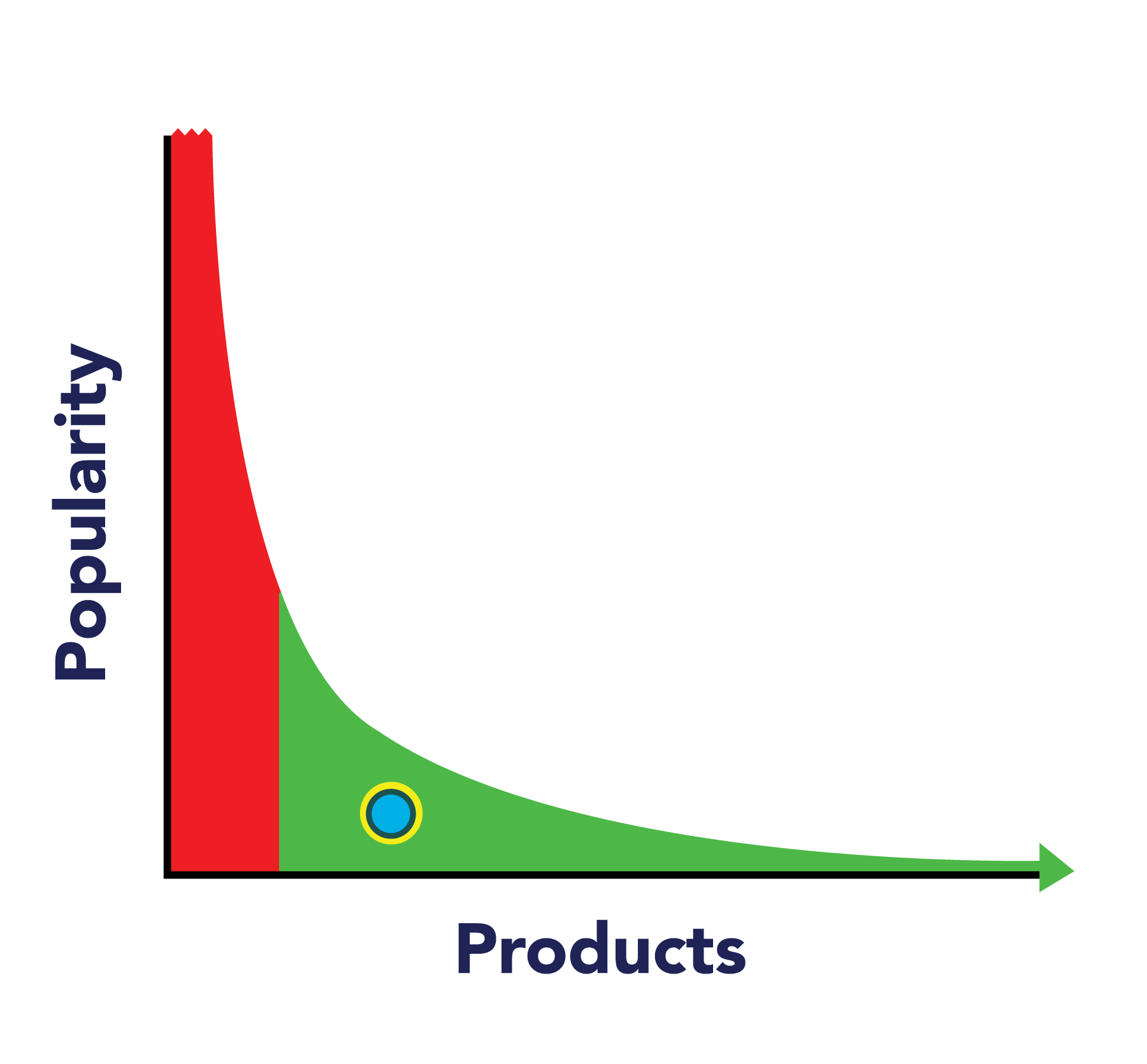

Essentially, going from here…

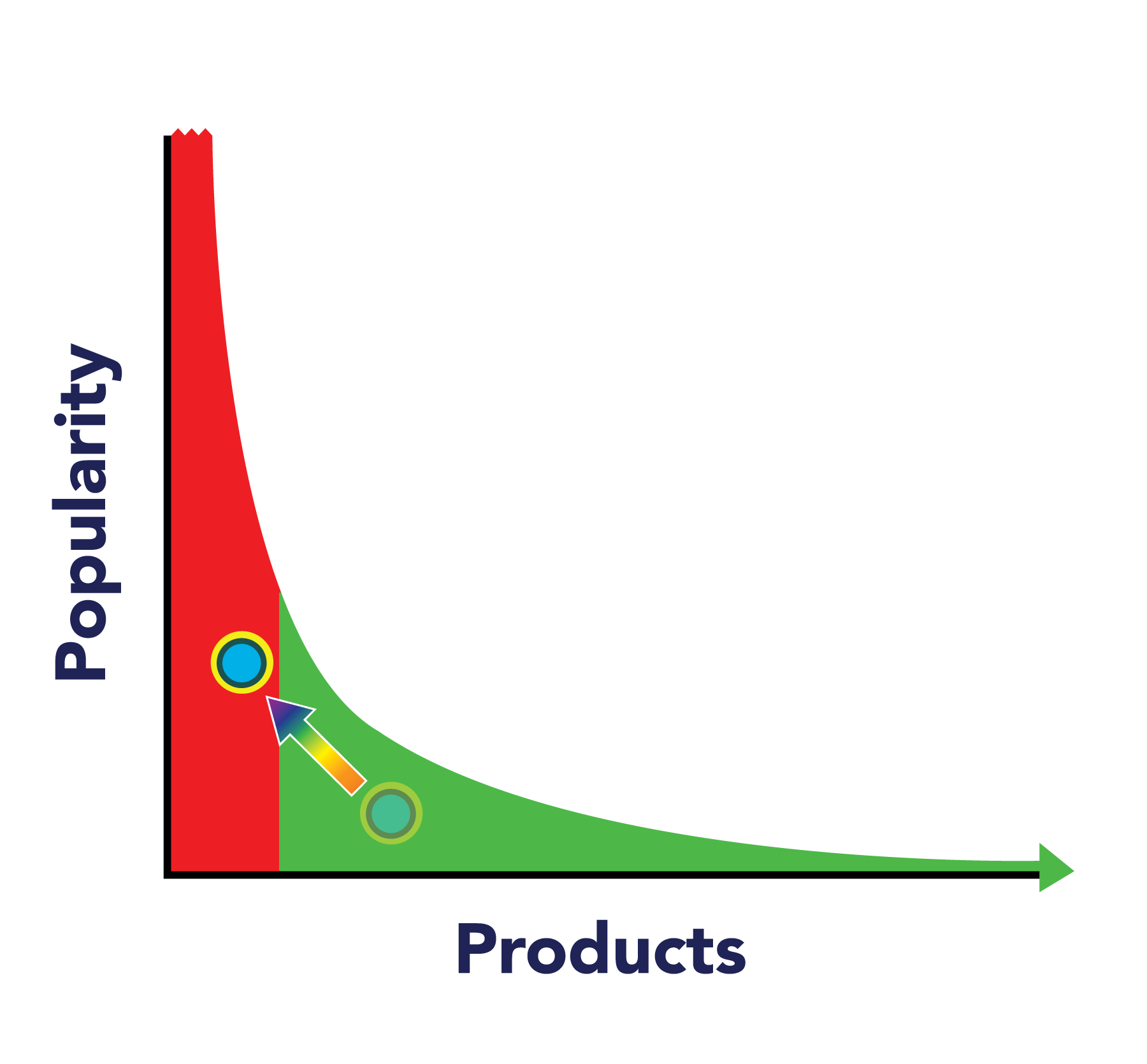

…to here…

…can happen instantaneously.

This may seem like common sense today, given that things “go viral” all the time. The takeaway here, however, is not to aim for viral content, but to understand why this type of move is even possible. The two mechanisms that allow for an obscure node to be one click away from a popular one are especially interesting when it comes to text, and illustrates why there’s no better time than now to be a writer.

Mechanism #1: The marginal cost of creating and reproducing your work is zero.

If you were a writer in the pre-PC or pre-internet era (aka most of human history), your words needed to be distributed via a tangible canvas. Paper was the dominant medium here, meaning that printing and distributing your work was pretty expensive. Not only did it require significant upfront costs to start (printing equipment, shipping logistics, staff salaries), the additional costs required to serve an additional reader were also high (more raw materials, more shipping costs, etc.).

In economics, the costs required to produce or serve an additional user are called marginal costs. In the pre-internet era, having more readers meant that you needed more magazines, newspapers, or books to print and distribute. Where your readers were located mattered greatly; serving a reader in a faraway city vs. someone in your city of residence could amount to a 2-3x difference in marginal costs.

This meant that the amount of readers I could reach was constrained by the supply of product I could afford to make. There could be 10,000 people across the world interested in reading my work, but if I only had 100 books on hand, 9,901 of them wouldn’t have access to my stuff.

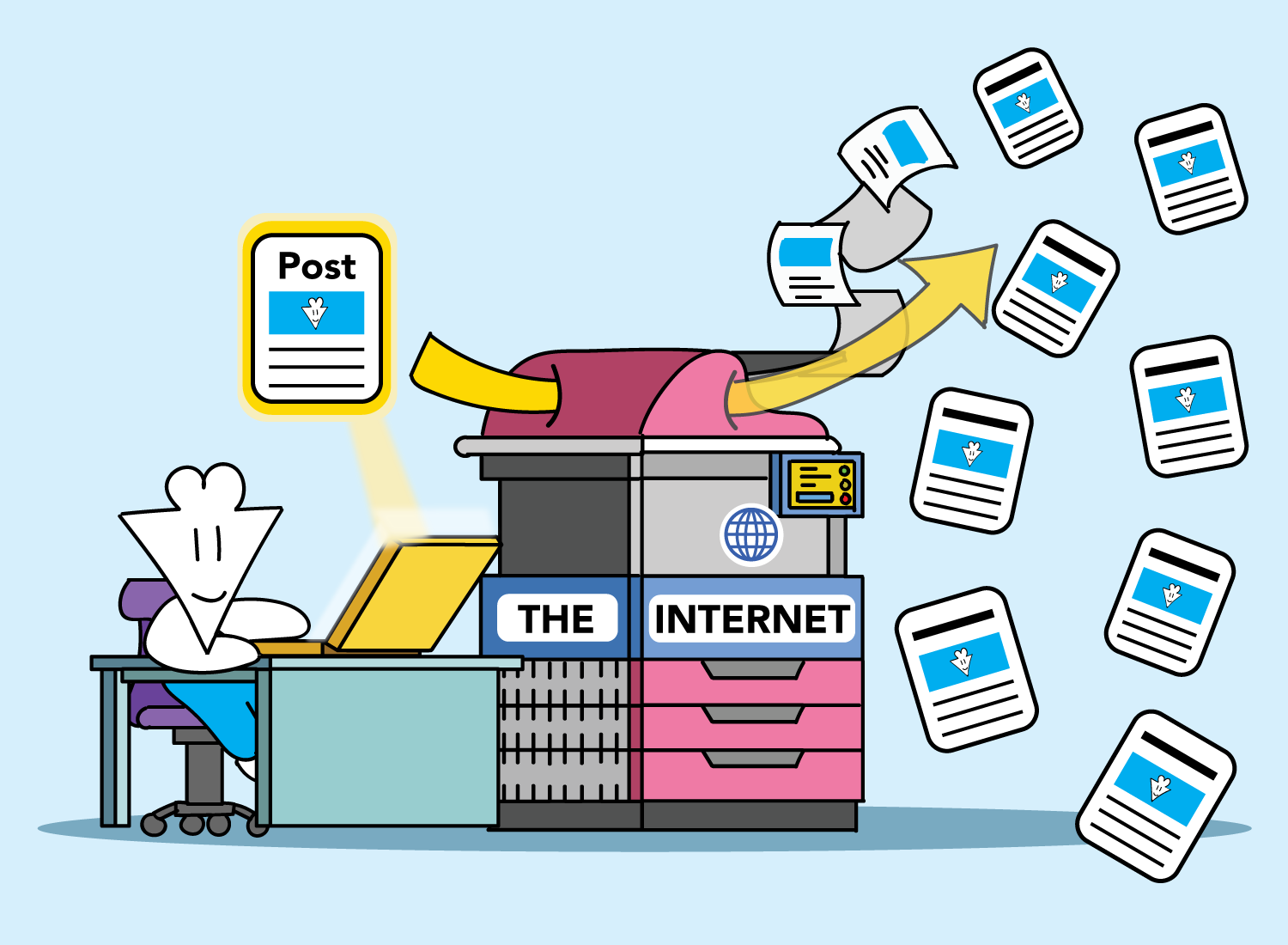

This type of supply restriction is no longer the case with the internet. The internet has digitized media, and of all mediums, text is the easiest (and cheapest) to produce and replicate infinitely.

With the exception of some small server expenses, there will be no difference if something I write reaches 10 readers, 10,000, or 100,000. Obscure works are just one click away from the popular ones because of this; the moment my work is shared, it has the potential to reach a significantly broader audience for free. Demand, not supply, is what makes my work accessible, and the fact that my work can be infinitely replicated means that its reach is exponential.

Zero marginal costs are a huge deal, and are one of the fundamental reasons why the internet has changed media. Music has now moved to the streaming model as a result of it, and video has moved from TV to platforms like YouTube and Netflix, where the content can be shared and viewed at any time.

But text is different in that it is essentially free to create, host, and distribute. Music is still largely controlled by labels, and video is still pretty expensive to create and host. As a writer though, you can create a post, publish it, and send it out to your readers at no real cost to you. And thanks to zero marginal costs, the amount of work you put in will be the same, whether your post reaches 100 people or 100,000.

So this then begs the question… if you’re able to publish and distribute everything yourself, how much value does the traditional publisher add in all of this?

Well, as it turns out, not much.

Mechanism #2: The traditional publishers, or the gatekeepers of writing, are no longer necessary.

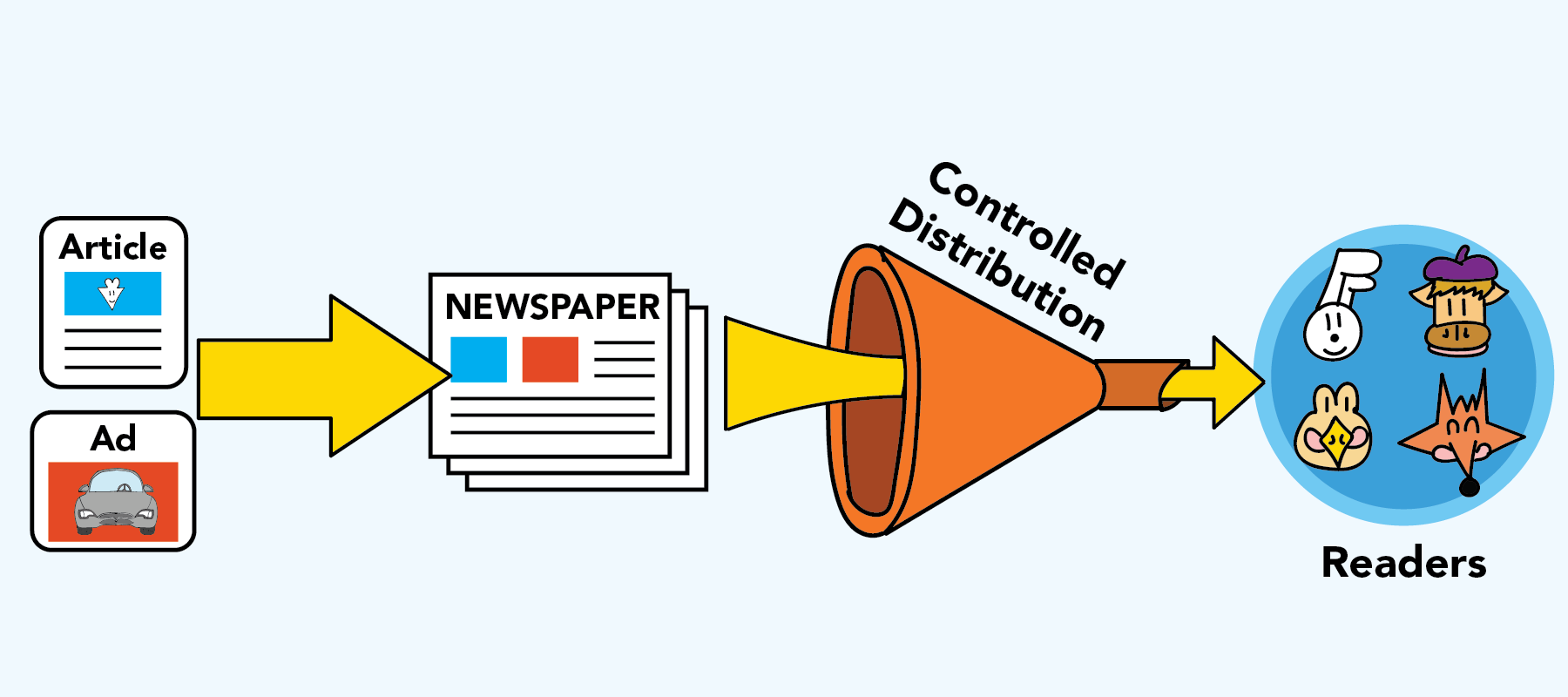

Prior to the internet, spreading written ideas was expensive. Marginal costs were high, so writers needed publishers (the New York Times, Newsweek, Time Magazine, etc.) to put up that capital for printing and distributing their work. Of course, publishers needed to make money too, so they would bundle their writers’ articles with paid advertisements into a newspaper or magazine, which would then be sold to readers:

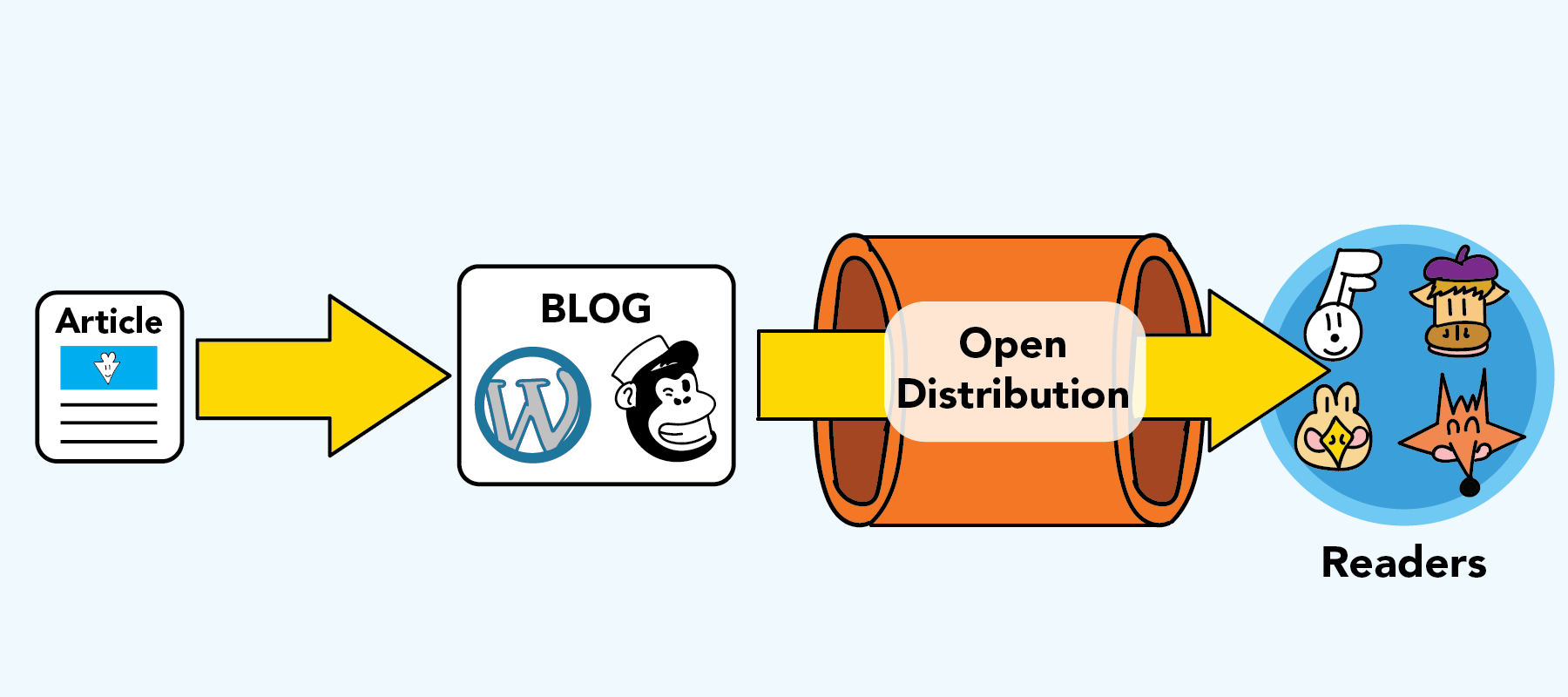

The internet has changed this entire model, thanks to its neat quality of enabling zero marginal costs. A writer’s reach is no longer restricted to the number of physical canvases her work is printed on, as anyone with a computer or smartphone can access and share any article/post. Distribution has been democratized, and tools like WordPress and Mailchimp provide writers with tools to build their own blogs and reach their readers without any traditional publishers involved. This type of direct access allows a writer’s body of work to live on its own, independent of the bundle of advertisements and articles that it previously needed to rely on.

This ability for readers to follow a writer’s work directly is just one side of the equation. On the other side is how readers discover new content, which they previously had to do through buying a newspaper or magazine and coming across work they enjoyed. The brand of the publication was of utmost importance, as the reader would start their discovery process through the publication, and find new writers from there.

Well, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have changed all that.

Much of content discovery now happens through these platforms, and when a reader checks out a link, it’s not because the publication it’s hosted on is compelling; the snippet of content he sees is what’s important. On top of that, if he actually finishes and enjoys the article, his enjoyment will be attributed to the author, thus diminishing the importance of the publication even further.

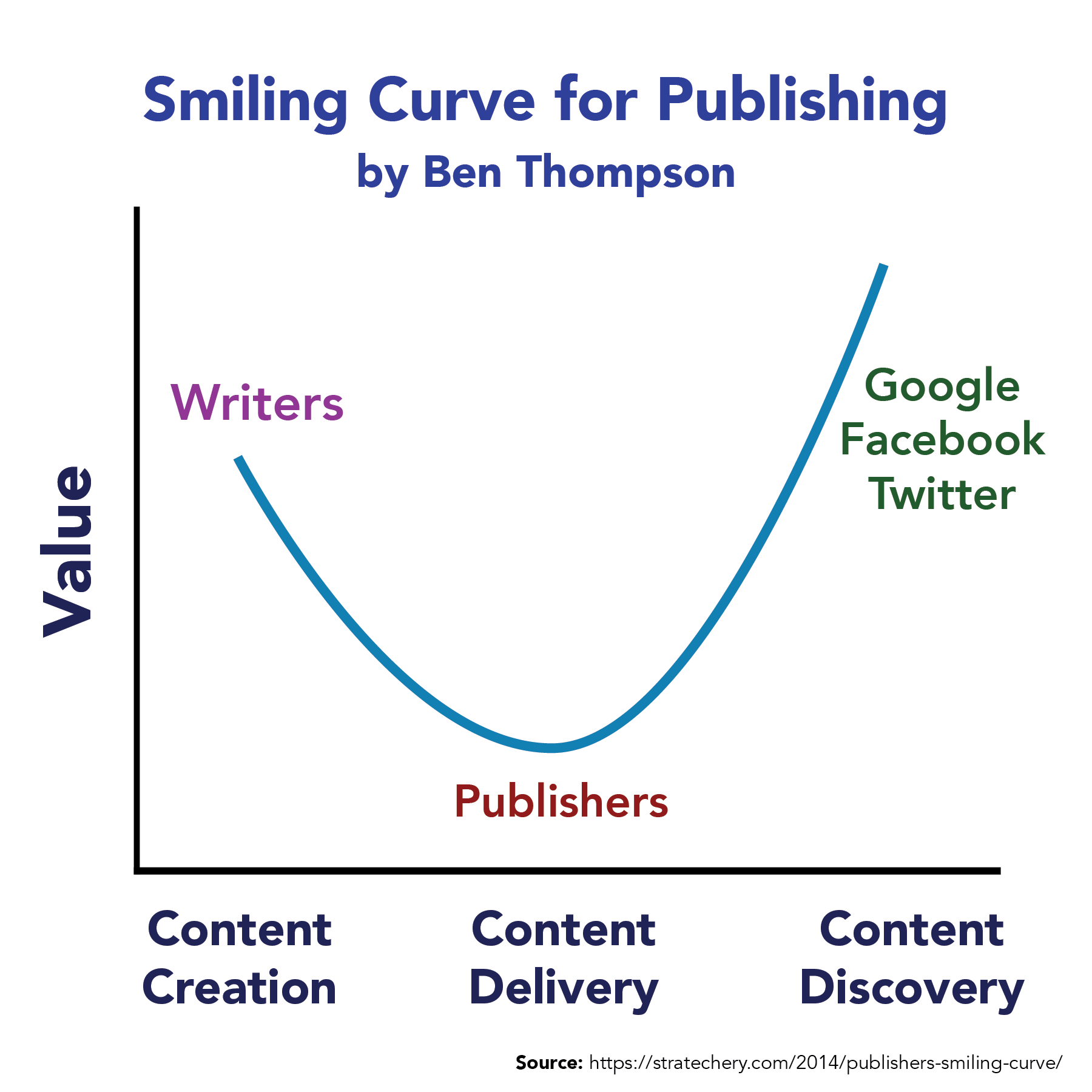

What this means is that in today’s landscape, value flows to the content creators (writers) and the content discovery platforms (Facebook, Google, Twitter), and away from the content distributors (publications). This is illustrated wonderfully in this graph from Ben Thompson’s post, Publishers and the Smiling Curve (I’ve recreated it below for formatting purposes):

This dismantling of the publisher’s value is the second mechanism that enables an obscure node to be “one click away” from a popular one. The internet has made things permission-less; as a writer, you no longer need permission from publishers to run a piece that may lift your work out of obscurity.

There’s no one’s ass you need to kiss, no one you need to rely upon for distribution. You can spend less time pitching stories, and more time doing the only thing that adds value in this chain: writing great content. Readers – not publishers – determine how far and wide your work is spread, and the only way to accomplish that is by writing awesome things that people find compelling, entertaining, or insightful.

How Consistent Writing Fits Into the Picture

It’s true that an obscure node is just a stone’s throw away from a popular one, but hoping that your first blog post catches fire isn’t the takeaway here. You will have to put in many reps, and the only way to do that is to have a consistent writing practice.

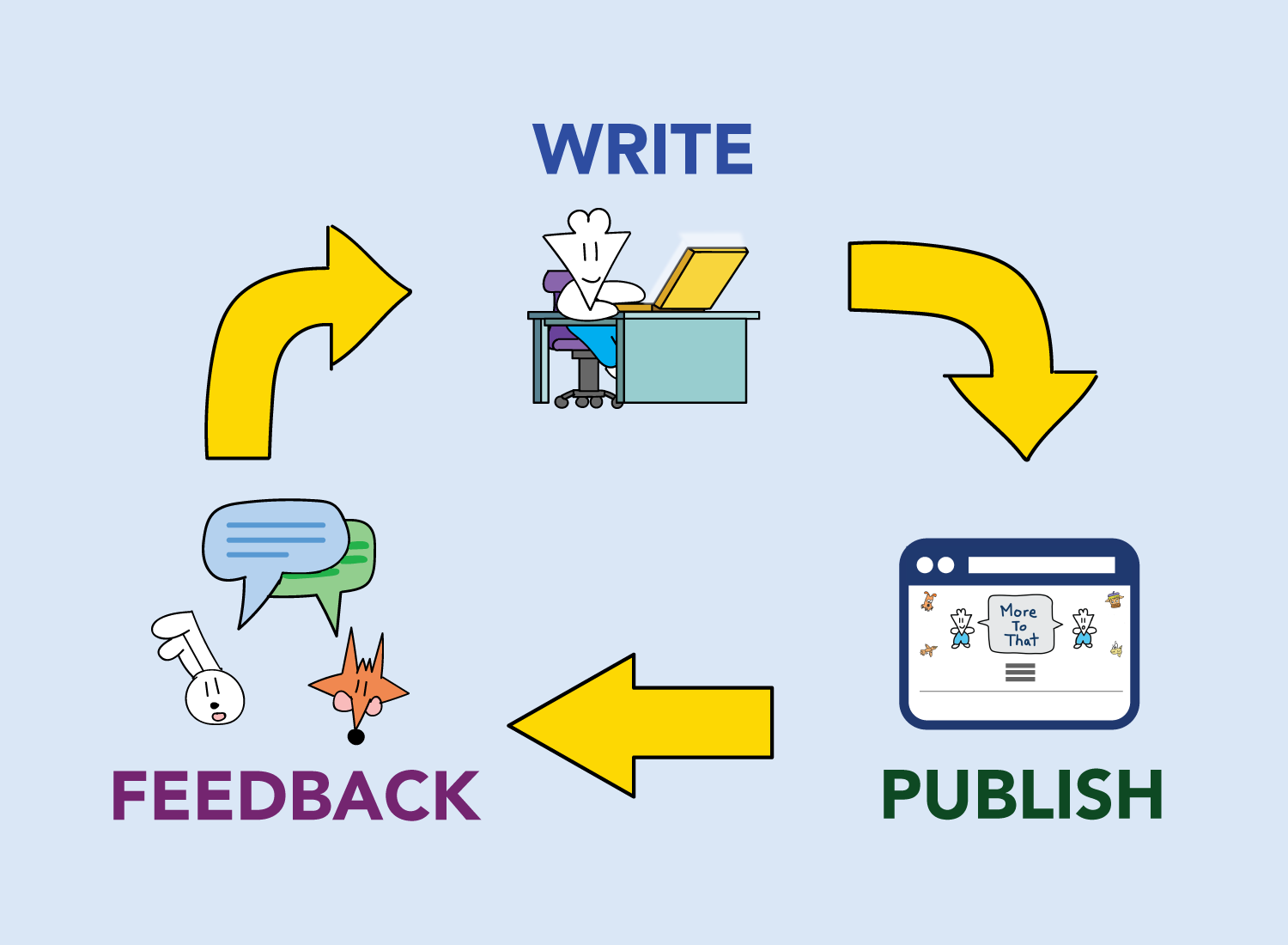

“Show up and write everyday” is not just a cheesy motivational quote, it’s the most sensible strategy given the economics of publishing today. The internet’s enabling of zero marginal costs means that writing is more of an iterative process than it’s ever been. It won’t cost you anything to publish an additional piece of content, and it won’t cost you anything if your work is shared with another person as well. This means that you can experiment with your writing in as many ways as you want, and receive instantaneous feedback as you go (and if something does happen to spread like wildfire, you can sit back and enjoy it).

With this freedom, though, comes a deep authenticity that is now expected from independent writers. If you’re a More To That reader, you know that what you read on this site is coming directly from me, and not from the mouthpiece of a publication that may have some bias or agenda. You are here to access my unique take on things, and it is this authenticity that allows niches to develop around writers that we follow. The writer holds the sole responsibility for articulating his/her thoughts clearly, and quality is an absolute must if we’re asking readers to bypass reputable publications and give their attention to us instead.

This is where consistent writing is the most poignant. I find that writing is essentially the space between what you want to say, and how you end up saying it. The only way to narrow this gap is to write as much as you can, refining your voice and better structuring the thoughts that will turn into your next post. The best part of this process is that you are not alone; the internet has enabled an immediate feedback loop that will give you a good idea of where you are throughout the journey.

Keep in mind, though, that writing alone doesn’t complete this feedback loop. If you want to spread ideas through your writing (and build a career in it), it’s equally important that you publish often as well.

To use a soccer analogy, writing is the series of moves that get the ball to an optimal position in front of the goal, and publishing is the shot that is ultimately taken. The more shots on goal you take, the more you can figure out what works, and the more data points you have to iterate and make better decisions. Thanks to the internet, the distribution of ideas is cheap, but the attribution of value is exponential. Publishing is the only way for that value to begin its accumulation.

It really is amazing. We could have been born at any moment in human history, but here we are, in this tiny window of time where long tails have been empowered, zero marginal costs have been enabled, and smiling curves have lowered the barrier to entry. Never before have writers had the opportunity to build an audience out of nothing, and to do so on their own accord. With this freedom comes a lot of work, but the rewards and connections that can come from them are boundless.

I’m reminded of an ancient Chinese proverb that goes something like this:

“The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.”

This is probably true for most things, but when it comes to writing, I’d argue that the best time isn’t 20 years ago, but now. If you have something to say, this is the time to say it; our chances of reading it are better than they’ve ever been.

_______________

_______________

For another post on content creation and hitting your creative stride:

The Creator and the Crowd: Originality’s Balancing Act

For a stark reminder to do what you’ve always wanted to do now: