The End of Shame

As a parent, you get a front row seat into the development of a human being’s mind.

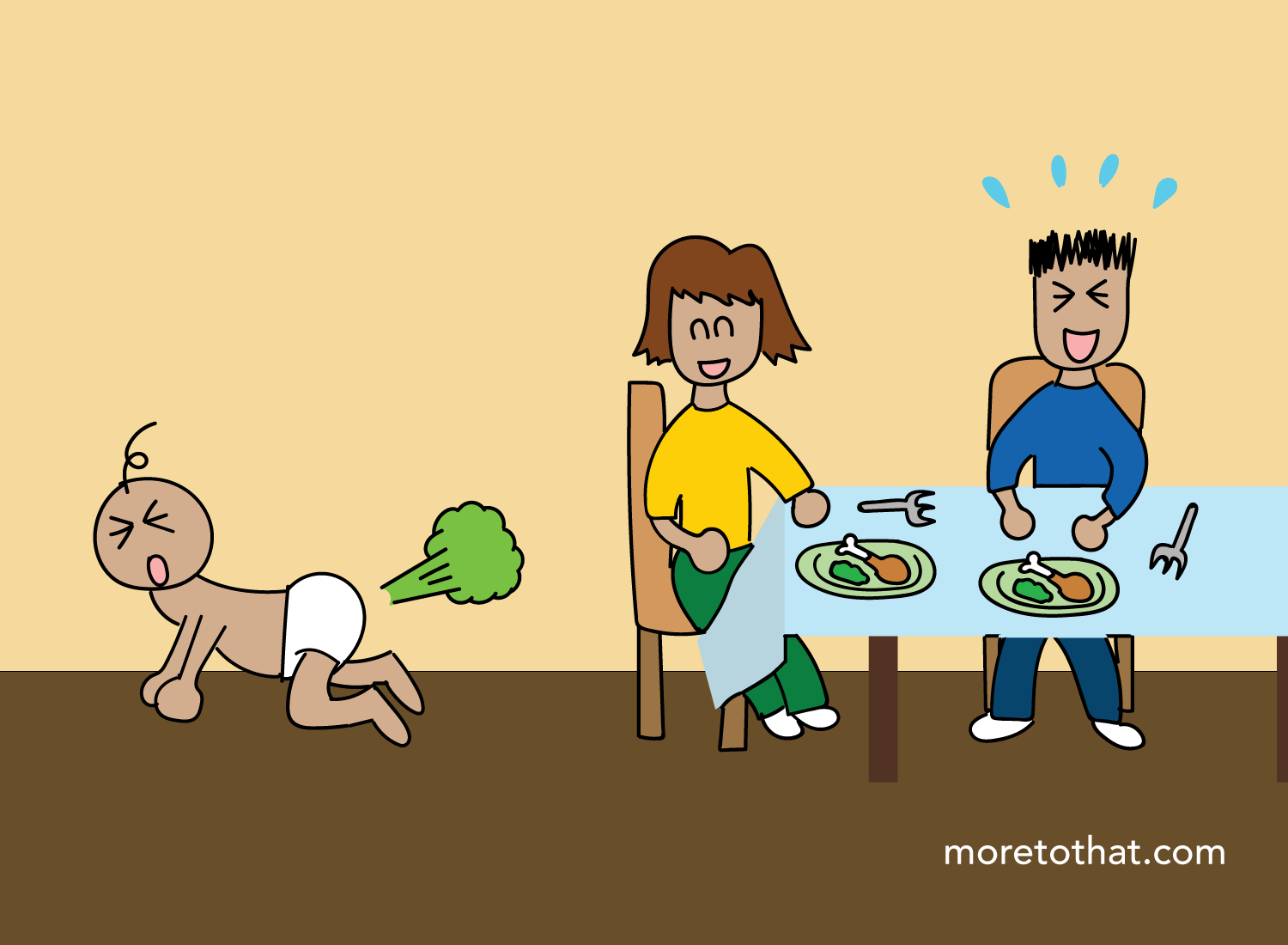

When my daughter was a newborn baby, all that mattered was her physical survival. The primary function of her mind was to alert us of her many discomforts, most of which revolved around requiring food or needing to dispose of it.

As she exited infancy and entered toddlerhood, there was a transition of another kind. Her mind went from solely mediating her biological needs to also monitoring her psychological ones. What was previously a bloodcurling cry for milk evolved into a silent shyness when asking for more at school. Her emotions were becoming more nuanced, and the fascinating thing was that she was becoming aware of this too. In fact, this awareness is a defining period of childhood for all of us.

What triggers this awareness is the realization that you are in relationship with others, and crucially, with those you don’t know that well either. When you’re an infant, all that matters is that your biological frame is intact, and you’ll scream at the top of your lungs to ensure that it is. Fortunately, the people that receive this scream are your parents, who have the patience to ensure that you’re okay.

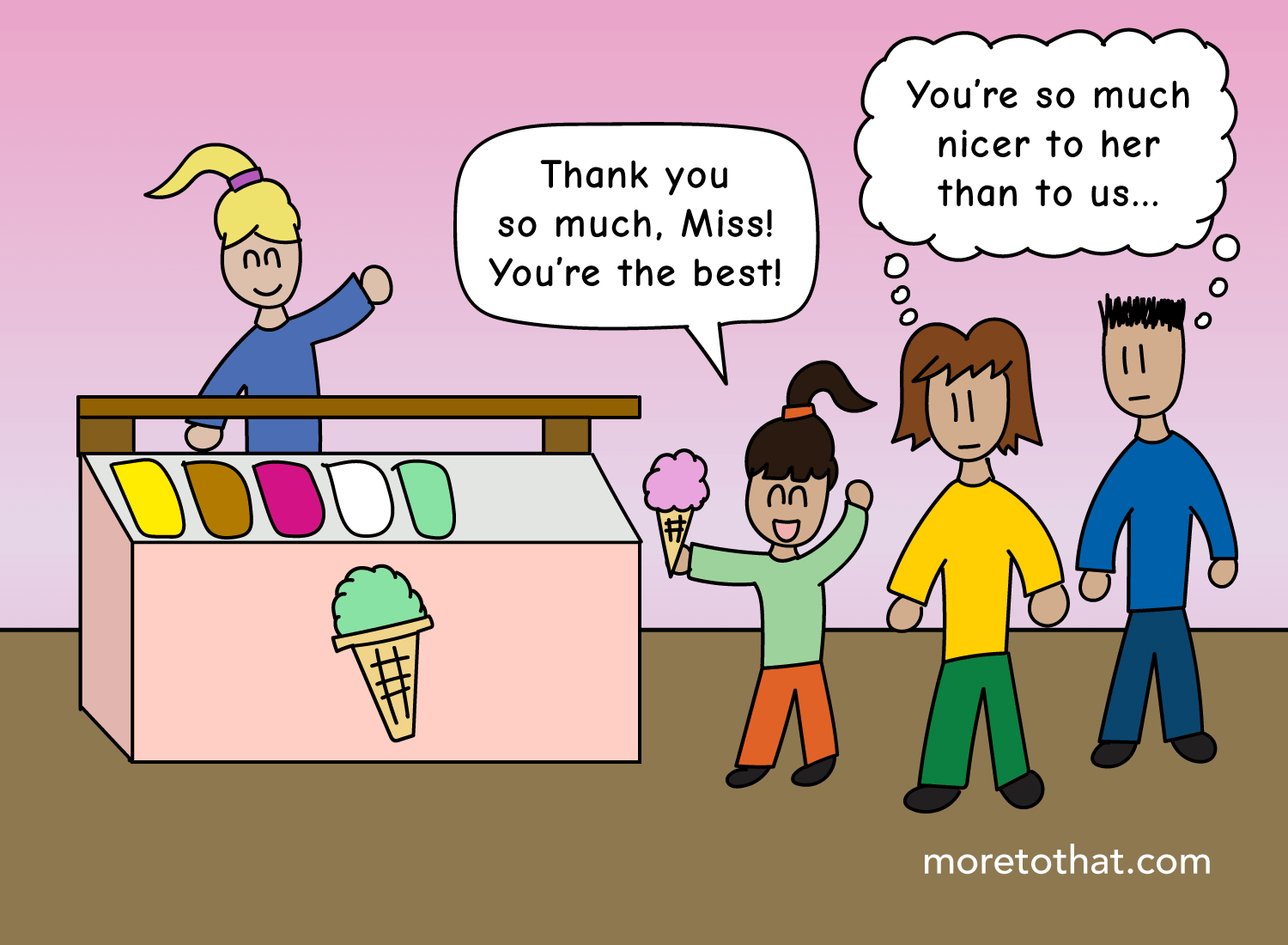

But as you get a bit older, you notice that the same dynamic you have with your parents doesn’t apply to other people you meet. Whether it’s your grandparents, your friends, or even the nearby ice cream shop owner, each relationship contains its own culture that distinguishes it from all the others.

In other words, you begin to notice that the self is a social construct. There isn’t this static “you” that stays the same across all interactions; rather, there are certain parts that come out with some people and some parts that don’t. Of course, as a child, you can’t conceptualize it as a “social construct,” so your emotions do the legwork for you. With some people, you’ll feel at ease. With others, you’ll feel a bit nervous. The way you feel becomes an indicator of the dynamic you share.

The benefit of this truth is that it acts as a great source of meaning. Because you gain access to so many parts of yourself, you realize that there’s so much that you’re capable of. Knowing that you’re malleable instills a sense of confidence that you can navigate the world, allowing you to successfully collaborate with the people within it.

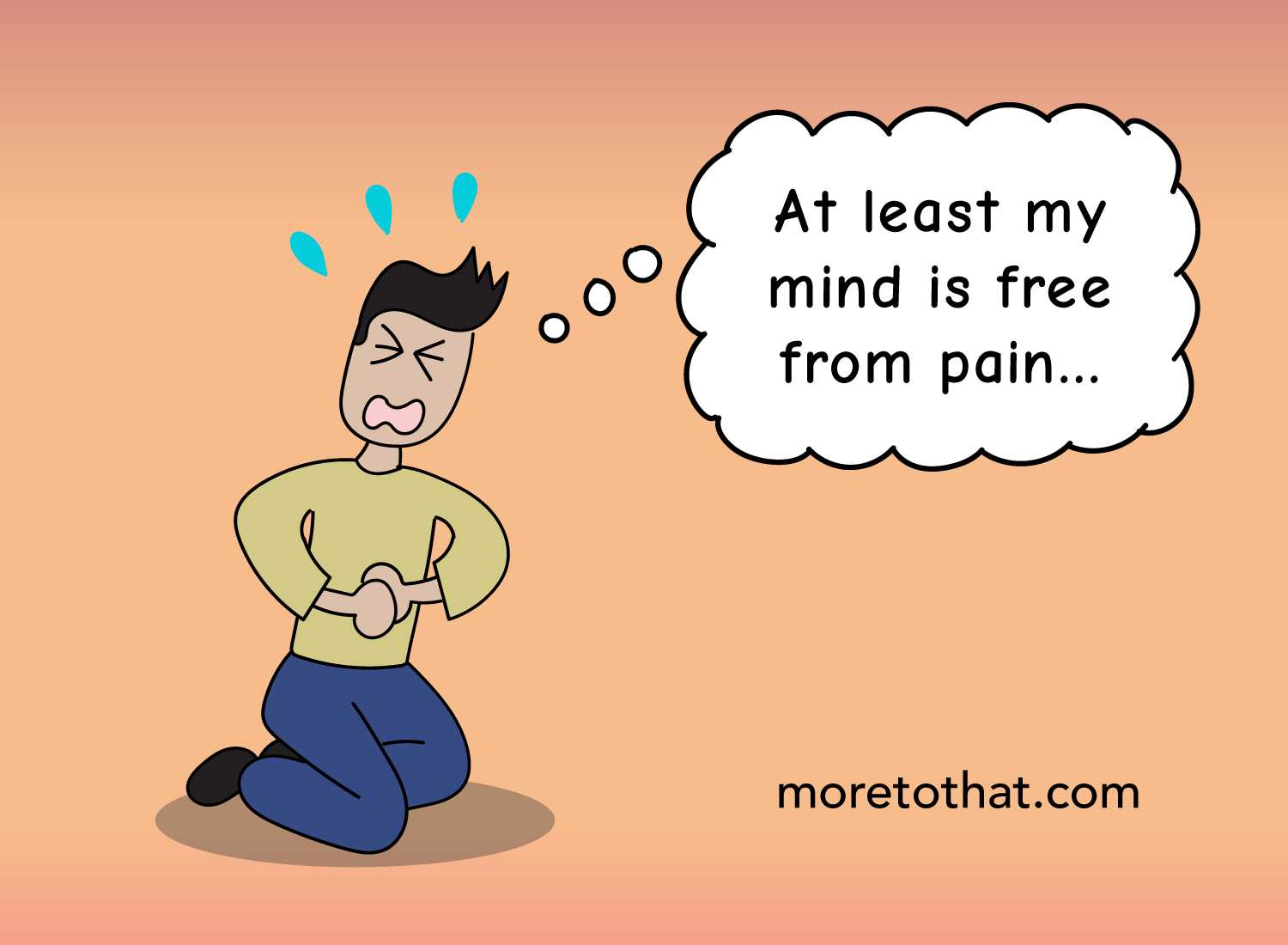

But the burden of this truth is that you begin to define yourself by what others think. If you are indeed a social construct, then your sense of self-worth is derived from the judgments you receive from others. This is why an attack on one’s reputation is akin to an attack on one’s body. The pain one feels when their reputation is in jeopardy is just as salient as a gut punch to the stomach.

In fact, many people would prefer the punch.

Perhaps the greatest manifestation of this burden comes in the form of shame. We tend to view shame as a circumstantial emotion, where it arises as the result of something you said or did. But if that were the case, then it would be a very short-lived thing. You’d apologize to the other, forgive yourself, and let it go. If it were truly circumstantial, then that quick process is all you’d need.

I notice this in my daughter, where anytime she thinks she did something wrong, she’ll sincerely apologize, check to see if things are okay, and then moves on with life. She doesn’t feel a lingering sense of self-hatred that she can’t shake off beyond the moment.

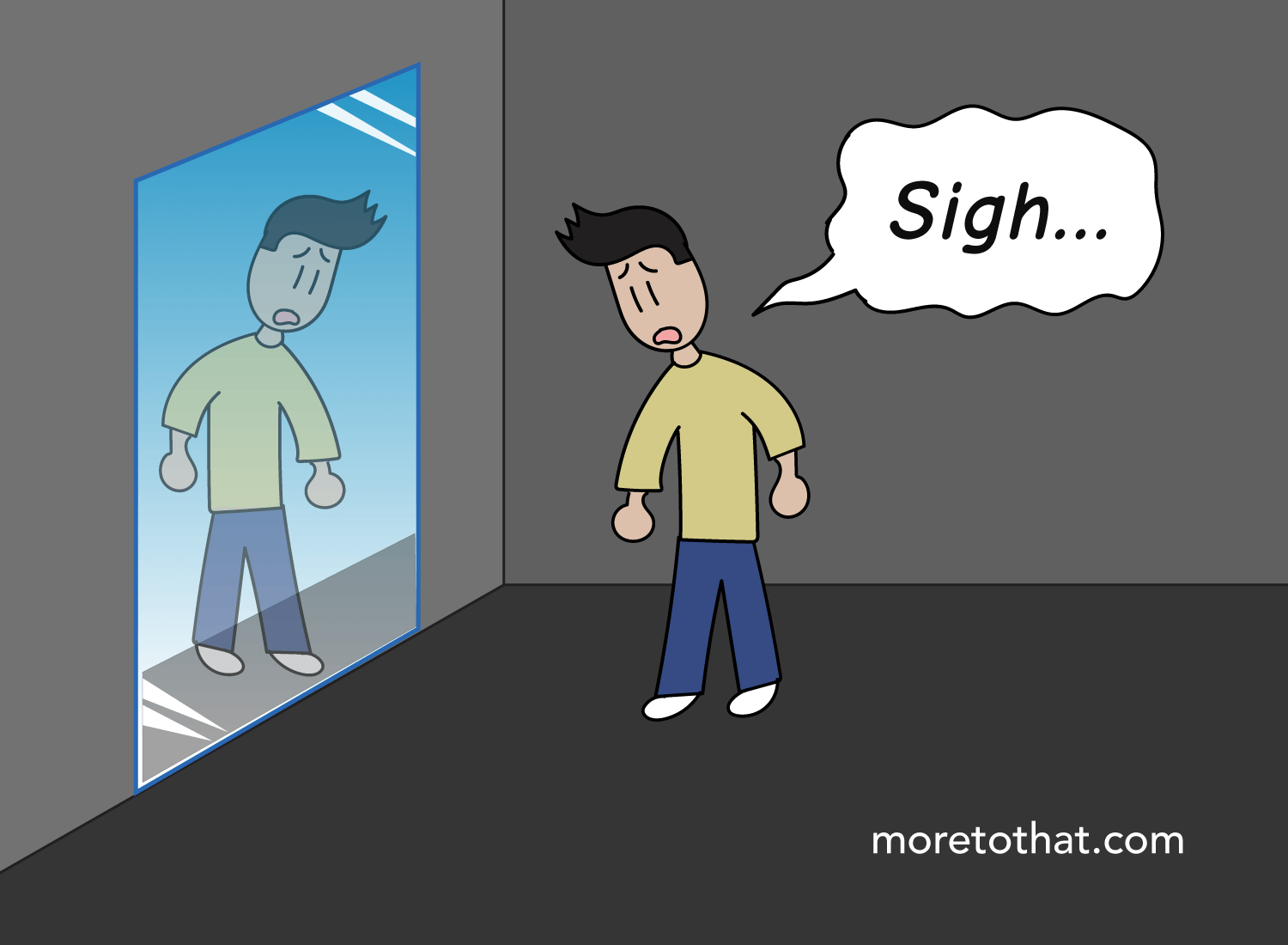

Shame is not that. Shame stays with you, and makes it feel like there’s something inherently wrong with you. It’s deeply rooted in the body, as merely thinking about the objects of your shame will conjure a slew of sensations that you can’t ignore. Feeling shame isn’t isolated to an action or two; rather, you begin to feel that your entire being is something to be denied.

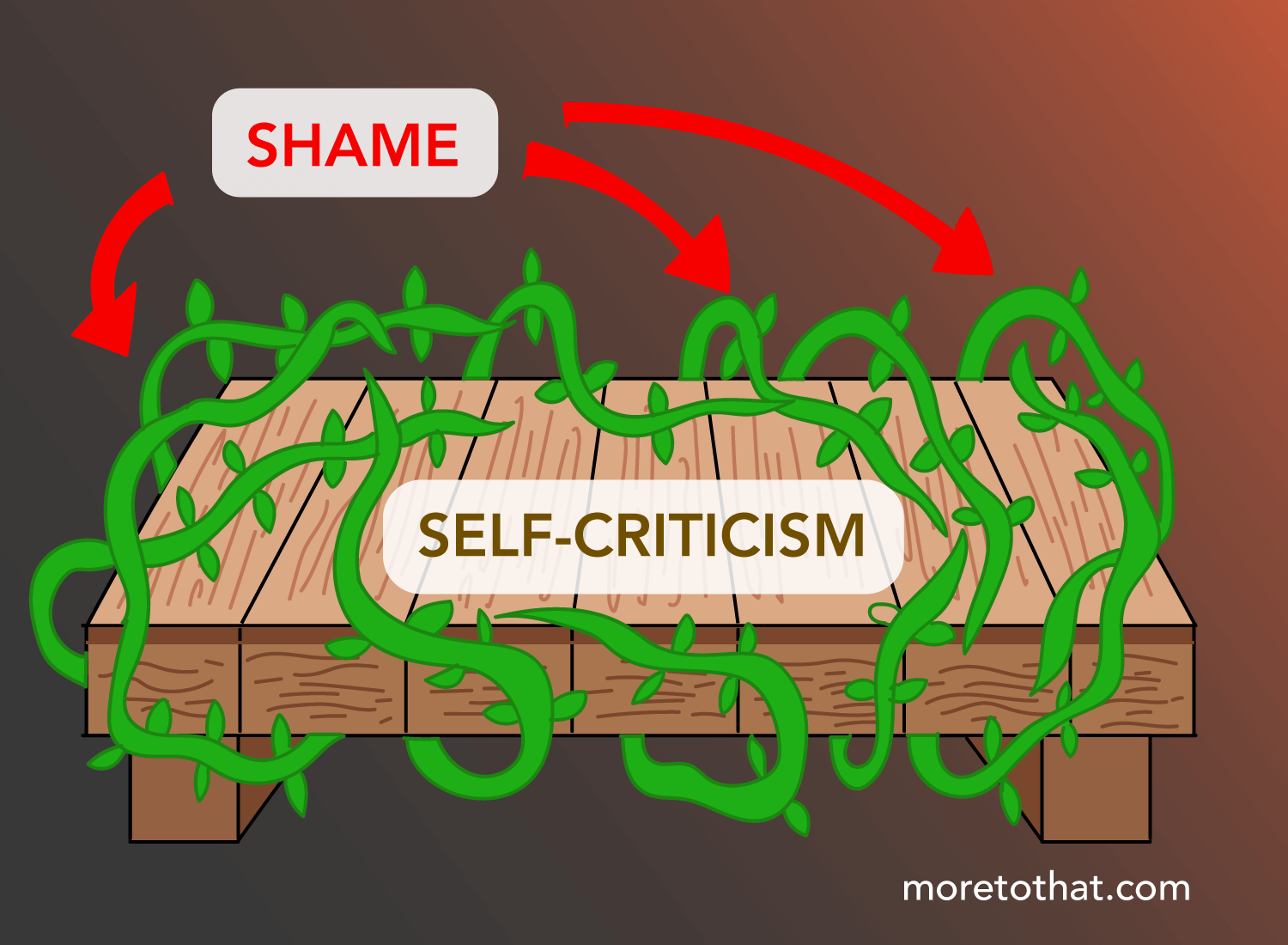

What makes shame so pernicious is that it doesn’t take much from the outside world to install it. Of course, a negative comment can agitate it, but what keeps it alive is the narrative you tell yourself about that comment. For example, if someone said that you chose the wrong career, that statement will convert to shame only if it coincides with the story you tell yourself about your career as well. You had to already have deep doubts about your work in order to feel the shame that arises from someone saying that you’ve failed at it.

The same thing applies to relationships. You will only feel shame if you believe that you haven’t been the best partner, family member, or friend. There has to be an initial platform of self-criticism in order for shame to take hold and grow.

Now, in some cases, this dynamic is useful. People that have deeply harmed others, for example, need to be critical of their own actions in order to apologize and redeem themselves. Feeling ashamed of what they did is a reliable indicator that they have an inner compass that is seeking to be recalibrated. In these cases, shame becomes a corrective mechanism that helps to direct them toward a brighter path.

The problem, however, is when shame becomes chronic and is embedded into one’s identity. The trigger for your shame may have occurred years ago, yet you still feel it to the core of your being. This is a sign that shame has spread well beyond the domain of any single action, and has become a part of the way you view your sense of self.

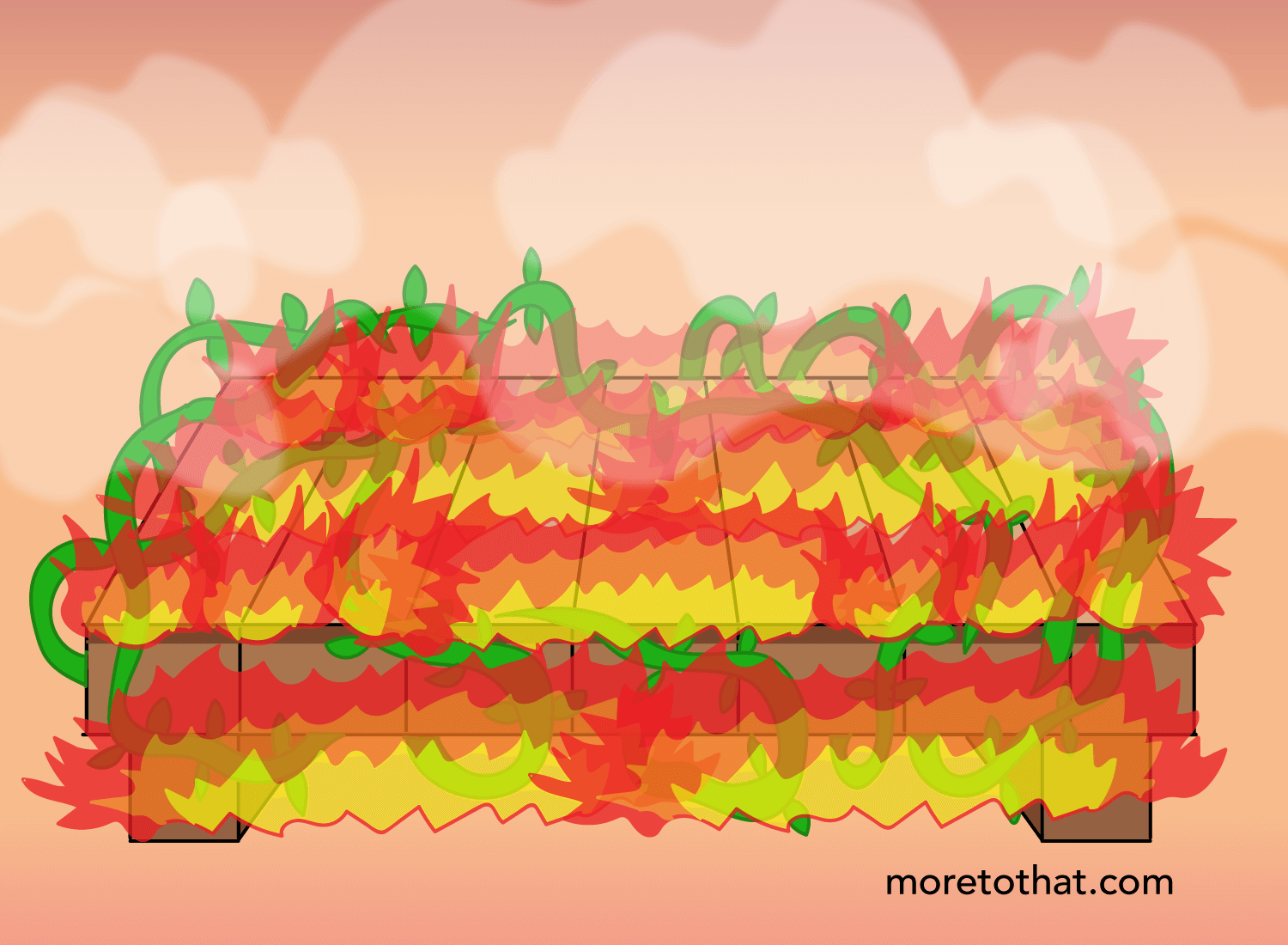

This is when shame needs to be extinguished, and the only way to do that is by radically resetting any self-critical narratives you have. You have to burn the whole edifice down, knowing that it’s not producing anything useful or insightful for you. Any resistance you have to doing this is shame’s way of clawing for survival.

The key is to ignore its plea, and to perform the reset you so desperately need.

Feeling shame about your career? Tell yourself that you’re exactly where you need to be right now.

Feeling shame about a relationship? Tell yourself that you’ve done what you can to get it to where it is.

Feeling shame about your body? Tell yourself that your body is a gift that enables you to navigate the world.

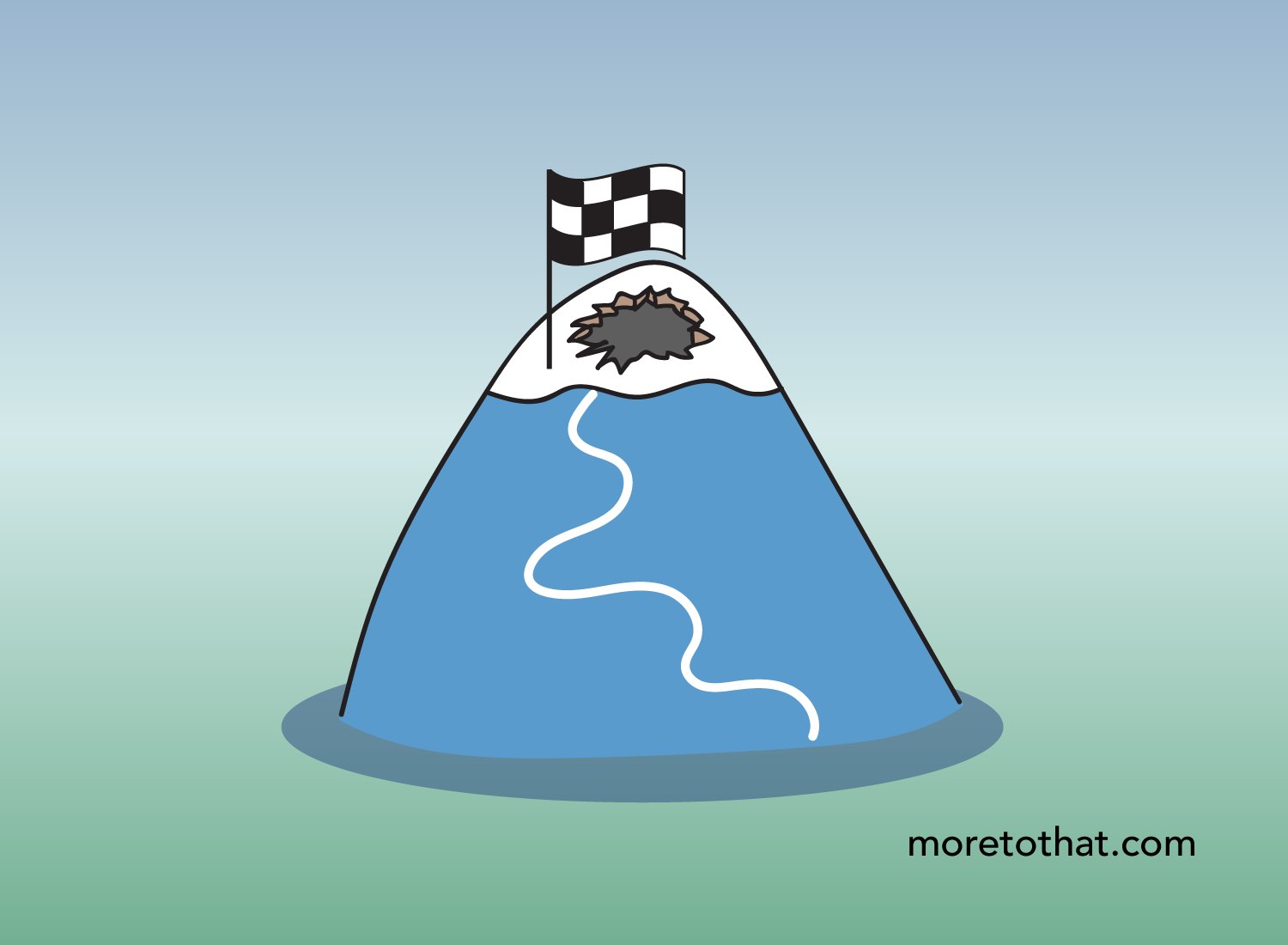

Some of you may read those statements and think that I’m advocating for complacency. While that may make sense at first glance, what you’re missing is that shame is a poor conduit to empowerment. People that are shamed into improving themselves will never feel secure in who they are, even if they do reach the heights of success. As long as shame is the propelling force behind any goal, what awaits beyond the finish line is an existential crisis that will unravel everything that was earned up to that point.

The antidote to shame is self-love, and it is only through this internal force where true empowerment is possible. You don’t change for the better because other people make you feel inadequate; no, you do it because you respect yourself. When you build off a foundation of self-love, then everything that results comes from a deeply authentic place.

The key is to remember that self-love doesn’t mean complacency. Nor does it mean lethargy. If anything, loving yourself requires a lot of work, primarily because when you have self-love, you become aware of the potential that lives within you. You understand that you’re not a mere summation of social expectations, but that you have the personal agency to be the best version of yourself.

Self-love isn’t the presence of narcissism, but the absence of criticism. The person that aggrandizes himself is secretly seeking the approval of others, which makes him vulnerable to what people think. But the person that has compassion for herself builds a quiet confidence that requires no other voice to be validated. And it is on this frontier of acceptance where one meets the end of shame.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

Self-doubt is a common manifestation of shame. Here’s how to end that too:

A big part of ending shame is to understand how the sense of self develops over time:

Shame dissolves once you question its underlying beliefs. Here’s a post that can help with that: