Do You Really Believe What You Believe?

Every now and then, I’ll do something that’s particularly unwise. I’ll hop on Twitter, and check out what’s going on in the world of politics.

I’m still not sure why I occasionally venture out there, as I’m 100% convinced that paying attention to politics leads to unclear thinking. Perhaps it’s my little way of going on a thrilling, irrational adventure no one asked for, or maybe it’s just the intellectual version of picking at a scab – you know you shouldn’t do it, it hurts when you actually do do it, but you find yourself doing it anyway.

Needless to say, every time I venture out into this realm, I come across all sorts of weird human behaviors – behaviors that prove the existence of an alternate dimension that’s been made possible by the internet.

I see people saying things that they’d never say to others in real life…

…people making ridiculous claims, which are further amplified by others…

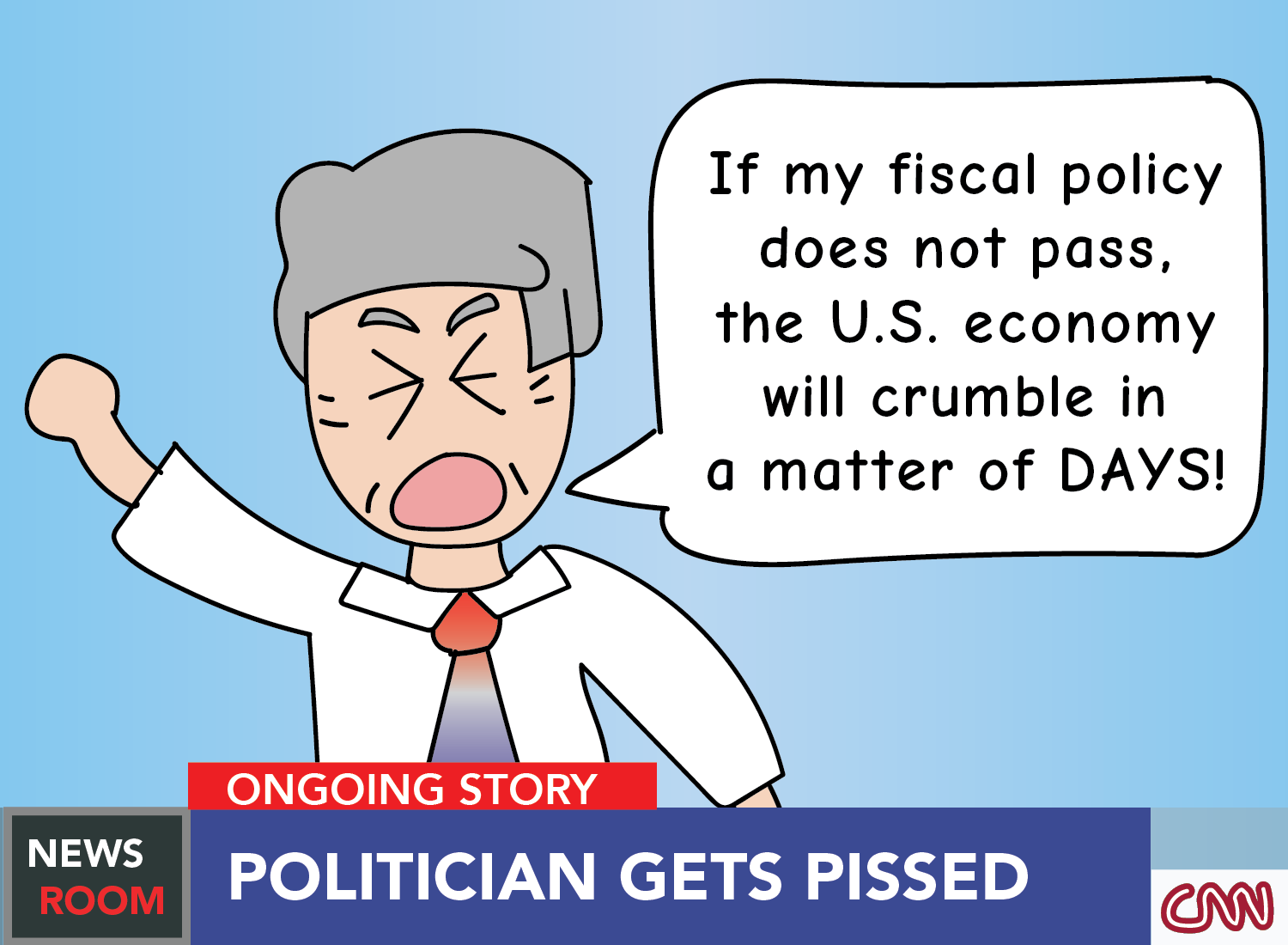

…and of course, let’s not forget about the wonderful things politicians say.

More often than not, when I come across a controversial clip of some politician talking, the sentences coming out of his or her mouth appear nonsensical and outlandish. It doesn’t matter what color tie the politician is wearing, or what topic is being discussed. There is an interesting blend of confidence and closed-mindedness constructing this person’s position, and I find myself wondering the same thing whenever I watch one of these clips:

Sadly, this question is all-too-common, but an all-too-important one to consider.

We live in an era where every person with an internet connection has a voice, and the volume of that voice can be amplified at any moment. What is spoken or stated is the only way to gauge someone’s stance on an issue, but it’s impossible to know what the person really thinks about it. Are the individual’s words a true representation of his beliefs, or are they merely a signal being used to direct people to a personally useful, but knowingly false position?

We can’t worm our way into the heads of people to get a concrete answer, but we can try to model this out to get closer to what’s really going on.

Let’s take the case of the heated politician, who claimed that the United States’ economy will crumble in mere days if his fiscal policy doesn’t pass.

We will illustrate this belief with this green stone:

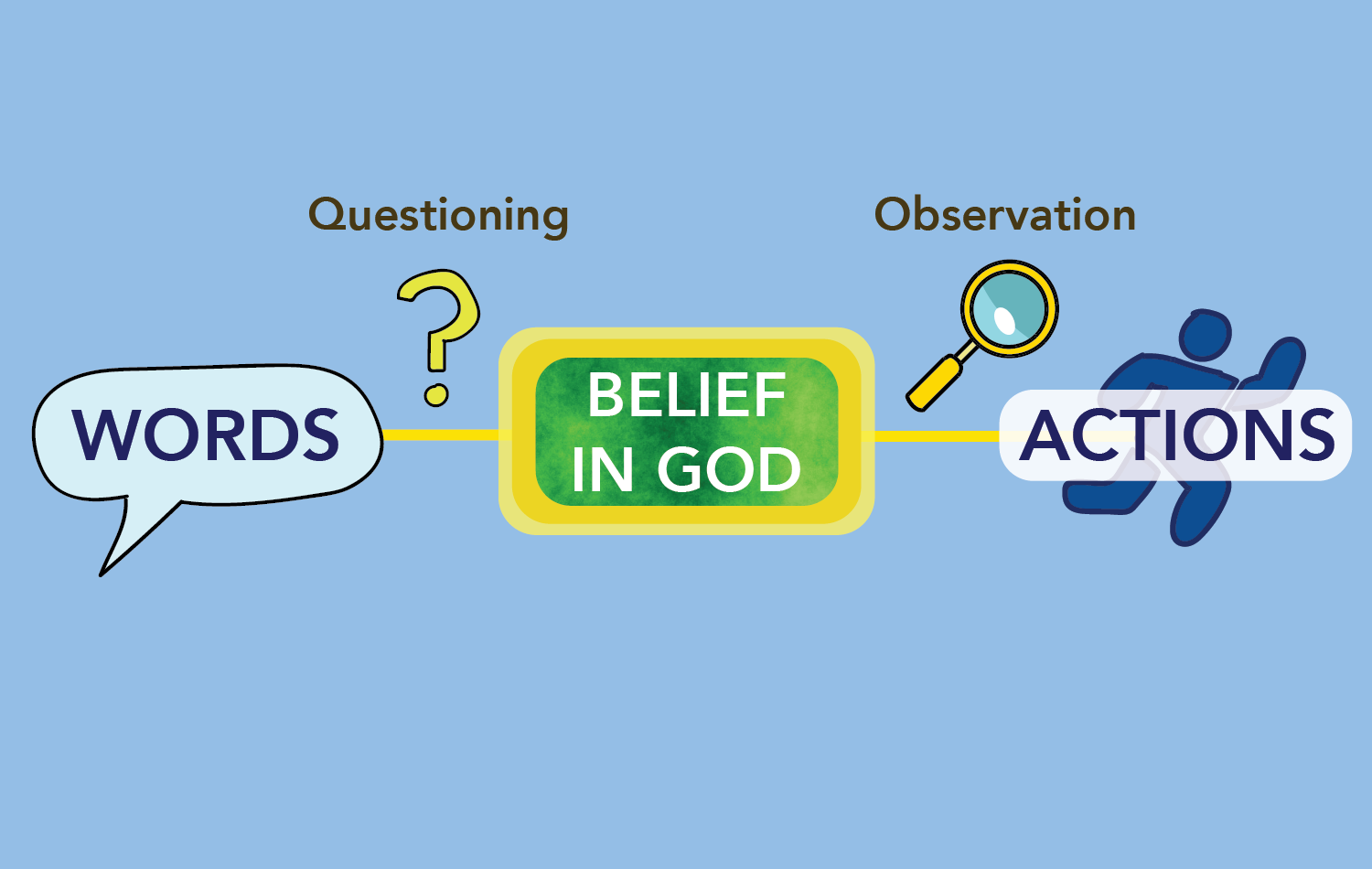

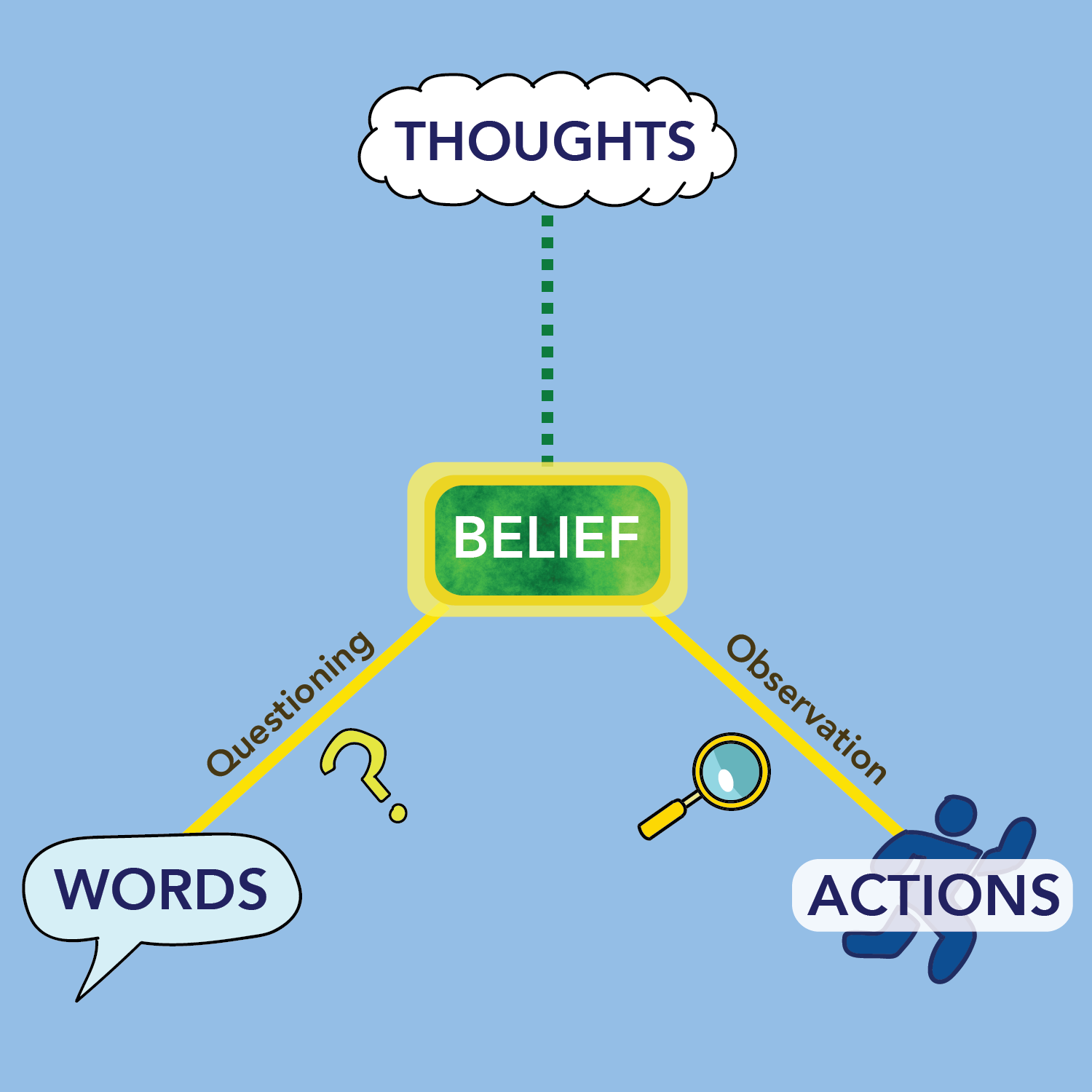

We want to determine if the politician really does believe this, and will go through some methods of belief-testing to see if this is the case. Most of the time, however, all we have are his words, which are supposed to reflect and connect with his belief.

Words are a crude representation of someone’s thoughts, and there’s really just one way to test if they accurately depict a belief. This is done largely through the tool of questioning (made popular by Socrates), which forces the individual to articulate his or her position in a way that aligns with the stated belief.

In the case of our politician, we can ask him why he believes that the economy will crumble if his policy isn’t passed, and how he gathered the evidence behind the claim. In an exceptionally rare case, the politician may pause while answering a question, and simply admit that he doesn’t really believe what he said. If this happens, then the case is closed; the belief doesn’t hold.

However, both you and I know that this isn’t going to happen.

Words are cheap yet defensible; they’re uttered at no cost, but hold immense power. It’s effortless to tell a lie, but devastating to reveal that you are a liar. Sadly, the incentives are such that it’s rational to defend your position with words, given their ease of use and weight they hold. So we need a better mechanism to test belief that has a higher price of admission.

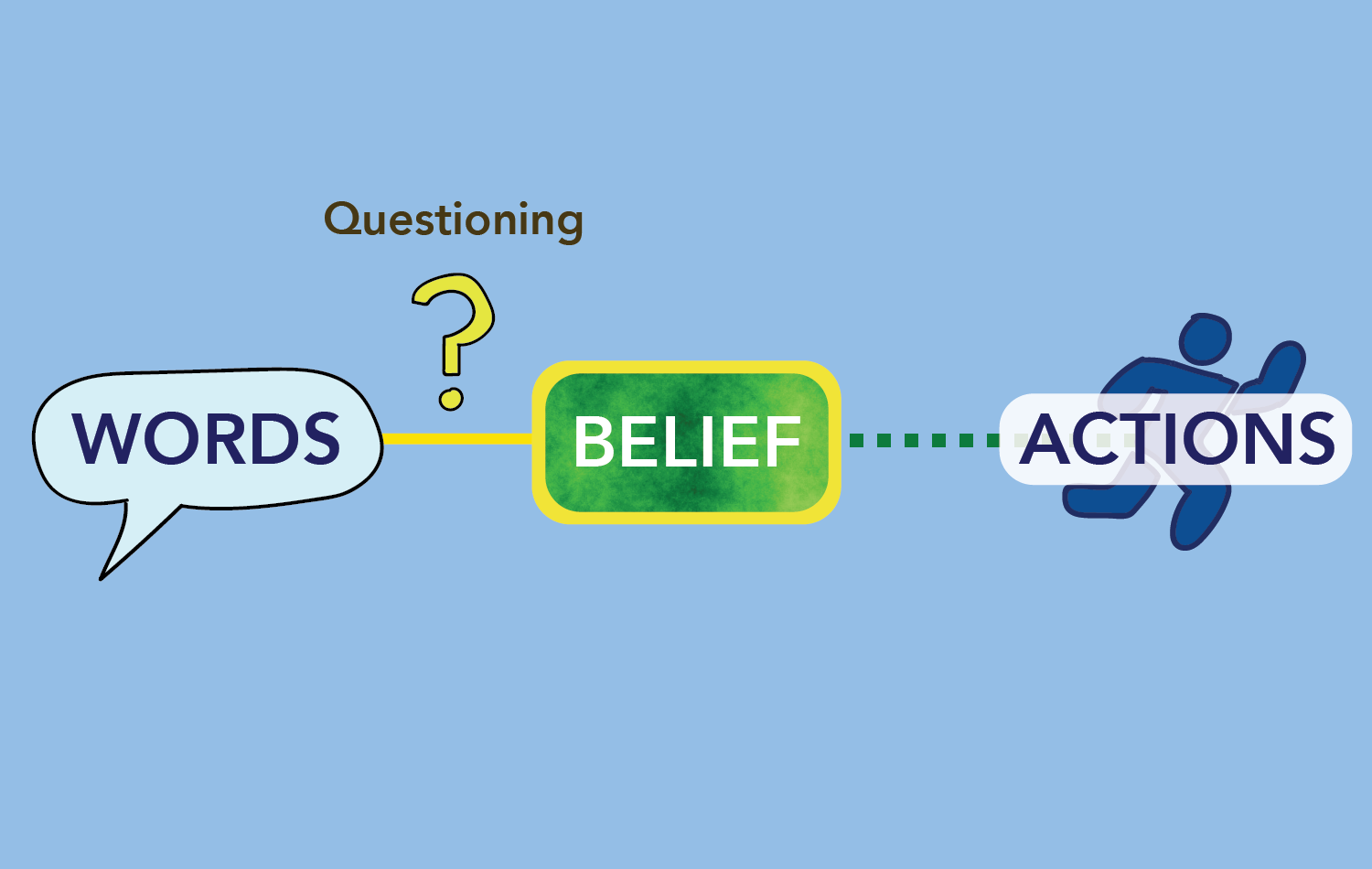

This is where one’s actions come into the picture.

Actions are the higher resolution images of belief. They provide a more detailed look into one’s belief systems because they require investments of energy, resources, and time, making them much better indicators of truth than words. The incentives are aligned because your reputation and personal gains are attached to what you do, and what you do is expected to be linked to what you believe.

This expectation, however, cannot simply be assumed. It must be rigorously tested, just like words are tested with questions. And the only way to validate one’s actions is through the tool of observation.

Observing one’s patterns of behavior is an effective way to see if their stated beliefs hold. In politics, this is why good journalism is so important. The public only sees and hears what the politician says, but since talk is cheap, it’s an unreliable window into the politician’s actual thoughts. What journalists do is observe the politician’s actions – from who they are in touch with to what type of financial dealings they’re a part of – and convey a better understanding of the politician’s true belief systems to the public.

For example, if journalists discovered that our “economy-will-be-ruined-in-a-matter-of-days” politician was aggressively shorting the market,1 that may suggest a deceptive motive for his fear-mongering. It’s not that he actually believes that the economy will collapse in a few days, he just has a lot to gain if others believed that it did.

Of course, the link between action and belief extends well beyond politics, and into all facets of everyday life. It’s one of the most reliable ways to determine who we keep as friends, who we do business with, and who we choose to read or listen to. Whether we realize it or not, we are in a perpetual state of observation, fine-tuning our intuitions so they better reflect who is trustworthy, and who is to be avoided.

Evaluating one’s words and actions get us close to what one truly believes, but it’s unclear if this completes the picture.

Let’s say our politician ardently sticks to his claim, both in what he says and what he does. All that is well, but…

…it’s just hard to deny that there’s still something really off about his belief. How can he really believe that the U.S. economy – an incomprehensibly massive engine of systems and behaviors – will be wiped out if his little policy proposal isn’t passed? How can he possibly think that he would have that much influence? Does he even realize how implausible this sounds to others?

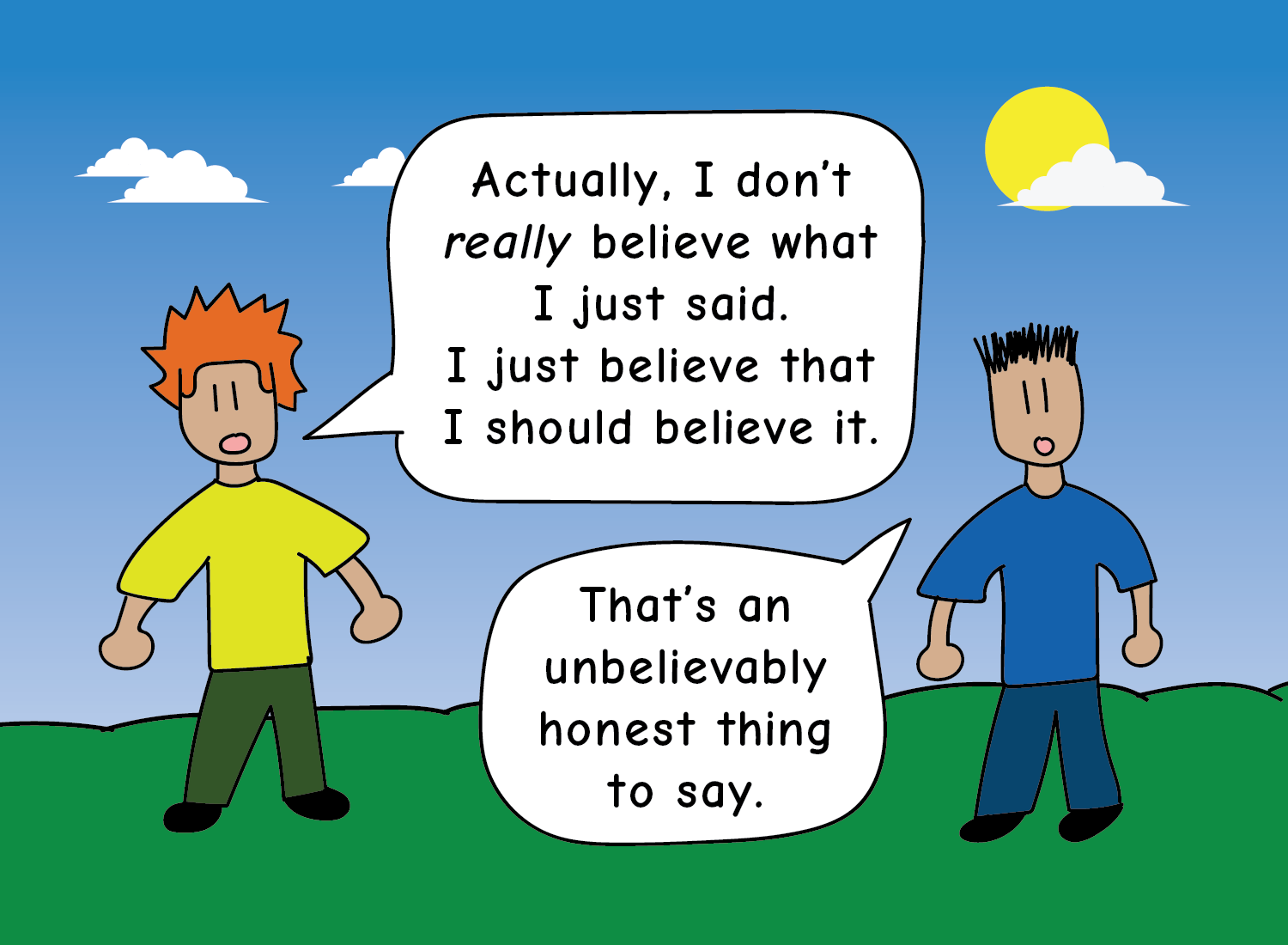

This is where the most interesting part of belief comes in. The politician may speak, act, and even think in a way that’s fully aligned with his claim, but he can actually do this while simultaneously knowing that the belief is false. In other words, it’s possible that the politician knows the claim is not true, but he thinks that he is supposed to believe it regardless.

This feeling of believing that you should believe something – despite realizing its falsity – is what philosopher Daniel Dennett calls “belief in belief.” It’s a shield that can be used to protect a belief from further scrutiny, as it prioritizes the benefits of a belief over the truth of it.

This can all sound a bit abstract, so let’s go concrete for a moment, using an example that is sure to be void of any controversy.

Let’s all say hi to Tom.

Tom is a man that believes in God.

Tom says that he believes in God every time someone asks him about it, so his words are aligned with his belief.

Additionally, he goes to church every Sunday with his wife and kids, tithes 10% of his income, sings all the praise songs, prays before every meal, and attends bible studies every other week.2 His actions seem to align with his belief in God as well.

It appears that Tom has satisfied the necessary conditions for belief, but the tools of questioning and observation can only be validated externally (from an outsider’s perspective). So what is going on with Tom internally, or more specifically, what are his own thoughts about his belief in God?

Well, it turns out that Tom has been wrestling with that a lot lately. He’s a big proponent of science, loves reading philosophy, and has questioned many of the things that his religion embodies. He thinks that evolution is the real nature of our species, and that creationism is a myth. He also doesn’t quite understand how an all-compassionate God could bring about so much evil in the world,3 which has made him doubt God’s very existence as well.

Despite these serious doubts, however, Tom believes that he should live as if he believed in God’s existence. Even though he questions it, he thinks that it is a virtuous, proper, and beneficial thing to carry onward anyway. After all, it’ll be good for his children to go to church, be a part of a community, and have the opportunity to be around good people. He tells himself that it doesn’t really matter if he actually believes in God, it just matters that he believes the belief is true.

From the LessWrong blog:

As Daniel Dennett observes, where it is difficult to believe a thing, it is often much easier to believe that you ought to believe it.

This type of self-convincing behavior in the face of contradictory truth is what is meant by “belief in belief.” It is a powerful force that evades rationality, and it extends well beyond religion.

For our wonderful politician, he probably doesn’t really think that the economy will crumble in days, but believes that he ought to believe it. Perhaps getting his policy passed means that he’ll finally be accepted as a member of his party’s elite, and that will lead to a better life for him and his family. Maybe he believes that his false message to the people will get them to react swiftly, and that will ultimately be a good thing for the direction of the country. It feels important for him to believe as if his belief were true, because doing so would benefit him greatly.

What this confirms is that one’s thoughts are the closest representations of belief we have. Words and actions are mere signals of a belief, but only thoughts reveal true intentions. We can say things we don’t believe, we can do things we don’t believe, but we cannot think things we don’t believe. If you think you can, then you are just doing that “belief in belief” thing, deceiving yourself in the process.

The problem with thoughts, however, is that we can’t validate what they are in others. This is frustrating, given that we started this post trying to figure out if we could determine if someone really believed what they said. Unfortunately, this is largely a futile exercise – people won’t admit that they believe in belief unless they’re unusually aware of their own lack of honesty.

So when it comes to others, beliefs can only be tested externally. The belief-testing structure is linear, with the questioning of words on one side, and the observation of actions on the other:

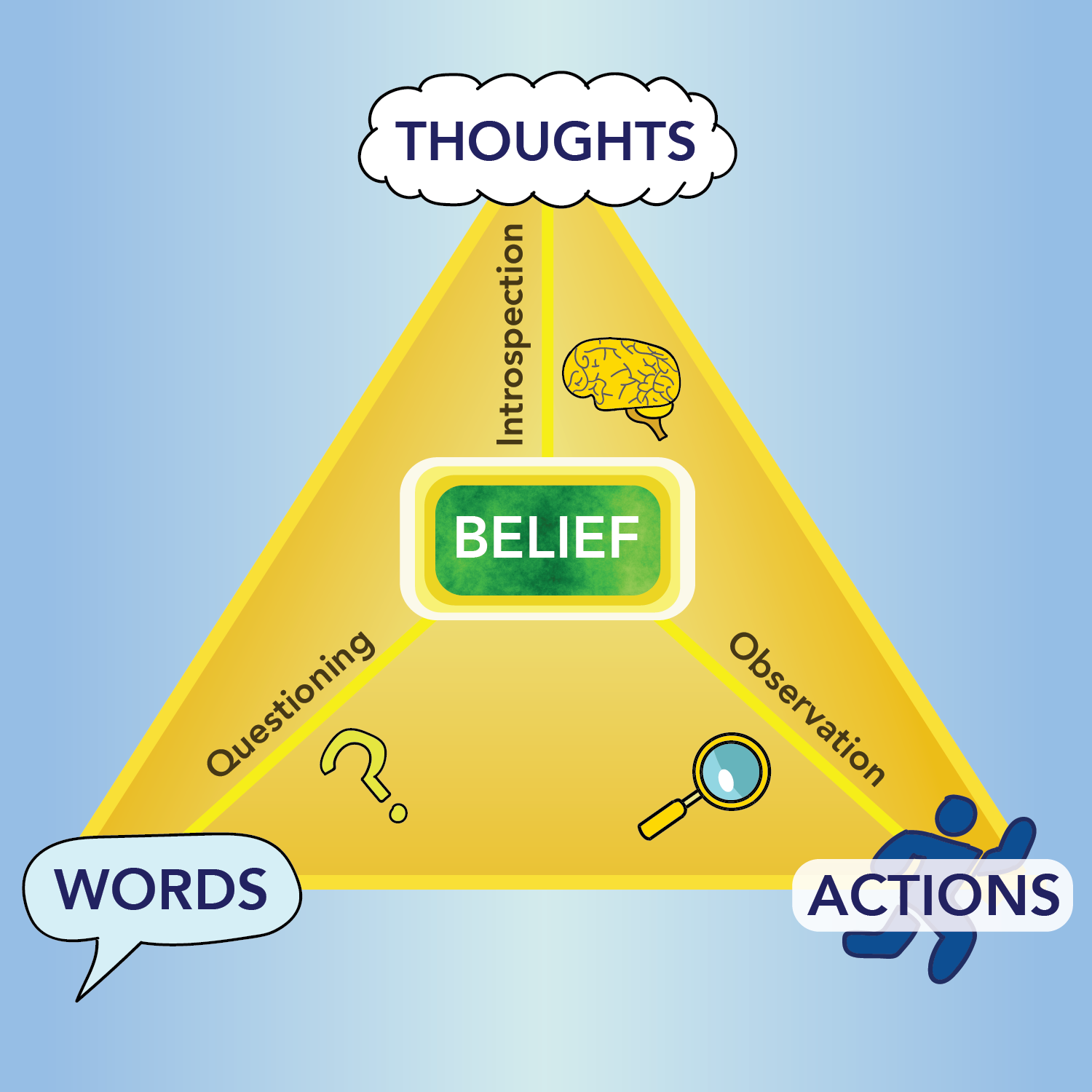

However, when it comes to ourselves, the structure changes.

We have direct access to our thoughts, and we can test our beliefs internally through personal experience and knowledge. We can be honest about whether we really think a belief is true, or if we’re just believing as if it is. And the only way to test this link between our thoughts and belief is through the tool of introspection.

This complete model is what I call the Belief Triangle, and is what I use when surveying my views of myself and the world. This framework determines whether or not my words, actions, and thoughts are aligned with what I think I believe. If they are, then this is a belief that represents my honest view of reality.

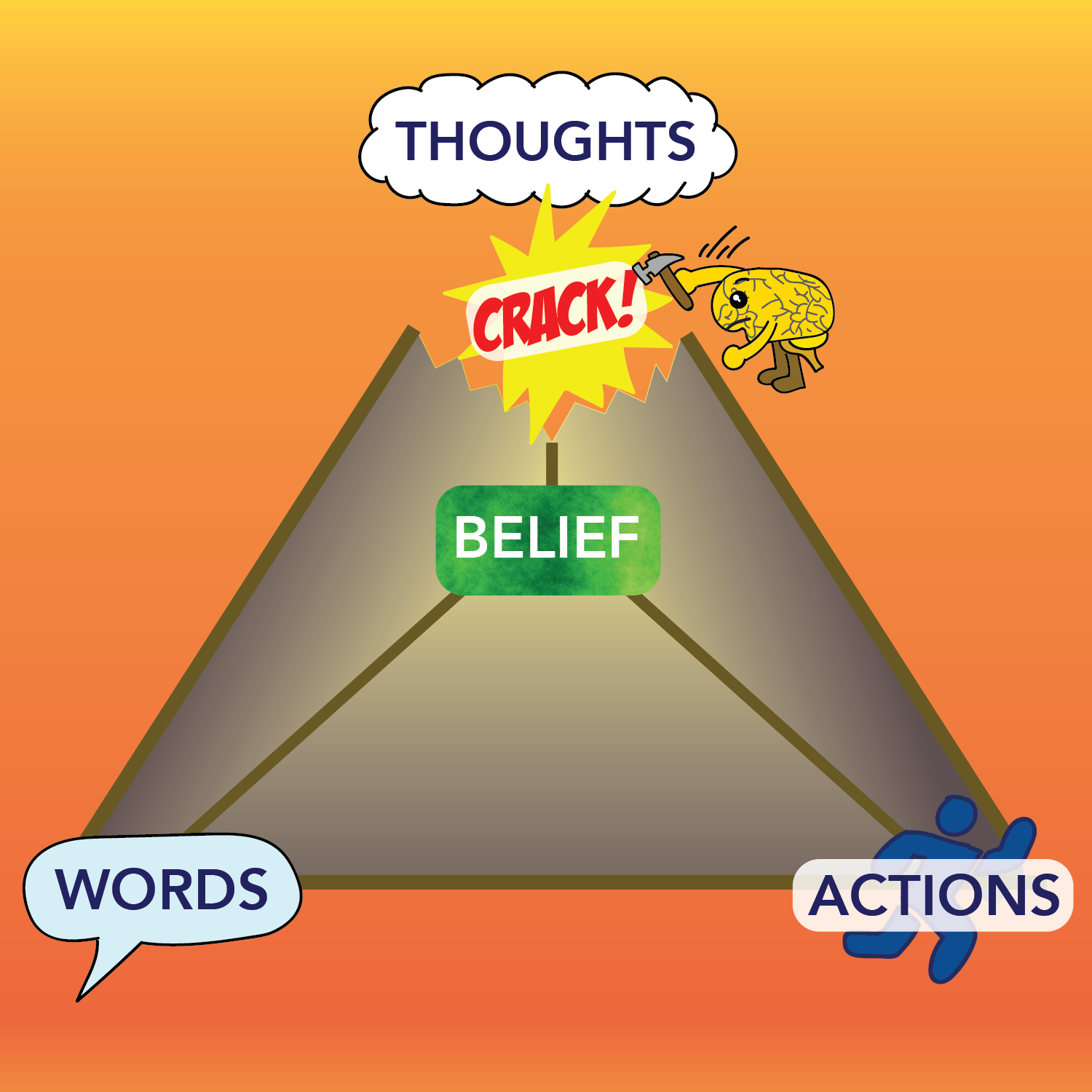

However, if I find that any one of the points aren’t satisfied, the triangle must break. Introspection is the key ingredient to determine if a belief holds, and it must be used frequently.4

We’ve already explored the words and actions areas, but I want to linger on the endpoint of thought for a moment. I find that there are so many parts of our lives where we believe things just because we feel that we ought to believe in them. We go against our own rational judgments all the time, just because the invisible force of obligation lurks in the background.

Here’s a common example. If you hate your job, you may deceive yourself into thinking that the job is okay so that you stay. Of course, you don’t really believe that the job is good for your personal development, but it’s certainly useful to believe that belief so you could carry on. After all, isn’t this what you should believe? Your family and friends (and maybe even yourself) would think you’re crazy if you quit, given the stability the job provides.

So rather than immerse yourself in a side project or find a more stimulating job, you remain in stasis, growing older in mind and body but not in skills or experience. This is how “belief in belief” works: It breaks the connection between your true thoughts and your stated beliefs, which cripples your judgment in the long-run.

This disconnect between thought and belief is found everywhere. It’s found in the lawyer that wants to be an entrepreneur, but fears what people will think. It’s found in the scientist that comes across a great observation, but hides it because it contradicts what he’s been saying for years. It’s found in the priest that would rather be a Buddhist, but is afraid of losing everything if he reveals this.

Often times, the thing that gets in the way of thought and belief is our concern for reputation. Rather than being true to ourselves, we want to fit the image that others expect. This concern clouds our judgment, making us less honest with our real beliefs and muting the inner voice that knows us best. This results in a lot of fickle “I should”s instead of definitive “I am”s, and obscures our ability to be clear thinkers.

To remove this fog, it’s important to reflect on the finiteness of existence, and that your beliefs are the only things that will direct your words, actions, and thoughts for this one life you’ll live. They are the maps that will guide you through the rocky terrain, and only you can draw your own.

More often than not, you will draw them in a way that aligns with your view of reality. But sometimes, you might find yourself drawing it in a way that goes against what you know is right.

Introspection is about checking yourself in that moment, and revising that misguided route to direct it toward the truth. It’s about being committed to drawing your map to the best of your ability, and not in a way that is convenient and reliant upon the expectations of others.

Earnestly believing what you believe is not as easy as it sounds, but it’s the only way to live a life that is aligned with everything you say, do, and think. The more Belief Triangles you form with that type of judgment, the more beacons of light you have to guide you toward clarity and wisdom.

So I leave you with this question: Do you really believe what you believe? For a question so simple, the answer is not. It’s a lifelong inquiry into examining who you truly are, so ask this question deeply, and ask it often.

Doing so will reveal more about yourself than you thought you ever knew.

_______________

_______________

For more posts on introspection and self-reflection: